The Use of Monoclonal Antibodies in the Treatment of Autoimmune Complications of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Luca Laurenti1, Barbara Vannata1, Idanna Innocenti1, Francesco Autore1, Francesco Santini1, Simona Sica1 and Dimitar G Efremov2

1 Department of Hematology, Catholic University of Rome, “A. Gemelli” Hospital, Largo A. Gemelli 8, Rome, Italy.

2 Department of Molecular Hematology, International Centre for Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology, Campus A. Buzzati-Traverso, Rome, Italy.

2 Department of Molecular Hematology, International Centre for Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology, Campus A. Buzzati-Traverso, Rome, Italy.

Correspondence

to:

Luca Laurenti, MD. Department of Haematology, Catholic University

Hospital "A. Gemelli", Rome, Italy. Largo A. Gemelli, 8, 00168 Roma -

Italy, Tel: +39-06-35503953, Fax: +39-06-3017319. E-mail: l.laurenti@rm.unicatt.it

Published: April 10, 2013

Received: January 15, 2013

Accepted: April 4, 2013

Meditter J Hematol Infect Dis 2013, 5(1): e2013027, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2013.027

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Autoimmune

cytopenias are a frequent complication in CLL, occurring in

approximately 5-10% of the patients. The most common manifestation is

autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, followed by immune thrombocytopenia and

only rarely pure red blood cell aplasia or autoimmune granulocytopenia.

Initial treatment is as for the idiopathic autoimmune cytopenias, with

most patients responding to conventional corticosteroid therapy.

Patients, who do not respond to conventional therapy after 4–6 weeks,

should be considered for alternative immunosuppression, monoclonal

antibody therapy or splenectomy. While randomized trials demonstrating

the benefit of rituximab in CLL-related autoimmune diseases are still

lacking, there are considerable data in the literature that provide

evidence for its effectiveness.

The monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab also displays considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complication in patients with CLL, although at the expense of greater toxicity. A number of new monoclonal antibodies, such as ofatumumab, GA-101, lumiliximab, TRU-016, epratuzumab, and galiximab, are currently investigated in CLL and their activity in CLL-related autoimmune cytopenias should be evaluated in future studies.

The monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab also displays considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complication in patients with CLL, although at the expense of greater toxicity. A number of new monoclonal antibodies, such as ofatumumab, GA-101, lumiliximab, TRU-016, epratuzumab, and galiximab, are currently investigated in CLL and their activity in CLL-related autoimmune cytopenias should be evaluated in future studies.

Introduction

Autoimmunity is more common in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders than in patients with myeloproliferative conditions (8% vs. 1.7%, respectively).[1] Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by an association with autoimmune phenomena that are stronger than in other chronic lymphoproliferative disorders.[2-7]

Epidemiological data show that the occurrence of autoimmune cytopenia during the clinical history of CLL ranges from 4.3% to 9.7%.[8-12] The most common CLL-related immune haematological disturbance is autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA), which occurs in approximately 7% of the cases.[8-10,13] An additional proportion of patients (7-14%) may have a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) without clinical evidence of haemolysis.[12] Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and autoimmune granulocytopenia are more rare than AIHA, with an estimated frequency respectively of 1-5%.[8-9,13-14] and about 1%.[15] The incidence of immune disorders involving components of the blood coagulation system, such as acquired haemophilia or acquired von Willebrand disease has not been evaluated.

Regarding the association between CLL and non-haematological autoimmune disorders, data in the literature report that the proportion of patients with clinically apparent autoimmune disease ranges from 2% to 12% while the presence of serological markers of autoimmunity ranges from 8% to 41%.[16-18] However, no significant association was observed between CLL and non-haematological autoimmune diseases in case-control studies.[4] The mechanisms responsible for the development of immune cytopenias in CLL are only partially understood:

1) CLL cells may process red blood cell antigens and act as antigen presenting cells, inducing a T-cell response and the formation of polyclonal antibodies by normal B-cell, thus indirectly provoking autoimmune haemolytic anaemia;

2) CLL cells express inhibitory cytokines which alter tolerance, facilitating the escape of self-reactive cells;

3) rarely CLL cells are effector cells, directly producing a pathological monoclonal autoantibody;

4) CLL cells may be stimulated through their polyreactive BCR which recognizes auto-antigens.[4-6]

An increased risk to develop autoimmune cytopenia has been observed in patients displaying various adverse clinical or biological prognostic features, such as advanced stage,[4,9,16,19] older age,[8,12,16] high white cell count,[8,14,17] short lymphocyte doubling time,[10,16] increased beta-2-microglobulin levels,[10,12,17] CD38[10,17] and ZAP-70 positivity,[9,14] unmutated IGVH genes and stereotyped BCRs[20-22] band poor risk cytogenetics.[9,22]

Recent data of a retrospective series of 585 CLL patients indicated that unmutated IGHV status and/or unfavorable cytogenetic lesions (del17p13 and del11q23) were significantly associated with the risk of developing secondary AIHA (p<0.0001), also suggesting a possible role of specific stereotyped B-cell receptor subsets in a proportion of cases. Stereotyped HCDR3 sequences were identified in 29.6% of cases and were similarly represented among patients developing or not AIHA; notably, a particular subset (IGHV1-69 and IGHV4-30/IGHD2-2/IGHJ6) was associated with a significantly higher risk of AIHA than the other patients (p=0.004). Multivariate analysis showed that unmutated IGHV, del17p13 and del11q23, but not this stereotyped subset, were the strongest independent variables associated with AIHA.[22]

To clarify the importance of stage and therapy for the development of autoimmune complications, the GIMEMA Group (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto) conducted a study on 194 CLL cases with autoimmune complications and 434 CLL controls:[23] AIHA (129 cases) and ITP (35 cases) were typically present in patients multi-treated and/or in advanced stage. Age over the median (>69 years), stage C, and first and second line therapy were identified as an independent risk factors by multivariate analysis. The majority of patients with AIHA were in stage C, whereas cases of ITP were equally distributed across all 3 Binet stages. Both AIHA and ITP were almost exclusively observed in patients who had received first or second line therapy for CLL. In contrast, non-hematologic autoimmune complications and the presence of serological markers of autoimmunity were mostly observed in patients with early stage CLL (stage A in 17/23 cases), suggesting that different pathogenic mechanisms underlay hematologic and non-hematologic autoimmune phenomena in CLL.

The association between treatment and development of autoimmune cytopenias, particularly AIHA, was described many years ago,[24,2,3] it was mainly observed in patients treated with the purine analogs fludarabine, cladribine and pentostatin. [25-29] However, the risk of developing autoimmune cytopenia after exposure to multi-drug regimens containing purine analogues, such as fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab, is not greater than with other agents.[10,12,30,31] An intriguing finding emerged from the UK CLL4 trial: the incidence of AIHA was significantly lower in patients treated with fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (5%) than in those allocated to receive chlorambucil (12%) or fludarabine alone (11%)(p<0.01). That suggests a possible “protective” effect of the addition of cyclophosphamide on the onset of AIHA.[12] More recent data, coming from the German CLL 8 trial, showed that the rate of AIHA in CLL patients treated with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, with or without rituximab, was only 1%.[31]

Another crucial question is if the autoimmune cytopenias confer poor prognosis in CLL. In the study of Zent et al., survival of patients with autoimmune cytopenias diagnosed within 1 year of the diagnosis of CLL was similar to survival of patients without CLL-related cytopenia (median 9.3 vs. 9.7 years, P=0.881), suggesting that cytopenia caused by autoimmune disease is not an adverse prognostic factor. In contrast, survival of patients with cytopenia due to bone marrow failure was significantly shorter (median 4.4 years, P<0.001), demonstrating the need for accurate determination of the etiology of cytopenia in the prognostic classification of patients with CLL.[9]

