Outcome of Antifungal Combination Therapy for Invasive Mold Infections in Hematological Patients is Independent of the Chosen Combination

Rafael Rojas1, José R. Molina1, Isidro Jarque2, Carmen Montes3, Josefina Serrano1, Jaime Sanz2, Juan Besalduch4, Enric Carreras5, José F. Tomas6, Luis Madero7, Daniel Rubio8, Eulogio Conde3, Miguel A. Sanz2 and Antonio Torres1.

The Departments of Hematology and Stem Cell Transplantation Units of:

1 University Hospital Reina Sofia, Cordoba. Spain.

2 University Hospital La Fe, Valencia. Spain.

3 University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander. Spain.

4 University Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca. Spain.

5 University Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. Spain.

6 University Hospital MD Anderson, Madrid. Spain.

7 University Hospital Niño Jesús, Madrid. Spain.

8 University Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza. Spain.

1 University Hospital Reina Sofia, Cordoba. Spain.

2 University Hospital La Fe, Valencia. Spain.

3 University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander. Spain.

4 University Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca. Spain.

5 University Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. Spain.

6 University Hospital MD Anderson, Madrid. Spain.

7 University Hospital Niño Jesús, Madrid. Spain.

8 University Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza. Spain.

Correspondence

to:

Miguel A. Sanz, MD, PhD. Hematology Department, University Hospital La

Fe, Bulevar Sur s/n, 46026 Valencia. Spain. Tel/Fax number: 34-961 245

875. E-mail: msanz@uv.es

Published: February 10, 2012

Received: January 19, 2012

Accepted: February 8, 2012

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012, 4(1): e2012011, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2012.011

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/9832

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Invasive

mold infection (IMI) remains a major cause of mortality in high-risk

hematological patients. The aim of this multicenter retrospective,

observational study was to evaluate antifungal combination therapy

(ACT) for proven and probable IMI in hematological patients. We

analyzed 61 consecutive cases of proven (n=25) and probable (n=36) IMI

treated with ACT collected from eight Spanish hospitals from January

2005 to December 2009. Causal pathogens were: Aspergillus spp (n=49),

Zygomycetes (n=6), Fusarium spp (n=3), and Scedosporium spp (n=3).

Patients were classified in three groups according to the antifungal

combination employed: Group A, liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) plus

caspofungin (n=20); Group B, L-AmB plus a triazole (n=20), and Group C,

voriconazole plus a candin (n=21). ACT was well tolerated with minimal

adverse effects. Thirty-eight patients (62%) achieved a favorable

response (35 complete). End of treatment and 12-week survival rates

were 62% and 57% respectively, without statistical differences among

groups. Granulocyte recovery was significantly related to favorable

response and survival (p<0.001) in multivariate analysis. Our

results suggest that comparable outcomes can be achieved with ACT in

high risk hematological patients with proven or probable IMI, whatever

the combination of antifungal agents used.

Introduction.

Severe neutropenia and immunosuppression resulting from the use of high-dose chemotherapy in hematological diseases followed, in selected cases, by allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT), increase the susceptibility of patients to invasive fungal disease (IFD). The growing use of these aggressive therapies has led to a remarkable increase in the incidence of IFD.[1-3] Although fluconazole prophylaxis has reduced yeast infections in these vulnerable populations, invasive mold infections (IMI), particularly those caused by Aspergillus spp, have steadily increased to a 10-20% incidence rate. Furthermore, a high mortality rate for aspergillosis, the most common IMI, has been described, especially among allo-SCT recipients.[1-5] In addition, zygomycosis can reach attributable mortality rates of 91% in these patients.[6]

Many attempts have been made to decrease the incidence and mortality of IFD in patients with hematological malignancies. Strategies including empiric therapy, [7-9] pre-emptive treatment[10-13] and improved prophylactic regimens with new azoles have been proposed.[14-19] Monotherapy with new antifungal agents such as candins, triazoles and liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) has also been used as treatment for proven or probable IFD.[20-23] However, though improved survival rates have been documented with the use of these individual agents, overall response and treatment outcome remain suboptimal in cases of IMI with high mortality rates.

Recently, several retrospective or uncontrolled clinical reports[24-30] and, as far as we know, only one prospective randomized study[31] have addressed the potential benefit of using combinations of new antifungal agents in the treatment of IFD. This issue is conceptually promising, because an additive activity or even synergy of antifungal drugs might be expected.[32] Although these studies provide evidence supporting the use of this approach, the advantages of combined therapy have not yet been clearly demonstrated.[25-32] Therefore, it is still unclear if antifungal combined therapy (ACT) is superior to monotherapy in severely neutropenic and/or immunocompromised patients with life-threatening IFD.

In this retrospective, observational, multicenter study, we describe the results of ACT in 61 proven or probable cases of IMI occurring in high-risk hematological patients treated with intensive chemotherapy or allo-SCT.

Patients and Methods.

We have retrospectively analyzed all consecutive cases of high-risk hematological patients with proven or probable IMI treated with ACT in eight tertiary university hospitals in Spain over a 5-year period (January 2005 - December 2009). For inclusion in the analysis, patients must have received at least seven days of ACT. Antifungal agents used as primary prophylaxis, empiric treatments or in ACT depended on the specific policies of participating hospitals.

Definitions. Diagnosis of IMI was established according to the revised EORTC/MSG criteria.33 Responses to antifungal therapy were defined according to the MSG/EORTC consensus criteria34 as either favorable response (complete or partial) or failure (stable disease, progression or death from any cause).

Prophylaxis was defined as primary when patients did not have a previous history of IFD, while it was defined as secondary in patients with a previous IFD history but no signs or symptoms of fungal infection when the new hematological treatment was initiated.

ACT was started when the diagnosis of proven or probable IFD was made. The following doses were used in the treatment of adult patients: voriconazole, loading dose of 6 mg/kg/12 hours x 2 doses followed by 4 mg/kg/12 hours; posaconazole, 400 mg/12 hours; caspofungin, 70 mg on day 1 and 50 mg/day starting from day 2; anidulafungin, 200 mg on day 1 and 100 mg/day after and L-AmB, 3 mg/kg/day. The doses used in the treatment of children were: voriconazole, 7 mg/kg/12 hours; caspofungin, 70 mg/m2 (maximum 70 mg) on the first day and 50 mg/m2 (maximum 50 mg) each subsequent day and L-AmB, 3 mg/kg/day. All drugs were given intravenously but posaconazole was administered orally. Azole plasma levels were not monitored.

De novo ACT was defined as the combination of two antifungal drugs not used before for prophylaxis or empiric treatment. Sequential ACT occurred when an antifungal drug was added to another already being used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment.

Statistical Analysis. Data were collected in a SPSS database and all statistical results were performed using SPSS version 17. Either the chi-square or the Fisher’s exact test were used to compare data. Overall survival was analyzed using temporal series Kaplan-Meier analysis and comparisons between different treatments groups were performed using the log-rank test. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was used. A p value of less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results.

