Review Articles

Antithrombotic

Prophylaxis in the Middle EastSamir Arnaout1, Hanady R. Samaha2, Julien Succar1, Imad Bou-Akl1, Khaled M. Musallam1, Ali T. Taher1

1American

University of Beirut Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon 2Saint

George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

Correspondence

to: Samir Arnaout, MD. Cardiology Division, Department of

Internal Medicine,

American University of Beirut Medical

Center, P.O. Box: 11-0236, Riad El-Solh 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon.

Phone:

+961-1-350000; Fax: +961-1-370814; Email: sarnaout@aub.edu.lb

Published: May 24, 2011

Received: January 26, 2011

Accepted: May 14, 2011

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2011, 3: e2011023, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2011.023

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/7901

This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Several

factors have been proposed to explain the persistence of a high

incidence of venous thromboembolism worldwide with its associated

morbidity and mortality. Underutilization of anticoagulants and failure

of adherence to thromboprophylaxis guidelines are emerging global

health concerns. We herein review this alarming observation with

special emphasis on the Middle East region. We also discuss strategies

that could help control this increasingly reported problem.

Introduction

It is well established that venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the most common preventable cause of death in the hospital setting, accounting for 5-10% of fatalities.[1-4] Furthermore, VTE is not restricted to the inpatient setting with several studies showing VTE frequently occurring post hospital discharge.[5-7] Despite the existence of guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in both medical and surgical patients,[8] medical centers worldwide continue to show elevated incidence rates of VTE.[1,9-12] This may be attributed to a significant gap between actual clinical practice and recommendations.[13-14] This review will highlight this alarming problem with emphasis on the Middle East region.

Results from The ENDORSE Study

The Epidemiologic International Day for the Evaluation of Patients at Risk for VTE in the Acute Hospital Care Setting (ENDORSE) study was a cross-sectional survey that assessed the adherence to the guidelines across 32 countries in 5 continents.[14] The study showed considerable variation among countries, with adherence to guidelines ranging from 0.2% to 92% for surgical patients and 3% to 70% for medical patients. The 2004 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines were used to stratify patients for VTE risk and need for anticoagulation.[14]

The compliance with the ACCP guidelines was only assessed in terms of the type of prophylaxis used, with dosing and duration not taken into account because of the differences in dosing recommendations across countries, and because of the cross-sectional nature of the study.[14] According to the study, the most common VTE risk factors are chronic pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure for medical patients, and obesity for surgical patients.[14]Complete and partial immobilization (immobilization with bathroom privileges), and admission to an intensive care unit were the most common risk factors for post-discharge VTE in both medical and surgical patients.[14]

Five Middle Eastern countries participated in the study: Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, collectively showing a guideline-adherence rate of 38%.[14] In comparison, other geographical regions in the study showed the following guideline-adherence rates: America (Brazil, Columbia, Mexico, USA, and Venezuela) 56%, Asia (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Thailand) 9%, Europe (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK) 56%, North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and Oceania (Australia) 46% and 57%, respectively. Globally, the study showed that 50% of all patients at-risk were receiving the ACCP recommended prophylaxis.[14]

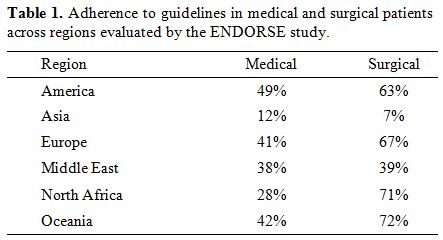

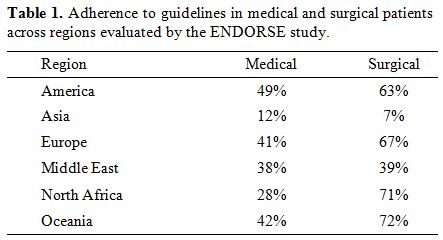

The ENDORSE study grouped patients according to whether they were medical or surgical cases. Medical patients were stratified based on the medical condition, and surgical patients based on the type of surgery they were undergoing.[14] It was shown that surgical patients received higher rates of recommended prophylaxis (59%) compared to medical patients (40%). The discrepancy in rates was significant in all regions except the Middle East, with medical and surgical guideline adherence rates being 38% and 39%, respectively (Table1).

