Received: December 9, 2013

Accepted: February 7, 2014

Meditter J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014013, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.013

This article is available on PDF format at:

Arben Pilaca1, Gentian Vyshka2, Arben Pepa3, Kastriot Shytaj4, Valentin Shtjefni5, Arben Boçari6, Arben Beqiri7 and Dhimitër Kraja1

1Service

of

Infective Diseases, University Hospital Centre “Mother Theresa”,

Tirana, Albania

2Biomedical and Experimental Department, Faculty

of

Medicine, University of Tirana, Albania

3Obstetrical and Gynecological Hospital, Tirana,

Albania

4Faculty of Medical and Technical Sciences,

University

of Medicine in Tirana, Albania

5Institute of Veterinary Care, Tirana, Albania

6Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Agricultural

University of Tirana, Albania

7Service of Surgery, University Hospital Centre

“Mother Theresa”, Tirana, Albania

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Echinococcosis is an endemic zoonosis in the Mediterranean area, with Albania interested actually to a level that is becoming a public health concern. Authors describe preliminary data from the only tertiary (university) medical facility of Albania, positioned in the capital of the country (Tirana), with 333 new cases diagnosed and treated during the period 2005 – 2011. Out of all these 333 new cases an impressive majority of 91% had a surgical treatment right from the first admission, rendering the disease almost a surgical exclusivity. Even more, 80% of all patients from the study group were hospitalized straightforwardly in surgical wards, with options of surgical intervention’s percentages outrunning figures from other sources and authors of the same geographical area. Such a situation, together with a very important level of patients’ origin from highly urbanized areas such as those of the capital, suggest the necessity of well-organized interventions, among which might be the mandatory notification of all human cases with Echinococcus infection. |

Introduction

Echinococcosis

is a chronic and zoonotic infection, actually representing one of the

three major helminth diseases that cause a major public health concern

especially in developed countries, together with cysticercosis and

fascioliasis.[1]

Echinococcosis is synonymously known as the hydatid disease, with the

term ‘hydatid’ deriving from the Greek ‘hydōr’,

meaning water, and thus reflecting the cystic character of the

infective process. Controversial data regarding the epidemiology and

the severity of the infection among humans are available, with some

authors offering an optimistic perspective of a dramatic fall in the

incidence and prevalence of the most common form of the disease, namely

the cystic echinococcosis.[2]

However, and in spite of large preventive

and therapeutic interventions, cystic echinococcosis remains a frequent

condition in developed and undeveloped countries.[3,4]

Classic cystic echinococcosis (CE) is caused by E. granulosus, one

of the two major

species of the genus Echinococcus able to infect humans. E. multilocularis

is the second most important pathological species of this genus. These

species are respectively responsible for CE, and for the alveolar

echinococcosis (AE). AE is caused from E. multilocularis

and represents the other clinical picture related to these tapeworms,

able to infest humans as well as other mammalian intermediate hosts.

Wildlife animals and domesticated pets might be infested in a variety

of ways or forms, and from different species of Echinococcus.[5,6]

Thus, E. granulosus,

E. multilocularis,

E. vogeli and

E. oligarthus

have shown to have different but intrinsic pathological potential

regarding the ability to infest humans, with other species of the same

genus having only un unclear infective potential, if at all.[7,8]

Multiple studies have scrutinized risk factors and environmental

changes that influence on the global spread of the infection. Host

characteristics as well as host population dynamics and density are

among the most studied in a variety of animals. Obviously canids, dogs

in first line, serve as definitive host; foxes, jackals, dingo, hyena,

wolves and raccoon-dogs might be definitive hosts as well.[8,9] The

list of intermediate hosts might be even longer, with rodents on the

top, and with a variety of domesticated animals (sheep, pigs, goats)

serving that role, but without excluding even exotic or at risk of

extinction wildlife organisms, such as hippopotamus, giraffes,

antelopes (kudu) and so on.[8,10-12]

Echinococcosis is considered as an endemic zoonotic disease in the

Mediterranean area.[2] Some authors

suggest, with obvious and sound

reasons, that this disease with variegate clinical features, is posing

a severe threat even to the public health level.[13]