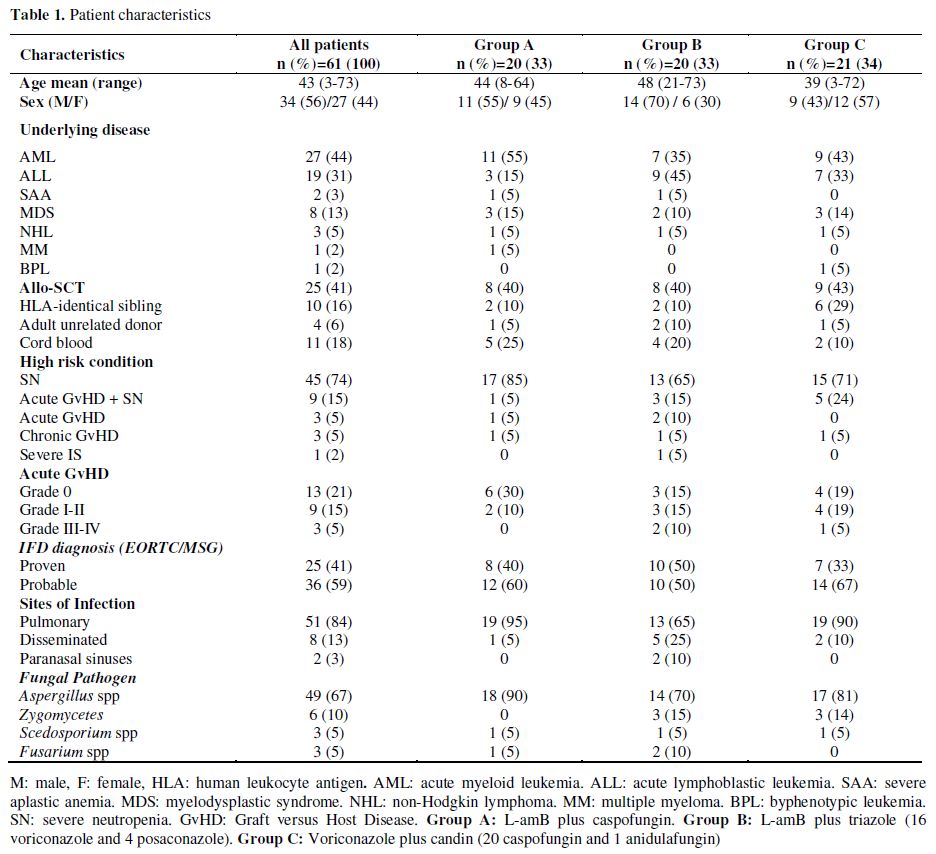

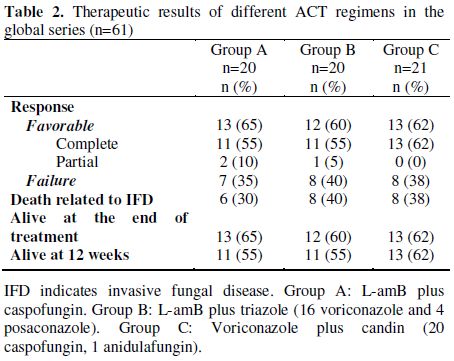

Patients. Sixty-one patients were included in the study. The mean age was 43 years (range, 3-73) with 7 patients younger than 18 years. Thirty-four patients had received intensive chemotherapy for induction (n=28) or consolidation (n=6). Twenty-five patients were recipients of allo-SCT and one patient received an autologous SCT. The main demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Fifty-four patients (89%) were severely neutropenic (absolute neutrophil count <500/L for at least 10 consecutive days) at the onset of IFD; of these, 9 had at the same time acute graft versus host disease (GvHD). Only 7 patients developed an IFD without severe neutropenia: 3 patients had acute GvHD, 3 patients chronic GvHD and 1 patient severe aplastic anemia under immunosuppressive treatment.

Prior antifungal prophylaxis was administered to 60 patients (23 voriconazole, 18 fluconazole, 18 itraconazole and 1 L-AmB). In 35 patients, prophylaxis was stopped when empirical antifungal treatment was initiated (9 patients were given voriconazole, 16 caspofungin and 10 L-AmB). The patient not receiving prophylaxis started empirical treatment with voriconazole. Only 3 patients with prior history of IFD (2 candidemias and 1 probable pulmonary aspergillosis) received secondary prophylaxis (1 fluconazole, 2 voriconazole).

De novo ACT was started in 26 patients. In 23 other patients, combined treatment was initiated by adding a new antifungal agent to the empirical treatment. In the remaining 12 patients, a second antifungal drug was added to the prophylaxis regimen.

The diagnosis of proven IFD was confirmed in 25 patients, while the remaining 36 patients met the criteria for probable IFD. The molds isolated in proven IFD cases were as follows: Aspergillus fumigatus (n=6), A. flavus (n=3), A. terreus (n=1), Aspergillus spp. (n=3), Mucor spp. (n=6), Fusarium oxysporum Table 2. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in the global series (n=61) (n=1), Fusarium spp. (n=2), Scedosporium apiospermum (n=2) and S. prolificans (n=1). All cases of probable IFD were aspergillosis. All patients with mucormycosis were treated with ACT and surgery, with the exception of one patient with pulmonary mucormycosis diagnosed at postmortem examination.

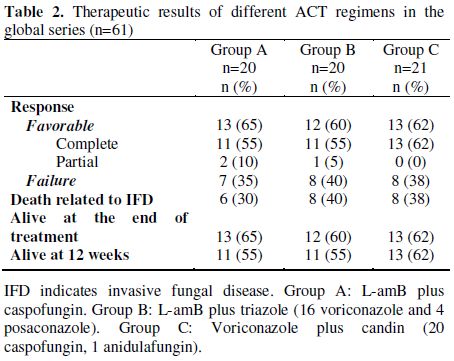

Table 2. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in the global series (n=61).

Antifungal Combination Therapy. The mean duration of ACT was 31 days (range, 8-127). Three antifungal combination groups were identified: group A, L-AmB plus caspofungin (20 patients); group B, L-AmB plus triazole (voriconazole 16 and posaconazole 4) and group C, voriconazole plus candin (20 caspofungin and 1 anidulafungin).

Toxicity. ACT was well tolerated except for a mild increase in liver enzymes in patients receiving voriconazole and a mild increase in serum creatinine levels in two patients receiving L-AmB. In one case, L-AmB treatment was discontinued for two days returning the serum creatinine level to normal following a dose reduction from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg/day for two additional days. Hypokalemia was observed in patients receiving L-AmB, but they responded well to potassium supplements.

Outcome. Thirty-eight patients had a favorable response to ACT [35 complete response (CR) and 3 partial responses (PR)]. The survival rate at the end of treatment was 62% for the whole series and the 12-week survival rate after initiation of ACT was 57%.

In group A, 13 (65%) patients had favorable response (11 CR, 2 PR), in group B, 12 (60%) patients (11 CR, 1 PR response) and in group C, 13 (62%) patients (13 CR). We found no statistical differences in terms of clinically favorable responses among groups A, B and C (Table 2).

