Received: January 15, 2014

Accepted: March 10, 2014

Meditter J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014028, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.028

This article is available on PDF format at:

Elisabetta Abruzzese, Malgorzata Monika Trawinska, Alessio Pio Perrotti and Paolo De Fabritiis

Hematology,

S. Eugenio Hospital, Tor Vergata University.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract The

management of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) during

pregnancy has become recently a matter of continuous debate. The

introduction of the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) in clinical

practice has dramatically changed the prognosis of CML patients; in

fact, patients diagnosed in chronic phase can reasonably expect many

years of excellent disease control and good quality of life, as well as

a normal life expectancy, including the necessity to address issues

relating to fertility and pregnancy. Physicians are frequently being

asked for advice regarding the need for, and/or the appropriateness of,

stopping treatment in order to conceive. In this report, we will review

the data published in terms of fertility, conception, pregnancy,

pregnancy outcome and illness control for TKI treated CML patients, as

well as how to manage a planned and/or unplanned pregnancy.

|

Introduction

The

hybrid BCR-ABL gene and its tyrosine kinase constitutionally active

recombinant fusion protein (p210 BCR-ABL) deriving from the reciprocal

translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 is associated with the

clinical development of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).[1-2]

This

fusion results in the expression of two forms of protein-tyrosine

kinases: p190 (BCR-ABL) and p210 (BCR-ABL) with subsequent

dysregulation of intracellular signaling that drive cells to enhanced

proliferative capability and resistance to apoptosis.

The presence of this well defined pathogenetic defect at the molecular

level led to the development of Imatinib, a tyrosin kinase inhibitor

able to block the BCR-ABL aberrant molecule, thus shutting down the

leukemia phenotype.[3-4]

Imatinib (Glivec, Novartis), is the first of a series of tyrosin kinase

inhibitors (TKIs), a group of drugs used to manage patients with

chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) through the competitive ATP inhibition

at the catalytic binding site of the bcr-abl protein.[5]

The second and

third generation TKIs include Nilotinib (Tasigna, Novartis), Dasatinib

(Sprycel, Bristol Myers Squibb), Bosutinib (Bosulif, Pfizer), and the

recently approved Ponatinib (Iclusig, Ariad Pharma).

The introduction of TKIs in clinical practice has dramatically changed

the prognosis of CML patients. Data derived from first line therapy

(IRIS Study) at 7 years follow up, confirmed one year later, reports

cumulative best rates of complete cytogenetic remission (CCR) of 82%,

and an estimated overall survival of 89%.[6-8]

Patients diagnosed in chronic phase can reasonably expect many years of

excellent disease control and good quality of life (QoL); furthermore,

patients in an optimal response can reach a life expectancy similar to

the non-leukemic, same age, population.[9]

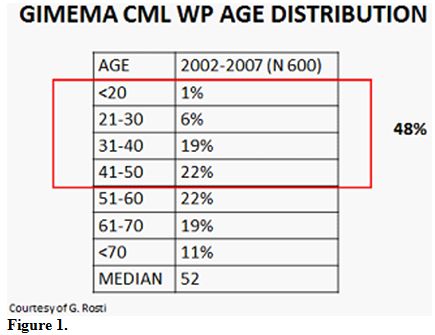

Even if a higher median age at diagnosis (55-60 y.o.) were reported,

the GIMEMA registry of CML has reported that approximately 50% of

patients at diagnosis are in reproductive age (Figure 1).

This has addressed issues relating fertility and pregnancy and

physicians are frequently asked for advice regarding the need and/or

the appropriateness of stopping treatment in order to conceive.

| Figure 1 |

TKIs in Animal Model

Imatinib:

Studies on either males or females rats and mice have shown that

Imatinib administered to fertile animals has a teratogenic but not

gonadotoxic activity.

However, when male rats were given Imatinib at dosages between 20 and

60mg/kg (corresponding to the human dose of 200-600mg/d) lower

testicular weight and reduction of sperm mobility were observed at

higher dosage. If similar dosages were given to immature rats,

interference with the normal process of testis maturation was noticed,

while, at sexual maturity, a normal number of sperm counts, motility,

maturation and development and higher levels of FSH and LH were

registered.[10] Effects of Imatnib

on ovary were unremarkable, so that

the fertility of male and female rats was not affected.

