Fiorina Giona.

Hematology, Department of Translational and Precision Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy.

Correspondence to:

Fiorina Giona, MD. Hematology, Department of Translational and

Precision Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Via Benevento 6, 00161

Rome, Italy. Tel: +39-06-49974738. E-mail:

fiorina.giona@uniroma1.it

Published: November 1, 2021

Received: September 29, 2021

Accepted: October 23, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021069 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.069

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Mastocytosis

is a rare clonal disorder characterized by excessive proliferation and

accumulation of mast cells (MC) in various organs and tissues.

Cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), the most common form in children, is

defined when MC infiltration is limited to the skin. In adults, the

most common form is systemic mastocytosis (SM), characterized by MC

proliferation and accumulation in organs, such as bone marrow, lymph

nodes, liver, and spleen.[1] Genetic aberrations, mainly the KIT D816V

mutation, play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of mastocytosis,

enhancing MC survival and subsequent accumulation in organs and

tissues.[2,3] CM includes three forms: solitary mastocytoma,

maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MPCM), and diffuse cutaneous

mastocytosis (DCM). In most children with CM, skin lesions regress

spontaneously around puberty; unfortunately, it is not always a

self-limiting disease.[4] Even if SM occurs occasionally, all children

with mastocytosis require planned follow-up over time. Children with

mastocytosis often suffer from MC mediator-related symptoms, the most

common of which is itching, often triggered by rubbing the lesions.

Management of pediatric mastocytosis is mainly based on strict

avoidance of triggers. Treatment with H1 and H2 histamine receptor

blockers on demand and the availability of epinephrine auto-injectors

for the patients to use in case of severe anaphylactic reactions are

recommended.

|

Introduction

Mastocytosis

is a rare myeloproliferative disease characterized by an increase in

clonal morphologically and phenotypically abnormal mast cells (MC) that

accumulate in one or more organs and/or tissues. Most commonly, MCs

infiltrate the skin, the bone marrow (BM), liver, spleen, lymph nodes,

and gastrointestinal tract.[1-5] Disease manifestations can be due to

the release and activity of MC mediators and/or from the infiltration

of MC within affected organs.[5] Traditionally, the disease is divided

into cutaneous mastocytosis (CM) if MC infiltration is only localized

on the skin and systemic mastocytosis (SM) if MCs infiltrate various

organs, such as bone marrow, spleen, liver, and gastrointestinal tract,

and also the skin. According to the 2001 WHO classification, updated in

2008 and 2016, the diagnosis of SM can be established if at least 1

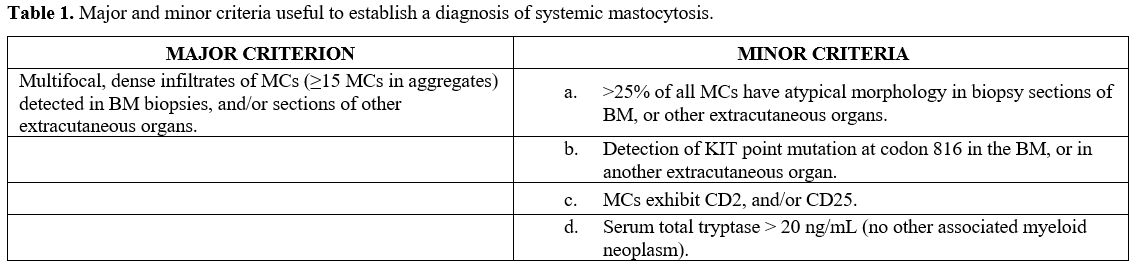

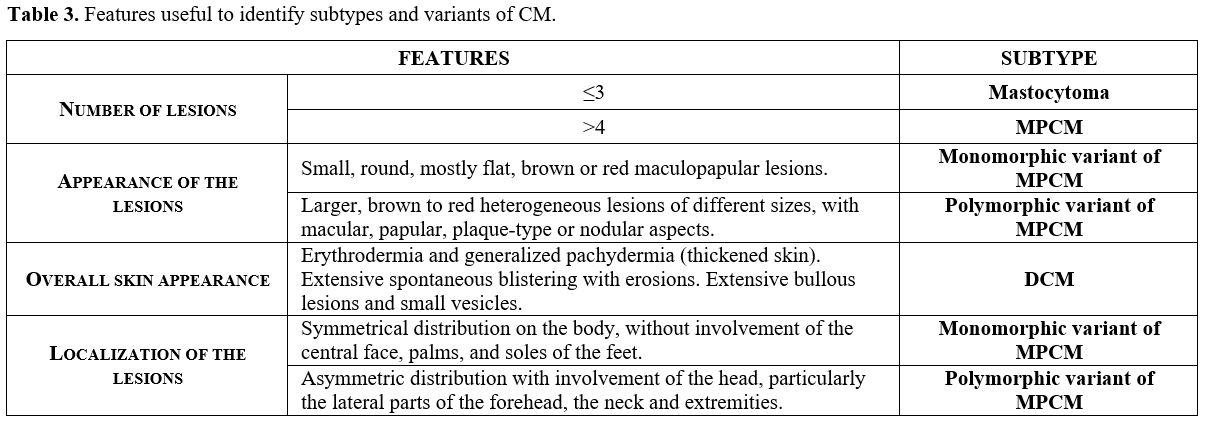

major and 1 minor, or 3 minor SM criteria, shown in table 1, are fulfilled.[6,7]

|

Table 1. Major and minor criteria useful to establish a diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis. |

CM is predominant in children, whereas the most common form of mastocytosis in adults is SM.

In

1869, the first pediatric case of mastocytosis localized in the skin

was described by Nettleship and Tay, but MC was first identified by

Elrich ten years later. The term urticaria pigmentosa was coined by Sangster in 1878 to describe skin lesions, while the term mastocytosis

was first used in 1936.[8] In 2007, an international Expert Working

Conference provided consensus statements on diagnostic criteria for

mastocytosis.[9] Three different forms of CM were identified: (1) solitary mastocytoma of the skin, (2) maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MPCM), and (3)

diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (DCM).[9] In addition, this Consensus