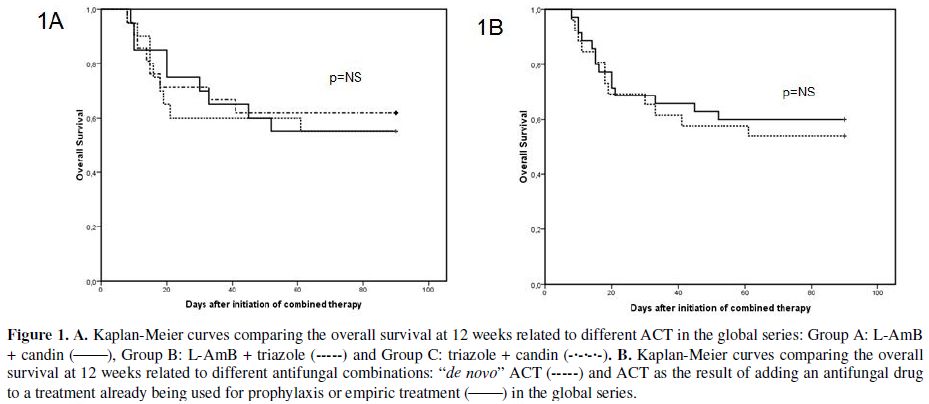

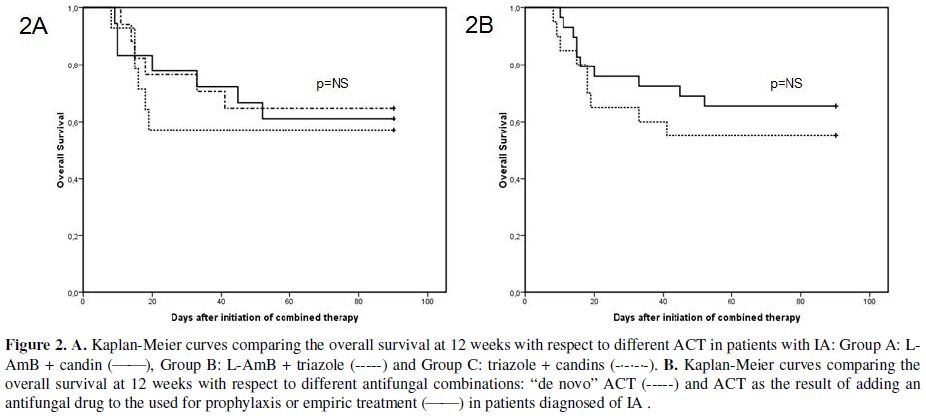

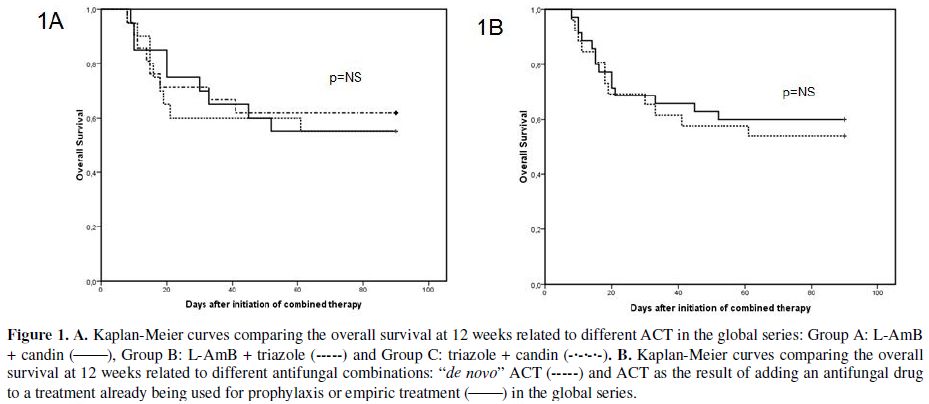

Survival rates at the end of treatment for groups A, B and C were 65%, 60% and 62%, respectively. The probability of survival at 12 weeks for groups A, B, and C were 55%, 55% and 62%, respectively (Figure 1A). We found no significant differences in the probability of survival at 12 weeks between patients treated with de novo ACT compared with those treated with sequential ACT through addition of another antifungal agent to previous prophylaxis or empiric therapy (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. A. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks related to different ACT in the global series: Group A: L-AmB + candin (_____), Group B: L-AmB + triazole (-----) and Group C: triazole + candin (-•-•-•-). B. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks related to different antifungal combinations: “de novo” ACT (-----) and ACT as the result of adding an antifungal drug to a treatment already being used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment (_____) in the global series.

A total of 20 out of 27 patients (74%) receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy for AML achieved a favorable response to ACT while a favorable response occurred in only 14 out of 25 recipients of allo-SCT (56%). Survival at 12 weeks was higher in AML (64%) compared to allo-SCT (52%). However these differences were not statistically significant.

Twenty-three patients died. Deaths were related to IFD alone (n=8), IFD in the setting of progressive underlying disease (n=14), and cytomegalovirus infection plus acute GvHD (n=1). From the end of the combined treatment to 12 weeks after the initiation of ACT, 3 additional patients died due to chronic GvHD (n=1) and leukemia relapse (n=2). IFD-related mortality at 12 weeks was 39%.

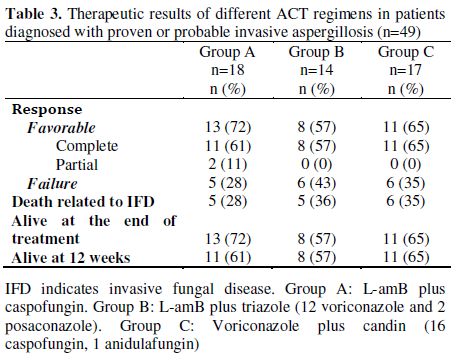

Antifungal Combination Therapy in Aspergillosis. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) was diagnosed in 49 patients (13 proven and 36 probable). A total of 32 (65%) patients responded favorably to treatment (30 CR and 2 PR), and the end of treatment and 12-week survival rates were 65% and 61%, respectively.