Treatment

The choice of treatment for autoimmune cytopenias in patients with CLL depends on whether the underlying disease also requires treatment.[32] Patients with not-progressive CLL and autoimmune cytopenia not requiring treatment for the malignant disease are usually managed in the same manner as patients with a primary autoimmune cytopenia. In contrast, CLL patients with progressive disease requiring treatment for both the underlying disease and the autoimmune cytopenia have more “complex” treatment, requiring systemic chemo-immunotherapy.[33] Most patients with AIHA are symptomatic and require therapeutic intervention; although most leukemic patients with ITP are asymptomatic and the thrombocytopenia is detected on a routine blood count,[34] they are at higher risk of bleeding than patients with the sole ITP, being frequently older. Thus, it has been recommended to initiate therapy in patients with a platelet count below 30 x 109/l also asymptomatic.[35] Patients with autoimmune cytopenia in the absence of progressive CLL should be treated with conventional therapy, i.e. oral prednisone at a daily dose of 0,5–2 mg/kg. Prednisone is tapered once a response is observed over several months; pulsed high dose dexamethasone (40 mg/d) has been also recommended in 4-day pulses every 2 weeks.[36] Up to 80% of patients will respond to corticosteroids, but many responders will remain corticosteroid-dependent.[8,9,19] Patients, who do not respond after 4–6 weeks of therapy, are unlikely to respond. They should be considered for alternative immunosuppression (e.g. cyclosporine, mycophenolate or azathioprine) or, as discussed below, splenectomy, monoclonal antibodies or other biological agents.[37,38] Intravenous immunoglobulins can be useful when a rapid response is required, e.g. in patients with ITP and significant bleeding, prior to splenectomy or in cases of fulminant haemolysis. However, they will not give a lasting effect as a single agent. The role of splenectomy is better established in ITP than in AIHA. Although in one small series, splenectomy was found to be less effective and associated with greater morbidity in AIHA patients with systemic disease, including CLL, than in patients with idiopathic AIHA.[39] A more recent study showed a high rate (67%) of complete and durable responses in CLL patients treated with laparoscopic splenectomy.[40]

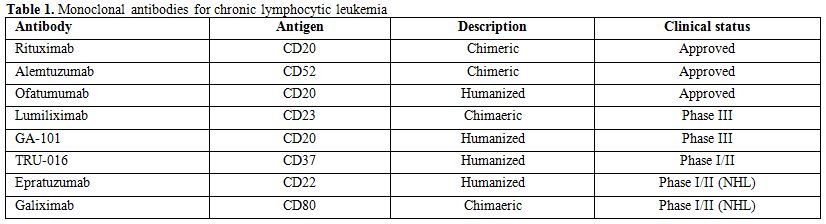

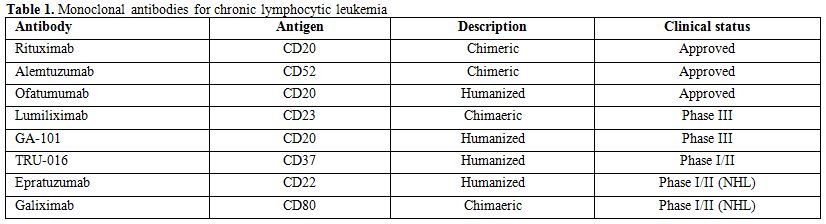

The role of the new thrombopoietin analogues romiplostim and eltrombopag in the treatment of ITP is still controversial. These agents increase platelet production rather than preventing their premature destruction.[41] The treatment should be taken indefinitely to maintain response, and their long-terms effects are largely unknown: among them, there is the marrow fibrosis. Both drugs have been demonstrated to be efficacious in resistant ITP patients after splenectomy failure and in those patients resistant, who are not surgical candidates.[42-44] Romiplostim and eltrombopag have been only occasionally reported in CLL-associated ITP treatment.[45-48] Clearly, the splenectomy in CLL-related ITP seems to have a wider role. Recently, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target normal and malignant B cells, such as rituximab and alemtuzumab, have become part of the standard treatment of CLL and are showing considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complications (Table 1).

Table 1. Monoclonal antibodies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Monoclonal Antibodies

Rituximab. Rituximab (Rituxan, Biogen IDEC, Cambridge, MA, and Mabthera, Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) is one of the first approved chimeric murine/human monoclonal IgG1 antibodies. Rituximab binds to the CD20 antigen, which is expressed on almost all B cells, and eliminates B cells through several mechanisms, including complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and induction of ‘direct cell death’ by growth inhibition and non-classic apoptosis.[49-51] mRituximab is considered to be well tolerated, nevertheless the most notable side effect is the infusion-related reaction, generally mild to moderate in severity. CLL patients with a markedly increased number of circulating lymphocytes present an increased risk of more serious adverse events, including respiratory insufficiency, tumour lysis syndrome and a rapid tumor clearance syndrome. Immunotherapy is frequently associated with grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and leucopenia while other side-effects, including severe infections, were not increased.

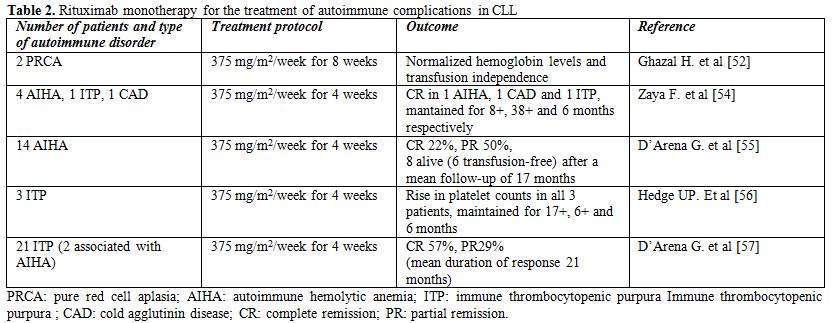

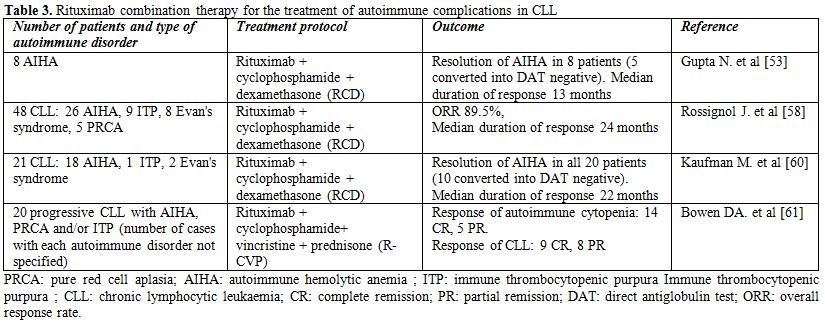

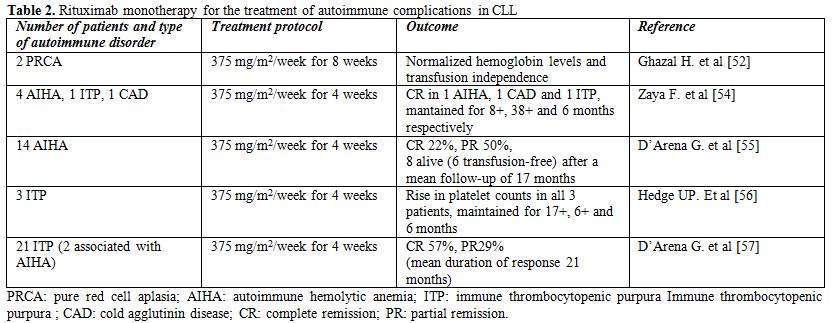

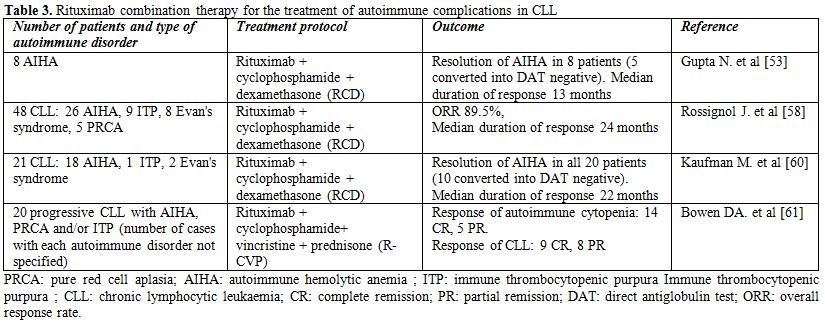

Rituximab represents one of the more active therapies for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL that do not respond to initial corticosteroid treatment (Tables 2-3). The first experience with this antibody in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune diseases was in two patients with pure red cell aplasia; both responded dramatically to rituximab treatment and became transfusion independent.[52] Subsequently, Gupta et al treated eight CLL patients with corticosteroid refractory AIHA with a combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (RCD). Cycles were repeated every 4 weeks until the best response. All eight patients achieved a remission of their AIHA and five became Coombs negative. Median duration of response was 13 months. RCD was also effective in achieving a response in patients that subsequently relapsed. [53]

