COVID-19 patients are classified as mild, moderate, severe, and critical ill.[2] Since the disease severity of COVID-19 is associated with increased mortality and morbidity, knowing risk factors related to the severity of COVID-19 in thalassemia is crucial for managing these patients with COVID-19 timely. Obesity, cardiovascular disease, hemoglobinopathies, cancer, and diabetes mellitus are risk factors for COVID-19 severity.[3-5] Furthermore, in one cohort study, a blood-group–specific analysis demonstrated a higher risk in blood group A than in other blood groups and a protective effect in blood group O compared with other blood groups.[6]

Thalassemias are among the most common hereditary autosomal recessive blood disorders that 7% of people are affected globally.[7] Two clinical and hematological conditions are recognized based on the severity of clinical phenotypes of disease, i.e., non-transfusion-dependent (NTDT) and transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT).[8]

The data on the severity of COVID-19 in thalassemia patients are limited. Our aim was to investigate the severity of COVID-19 among thalassemia patients living in Iran, a country with a high prevalence of thalassemias and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A multicenter, retrospective and cross-sectional study were conducted across all comprehensive thalassemia centers in Iran, from January to August 2020 [15,950 TDT regularly transfused, every 2–4 weeks and 2,400 NTDT patients, registered by the Iranian Ministry of Health (MOH)]. Only COVID-19 cases, confirmed by the RT-PCR method, were collected from patients with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The patient's clinical characteristics [type of thalassemia, age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), splenectomy status, associated complications, and disease outcome], laboratory findings [including hemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), serum ferritin (SF), vitamin D], and imaging data were collected by analyzing patients' electronic medical records.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, and consent was taken from the patients or their legal guardians.

The COVID-19 disease severity was classified according to the guidance issued by the National Health Commission of China.[9] Mild cases present with mild symptoms without radiographic features, patients with a moderate disease present with fever, respiratory symptoms, and radiographic features. Patients with severe disease meet one of three criteria: (a) dyspnea (respiratory rate greater than 30 times/min), (b) oxygen saturation less than 94% in ambient air, and (c) PaO2/FiO2 less than 300 mmHg. Critical patients showed one of the following criteria: (a) respiratory failure, (b) septic shock, and (c) multiple organ failure. All patients were classified into three groups as asymptomatic or mild, moderate, and severe or critically ill to evaluate the risk factors between them. All hospitalized patients received prophylactic anticoagulation (Enoxaparin, 1 mg/kg/day subcutaneous) and a low- dose of aspirin (80 mg/day) in presence of platelet count > 500,000 per µL. Patients also received Remdesivir/Favipiravir, by our protocol to treat severe/ill-affected cases by COVID-19.

Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS statistics 26. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the quantitative data. Descriptive data were presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), median, range, and percentages where appropriate. Qualitative and quantitative variables were compared by Chi-square test and ANOVA test among three groups of patients with different disease severity, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison of the non-normally distributed data among three groups of patients. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Forty-eight patients (34 TDT and 14 NTDT) affected by COVID-19 were investigated. The overall mean age ± SD was 35.1 ± 11 (range: 9-67) years; 25 patients (52.1%) were females. Their mean pre-transfusion hemoglobin level was 9.2 ± 1.2 g/dl, and their median SF level was 1,020 (range: 142-17,000) ng/ml.

Based on our classification, the number of affected patients in each group was as follows: asymptomatic or mild (n=15), moderate (n=25), and severe or critical (n=8).

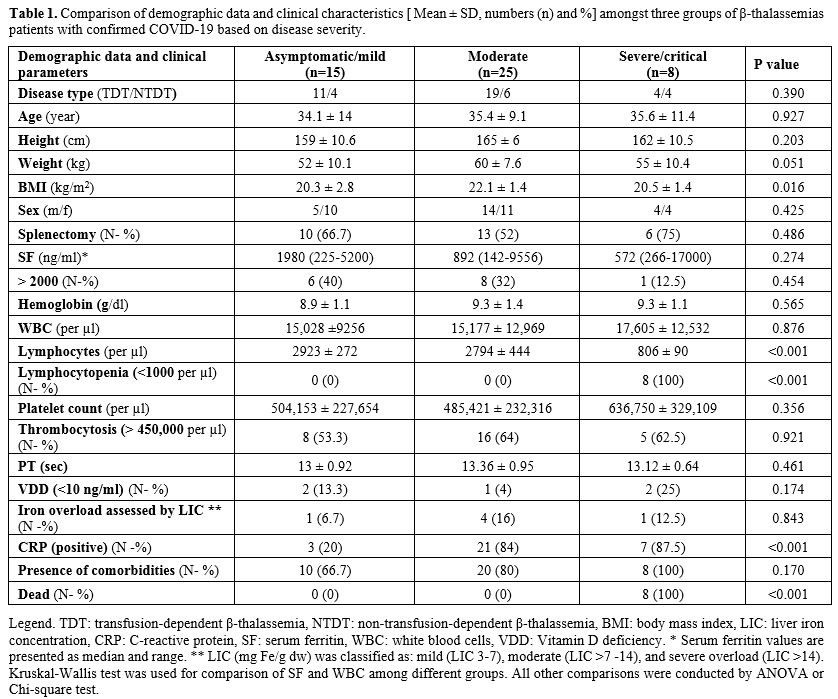

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients were presented in table 1.