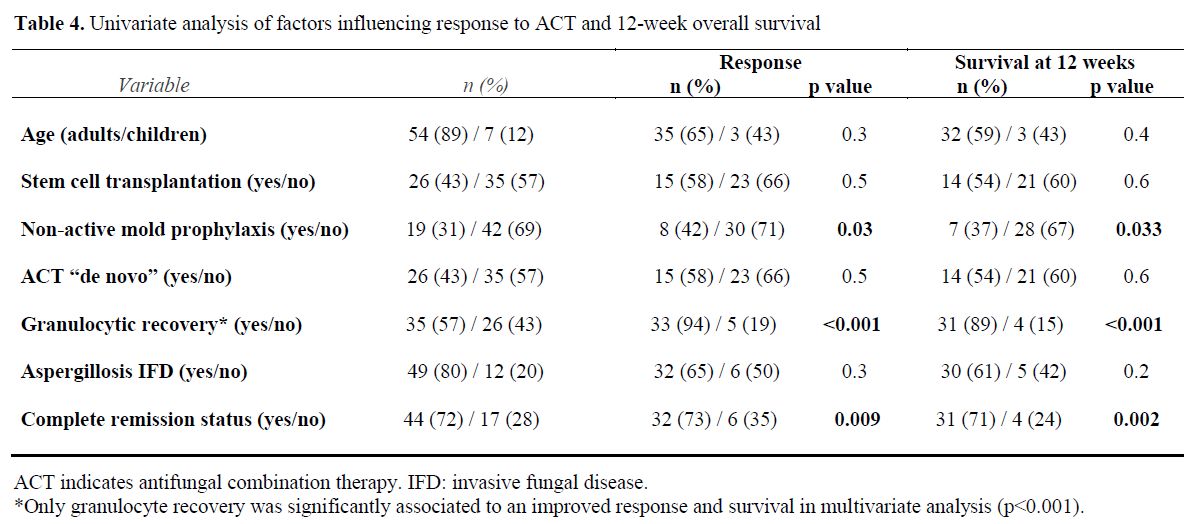

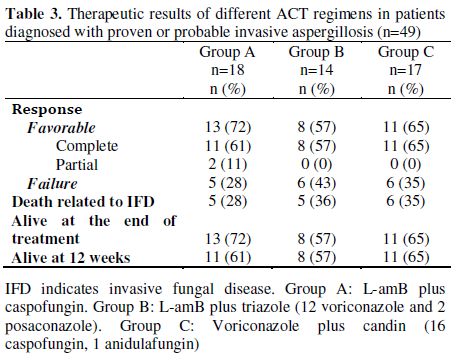

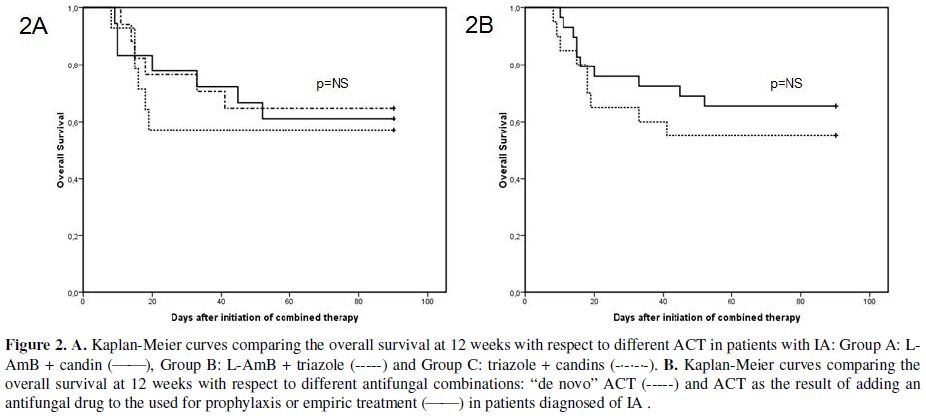

In group A, 13 of 18 patients (72%) responded (11 CR and 2 PR), in group B, 8 of 14 patients (57%, 8 CR) and in group C, 11 of 17 patients (65%, 11 CR). We found no statistical difference between response rates among groups A, B and C (Table 3). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in survival at 12 weeks among groups A, B and C (Figure 2A). Moreover, no significant differences were observed between patients treated with de novo ACT and those with sequential ACT (Figure 2B). The probability of death at 12 weeks attributable to IA was found to be 34%.

Table 3. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in patients diagnosed with proven or probable invasive aspergillosis (n=49).

Figure 2. A. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks with respect to different ACT in patients with IA: Group A: L-AmB + candin (_____), Group B: L-AmB + triazole (-----) and Group C: triazole + candins (-•-•-•-). B. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks with respect to different antifungal combinations: “de novo” ACT (-----) and ACT as the result of adding an antifungal drug to the used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment (_____) in patients diagnosed of IA.

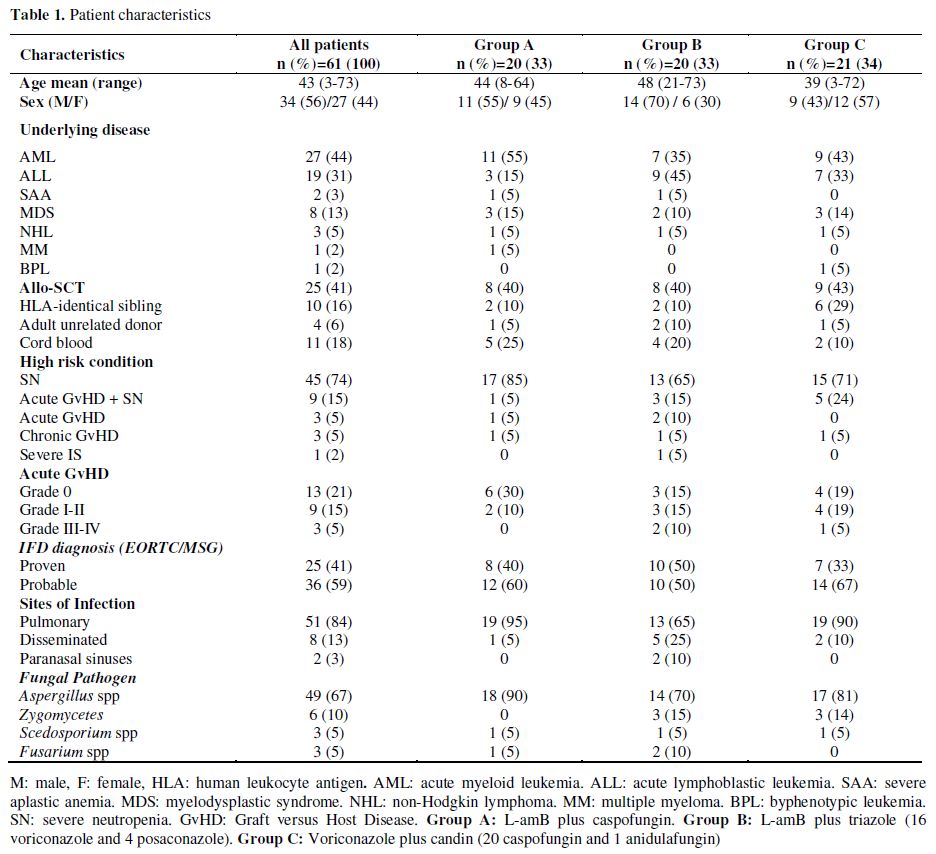

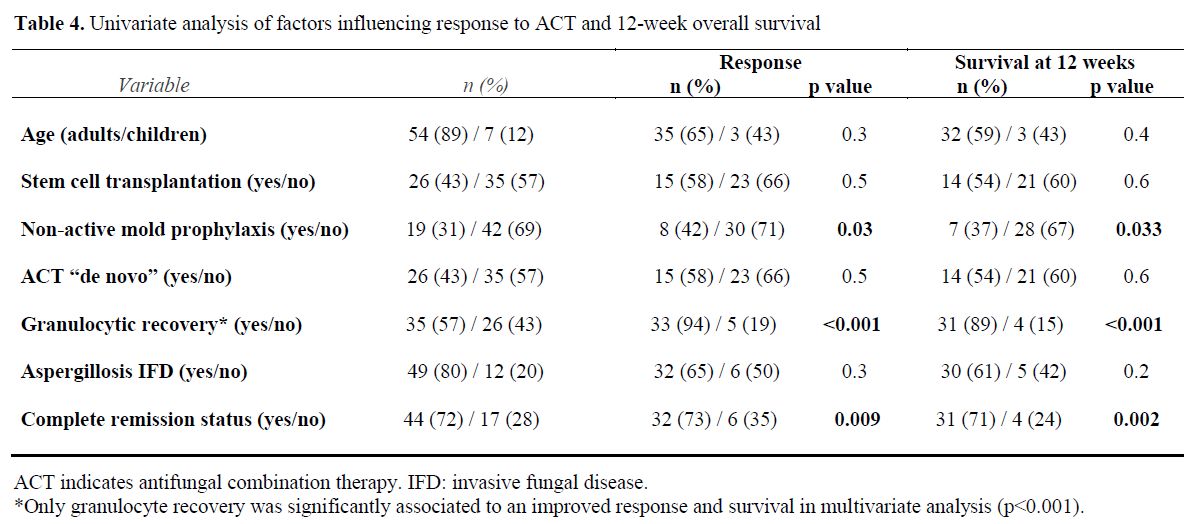

Analysis of Prognostic Factors. Univariate analysis revealed that the use of non-active mold prophylaxis (fluconazole or no prophylaxis) influenced unfavorably the ACT response (p=0.03) and mortality (p=0.03), while granulocyte recovery and complete remission of the underlying malignancy improved the response to ACT (p<0.001 and p=0.009, respectively) and decreased mortality (p<0.001 and p=0.002 respectively). Other clinical variables such as age, stem cell transplantation, de novo ACT and IA did not show significant influence on response or mortality. Logistic regression multivariate analysis revealed that granulocytic recovery was the only statistically significant variable (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of factors influencing response to ACT and 12-week overall survival.

When we analyzed these variables separately in groups A, B and C only granulocyte recovery was statistically significant for response (p=0.004 and p=0.02 for group A and B, respectively) and survival at 12 weeks (p=0.02 and p=0.007 for group A and B, respectively). In group C all patients with no granulocyte recovery died.

Discussion.

This study shows that ACT seems to be suitable for the treatment of IFD in severely immunocompromised patients.[20-23] Our results are in line with those previously reported.[24-31] It should be noted that the three types of ACT employed in our patients resulted in similar response rates in both the overall series and in patients with IA. These findings do not support the results that in both in vitro and animal models have been reported.[35,36] These studies have suggested an antagonism with the combination of L-AmB and voriconazole. Probably, as Segal & Steinbach[37] have stated, a major limitation in the antifungal field is the lack of consistent ability to use in vitro models to predict clinical efficacy. In general, antagonism has not been apparent in the clinical setting. In fact, a recent study by Cornely et al[38] suggested that prior azole prophylaxis or therapy did not affect overall response nor mortality in patients who were treated with L-AmB for IMI (49% response rate in patients given previously azoles vs. 46% in those without prior azole exposure). Survival at 12 weeks was also similar (64% vs. 66%).

