Management of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in the Elderly

Francesco Lo-Coco1,2, Roberto Latagliata3, Massimo Breccia3

1 Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, University Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

2 Laboratory of Neuro-Oncohematology, Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome, Italy

3 Department of Cellular Biotechnologies and Hematology, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

2 Laboratory of Neuro-Oncohematology, Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome, Italy

3 Department of Cellular Biotechnologies and Hematology, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

Correspondence

to: Francesco

Lo-Coco, MD. Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, Tor Vergata

University, Via Montpellier 1, 00133 Rome, Italy. E-mail: francesco.lo.coco@uniroma2.it

Published: June 8, 2013

Received: March 14, 2013

Accepted: June 6, 2013

Citation: Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2013, 5(1): e2013032, DOI: 10.4084/MJHID.2013.045

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open

Access article

distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Unlike other forms of AML, APL is

less frequently diagnosed in the elderly and has a relatively

favourable outcome. Elderly patients with APL seem at least as

responsive to therapy as do younger patients, but rates of response and

survival are lower in this age setting owing to a higher incidence of

early deaths and deaths in remission when conventional treatment with

ATRA and chemotherapy is used. Elderly APL patients are more likely to

present with low-risk features compared with younger patients, and this

may explain the relative low risk of relapse reported in several

clinical studies. Alternative approaches,

such as arsenic trioxide and gentuzumab

ozogamicin have been tested with success in this setting and could

replace in the near future frontline conventional chemotherapy and

ATRA.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a peculiar subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) associated with unique biologic features and requiring specific management. APL has become a well-recognized entity, by the French-American-British (FAB) identified as the M3 subtype, and by WHO classification, accounting for approximately 10% of cases of all AMLs.[1,2,3] Presenting features include a severe coagulopathy due to excessive fibrinolysis and a frequently low white blood cell (WBC) count, although 20% to 30% patients present with WBC counts higher than 10,000/μL; striking sensitivity to anthracycline-containing chemotherapy and finally a unique responsiveness to differentiation treatment with retinoids. [4,5]

A specific reciprocal translocation involving the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17 is the marker of the disease.[6] This chromosomal rearrangement involves the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) gene on the long arm of chromosome 17 and the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene on chromosome 15. Two fusion genes are generated as a consequence, i.e. PML/RARα and the reciprocal RARα/PML.[7, 8, 9] The median age at presentation is usually 40-45 years as reported in various clinical studies [10-14], whereas the incidence reported in patients aged from 60 to 70 years varies from 15 to 20% and for patients > 70 years from 1 to 6%. A population-based USA study reported an early death rate of 24% in patients aged 55 years or more[15], while in a Swedish Leukemia Registry study the early death rate was 29% in all age groups and 50% in patients aged over 60 years.[16] These percentages could be underestimated due to the fact that many older patients are excluded from clinical trials with intensive chemotherapy based on poor performance status. For this reason, outcome and clinical features at baseline in different clinical studies demonstrate a great variability. In this paper we review clinical results obtained in elderly APL patients with conventional chemotherapy and with more recent, alternative approaches.

Results With Frontline Therapy with ATRA and Chemotherapy.

Before the advent of ATRA, complete remission (CR) rates obtained in elderly APL with chemotherapy alone were in the range of 50%.[17-19] Several trials reported the efficacy of all trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy or concomitantly combined. The European APL group reported the results of the randomized APL 93 trial in which elderly patients (from 66 to 75 years) received ATRA followed by chemotherapy. CR in patients older than 60 years was high (86%) but significantly lower than that reported in younger patients (94%) and even in patients older than 70 years, the CR rate remained high (85%).14 The European APL group updated and reported separately the results of APL93 trial in elderly patients and confirmed the overall lower CR rate as compared to younger patients and a higher incidence of early death in this subset, although patients with higher WBC count (>10,000/μL) were not represented. The 4-year incidence of relapse was 15.6% in adults older than 60 and 23.2% in younger adults although most elderly patients received less intensive consolidation chemotherapy. However, 18.6% of the patients older than 60 years who entered remission died in CR, mainly from sepsis during consolidation course or maintenance treatment, as compared to 5.7% of younger adults. Therefore, 4-year OS was 57.8% in the elderly compared to 78% in younger patients.[20] The GIMEMA group treated 134 elderly patients (median age 66 years) with ATRA and idarubicin, reporting a CR rate of 86% and a death rate of 12% during induction. After achievement of CR, 67 patients received three consolidation courses, whereas 39 patients entered in an amended protocol and received only the first cycle: of the first series, 18 patients were withdrawn due to toxicity and 9 patients died in CR, whereas in the second series two patients died in CR. The results suggested that less intensive chemotherapy in the setting of elderly APL allows significant reduction of treatment-related toxicity maintaining therapeutic efficacy.[21] To reduce treatment-related toxicity in the elderly, the GIMEMA group started in 1997 an amended protocol for patients aged >60years, with the same induction (ATRA+idarubicin) as in younger patients, followed by a single consolidation course (idarubicin plus cytarabine) instead of 3, and by maintenance with intermittent ATRA. The trial enrolled 60 patients of whom 54 (90%) achieved haematological remission and six died during induction. Four additional patients died in CR from haemorrhage and infection prior or during consolidation therapy. Eleven patients relapsed at a median time of 17.5 months from CR. The 5-year OS, disease-free survival (DFS) and CIR rates were 68.5%, 64.6% and 27.4%, respectively. The results of the trial showed improved OS compared to original protocol (68.5% vs 56%) due to reduction of non-relapse mortality. CIR rate remained similar to that of previous trial in spite of reduced intensity of chemotherapy. The difference in maintenance therapy did not seem to influence the outcome between the original and the amended trial.[22] The Spanish PETHEMA group reported in 2004 their experience in patients aged > 60 years treated with ATRA plus idarubicin for induction, 3 anthracycline-based courses for consolidation followed by maintenance including ATRA. CR was achieved in 84% of patients, but 7 patients died in remission during consolidation and maintenance treatment. The group reported 6-year cumulative incidence of relapse, leukemia-free survival, and disease-free survival rates of 8.5%, 91%, and 79%, respectively. The authors reported in this series a higher incidence of low-risk patients as compared to younger patients, which in part may explain the low relapse rate observed.[23] The Japanese cooperative group JALSG compared the outcome of elderly patients with that of younger APL patients and confirmed a lower CR rate due to more early deaths. Forty-six patients (16.3%) out of 302 patients registered were described, median age 63 years. A comparison between younger and older patients did not reveal differences in terms of relapse risk at baseline (similar prevalence of high-risk) or other clinical features, except for lower platelet count, lower serum albumin and worse performance status in elderly patients. As reported by PETHEMA group [24], early deaths in the Japanese study were associated with low performance status at baseline and low albumin level. Cumulative incidence of relapse was similar between elderly and younger patients as reported also by the GIMEMA and the European APL group, but with 10-year OS was inferior (63% and 82% in older and younger patients, respectively).[25] The European APL Group also reported that 10 year-OS in elderly patients was lower than that of the whole population (58.1% vs 77%) and the major cause of death in their elderly patients was sepsis during myelosuppression. The German AML Cooperative Group registered 91 elderly APL patients since 1994 and recently reported the outcome in this subset. Sixty-eight patients were treated in clinical trials and 23 were non-eligible for intensive chemotherapy. Fifty-six patients received ATRA associated to TAD (6-thioguanine, cytarabine and daunorubicine) as induction therapy followed by consolidation and maintenance. Fourteen patients received an intensification therapy with HAM schedule (high-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone). The early death rate was 48% in non-eligible patients and 29% for patients enrolled in clinical trials, but approximately 30% of patients had high-risk features at baseline. Seven-year OS, EFS and relapse-free survival (RFS) were 45%, 40% and 48% in patients treated with TAD schedule whereas beneficial effect in terms of RFS was reported (83%) for patients who received intensification.[26]