The effects on gestation differed by the dosage utilized: teratogenic

effects of skull and bone formation (exencephaly, encephalocele, absent

or reduced frontal bones and absent parietal bones) were seen when

Imatinib was administered during organogenesis at 100mg/kg

(corresponding to 1000 mg in humans), while, at higher dosages, total

fetal loss was seen in all animals. Fetal loss was not observed at

dosages <=30 mg (Novartis: Imatinib investigator brochure).

Nilotinib:

As reported with Imatinib, genotoxicity studies in bacterial in vitro

and in vivo mammalian systems did not reveal evidences for a mutagenic

potential of Nilotinib.

In pharmacokinetic distribution studies in rats at dosages up to

180mg/kg per day, Nilotinib showed minimal brain and testis

penetration. A significant decrease in total epididymal weight was

observed at the maximum dose level, while all other male reproductive

parameters, including sperm count and sperm motility, were unaffected.

Reproductive and developmental studies have been completed in rats and

rabbit. No effects on fertility were noticed in males or females rats,

while at doses >20mg/kg/d the embryos died. Compared to

Imatinib, no

evidence of teratogenicity in rabbits or rats was seen, while the drug

was embryo- and fetotoxic in rats and rabbits at dosage producing

maternal toxicity. The oral administration of Nilotinib in female rats

from d6 gestation to d21 post-partum resulted in only maternal effects,

as observed after longer gestational period, reduced food consumption

and lower body weight gain at 60mg/kg. The maternal dose of 60mg was

also associated with decreased pup body weight and changes in some

minor physical, developmental parameters (earlier tooth eruptions and

eye opening).

Following a single dose of 20 mg/kg oral dose of C14 Nilotinib in

pregnant rats, the higher tissue concentration compared to blood were

observed in the maternal liver, kidney, uterus heart and amnion. In the

fetus, the tissue concentration was lower than that observed in the

maternal organs, except for the liver, which had 1.6 fold higher

levels. After oral daily dosing between 30 and 100 mg/kg, Nilotinib

concentration was below the limit of quantification in rabbit’s

fetuses, while in the group treated with 300mg/kg; fetus concentration

was only 8% of the maternal serum, indicating a low absorption of

Nilotinib in the fetus. The transfer of drug and metabolites to milk

was observed following an oral dose of C14 Nilotinb to lactating rats.

It is estimated that, in 1L of human milk, the infant can be exposed to

0.26% of a 400mg adult dose. (Novartis: Nilotinib investigator brochure)

Dasatinib:

Dasatinib did not appear to affect fertility in male rats at dosage

<10 mg/kg/day and was not toxic to the offspring at these doses,

while effects included reduced size and secretion of seminal vesicles

and testis and an immature prostate.

In female rats, Dasatinib was observed to be teratogenic, extensively

distributed in maternal tissues, and secreted into milk.[11]

At plasma concentrations below those observed in humans receiving

therapeutic dosage of Dasatinib, embryo-fetal toxicities were observed

in pregnant rabbit and rats. Fetal deaths were observed in rats. In

both rats and rabbits, the lowest doses of Dasatinib tested resulted in

embryo-fetal toxicities. These doses produced maternal AUCs 0.3 fold

the human AUC in females at dose of 70 mg twice daily, and 0.1 fold the

human AUC in rats and rabbits. Embryo-fetal toxicities included

skeletal malformations at multiple sites (scapula and all long bones,

including ribs), reduced ossification, generalized oedema and

microhepatia. (Dasatinib Investigator Brochure; Sprycel® (Dasatinib)

tablets, Summary of Product Characteristics).

It is not known whether Dasatinib is excreted in human milk.

Other

TKIs:

Little is known concerning the recently approved Bosutinib (Bosulif,

Pfizer) and Ponatinib (Iclusig, Aria Pharma), although for both of them

preclinical studies of mutagenesis seem to be negative, and

teratogenity is similar to the other described TKIs with effects on

osteogenesis and vasculogenesis.

