Massimo Breccia, Corrado Girmenia, Roberto Latagliata, Giuseppina Loglisci, Michelina Santopietro, Vincenzo Federico, Luigi Petrucci, Alessandra Serrao, Adriano Salaroli and Giuliana Alimena

Published: May 16, 2011

Received: April 18, 2011

Accepted: May 9, 2011

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2011, 3: e2011021, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2011.021

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/8428

Abstract

Material and methods: From January 2001 to September 2006 we treated with imatinib 250 patients in first line (early CP) or after interferon failure (late CP), out of clinical trials and recorded all the bacterial and viral infections occurred.

Results: We recorded a similar incidence of bacterial and viral infections both in first line and late CP patients (respectively, 16% and 13%) during 3.5 years of follow-up. Analysis of presenting features predisposing to infections revealed differences only in late CP patients, with elevated percentage of high Sokal risk patients and a more longer median time from diagnosis to start of imatinib.

Conclusions: Opportunistic infections and reactivation of Herpes Zoster are observed during imatinib therapy at very low incidence.

Targeted

inhibition of BCR-ABL with imatinib mesylate has become the standard

therapy

for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) where it induces a

complete

cytogenetic response in more than 80% of newly diagnosed patients.[1] A

recent 8-year follow-up of IRIS study showed an overall survival (OS)

of 85%

and event-free survival (EFS) of 81%.[2] Several years

after the

introduction of imatinib in clinical practice no significant major

incidence of

infections was reported. However, different evidences that imatinib can

impair

several cellular functions involved in the immune response have been

observed,

in particular in cell-mediated immunity.[3-5] We refer

here on the

incidence of infectious episodes observed during imatinib treatment in

our

large series of early and late chronic phase CML patients.

Patients

and methods

All

consecutive patients with Ph+ CML in chronic phase out of clinical

trials who

started with imatinib therapy during the period from January

2001

to September 2006 were included in the study. The observation was

interrupted on December 2009 and patients lost to follow-up were

considered until last visit. Overall 250 patients were

considered: 150 patients had received prior therapy with Interferon

(IFN) for a median of 24 months (range 5-68) and were considered in

late chronic phase (CP) and, whereas 100 patients received imatinib

soon after diagnosis (early CP). No differences were observed regarding

Sokal risk: in early CP patients at baseline, 45% were low risk, 24%

intermediate and 3% were high risk. In late CP group, Sokal risk at the

time of imatinib start revealed 43% of patients as low risk, 50%

intermediate and 6.6% as high risk. Before starting imatinib, all

patients had baseline evaluation including physical examination,

complete blood cell count, renal and hepatic function tests, serum

protein electrophoresis, serum levels of IgG, IgA and IgM, bone marrow

(BM) aspirate with cytogenetic and molecular analyses, chest X ray and

cardiac evaluation. Physical examination and complete blood cell

count were performed weekly for the first month, then monthly. During

treatment, all side effects possibly related to drug and all infective

episodes, were evaluated and collected by medical staff. Only

clinically and microbiologically documented infections were included.

Febrile episodes of unknown origin in non-neutropenic patients (ANC

> 500/cmm), upper respiratory tract syndromes possibly related to a

viral infection and localized Herpes simplex were not considered in the

analysis.

Results

Overall, 36

clinically or microbiologically documented infections that required

antibacterial or antiviral therapy and discontinuation of imatinib were

recorded in 35 patients (incidence 14%). The characteristics of the

infective episodes are summarized in table

1.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients and of infective episodes.