Results with Arsenic Trioxide and Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin.

Arsenic trioxide (ATO) combined or not with ATRA has proven highly effective in APL and is known to carry considerably less toxicity as compared to conventional chemotherapy-based approaches. Given that chemotherapy-related toxicity is a major issue in elderly APL, ATO seems an attractive option for frontline therapy in this setting. Considering the absence of myelosuppressive effects during post-remission therapy, ATO treatment can therefore not only shorten the duration of hospitalization but also avoid deaths from infection and serious infectious complications in CR, therefore prolonging the survival time in the elderly patient.[27] The Chinese group reported the long-term outcome of 33 elderly patients (aged > 60 years, range 60-79, only 5 patients considered at high-risk at baseline) treated with ATO as single agent for up to 4 years. Eighty-eighth % of patients achieved CR and the most common adverse event was leukocytosis, developed in 64% of patients with serious differentiation syndrome being observed in only 5 cases. Twenty-eight patients proceeded to post-remission therapy: adverse effects during therapy were mild, and transient and none of the treated patients died from ATO-related toxicities. With a median follow-up of 99 months, the 10-year cumulative incidence of relapse, OS, DFS, and cause-specific survival were 10.3%, 69.3%, 64.8%, and 84.8%, respectively, which are comparable with those reported in the younger APL population.[28]

GO is a recombinant humanized immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody (hP67.6) conjugated to N-acetyl-gamma calicheamicin dimethyl hydrazide, a naturally potent antibiotic.[29] Several reasons account for the high efficacy of GO-based treatment in APL: the disease is characterized by a consistent phenotypic profile, with negative staining for HLA-DR and CD34 and strong expression of CD33; calicheamicin is a potent drug, similar to anthracyclines, which are known to be highly effective in APL; lack of, or very low expression in APL blasts of the Pgp 170.[30-33] In 2004, our group reported on the efficacy of GO as a single agent (at the dose of 6 mg/mq) in 16 APL patients who had relapsed at the molecular level: molecular remission was obtained in 9 out of 11 (91%) patients tested after 2 doses and in 13 of 13 patients (100%) tested after the third dose.[34] Our group also reported a preliminary experience in 3 unfit elderly APL patients treated for molecular relapse with GO at low dose (3 mg/m2).[35] The first patient was in third molecular relapse and was pre-treated with GO at 6 mg/m2 for first molecular relapse. He was retreated with 2 doses of GO and remained in complete remission for 10 months and finally died for reasons not correlated with the disease. The second patient, considered unfit for chemotherapy due to another concomitant neoplasia, received three courses of consolidation with GO and maintained a long-lasting molecular response. The third patient was considered not eligible for intensive chemotherapy due an antecedent cardiac ischemia: he received three cycles of GO obtaining complete molecular remission and remained in complete molecular remission after 14 months. Finizio et al reported the case of an elderly patient not eligible for intensive chemotherapy due to severe cardiac failure and chronic anticoagulant therapy. After an induction therapy with ATRA alone at standard dose for a prolonged time (80 days), the patient received GO at the dose of 6 mg/m2 monthly for two months as consolidation therapy and remained in molecular remission for 29 months.[36] Unfortunately, GO was withdrawn in 2010 after the results of randomized study by SWOG showing no improvement in efficacy and increased toxicity in the setting of elderly AML.

Treatment of Very Elderly Patients (> 70 years).