Table 2. Rituximab monotherapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

Table 3. Rituximab combination therapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

Zaja et al. showed that rituximab given at the dose of 375 mg/m2 per week for 4 weeks is active in various CLL-associated autoimmune diseases that are refractory to standard immunosuppressive therapies.[54] They treated 7 patients with CLL-associated symptomatic autoimmune diseases, including four patients with warm AIHA, one patient with cold agglutinin disease (CAD), one patient with ITP, and one patient with axonal degenerating neuropathy (ADN). One of the AIHA patients and the patient with CAD achieved complete normalization of hemoglobin levels and laboratory signs of haemolysis, with response durations of 8+ and 38+ months, respectively. In the patient with ITP, complete remission was reached after the first week of treatment and the duration of response was 6 months. The patient with ADN achieved a marked neurological improvement after rituximab therapy, with response duration of 12 months.

D’Arena et al. investigated single agent rituximab in 14 patients with CLL-associated AIHA that failed first-line corticosteroid treatment.[55] Rituximab was given at a dose of 375 mg/m2/weekly for 4 weeks. A complete response was observed in 22% and a partial response in 50% of the cases. After a mean follow-up of 17 months, 8 patients were still alive, 6 of them transfusion-independent.

Hegde et al. showed that rituximab is active in CLL patients with refractory fludarabine-associated ITP.[56] Three patients who developed ITP while receiving fludarabine and who did not respond to treatment with corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) were treated with weekly rituximab (375 mg/m2 per week for 4 weeks). All patients had rapid and dramatic improvements in their platelet counts, and the response durations were 6 months or greater for all 3 patients.

In a retrospective analysis of 21 patients, D'Arena et al. showed that rituximab as a single agent (375 mg/m2/weekly for four cycles) is effective and well-tolerated treatment for CLL-related ITP refractory to corticosteroid therapy.[57] The overall response rate was 86% (57% CR, 29% PR), with a mean duration of response of 21 months. At a mean follow-up of 28 months, 66% of patients were still alive, 48% of them in CR and 14% in PR.

Recently, immunochemotherapy regimens, such as RCD or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristin and prednisone (R-CVP), have been regaining attention in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune diseases, as they can provide both anti-leukemic and anti-autoimmune effects in the absence of significant myelosuppression.[58-61] (Table 3) In the study of Kaufman et al.,[18] CLL patients with AIHA, one with ITP and two with both autoimmune diseases were treated with the RCD regimen. All CLL patients with AIHA responded to treatment with a median increase in hemoglobin of 5.2 g/dL and a median duration of response of 22 months. Nine relapsed patients responded, as well. Fifty percent of evaluable patients converted to Coombs negative, with a median duration of response of 41 months vs. 10 months for those who did not convert. All 3 patients affected with corticosteroid-refractory ITP also responded to RCD treatment.[60] Rossignol et al. reported the experience of three French university hospitals in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune disorders with the RCD protocol.[58] The study included 48 patients, among which 26 with AIHA, 9 with ITP, 8 with Evan's syndrome and 5 with PRCA, that had relapsed after previous treatment with corticosteroids, splenectomy, rituximab or alemtuzumab. The overall response rate was 89.5%, but relapses occurred in 19 patients (39.6%). The duration of response (median 24 months) was longer in patients presenting with autoimmune disease early during the course of CLL (<3 years), and in patients with PRCA and AIHA. The time to CLL progression (median of 16 months) was statistically shorter for patients with Evan's syndrome and ITP patients.

Bowen et al. treated 20 patients with progressive CLL and autoimmune cytopenia using the R-CVP protocol. A response to treatment with respect to the autoimmune cytopenia was observed in 19 patients (14 CR and 5 PR) with a median time to next treatment (TTT) for autoimmune cytopenia of 21.7 months. The progressive CLL responded in 17 patients (9 CR, 8 PR) with a median TTT of 27.7 months.[61] Grade 3-4 toxicities were infrequent and included infections (n = 3) and drug-induced pneumonitis (n = 1). Altogether, these data suggest that R-CVP is an effective and tolerable regimen for patients with autoimmune cytopenia and progressive CLL.

Alemtuzumab. The monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) is a recombinant humanized IgG1 k mAb targeting the CD52 antigen, which is expressed on normal and malignant human B and T lymphocytes, as well as natural killer cells, monocytes and macrophages.[62,63] The mechanism of action of alemtuzumab includes complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity[64] and possibly direct cytotoxicity, which has been observed in some,[65,66] but not all studies investigating this issue.[67,68]

Haematological and non-haematological toxicities such as neutropenia, lymphopenia and reactivation of herpes viruses infections, especially cytomegalovirus, are frequent after alemtuzumab therapy. Despite pre-medication with acetaminophen and diphenhydramine, intravenous administration is associated with adverse infusion reactions in 90% of patients, often severe; fever has been noted in 85% of patients frequently coupled with nausea, vomiting and rash. Considering the high risk of adverse infusion events when administered intravenously and the comparable biological activity of subcutaneous alemtuzumab associated to a decreased number of infusion reactions, subcutaneously route of administration has progressively increased.

Immunological recovery after alemtuzumab therapy showed a constant long lasting immune depletion with reduced counts of all lymphoid subsets, especially CD4+ lymphocytes, both in previously untreated and heavily pre-treated B-CLL patients.

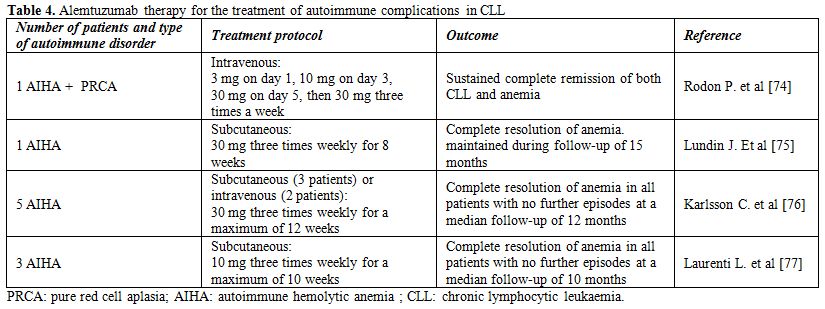

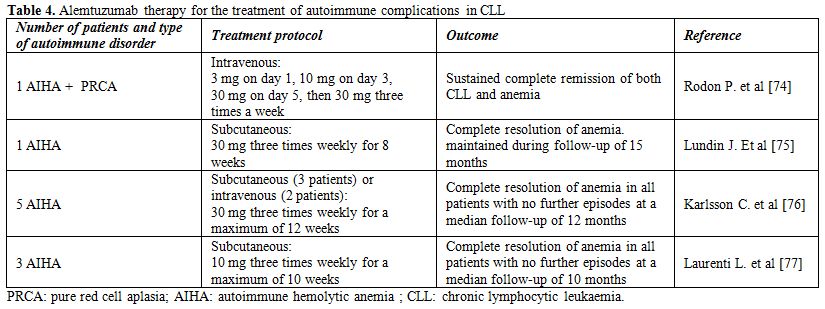

Alemtuzumab is active in advanced or refractory CLL[69-71] and has proven efficacy in patients with high-risk genetic markers such as deletion of chromosome 17p13 and p53 mutations.[72,73] The potent antitumor activity of alemtuzumab, in combination with its profound immunosuppressive activity, has prompted an investigation of its use in patients with severe and refractory CLL-related AIHA and ITP. However, the experience with Alemtuzumab in the treatment of CLL-related autoimmune disorders is rather limited, and only isolated cases and small series have been reported (Table 4).