|

Table

1. Comparison of demographic data and clinical characteristics [ Mean ±

SD, numbers (n) and %] amongst three groups of β-thalassemias patients

with confirmed COVID-19 based on disease severity. |

Lymphocytopenia (lymphocyte count < 1,000 per µl in adults and <3,000 per µl in children) was reported only in severely and critically ill patients. No thrombocytopenia cases were registered in our survey (platelet count range: 150,000-1,050,000 per µl). The frequency of thrombocytosis (platelet count > 450,000 per µl) in asymptomatic patients and those with mild COVID-19 was low and not statistically significant compared to moderate/severe groups (P=0.921). None of the patients included in the survey had a BMI equal or above 25 kg/m2. However, BMI was significantly different among the three groups of patients (P = 0.016).

Using the Bonferroni test, a significant difference we found between thalassemic patients with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 (BMI: 20.3 ± 2.8 kg/m2) vs. moderate group (BMI: 22.1 ± 1.4 kg/m2) (P=0.024).

All thalassemic patients with severe or critical COVID-19 died while no cases were registered in the other two groups of patients (P =<0.001).

The presence of comorbidities amongst the three groups of patients is reported in table 1. Overall, 38 patients (79.2%) had at least one comorbidity. Comorbidities were more frequent in patients with severe/critical (100%) and moderate (80%) COVID-19 compared to asymptomatic /mild (66.7%) COVID-19 patients, although the difference was not statistically significant (P =0.170).

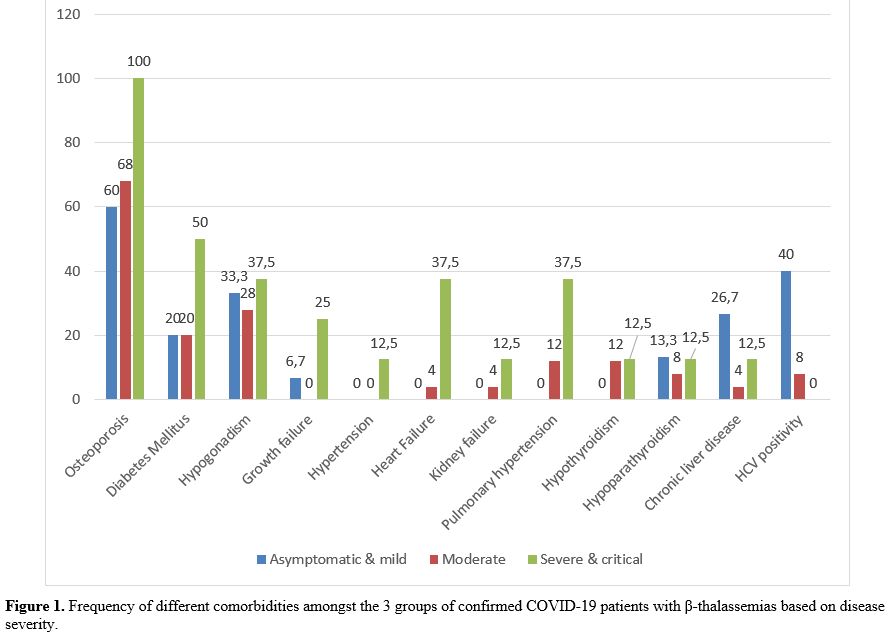

The distribution frequency of different comorbidities is illustrated in figure 1. The comparative analysis of the relationship of each comorbidity with COVID-19 severity showed a higher frequency in patients with severe or critical COVID-19 compared to moderate and asymptomatic or mild disease; however, the difference was only significant for heart failure and pulmonary hypertension, 37.5% versus 4% and 0% (P =0.012) for heart failure, and 37.5% versus 12% and 0%, for pulmonary hypertension (P =0.029). Moreover, a higher CRP frequency was found in severe/critical ill and moderate groups than asymptomatic or mild (P=<0.001).

|

Figure

1. Frequency of different comorbidities amongst the 3 groups of

confirmed COVID-19 patients with β-thalassemias based on disease

severity. |

Up to August 16, 2020, the prevalence of COVID-19 in patients with β-thalassemias was 26.2 per 10,000 and 40.6 per 10,000 in the general Iranian population (P=0.002). Unfortunately, it was impossible to compare the prevalence of COVID-19 in different specific age subgroups of thalassemia patients and the general population because access to these specific data for the Iranian population was unavailable.