Disperati et al. reported 13 patients diagnosed between 1999 and 2006 with a median age of 78 years (range 71-87), treated with ATRA associated to chemotherapy (cytarabine plus daunorubicine). Ninety-two % of patients entered CR and received consolidation with two courses of chemotherapy and maintenance with ATRA for 9 months. The reported 2-year OS was 76% with 10% death rate in the post-remission phase.[37] Our group reported 12 patients aged > 70 years (median age 74.7 years) followed in a single center between 1991 and 2008. According to the Sanz’s relapse risk score, 7 patients were classified as low and 5 patients as intermediate risk. Eight patients received standard induction with ATRA and idarubicin whereas 4 patients received only ATRA, but during induction they needed the association of chemotherapy for severe leukocytosis. All patients achieved hematologic and molecular remission and differentiation syndrome occurred in 2 patients. All but one patient received consolidation (chemotherapy alone in 7 patients, chemotherapy plus ATRA in 3 patients and ATRA alone in 1 patient).[38] Four patients experienced disease relapse. Ferrara and colleagues reported 34 unselected elderly patients aged over 60 years (median age 70 years) treated for induction with ATRA plus chemotherapy or with ATRA alone. Of these, 23 (68%) fulfilled inclusion criteria of the AIDA protocol, whereas 11 (32%) received a personalized treatment. CR was reached in 68% of patients that were consolidated with the first cycle of the AIDA schedule (idarubicin plus cytarabine) or with gentuzumab ozogamicin. Median OS reported was 38 months and none of the patients died during post-remission phase.[39]

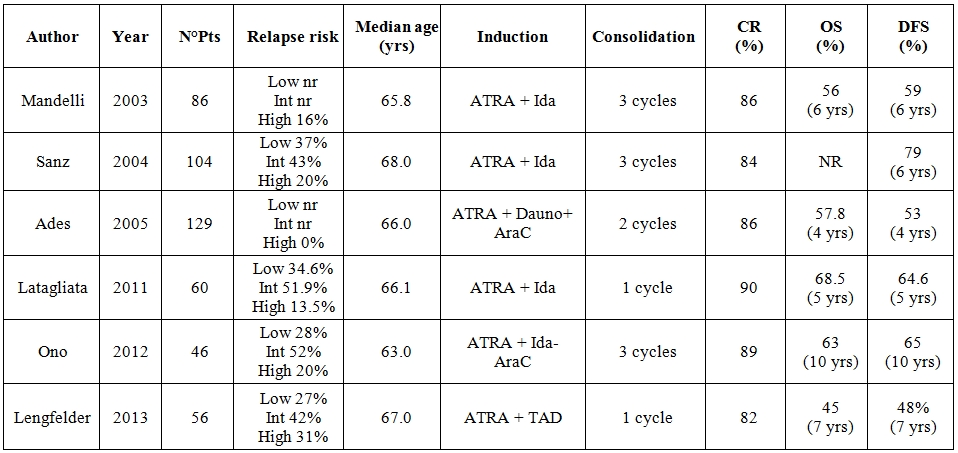

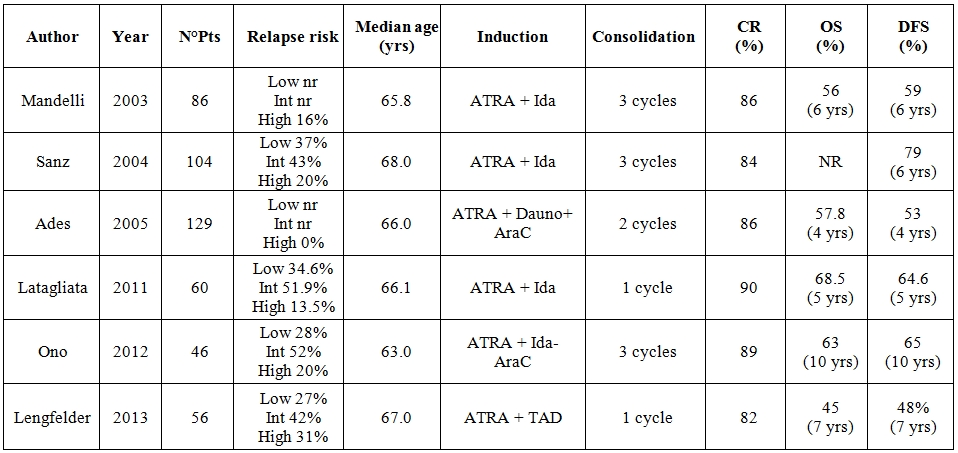

Table 1. Outcome results in main studies on elderly APL.

Legend: ATRA, All-trans retinoic acid. Ida, idarubicin. AraC, cytosine arabinoside. TAD, thioguanine, cytocine arabinoside, daunorubicin. CR, complete remission. OS, overall survival. DFS, disease-free survival. Nr= not reported.

Relapsed Patients.

ATRA combined with chemotherapy can yield second molecular CR in a large proportion of older relapsed APL patients, but this approach is associated with significant toxicity and profound myelosuppression.[40] Although only few experiences have been reported in the subset of elderly patients who relapse, ATO is reported to yield at least equivalent hematological and molecular results with limited toxicity. Soignet et al reported in 2001 the US multicenter experience and 8 out of 40 patients were aged over 60 years. Six of them (75%) achieved a CR as compared to 26/32 younger (81%) patients. OS in elderly patients was 38% at 18 months compared to 66% in the overall population, probably due to the fact that older patients did not receive transplant procedures after CR.[41] Recently we reported on the efficacy of prolonged therapy with combined ATO and ATRA in relapsed patients: 3 out of 9 patients were aged over 60 years and received 5 cycles of ATO and ATRA as reported by Estey et al [42]. Only 1 patient experienced electrolyte abnormalities during ATO administration, but none of the patients had other toxicities and all maintained prolonged molecular CR.[43]

Conclusions.