Both major

clinical forms, CE and AE, have been found present in different

Mediterranean countries, although CE and E. granulosus,

having the latter an intrinsic affinity for warmer climates, represent

the overwhelming form. Much more disturbing is the fact that E. multilocularis,

the causative factor of AE, generally considered as a species occurring

only sporadically in this geographical area, is however recently found

to expand his habitat continuously.[13,14]

Although representing a major public health problem and a considerable

burden of disease for several Mediterranean countries, epidemiological

data are scarce, and the precise incidence among humans is unknown for

CE as well as for AE in Albania and in countries neighboring it.[15]

With a worldwide prevalence of approximately six million, CE needs

global approaches and strategies to prevent further progression.[3]

Among the factors explaining this persistence of the disease, sources

quote the climate changes and the warmer temperatures.[16,17]

Host

density is another major factor; if there are no epidemiological data

regarding human incidence of echinococcosis in Albania, no data either

are offered regarding stray dog populations in our country.

The aim of the present study was to systematize preliminary data

gathered from our University Hospital Facility in Tirana, regarding

cases of echinococcosis diagnosed and treated during recent years

(2005-2011). An insight to epidemiological characteristics of this

zoonosis in Albania is given as well, and a geographical distribution

of cases was made, aiming at localizing districts of the country being

at “high risk” for possible outbreaks, due to the actual high

expression of the disease.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective and single-centre study was performed in the only

University Hospital Centre of Tirana, capital of Albania. Due to

panoply of reasons, district hospitals almost constantly refer cases to

this facility; however the data are not meant to represent the overall

country presence of the disease, since many cases of Echinococcosis

might go untreated.

UHC of Tirana is organized in several services that function as

clinical wards; all data and medical files are deposited in a central

statistical office, with medical doctors and authorized personnel able

to access their content decades after the discharge of a patient.

This is a descriptive study of the hospitalizations at the University

Hospital Centre “Mother Theresa” of Tirana (UHC of Tirana), during the

period 2005 – 2011, regarding all cases whose admission diagnosis was ‘echinococcosis’.

A study of the cases was made after carefully controlling the central

statistical office of UHC of Tirana, taking note of following details:

Results

During the period 1st

January 2005 –

31st December 2011 we had a total of 385 hospitalizations with the

admission diagnosis of ‘Echinococcosis’, for a total of 333 patients

(de novo and recurrent admissions), with 303 cases operated.

Only one case

had a fatal outcome, and is not included in the database of the Table 2.

According to our data, 91% of the cases of echinococcosis admitted in

the UHC of Tirana during a seven years period, was initially admitted

or referred during the same hospitalization at the UHC, in a surgical

facility, and underwent a surgical intervention.

The mean period of hospitalization

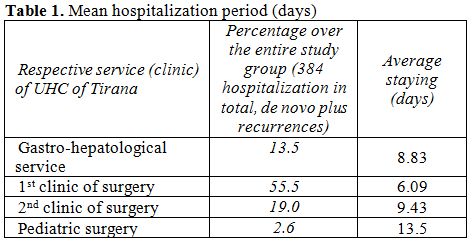

is given in the Table 1,

where

are considered the services of UHC accounting for the majority of all

cases admitted during this period.

The mean age

of patients

forming the study group (a total of 333 patients) resulted 36 years old

(from a minimum of six month, to a maximum age of 77 years).

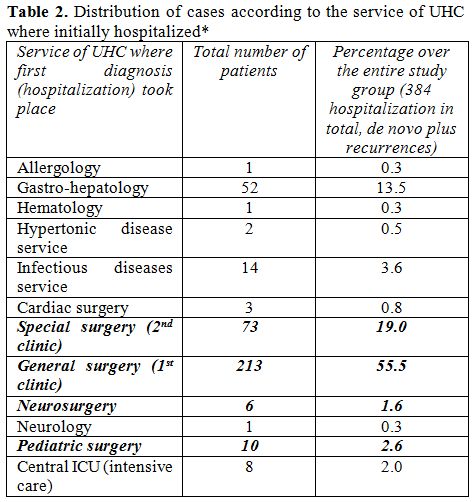

Overall distribution of cases in the different

clinical services of UHC of Tirana is described at the Table 2.