Table 1. Adherence to guidelines in medical and surgical patients across regions evaluated by the ENDORSE study.

Finally, the ENDORSE study also reported the percentages of patients that received some form of prophylaxis irrespective of whether it followed the risk-stratification guideline of the ACCP. In the Middle East region, 45% of patients received some form of prophylaxis (41% medical, 48% surgical), with the other regions performing as follows: America 67% (63% medical, 71% surgical), Asia 11% (14% medical, 9% surgical), Europe 62% (49% medical, 71% surgical), North Africa 48% (31% medical, 72% surgical), and Oceania 66% (51% medical, 82% surgical).[14]

Results from the AVAIL ME Study

The Assessment for VTE Management in Hospitals in the Middle East (AVAIL ME) study was the first comprehensive evaluation of VTE prophylaxis in the Middle East region. It was conducted to properly evaluate the status of anticoagulation practices in the Middle East and to serve as a foundation for attempts at quality improvement.[15] The study included countries from the Middle East (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, and United Arab Emirates), and from Central Asia (Georgia, Iran, and Kazakhstan).[15] Previous studies on VTE prophylaxis in the Middle East were performed on diverse populations, across different timelines, employed varied methodologies, and were limited to predefined specialties (orthopedics, gynecology, etc), which made them unsuitable for adequate comparison.[15]

The study showed consistently lower rates of adherence to the guidelines in the Middle East region compared to global figures, thereby confirming the findings of the ENDORSE study.[15] Moreover, the study underlined the inappropriate utilization of prophylaxis in the Middle East in patients with contraindications, further emphasizing the divergence from the guidelines compared to the other regions.[16]

The study showed that 54.9% of patients received drug prophylaxis for VTE, but that only 36.9% received the 2004 ACCP recommended prophylaxis according to risk (the most up-to-date guidelines at the time of data collection).[15] Of the 2,266 patients in the study, 82.9% were eligible for prophylaxis according to the guidelines. 51.2% obtained some form of VTE prophylaxis, but only 37.8% according to the ACCP. 50.1% of eligible patients received drug prophylaxis (90.2% low molecular weight heparin, 10.7% unfractionated heparin, 1.5% vitamin K antagonists, and 0.1% fondaparinux), 16.4% received mechanical prophylaxis (graduated compression stockings in 97% of cases), 15.3% received both modalities, and the remaining received no prophylaxis.[15]

Stratification into risk groups revealed that guideline application was observed in 86.3%, 41.1%, 48.3%, and 24.5% in the low, moderate, high, and very high-risk groups respectively. Concurrently, some form of VTE prophylaxis was given to 17.9% of the low-risk patients, and in 41.7%, 60.6%, and 66.9% of the moderate, high, and very high-risk groups, respectively.[15]

The Kappa coefficient was calculated to evaluate concordance between eligibility for VTE prophylaxis and drug application, both according to guidelines, and was found to be equal to 0.16 (it ranges between 0 = no concordance, and 1 = perfect concordance) with a statistically significant P < 0.001. The study revealed that 45.1% of patients who should have received prophylaxis did not, and 26.9% of patients who were not eligible for prophylaxis did receive it. Separate Kappa values were also calculated after risk-stratification with values of 0.09 for moderate-risk, 0.20 for high-risk, and 0.09 for very high-risk patients (all statistically significant). Concordance for low-risk patients cannot be calculated because they should not receive prophylaxis.[15]

