Received: June 3, 2013

Accepted: January 7, 2014

Meditter J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014017, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.017

This article is available on PDF format at:

Ruben Fernandez-Alvarez1, ME. Gonzalez1, Almudena Fernandez1, AP. Gonzalez-Rodriguez3, JM Sancho4, Francisco Dominguez2 and Carmen Fernandez1

1Department

of Hematology, Hospital de Cabueñes,

Gijon, Spain.

2Department of Pathology, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijon, Spain.

3Stem Cell Transplant Unit, Hospital

Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain.

4Clinical Hematology Department, ICO-Hospital

Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Lymphomatoid

granulomatosis (LYG) is a very rare Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) associated

B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. We report the case of a

41-year-old man who presented with fever and respiratory symptoms.

Computed tLymphomatoid

granulomatosis (LYG) is a very rare Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) associated

B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. We report the case of a

41-year-old man who presented with fever and respiratory symptoms.

Computed tomography showed multiple nodules in both lung fields.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for EBV was positive in

bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy of lung node yielded a diagnosis of

LYG, grade III. Shortly after initiation of treatment with agressive

chemotherapy, neurological deterioration appeared. Neuroimaging

findings revealed hydrocephalus and PCR analysis of the cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) was positive for EBV. Treatment with intravenous rituximab

led to rapid reduction of EBV load in CSF, along with clinical and

radiological improvement. After completion of treatment with

immunochemotherapy, an autologous stem cell transplantation was

performed. Patient stays in remission 18 months after diagnosis.

|

Introduction

Lymphomatoid

granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder

characterized by an angiocentric and angiodestructive lymphoid

proliferation. Cytological composition consists of large atypical B

cells (which are Epstein-Barr [EBV]-positive) accompanied by reactive T

cells.[1] Progression to a diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) occurs in up to 15% of cases,[2] and distinction between high grade

LYG and lymphoma can be subtle.

Clinical presentation is heterogeneous. Pulmonary involvement is almost

always present, while other common sites include central nervous system

(CNS) and skin.[2]

Currently, LYG is considered an EBV related B-lymphoproliferative

disorder,[3]

similar to other lymphoproliferative disorders such as

post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease. Although LYG is most

commonly diagnosed in patients without over immunodeficiency, it is

probable that most cases display an immunologic defect that is unable

to adequately control EBV-infected B-cells.[4]

Disease course is unpredictable and there is no clearly established

treatment. After the recognition of EBV-positive B cells involvement,

rituximab has been considered as a promising treatment.[5]

We report here a case of an agressive LYG involving skin, lungs and

CNS, with documented active EBV replication, and effective treatment

with chemotherapy plus rituximab.

Case Report

A 41-year-old male presented with fever, weight loss and cough.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous plaque lesions on

his back. Laboratory results revealed elevated serum lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH) level, mild anemia and elevated C reactive protein

level. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed ground glass infiltrates at

lower lobes. Antibiotics were started, without improvement. Serologic

tests for Mycoplasma, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and Human

Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative, whereas Cytomegalovirus

(CMV) and EBV were positive, indicating previous infections. Additional

workup showed negative antinuclear antibodies and antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Two skin biopsies were performed,

showing a dense T-cell lymphoid infiltrate, EBV-ISH negative. Steroid

treatment was started (1 mg/kg/day), and fever and skin lesions

disappeared rapidly. However, patient developed confusion, gait

imbalance and diplopia.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed: 10 white blood cells (WBC,

all mononuclear), protein 1.11 g/L, and glucose 71 mg/dl. CSF flow

cytometry detected a polyclonal T-cell population. Cranial magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse hyperintense lesions involving

white matter around ventricles, without contrast enhancement (Figure 1[a]).

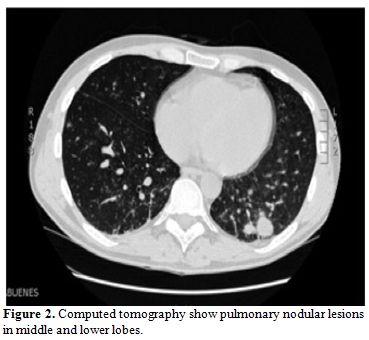

Two weeks later, respiratory symptoms worsened and a second CT revealed

multiple pulmonary nodules in middle and lower fields, some of them

with cavitation (Figure 2).

