Review Articles

Nilüfer Yeşilot Barlas, Gülşen

Akman-Demir and Sara Zarko Bahar

Published: October 24, 2011

Received: April 20, 2011

Accepted: October 13, 2011

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2011, 3(1): e2011044, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2011.044

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/8459

Abstract

Cerebral

venous and dural sinus thrombosis (CVT) is a rare condition

with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The epidemiology of the

disease

has evolved considerably during the recent decades with increasing oral

contraceptive use in young and

middle-aged women. CVT has various causes including genetic and

acquired

prothrombotic disorders and it usually has a favorable outcome with a

low rate

of thrombotic recurrence and mortality. Geographical and ethnic

variations

between populations may result in different distribution of CVT

etiologies

leading to different pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical

presentations.

In CVT series reported mostly from the

Cerebral

venous and dural sinus thrombosis (CVT) presents with a broad spectrum

of symptoms, and it is caused by a variety of etiologies.[1-2]

Nearly 85% of CVT cases have a prothrombotic risk factor or a direct

causative disorder. These include genetic and acquired prothrombotic

disorders, cancer, hematological diseases, pregnancy and puerperium,

systemic inflammatory diseases, neurosurgical procedures and some local

anatomical causes such as ear, head or neck infections. Around 40% of

CVT patients have more than one risk factor.[3] Among

the systemic inflammatory disorders, systemic lupus erythematotsus

(SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome, sarcoidosis and Behcet’s disease (BD)

can be listed.

CVT affects approximately 5 people per million annually.[4]

Although underlying factors may be common with other types of venous

thromboembolism, the unique way the central nervous system is affected

with CVT gives it an exceptional place under the concept of venous

thrombosis. Even though CVT can develop in the course of various

disorders, due to its clinical presentation most of the patients are

evaluated within stroke cohorts. CVT accounts for 0.5 to 1% of all

strokes.[2,4] In Istanbul Medical School Stroke

Registry CVT comprises 1% of all strokes.[5]

It is hard to estimate the number of CVT cases associated with various

etiological processes that are not included in stroke registries. The

largest information on CVT is provided by International Study on

Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT) comprised of 624

cases. In that prospective observational study, aimed to determine

prognosis of CVT, 624 symptomatic CVT cases from 21 countries were

registered over 3 years and ample information about all characteristics

of CVT patients were obtained as well. Fifty-seven percent of

these cases are from North-western Mediterranean countries (France,

Portugal, Spain and Italy). Overall 74.5% of patients were women and in

2/3rds of them CVT was associated with pregnancy, puerperium, oral

contraceptives (OC) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT); factors

associated with gender. The second most common etiological factor was

thrombophilia with a rate of 34%. However, these figures do not reflect

the true underlying factor incidence since in more than 40 % of the

cases there was more than one risk factor.

Information on epidemiology and risk factors for cerebral venous

thrombosis (CVT) in North-western Mediterranean countries are largely

available. On the contrary, information on CVT in the South-eastern

Mediterranean region is relatively sparse. The aim of this review is to

focus on CVT and inherited and acquired causes in countries of the

South-eastern Mediterranean region.

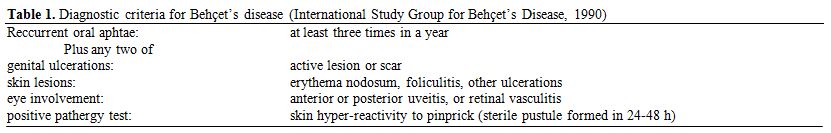

Behcet’s disease is one of the systemic inflammatory diseases with high

risk of venous thromboembolism and it is seen more commonly along the

Silk Route that extends from the Mediterranean region to Japan.[6]

In the South-eastern Mediterranean region etiology of CVT differs

compared to Western countries, due to the higher prevalence of Behcet’s

disease in the region. Behcet’s disease is a systemic inflammatory

disorder of unknown etiology, which presents with recurrent oral

aphtae, genital ulcerations, and uveitis. Diagnostic criteria for BD

are listed on Table 1.[7] Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is seen

about in 5-10% of cases with BD.[8-9]

Besides the more commonly encountered parenchymal neurological

involvement which occurs mainly as a brainstem meningoencephalitis,

intracranial hypertension due to CVT may be seen in about 15% of the

patients with neurological involvement. In our series this ratio was

17%, in another series from Tunisia it was 11%.[10-11]