TKIs in Pregnancies and Conception

Imatinib

in man:

Since the first reports of unplanned conception in male taking Imatinib

at standard and higher dosages, no increased risk of congenital

malformations or increased abortion have been reported.[12-14]

In a series of female and male patients treated with Imatinib, Ault et

al[15] described 8 male patients

who conceived, with an exposure of 18

months (range 4-48 months) to Imatinib. Taking into consideration the

72 days for male gonads to come to maturation, the majority of those

patients have been fully exposed to the drug at conception. In those 8

patients, conception resulted in the birth of 8 babies (1 spontaneous

abortion and one twin pregnancy). One of those babies was born with a

mild malrotation of the small intestine, surgically fixed. No problems

were observed after the birth in terms of growth and development in 38

months follow up.

More than 150 cases have been described so far and except for the

malrotation of the intestine reported earlier and one stillbirth with

malformations in the previous series, the other pregnancies/deliveries

resulted uneventfully.

Imatinib

in women: Completely different is the outcome when the

woman is taking Imatinib, and the embryo-fetus is exposed to the drug.

Different reports have been published in the past years reporting

patients treated with Imatinib who conceived and or became pregnant

during therapy. In the series of Ault et al., together with the 8 male

patients, 10 female were presented (1 in CCR, 1 in accelerated phase

and 8 in an advanced phase of the disease) who received Imatinib at

standard dose (9 patients) or 800mg (1 patient) until pregnancy was

identified, with exposure between 4 and 9 weeks. Two patients had a

spontaneous abortion after discontinuation of Imatinib, while one

patient had a therapeutic abortion. The remaining seven pregnancies

were carried to term resulting in the birth of 8 babies (twin girls).

One baby had a hypospadias that was surgically corrected, while the

remaining 7 were healthy and presented with a normal growth and

development after 53 month follow up.

The first systematic review of pregnancies was reported by Pye et

al,[16] who collected information

from different Institutions,

describing 180 women exposed to Imatinib during pregnancy. Of these

pregnancies, outcome data are available for only 125 (69%). Women were

exposed to Imatinib during all pregnancy (38 patients), during 1st trimester

(103 patients), during both 1st

and 2nd

trimester (4 patients) or after the 1st

trimester (4 patients). Of those with known outcomes, 50% delivered

normal infants and 28% underwent elective terminations, 3 following the

identification of abnormalities. Of 12 infants with abnormalities

identified in carried pregnancies, 8 were live births, 1 stillbirth,

and 3 terminations. A total of 10 of the 12 infants with abnormalities

have been exposed to Imatinib during the first trimester (information

unavailable for the remaining 2 infants). Because of both tyrosine

kinases and bcr-abl inhibition by Imatinib, it is conceivable that the

congenital abnormalities result from inhibition of members of this

extensive family. Furthermore, the abnormalities evidenced were similar

to those observed in preclinical studies (exencephaly, encephalopathies

and abnormalities of the skull bones observed in the rodent studies).

Recently, more attention is given to the possibility of a

planned/unplanned pregnancy in CML patients of both sexes. The majority

of the events described, including 2 cases from our institution

(unpublished data), are carefully followed, pregnancies are possibly

planned, and Imatinib interrupted early or right before conception, so

all of the pregnancies resulted in normal babies. The behavior of both

physicians and patients may be different in other Countries where

discontinuation of the drug is not systematic, and most of the

pregnancies were not even reported to the hematologist when

discovered.[18-19] Of the 28

pregnancies from 21 female patients in

remission reported by the Pakistan group, 27 assumed Imatinib. Of the

27 exposed pregnancies, 6 were exposed during 1st

trimester (wks 6-12),

12 during 1st

and 3rd,[14-31] and 9

throughout the pregnancy until delivery. One stillbirth presented with

congenital malformations and one baby died without malformations after

one week after an apparently uneventful pregnancy. In this series, the

authors reported as adverse event 2 babies born prematurely with low

birth weight. Finally, three spontaneous abortion and 3 elective

abortions were recorded.