APL is relatively rare in elderly patients and ATRA combined with chemotherapy has considerably improved survival also in this setting. Compared to younger patients, however, outcome in elderly APL is inferior due to higher incidence of early death and of death in CR. Distinct to other AML subsets, relapses are quite uncommon in elderly APL patients, and the disease is curable in the majority of cases. However, it is likely that some high risk patient are excluded from entering clinical trials. For the frail patients who are considered unfit for conventional treatment, ATO with or without ATRA might be a reasonable alternative to the standard ATRA plus chemotherapy approach, although supporting scientific data currently are limited, particularly with respect to rates of remission and complications such as APL differentiation syndrome. It is foreseen that the ATO plus ATRA combination which very recently showed similar efficacy as compared to ATRA and chemotherapy in younger patients, will be explored in the near future in larger studies involving elderly patients.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a peculiar subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) associated with unique biologic features and requiring specific management. APL has become a well-recognized entity, by the French-American-British (FAB) identified as the M3 subtype, and by WHO classification, accounting for approximately 10% of cases of all AMLs.[1,2,3] Presenting features include a severe coagulopathy due to excessive fibrinolysis and a frequently low white blood cell (WBC) count, although 20% to 30% patients present with WBC counts higher than 10,000/μL; striking sensitivity to anthracycline-containing chemotherapy and finally a unique responsiveness to differentiation treatment with retinoids. [4,5]

A specific reciprocal translocation involving the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17 is the marker of the disease.[6] This chromosomal rearrangement involves the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) gene on the long arm of chromosome 17 and the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene on chromosome 15. Two fusion genes are generated as a consequence, i.e. PML/RARα and the reciprocal RARα/PML.[7, 8, 9] The median age at presentation is usually 40-45 years as reported in various clinical studies [10-14], whereas the incidence reported in patients aged from 60 to 70 years varies from 15 to 20% and for patients > 70 years from 1 to 6%. A population-based USA study reported an early death rate of 24% in patients aged 55 years or more[15], while in a Swedish Leukemia Registry study the early death rate was 29% in all age groups and 50% in patients aged over 60 years.[16] These percentages could be underestimated due to the fact that many older patients are excluded from clinical trials with intensive chemotherapy based on poor performance status. For this reason, outcome and clinical features at baseline in different clinical studies demonstrate a great variability. In this paper we review clinical results obtained in elderly APL patients with conventional chemotherapy and with more recent, alternative approaches.

Results With Frontline Therapy with ATRA and Chemotherapy.

Before the advent of ATRA, complete remission (CR) rates obtained in elderly APL with chemotherapy alone were in the range of 50%.[17-19] Several trials reported the efficacy of all trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy or concomitantly combined. The European APL group reported the results of the randomized APL 93 trial in which elderly patients (from 66 to 75 years) received ATRA followed by chemotherapy. CR in patients older than 60 years was high (86%) but significantly lower than that reported in younger patients (94%) and even in patients older than 70 years, the CR rate remained high (85%).14 The European APL group updated and reported separately the results of APL93 trial in elderly patients and confirmed the overall lower CR rate as compared to younger patients and a higher incidence of early death in this subset, although patients with higher WBC count (>10,000/μL) were not represented. The 4-year incidence of relapse was 15.6% in adults older than 60 and 23.2% in younger adults although most elderly patients received less intensive consolidation chemotherapy. However, 18.6% of the patients older than 60 years who entered remission died in CR, mainly from sepsis during consolidation course or maintenance treatment, as compared to 5.7% of younger adults. Therefore, 4-year OS was 57.8% in the elderly compared to 78% in younger patients.[20] The GIMEMA group treated 134 elderly patients (median age 66 years) with ATRA and idarubicin, reporting a CR rate of 86% and a death rate of 12% during induction. After achievement of CR, 67 patients received three consolidation courses, whereas 39 patients entered in an amended protocol and received only the first cycle: of the first series, 18 patients were withdrawn due to toxicity and 9 patients died in CR, whereas in the second series two patients died in CR. The results suggested that less intensive chemotherapy in the setting of elderly APL allows significant reduction of treatment-related toxicity maintaining therapeutic efficacy.[21] To reduce treatment-related toxicity in the elderly, the GIMEMA group started in 1997 an amended protocol for patients aged >60years, with the same induction (ATRA+idarubicin) as in younger patients, followed by a single consolidation course (idarubicin plus cytarabine) instead of 3, and by maintenance with intermittent ATRA. The trial enrolled 60 patients of whom 54 (90%) achieved haematological remission and six died during induction. Four additional patients died in CR from haemorrhage and infection prior or during consolidation therapy. Eleven patients relapsed at a median time of 17.5 months from CR. The 5-year OS, disease-free survival (DFS) and CIR rates were 68.5%, 64.6% and 27.4%, respectively. The results of the trial showed improved OS compared to original protocol (68.5% vs 56%) due to reduction of non-relapse mortality. CIR rate remained similar to that of previous trial in spite of reduced intensity of chemotherapy. The difference in maintenance therapy did not seem to influence the outcome between the original and the amended trial.[22] The Spanish PETHEMA group reported in 2004 their experience in patients aged > 60 years treated with ATRA plus idarubicin for induction, 3 anthracycline-based courses for consolidation followed by maintenance including ATRA. CR was achieved in 84% of patients, but 7 patients died in remission during consolidation and maintenance treatment. The group reported 6-year cumulative incidence of relapse, leukemia-free survival, and disease-free survival rates of 8.5%, 91%, and 79%, respectively. The authors reported in this series a higher incidence of low-risk patients as compared to younger patients, which in part may explain the low relapse rate observed.[23] The Japanese cooperative group JALSG compared the outcome of elderly patients with that of younger APL patients and confirmed a lower CR rate due to more early deaths. Forty-six patients (16.3%) out of 302 patients registered were described, median age 63 years. A comparison between younger and older patients did not reveal differences in terms of relapse risk at baseline (similar prevalence of high-risk) or other clinical features, except for lower platelet count, lower serum albumin and worse performance status in elderly patients. As reported by PETHEMA group [24], early deaths in the Japanese study were associated with low performance status at baseline and low albumin level. Cumulative incidence of relapse was similar between elderly and younger patients as reported also by the GIMEMA and the European APL group, but with 10-year OS was inferior (63% and 82% in older and younger patients, respectively).[25] The European APL Group also reported that 10 year-OS in elderly patients was lower than that of the whole population (58.1% vs 77%) and the major cause of death in their elderly patients was sepsis during myelosuppression. The German AML Cooperative Group registered 91 elderly APL patients since 1994 and recently reported the outcome in this subset. Sixty-eight patients were treated in clinical trials and 23 were non-eligible for intensive chemotherapy. Fifty-six patients received ATRA associated to TAD (6-thioguanine, cytarabine and daunorubicine) as induction therapy followed by consolidation and maintenance. Fourteen patients received an intensification therapy with HAM schedule (high-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone). The early death rate was 48% in non-eligible patients and 29% for patients enrolled in clinical trials, but approximately 30% of patients had high-risk features at baseline. Seven-year OS, EFS and relapse-free survival (RFS) were 45%, 40% and 48% in patients treated with TAD schedule whereas beneficial effect in terms of RFS was reported (83%) for patients who received intensification.[26]