In the same study, it was observed that there were significant differences in adherence depending on the medical condition, with 40.2% of patients with ischemic stroke, 38.8% of cancer patients, and 35.7% of patients with heart failure (NYHA class III or IV) receiving prophylaxis according to the guidelines compared to only 26.7% of patients with hemorrhagic stroke and 26.8% of patients with renal failure.[15] This discrepancy in the use of prophylaxis among different medical conditions was also found in a previous study in Lebanon which showed higher prophylaxis rates in intensive care unit patients (62.5%) compared to patients admitted for malignancies (17.7%).[17]

In addition to the AVAIL ME study, several studies continue to show discordance in the Middle East between VTE prophylaxis and the guidelines.[18-19] These figures are more pronounced given the elevated proportion of the high-risk group in the region.[15] The observation that medical patients in the Middle East region receive less drug prevention than surgical patients is congruent with the results of other regional studies.[20-23] These results continue to emerge despite the finding that more than 70% of VTE events occur in medical patients compared to only 30% or less in surgical patients.[12,24-25]

Towards More than an Ounce of Prevention

Inappropriate thromboprophylaxis is a substantial problem that requires immediate attention. Efforts should be made to systematically assess patients at risk for VTE using practical models, urgently implement hospital-wide strategies, and provide appropriate prophylaxis to prevent this common and avoidable disease. This remains essential in developing countries with limited health care resources. Educational sessions targeting practicing physicians and staff and efforts towards changing guidelines to hospital policy should also ensue.

Several VTE risk assessment models (RAMs) and algorithms have been suggested.[20,26-31] However, most of these RAMs have not been prospectively validated, and the only two validated models present limitations that preclude widespread implementation.[30-31] The adoption of electronic tools was found to be effective in encouraging physicians to use prophylaxis at least amongst subgroups of patients at high-risk of thrombotic complications.[30-31] The electronic alerting systems, however, require sophisticated technology infrastructure and considerable financial resources, and are thus unlikely to find widespread acceptance across the many institutions that admit patients at risk of thrombosis. Self-explanatory, easy, suitable and effective RAMs may have the potential to help physicians manage their patients without the need for supplementary electronic tools, and may result in an increasing implementation of antithrombotic prophylaxis, in compliance with the recommendations of the main international guidelines and with the auspices of several world health organizations. A new simple points score system, the Padua Prediction Score,[32] was recently reported. The system was evaluated for its potential to detect hospitalized medical patients at high-risk for developing VTE, and its value was prospectively assessed in a broad spectrum of consecutive patients admitted to an Internal Medicine ward in a two-year period. All patients included in the study were prospectively followed-up for up to three months after admission in order to assess the incidence of symptomatic VTE. The simple 20-point RAM adopted clearly discriminated between hospitalized medical patients at high- and low-risk of VTE complications. The implementation of in-hospital thromboprophylaxis in patients classified as being at high-risk of thrombosis according to this RAM was highly effective, and was associated with an acceptably low-risk of bleeding. However, this benefit of this model needs to be prospectively evaluated.

Following pilot results of the AVAIL ME study, the alarming gap in adherence to practice guidelines led most involved centres, and many others, to start initiatives of careful planning to control the problem. Educational sessions targeting practicing physicians and staff and efforts towards changing guidelines to hospital policy ensued. These efforts are to be prospectively evaluated to determine their impact on the problem currently at hand.

Conclusion

The Middle East region has consistently lower rates of adherence to VTE prophylaxis guidelines, in both medical and surgical populations, compared to other regions. These shortcomings need to be addressed with outmost importance given the preventable nature of VTE, and the potential to substantially decrease associated morbidity and mortality in the region.

It is well established that venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the most common preventable cause of death in the hospital setting, accounting for 5-10% of fatalities.[1-4] Furthermore, VTE is not restricted to the inpatient setting with several studies showing VTE frequently occurring post hospital discharge.[5-7] Despite the existence of guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in both medical and surgical patients,[8] medical centers worldwide continue to show elevated incidence rates of VTE.[1,9-12] This may be attributed to a significant gap between actual clinical practice and recommendations.[13-14] This review will highlight this alarming problem with emphasis on the Middle East region.