Group established diagnostic criteria to define CM: (a) the presence of

a typical skin lesion (major criterion), (b) increased numbers of MCs

in biopsy sections of the skin lesions (minor criterion), and (c) an activating KIT mutation at codon 816 in skin lesions (minor

criteria).[9,10,11] Recently, considering the different characteristics

of adulthood-onset and childhood-onset CM, an international task force

revised the classification and criteria for the diagnosis of cutaneous

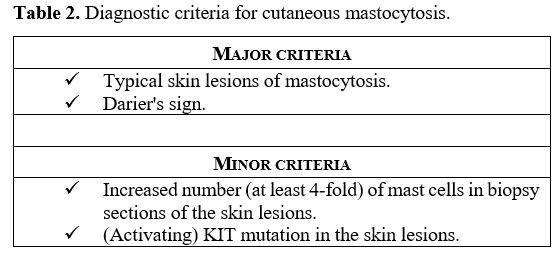

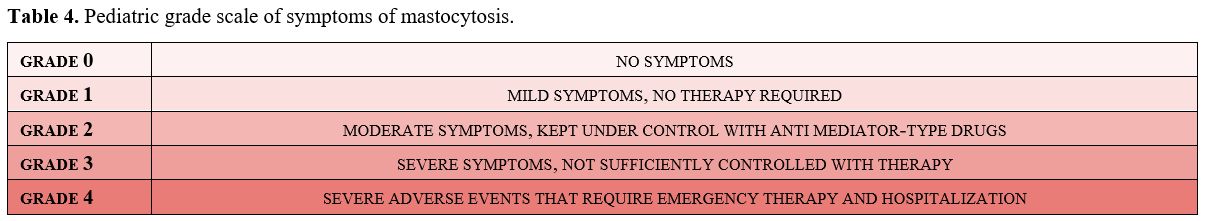

manifestations (Table 2).[10]

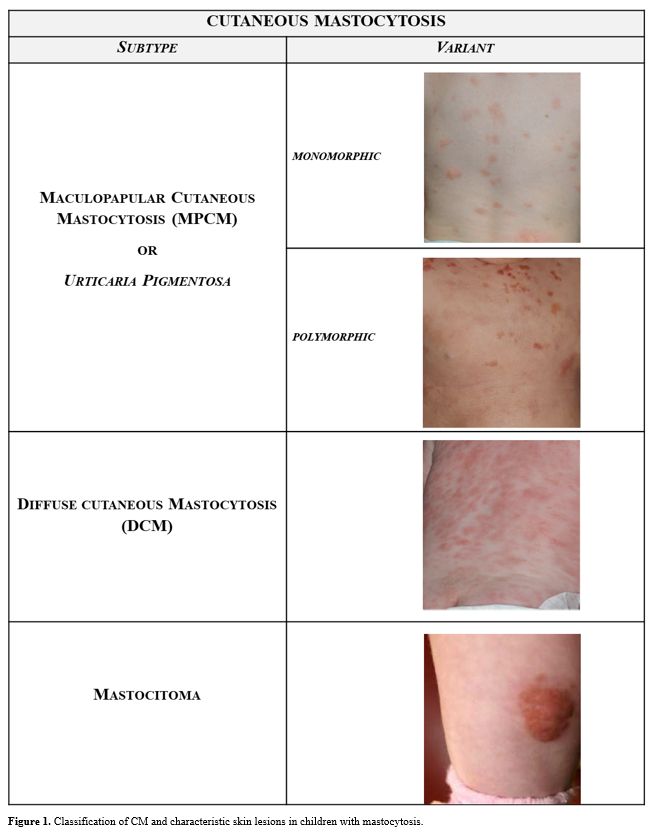

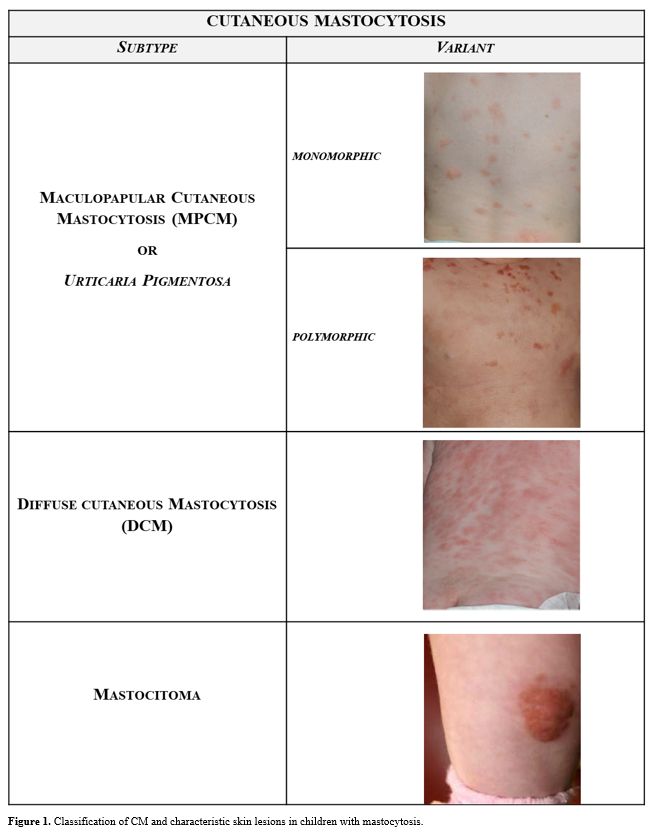

In particular, the MPCM subgroup was subdivided into 2 variants, namely

a monomorphic variant with small maculopapular lesions, which is

predominant in adult patients, and a polymorphic variant with larger

lesions of variable size and shape, which is typically seen in children

(Figure 1).

|

Table 2. Diagnostic criteria for cutaneous mastocytosis. |

|

Figure 1. Classification of CM and characteristic skin lesions in children with mastocytosis. |

Regarding the

criteria for diagnosis, Darier's sign was established as a major

criterion to define CM, as it is always positive in children with CM (Table 2).

Darier's sign is a skin change observed, within 15-30 minutes, upon

mild rubbing of the lesions. In general, the skin becomes red, swollen,

and itchy due to the release of MC mediators.