Table 4. Alemtuzumab therapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

The first case of CLL-related autoimmune disease treated with Alemtuzumab was reported by Rodon et al.[74] The patient had life-threatening corticosteroid-resistant AIHA and PRCA. Following Alemtuzumab treatment he obtained a complete remission of both CLL and anemia, but died of recurrent sepsis and cachexia 10 months after completing the treatment. Another case of CLL and fludarabine-related refractory AIHA that was treated successfully with alemtuzumab was reported by Lundin et al..[75] The anemia was totally reversed, and hemoglobin level remained at 14 g/dL after 15 mo of unmaintained follow-up. In this patient, no infectious complications were noted either during or after alemtuzumab therapy.

Subsequently, Karlsson et al. described 5 CLL patients in an advanced stage with severe transfusion-dependent AIHA refractory to conventional therapy, including corticosteroids, rituximab and splenectomy, that were treated with subcutaneous (SC) or intravenous (IV) alemtuzumab at a dose of 30 mg three times weekly for a maximum of 12 weeks.[76] After a median time of 5 weeks (range 4-7), all patients responded with a marked rise in hemoglobin (Hb) concentration: the mean Hb increased from 7.2 g/dl at baseline to 11.9 g/dl at the end of treatment. All patients remained stable and without further AIHA episodes after a median follow-up time of 12 months. Treatment was relatively well tolerated, although grade 4 neutropenia occurred in two patients and cytomegalovirus reactivation in one.

The previous findings were further corroborated in our series of three patients with progressive CLL and AIHA that were treated with intravenous low-dose alemtuzumab (10 mg three times weekly for 10 weeks).[77] The total dose of alemtuzumab in our series was substantially lower than in the series of Karlsson et al (300 mg vs 880 mg, respectively). All three patients responded to alemtuzumab treatment with a >2 g/dl rise in Hb concentration. The duration of response was similar to the duration of response in the series of Karlsson et al. (10 vs 12 months), but longer treatment was required to achieve response (median 8 vs 5 weeks, respectively). Regarding CLL responses, a partial response was achieved in two and stable disease in one patient. Altogether, these data show that alemtuzumab displays considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complications in patients with CLL.

Ofatumumab and other Monoclonal Antibodies. Ofatumumab (HuMax-CD20; Arzerra, GlaxoSmithKline/Genmab) is a recently approved fully human type I anti-CD20 IgG1k mAb.[78,79] Ofatumumab induces killing of normal and malignant B cells via activation of complement and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.[79,80] Ofatumumab displays activity similar to rituximab with respect to antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) but has greater complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and a prolonged and more stable CD20 binding.[80] It appears to bind a different epitope of CD20 than rituximab.[81] As expected, the main ofatumumab toxicity observed in nonclinical studies was the severe and prolonged depletion of B lymphocytes both in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs.

A phase I/II study of ofatumumab at doses of 2000 mg in 33 relapsed/refractory CLL patients demonstrated an overall response rate of 50%.[82] Similar efficacy was reported in a larger trial which enrolled 138 patients with CLL refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab or CLL with bulky lymphadenopathy: the ORR was 58% for patients with refractory CLL and 47% for patients with bulky lymphadenopathy.

Ofatumumab is approved in the US for the treatment of patients with CLL who are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab.[78] However, no data have been reported in the literature regarding the use of ofatumumab in CLL-related autoimmune cytopenias. In addition, several other monoclonal antibodies are currently investigated in CLL, including the anti-CD20 antibody GA-101, the ant-CD23 antibody Lumiliximab, the anti-CD37 antibody TRU-016, the anti-CD22 antibody Epratuzumab and the anti-CD80 antibody Galiximab. The activity of these antibodies in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune cytopenias should also be investigated in future studies.

Autoimmunity is more common in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders than in patients with myeloproliferative conditions (8% vs. 1.7%, respectively).[1] Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by an association with autoimmune phenomena that are stronger than in other chronic lymphoproliferative disorders.[2-7]

Epidemiological data show that the occurrence of autoimmune cytopenia during the clinical history of CLL ranges from 4.3% to 9.7%.[8-12] The most common CLL-related immune haematological disturbance is autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA), which occurs in approximately 7% of the cases.[8-10,13] An additional proportion of patients (7-14%) may have a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) without clinical evidence of haemolysis.[12] Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and autoimmune granulocytopenia are more rare than AIHA, with an estimated frequency respectively of 1-5%.[8-9,13-14] and about 1%.[15] The incidence of immune disorders involving components of the blood coagulation system, such as acquired haemophilia or acquired von Willebrand disease has not been evaluated.

Regarding the association between CLL and non-haematological autoimmune disorders, data in the literature report that the proportion of patients with clinically apparent autoimmune disease ranges from 2% to 12% while the presence of serological markers of autoimmunity ranges from 8% to 41%.[16-18] However, no significant association was observed between CLL and non-haematological autoimmune diseases in case-control studies.[4] The mechanisms responsible for the development of immune cytopenias in CLL are only partially understood:

1) CLL cells may process red blood cell antigens and act as antigen presenting cells, inducing a T-cell response and the formation of polyclonal antibodies by normal B-cell, thus indirectly provoking autoimmune haemolytic anaemia;

2) CLL cells express inhibitory cytokines which alter tolerance, facilitating the escape of self-reactive cells;

3) rarely CLL cells are effector cells, directly producing a pathological monoclonal autoantibody;

4) CLL cells may be stimulated through their polyreactive BCR which recognizes auto-antigens.[4-6]

An increased risk to develop autoimmune cytopenia has been observed in patients displaying various adverse clinical or biological prognostic features, such as advanced stage,[4,9,16,19] older age,[8,12,16] high white cell count,[8,14,17] short lymphocyte doubling time,[10,16] increased beta-2-microglobulin levels,[10,12,17] CD38[10,17] and ZAP-70 positivity,[9,14] unmutated IGVH genes and stereotyped BCRs[20-22] band poor risk cytogenetics.[9,22]

Recent data of a retrospective series of 585 CLL patients indicated that unmutated IGHV status and/or unfavorable cytogenetic lesions (del17p13 and del11q23) were significantly associated with the risk of developing secondary AIHA (p<0.0001), also suggesting a possible role of specific stereotyped B-cell receptor subsets in a proportion of cases. Stereotyped HCDR3 sequences were identified in 29.6% of cases and were similarly represented among patients developing or not AIHA; notably, a particular subset (IGHV1-69 and IGHV4-30/IGHD2-2/IGHJ6) was associated with a significantly higher risk of AIHA than the other patients (p=0.004). Multivariate analysis showed that unmutated IGHV, del17p13 and del11q23, but not this stereotyped subset, were the strongest independent variables associated with AIHA.[22]

To clarify the importance of stage and therapy for the development of autoimmune complications, the GIMEMA Group (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto) conducted a study on 194 CLL cases with autoimmune complications and 434 CLL controls:[23] AIHA (129 cases) and ITP (35 cases) were typically present in patients multi-treated and/or in advanced stage. Age over the median (>69 years), stage C, and first and second line therapy were identified as an independent risk factors by multivariate analysis. The majority of patients with AIHA were in stage C, whereas cases of ITP were equally distributed across all 3 Binet stages. Both AIHA and ITP were almost exclusively observed in patients who had received first or second line therapy for CLL. In contrast, non-hematologic autoimmune complications and the presence of serological markers of autoimmunity were mostly observed in patients with early stage CLL (stage A in 17/23 cases), suggesting that different pathogenic mechanisms underlay hematologic and non-hematologic autoimmune phenomena in CLL.