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for Behçet’s disease (International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease, 1990)

Although population based studies are lacking from South-eastern

Mediterranean countries, a previous study comparing a series of CVT

patients with and without BD revealed that more than half of the

patients diagnosed with CVT have BD as the underlying factor. [12]

When the yearly rate of CVT patients are compared according to etiology

in this cohort 42% of the patients had BD as the causative factor

compared to all other etiologies complied as a separate group as the

underlying conditions for the remaining 58%.[12] One

point deserves further clarification because in this study, non-BD

group consisted largely of patients that were admitted to the hospital

with CVT; however, there may be another group of patients who present

with isolated ICH symptoms or only headache that were either not

diagnosed as CVT or were diagnosed but managed in the emergency room

due to relatively less serious clinical presentation and consequently

were not included in the database.

Behcet’s disease comprises a significant portion of CVT cases from many

Mediterranean countries, although the percentage varies according to

the country, and the center reporting the series. A series from France

analyzing isolated intracranial hypertension as the only sign of CVT

found that these patients consisted as high as 37% of all CVT patients

and 22% of them had BD as the underlying cause; however, this center is

one of the dedicated centers to Behcet’s disease in the country. In

this cohort other common etiological factors were coagulopathies,

unknown etiology, oral contraceptive use and other inflammatory

diseases.[13] On the other hand, data from Europe

depicts the rarity of BD as an etiological factor of CVT, there were

only 6 patients with BD among 624 patients registered in the ISCVT.[3] Interestingly, however, a small CVT series from

Lebanon did not have any patients with BD, among 16 cases.[14]

This might be reflecting a selection bias, as discussed below.

In another CVT series including only patients with cortical or deep

vein thrombosis, excluding patients with dural sinus thrombosis from

Turkey, similar frequencies of etiologies to those reported from the

West with few CVT patients with BD was reported.[15]

Albeit small in size, in this series the distribution of etiological

factors causing CVT among hormonal factors, malignancy, genetic

thrombophilia, infections, hematological disorders, vasculitis and

interventions was more or less similar to the largest cohort reported

from the rest of the world composed mostly of Nortwestern European

countries.[3,15] Most probably, the

inclusion of patients with only cortical or deep vein thrombosis was

the reason for this difference, supporting the clinical presentation

differences in CVT patients with and without BD emphasized in the

comparative study.[12] In a previous study of venous

thrombosis from Turkey, it was concluded that BD may be taking part

together with other etiologies in most of the cases;[16]

in that case when another etiology is found BD might have been

overlooked in some centers not so familiar with BD. On the other hand,

our center is a nationwide tertiary center with a specialized

multidisciplinary BD clinic and the frequency of CVT due to BD in our

center may be over-represented due to a selection bias. However, the

prevalence of BD was estimated as 42/10,000 (95% CI, 34-51/10,000) in

Istanbul, Turkey, supporting the notion that Turkey has the highest

prevalence rate of the disease in the world.[17]

Therefore it is not surprising to encounter BD as a frequent etiology

in CVT in the series reported from our center in Istanbul. Furthermore,

a recent review including CVT patients with BD mainly from countries in

the Mediterranean region showed that CVT incidence in BD was about 3

per 1000 person years.[18]

As mentioned above ¾ of the patients in ISCVT were women and the most

common risk factor was oral contraceptive use.[3]

However, in BD which is slightly more prevalent among males, serious

organ involvement is significantly more frequent in males and this

gender predisposition is also seen in cerebral venous thrombosis

patients with BD.[12] In the study where a direct

comparison was made in CVT patients with and without BD, CVT due to BD

was significantly more common among male patients. In the same study

the mean age was 26 in the non-BD group and 39 in the BD group,

resulting in a significant difference. However in the largest CVT

series published mean age was 37 for CVT patients, comparable to that

seen in BD patients with CVT.[3]

The rarity of acute presentation with neurological deficits and

seizures in patients with BD may preclude the inclusion of these

patients in other CVT series.[7] In CVT clinical

features differ according to the location and the extent of the

occlusion in the sinuses and veins and the course of the underlying

disease process. A slowly progressing dural sinus thrombosis that does

not affect the cortical venous circulation may present with isolated

headache and normal neurological examination findings. These patients

may be misdiagnosed as pseudotumor cerebri. However an acute clinical

presentation with focal neurological deficits and seizures can be

readily diagnosed as CVT with appropriate imaging techniques. CVT in BD

patients mostly presents with signs of isolated intracranial

hypertension and venous infarction rarely develops.[12]

As a consequence in CVT due to BD patients usually have an insidious

onset, they present usually with headache as the only symptom and the

neurological examination is normal or only papilledema or lateral gaze

paresis indicative of intracranial hypertension is found.