Although our study is not a prospectively randomized trial, we believe it provides valuable information on the potential impact of ACT in seriously ill patients with hematological diseases. In fact, as far as we know, the only prospective randomized trial reported is a pilot study by Caillot et al.[31] which included a small number of patients (15 patients in each arm). High dose L-AmB (10 mg⁄kg⁄day) was compared with a combination of standard dose L-AmB (3 mg/kg⁄day) plus caspofungin in 30 patients with hematologic malignancies and proven or probable invasive aspergillosis (COMBISTRAT trial). Response rates at the end of treatment were 67% for the combination vs. 27% with monotherapy (p= 0.03). Survival rates at 12 weeks were similar, 100% for the combination and 80% for monotherapy. Nevertheless, this study indicated the superiority of standard L-AmB plus caspofungin over high-dose L-AmB monotherapy, which in addition had a higher toxicity. On the other hand, the consistently better results in most retrospective case studies using ACT in the treatment of probable and proven IFD are similar to those obtained in the present study.[24-31]

An increasing number of patients with IFD and life-threatening conditions can be cured with ACT when the underlying disease is under control. It should be noted that, in our case series, as in other published reports,39 ACT was well tolerated with only minor toxicity. In contrast, some case series in which single drugs were used had similar or higher toxicity than those reported in the present study.[20,22] However, retrospective studies usually suffer from potential bias. For instance, in our study only patients who survived at least 7 days from the start of ACT were considered for analysis, and consequently, patients with very severe infections may have been excluded from the study. This criticism may be applied to most clinical trials that exclude patients with poor performance status (ECOG 2), life-expectancy less than one week or severe organ dysfunction.

Regarding prognostic factors, granulocyte recovery resulting from the control of the underlying disease is the most important variable in IFD patients regardless of the ACT used. The use of ACT instead of monotherapy may more efficiently stabilize the IFD, preventing fatal progression while neutrophil counts recover and the immune system is restored. This finding raises again the question about the potential utility of granulocyte transfusions as adjunctive treatment. After years of controversy, the RING (Resolving Infections in Neutropenia with Granulocytes) study has been designed to evaluate the effectiveness of transfusing large numbers of G-CSF/dexamethasone mobilized granulocytes from community donors. When available, the results of this multicenter phase III randomized controlled clinical trial may be of great value to definitely address this unresolved issue.[40]

Conflict of Interest Disclosures.

R. Rojas has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science and Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD). JR. Molina has received honoraria for speaking at medical education events supported by Gilead Science and Pfizer. I. Jarque has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead Science. J. Besalduch receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science. E. Carreras receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science, Pfizer and MSD. JF. Tomas receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science, MSD and Pfizer. L. Madero receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead, Pfizer and MSD. D. Rubio has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science, Pfizer and MSD. E. Conde has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science and MSD. MA. Sanz has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Pfizer, (MSD), and Gilead Science and has sat on advisory boards on antifungal agents for Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead Science. A. Torres has received honoraria for participation as speaker at medical education and symposia events supported by Gilead, Pfizer and MSD. C. Montes, J. Serrano and J. Sanz declare no competing financial interest.

Severe neutropenia and immunosuppression resulting from the use of high-dose chemotherapy in hematological diseases followed, in selected cases, by allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT), increase the susceptibility of patients to invasive fungal disease (IFD). The growing use of these aggressive therapies has led to a remarkable increase in the incidence of IFD.[1-3] Although fluconazole prophylaxis has reduced yeast infections in these vulnerable populations, invasive mold infections (IMI), particularly those caused by Aspergillus spp, have steadily increased to a 10-20% incidence rate. Furthermore, a high mortality rate for aspergillosis, the most common IMI, has been described, especially among allo-SCT recipients.[1-5] In addition, zygomycosis can reach attributable mortality rates of 91% in these patients.[6]

Many attempts have been made to decrease the incidence and mortality of IFD in patients with hematological malignancies. Strategies including empiric therapy, [7-9] pre-emptive treatment[10-13] and improved prophylactic regimens with new azoles have been proposed.[14-19] Monotherapy with new antifungal agents such as candins, triazoles and liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) has also been used as treatment for proven or probable IFD.[20-23] However, though improved survival rates have been documented with the use of these individual agents, overall response and treatment outcome remain suboptimal in cases of IMI with high mortality rates.

Recently, several retrospective or uncontrolled clinical reports[24-30] and, as far as we know, only one prospective randomized study[31] have addressed the potential benefit of using combinations of new antifungal agents in the treatment of IFD. This issue is conceptually promising, because an additive activity or even synergy of antifungal drugs might be expected.[32] Although these studies provide evidence supporting the use of this approach, the advantages of combined therapy have not yet been clearly demonstrated.[25-32] Therefore, it is still unclear if antifungal combined therapy (ACT) is superior to monotherapy in severely neutropenic and/or immunocompromised patients with life-threatening IFD.

In this retrospective, observational, multicenter study, we describe the results of ACT in 61 proven or probable cases of IMI occurring in high-risk hematological patients treated with intensive chemotherapy or allo-SCT.

Patients and Methods.

We have retrospectively analyzed all consecutive cases of high-risk hematological patients with proven or probable IMI treated with ACT in eight tertiary university hospitals in Spain over a 5-year period (January 2005 - December 2009). For inclusion in the analysis, patients must have received at least seven days of ACT. Antifungal agents used as primary prophylaxis, empiric treatments or in ACT depended on the specific policies of participating hospitals.

Definitions. Diagnosis of IMI was established according to the revised EORTC/MSG criteria.33 Responses to antifungal therapy were defined according to the MSG/EORTC consensus criteria34 as either favorable response (complete or partial) or failure (stable disease, progression or death from any cause).

Prophylaxis was defined as primary when patients did not have a previous history of IFD, while it was defined as secondary in patients with a previous IFD history but no signs or symptoms of fungal infection when the new hematological treatment was initiated.

ACT was started when the diagnosis of proven or probable IFD was made. The following doses were used in the treatment of adult patients: voriconazole, loading dose of 6 mg/kg/12 hours x 2 doses followed by 4 mg/kg/12 hours; posaconazole, 400 mg/12 hours; caspofungin, 70 mg on day 1 and 50 mg/day starting from day 2; anidulafungin, 200 mg on day 1 and 100 mg/day after and L-AmB, 3 mg/kg/day. The doses used in the treatment of children were: voriconazole, 7 mg/kg/12 hours; caspofungin, 70 mg/m2 (maximum 70 mg) on the first day and 50 mg/m2 (maximum 50 mg) each subsequent day and L-AmB, 3 mg/kg/day. All drugs were given intravenously but posaconazole was administered orally. Azole plasma levels were not monitored.

De novo ACT was defined as the combination of two antifungal drugs not used before for prophylaxis or empiric treatment. Sequential ACT occurred when an antifungal drug was added to another already being used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment.

Statistical Analysis. Data were collected in a SPSS database and all statistical results were performed using SPSS version 17. Either the chi-square or the Fisher’s exact test were used to compare data. Overall survival was analyzed using temporal series Kaplan-Meier analysis and comparisons between different treatments groups were performed using the log-rank test. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was used. A p value of less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results.