Epidemiology and Natural History

Mastocytosis

in the pediatric age is characterized by an almost exclusively

cutaneous involvement and is considered a clonal expansion of benign

nature, with spontaneous regression by puberty in more than 80% of

cases. Skin lesions are located predominantly on the trunk, less

frequently on the limbs, and rarely on the head.[4,10,12] Even if some

rare familial cases are described, pediatric mastocytosis is considered

a sporadic disease, not hereditary.[1] Late-onset of the disease in

pediatric age correlates with an increased risk of developing SM,

whereas cases of aggressive neonatal mastocytosis are extremely

rare.[11] The disease course may be characterized by the complete

absence of symptoms, or alternatively by the appearance of the MC

mediator-related symptoms such as itching, flushing, blisters,

wheezing, abdominal pain, cramping, reflux, ulcers, diarrhea,

hypotension, headache, and depression. The risk of anaphylaxis in

children with mastocytosis is higher compared to the general

population; however, allergic hypersensitivity to Hymenoptera venoms is

less than in adults with mastocytosis. Regarding the onset age of

pediatric mastocytosis, 55% of cases are diagnosed between birth to 2

years, typically in the first six months of life, 35% over 15 years of

age, and the remaining 10% of cases under 15 years. In childhood

mastocytosis, the male/female ratio is reported to be 1.4.[11] Clinical Presentiations

In

pediatric patients, the most common symptom is itching, caused by MC

degranulation and often triggered by rubbing the lesions.[13] Among the

various cutaneous lesions shown in Figure 1,

the MPCM is the most frequent form, detectable in about 70% of children

with mastocytosis, generally younger than two years. Skin

manifestations are mainly macules and papules, brownish or reddish;

plaques and nodules may coexist. Lesions of the MPCM form may have

either a monomorphic or, more frequently, a polymorphic appearance, the

latter having a better prognosis. MPCM-large lesions generally occur

under seven months of age, and MPCM-small lesions over two years of

age. In children with MPCM, the disappearance of the small lesions

takes longer (≥8 years) than the large ones.[13] In MPCM, Darier's sign

is characteristic.[14] Cutaneous mastocytoma, congenital or developed

within the third month of life, is diagnosed in about 15% of children

with mastocytosis. The term cutaneous mastocytoma can be used in the

presence of up to three lesions that are brown/yellow and are usually

localized on the trunk and limbs. If lesions are more than three, a

diagnosis of MPCM is made. Mastocytoma can increase in size and change

in morphology, but it does not generally increase and usually regress

by puberty.[10,15] Darier's sign is positive.

DCM is less

common, but it is the most severe clinical presentation of CM, with MC

infiltration of the entire skin (5-13%). It usually appears in very

young children. The skin is typically thickened and has a typical

orange-peel appearance. Vesicles of various sizes, even giant, are

frequent. DCM has an excellent chance of remission at five years,

although a high mortality rate (24%), mainly due to anaphylactic shock

and digestive bleeding, is reported. It is important to avoid Darier's

sign in patients with DMC, in order to minimise the potential massive

release of mediators from MCs.

In most cases, marked and

persistent dermographism occurs after minimal mechanical

irritation.[10,15] Elevated tryptase levels are found in a minority of

children, and systemic symptoms are not always indicative of SM.[16]

However, it is important to consider the possibility of evolution in

the systemic form. In a recent review of literature, it emerged that

approximately 1/100 children with CM would develop a systemic form.[15]

There are little data available regarding the role of the

environment or epigenetic factors in children's disease development or

progression. In a study including 32 patients, it was demonstrated that

some drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

beta-lactams, nifedipine, and levothyroxine, and or/and tobacco mothers

chronic exposure during pregnancy, negatively influenced spontaneous

disease remission in children. Surprisingly, it was found that children

who achieved complete regression of the disease had a chronic

dysreactive disease, usually asthma or eczema, before or after the

diagnosis of mastocytosis.[17]

Pathophysiology

The

pathogenesis of CM in children is still unclear. In the surface

membrane, MCs express a receptor for a stem cell factor, CD117, also

known as KIT. It is known that activating mutations of the gene

encoding the KIT receptor (c-KIT), observed among 90% of adults with

SM, play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of mastocytosis, enhancing

MCs survival with subsequent accumulation of MCs in various organs and

tissues.[6,18,19] Pediatric mastocytosis is considered a clonal

disorder associated with mutations of the proto-oncogene KIT in varying

ratios, from 0 to 83%.[17] The mutation of Kit codon 816 (D816V) in

exon 17, found in 80% of cases with adult-onset disease, was found in

only 42% of pediatric patients. Among children without any mutation of

codon 816 (D816V, D816Y, and D816I), other mutations involving exons 8,

9, 11, and 13 were found in 44% of them by sequencing the entire KIT

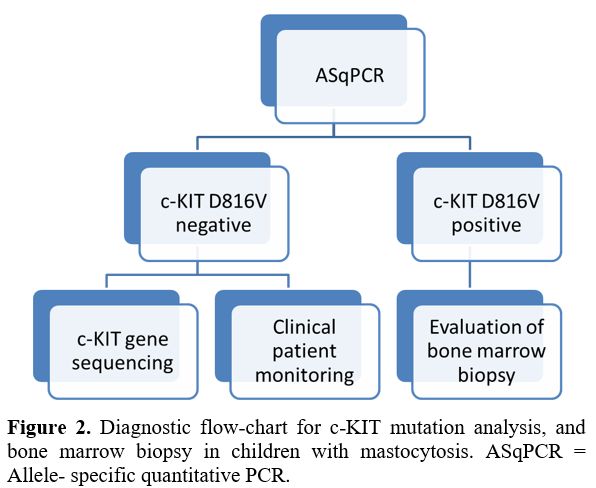

gene.[20] For this reason, in children with CM without KIT D816V

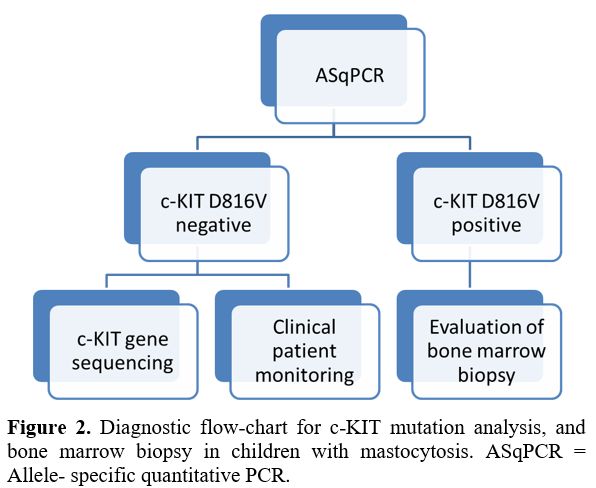

mutation, sequencing the entire c-KIT gene is recommended (Figure 2).