The association between treatment and development of autoimmune cytopenias, particularly AIHA, was described many years ago,[24,2,3] it was mainly observed in patients treated with the purine analogs fludarabine, cladribine and pentostatin. [25-29] However, the risk of developing autoimmune cytopenia after exposure to multi-drug regimens containing purine analogues, such as fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab, is not greater than with other agents.[10,12,30,31] An intriguing finding emerged from the UK CLL4 trial: the incidence of AIHA was significantly lower in patients treated with fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (5%) than in those allocated to receive chlorambucil (12%) or fludarabine alone (11%)(p<0.01). That suggests a possible “protective” effect of the addition of cyclophosphamide on the onset of AIHA.[12] More recent data, coming from the German CLL 8 trial, showed that the rate of AIHA in CLL patients treated with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, with or without rituximab, was only 1%.[31]

Another crucial question is if the autoimmune cytopenias confer poor prognosis in CLL. In the study of Zent et al., survival of patients with autoimmune cytopenias diagnosed within 1 year of the diagnosis of CLL was similar to survival of patients without CLL-related cytopenia (median 9.3 vs. 9.7 years, P=0.881), suggesting that cytopenia caused by autoimmune disease is not an adverse prognostic factor. In contrast, survival of patients with cytopenia due to bone marrow failure was significantly shorter (median 4.4 years, P<0.001), demonstrating the need for accurate determination of the etiology of cytopenia in the prognostic classification of patients with CLL.[9]

Treatment

The choice of treatment for autoimmune cytopenias in patients with CLL depends on whether the underlying disease also requires treatment.[32] Patients with not-progressive CLL and autoimmune cytopenia not requiring treatment for the malignant disease are usually managed in the same manner as patients with a primary autoimmune cytopenia. In contrast, CLL patients with progressive disease requiring treatment for both the underlying disease and the autoimmune cytopenia have more “complex” treatment, requiring systemic chemo-immunotherapy.[33] Most patients with AIHA are symptomatic and require therapeutic intervention; although most leukemic patients with ITP are asymptomatic and the thrombocytopenia is detected on a routine blood count,[34] they are at higher risk of bleeding than patients with the sole ITP, being frequently older. Thus, it has been recommended to initiate therapy in patients with a platelet count below 30 x 109/l also asymptomatic.[35] Patients with autoimmune cytopenia in the absence of progressive CLL should be treated with conventional therapy, i.e. oral prednisone at a daily dose of 0,5–2 mg/kg. Prednisone is tapered once a response is observed over several months; pulsed high dose dexamethasone (40 mg/d) has been also recommended in 4-day pulses every 2 weeks.[36] Up to 80% of patients will respond to corticosteroids, but many responders will remain corticosteroid-dependent.[8,9,19] Patients, who do not respond after 4–6 weeks of therapy, are unlikely to respond. They should be considered for alternative immunosuppression (e.g. cyclosporine, mycophenolate or azathioprine) or, as discussed below, splenectomy, monoclonal antibodies or other biological agents.[37,38] Intravenous immunoglobulins can be useful when a rapid response is required, e.g. in patients with ITP and significant bleeding, prior to splenectomy or in cases of fulminant haemolysis. However, they will not give a lasting effect as a single agent. The role of splenectomy is better established in ITP than in AIHA. Although in one small series, splenectomy was found to be less effective and associated with greater morbidity in AIHA patients with systemic disease, including CLL, than in patients with idiopathic AIHA.[39] A more recent study showed a high rate (67%) of complete and durable responses in CLL patients treated with laparoscopic splenectomy.[40]

The role of the new thrombopoietin analogues romiplostim and eltrombopag in the treatment of ITP is still controversial. These agents increase platelet production rather than preventing their premature destruction.[41] The treatment should be taken indefinitely to maintain response, and their long-terms effects are largely unknown: among them, there is the marrow fibrosis. Both drugs have been demonstrated to be efficacious in resistant ITP patients after splenectomy failure and in those patients resistant, who are not surgical candidates.[42-44] Romiplostim and eltrombopag have been only occasionally reported in CLL-associated ITP treatment.[45-48] Clearly, the splenectomy in CLL-related ITP seems to have a wider role. Recently, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target normal and malignant B cells, such as rituximab and alemtuzumab, have become part of the standard treatment of CLL and are showing considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complications (Table 1).

Table 1. Monoclonal antibodies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Monoclonal Antibodies

Rituximab. Rituximab (Rituxan, Biogen IDEC, Cambridge, MA, and Mabthera, Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) is one of the first approved chimeric murine/human monoclonal IgG1 antibodies. Rituximab binds to the CD20 antigen, which is expressed on almost all B cells, and eliminates B cells through several mechanisms, including complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and induction of ‘direct cell death’ by growth inhibition and non-classic apoptosis.[49-51] mRituximab is considered to be well tolerated, nevertheless the most notable side effect is the infusion-related reaction, generally mild to moderate in severity. CLL patients with a markedly increased number of circulating lymphocytes present an increased risk of more serious adverse events, including respiratory insufficiency, tumour lysis syndrome and a rapid tumor clearance syndrome. Immunotherapy is frequently associated with grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and leucopenia while other side-effects, including severe infections, were not increased.

Rituximab represents one of the more active therapies for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL that do not respond to initial corticosteroid treatment (Tables 2-3). The first experience with this antibody in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune diseases was in two patients with pure red cell aplasia; both responded dramatically to rituximab treatment and became transfusion independent.[52] Subsequently, Gupta et al treated eight CLL patients with corticosteroid refractory AIHA with a combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (RCD). Cycles were repeated every 4 weeks until the best response. All eight patients achieved a remission of their AIHA and five became Coombs negative. Median duration of response was 13 months. RCD was also effective in achieving a response in patients that subsequently relapsed. [53]

Table 2. Rituximab monotherapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

Table 3. Rituximab combination therapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

Zaja et al. showed that rituximab given at the dose of 375 mg/m2 per week for 4 weeks is active in various CLL-associated autoimmune diseases that are refractory to standard immunosuppressive therapies.[54] They treated 7 patients with CLL-associated symptomatic autoimmune diseases, including four patients with warm AIHA, one patient with cold agglutinin disease (CAD), one patient with ITP, and one patient with axonal degenerating neuropathy (ADN). One of the AIHA patients and the patient with CAD achieved complete normalization of hemoglobin levels and laboratory signs of haemolysis, with response durations of 8+ and 38+ months, respectively. In the patient with ITP, complete remission was reached after the first week of treatment and the duration of response was 6 months. The patient with ADN achieved a marked neurological improvement after rituximab therapy, with response duration of 12 months.

D’Arena et al. investigated single agent rituximab in 14 patients with CLL-associated AIHA that failed first-line corticosteroid treatment.[55] Rituximab was given at a dose of 375 mg/m2/weekly for 4 weeks. A complete response was observed in 22% and a partial response in 50% of the cases. After a mean follow-up of 17 months, 8 patients were still alive, 6 of them transfusion-independent.

Hegde et al. showed that rituximab is active in CLL patients with refractory fludarabine-associated ITP.[56] Three patients who developed ITP while receiving fludarabine and who did not respond to treatment with corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) were treated with weekly rituximab (375 mg/m2 per week for 4 weeks). All patients had rapid and dramatic improvements in their platelet counts, and the response durations were 6 months or greater for all 3 patients.