Patients. Sixty-one patients were included in the study. The mean age was 43 years (range, 3-73) with 7 patients younger than 18 years. Thirty-four patients had received intensive chemotherapy for induction (n=28) or consolidation (n=6). Twenty-five patients were recipients of allo-SCT and one patient received an autologous SCT. The main demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Fifty-four patients (89%) were severely neutropenic (absolute neutrophil count <500/L for at least 10 consecutive days) at the onset of IFD; of these, 9 had at the same time acute graft versus host disease (GvHD). Only 7 patients developed an IFD without severe neutropenia: 3 patients had acute GvHD, 3 patients chronic GvHD and 1 patient severe aplastic anemia under immunosuppressive treatment.

Prior antifungal prophylaxis was administered to 60 patients (23 voriconazole, 18 fluconazole, 18 itraconazole and 1 L-AmB). In 35 patients, prophylaxis was stopped when empirical antifungal treatment was initiated (9 patients were given voriconazole, 16 caspofungin and 10 L-AmB). The patient not receiving prophylaxis started empirical treatment with voriconazole. Only 3 patients with prior history of IFD (2 candidemias and 1 probable pulmonary aspergillosis) received secondary prophylaxis (1 fluconazole, 2 voriconazole).

De novo ACT was started in 26 patients. In 23 other patients, combined treatment was initiated by adding a new antifungal agent to the empirical treatment. In the remaining 12 patients, a second antifungal drug was added to the prophylaxis regimen.

The diagnosis of proven IFD was confirmed in 25 patients, while the remaining 36 patients met the criteria for probable IFD. The molds isolated in proven IFD cases were as follows: Aspergillus fumigatus (n=6), A. flavus (n=3), A. terreus (n=1), Aspergillus spp. (n=3), Mucor spp. (n=6), Fusarium oxysporum Table 2. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in the global series (n=61) (n=1), Fusarium spp. (n=2), Scedosporium apiospermum (n=2) and S. prolificans (n=1). All cases of probable IFD were aspergillosis. All patients with mucormycosis were treated with ACT and surgery, with the exception of one patient with pulmonary mucormycosis diagnosed at postmortem examination.

Table 2. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in the global series (n=61).

Antifungal Combination Therapy. The mean duration of ACT was 31 days (range, 8-127). Three antifungal combination groups were identified: group A, L-AmB plus caspofungin (20 patients); group B, L-AmB plus triazole (voriconazole 16 and posaconazole 4) and group C, voriconazole plus candin (20 caspofungin and 1 anidulafungin).

Toxicity. ACT was well tolerated except for a mild increase in liver enzymes in patients receiving voriconazole and a mild increase in serum creatinine levels in two patients receiving L-AmB. In one case, L-AmB treatment was discontinued for two days returning the serum creatinine level to normal following a dose reduction from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg/day for two additional days. Hypokalemia was observed in patients receiving L-AmB, but they responded well to potassium supplements.

Outcome. Thirty-eight patients had a favorable response to ACT [35 complete response (CR) and 3 partial responses (PR)]. The survival rate at the end of treatment was 62% for the whole series and the 12-week survival rate after initiation of ACT was 57%.

In group A, 13 (65%) patients had favorable response (11 CR, 2 PR), in group B, 12 (60%) patients (11 CR, 1 PR response) and in group C, 13 (62%) patients (13 CR). We found no statistical differences in terms of clinically favorable responses among groups A, B and C (Table 2).

Survival rates at the end of treatment for groups A, B and C were 65%, 60% and 62%, respectively. The probability of survival at 12 weeks for groups A, B, and C were 55%, 55% and 62%, respectively (Figure 1A). We found no significant differences in the probability of survival at 12 weeks between patients treated with de novo ACT compared with those treated with sequential ACT through addition of another antifungal agent to previous prophylaxis or empiric therapy (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. A. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks related to different ACT in the global series: Group A: L-AmB + candin (_____), Group B: L-AmB + triazole (-----) and Group C: triazole + candin (-•-•-•-). B. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks related to different antifungal combinations: “de novo” ACT (-----) and ACT as the result of adding an antifungal drug to a treatment already being used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment (_____) in the global series.

A total of 20 out of 27 patients (74%) receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy for AML achieved a favorable response to ACT while a favorable response occurred in only 14 out of 25 recipients of allo-SCT (56%). Survival at 12 weeks was higher in AML (64%) compared to allo-SCT (52%). However these differences were not statistically significant.

Twenty-three patients died. Deaths were related to IFD alone (n=8), IFD in the setting of progressive underlying disease (n=14), and cytomegalovirus infection plus acute GvHD (n=1). From the end of the combined treatment to 12 weeks after the initiation of ACT, 3 additional patients died due to chronic GvHD (n=1) and leukemia relapse (n=2). IFD-related mortality at 12 weeks was 39%.

Antifungal Combination Therapy in Aspergillosis. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) was diagnosed in 49 patients (13 proven and 36 probable). A total of 32 (65%) patients responded favorably to treatment (30 CR and 2 PR), and the end of treatment and 12-week survival rates were 65% and 61%, respectively.

In group A, 13 of 18 patients (72%) responded (11 CR and 2 PR), in group B, 8 of 14 patients (57%, 8 CR) and in group C, 11 of 17 patients (65%, 11 CR). We found no statistical difference between response rates among groups A, B and C (Table 3). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in survival at 12 weeks among groups A, B and C (Figure 2A). Moreover, no significant differences were observed between patients treated with de novo ACT and those with sequential ACT (Figure 2B). The probability of death at 12 weeks attributable to IA was found to be 34%.

Table 3. Therapeutic results of different ACT regimens in patients diagnosed with proven or probable invasive aspergillosis (n=49).

Figure 2. A. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks with respect to different ACT in patients with IA: Group A: L-AmB + candin (_____), Group B: L-AmB + triazole (-----) and Group C: triazole + candins (-•-•-•-). B. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the overall survival at 12 weeks with respect to different antifungal combinations: “de novo” ACT (-----) and ACT as the result of adding an antifungal drug to the used for prophylaxis or empiric treatment (_____) in patients diagnosed of IA.

Analysis of Prognostic Factors. Univariate analysis revealed that the use of non-active mold prophylaxis (fluconazole or no prophylaxis) influenced unfavorably the ACT response (p=0.03) and mortality (p=0.03), while granulocyte recovery and complete remission of the underlying malignancy improved the response to ACT (p<0.001 and p=0.009, respectively) and decreased mortality (p<0.001 and p=0.002 respectively). Other clinical variables such as age, stem cell transplantation, de novo ACT and IA did not show significant influence on response or mortality. Logistic regression multivariate analysis revealed that granulocytic recovery was the only statistically significant variable (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of factors influencing response to ACT and 12-week overall survival.

When we analyzed these variables separately in groups A, B and C only granulocyte recovery was statistically significant for response (p=0.004 and p=0.02 for group A and B, respectively) and survival at 12 weeks (p=0.02 and p=0.007 for group A and B, respectively). In group C all patients with no granulocyte recovery died.

Discussion.

This study shows that ACT seems to be suitable for the treatment of IFD in severely immunocompromised patients.[20-23] Our results are in line with those previously reported.[24-31] It should be noted that the three types of ACT employed in our patients resulted in similar response rates in both the overall series and in patients with IA. These findings do not support the results that in both in vitro and animal models have been reported.[35,36] These studies have suggested an antagonism with the combination of L-AmB and voriconazole. Probably, as Segal & Steinbach[37] have stated, a major limitation in the antifungal field is the lack of consistent ability to use in vitro models to predict clinical efficacy. In general, antagonism has not been apparent in the clinical setting. In fact, a recent study by Cornely et al[38] suggested that prior azole prophylaxis or therapy did not affect overall response nor mortality in patients who were treated with L-AmB for IMI (49% response rate in patients given previously azoles vs. 46% in those without prior azole exposure). Survival at 12 weeks was also similar (64% vs. 66%).