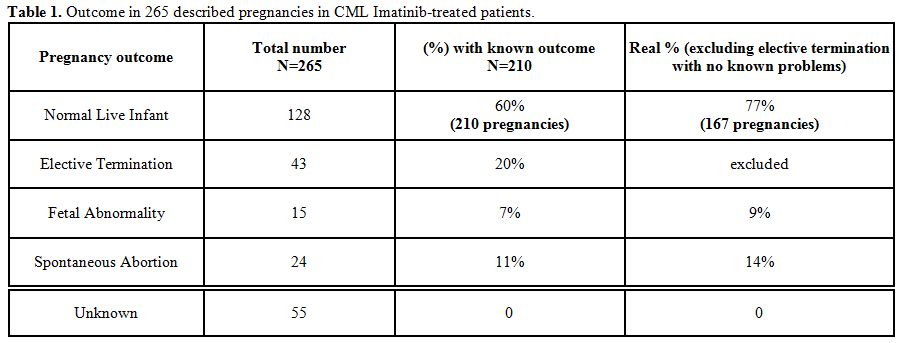

Table 1

summarizes 167 of

a total 210 Imatinib female pregnancies published and/or observed in

our Institution with sufficient data and follow up. Within those 167

pregnancies, 128 were uneventful (77%), while 24 ended in spontaneous

abortion (14%), a percentage slightly higher compared to the normal

population (10-12%).[17]

Fifteen/167 (9%) presented with abnormalities,

including one referred to a concomitant drug (warfarin syndrome). All

patients in this group were exposed to Imatinib during organogenesis

(>5wk gestation).

| Table 1. Outcome in 265 described pregnancies in CML Imatinib-treated patients. |

Finally, although

most pregnancies exposed to Imatinib may have a

successful outcome, a significant proportion of drug-related serious

fetal malformations and a slightly higher risk of spontaneous abortion

remain at risk. For this reason, pregnancy should not be avoided, but

planned.

Nilotinib

in men:

Little is reported regarding conception during Nilotinib treatment. One

case from our Institute (unpublished data) regards a 33 years male

patient with CML enrolled in the GIMEMA NILIM trial (alternated

Nilotinib/Imatinib), who wanted to conceive his 2nd

child. He discussed the opportunity to delay therapy but, taking into

consideration the 72 days necessary to complete gonads maturation

process in male, we suggested conceiving in the first two months on

Nilotinib therapy. He conceived after 40 days and had a healthy boy

born at term. He is now 5 years old, regularly growing and healthy.

The investigator brochure, ed.8 (June 2012) refers to a total of 36

cases of drug exposure via the father. One of these cases presented

with fetal abnormalities ended in a therapeutic abortion.

Nilotinib

in woman:

As for men, very little is reported for women getting pregnant while

exposed to Nilotinib. Two cases were published and indexed, and one

more case was reported by an Italian institution. The firstly published

case regards a 30-year-old woman with chronic myeloid leukemia who

became pregnant twice successfully. Philadelphia-positive CML in its

chronic phase was diagnosed at 16 weeks of her first gestation and

received no treatment throughout her pregnancy. At 38 weeks of

gestation, a normal infant was delivered by cesarean section. Two years

later, while, in major molecular response (MMR) on Nilotinib 200 mg

bid, she became pregnant again. The unplanned pregnancy was identified

during her first trimester of gestation after the patient had

experienced 7.4 weeks of amenorrhea. The patient was informed of the

potential fetal toxicities of therapy, but decided to carry on her

pregnancy. Nilotinib was stopped, and no further treatment was given

until delivery. A follow-up with ultrasound scans during the course of

the pregnancy was unremarkable. At gestational week 33, she delivered

via cesarean section a healthy male baby weighing 3.2 kg. He was

breast-fed for 2 months and at 5 months post-partum, the child was

healthy and normally developing.[20]

The second case was reported by the French intergroup of CML.[21] It regarded a 38 years female who

got her 5th

pregnancy while on Nilotinib. Treatment was stopped when pregnancy was

discovered, and replaced by Interpheron-a. Three months ultrasound

showed a big omphalocele ending into the pregnancy interruption.

The other case, unpublished, was reported in Italy: a 41 years female

resistant to Imatinib, switched to Nilotinib 400 bid, achieving MMR

after 3 months, and complete molecular remission (CMR) with bcr-abl

transcript undetectable at 9 months. After 11 months she became

pregnant. Fetus was exposed for 5 weeks before stopping therapy. The

pregnancy was unremarkable. She lost CMR, but PCR stayed <0.19%

IS

until delivering a healthy baby girl.

In the Nilotinib investigator’s brochure, 45 cases have been reported

of drug exposure during pregnancy. There was only one case with fetal

abnormalities (probably the same already described by the French

group). In addition, there was one female exposed pregnant of twins

with one twin experiencing congenital transposition of great vessels

resulting in death, and the other twin experiencing a non-serious heart

murmur.