Results from The ENDORSE Study

The Epidemiologic International Day for the Evaluation of Patients at Risk for VTE in the Acute Hospital Care Setting (ENDORSE) study was a cross-sectional survey that assessed the adherence to the guidelines across 32 countries in 5 continents.[14] The study showed considerable variation among countries, with adherence to guidelines ranging from 0.2% to 92% for surgical patients and 3% to 70% for medical patients. The 2004 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines were used to stratify patients for VTE risk and need for anticoagulation.[14]

The compliance with the ACCP guidelines was only assessed in terms of the type of prophylaxis used, with dosing and duration not taken into account because of the differences in dosing recommendations across countries, and because of the cross-sectional nature of the study.[14] According to the study, the most common VTE risk factors are chronic pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure for medical patients, and obesity for surgical patients.[14]Complete and partial immobilization (immobilization with bathroom privileges), and admission to an intensive care unit were the most common risk factors for post-discharge VTE in both medical and surgical patients.[14]

Five Middle Eastern countries participated in the study: Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, collectively showing a guideline-adherence rate of 38%.[14] In comparison, other geographical regions in the study showed the following guideline-adherence rates: America (Brazil, Columbia, Mexico, USA, and Venezuela) 56%, Asia (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Thailand) 9%, Europe (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK) 56%, North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and Oceania (Australia) 46% and 57%, respectively. Globally, the study showed that 50% of all patients at-risk were receiving the ACCP recommended prophylaxis.[14]

The ENDORSE study grouped patients according to whether they were medical or surgical cases. Medical patients were stratified based on the medical condition, and surgical patients based on the type of surgery they were undergoing.[14] It was shown that surgical patients received higher rates of recommended prophylaxis (59%) compared to medical patients (40%). The discrepancy in rates was significant in all regions except the Middle East, with medical and surgical guideline adherence rates being 38% and 39%, respectively (Table1).

Table 1. Adherence to guidelines in medical and surgical patients across regions evaluated by the ENDORSE study.

Finally, the ENDORSE study also reported the percentages of patients that received some form of prophylaxis irrespective of whether it followed the risk-stratification guideline of the ACCP. In the Middle East region, 45% of patients received some form of prophylaxis (41% medical, 48% surgical), with the other regions performing as follows: America 67% (63% medical, 71% surgical), Asia 11% (14% medical, 9% surgical), Europe 62% (49% medical, 71% surgical), North Africa 48% (31% medical, 72% surgical), and Oceania 66% (51% medical, 82% surgical).[14]

Results from the AVAIL ME Study

The Assessment for VTE Management in Hospitals in the Middle East (AVAIL ME) study was the first comprehensive evaluation of VTE prophylaxis in the Middle East region. It was conducted to properly evaluate the status of anticoagulation practices in the Middle East and to serve as a foundation for attempts at quality improvement.[15] The study included countries from the Middle East (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, and United Arab Emirates), and from Central Asia (Georgia, Iran, and Kazakhstan).[15] Previous studies on VTE prophylaxis in the Middle East were performed on diverse populations, across different timelines, employed varied methodologies, and were limited to predefined specialties (orthopedics, gynecology, etc), which made them unsuitable for adequate comparison.[15]

The study showed consistently lower rates of adherence to the guidelines in the Middle East region compared to global figures, thereby confirming the findings of the ENDORSE study.[15] Moreover, the study underlined the inappropriate utilization of prophylaxis in the Middle East in patients with contraindications, further emphasizing the divergence from the guidelines compared to the other regions.[16]

The study showed that 54.9% of patients received drug prophylaxis for VTE, but that only 36.9% received the 2004 ACCP recommended prophylaxis according to risk (the most up-to-date guidelines at the time of data collection).[15] Of the 2,266 patients in the study, 82.9% were eligible for prophylaxis according to the guidelines. 51.2% obtained some form of VTE prophylaxis, but only 37.8% according to the ACCP. 50.1% of eligible patients received drug prophylaxis (90.2% low molecular weight heparin, 10.7% unfractionated heparin, 1.5% vitamin K antagonists, and 0.1% fondaparinux), 16.4% received mechanical prophylaxis (graduated compression stockings in 97% of cases), 15.3% received both modalities, and the remaining received no prophylaxis.[15]