Results with Arsenic Trioxide and Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin.

Arsenic trioxide (ATO) combined or not with ATRA has proven highly effective in APL and is known to carry considerably less toxicity as compared to conventional chemotherapy-based approaches. Given that chemotherapy-related toxicity is a major issue in elderly APL, ATO seems an attractive option for frontline therapy in this setting. Considering the absence of myelosuppressive effects during post-remission therapy, ATO treatment can therefore not only shorten the duration of hospitalization but also avoid deaths from infection and serious infectious complications in CR, therefore prolonging the survival time in the elderly patient.[27] The Chinese group reported the long-term outcome of 33 elderly patients (aged > 60 years, range 60-79, only 5 patients considered at high-risk at baseline) treated with ATO as single agent for up to 4 years. Eighty-eighth % of patients achieved CR and the most common adverse event was leukocytosis, developed in 64% of patients with serious differentiation syndrome being observed in only 5 cases. Twenty-eight patients proceeded to post-remission therapy: adverse effects during therapy were mild, and transient and none of the treated patients died from ATO-related toxicities. With a median follow-up of 99 months, the 10-year cumulative incidence of relapse, OS, DFS, and cause-specific survival were 10.3%, 69.3%, 64.8%, and 84.8%, respectively, which are comparable with those reported in the younger APL population.[28]

GO is a recombinant humanized immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody (hP67.6) conjugated to N-acetyl-gamma calicheamicin dimethyl hydrazide, a naturally potent antibiotic.[29] Several reasons account for the high efficacy of GO-based treatment in APL: the disease is characterized by a consistent phenotypic profile, with negative staining for HLA-DR and CD34 and strong expression of CD33; calicheamicin is a potent drug, similar to anthracyclines, which are known to be highly effective in APL; lack of, or very low expression in APL blasts of the Pgp 170.[30-33] In 2004, our group reported on the efficacy of GO as a single agent (at the dose of 6 mg/mq) in 16 APL patients who had relapsed at the molecular level: molecular remission was obtained in 9 out of 11 (91%) patients tested after 2 doses and in 13 of 13 patients (100%) tested after the third dose.[34] Our group also reported a preliminary experience in 3 unfit elderly APL patients treated for molecular relapse with GO at low dose (3 mg/m2).[35] The first patient was in third molecular relapse and was pre-treated with GO at 6 mg/m2 for first molecular relapse. He was retreated with 2 doses of GO and remained in complete remission for 10 months and finally died for reasons not correlated with the disease. The second patient, considered unfit for chemotherapy due to another concomitant neoplasia, received three courses of consolidation with GO and maintained a long-lasting molecular response. The third patient was considered not eligible for intensive chemotherapy due an antecedent cardiac ischemia: he received three cycles of GO obtaining complete molecular remission and remained in complete molecular remission after 14 months. Finizio et al reported the case of an elderly patient not eligible for intensive chemotherapy due to severe cardiac failure and chronic anticoagulant therapy. After an induction therapy with ATRA alone at standard dose for a prolonged time (80 days), the patient received GO at the dose of 6 mg/m2 monthly for two months as consolidation therapy and remained in molecular remission for 29 months.[36] Unfortunately, GO was withdrawn in 2010 after the results of randomized study by SWOG showing no improvement in efficacy and increased toxicity in the setting of elderly AML.

Treatment of Very Elderly Patients (> 70 years).

Disperati et al. reported 13 patients diagnosed between 1999 and 2006 with a median age of 78 years (range 71-87), treated with ATRA associated to chemotherapy (cytarabine plus daunorubicine). Ninety-two % of patients entered CR and received consolidation with two courses of chemotherapy and maintenance with ATRA for 9 months. The reported 2-year OS was 76% with 10% death rate in the post-remission phase.[37] Our group reported 12 patients aged > 70 years (median age 74.7 years) followed in a single center between 1991 and 2008. According to the Sanz’s relapse risk score, 7 patients were classified as low and 5 patients as intermediate risk. Eight patients received standard induction with ATRA and idarubicin whereas 4 patients received only ATRA, but during induction they needed the association of chemotherapy for severe leukocytosis. All patients achieved hematologic and molecular remission and differentiation syndrome occurred in 2 patients. All but one patient received consolidation (chemotherapy alone in 7 patients, chemotherapy plus ATRA in 3 patients and ATRA alone in 1 patient).[38] Four patients experienced disease relapse. Ferrara and colleagues reported 34 unselected elderly patients aged over 60 years (median age 70 years) treated for induction with ATRA plus chemotherapy or with ATRA alone. Of these, 23 (68%) fulfilled inclusion criteria of the AIDA protocol, whereas 11 (32%) received a personalized treatment. CR was reached in 68% of patients that were consolidated with the first cycle of the AIDA schedule (idarubicin plus cytarabine) or with gentuzumab ozogamicin. Median OS reported was 38 months and none of the patients died during post-remission phase.[39]

Table 1. Outcome results in main studies on elderly APL.