As a proportion of children do not show any c-KIT mutations, it is most

likely that other gene mutations could be responsible for the

pathogenesis of the disease.[18,20] The various c-KIT gene status, wild

type, mutations in exon 17, and other mutations found in children do

not correlate with clinical phenotypes, MPCM, DCM, and mastocytoma and

do not predict the outcome of the disease.[18,21-23] The presence of

c-KIT mutations of the MCs in the skin confirms the diagnosis of CM,

but this is not a diagnostic criterion for SM nor a predictor of the

evolution of the disease.[2,24,25] On the other hand, the presence of

KIT 816V mutation in the peripheral blood (PB) of children with CM

should suggest performing a bone marrow biopsy, which is useful for

identifying children at risk of developing SM.[18,26,27]

|

Figure

2. Diagnostic flow-chart for c-KIT mutation analysis, and bone marrow

biopsy in children with mastocytosis. ASqPCR = Allele- specific

quantitative PCR. |

Serum

tryptase levels (normal values <11.5 ng/ml), which include values of

protriptase, a molecule constitutively secreted by unstimulated MCs,

and mature tryptase, stored as secretory granules in cells, are

considered markers of MC activity.[28] In the pediatric age, increased

serum tryptase levels are more likely to indicate the presence of

active MC in the skin.[14] In a recent study, children with DCM showed

higher basal serum tryptase levels than those with mastocytoma and

MPCM.[29] It emerged from a previous study that children with MPCM with

smaller lesions had higher basal tryptase levels and presented a worse

outcome than those with larger ones.[30] High levels of basal serum

tryptase, combined with a skin lesion extension, in children with

mastocytosis were correlated with the possibility of developing very

serious symptoms due to the MC activation.[31] In the same study, the

tryptase cut-offs useful for better managing children with mastocytosis

were identified, as follows: a) 6.6 ng/ml: to start a daily

anti-mediator therapy; b) 15.5 ng/ml: to hospitalize the patient; c)

30.8 ng/ml: to admit the child to an intensive care unit. In case of

massive skin involvement and baseline serum tryptase values of 16

ng/ml, the initiation of intensive anti-mediator therapy is recommended

to reduce anaphylactic risk.[31] Tryptase levels were a good predictor

of pediatric anaphylactic events in a retrospective study including 102

children with CM.[32] In children with mastocytosis, over time, there

is a progressive decrease of tryptase levels, and it has been

speculated that this is probably due to pubertal hormones or

physiological reduced secretory activity by MCs during puberty.

Another

enzyme released from MCs is histamine (normal plasma levels in

children: 0.3–1.0 ng/mL). An increase in histamine levels has been

reported in children with DCM; however, an absolute correlation has not

been found between histamine levels and MC load in skin lesions.[33]

Serum histamine levels in DCM patients are higher during the first two

months of life but tend to decrease towards ages 9–12 months.[34] In

another study, children with mastocytosis and high histamine levels

showed more severe bone involvement and increased basal gastric acid

concentration.[34]

Some studies were carried out on the role of

some cytokines in pediatric mastocytosis. For example, increased levels

of Interleukin-31 (IL-31) were associated with the presence of

pruritus, and IL-6 was identified as a marker of mastocytosis

severity.[35]

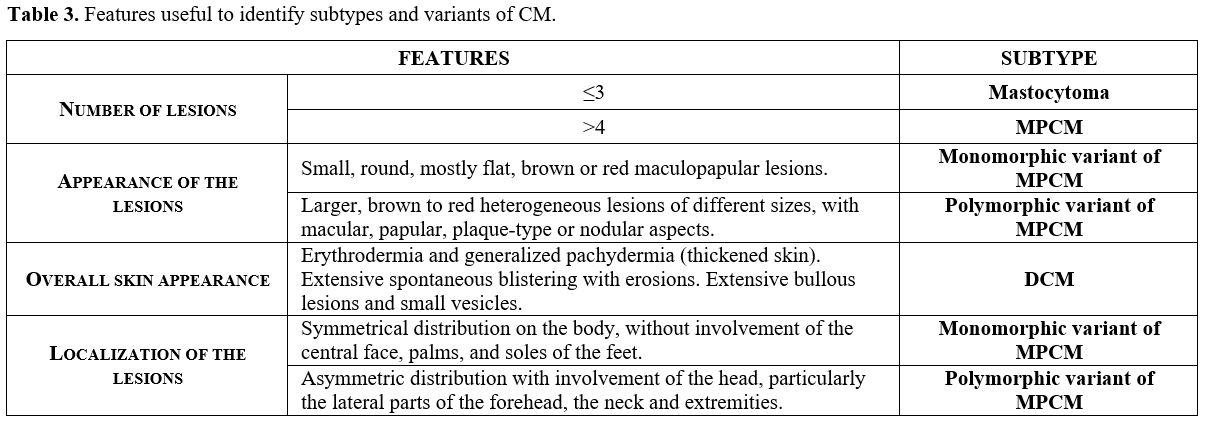

Diagnostic Assessments

Pediatric

mastocytosis is generally limited to the skin without signs or symptoms

of SM or other hematologic diseases. In clinical practice, the

diagnosis of CM in children is based on the morphology of the skin

lesions and the Darier's sign, considered as major criteria. An

important tool to define CM subtypes is to perform a detailed

evaluation of the cutaneous lesion features, including number and type,

mono or polymorphic appearance, color, size, localization, and overall

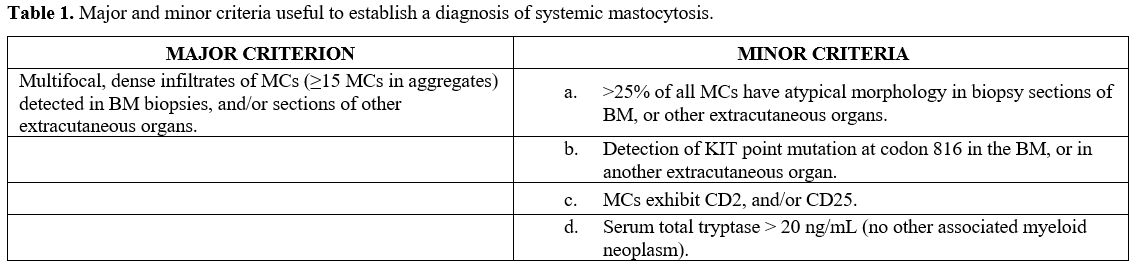

skin aspect (Table 3). Among

laboratory tests, the baseline serum tryptase levels are useful to

define the disease extension in children with CM, and they represent an

indicator risk of anaphylaxis and other severe allergic reactions in

this category of patients. It is important to consider that increased

serum tryptase may occur in other diseases, such as hereditary

alphatriptasemia, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, and nephropathies.

High tryptase levels without organomegaly and/or abnormal cell count

are not indicative of performing a BM evaluation.

|

Table 3. Features useful to identify subtypes and variants of CM. |

A

complete diagnostic assessment of children with CM, above all for those

with severe symptoms or extensive disease, includes a careful clinical

examination, complete blood cell counts, hepatic functions, and an

abdominal ultrasound to evaluate organomegaly. Allele-specific

quantitative PCR (ASqPCR) for KIT D816V mutation analysis in PB has

been recently added to a diagnostic algorithm for pediatric

mastocytosis if organomegaly, elevated tryptase, or severe MC

mediator-related symptoms are present.[18,37] KIT D816V mutation in PB

identifies the subgroup of children who need a more in-depth follow-up,

as they are at risk of SM.