Dasatinib

in men:

Cortes et al evaluated the effect of Dasatinib on pregnant partners of

9 male patients who conceived children while receiving Dasatinib (22).

Normal newborns were reported in 7 cases, with the outcome of the other

cases unknown. All male patients remained on treatment during and after

the pregnancies. In 1 case, the mother experienced pre-eclampsia but

delivered a healthy newborn at 37 weeks, without birth defects or

neonatal complications.

Dasatinib

in woman.

Published information regarding the use of Dasatinib in pregnancy is

limited to 17 cases describing the outcome of female patients with CML,

who became pregnant while receiving Dasatinib. In all but 1 case,

Dasatinib was stopped upon confirmation of pregnancy in patients

electing to give birth. Data from 16 patients with CML enrolled in

phase 1 to 3 Dasatinib clinical trials and 6 voluntarily submitted

reports were used to complete the study described by Cortes et al..[22]

A total of 13 pregnant female patients were identified: of these, 1

patient gave birth to a normal newborn, 1 to a premature newborn, 4 had

induced abortions, 2 had spontaneous abortions and 5 were pregnant at

last reported follow-up. The normal infant was born to a 36-year-old

female patient with CML in chronic phase (CP). Pregnancy was identified

after 7 weeks of gestation when the patient was under treatment with 70

mg of Dasatinib twice daily. The premature infant was born to a

29-year-old female patient with CML in accelerated phase treated with

Dasatinib 70 mg twice daily; he was delivered by caesarian section

after 7 months' gestation, was “small for dates” but had no defects.

Kroll et al[23] reported the use

of Dasatinib in a 23-year-old female

patient with CP-CML, who became pregnant while undergoing treatment.

When pregnancy was identified after approximately 5 weeks of gestation,

she was being treated with Dasatinib 70 mg once daily and was in CCR.

Treatment was discontinued immediately. While the patient was closely

monitored and off therapy, she developed leukocytosis and a mild

thrombocytosis. Subsequently, she was given hydroxyurea, but developed

progressive leukocytosis and increased levels of lactic dehydrogenase

levels. Cytarabine was administered to reduce the white blood cells

(WBC) count to normal within several days. To avoid further fetal

exposure to chemotherapy and resume more definitive therapy for the

mother’s CML, doctors induced labor at 35 weeks. The patient delivered

a healthy female baby without any developmental delay or structural and

functional anomalies. Three days post delivery, Dasatinib 70 mg daily

was restarted concurrently with a 2-week hydroxyurea tapering. She

reached CCR in the peripheral blood 5 months after re-initiating

Dasatinib.

Conchon et al[24] reported the use

of Dasatinib in a 25-year-old female

patient with CP-CML, who became pregnant while undergoing treatment

with 70 mg twice daily. Pregnancy was identified during the first

trimester, while she was in hematologic remission and Dasatinib was

discontinued immediately. Hematologic relapse occurred, and the patient

was, therefore, treated with INF-α (although complete hematologic

response was not achieved). The patient delivered a male baby at 33

weeks with no sequelae or malformations. A few days following delivery,

the patient was treated with hydroxyurea for 4 months, and then

restarted TKI.

Berveiller et al[25] reported a

23-year-old woman with CML, who became

pregnant after the switch to Dasatinib following Imatinib failure. When

pregnancy was identified at 9 weeks of gestation, she was treated with

Dasatinib 100 mg once daily for 4 weeks achieving complete hematologic

response. Dasatinib was not discontinued due to the high-risk

characteristics of the patient, and an obstetric ultrasonography at 16

weeks of gestation revealed a fetal hydrops with subcutaneous edema,

pleural effusion, and ascites. Pregnancy was terminated due to the poor

perinatal prognosis after 17 weeks of gestation. The patient delivered

a eutrophic male fetus with no organ malformations except for

microretrognathia and hypertelorism. Fetal karyotype was also normal.

Fetopathologic examination revealed a subcutaneous edema in the nuchal

and dorsal regions. Transplacental transfer of Dasatinib was observed

with drug concentrations of 4 ng/mL in maternal plasma, 3 ng/mL in

fetal plasma, and 2 ng/mL in amniotic fluid.