Microbiological tests of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were negative,

except amplification of EBV-DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR),

that yielded 4080 copies/mL. Biopsy of lung node showed a highly

polymorphic infiltrate of large and atypical lymphoid cells, displaying

an angiocentric and angiodestructive distribution (Figure 3[a]).

Immunostains showed B-cell proliferation (PAX-5+, MUM-1+ -Figure 3[b]-) with

very intense EBER expression (Figure

3[c]), together with T-cell proliferation (Figure 3[d]).

These findings led to suspicion of T-cell lymphoma, but after later

review, final diagnosis was LYG, grade III. Complete staging revealed

mild hepatosplenomegaly, while bone marrow was normal.

| Figure 2. Computed tomography show pulmonary nodular lesions in middle and lower lobes. |

Because

of suspicion of T-cell lymphoma with probable CNS involvement,

treatment was started with a high-dose methotrexate (MTX) based

protocol (ifosfamide, 1500 mg/m2

daily for 5 days plus mesna; etoposide, 150 mg/m2

daily for 3 days; cytarabine, 100 mg/m2

daily for 3 days; and MTX, 3 g/m2

on Day 5, with leucovorin rescue) plus intrathecal application of MTX,

Ara-C, and hydrocortisone. Shortly after, the patient developed

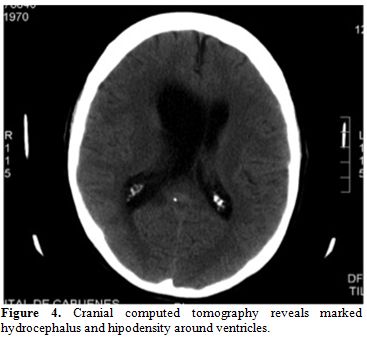

somnolence, incoherent speech, and nystagmus. Cranial CT scan revealed

important hydrocephalus with worsening of previous findings (Figure 4).

An Ommaya reservoir was placed and examination of CSF showed a WBC

count of 8 cells/mL, with normal glucose and protein levels. The Gram

staining and culture were negative. PCR analysis for EBV was positive,

yielding 43700 copies/mL. HHV-6, CMV, HSV, VZV and JCV were negative by

PCR assay.

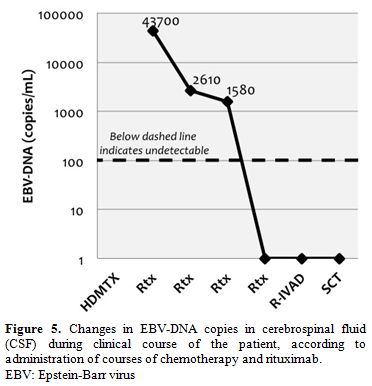

At this stage, treatment with rituximab (375 mg/m2/iv)

was added, once weekly for 4 doses. EBV-DNA copies in CSF rapidly

declined in the following weeks (Figure

5).

A cranial MRI performed after completion of rituximab demonstrated

significant improvement, and pulmonary CT scan showed decreasing size

of lung nodules.

Once patient improved, he received one further cycle of the same

high-dose MTX-protocol, together with rituximab and intrathecal

chemotherapy. Autologous stem cell transplantation was scheduled. The

preparative regimen consisted of total body irradiation (10 Gy) and

cyclophosphamide (100 mg/Kg) without major complications. On follow-up,

both cerebral MRI and pulmonary CT scan have not shown progression. 18

months after the diagnosis, patient remains in remission.

| Figure 4. Cranial computed tomography reveals marked hydrocephalus and hipodensity around ventricles. |

| Figure 5. Changes in EBV-DNA copies in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during clinical course of the patient, according to administration of courses of chemotherapy and rituximab. EBV: Epstein-Barr virus |

Discussion

LYG was first described by Liebow et al.[6]

in 1972,

and originally was considered a form of T-cell lymphoma, based on the

predominant T-cell infiltrate. It was later demonstrated that LYG is an

EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, accompanied by a

large number of reactive T-cells.[7]

The distinctive

morphologic feature of LYG is an angiocentric and angiodestructive

lymphoid infiltrate, with infiltration of the vascular wall and

variable degree of necrosis. Currently, LYG is considered a

lymphoproliferative disorder with a broad pathological and clinical

spectrum. Lipford et al.[8]

classified LYG lesions

into 3 histologic grades on the basis of the degree of cytologic atypia

and necrosis. The number of EBV-positive cells correlates with

histologic grade.1 In grade 1 lesions, EBV-positive cells are

infrequent whereas they are readily detected in grade 2 and 3 lesions.