Legend: ATRA, All-trans retinoic acid. Ida, idarubicin. AraC, cytosine arabinoside. TAD, thioguanine, cytocine arabinoside, daunorubicin. CR, complete remission. OS, overall survival. DFS, disease-free survival. Nr= not reported.

Relapsed Patients.

ATRA combined with chemotherapy can yield second molecular CR in a large proportion of older relapsed APL patients, but this approach is associated with significant toxicity and profound myelosuppression.[40] Although only few experiences have been reported in the subset of elderly patients who relapse, ATO is reported to yield at least equivalent hematological and molecular results with limited toxicity. Soignet et al reported in 2001 the US multicenter experience and 8 out of 40 patients were aged over 60 years. Six of them (75%) achieved a CR as compared to 26/32 younger (81%) patients. OS in elderly patients was 38% at 18 months compared to 66% in the overall population, probably due to the fact that older patients did not receive transplant procedures after CR.[41] Recently we reported on the efficacy of prolonged therapy with combined ATO and ATRA in relapsed patients: 3 out of 9 patients were aged over 60 years and received 5 cycles of ATO and ATRA as reported by Estey et al [42]. Only 1 patient experienced electrolyte abnormalities during ATO administration, but none of the patients had other toxicities and all maintained prolonged molecular CR.[43]

Conclusions.

APL is relatively rare in elderly patients and ATRA combined with chemotherapy has considerably improved survival also in this setting. Compared to younger patients, however, outcome in elderly APL is inferior due to higher incidence of early death and of death in CR. Distinct to other AML subsets, relapses are quite uncommon in elderly APL patients, and the disease is curable in the majority of cases. However, it is likely that some high risk patient are excluded from entering clinical trials. For the frail patients who are considered unfit for conventional treatment, ATO with or without ATRA might be a reasonable alternative to the standard ATRA plus chemotherapy approach, although supporting scientific data currently are limited, particularly with respect to rates of remission and complications such as APL differentiation syndrome. It is foreseen that the ATO plus ATRA combination which very recently showed similar efficacy as compared to ATRA and chemotherapy in younger patients, will be explored in the near future in larger studies involving elderly patients.

References

- Stone RM, Mayer RJ. The unique aspects of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 1913-21. PMid:2230879

- Avvisati G, ten Cate JW, Mandelli F. Acute promyelocytic leukemia. Br J Haematol 1992; 81: 315-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb08233.x PMid:1390205

- Tallman

MS, Nabhan C, Feusner JH, Rowe JM. Acute promyelocytic leukemia:

evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood 2002; 99: 759-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V99.3.759 PMid:11806975

- Fenaux

P, Chomienne C, Degos L. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: biology and

treatment. Semin Oncol 1997; 24: 92-102. PMid:9045308

- Grimwade

D. The pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia: evaluation of the

role of molecular diagnosis and monitoring in the management of the

disease. Br J Haematol 1999; 106: 591-613. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01501.x PMid:10468848

- Rowley

JD, Golomb HM, Dougherty C. 15/17 translocation, a consistent

chromosomal change in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Lancet 1977; 1:

549-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 (77)91415-5

- de

The H, Chomienne C, Lanotte M, Degos L, Dejean A. The t(15;17)

translocation of acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses the retinoic acid

receptor alpha gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature 1990; 347:

558-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/347558a0 PMid:2170850

- Alcalay

M, Zangrilli D, Fagioli M, Pandolfi PP, Mencarelli A, Lo Coco F, Biondi

A, Grignani F, Pelicci PG. Expression pattern of the RAR alpha-Pml

fusion gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

1992; 89: 4840-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.11.4840 PMid:1317574 PMCid:49183

- Goddard

AD, Borrow J, Freemont PS, Solomon E. Characterization of a zinc finger

gene disrupted by the t(15;17) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Science

1991; 254: 1371-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1720570 PMid:1720570

- Sanz

MA, Martin G, Rayon C, Esteve J, González M, Díaz-Mediavilla J, Bolufer

P, Barragán E, Terol MJ, González JD, Colomer D, Chillón C, Rivas C,

Gómez T, Ribera JM, Bornstein R, Román J, Calasanz MJ, Arias J, Alvarez

C, Ramos F, Debén G. A modified AIDA protocol with anthracycline-based

consolidation results in high antileukemic efficacy and reduced

toxicity in newly diagnosed PML/raralpha-positive acute promyelocytic

leukemia. PETHEMA group. Blood 1999; 94: 3015-21. PMid:10556184

- Kanamaru

A, Takemoto Y, Tanimoto M, Murakami H, Asou N, Kobayashi T, Kuriyama K,

Ohmoto E, Sakamaki H, Tsubaki K. All-trans retinoic acid for the

treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Japan Adult

Leukemia Study Group. Blood 1995; 85: 1202-6. PMid:7858250

- Tallman

MS, Andersenn JW, Schiffer CA, Appelbaum FR, Feusner JH, Ogden A,

Shepherd L, Willman C, Bloomfield CD, Rowe JM, Wiernik PH.