Gastroscopy and colonoscopy with

biopsies are indicated when gastrointestinal symptoms are present. Bone

marrow biopsy is rarely needed in children with CM except when very

high serum tryptase levels (>100 ng/mL) are combined with cytopenia

undue to other causes but associated with organomegaly and/or

gastrointestinal symptoms are present.[18,37,38] Once the diagnosis is

established, patients could be followed according to the abnormalities

detected, how recently suggested by some researchers who proposed a

specific workup algorithm for children with CM.[18,26,37] If systemic

MC mediator symptoms or extensive disease (widespread MPCM or DCM) are

present, a close follow-up including abdominal ultrasound, tryptase

levels, and KITD816V detection in PB are useful. The evaluation of KIT

D816V mutation in PB during follow-up is of great importance to

identify the subgroup of children at risk of SM who need BM

investigation. Patients with isolated organomegaly, and/or high

tryptase levels, and negative KIT D816V mutation should also be

evaluated for other mutations in KIT (Figure 2).

Management and Treatment

Management

of children with CM is aimed to prevent or control symptoms related to

MC degranulation. The triggers vary in patients and can include

mechanical and physical stimuli, infections, dietary, and

drugs.[11,18,31] Avoiding extreme physical exercise, sudden temperature

changes, and skin lesions friction are simple measures to prevent

exacerbation.[24,25] Regarding dietary, various histamine-containing

foods (e.g., cured meats, smoked fish, aged cheeses, fermented foods,

eggplant, spinach) and histamine-releasing foods (e.g., citrus fruits,

strawberries, pineapple, tomatoes, nuts, shellfish, chocolate,

additives) are considered as triggers. In a recent study, the rate of

vaccine reactions in children with mastocytosis is slightly

higher than that reported in the general population (3–6%). Therefore,

in children with CM, the authors recommend single-vaccine regimens and

postvaccination observation for 1–2 hours, whereas vaccines should be

administered on the recommended schedule in those with other cutaneous

forms of mastocytosis.[39]

Since medications commonly used in

general anesthesia can degranulate MCs, choosing anesthetic agents with

a low capacity to elicit MC degranulation and a regularly scheduled

antihistamine treatment are usually recommended before and after

procedures.[40]

Treatment

In

pediatric mastocytosis, the treatment approach is influenced by the

presence and severity of symptoms caused by the release of MC mediators

and by the forms of skin lesions. Considering that MPCM and mastocytoma

often regress spontaneously, the use of topical and systemic

medications should be avoided in these categories of otherwise

asymptomatic patients.[18,41]

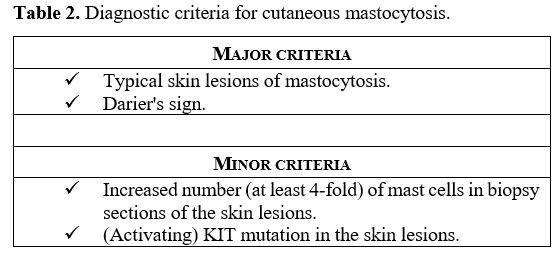

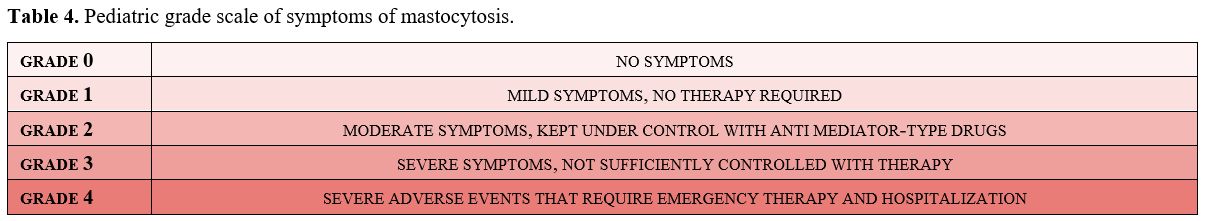

The severity of symptoms due to MC degranulation has been graded in order to permit the choice of appropriate treatment (Table 4).

The Standard Consensus Guidelines have established a 4-grade scale for

adults with mastocytosis, and it is also useful for therapeutic choice

and for monitoring the risk of possible systemic evolution in

children.[10,42]

|

Table 4. Pediatric grade scale of symptoms of mastocytosis. |

Systemic treatment of symptoms.

Treatment of symptoms caused by the release of MC mediators is the main

goal in managing patients with CM, including children. The severity,

type, and frequency of symptoms must be considered to choose the

therapeutic approach. H1-antihistamines, continuously given orally, are

recommended as first-line treatment and can be used on-demand in

children with less frequent symptoms. The second generation,

non-sedating H1-antihistamines, are preferred for patients with

frequent and/or problematic manifestations. In case of persistence of

the symptoms, it is advisable to add an H2 antihistamine or

anti-leukotriene (Montelukast).[43] H2-antagonists (e.g., ranitidine),

or proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole, pantoprazole,

lansoprazole), are indicated in case of gastrointestinal symptoms as

cramps and diarrhea.

The oral use of sodium cromoglycate to

control gastrointestinal manifestations is currently controversial

because comprehensive data on its mechanism of action is lacking.

The

use of systemic corticosteroids, limited by numerous side effects, is

indicated as a short course in children with extremely severe

mediator-related symptoms and extensive and persistent

blistering.[18,41,44,45]

Treatment of anaphylaxis.

The risk of anaphylaxis in children with mastocytosis is 5-10%.

Therefore, preventing or eliminating triggers for anaphylaxis is the

main goal. The exact indications of self-injectable epinephrine have

been the subject of debate; however, its prescription is recommended in

children with extensive skin mastocytosis, blistering, previous

episodes of anaphylaxis, and/or elevated serum tryptase levels. The

dose of epinephrine should be prescribed according to children's body

weight: 0.1 mg, 0.15 mg, 0.3 mg to a child weighing 7.5–15 kg, 15–30

kg, >35 kg, respectively. If necessary, epinephrine could also be

used for infants at a dose of 0.15 mg or 0.1 mg to a child weighing

<15 kg or <7.5 kg, respectively.[46-48]

Topical treatment.