Although our study is not a prospectively randomized trial, we believe it provides valuable information on the potential impact of ACT in seriously ill patients with hematological diseases. In fact, as far as we know, the only prospective randomized trial reported is a pilot study by Caillot et al.[31] which included a small number of patients (15 patients in each arm). High dose L-AmB (10 mg⁄kg⁄day) was compared with a combination of standard dose L-AmB (3 mg/kg⁄day) plus caspofungin in 30 patients with hematologic malignancies and proven or probable invasive aspergillosis (COMBISTRAT trial). Response rates at the end of treatment were 67% for the combination vs. 27% with monotherapy (p= 0.03). Survival rates at 12 weeks were similar, 100% for the combination and 80% for monotherapy. Nevertheless, this study indicated the superiority of standard L-AmB plus caspofungin over high-dose L-AmB monotherapy, which in addition had a higher toxicity. On the other hand, the consistently better results in most retrospective case studies using ACT in the treatment of probable and proven IFD are similar to those obtained in the present study.[24-31]

An increasing number of patients with IFD and life-threatening conditions can be cured with ACT when the underlying disease is under control. It should be noted that, in our case series, as in other published reports,39 ACT was well tolerated with only minor toxicity. In contrast, some case series in which single drugs were used had similar or higher toxicity than those reported in the present study.[20,22] However, retrospective studies usually suffer from potential bias. For instance, in our study only patients who survived at least 7 days from the start of ACT were considered for analysis, and consequently, patients with very severe infections may have been excluded from the study. This criticism may be applied to most clinical trials that exclude patients with poor performance status (ECOG 2), life-expectancy less than one week or severe organ dysfunction.

Regarding prognostic factors, granulocyte recovery resulting from the control of the underlying disease is the most important variable in IFD patients regardless of the ACT used. The use of ACT instead of monotherapy may more efficiently stabilize the IFD, preventing fatal progression while neutrophil counts recover and the immune system is restored. This finding raises again the question about the potential utility of granulocyte transfusions as adjunctive treatment. After years of controversy, the RING (Resolving Infections in Neutropenia with Granulocytes) study has been designed to evaluate the effectiveness of transfusing large numbers of G-CSF/dexamethasone mobilized granulocytes from community donors. When available, the results of this multicenter phase III randomized controlled clinical trial may be of great value to definitely address this unresolved issue.[40]

Conflict of Interest Disclosures.

R. Rojas has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science and Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD). JR. Molina has received honoraria for speaking at medical education events supported by Gilead Science and Pfizer. I. Jarque has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead Science. J. Besalduch receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science. E. Carreras receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science, Pfizer and MSD. JF. Tomas receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead Science, MSD and Pfizer. L. Madero receives honoraria for participation as a speaker at medical education events supported by Gilead, Pfizer and MSD. D. Rubio has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science, Pfizer and MSD. E. Conde has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Gilead Science and MSD. MA. Sanz has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Pfizer, (MSD), and Gilead Science and has sat on advisory boards on antifungal agents for Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead Science. A. Torres has received honoraria for participation as speaker at medical education and symposia events supported by Gilead, Pfizer and MSD. C. Montes, J. Serrano and J. Sanz declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Marr

KA, Carter RA, Boeckh M, Martin P, Corey L. Invasive aspergillosis in

allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients; Changes in

epidemiology and risk factors. Blood 2002; 100: 4358-4366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-05-1496 PMid:12393425

- Sanz MA, Jarque I, Salavert M, Pemán J.

Epidemiology of invasive fungal infections due to Aspergillus spp. and

Zygomycetes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006; 12 (Suppl 7): 2-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01602.x

- Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach

W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, Pfaller M, Chang C, Webster K, Marr K.

Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult

hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter

Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance registry. Clin Infect

Dis 2009;48:265-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/595846 PMid:19115967

- Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM.

Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature.

Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32: 358-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/318483 PMid:11170942

- Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M,

Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell

transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with

mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:531-540. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/510592 PMid:17243056

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen

TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, Sein M, Sein T, Chiou CC, Chu JH,

Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a

review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41: 634-653. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/432579 PMid:16080086

- Walsh TJ, Finberg RW, Arndt C, Hiemenz J,

Schwartz C, Bodensteiner D, Pappas P, Seibel N, Greenberg RN, Dummer S,

Schuster M, Holcenberg JS. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

Diseases Mycoses Study Group. Liposomal amphotericin B for empirical

therapy in patients with persistent fever and neutropenia. N Engl J Med

1999; 340: 764-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199903113401004 PMid:10072411

- Walsh TJ, Pappas P, Winston DJ, Petersen F,

Raffalli J, Yanovich S, Stiff P, Greenberg R, Donowitz G, Schuster M,

Reboli A, Wingard J, Arndt C, Reinhardt J, Hadley S, Finberg R,

Laverdière M, Perfect J, Garber G, Fioritoni G, Anaissie E, Lee J.

Voriconazole compared with liposomal amphotericin B for empirical

antifungal therapy in patients with neutropenia and persistent fever. N

Engl J Med 2002; 346: 225-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200201243460403 PMid:11807146

- Walsh TJ, Teppler H, Donowitz GR, Maertens

JA, Baden LR, Dmoszynska A, Cornely OA, Bourque MR, Lupinacci RJ, Sable

CA, dePauw BE. Caspofungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for

empirical antifungal therapy in patients with persistent fever and

neutropenia. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1391-1402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040446 PMid:15459300

- Maertens J, Theunissen K, Verhoef G,

Verschakelen J, Lagrou K, Verbeken E, Wilmer A, Verhaegen J, Boogaerts

M, Van Eldere J. Galactomannan and computer tomography-based preemptive

antifungal therapy in neutropenic patients at high risk for invasive

fungal infection: A prospective feasibility study. Clin Infect Dis

2005; 41: 1242-1250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/496927 PMid:16206097

- Cordonnier C, Pautas C, Maury S, Vekhoff

A, Farhat H, Suarez F, Dhédin N, Isnard F, Ades L, Kuhnowski F, Foulet

F, Kuentz M, Maison P, Bretagne S, Schwarzinger M. Empirical versus

preemptive antifungal therapy for high-risk, febrile, neutropenic

patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;

48:1042-1051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/597395 PMid:19281327

- Girmenia C, Micozzi A, Gentile G, Santilli

S, Arleo E, Cardarelli L, Capria S, Minotti C, Cartoni C, Brocchieri S,

Guerrisi V, Meloni G, Foà R, Martino P. Clinically driven diagnostic

antifungal approach in neutropenic patients: a prospective feasibility

study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:667-674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8032 PMid:19841328

- Pagano L, Caira M, Nosari A, Cattaneo C,

Fanci R, Bonini A, Vianelli N, Garzia MG, Mancinelli M, Tosti ME,

Tumbarello M, Viale P, Aversa F, Rossi G; HEMA e-Chart Group. The use

and efficacy of empirical versus pre-emptive therapy in the management

of fungal infections: the HEMA e-Chart Project. Haematologica

2011;96:1366-1370. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.042598 PMid:21565903 PMCid:3166108

- Winston DJ, Maziarz RT, Chandrasekar PH,

Lazarus HM, Goldman M, Blumer JL, Leitz GJ, Territo MC. Intravenous and

oral itraconazole versus intravenous and oral fluconazole for long-term

antifungal prophylaxis in allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplant

recipients: a multicenter, radomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:

705-713. PMid:12729424

- Siwek GT, Pfaller MA, Polgreen PM, Cobb S,

Hoth P, Magalheas-Silverman M, Diekema DJ. Incidence of invasive

aspergillosis among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant

patients receiving voriconazole prophylaxis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis

2006; 55: 209-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.01.018 PMid:16626917

- Wingard JR, Carter SL, Walsh TJ, Kurtzberg

J, Small TN, Baden LR, Gersten ID, Mendizabal AM, Leather HL, Confer

DL, Maziarz RT, Stadtmauer EA, Bolaños-Meade J, Brown J, Dipersio JF,

Boeckh M, Marr KA. Randomized double-blind trial of fluconazole versus

voriconazole for prevention of invasive fungal infection after

allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2010; 116:

5111-5118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-02-268151 PMid:20826719 PMCid:3012532

- Torres A, Serrano J, Rojas R, Martín V,

Martín C, Tabares S, Molina JR, Capote M, Martínez F, Gómez P,

Sánchez-García J. Voriconazole as primary antifungal prophylaxis in

patients with neutropenia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

or chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Eur J Haematol 2009; 84:

271-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01367.x PMid:19878274

- Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ,

Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, Helfgott D, Holowiecki J, Stockelberg

D, Goh YT, Petrini M, Hardalo C, Suresh R, Angulo-Gonzalez D.