All-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med

1997; 337: 1021-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199710093371501 PMid:9321529

- Sanz

MA, Lo Coco F, Martin G, Avvisati G, Rayón C, Barbui T, Díaz-Mediavilla

J, Fioritoni G, González JD, Liso V, Esteve J, Ferrara F, Bolufer P,

Bernasconi C, Gonzalez M, Rodeghiero F, Colomer D, Petti MC, Ribera JM,

Mandelli F. Definition of relapse risk and role of non-anthracycline

drugs for consolidation in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia:

a joint study of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA cooperative groups. Blood 2000;

96: 1247-53. PMid:10942364

- Fenaux

P, Chastang C, Chevret S, Sanz M, Dombret H, Archimbaud E, Fey M, Rayon

C, Huguet F, Sotto JJ, Gardin C, Makhoul PC, Travade P, Solary E,

Fegueux N, Bordessoule D, Miguel JS, Link H, Desablens B, Stamatoullas

A, Deconinck E, Maloisel F, Castaigne S, Preudhomme C, Degos L. A

randomized comparison of all transretinoic acid (ATRA) follone by

chemotherapy and ATRA plus chemotherapy and the role of maintenance

therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European

APL Group. Blood 1999; 94: 1192-200. PMid:10438706

- Park

JH, Qiao B, Panageas KS, Schymura MJ, Jurcic JG, Rosenblat TL, Altman

JK, Douer D, Rowe JM, Tallman MS. Early death rate in acute

promyelocytic leukemia remains high despite all-trans retinoic acid.

Blood 2011; 118: 1248-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-346437 PMid:21653939

- Lehmann

S, Ravn A, Carlsson L, Antunovic P, Deneberg S, Möllgård L, Derolf AR,

Stockelberg D, Tidefelt U, Wahlin A, Wennström L, Höglund M, Juliusson

G. Continuing high early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia: a

population-based report from the Swedish Adult Acute Leukemia Registry.

Leukemia 2011; 25: 1128-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.78 PMid:21502956

- Cunningham

I, Gee T, Reich L. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: treatment results

during a decade at Memorial Hospital. Blood 1989; 73: 1116-22.

PMid:2930837

- Mi JQ, Li JM, Shen ZX, Chen SJ, Chen Z. How to manage acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2012; 26: 1743-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.57 PMid:22422168

- Tallman MS, Altman JK. How I treat acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2009; 114: 5126-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-07-216457 PMid:19797519

- Ades

L, Chevret S, De Botton S, Thomas X, Dombret H, Beve B, Sanz M, Guerci

A, Miguel JS, Dela Serna J, Garo C, Stoppa AM, Reman O, Stamatoulas A,

Fey M, Cahn JY, Sotto JJ, Bourhis JH, Parry A, Chomienne C, Degos L,

Fenaux P; European APL Group. Outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia

treated with all trans retinoic acid ancd chemotherapy in elderly

patients: the European group experience. Leukemia 2005; 19: 230-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2403597 PMid:15565164

- Mandelli

F, Latagliata R, Avvisati G, Fazi P, Rodeghiero F, Leoni F, Gobbi M,

Nobile F, Gallo E, Fanin R, Amadori S, Vignetti M, Fioritoni G, Ferrara

F, Peta A, Giustolisi R, Broccia G, Petti MC, Lo-Coco F; Italian GIMEMA

Cooperative Group. Treatment of elderly patients (> or =60 years)

with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Results of the

Italian multi center group GIMEMA with ATRA and idarubicin (AIDA)

protocols. Leukemia 2003; 17: 1085-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2402932 PMid:12764372

- Latagliata

R, Breccia M, Fazi P, Vignetti M, Di Raimondo F, Sborgia M, Vincelli D,

Candoni A, Salvi F, Rupoli S, Martinelli G, Kropp MG, Tonso A, Venditti

A, Melillo L, Cimino G, Petti MC, Avvisati G, Lo-Coco F, Mandelli F;

GIMEMA Acute Leukaemia Working Party.GIMEMA AIDA 0493 amended protocol

for elderly patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Long-term

results and prognostic factors. Br J Haematol 2011; 154: 564-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08593.x PMid:21751984

- Sanz

MA, Vellenga E, Rayón C, Díaz-Mediavilla J, Rivas C, Amutio E, Arias J,

Debén G, Novo A, Bergua J, de la Serna J, Bueno J, Negri S, Beltrán de

Heredia JM, Martín G. All-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline

monochemotherapy for the treatment of elderly patients with acute

promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2004; 104: 3490-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-04-1642 PMid:15292063

- de

la Serna J, Montesinos P, Vellenga E, Rayón C, Parody R, León A, Esteve

J, Bergua JM, Milone G, Debén G, Rivas C, González M, Tormo M,

Díaz-Mediavilla J, González JD, Negri S, Amutio E, Brunet S, Lowenberg

B, Sanz MA. Causes and prognostic factors of remission induction

failure in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with

all-trans retinoic acid and idarubicin. Blood 2008; 111: 3395-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-07-100669 PMid:18195095

- Ono

T, Takeshita A, Kishimoto Y, Kiyoi H, Okada M, Yamauchi T, Tsuzuki M,

Horikawa K, Matsuda M, Shinagawa K, Monma F, Ohtake S, Nakaseko C,

Takahashi M, Kimura Y, Iwanaga M, Asou N, Naoe T; Japan Adult Leukemia

Study Group. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors of elderly

patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Sci 2012; 103;

1974-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02390.x PMid:22834728

- Lengfelder

E, Hanfstein B, Haferlach C, Braess J, Krug U, Spiekermann K, Haferlach

T, Kreuzer KA, Serve H, Horst HA, Schnittger S, Aul C, Schultheis B,

Erben P, Schneider S, Müller-Tidow C, Wörmann B, Berdel WE, Sauerland

C, Heinecke A, Hehlmann R, Hofmann WK, Hiddemann W, Büchner T; German

Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group (AMLCG). Outcome of elderly

patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: results of the German Acute

Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. Ann Hematol 2013; 92: 41-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00277-012-1597-9 PMid:23090499 PMCid:3536950

- Breccia

M, Lo Coco F. Arsenic trioxide for management of acute promyelocytic

leukemia: current evidence on its role in front-line therapy and

recurrent disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012; 13: 1031-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2012.677436 PMid:22468778

- Zhang

Y, Zhang Z, Li J, Li L, Han X, Han L, Hu L, Wang S, Zhao Y, Li X, Zhang

Y, Fan S, Lv C, Li Y, Su Y, Zhao H, Zhang X, Zhou J. Long-term efficacy

and safety of arsenic trioxide for first-line treatment of elderly

patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer

2013; 119: 115-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27650 PMid:22930197

- Stasi

R, Evangelista ML, Buccisano F, Venditti A, Amadori S. Gemtuzumab

ozogamicin in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Canc Treat Rev

2008; 34. 49-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.09.001 PMid:17942233

- Paietta E. Expression of cell-surface antigens in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2003; 16: 369-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1521-6926 (03)00042-2

- Guglielmi

C, Martelli MP, Diverio D, Fenu S, Vegan ML, Cantù-Rajnoldi A, Biondi

A, Cocito MG, Del Vecchio L, Tabilio A, Avvisati G, Basso G, Lo Coco F.

Immunophenotype of adult and childhood acute promyelocytic leukemia:

correlation with morphology and type of PML gene breakpoint: a

cooperative Italian study on 196 cases. Br J Haematol 1998; 102:

1035-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00871.x PMid:9734655

- Michieli

M, Damiani D, Ermacora A, Geromin A, Michelutti A, Masolini P,

Baccarani M. P-glycoprotein (PGP), lung resistance-related protein

(LRP) and multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) expression in

acute promyelocytic leukemia. Br J Haematol 2000; 108: 703-09. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01957.x PMid:10792272

- Paietta

E, Andersen J, Racevskis J, Gallagher R, Bennett J, Yunis J, Cassileth

P, Wiernik PH. Significantly lower P-glycoprotein expression in acute

promyelocytic leukemia than in other types of acute myeloid leukemia:

immunological, molecular and functional analyses. Leukemia 1994; 8:

968-73. PMid:7516029

- Lo

Coco F, Cimino G, Breccia M, Noguera NI, Diverio D, Finolezzi E,

Pogliani EM, Di Bona E, Micalizzi C, Kropp M, Venditti A, Tafuri A,

Mandelli F. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) as a single agent for

molecularly relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2004; 104:

1995-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-04-1550 PMid:15187030

- Breccia

M, Cimino G, Diverio D, Gentilini F, Mandelli F, Lo Coco F. Sustained

molecular remission after low dose gemtuzumab ozogamicin in elderly

patients with advanced acute promyelocytic leukemia. Haematologica

2007; 92: 1273-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.11329 PMid:17768126

- Finizio

O, Pezzullo L, Rocco S, Bene L, De Rosa C, Nunziata GR, Mettivier V.

Combination of all-trans retinoic acid and gemtuzumab ozogamicin in an

elderly patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia and severe cardiac

failure. Acta Haematol 2007; 117: 188-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000097880 PMid:17167240

- Disperati

P, Minden MD, Gupta V, Schimmer AD, Schuh AC, Yee KW, Kamel-Reid S,

Chang H, Xu W, Brandwein JM. Acute promyelocytic leukemia in patients

aged 70 years and over—a single center experience of unselected

patients. Leuk Lymphoma 2007; 48: 1654-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10428190701472005 PMid:17701604

- Finsinger P, Breccia M, Minotti C, Carmosino I, Cannella L, Volpicelli P, Vozella F, Stefanizzi C, Loglisci G, Cimino G, Foà R, Latagliata R. Scute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) in patients aged > 70 years. Blood 2009; 114: 4160 (ASH meeting abstract)

- Ferrara

F, Finizio O, D'Arco A, Mastrullo L, Cantore N, Musto P. Acute

promyelocytic leukemia in patients aged over 60 years: multi center

experience of 34 consecutive unselected patients. Anticancer Res 2010;

30: 967-71. PMid:20393021

- Thomas

X, Dombret H, Cordonnier C, Pigneux A, Gardin C, Guerci A, Vekhoff A,

Sadoun A, Stamatoullas A, Fegueux N, Maloisel F, Cahn JY, Reman O,

Gratecos N, Berthou C, Huguet F, Kotoucek P, Travade P, Buzyn A, de

Revel T, Vilque JP, Naccache P, Chomienne C, Degos L, Fenaux P.

Treatment of relapsing acute promyelocytic leukemia by all-trans

retinoic acid therapy follone by timed sequential chemotherapy and stem

cell transplantation. APL Study Group. Acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Leukemia 2000; 14: 1006-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2401800 PMid:10865965

- Soignet

SL, Frankel SR, Douer D, Tallman MS, Kantarjian H, Calleja E, Stone RM,

Kalaycio M, Scheinberg DA, Steinherz P, Sievers EL, Coutré S, Dahlberg

S, Ellison R, Warrell RP Jr.United States multi center study of arsenic

trioxide in relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2001;

19: 3852-60. PMid:11559723

- Estey

E, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, Faderl S, Verstovsek S, Jones D,

Kantarjian H. Use of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide a

san alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic

leukemia. Blood 2006; 107: 3469-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-10-4006 PMid:16373661

- Breccia

M, Cicconi L, Minotti C, Latagliata R, Giannì L, Lo-Coco F. Efficacy of

prolonged therapy with combined arsenic trioxide and ATRA for relapse

of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2011; 96: 1390-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.045500 PMid:21659361 PMCid:3166113