Stratification into risk groups revealed that guideline application was observed in 86.3%, 41.1%, 48.3%, and 24.5% in the low, moderate, high, and very high-risk groups respectively. Concurrently, some form of VTE prophylaxis was given to 17.9% of the low-risk patients, and in 41.7%, 60.6%, and 66.9% of the moderate, high, and very high-risk groups, respectively.[15]

The Kappa coefficient was calculated to evaluate concordance between eligibility for VTE prophylaxis and drug application, both according to guidelines, and was found to be equal to 0.16 (it ranges between 0 = no concordance, and 1 = perfect concordance) with a statistically significant P < 0.001. The study revealed that 45.1% of patients who should have received prophylaxis did not, and 26.9% of patients who were not eligible for prophylaxis did receive it. Separate Kappa values were also calculated after risk-stratification with values of 0.09 for moderate-risk, 0.20 for high-risk, and 0.09 for very high-risk patients (all statistically significant). Concordance for low-risk patients cannot be calculated because they should not receive prophylaxis.[15]

In the same study, it was observed that there were significant differences in adherence depending on the medical condition, with 40.2% of patients with ischemic stroke, 38.8% of cancer patients, and 35.7% of patients with heart failure (NYHA class III or IV) receiving prophylaxis according to the guidelines compared to only 26.7% of patients with hemorrhagic stroke and 26.8% of patients with renal failure.[15] This discrepancy in the use of prophylaxis among different medical conditions was also found in a previous study in Lebanon which showed higher prophylaxis rates in intensive care unit patients (62.5%) compared to patients admitted for malignancies (17.7%).[17]

In addition to the AVAIL ME study, several studies continue to show discordance in the Middle East between VTE prophylaxis and the guidelines.[18-19] These figures are more pronounced given the elevated proportion of the high-risk group in the region.[15] The observation that medical patients in the Middle East region receive less drug prevention than surgical patients is congruent with the results of other regional studies.[20-23] These results continue to emerge despite the finding that more than 70% of VTE events occur in medical patients compared to only 30% or less in surgical patients.[12,24-25]

Towards More than an Ounce of Prevention

Inappropriate thromboprophylaxis is a substantial problem that requires immediate attention. Efforts should be made to systematically assess patients at risk for VTE using practical models, urgently implement hospital-wide strategies, and provide appropriate prophylaxis to prevent this common and avoidable disease. This remains essential in developing countries with limited health care resources. Educational sessions targeting practicing physicians and staff and efforts towards changing guidelines to hospital policy should also ensue.

Several VTE risk assessment models (RAMs) and algorithms have been suggested.[20,26-31] However, most of these RAMs have not been prospectively validated, and the only two validated models present limitations that preclude widespread implementation.[30-31] The adoption of electronic tools was found to be effective in encouraging physicians to use prophylaxis at least amongst subgroups of patients at high-risk of thrombotic complications.[30-31] The electronic alerting systems, however, require sophisticated technology infrastructure and considerable financial resources, and are thus unlikely to find widespread acceptance across the many institutions that admit patients at risk of thrombosis. Self-explanatory, easy, suitable and effective RAMs may have the potential to help physicians manage their patients without the need for supplementary electronic tools, and may result in an increasing implementation of antithrombotic prophylaxis, in compliance with the recommendations of the main international guidelines and with the auspices of several world health organizations. A new simple points score system, the Padua Prediction Score,[32] was recently reported. The system was evaluated for its potential to detect hospitalized medical patients at high-risk for developing VTE, and its value was prospectively assessed in a broad spectrum of consecutive patients admitted to an Internal Medicine ward in a two-year period. All patients included in the study were prospectively followed-up for up to three months after admission in order to assess the incidence of symptomatic VTE. The simple 20-point RAM adopted clearly discriminated between hospitalized medical patients at high- and low-risk of VTE complications. The implementation of in-hospital thromboprophylaxis in patients classified as being at high-risk of thrombosis according to this RAM was highly effective, and was associated with an acceptably low-risk of bleeding. However, this benefit of this model needs to be prospectively evaluated.