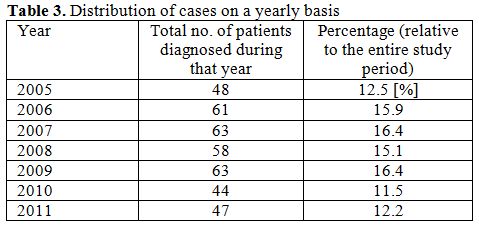

Time distribution (total yearly figures from 2005 to 2011) is described

in the Table 3.

Worthwhile is stating that it has been an almost constant figure year

after year (2005 – 2011) with a minimum of 44 cases during the year

2010 and a maximum of 63 cases (2007, 2009), thus the yearly level of

newly diagnosed cases did not changed substantially.

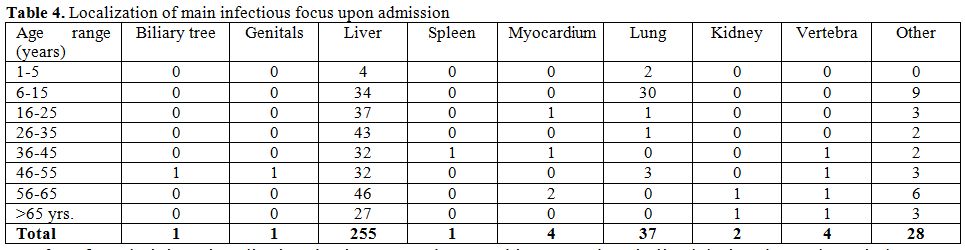

The clinical localization of the disease (visceral distribution; in

terms of the main focus upon admission) is described in the Table 4. The

distribution of cases

is made in separate age ranges (decennia).

| Table 1. Mean hospitalization period (days) |

| Table 2. Distribution of cases according to the service of UHC where initially hospitalized* |

| Table 3. Distribution of cases on a yearly basis |

| Table 4. Localization of main infectious focus upon admission |

The geographical

distribution of the cases was made accordingly with

the administrative map of Albania, shown in the Figure 1.

In order to simplify the exposition of data, we have separated

graphically the districts of the country in the map below through

illustrating the number of cases with a different color.

Thus, in the map below (Figure

1)

we have separated different district of the country through using

following illustrative colors:

Blue;

for administrative

districts having more than thirty cases hospitalized during the study

period;

Yellow-orange;

for

districts having 10-30 cases hospitalized during the same period;

Green;

for districts

having 5-9 hospitalizations in total (2005-2011);

Grey;

for districts

having less than five cases in total for the study period.

According to the data we gathered, we had a total of 99 patients

hospitalized during the study period, originating from the district of

Tirana (capital of the country, and surrounding areas). Thus, this city

and the respective district are shown in the map with blue color.

In fact, the absolute number of cases coming from this district was

overwhelmingly higher when compared with other districts of the

country.

With yellow-orange

color

there

are shown a total of eight districts of Albania, including four

northern administrative districts (namely Kukës [with 30 patients],

Dibra [17 patients], Shkodra [13 patients] and Tropoja [10 patients]).

With the same color we illustrated four other districts almost

symmetrically positioned in the lower half of the country’s map,

including a central Albanian district (Elbasan with 10 patients); a

south-west district close to the Adriatic seashore (Fier with 13

patients); a south-east district neighboring Greece (Korça with 21

patients) and a southern district almost at the lower extreme of the

map (Gjirokastra with 14 patients).

Other administrative districts of the country having less than 10

hospitalizations during the entire study period were depicted in green and grey

(see map). The distribution of the cases in these districts followed a

disparate order as well, although districts close to the Adriatic

seashore had somehow higher absolute figures (port cities of Durrës and

Vlora [shown in green] with 9 patients each); when compared to southern

– southeastern districts neighboring Greece, with lower absolute

figures (Devoll, Delvina and Skrapar [shown in grey] each of them with

1 patient for the entire study period).