In the past, CVT used to be considered a condition with bad prognosis,

but currently CVT is considered to be a relatively more benign

condition with mortality rates below 10%.[19-23]

According to the limited follow-up data on CVT with and without BD

there were no significant differences between the two groups on

outcome.12 A greater tendency for recurrence was found in patients with

BD.[12] A cytopathological study on BD CVT cases is

not available however former autopsy findings on pulmonary arterial

thrombosis suggests an inflammatory process underlying the thrombosis.[24]

This finding may explain the chronic course of the thrombotic process

in CVT due to BD leading to the mentioned clinical differences.

The treatment of CVT mainly comprises of anticoagulation, with

subcutaneous fractionated heparin at the acute stage, and 6 months of

oral anticoagulation, afterwards.[25] However, since

the thrombosis of BD is considered an inflammatory process rather than

a procoagulant process,[26] treatment of these cases

may vary. Although treatment of CVT due to BD is still debated and

Class I evidence is lacking[27] our approach is to

use only steroids, instead of anticoagulants, as also suggested by

EULAR task force.[28] In such cases we usually give 5

consecutive days of IV methylprednisolone followed by a slow oral

taper.[29]

In recent years we also tend to add long-term azathioprine to prevent

recurrences or other vascular complications that could be seen in those

patients.[27] In intractable cases or repetitive CVTs

due to BD, anticoagulants may be added to steroids; but anticoagulants

should never be used alone.[29] It should be kept in

mind that pulmonary aneurysms should be ruled out before initiating any

anticoagulant treatment in patients with BD.

Due to the scarcity of data on CVT and inherited and acquired causes in

countries of the south-eastern Mediterranean region a comparison with

northwestern Mediterranean region is quite difficult to make. However,

one report emphasized the occurrence of CVT due to BD in Turkey which

deserves attention both in terms of the differences in demographic and

clinical features and possibly the treatment options. Therefore, in

patients with CVT from southeast Mediterranean region, BD should be

kept in mind especially if the patient is male, and if no other risk

factor can be identified. BD should always be questioned since

multi-etiology cases are not very rare. A multi-national and

multi-center prospective analysis of the CVT cases in south-east

Mediterranean region seems to be worthwhile in the near future.

References

- Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N

Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 28;352(17):1791-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra042354

PMid:15858188

- Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous

thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007 Feb;6(2):162-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70029-7

- Ferro JM, Canhao P, Stam J, Bousser MG,

Barinagarrementeria F. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus

thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and

Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004 Mar;35(3):664-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000117571.76197.26

PMid:14976332

- Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown

RD, Jr., Bushnell CD, Cucchiara B, Cushman M, et al. Diagnosis and

Management of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Statement for Healthcare

Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke

Association. Stroke. 2011 Feb 3.

- N. Yesilot BAK, R. Tuncay, O. Coban and S.

Z. Bahar. Gender differences in acute stroke: Istanbul Medical School

Stroke Registry. Neurology India. [Original Article].

2011;59(2):24-9.

- Siva A, Altintas A, Saip S. Behcet's

syndrome and the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004

Jun;17(3):347-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019052-200406000-00017

PMid:15167071

- Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet's disease.

International Study Group for Behcet's Disease. Lancet. 1990 May

5;335(8697):1078-80. PMid:1970380

- Serdaroglu P, Yazici H, Ozdemir C, Yurdakul

S, Bahar S, Aktin E. Neurologic involvement in Behcet's syndrome. A

prospective study. Arch Neurol. 1989 Mar;46(3):265-9.

PMid:2919979

- Siva A, Kantarci OH, Saip S, Altintas A,

Hamuryudan V, Islak C, et al. Behcet's disease: diagnostic and

prognostic aspects of neurological involvement. J Neurol. 2001

Feb;248(2):95-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004150170242

PMid:11284141

- Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasci B.

Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behcet's disease:

evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behcet Study Group. Brain. 1999

Nov;122 (Pt 11):2171-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/122.11.2171

PMid:10545401

- Houman MH, Neffati H, Braham A, Harzallah

O, Khanfir M, Miled M, et al. Behcet's disease in Tunisia. Demographic,

clinical and genetic aspects in 260 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007

Jul-Aug;25(4 Suppl 45):S58-64.

- Yesilot N, Bahar S, Yilmazer S, Mutlu M,

Kurtuncu M, Tuncay R, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in Behcet's

disease compared to those associated with other etiologies. J Neurol.

2009 Jul;256(7):1134-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-5088-4

PMid:19280104

- Biousse V, Ameri A, Bousser MG. Isolated

intracranial hypertension as the only sign of cerebral venous

thrombosis. Neurology. 1999 Oct 22;53(7):1537-42. PMid:10534264

- Otrock ZK, Taher AT, Shamseddeen WA,

Mahfouz RA. Thrombophilic risk factors among 16 Lebanese patients with

cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008

Aug;26(1):41-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11239-007-0093-x

PMid:17823778

- Sagduyu A, Sirin H, Mulayim S, Bademkiran

F, Yunten N, Kitis O, et al. Cerebral cortical and deep venous

thrombosis without sinus thrombosis: clinical MRI correlates. Acta

Neurol Scand. 2006 Oct;114(4):254-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00595.x

PMid:16942545

- Gul A, Aslantas AB, Tekinay T, Konice M,

Ozcelik T. Procoagulant mutations and venous thrombosis in Behcet's

disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999 Dec;38(12):1298-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/38.12.1298

PMid:10587567

- Azizlerli G, Kose AA, Sarica R, Gul A,

Tutkun IT, Kulac M, et al. Prevalence of Behcet's disease in Istanbul,

Turkey. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Oct;42(10):803-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01893.x

PMid:14521694

- Aguiar de Sousa D, Mestre T, Ferro JM.

Cerebral venous thrombosis in Behcet's disease: a systematic review. J

Neurol. 2011 Jan 6.

- Dentali F, Ageno W. Cerebral vein

thrombosis. Intern Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;5(1):27-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11739-009-0329-1

PMid:19949894

- Dentali F, Gianni M, Crowther MA, Ageno W.

Natural history of cerebral vein thrombosis: a systematic review.

Blood. 2006 Aug 15;108(4):1129-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-12-4795

PMid:16609071

- Breteau G, Mounier-Vehier F, Godefroy O,

Gauvrit JY, Mackowiak-Cordoliani MA, Girot M, et al. Cerebral venous

thrombosis 3-year clinical outcome in 55 consecutive patients. J

Neurol. 2003 Jan;250(1):29-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00415-003-0932-4

PMid:12527989

- Preter M, Tzourio C, Ameri A, Bousser MG.

Long-term prognosis in cerebral venous thrombosis. Follow-up of 77

patients. Stroke. 1996 Feb;27(2):243-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.27.2.243

PMid:8571417

- Deschiens MA, Conard J, Horellou MH, Ameri

A, Preter M, Chedru F, et al. Coagulation studies, factor V Leiden, and

anticardiolipin antibodies in 40 cases of cerebral venous thrombosis.

Stroke. 1996 Oct;27(10):1724-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.27.10.1724

PMid:8841318

- Hamuryudan V, Er T, Seyahi E, Akman C,

Tuzun H, Fresko I, et al. Pulmonary artery aneurysms in Behcet

syndrome. Am J Med. 2004 Dec 1;117(11):867-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.027

PMid:15589493

- Einhaupl K, Stam J, Bousser MG, De Bruijn

SF, Ferro JM, Martinelli I, et al. EFNS guideline on the treatment of

cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in adult patients. Eur J Neurol.

2010 Oct;17(10):1229-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03011.x

PMid:20402748

- Yazici H. Behcet's syndrome: an update.

Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003 Jun;5(3):195-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11926-003-0066-9

PMid:12744810

- Saadoun D, Wechsler B, Resche-Rigon M,

Trad S, Le Thi Huong D, Sbai A, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in

Behcet's disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Apr 15;61(4):518-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.24393

- Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B,

Chamberlain AM, Gul A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management

of Behcet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec;67(12):1656-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.080432

PMid:18245110

- Akman-Demir G SS, Siva A. Behcet’s

disease. Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 2011

Jun;13(3):290-310.