Following pilot results of the AVAIL ME study, the alarming gap in adherence to practice guidelines led most involved centres, and many others, to start initiatives of careful planning to control the problem. Educational sessions targeting practicing physicians and staff and efforts towards changing guidelines to hospital policy ensued. These efforts are to be prospectively evaluated to determine their impact on the problem currently at hand.

Conclusion

The Middle East region has consistently lower rates of adherence to VTE prophylaxis guidelines, in both medical and surgical populations, compared to other regions. These shortcomings need to be addressed with outmost importance given the preventable nature of VTE, and the potential to substantially decrease associated morbidity and mortality in the region.

References

- Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Bergqvist D,

Lassen MR, Colwell CW, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the

Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy.

Chest 2004; 126:338S-400S. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.338S

PMid:15383478

- Lindblad B, Sternby NH, Bergqvist D.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism verified by necropsy over 30 years.

BMJ 1991; 302:709-711. doi:10.1136/bmj.302.6778.709

PMid:2021744 PMCid:1669118

- Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven

pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep

vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med 1989; 82:203-205. PMid:2716016

PMCid:1292084

- Alikhan R, Peters F, Wilmott R, Cohen AT.

Fatal pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients: a necropsy review. J

Clin Pathol 2004; 57:1254-1257. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.013581

PMid:15563663 PMCid:1770519

- White RH, Romano PS, Zhou H, Rodrigo J,

Bargar W. Incidence and time course of thromboembolic outcomes

following total hip or knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med 1998;

158:1525-1531.doi:10.1001/archinte.158.14.1525

PMid:9679793

- Dahl OE, Gudmundsen TE, Haukeland L. Late

occurring clinical deep vein thrombosis in joint-operated patients.

Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71:47-50. doi:10.1080/00016470052943883

PMid:10743992

- Arcelus JI, Monreal M, Caprini JA, Guisado

JG, Soto MJ, Nunez MJ, et al. Clinical presentation and time-course of

postoperative venous thromboembolism: Results from the RIETE Registry.

Thromb Haemost 2008; 99:546-551.PMid:18327403

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA, Jr., Levine MN,

Salzman EW, Wheeler HB. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest

1992; 102:391S-407S. doi:10.1378/chest.102.4_Supplement.391S

PMid:1395824

- Heit JA, Mohr DN, Silverstein MD, Petterson

TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ, 3rd. Predictors of recurrence after deep

vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based cohort

study. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:761-768.doi:10.1001/archinte.160.6.761

PMid:10737275

- Nordstrom M, Lindblad B, Bergqvist D,

Kjellstrom T. A prospective study of the incidence of deep-vein

thrombosis within a defined urban population. J Intern Med 1992;

232:155-160. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00565.x

- Oger E. Incidence of venous

thromboembolism: a community-based study in Western France. EPI-GETBP

Study Group. Groupe d'Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale.

Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:657-660. PMid:10823257

- Arcelus JI, Caprini JA, Monreal M, Suarez

C, Gonzalez-Fajardo J. The management and outcome of acute venous

thromboembolism: a prospective registry including 4011 patients. J Vasc

Surg 2003; 38:916-922. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(03)00789-4

- Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, Fitridge R,

Rowe S, Babidge W, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve

prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals. Ann Surg 2005;

241:397-415. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000154120.96169.99

PMid:15729062 PMCid:1356978

- Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF,

Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, et al. Venous thromboembolism

risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE

study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet 2008; 371:387-394.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60202-0