Topical corticosteroids have always been by far the most widely used,

especially in patients with frequent blistering. However, their

long-term use is contraindicated due to the side effects on the skin

(atrophy) and adrenocortical suppression.[49] Instead of

corticosteroids, local application of pimecrolimus is recommended in

pediatric CM due to its excellent results and safety

profiles.[18,50,51] Pimecrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor with

significant anti-inflammatory activity by blocking T-cell activation,

inhibiting inflammatory cytokine synthesis, and immunomodulatory

effects with a low systemic immunosuppressive potential. Disodium

cromoglycate at a 1% to 4% concentration in an aqueous solution or

mixed with a water-based emollient cream may decrease

itching.[49,52,53] The use of phototherapy or photochemotherapy is not

recommended in children due to the potential carcinogenic effect. In

cases with diffuse localization, Narrow-band UVB rays (NB-UVB), UVA1,

UVA rays with psoralen (PUVA) therapy can be employed. The use of

lasers is very limited. Radical surgical excision is the extreme option

in solitary mastocytoma with high mediator release and a high risk of

anaphylaxis.[18,41]

Innovative therapies.

Several target drugs have been tested in pediatric mastocytosis.

Omalizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the

binding of IgE to the FceRI receptor on the surface of MCs, showed a

rapid and long-term efficacy to control severe MC-related symptoms in

an adolescent with frequent episodes of anaphylaxis.[54] Among kinase

inhibitors (KI) with activity against MC carrying D816V and other KIT

mutations, midostaurin, a multi-kinase inhibitor, is indicated to treat

aggressive SM in patients with D816V or wild type KIT. In childhood

mastocytosis, midostaurin was successfully used in an infant with

indolent SM associated with severe blistering who previously failed

conventional treatments.[55]

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI),

imatinib and masatinib, have different therapeutic indications.

However, the FDA approved imatinib's use in patients with SM and KIT

mutations outside of the exon 17, in the regulatory site (extracellular

and juxtamembrane portions of the gene), or with unknown mutations.[49]

Masatinib, a new highly selective TKI, targets wild-type KIT, LYN, and

FYN kinases that play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of

mastocytosis and could be effective in refractory cases with mutations

on the regulatory site of c-KIT. In addition, miltefosine is a

promising modulator of lipid rafts for topical use.[41]

Closing Remarks

Pediatric

forms of mastocytosis generally have a cutaneous presentation and

regress spontaneously with age. Acquired KIT receptor mutations, less

frequent in children than in adults, do not seem to be the only factor

responsible for triggering MC neoplastic transformation and do not

influence the development of the different clinical forms. New

molecular investigation techniques, including the Next Generation

Sequencing (NGS) method, may help identify other specific gene

aberrations, potentially useful to define alternative therapeutic

targets in forms of mastocytosis that require treatment.

Acknowledgments

I

thank Gianluca Signoretta, a graduating student who performed the

literature review for his dissertation; Martina Rousseau MD, who

reviewed the dissertation and Simona Bianchi MD, who reviewed the

references.

References

- Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, Longley BJ, Li CY,

Schwartz LB, Marone G, Nuñez R, Akin C, Sotlar K, Sperr WR, K Wolff, R

D Brunning, R M Parwaresch, K F Austen, K Lennert, D D Metcalfe, J W

Vardiman, J M Bennett. Diagnostic criteria and classification of

mastocytosis: A con-sensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001; 25:603-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00038-8

- Verzijl

A, Heide R, Oranje AP, van Schaik RHN. C-kit Asp-816-Val mutation

analysis in patients with mastocytosis. Dermatology. 2007; 214:15-20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000096907 PMid:17191042

- Arock

M, Sotlar K, Akin C, Broesby-Olsen S, Hoermann G, Escribano L,

Kristensen TK, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hermine O, Dubreuil P, Sperr WR,

Hartmann K, Gotlib J, Cross NC, Haferlach T, Garcia-Montero A, Orfao A,

Schwaab J, Triggiani M, Horny HP, Metcalfe DD, Reiter A, Valent P. KIT

mutation analysis in Mast Cell Neoplasms: Recommendations of European

Competence Net-work on Mastocytosis. Leukemia. 2015;29:1223-32. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2015.24 PMid:25650093 PMCid:PMC4522520

- Meni

C, Bruneau J, Gerogin-Lavialle S, Le Sachè de Peufeilhoux L, Damaj G,

Hadj-Rabis S, Fraitag S, Dubreuil P, Hermine O, Bodemer C. Pediatric

mastocytosis: A systematic review of 1747 cases. Dr J Dermatolog. 2015;

172:642-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13567 PMid:25662299

- Lange

M, Hartmann K, Carter MC, Siebenhaar F, Alvarez-Twose I, Torrado I,

Brockow K, Ren-ke J, Irga-Jaworska N, Plata-Nazar K, Ługowska-Umer H,

Czarny J, Belloni Fortina A, Caroppo F, Nowicki RJ, Nedoszytko B,

Niedoszytko M, Valent P.. Molecular background, clinical features and

management of pediatric mastocytosis: status 2021. Internat J Molec

Sciences. 2021; 22:2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052586 PMid:33806685 PMCid:PMC7961542

- Valent

P, Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification

and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood. 2017; 129:1420-1427. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-09-731893 PMid:28031180 PMCid:PMC5356454

- Hartmann

K, Valent P, Horny HP. Cutaneous mastocytosis. In World Health

Organization (WHO) Classification of Skin Tumours, 4th ed.; Elder,

D.E., Massi, D., Scolyer, R., Willemze, R., Eds.; International Agency

for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018; pp. 275-278.

- Mutter RD, Tannembaum M, Ultmann JE. Systemic mast cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 1963; 59:887-906. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-59-6-887 PMid:14082741

- Valent,

P.; Akin, C.; Escribano, L.; Födinger, M.; Hartmann, K.; Brockow, K.;

Castells, M.; Sperr, W.R.; Kluin-Nelemans, H.C.; Hamdy, N.A.; et al.

Standards and standardization in mastocy-tosis: Consensus statements on

diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur. J.

Clin. Investig. 2007, 37, 435-453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x PMid:17537151

- Hartmann

K, Escribano L, Grattan C, Brockow K, Carter MC, Alvarez-Twose I,

Matito A, Broesby-Olsen S, Siebenhaar F, Lange M, Niedoszytko M,

Castells M, Oude Elberink JNG, Bo-nadonna P, Zanotti R, Hornick JL,

Torrelo A, Grabbe J, Rabenhorst A, Nedoszytko B, Butterfield JH, Gotlib

J, Reiter A, Radia D, Hermine O, Sotlar K, George TI, Kristensen TK,

Kluin-Nelemans HC, Yavuz S, Hägglund H, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB,

Triggiani M, Maurer M, Nilsson G, Horny HP, Arock M, Orfao A, Metcalfe

DD, Akin C, Valent P. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with

mastocytosis: Consensus report of the European Competence Network on

Mastocytosis; the Ameri-can Academy of Allergy, Asthma &

Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical

Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 137:35-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034 PMid:26476479

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in Children. Curr Allergy Asthma Reports. 2017; 17:80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-017-0748-4 PMid:28988349

- Lange

M, Niedoszytko M, Renke J, Nedoszytko B. Clincal aspects of pediatric

mastocytosis: A review of 101 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.