At the same date, the total mortality rate was 16.7% in thalassemic patients with COVID-19 compared to the general Iranian population (5.7%; P= 0.001).

In conclusion, thalassemic patients with severe or critical COVID-19 had a higher frequency of comorbidities and a bad prognosis.

Our knowledge about COVID-19 is currently evolving, and knowing the risk factors for specific diseases that make these patients more vulnerable to severe or critical COVID-19 is very important. Potential general risk factors that have been identified to date include age, race/ethnicity, gender (males), and some associated medical conditions (such as cancer, chronic liver and kidney diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, immunocompromised state, severe obesity, cardiovascular diseases, sickle cell anemia, diabetes mellitus, and the use of certain medications). COVID-19 is primarily considered a respiratory illness, but the kidney may be one of the targets of SARS-CoV-2 infection since the virus enters cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptor, which is found in abundance in the kidney. Clinical presentation ranges from mild proteinuria to progressive acute kidney injury (AKI). The interaction between the blood coagulation system, adaptive immunity, and the complement pathway could influence AKI severity and outcome. The etiology is multifactorial, and management is supportive.[10-12]

Our study documented a significantly lower prevalence and a significantly higher mortality rate of COVID-19 in thalassemia patients in comparison with the general Iranian population. These data contrast with our previous report,[13] showing a similar prevalence in both groups of subjects, probably due to the different number of thalassemic patients included in the present study. However, it is essential to note that the reported number of confirmed cases and reported COVID-19 deaths in the general Iranian are likely to be underestimated.[14]

Children of all ages appeared susceptible to COVID-19 as we observe in the adult age groups, but it seems to be less severe than adult patients. However, children who have medical complexity, neurologic, genetic, metabolic conditions, or congenital heart disease might be at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 than other children.[15] In our study, all patients were older than 18 years old apart from one 9-year-old asymptomatic child diagnosed during a screening program.

It seems that thalassemia patients are more susceptible to COVID-19 severity due to the coexistence of multiple organ damage associated with iron overload. Although splenectomy is a risk factor for bacterial infection, it seems not to be a risk factor for COVID-19 disease severity.[4]

Our severe and critical ill group had more comorbidities than mild or moderate thalassemic groups. Heart failure and pulmonary hypertension (due to chronic anemia, hypoxemia, and thrombocytosis) resulted as significant risk factors for COVID-19 severity in our patients. We did not detect pulmonary embolism or thrombotic events in our patients during their hospitalization. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was non-significantly correlated to the severity of COVID-19, probably due to the limited number of affected patients. Nevertheless, we should consider that all known risk factors may potentially expose thalassemic patients to a higher risk rate of mortality, as we observed in patients' severe and critical ill groups. Therefore, adherence to iron chelation therapy to reduce SF and transferrin saturation index, as prognostic laboratory parameters, are crucial to reduce multiple organ damage, including heart failure, in TDT patients.

Moreover, close monitoring of pulmonary artery pressure measurement to detect pulmonary artery hypertension timely is essential to reduce the potential COVID-19 severity in patients with NTDT.[3,13] Furthermore, thrombo-inflammatory abnormalities are implicated in the progression of COVID-19, and thalassemia patients are already prone to thrombotic events, mostly in NTDT patients[8] requiring an appropriate treatment to prevent the risks of COVID-19. Finally, our data showed that the comorbidities associated with the severity of COVID-19 in thalassemia patients were not different from the general infected population.

The analysis of current evidence suggests that obesity is associated with a higher risk of developing moderate/severe symptoms and complications of COVID-19, independent from other illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease.[16] Nevertheless, an Italian report did not observe a significant severity risk of COVID‐19 in patients with thalassemia. However, the authors evaluated only 11 cases (10 with TDT and 1 with NTDT) of COVID‐19 in patients with thalassemias.[17]

The information on COVID-19 is evolving and knowing the risk factors associated with disease severity is very important to reduce morbidity and mortality in affected thalassemia patients by COVID-19. Because COVID-19 is a new disease, more work is needed to better understand the risk factors for severe illness or complications. Our present data confirm that the coexistent underlying disorders, including cardiovascular disease (heart failure and pulmonary artery hypertension), are associated with the disease severity of thalassemic patients affected by COVID-19. Therefore, close monitoring and timely management of comorbidities are crucial to reducing the mortality rate associated with the severity of COVID-19.