In the series

of 100 CP patients who received imatinib as first line

therapy, with a median follow-up of 3.5 years, we recorded 17

infectious episodes in 16 patients (incidence 16%). They accounted for

0.02 infectious episodes per 1000 patient days. All the infective

episodes occurred at a median time of 13 weeks (range 9-26) from the

onset of imatinib treatment. No episode was associated to deep

neutropenia (absolute neutrophyl count < 500/cmm). Median

gammaglobulin dosage was 0.82 g/dl (range 0.7-2), with only 1 patient

presented with a slightly inferior dosage. Herpes zoster and pneumonia

represented the two more frequently observed infections occurring in 7%

and 4% of patients, respectively. In all patients who developed Herpes

zoster a reduction of lymphocyte count (median lymphocytes count 0.6 x

109/l, range 0.2-1.1, compared to 0.9 x 109/l of patients who did not

developed viral infections) was evidenced at the time of viral

infection (median time of development 11 weeks), in the absence of

induced leukopenia and serum Ig level (0.9 g/dl). One out of the 4

subjects who developed pneumonia presented two additional episodes of

fever with radiological evidence of pulmonary infiltrate diagnosed as

tuberculosis. This second infection occurred soon after underlying

hematologic disease progression to accelerated phase.

In the series of 150 patients treated with imatinib after

resistance/intolerance to interferon, observed for a median

follow-up of 4 years, we recorded 19 infective episodes (13%). They

accounted for 0.003 infectious episodes per 1000 patient days. Three

episodes of pneumonia and 2 urinary tract infections occurred during

neutropenia phase. Median gammaglobulin dosage was 0.93 g/dl (range

0.6-2.1), with only 2 patients presented with a slightly inferior

dosage. Fourteen late CP patients developed a Herpes zoster infection

during treatment with imatinib (median time of development 14 weeks):

these patients, as observed in the cohort of early CP patients, had a

significant reduction of lymphocyte count at the time of viral

infection (median lymphocytes count 0.8 x 109/l, range 0.2-1.2,

compared to 1.1 x 109/l of patients who did not developed viral

infections), in the absence of leukopenia and serum Ig level (0.8

g/dl). The infective episodes developed at a median time of 20 weeks

(range 10-28) from the onset of imatinib treatment and all occurred

during neutropenia induced by the drug, differently from what observed

in early CP patients. No infection-related death occurred and all

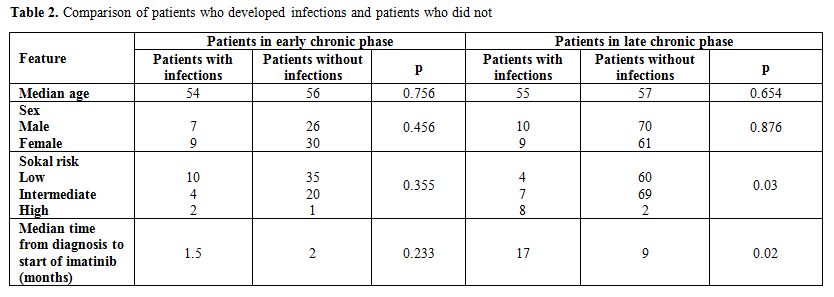

infections resolved in both groups of patients. Presenting features of

patients who developed infections and of those who did not were

compared (Table 2). In the

group of subjects in early CP there were no

statistically significant differences between patients who developed

infections and patients who did not. In patients in late CP a longer

interval of time between diagnosis and the start of imatinib (17 vs 9

months, p=0.02) and a prevalence of high Sokal risk (p=0.03) was

observed in patients who developed an infectious complication.

Table 2. Comparison of patients who developed infections and patients who did not

Discussion

Clinical and

laboratory findings seem to show that imatinib can impair several

cellular functions involved in the immune response. Two different

studies referred on a reduction of the immunoglobulin levels during

imatinib treatment for CML and for gastrointestinal stromal tumors

(GIST).[6,7] In the report of Steegmann et al6 only a

slight decrease of Ig levels in imatinib treated patients who had

became resistant or intolerant to interferon-alpha was documented: the

authors cannot rule out the possibility of an influence by the prior

therapy and suggested an impairment of B-lymphocytes or a mediated

effect through the inhibition of ABL kinase. Santachiara et al [7]

reported on 87 late CP patients treated with imatinib who presented a

reduction of Ig levels; these patients were treated with imatinib after

IFN for CML or were affected by GIST. The authors did exclude that this

effect had to be ascribed to interferon therapy and suggested that it

had to be considered the consequence of the imatinib treatment. CML

patients in CP are at low infectious risk compared to patients in more

advanced disease phases, however the epidemiological impact of

infectious complications in the imatinib era is unknown as infections

have not been enclosed in the safety analysis of large imatinib studies.[2,8]