2013; 27:97-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04365.x PMid:22126331

- Wiechers

T, Rabenhorst A, Schick T, Preussner M, Förster A, Valent P, Horny P,

Sotlar K, Hartmann K. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are

associated with favorable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis.

Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015; 136:1581-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.034 PMid:26152315

- Matito

A, Azaña JM, Torrelo A, Alvarez-Twose I. Cutaneous Mastocytosis in

Adults and Chil-dren: New Classification and Prognostic Factors.

Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2018; 38:351-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2018.04.001 PMid:30007456

- Lange

M, Niedoszytko M, Nedoszytko B, Łata J, Trzeciak M, Biernat W. Diffuse

cutaneous mastocytosis: Analysis of 10 cases and a brief review of the

literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Vene-reol. 2012; 26:1565-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04350.x PMid:22092511

- Sadaf H. Hussain: Pediatric mastocytosis, Curr Opin Pediatr 2020, 32:531-538 https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000922 PMid:32692050

- Ertugrul

A, Bostanci I, Kaymak AO, Gurkan A, Ozmen S. Pediatric cutaneous

mastocytosis and c-KIT mutation screening. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;

40:123-128. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2019.40.4201 PMid:30819282

- Lange

M, Hartmann K, Carter MC, Siebenhaar F, Alvarez-Twose I, Torrado I,

Brockow K, Renke J, Irga-Jaworska N, Plata-Nazar K, Ługowska-Umer H,

Czarny J, Belloni Fortina A, Caroppo F, Nowicki RJ, Nedoszytko B,

Niedoszytko M, Valent P.Molecular background, clinical features and

management of pediatric mastocytosis: status 2021, International

Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021; 22, 2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052586 PMid:33806685 PMCid:PMC7961542

- Pardoning,

A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk

stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2018; 94, 363-377. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25292 PMid:30328142

- Bodemer,

C.; Hermine, O.; Palmérini, F.; Yang, Y.; Grandpeix-Guyodo, C.;

Leventhal, P.S.; Hadj-Rabia, S.; Nasca, L.; Georgin- Lavialle, S.;

Cohen-Akenine, A.; et al. Pediatric mastocytosis is a clonal disease

associated with D816V and other activating c-KIT mutations. J.

Investig. Dermatol. 2010; 130, 804-815. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2009.281 PMid:19865100

- Méni,

C.; Georgin-Lavialle, S.; Le Saché de Peufeilhoux, L.; Jais, J.P.;

Hadj-Rabia, S.; Bruneau, J.; Fraitag, S.; Hanssens, K.; Dubreuil, P.;

Hermine, O.; et al. Paediatric mastocytosis: Long-term follow-up of 53

patients with whole sequencing of KIT. A prospective study. Br. J.

Dermatol. 2018, 179, 925-932. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16795 PMid:29787623

- Yang

Y, Létard S, Borge L, Chaix A, Hanssens K, Lopez S, Vita M, Finetti P,

Birnbaum D, Bertucci F, Sophie Gomez, Paulo de Sepulveda, Patrice

Dubreuil. Pediatric mastocytosis-associated KIT extracellular domain

mutations exhibit different functional and signaling properties

compared with KIT-phosphotransferase domain mutations. Blood. 2010;

116:1114-23. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-06-226027 PMid:20484085

- Li

Y, Li X, Liu X, Kang L, Liu X. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics

of Chinese neo-nates with cutaneous mastocytosis: A case report and

literature review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520952621. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520952621 PMid:32883129 PMCid:PMC7479863

- Azan

JM, Torrelo A, Matito A. Update on mastocytosis (part 2): Categories,

Prognosis, and Treatment. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2016; 107:15-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2015.11.002

- Castells

M, Butterfield J. Mast cell activation syndrome and mastocytosis:

Initial treatment op-tions and long-term management. J Allergy Clin

Immunol Pract. 2019; 7:1097-1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.002 PMid:30961835

- Carter

MC, Bai Y, Ruiz-Esteves KN, Scott LM, Cantave D, Bolan H, Eisch R, Sun

X, Hahn J, Maric I, Metcalfe DD. Detection of KIT D816V in peripheral

blood of children with manifestations of cutaneous mastocytosis

suggests systemic disease. Br J Haematol. 2018; 183:775-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15624 PMid:30488427

- Czarny

J, Zuk M, Zawrocki A, Plata-Nazar K, Biernat W, Niedoszytko M,

Ługowska-Umer H, Nedoszytko B, Wasag B, Nowicki RJ, Lange M. New

Approach to Paediatric Mastocytosis: Impli-cations of KIT D816V

Mutation Detection in Peripheral Blood. Acta Dermato-Venereol.

2020;100:adv00149. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3504 PMid:32399575

- Álvarez-Twose,

I.; Jara-Acevedo, M.; Morgado, J.M.; García-Montero, A.; Sánchez-Muñoz,

L.; Teodósio, C.; Matito, A.; Mayado, A.; Caldas, C.; Mollejo, M.; et

al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, and molecular characteristics of

well-differentiated systemic mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. mmunol.

2016, 137, 168-178.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.008 PMid:26100086

- Seth

N, Tuano KT, Buheis M, Chan A, Chinen J. Serum tryptase levels in

pediatric mastocytosis and association with systemic symptoms. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020; 125:219-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2020.04.021 PMid:32371241

- Barnes

M, Van L, De Long L, Lawley LP. Severity of cutaneous findings predict

the presence of systemic symptoms in pediatric maculopapular cutaneous

mastocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014; 31:271-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12291 PMid:24612340

- Alvarez-Twose,

I.; Vañó-Galván, S.; Sánchez-Muñoz, L.; Morgado, J.M.; Matito, A.;

Torrelo, A.; Jaén, P.; Schwartz, L.B.; Orfao, A.; Escribano, L.