The size of cysts was registered only in a minority of our cases (114 patients), and the available data were collected from echography findings. Due to this gap we cannot refer exhaustive values of cyst sizes in our study group; however the size of the cysts’ diameter varied from a minimum of 2 centimeters to a maximum of 15 centimeters, in this subgroup of patients where the cyst size was registered.

Discussion

Echinococcosis (hydatidosis) is an endemic disease for the

Mediterranean area, and Albania will obviously be interested to the

same extent as other countries of the region. Since no exhaustive or

thorough statistical and epidemiological study is available, comparing

the epidemiological situation with that of neighboring countries still

remains a challenge.

As far as it regards a non-reportable infection, collecting statistics

for an entire country might be virtually impossible. Nevertheless,

attempts to profile and to analyze echinococcosis in endemic regions

have been made.[18] Another non

trivia0l difficulty is related to the

panoply of clinical features through which echinococcosis might

present, becoming in certain situation a diagnostic conundrum. Our

study confirms as well an almost universal finding, that the majority

of cases of echinococcosis are confined to the liver and to the

lungs.

Hydatid cyst will show a clear mass effect and therefore will be a

surgical exclusivity in many settings. Highly peculiar clinical forms

are reported, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, left ventricle hydatid cyst

mimicking heart attack, genital localization with scrotal extension and

so on.[19-21] Such a variety of

localizations is related to the fact

that hydatidosis affects almost all body regions.

In the present paper we have encountered two worth mentioning phenomena:

A very high proportion of patients (99 from the total study group of 333) originating from the district of Tirana, comprising the capital and its suburban areas;

An excessively high proportion of surgical approach as well, with 91% of all patients forming our study group that were operated during the initial admission at the UHC of Tirana, and even with almost 80% of all patients admitted straightforward in a surgical facility (here including general, special, pediatric and neurological surgery services).

The fact that we had the majority of cases originating from Tirana

might be artifactual, since UHC itself is situated in this capital

city, and inhabitants of the district will have an easier access to the

facility. However, UHC of Tirana is the single tertiary (university)

hospital in Albania; therefore all difficult and complicated cases will

be referred herein. This is much true nowadays when almost all

specialized medical help, staff and equipment, is focused inside this

centre, with periphery and remote districts suffering from inexistent

or incompetent medical services.

The high proportion of cases originating from Tirana might be also

related to other reasons. High and aggressive urbanization of the

capital and its suburban areas, with the sanitary problems that such a

process with entail, here including even the garbage disposal and

landfills (Sharra landfill among other) in the vicinity of the city,

have been at the focus of media reports.[22]

The presence of

domesticated animals that are part of the transmitting chain of this

infection to humans, such as sheep and dogs, inside landfills and in

the city itself has been a constant concern. Serious attempts have been

made to study the intestinal parasite fauna of dogs of the suburban

area of Tirana, with Echinococcus being part of the list.[23]

The other major suggestion of the present study was the fact that

actually in Albania, and in the only tertiary medical facility of the

country (UHC), echinococcosis has practically become a surgical

exclusivity. Approximately 90% of the entire study group admitted with

this diagnosis during 2005-2011 ended up with a surgical intervention.

But probably the most important fact is that 80% of all patients were

right from the start hospitalized in a surgical ward, thus the

condition has (almost) never been consulted from infectious disease

specialists, with treatment focused alone in the surgery. In fact, from

all patients treated surgically, only 23 of them had later (within six

months from the intervention) an infectionist consultancy, and none of

these patients were receiving an ad hoc pharmacological therapy prior

to surgery.

This very high level of surgical interventions contrasts with findings

from other tertiary centers, with authors from countries neighboring

Albania referring surgery as a single option only in 10% of the study

group.[4]

Under these circumstances, and in view of the endemic situation in the

Mediterranean area, mandatory notification of all human cases of

Echinococcus infection, through taking necessary steps toward rendering

the condition obligatorily a reportable one, seems more than logical.

References

[TOP]