In a retrospective analysis of 21 patients, D'Arena et al. showed that rituximab as a single agent (375 mg/m2/weekly for four cycles) is effective and well-tolerated treatment for CLL-related ITP refractory to corticosteroid therapy.[57] The overall response rate was 86% (57% CR, 29% PR), with a mean duration of response of 21 months. At a mean follow-up of 28 months, 66% of patients were still alive, 48% of them in CR and 14% in PR.

Recently, immunochemotherapy regimens, such as RCD or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristin and prednisone (R-CVP), have been regaining attention in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune diseases, as they can provide both anti-leukemic and anti-autoimmune effects in the absence of significant myelosuppression.[58-61] (Table 3) In the study of Kaufman et al.,[18] CLL patients with AIHA, one with ITP and two with both autoimmune diseases were treated with the RCD regimen. All CLL patients with AIHA responded to treatment with a median increase in hemoglobin of 5.2 g/dL and a median duration of response of 22 months. Nine relapsed patients responded, as well. Fifty percent of evaluable patients converted to Coombs negative, with a median duration of response of 41 months vs. 10 months for those who did not convert. All 3 patients affected with corticosteroid-refractory ITP also responded to RCD treatment.[60] Rossignol et al. reported the experience of three French university hospitals in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune disorders with the RCD protocol.[58] The study included 48 patients, among which 26 with AIHA, 9 with ITP, 8 with Evan's syndrome and 5 with PRCA, that had relapsed after previous treatment with corticosteroids, splenectomy, rituximab or alemtuzumab. The overall response rate was 89.5%, but relapses occurred in 19 patients (39.6%). The duration of response (median 24 months) was longer in patients presenting with autoimmune disease early during the course of CLL (<3 years), and in patients with PRCA and AIHA. The time to CLL progression (median of 16 months) was statistically shorter for patients with Evan's syndrome and ITP patients.

Bowen et al. treated 20 patients with progressive CLL and autoimmune cytopenia using the R-CVP protocol. A response to treatment with respect to the autoimmune cytopenia was observed in 19 patients (14 CR and 5 PR) with a median time to next treatment (TTT) for autoimmune cytopenia of 21.7 months. The progressive CLL responded in 17 patients (9 CR, 8 PR) with a median TTT of 27.7 months.[61] Grade 3-4 toxicities were infrequent and included infections (n = 3) and drug-induced pneumonitis (n = 1). Altogether, these data suggest that R-CVP is an effective and tolerable regimen for patients with autoimmune cytopenia and progressive CLL.

Alemtuzumab. The monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) is a recombinant humanized IgG1 k mAb targeting the CD52 antigen, which is expressed on normal and malignant human B and T lymphocytes, as well as natural killer cells, monocytes and macrophages.[62,63] The mechanism of action of alemtuzumab includes complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity[64] and possibly direct cytotoxicity, which has been observed in some,[65,66] but not all studies investigating this issue.[67,68]

Haematological and non-haematological toxicities such as neutropenia, lymphopenia and reactivation of herpes viruses infections, especially cytomegalovirus, are frequent after alemtuzumab therapy. Despite pre-medication with acetaminophen and diphenhydramine, intravenous administration is associated with adverse infusion reactions in 90% of patients, often severe; fever has been noted in 85% of patients frequently coupled with nausea, vomiting and rash. Considering the high risk of adverse infusion events when administered intravenously and the comparable biological activity of subcutaneous alemtuzumab associated to a decreased number of infusion reactions, subcutaneously route of administration has progressively increased.

Immunological recovery after alemtuzumab therapy showed a constant long lasting immune depletion with reduced counts of all lymphoid subsets, especially CD4+ lymphocytes, both in previously untreated and heavily pre-treated B-CLL patients.

Alemtuzumab is active in advanced or refractory CLL[69-71] and has proven efficacy in patients with high-risk genetic markers such as deletion of chromosome 17p13 and p53 mutations.[72,73] The potent antitumor activity of alemtuzumab, in combination with its profound immunosuppressive activity, has prompted an investigation of its use in patients with severe and refractory CLL-related AIHA and ITP. However, the experience with Alemtuzumab in the treatment of CLL-related autoimmune disorders is rather limited, and only isolated cases and small series have been reported (Table 4).

Table 4. Alemtuzumab therapy for the treatment of autoimmune complications in CLL

The first case of CLL-related autoimmune disease treated with Alemtuzumab was reported by Rodon et al.[74] The patient had life-threatening corticosteroid-resistant AIHA and PRCA. Following Alemtuzumab treatment he obtained a complete remission of both CLL and anemia, but died of recurrent sepsis and cachexia 10 months after completing the treatment. Another case of CLL and fludarabine-related refractory AIHA that was treated successfully with alemtuzumab was reported by Lundin et al..[75] The anemia was totally reversed, and hemoglobin level remained at 14 g/dL after 15 mo of unmaintained follow-up. In this patient, no infectious complications were noted either during or after alemtuzumab therapy.

Subsequently, Karlsson et al. described 5 CLL patients in an advanced stage with severe transfusion-dependent AIHA refractory to conventional therapy, including corticosteroids, rituximab and splenectomy, that were treated with subcutaneous (SC) or intravenous (IV) alemtuzumab at a dose of 30 mg three times weekly for a maximum of 12 weeks.[76] After a median time of 5 weeks (range 4-7), all patients responded with a marked rise in hemoglobin (Hb) concentration: the mean Hb increased from 7.2 g/dl at baseline to 11.9 g/dl at the end of treatment. All patients remained stable and without further AIHA episodes after a median follow-up time of 12 months. Treatment was relatively well tolerated, although grade 4 neutropenia occurred in two patients and cytomegalovirus reactivation in one.

The previous findings were further corroborated in our series of three patients with progressive CLL and AIHA that were treated with intravenous low-dose alemtuzumab (10 mg three times weekly for 10 weeks).[77] The total dose of alemtuzumab in our series was substantially lower than in the series of Karlsson et al (300 mg vs 880 mg, respectively). All three patients responded to alemtuzumab treatment with a >2 g/dl rise in Hb concentration. The duration of response was similar to the duration of response in the series of Karlsson et al. (10 vs 12 months), but longer treatment was required to achieve response (median 8 vs 5 weeks, respectively). Regarding CLL responses, a partial response was achieved in two and stable disease in one patient. Altogether, these data show that alemtuzumab displays considerable activity against both the malignant disease and the autoimmune complications in patients with CLL.

Ofatumumab and other Monoclonal Antibodies. Ofatumumab (HuMax-CD20; Arzerra, GlaxoSmithKline/Genmab) is a recently approved fully human type I anti-CD20 IgG1k mAb.[78,79] Ofatumumab induces killing of normal and malignant B cells via activation of complement and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.[79,80] Ofatumumab displays activity similar to rituximab with respect to antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) but has greater complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and a prolonged and more stable CD20 binding.[80] It appears to bind a different epitope of CD20 than rituximab.[81] As expected, the main ofatumumab toxicity observed in nonclinical studies was the severe and prolonged depletion of B lymphocytes both in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs.

A phase I/II study of ofatumumab at doses of 2000 mg in 33 relapsed/refractory CLL patients demonstrated an overall response rate of 50%.[82] Similar efficacy was reported in a larger trial which enrolled 138 patients with CLL refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab or CLL with bulky lymphadenopathy: the ORR was 58% for patients with refractory CLL and 47% for patients with bulky lymphadenopathy.

Ofatumumab is approved in the US for the treatment of patients with CLL who are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab.[78] However, no data have been reported in the literature regarding the use of ofatumumab in CLL-related autoimmune cytopenias. In addition, several other monoclonal antibodies are currently investigated in CLL, including the anti-CD20 antibody GA-101, the ant-CD23 antibody Lumiliximab, the anti-CD37 antibody TRU-016, the anti-CD22 antibody Epratuzumab and the anti-CD80 antibody Galiximab. The activity of these antibodies in the treatment of CLL-associated autoimmune cytopenias should also be investigated in future studies.