Posaconazole vs fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients

with neutropenia. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 348-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061094 PMid:17251531

- Ullmann AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH,

Chandrasekar P, Langston A, Tarantolo SR, Greinix H, Morais de Azevedo

W, Reddy V, Boparai N, Pedicone L, Patino H, Durrant S. Posaconazole or

fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N Engl

J Med 2007; 356: 335-347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061098 PMid:17251530

- Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF,

Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P,

Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH, Wingard JR, Stark P, Durand C,

Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF,

de Pauw B. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of

invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 408-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020191 PMid:12167683

- Van Burik JA, Perfect J, Louie A, Graybill

JR, Pedicone L, Raad II. Efficacy of posaconazole (POS) vs standard

therapy and safety of POS in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)

recipients vs other patients with aspergillosis. Biol Blood Marrow

Transplant 2006; 12 (Suppl 1): 137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.420

- Denning DW, Ribaud P, Milpied N, Caillot

D, Herbrecht R, Thiel E, Haas A, Ruhnke M, Lode H. Efficacy and safety

of voriconazole in the treatment of acute invasive aspergillosis. Clin

Infect Dis. 2002; 44: 2-12.

- Denning DW, Marr KA, Lau WM, Facklam DP,

Ratanatharathorn V, Becker C, Ullmann AJ, Seibel NL, Flynn PM, van

Burik JA, Buell DN, Patterson TF. Micafungin (FK463), alone or in

combination with other systemic antifungal agents, for the treatment of

acute invasive aspergillosis. J Infect. 2006; 53: 337-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2006.03.003 PMid:16678903

- Kontoyiannis DP, Hachem R, Lewis RE,

Rivero GA, Torres HA, Thornby J, Champlin R, Kantarjian H, Bodey GP,

Raad II. Efficacy and toxicity of caspofungin in combination with

liposomal amphotericin B as primary or salvage treatment of invasive

aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Cancer 2003;

98: 292-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11479 PMid:12872348

- Aliff TB, Maslak PG, Jurcic JG, Heaney ML,

Cathcart KN, Sepkowitz KA, Weiss MA. Refractory aspergillus pneumonia

in patients with acute leukemia. Cancer 2003; 97: 1025-1032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11115 PMid:12569602

- Marr KA, Boeckh M, Carter RA, Kim HW,

Corey L. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis.

Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 797-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/423380 PMid:15472810

- Singh N, Limaye AP, Forrest G, Safdar N,

Muñoz P, Pursell K, Houston S, Rosso F, Montoya JG, Patton P, Del Busto

R, Aguado JM, Fisher RA, Klintmalm GB, Miller R, Wagener MM, Lewis RE,

Kontoyiannis DP, Husain S. Combination of voriconazole and caspofungin

as primary therapy for invasive aspergillosis in solid organ transplant

recipients: A prospective multicenter, observational study.

Transplantation 2006; 81: 320-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000202421.94822.f7 PMid:16477215

- Maertens J, Glasmacher A, Herbrecht R,

Thiebaut A, Cordonnier C, Segal BH, Killar J, Taylor A, Kartsonis N,

Patterson TF, Aoun M, Caillot D, Sable C. Multicenter, noncomparative

study of caspofungin in combination with others antifungals as salvage

therapy in adults with invasive aspergillosis. Cancer 2006; 107:

2888-2897. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22348 PMid:17103444

- Cesaro S, Giacchino M, Locatelli F,

Spiller M, Buldini B, Castellini C, Caselli D, Giraldi E, Tucci F,

Tridello G, Rossi MR, Castagnola E. Safety and efficacy of a

caspofungin-based combination therapy for treatment of proven or

probable aspergillosis in pediatric hematological patients. BMC Infect

Dis 2007; 7: 28-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-7-28 PMid:17442100 PMCid:1871594

- Rieger CT, Ostermann H, Kolb HJ, Fiegl M,

Huppmann S, Morgenstern N, Tischer J. A clinical cohort trial of

antifungal combination therapy: Efficacy and toxicity in hematological

cancer patients. Ann Hematol 2008; 87: 915-922. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00277-008-0534-4 PMid:18641986

- Caillot D, Thiebaut A, Herbrecht R, de

Botton S, Pigneux A, Bernard F, Larché J, Monchecourt F, Alfandari S,

Mahi L. Liposomal amphotericin B in combination with caspofungin for

invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. A

randomized pilot study (Combistrat trials). Cancer 2007; 110: 2740-2746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23109 PMid:17941026

- Johnson MD, Perfect JR. Use of antifungal combination therapy: agents, order, and timing. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2010;4:87-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12281-010-0018-6 PMid:20574543 PMCid:2889487

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens

DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O,

Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes

WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P,

Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell

TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE. Revised definitions

of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research

and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group

and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses

Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:

1813-1821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/588660 PMid:18462102 PMCid:2671227

- Segal BH, Herbrecht R, Stevens DA,

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Sobel J, Viscoli C, Walsh TJ, Maertens J,

Patterson TF, Perfect JR, Dupont B, Wingard JR, Calandra T, Kauffman

CA, Graybill JR, Baden LR, Pappas PG, Bennett JE, Kontoyiannis DP,

Cordonnier C, Viviani MA, Bille J, Almyroudis NG, Wheat LJ, Graninger

W, Bow EJ, Holland SM, Kullberg BJ, Dismukes WE, De Pauw BE. Defining

responses to therapy and study outcomes in clinical trials of invasive

fungal diseases: Mycoses Study Group and European Organization for

Research and Treatment of Cancer Consensus Criteria. Clin Infect Dis

2008; 47: 674-683. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/590566 PMid:18637757 PMCid:2671230

- Sugar AM. Use of amphotericin B with azole

antifungal drugs: what are we doing? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;

39:1907-1912. PMid:8540690 PMCid:162855

- Denning DW, Hanson LH, Perlman AM, Stevens

DA. In vitro susceptibility and synergy studies of Aspergillus species

to conventional and new agents. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1992; 15:

21-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0732-8893(92)90053-V

- Segal BH, Steinbach WJ. Combination antifungals: an update. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2007; 5: 883-892. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14787210.5.5.883 PMid:17914921

- Cornely OA, Maertens J, Bresnik M, Ullmann

AJ, Ebrahimi R, Herbrecht R. Treatment outcome of invasive mould

disease after sequential exposure to azoles and liposomal amphotericin

B. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:114-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkp397 PMid:19887460

- Cetkovsky P, Kouba M, Markova M, Kolar M,

Hricinova M, Mertova J, Salek C, Vitek A, Cermak J, Soukup P.

Combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin as primary therapy in

hematologic patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010; 16: S264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.328

- Dale DC, Price TH. Granulocyte transfusion therapy: a new era? Curr Opin Hematol 2009;16:1-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MOH.0b013e32831d7953 PMid:19057197 PMCid:2674763