Few reports on non-viral infections have been published during imatinib

therapy and anecdotic cases of pulmonary nocardiosis, pulmonary

tuberculosis, fungal pneumonia and listeria meningitis have been

reported.[9-12] In two of these observations, the

infections were concomitant to lymphopenia and monocytopenia. On the

contrary, viral infections, particularly those caused by herpes

viruses, seem to have a higher epidemiological impact.[13-15]

Mattiuzzi et al [13]

reported on a frequency of 2% of VZV reactivation in CML patients

treated with imatinib: baseline features of these subjects did not

differ significantly from those of patients who did not develop VZV

infection, except for the time from diagnosis to imatinib treatment and

the number of prior therapies. Few case reports reported on the

occurrence of other viral infections during imatinib therapy.[14-16]

In particular, the case of a fatal HHV8 infection in a CML patient in

complete molecular remission after imatinib was recently reported.[15]

In our experience, bacterial infection had a very low epidemiological

and clinical impact but VZV disease occurred more frequently than

previously reported.[13] Contrary to the study by

Mattiuzzi et al,[13]

all patients enclosed in our series were out of clinical trials,

probably with less favourable clinical characteristics. In fact, all

patients who developed the viral infection were aged over 50 years and

had comorbidities, such as diabetes and/or cardiac disease, conditions

which contraindicated the inclusion in clinical trials. We did not find

differences in the VZV incidence between early and late CP patients (7%

vs 9%). In any case, VZV infections accounted for only 0.04 infectious

episodes per 1000 patient days in the overall population, therefore

prophylaxis of VZV infection may not be recommended in this setting,

considering also the limited extent of the disease and the prompt

response to therapy. As to bacterial infections in late CP group, we

found that a longer interval of time between diagnosis and the start of

imatinib and a prevalence of high Sokal risk were prognostic adverse

events compared to early CP group: a possible explanation is that

previous treatment and high Sokal risk may influence the rate of

infections due to the possible scarce reserve of Ph negative cells.

Infectious episodes appeared concentrated in the first period of

treatment: this is in line with data from trials,[2]

in which toxicity was observed in the first year of treatment and new

events did not occur lately, again probably related to the initial

massive reduction of leukemic burden.

Conclusion

We observed

that opportunistic infections are an unusual complication also in a

“real life” population of CP - CML patients under imatinib therapy. No

life threatening and easy to treat Herpes zoster reactivations

represents the most frequently observed infectious complications.

Acknowledgements

No

grants were received from any of the authors for this paper.

Authorship: MB wrote and created the paper; RL, LC, GL, MS, AS, LP, VF

followed the patients; CG done microbacterial analysis; GA revised the

final version of the paper.

References

- Hochhaus A. First-Line management of CML: a

state of the art review. J Natl Compr Canc Netw Suppl 2008; 2: S1-S10

- Deininger MW, O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al. International randomized study of interferon vs STI571(IRIS) 8-year follow-up: sustained survival and low risk for progression or events in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with imatinib. Blood 2009; 114: 1126

- Cwynarski K, Laylor R, Macchiarulo E,

Goldman J, Lombardi G, Melo JV, Dazzi F. Imatinib inhibits the

activation and proliferation of normal T lymphocytes in vitro. Leukemia

2004; 18: 1332-1339 doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403401

PMid:15190258

- Sinai P, Berg RE, Haynie JM, Egorin MJ,

Ilaria RL Jr, Forman J. Imatinib mesylate inhibits antigen-specific

memory CD8 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol 2007; 178:

2028-2037PMid:17277106

- Chen CI, Maecker HT, Lee PP. Development

and dynamics of robust T-cell responses to CML under imatinib

treatment. Blood 2008; 111: 5342-5349 doi:10.1182/blood-2007-12-128397

PMid:18326818 PMCid:2396727

- Steegmann JL, Moreno G, AlŠez C, Osorio S,

Granda A, de la Camara R, Arranza E, Reino FG, Salvanes FR,

Fernandez-Ranada JM, Munoz C. Chronic myeloid leukemia patients

resistant to or intolerant of interferon alpha and subsequently treated

with imatinib show reduced immunoglobulin levels and

hypogammaglobulinemia. Haematologica 2003; 88: 762-768PMid:12857554

- Santachiara R, Maffei R, Martinelli S,

Arcari A, Piacentini F, Trabacchi E, Alfieri P, Ferrari A, Leonardi G,

Luppi G, Longo G, Vallisa D, Marasca R, Torelli G. Development of

hypogammaglobulinemia in patients treated with imatinib for chronic

myeloid leukemia or gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Haematologica 2008;

93: 1252-1255doi:10.3324/haematol.12642

PMid:18519520

- de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS,

Milojkovic D, Reid AG, Bua M, Szydlo R, Olavarria E, Kaeda J, Goldman

JM, Marin D. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid

leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat

analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 10;26:3358-63. Epub 2008 Jun 2.doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8154

PMid:18519952

- Daniels JM, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Janssen JJ,

Postmus PE, van Altena R. Tuberculosis complicating imatinib treatment

for chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 670-672 doi:10.1183/09031936.00025408

PMid:19251803

- Speletas M, Vyzantiadis TA, Kalala F,

Plastiras D, Kokoviadou K, Antoniadis A, Korantzis I. Pneumonia caused

by Candida krusei and Candida glabrata in a patient with chronic

myeloid leukemia receiving imatinib mesylate treatment. Med Mycol 2008;

46:259-263 doi:10.1080/13693780701558969

PMid:17885950

- Lin JT, Lee MY, Hsiao LT, Yang MH, Chao

TC, Chen PM, Chiou TJ. Pulmonary nocardiosis in a patient with CML

relapse undergoing imatinib therapy after bone marrow transplantation.

Ann Hematol 2004; 83: 444-446 doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0813-zPMid:14689232

- Ferrand H, Tamburini J, Mouly S, Bouscary

D, Bergmann JF. Listeria monocytogenes meningitis following imatinib

mesylate-induced monocytopenia in a patient with chronic myeloid

leukemia. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1684-1685 doi:10.1086/498031

PMid:16267747

- Mattiuzzi GN, Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Reuben

J, Rios MB, Shan J, Kontoyiannis D, Giles FJ, Raad I, Verstovsek S,

Ferrajoli A, Kantarjian HM. Development of Varicella-Zoster virus

infection in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with

imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9:976-980 PMid:12631595

- Ikeda K, Shiga Y, Takahashi A, Kai T,

Kimura H, Takeyama K, Noji H, Ogawa K, Nakamura A, Ohira H, Sato Y,

Maruyama Y. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation in a chronic myeloid

leukemia patient during imatinib mesylate treatment. Leuk Lymphoma

2006; 47: 155-157 doi:10.1080/14639230500236818

- Bekkenk MW, Vermeer MH, Meijer CJ, Jansen

PM, Middeldorp JM, Stevens SJ, Willemze R. EBV-positive cutaneous

B-cell lymphoproliferative disease after imatinib mesylate. Blood 2003;

102: 4243 doi:10.1182/blood-2003-07-2436

PMid:14623772

- Anthony N, Shanks J, Terebelo H.

Occurrences of opportunistic infections in chronic myelogenous leukemia

patients treated with imatinib mesylate. Leuk Res 2010; 34:1250-1251 doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2010.05.019

PMid:20646761