References

- Dührsen U, Augener W, Zwingers T, et al.

Spectrum and frequency of autoimmune derangements in

lymphoproliferative disorders: analysis of 637 cases and comparison

with myeloproliferative diseases. Br J Haematol. 1987; 67: 235-9.

- Galton DA. The pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1966; 94: 1005-10.

- Dameshek W. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia -

an accumulative disease of immunologically incompetent lymphocytes.

Blood. 1967; 29: 566-84.

- Hamblin TJ, Oscier DG, Young BJ.

Autoimmunity in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Journal of Clinical

Pathology. 1986; 39: 713-716.

- Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Autoantibodies in

chronic lymphocytic leukemia and related systemic autoimmune diseases.

Blood. 1993; 81: 2475-2487.

- Chiorazzi N, Rai KR, Ferrarini M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005; 352: 804-815.

- Zent CS, Kay NE. Autoimmune Complications

in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL). Best Practice & Research

Clinical Haematology. 2010; 23: 47-59.

- Mauro FR, Foa R, Cerretti R, et al.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical,

therapeutic, and prognostic features. Blood. 2000; 95:2786-92. PMid:10779422

- Zent CS, Ding W, Schwager SM, et al. The

prognostic significance of cytopenia in chronic lymphocytic

leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008; 141: 615-21.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07086.x PMid:18373706 PMCid:2675611

- Moreno C, Hodgson K, Ferrer G, et al.

Autoimmune cytopenias in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: prevalence,

clinical associations, and prognostic significance. Blood. 2010;116:

4771-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-05-286500 PMid:20736453

- Borthakur G, O'Brien S, Wierda WG, et al.

Immune anaemias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated

with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab-incidence and

predictors. Br J Haematol. 2007; 136 :800-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06513.x PMid:17341265

- Dearden C, Wade R, Else M, et al. The

prognostic significance of a positive direct antiglobulin test in

chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a beneficial effect of the combination of

fludarabine and cyclophosphamide on the incidence of hemolytic anemia.

Blood. 2008; 111: 1820-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-07-101303 PMid:18055869

- Dearden C. Disease-specific complications

of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ

Program. 2008: 450-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.450 PMid:19074125

- Visco C, Ruggeri M, Laura Evangelista M,

et al. Impact of immune thrombocytopenia on the clinical course of

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008; 111: 1110-1116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-09-111492 PMid:17986663

- Narra K, Borghaei H, Al-Saleem T, et al.

Pure red cell aplasia in B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder treated

with rituximab: report of two cases and review of the literature. Leuk

Res. 2006; 30: 109-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2005.05.017 PMid:16043218

- Barcellini W, Capalbo S, Agostinelli RM,

et al. Relationship between autoimmune phenomena and disease stage and

therapy in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2006;

91: 1689-92. PMid:17145607

- Duek A, Shvidel L, Braester A, et al.

Clinical and immunologic aspects of B chronic lymphocytic leukemia

associated with autoimmune disorders. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006; 8: 828-31.

PMid:17214095

- Vanura K, Le T, Esterbauer H, et al.

Autoimmune conditions and chronic infections in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia patients at diagnosis are associated with unmutated IgVH

genes. Haematologica. 2008; 93: 1912-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.12955 PMid:18838479

- Kyasa MJ, Parrish RS, Schichman SA, et al.

Autoimmune cytopenia does not predict poor prognosis in chronic

lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2003;

74: 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.10369 PMid:12949883

- Efremov DG, Ivanovski M, Siljanovski N,

Pozzato G, Cevreska L, Fais F, Chiorazzi N, Batista FD, Burrone OR.

Restricted immunoglobulin VH region repertoire in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood.

1996;87(9):3869-76. PMid:8611714

- Visco C, Maura F, Tuana G, Agnelli L,

Lionetti M, Fabris S, Novella E, Giaretta I, Reda G, Barcellini W,

Baldini L, Neri A, Rodeghiero F, Cortelezzi A. Immune thrombocytopenia

in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with

stereotyped B-cell receptors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(7):1870-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3019 PMid:22322667

- Maura F, Visco C, Falisi E, et al; B-cell

receptor configuration and adverse cytogenetics are associated with

autoimmune hemolytic anemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J

Hematol.2013;88:32-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23342 PMid:23115077

- Barcellini W, Capalbo S, Agostinelli RM,

et al; GIMEMA Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Group. Relationship between

autoimmune phenomena and disease stage and therapy in B-cell chronic

lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2006; 91:1689-92. PMid:17145607

- Lewis FB, Schwartz RS, Dameshek W. X

radiation and alkylating agents as possible –trigger- mechanisms in the

autoimmune complications of malignant lymphoproliferative disease. Clin

Exp Immunol. 1966;1: 3-11. PMid:5953036

- Bastion Y, Coiffier B, Dumontet C, et al.

Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia in two patients treated with

fludarabine for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Annals of Oncology.1992;

3: 171-172.

- Tosti S, Caruso R, D’Adamo F, et al.

Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with chronic

lymphocytic leukemia responsive to fludarabine-based treatment. Annals

of Hematology. 1992; 65: 238-239.

- Byrd JC, Hertler AA, Weiss RB, et al.

Fatal recurrence of autoimmune hemolytic anemia following pentostatin

therapy in a patient with a history of fludarabine-associated hemolytic

anemia. Annals of Oncology. 1995; 6: 300-301.

- Myint H, Copplestone JA, Orchard J, et al.

Fludarabine-related autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in patients with

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 1995;

91: 341-344.

- Weiss RB, Freiman J, Kweder SL, et al.

Hemolytic anemia after fludarabine therapy for chronic lymphocytic

leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16: 1885-1889. PMid:9586905

- Borthakur G, O'Brien S, Wierda WG, et al.

Immune anaemias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated

with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab - incidence and

predictors. Br J Haematol. 2007; 136:800-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06513.x

PMid:17341265

- Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et

al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in

patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010; 376: 1164-1174.

- Gribben JG. How I treat CLL up front. Blood. 2012;115:187-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-08-207126 PMid:19850738 PMCid:2941409

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al;

International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for

the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report

from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines.

Blood. 2008;111:5446-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906 PMid:18216293 PMCid:2972576

- Zent CS, Shanafelt T. Management of

autoimmune cytopenia complicating chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2009; 50: 863-864.

- Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, et al.

International consensus report on the investigation and management of

primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2010; 115: 168-186.

- Mazzucconi MG, Fazi P, Bernasconi S, et

al. Therapy with high-dose dexamethasone (HD-DXM) in previously

untreated patients affected by idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a

GIMEMA experience. Blood. 2007; 109: 1401-1407.

- D’Arena G, Cascavilla N. Chronic

lymphocytic leukemia-associated autoimmunehemolytic anemia. Leukemia

and Lymphoma. 2007; 48: 1072-1080.

- Lechner K, Jager U. How I treat autoimmune hemolytic anemias in adults. Blood. 2010; 116: 1831.

- Akpek G, McAneny D, Weintraub L.

Comparative response to splenectomy in Coombs-positive autoimmune

hemolytic anemia with or without associated disease. American Journal

of Hematology. 1999; 61: 98-102.

- Hill J, Walsh RM, McHam S, et al.

Laparoscopic splenectomy for autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients

with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case series and review of the

literature. American Journal of Hematology. 2004; 75:134-138.

- George JN. Management of immune

thrombocytopenia: something old, something new. New England Journal of

Medicine. 2010; 363: 1959-1961.

- Kuter DJ, Rummel M, Boccia R, et al.

Romiplostim or standard of care in patients with immune

thrombocytopenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010; 363: 1889-1899.

- Kuter DJ, Bussel JB, Lyons RM, et al.

Efficacy of romiplostim in patients with chronic immune

thrombocytopenic purpura: a double-blind randomised controlled trial.