- Taher AT, Aoun J, Salameh P. The AVAIL ME

study: a multinational survey of VTE risk and prophylaxis. J Thromb

Thrombolysis 2011; 31:47-56 doi:10.1007/s11239-010-0492-2

PMid:20549305

- Deheinzelin D, Braga AL, Martins LC,

Martins MA, Hernandez A, Yoshida WB, et al. Incorrect use of

thromboprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in medical and surgical

patients: results of a multicentric, observational and cross-sectional

study in Brazil. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:1266-1270.doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01981.x

PMid:16706970

- Masroujeh R, Shamseddeen W, Isma'eel H,

Otrock ZK, Khalil IM, Taher A. Underutilization of venous

thromboemoblism prophylaxis in medical patients in a tertiary care

center. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2008; 26:138-141. doi:10.1007/s11239-007-0084-y

PMid:17701104

- Abba AA, Al Ghonaim MA, Rufai AM.

Physicians' practice for prevention of venous thromboembolism in

medical patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2004;

14:211-214.PMid:15228823

- Awidi A, Obeidat N, Magablah A, Bsoul N.

Risk stratification for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients

in a developing country: a prospective study. J Thromb Thrombolysis

2009; 28:309-313. doi:10.1007/s11239-008-0291-1PMid:19023522

- Goldhaber SZ, Tapson VF. A prospective

registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound-confirmed deep vein

thrombosis. Am J Cardiol 2004; 93:259-262. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.057

PMid:14715365

- Geerts W, Selby R. Prevention of venous

thromboembolism in the ICU. Chest 2003; 124:357S-363S. doi:10.1378/chest.124.6_suppl.357S

PMid:14668418

- Piazza G, Seddighzadeh A, Goldhaber SZ.

Double trouble for 2,609 hospitalized medical patients who developed

deep vein thrombosis: prophylaxis omitted more often and pulmonary

embolism more frequent. Chest 2007; 132:554-561.doi:10.1378/chest.07-0430

PMid:17573518

- Ageno W, Turpie AG. Deep venous thrombosis

in the medically ill. Curr Hematol Rep 2002; 1:73-78. PMid:12901127

- Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ,

Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, et al. A population-based

perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep

vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch

Intern Med 1991; 151:933-938.doi:10.1001/archinte.151.5.933

PMid:2025141

- Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB. Venous

thromboembolism. Risk factors and prophylaxis. Clin Chest Med 1995;

16:235-251.PMid:7656537

- Cohen AT, Alikhan R, Arcelus JI, Bergmann

JF, Haas S, Merli GJ, et al. Assessment of venous thromboembolism risk

and the benefits of thromboprophylaxis in medical patients. Thromb

Haemost 2005; 94:750-759. PMid:16270626

- Samama MM, Dahl OE, Mismetti P, Quinlan

DJ, Rosencher N, Cornelis M, et al. An electronic tool for venous

thromboembolism prevention in medical and surgical patients.

Haematologica 2006; 91:64-70. PMid:16434372

- Haas SK, Hach-Wunderle V, Mader FH, Ruster

K, Paar WD. An evaluation of venous thromboembolic risk in acutely ill

medical patients immobilized at home: the AT-HOME Study. Clin Appl

Thromb Hemost 2007; 13:7-13. doi:10.1177/1076029606296392

PMid:17164492

- Chopard P, Spirk D, Bounameaux H.

Identifying acutely ill medical patients requiring thromboprophylaxis.

J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:915-916. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01818.x

PMid:16634771

- Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, Cooper JM,

Paterno MD, Soukonnikov B, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous

thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 2005;

352:969-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041533

PMid:15758007

- Lecumberri R, Marques M, Diaz-Navarlaz MT,

Panizo E, Toledo J, Garcia-Mouriz A, et al. Maintained effectiveness of

an electronic alert system to prevent venous thromboembolism among

hospitalized patients. Thromb Haemost 2008; 100:699-704. PMid:18841295

- Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari

A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the

identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous

thromboembolism: The Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost 2010;

8:2450-7 doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x

PMid:20738765