It is important to note that the number of EBV-cells may vary over time

or between sites, as reflected in our case (skin, grade 1; lungs, grade

3).

Clinically, LYG demonstrates predilection for men, most often in adults

between the 4th and 6th decades of life. The lungs are virtually always

affected in LYG.2 Radiologically, pulmonary lesions are heterogeneous,

from diffuse infiltrates to nodules.[9]

According to its angiodestructive nature, occasional

cavitation/necrosis is seen, as in our case.

Skin is affected in approximately 45% of patients. Cutaneous lesions

may appear before the pulmonary disorder,[10]

as in our case. Dermatologic manifestations are diverse, but most

typically appear as nodules. The clinical pattern of the cutaneous

lesions correlates with histological grade. Beaty et al.[10]

showed that the plaque lesions were negative for EBV and demonstrated

IgH polyclonal patterns. In contrast, angiodestruction, cellular atypia

and EBV positivity are more common in nodules. Our case presented

erythematous plaques, without EBV, which is consistent with grade 1 LYG.

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement occurs in 25-35% of cases,

usually accompanying pulmonary lesions.[2]

Neuroimaging findings are variable. Mizuno et al.[11]

reviewed 45 LYG cases involving CNS, and classified them as tumorous

lesions and non-tumorous lesions (multiple focal lesions or diffuse

involvement, as in our case). Most common finding consists of multiple

focal lesions involving the white matter, deep grey matter, or the

brainstem,[12] showing high signal

intensity (on

T2-weighted images) and contrast enhancement; however it's possible

that some lesions only manifest T2 prolongation. Our case presented

diffuse involvement of white matter, with typical T2 hyperintensity,

but did not show contrast enhancement. Histologic documentation of

brain lesions is not usually available and CSF analysis presents low

sensitivity for the diagnosis of LYG in the brain,[12]

as in our case. High EBV-DNA levels were found in our case, which is

consistent with the biology of the process. No previous reports exist

on the detection of EBV-DNA in CSF of patients with cerebral LYG, so

significance of this finding is unknown. We think measurement could be

clinically useful for diagnosis support and for monitoring treatment

response. In our case, virologic response in CSF correlated with

radiological and clinical response.

LYG is considered an EBV driven process. Its implication was first

described in 1990 when EBV DNA was found in tissue samples of 21 out of

29 patients with LYG.[3] Evidence

of subtle immune deficits has been found in otherwise immunocompetent

individuals with the disease.[4]

Disease hypothesis suggests LYG arise in the setting of a dysregulation

of EBV surveillance (deficit of EBV-specific CD8 T-cells). Progressive

oncogenic events transform lower grade to higher grade disease: grades

1 and 2 are polyclonal or oligoclonal and immune dependent; grade 3

disease is monoclonal and immune independent.[13]

Therapy of LYG includes corticosteroids, chemotherapy or observation,

generally with poor outcomes,[14]

as these therapies can potentially worsen the intrinsic immunologic

defect. In our case, neurological condition deteriorated after steroids

and chemotherapy. We hypothesized that decline in cellular immunity

caused an increase of EBV infected cells, as we found a strikingly high

viral load of EBV in CSF.

A risk-adapted treatment strategy has been developed by the US National

Cancer Institute (NCI),[13]

with the objective of improving immunologic defect and eradicating

EBV-positive B cells. They use interpheron alpha for low-grade LYG, and

immunochemotherapy (rituximab plus CHOEP regimen) for high-grade LYG.

Rituximab is considered a promising treatment for LYG, after the

recognition of EBV-positive B-cells involvement. Recently, Hernandez et

al.[5] reviewed the use of

rituximab in LYG. To date,

a total of 22 cases have been reported: 11 patients had improvement (6

in monotherapy, 5 in combination with other drugs), whereas 7 patients

progressed. The role of rituximab for CNS lesions is also unclear: of

22 patients reported, only 7 had CNS involvement.[5,15-19] Responses were successful in 3

cases, all of them received rituximab as monotherapy.[15-17]

In conclusion, our case presented asynchronous manifestations of LYG at

skin, lungs and CNS, with detection of EBV-DNA at sites of involvement.

Rituximab was effective in the treatment, and we demonstrate that

clearance of EBV viral load in CSF correlated with clinical and

radiological improvement.

References

[TOP]