Lancet. 2008; 371: 395-403.

- Bussel JB, Provan D, Shamsi T, et al.

Effect of eltrombopag on platelet counts and bleeding during treatment

of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a randomised,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 373: 641-648.

- Koehrer S, Keating MJ, Wierda WG.

Eltrombopag, a second-generation thrombopoietin receptor agonist, for

chronic lymphocytic leukemia-associated ITP. Leukemia. 2010; 24:

1096-1098.

- D’Arena G, Cascavilla N. Romiplostim for

chronic lymphocytic leukemia-associated immune thrombocytopenia.

Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2011; 52: 701-704.

- Sinisalo M, Sankelo M, Ita¨la-Remes M.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists can be used temporarily with patients

suffering from refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia-associated

immunologic thrombocytopenia. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2011; 52:

724-725.

- Tadmor T, Polliack A. Expanding the use of

thrombopoietin mimetic drugs: what about chronic lymphocytic leukemia?

Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2011; 52: 558-559.

- Teeling JL, Mackus WJ, Wiegman LJ, et al.

The biological activity of human CD20 monoclonal antibodies is linked

to unique epitopes on CD20. J Immunol. 2006; 177: 362-71. PMid:16785532

- Mossner E, Brunker P, Moser S, et al.

Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the

engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct

and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. 2010;

115: 4393-4402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979 PMid:20194898 PMCid:2881503

- Cartron G, Watier H, Golay J, et al. From

the bench to the bedside: ways to improve rituximab efficacy. Blood.

2004;104: 2635-2642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-03-1110 PMid:15226177

- Ghazal H. Successful treatment of pure red

cell aplasia with rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic

leukemia. Blood. 2002; 99:1092-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V99.3.1092 PMid:11807020

- Gupta N, Kavuru S, Patel D, et al.

Rituximab-based chemotherapy for steroid-refractory autoimmune

hemolytic anemia of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2002; 16:

2092-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2402676 PMid:12357362 PMid:20846302

- Zaja F, Vianelli N, Perotto A, et al.

Anti-CD20 therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia-associated

autoimmune diseases. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2003; 44: 1951-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1042819031000119235

- D’Arena G, Laurenti L, Capalbo S, et al.

Rituximab therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic leukemia-associated

autoimmune hemolytic anemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2006;

81:598-602.

- Hegde UP, Wilson WH, White T, et al.

Rituximab treatment of refractory fludarabine-associated immune

thrombocytopenia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002; 15; 100:

2260-2.

- D'Arena G, Capalbo S, Laurenti L, et al.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia-associated immune thrombocytopenia treated

with rituximab: a retrospective study of 21 patients. Eur J Haematol.

2010; 85: 502-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01527.x PMid: 20846302

- Rossignol J, Michallet AS, Oberic L, et

al. Rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone combination in the

management of autoimmune cytopenias associated with chronic lymphocytic

leukemia. Leukemia; 2011: 25: 473-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.278 PMid:21127498

- Michallet AS, Rossignol J, Cazin B, et al.

Rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone combination in management of

autoimmune cytopenias associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2011;52: 1401-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2011.591005

- Kaufman M, Limaye SA, Driscoll N, et al. A

combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone

effectively treats immune cytopenias of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2009; 50: 892-899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10428190902887563

- Bowen DA, Call TG, Shanafelt TD, et al.

Treatment of autoimmune cytopenia complicating progressive chronic

lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with rituximab,

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone. Leukemia and Lymphoma.

2010; 51: 620-627. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10428191003682767

- Carson KR, Focosi D, Major EO, et al.

Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal

leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab,

and efalizumab: a Review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and

Reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10: 816-824. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70161-5

- Robak T. Alemtuzumab for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008; 8: 1033-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14737140.8.7.1033

PMid:18588450

- Osterborg A, Foa R, Bezares RF, et al.

Management guidelines for the use of alemtuzumab in chronic lymphocytic

leukaemia. Leukemia. 2009; 23: 1980-1988.

- Mone AP, Cheney C, Banks AL, et al.

Alemtuzumab induces caspase-independent cell death in human chronic

lymphocytic leukemia cells through a lipid raft-dependent mechanism.

Leukemia. 2006; 20: 272-279.

- Smolewski P, Szmigielska-Kaplon A, Cebula

B, et al. Proapoptotic activity of alemtuzumab alone and in combination

with rituximab or purine nucleoside analogues in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2005; 46: 87-100.

- Stanglmaier M, Reis S, Hallek M. Rituximab

and alemtuzumab induce a nonclassic, caspase-independent apoptotic

pathway in B-lymphoid cell lines and in chronic lymphocytic leukemia

cells. Ann. Hematol. 2004; 83: 634-645.

- Zent CS, Chen JB, Kurten RC, et al.

Alemtuzumab (CAMPATH 1H) does not kill chronic lymphocytic leukemia

cells in serum free medium. Leuk. Res. 2004; 28: 495-507.

- Zent CS, Secreto CR, Laplant BR, et al.

Direct and complement dependent cytotoxicity in CLL cells from patients

with high-risk early-intermediate stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia

(CLL) treated with alemtuzumab and rituximab. Leuk. Res. 2008; 32:

1849-1856.

- Osterborg A, Dyer MJ, Bunjes D, et al.

Phase II multicenter study of human CD52 antibody in previously treated

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. European study group of CAMPATH-1H

treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997;

15:1567-74.

- Rai KR, Freter CE, Mercier RJ, et al.

Alemtuzumab in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients

who also had received fludarabine. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002; 20: 3891-7.

- Keating MJ, Flinn I, Jain V, et al.

Therapeutic role of alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in patients who have

failed fludarabine: results of a large international study. Blood.

2002; 99: 3554-61.

- Stilgenbauer S, Dohner H.

Campath-1H-induced complete remission of chronic lymphocytic leukemia

despite p53 gene mutation and resistance to chemotherapy. N. Engl. J.

Med. 2002; 347: 452-3.

- Rodon P, Breton P, Courouble G. Treatment

of pure red cell aplasia and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in chronic

lymphocytic leukaemia with Campath-1H.Eur J Haematol. 2003;70:319-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00055.x PMid:12694169

- Lundin J, Karlsson C, Celsing F.

Alemtuzumab therapy for severe autoimmune hemolysis in a patient with

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Oncol. 2006;23:137-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1385/MO:23:1:137

- Karlsson C, Hansson L, Celsing F, et al.

Treatment of severe refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia in B-cell

chronic lymphocytic leukemia with alemtuzumab (humanized CD52

monoclonal antibody).Leukemia. 2007;21:511-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404512 PMid:17215854

- Laurenti L, Tarnani M, Efremov DG, et al.

Efficacy and safety of low-dose alemtuzumab as treatment of autoimmune

hemolytic anemia in pretreated B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia. 2007; 21:1819-21 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404703 PMid:17443222

- Wierda WG, Kipps TJ, Mayer J, et al.

Ofatumumab as single-agent CD20 immunotherapy in fludarabine-refractory

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010; 28: 1749-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3187 PMid:20194866

- Sanford M, McCormack PL. Ofatumumab. Drugs. 2010; 70: 1013-1019. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/11203850-000000000-00000

PMid:20481657

- Beum PV, Lindorfer MA, Beurskens F, et al.

Complement activation on B lymphocytes opsonized with rituximab or

ofatumumab produces substantial changes in membrane structure preceding

cell lysis. J. Immunol. 2008; 181: 822-832. PMid:18566448

- Teeling JL, French RR, Cragg MS, et al.

Characterization of new human CD20 monoclonal antibodies with potent

cytolytic activity against non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2004; 104:

1793-1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-01-0039 PMid:15172969

- Robak T. Ofatumumab, a human monoclonal

antibody for lymphoid malignancies and autoimmune disorders. Curr.

Opin. Mol. Ther. 2008; 10: 294-309.

PMid:18535937