Increased serum baseline tryptase levels and extensive skin involvement

are predictors for the severity of mast cell activation episodes in

children with mastocytosis. Allergy 2012, 67, 813-818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02812.x PMid:22458675 PMCid:PMC3349769

- Lange

M, Zawadzka A, Schrörs S, Słomka J, Ługowska-Umer H, Nedoszytko B,

Nowicki R. The role of serum tryptase in the diagnosis and monitoring

of pediatric mastocytosis: A single-center experience. AdvDermatol

Alergol. 2017; 34:306-12. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2017.69308 PMid:28951704 PMCid:PMC5560177

- Kettelhut, B.V.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mastocytosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 115S-118S. https://doi.org/10.1111/1523-1747.ep12468942 PMid:16799603

- Belhocine

W, Ibrahim Z, Grandné V, Buffat C, Robert P, Gras D, Cleach I, Bongrand

P, Carayon P, Vitte J. Total serum tryptase levels are higher in young

infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011; 22(6):600-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01166.x PMid:21736626

- Brockow,

K.; Akin, C.; Huber, M.; Metcalfe, D.D. IL-6 levels predict disease

variant and extent of organ involvement in patients with mastocytosis.

Clin. Immunol. 2005; 115, 216-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2005.01.011 PMid:15885646

- Hartmann

K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients

with mastocy-tosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network

on Mastocytosis; the American Acad-emy of Allergy, Asthma &

Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical

Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 137:35-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034 PMid:26476479

- Hussain, S.H. Pediatric mastocytosis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020; 32, 531-538. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000922 PMid:32692050

- Lange,

M.; Ługowska-Umer, H.; Niedoszytko, M.; Wasa˛g, B.; Limon, J.; Z˙

awrocki, A.; Ne-doszytko, B.; Sobjanek, M.; Plata-Nazar, K.; Nowicki,

R. Diagnosis of Mastocytosis in Children and Adults in Daily Clinical

Practice. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2016; 96,292-297. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2210 PMid:26270728

- Carter

MC, Metcalfe DD, Matito A, Escribano L, Butterfield JH, Schwartz LB,

Bonadonna P, Zanotti R, Triggiani M, Castells M, Brockow K. Adverse

reactions to drugs and biologics in patients with clonal mast cell

disorders: a group report of the Mast Cells Disorder Committee,

American Academy of Allergy and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2019; 143:880-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.063 PMid:30528617

- Hermans

MAW, Arends NJT, Gerth van Wijk R, van Hagen PM, Kluin-Nelemans HC,

Oude Elberink HNG, Pasmans SGMA, van Daele PLA. Management around

invasive procedures in mas-tocytosis: an update. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol. 2017; 119:304-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.022 PMid:28866309

- Czarny,

J.; Lange, M.; Ługowska-Umer, H.; Nowicki, R.J. Cutaneous mastocytosis

treatment: Strategies, limitations, and perspectives. Adv. Dermatol.

Alergol. 2018; 6, 541-545. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2018.77605 PMid:30618520 PMCid:PMC6320483

- Torrello, A.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Escribano, L. Childhood mastocytosis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012; 24, 480-486. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e328355b248 PMid:22790101

- Turner

PJ, Kemp AS, Rogers M, Mehr S. Refractory symptoms successfully treated

with leuko-triene inhibition in a child with systemic mastocytosis.

Pediatr Dermatol. 2012; 29:222-3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01576.x PMid:22044360

- Broesby

Broesby-Olsen, S.; Dybedal, I.; Gülen, T.; Kristensen, T.K.; Møller,

M.B.; Ackermann, L.; Sääf, M.; Karlsson, M.A.; Agertoft, L.; Brixen,

K.; et al. Multidisciplinary Management of Mas-tocytosis: Nordic Expert

Group Consensus. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2016; 96, 602-612. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2325 PMid:26694951

- Siebenhaar,

F.; Akin, C.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Maurer, M.; Broesby-Olsen, S.

Treatment strate-gies in mastocytosis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am.

2014, 34; 433-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2014.01.012 PMid:24745685

- González

de Olano, D.; de la Hoz Caballer, B.; Núñez López, R.; Sánchez Muñoz,

L.; Cuevas Agustín, M.; Diéguez, M.C.; Alvarez Twose, I.; Castells,

M.C.; Escribano Mora, L. Prevalence of allergy and anaphylactic

symptoms in 210 adult and pediatric patients with mastocytosis in

Spain: A study of the Spanish network on mastocytosis (REMA). Clin.

Exp. Allergy 2007; 37, 1547-1555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02804.x PMid:17883734

- Brockow,

K.; Jofer, C.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J. Anaphylaxis in patients with

mastocytosis: A study on history, clinical features and risk factors in

120 patients. Allergy 2008; 63, 226-232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01569.x PMid:18186813

- Matito,

A.; Carter, M. Cutaneous and systemic mastocytosis in children: A risk

factor for ana-phylaxis? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015; 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0525-1 PMid:26139333

- Klaiber,

N., Kumar, S., & Irani, A.-M. (2017). Mastocytosis in Children.

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 17(11). Doi

:10.1007/s11882-017-0748-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-017-0748-4 PMid:28988349

- Mashiah,

J.; Harel, A.; Bodemer, C.; Hadj-Rabia, S.; Goldberg, I.; Sprecher, E.;

Kutz, A. Topi-cal pimecrolimus for pediatric cutaneous mastocytosis.

Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2018; 43, 559-565. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13391 PMid:29460435

- Correia,

O.; Duarte, A.; Quirino, P.; Azevedo, R.; Delgado, L. Cutaneous

mastocytosis: Two pediatric cases treated with topical pimecrolimus.

Dermatol. Online J. 2010; 16, 8. https://doi.org/10.5070/D30FK211ZH PMid:20492825

- Edwards,

A.M.; Capková, S. Oral and topical sodium cromoglicate in the treatment

of diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis in an infant. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;

2011, bcr0220113910. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3910 PMid:22693187 PMCid:PMC3128352

- Vieira

Dos Santos, R.; Magerl, M.; Martus, P.; Zuberbier, T.; Church, M.K.;

Escribano, L.; Maurer, M. Topical sodium cromoglicate relieves

allergen- and histamine-induced dermal pruritus. Br. J. Dermatol.

2010;162, 674-676. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09516.x PMid:19785618

- Matito,

A.; Blázquez-Goñi, C; Morgado, JM; Alvarez-Twose, I; Mollejo, M;

Sánchez-Muñoz, L; Escribano, L. Short-term omalizumab treatment in an

adolescent with cutaneous masto-cytosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

2013; 111:425-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2013.08.014 PMid:24125156

- Liu

M, Kohn L, Roach G, et al. Treatment of systemic mastocytosis in an

infant with midostau-rin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;

7(2929-31):e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.032 PMid:31154031

[TOP]