Bayraktar et al[26] reported a

normal pregnancy outcome of a

25-year-old patient with CML, who was treated with Dasatinib 100 mg

once daily for the first 6 weeks of gestation. Once the pregnancy was

confirmed, Dasatinib was stopped, and the patient was managed

conservatively with close observation of her disease. During her

pregnancy, hematologic relapse occurred with mild leukocytosis and

thrombocytosis that did not require treatment. The infant was delivered

at 37 weeks without any documented birth defects. The patient was

restarted on Dasatinib 100 mg daily shortly after her delivery and did

not breastfeed. At 2 years’ follow-up post delivery, the patient had

molecular remission and her daughter met all developmental milestones.

Other

TKIs:

As far as we know, no conception/pregnancies were described while

taking Bosutinib or Ponatinib. In our Institution, we followed a male

patient diagnosed with CML and enrolled in a Bosutinib trial that

cryopreserved his sperm before starting therapy and conceived with an

intra-uterine insemination (IUI) a healthy baby girl who is now 3 years

old and normally developing.

Discussion

Imatinib and the subsequent second and third generation TKIs has

represented and represents, a major advance leading to a successful

targeted therapy with substantial improvement of survival and quality

of life in CML patients.

Considering the significant proportion of female/male patients

diagnosed with CML in reproductive age, and the substantial normal

lifespan of those patients when treated and responding, it became

mandatory to address issues relating to fertility and pregnancy. The

management of fertility begins at diagnosis. In fact, the patient in

reproductive age should be informed about the risk of unplanned

pregnancies in terms of fetal problems and/or the risk of uncontrolled

disease in the case of stopping therapy, but also on the possibility

that a controlled pregnancy can be carried out when the treatment has

being started, and the response is optimal.

There are no consensus/guidelines regarding the best behaviour in case

of pregnancy.

While it seems that there are no problems in terms of fertility,

conception and delivery of female partners of male patients (even if

for newer TKIs not enough data are available), female patients should

not be exposed to TKIs during pregnancy.

Based on the published data, 10-20% of maternal exposure during the 1st

trimester to TKIs ends in fetal problems or spontaneous abortion. The

problems consist mainly in skeletal malformations, soft tissue

abnormalities (especially involving the vessels and organs formation)

and small for date babies, and are similar to the one described in

animal studies.[27]

An independent algorithm by Kumar et al. for the management of CML

during pregnancy recommended discontinuation of TKIs. If patients are

in the first or second trimester, interferon alpha (IFN-α) can be

given; leukapheresis can regulate white blood cell (WBC) counts as

required and hydroxyurea considered for patients not responding to

IFN-α. Patients in their third trimester and not responding to IFN-α or

hydroxyurea can be treated with Imatinib, and if still not responding,

with second generation TKIs.[28]

Shapira et al suggested an algorithm in which pregnancies discovered at

diagnosis should be considered for Imatinib treatment only if

unresponsive to IFN-α and, possibly, after 1st trimester.[29]

Imatinib is a compound that highly binds to plasma proteins and has a

high molecular weight that should limit placental transfer. Two studies

addressed the possibility to administer Imatinib later in the course of

pregnancy, evaluating the concentration of this drug and its active

metabolites in the different maternal/fetus compartments. In two cases

presented by Russell at al, Imatinib appears to cross the human

placenta poorly. In two pregnancies taking Imatinib during the 3rd

trimester, concentration of drug and his metabolite CGP74588 was

measured at delivery in maternal blood, placenta, and cord blood.

Little or no drug was found in the cord blood, while it was present at

high concentration in maternal blood and placental tissue, confirming

this hypothesis.[30] In a

different pregnancy with exposure from 21st

to 39th

week of gestation, Imatinib was present at 338ng/mL in the cord blood

and 478 ng/mL in the peripheral blood infant (1/3 range) vs 1562 ng/mL

in maternal blood.[31]

In contrast, an high concentration of drug was found in breast milk in

both studies, as confirmed in other works and described in animal

models.[32]

These reports suggest that in a male patient taking Imatinib or

Nilotinib, no particular risks of fertility; conception or pregnancy

have been evidenced. Caution should be used when patient is taking

Dasatinib, due to the very few data available. No reports are available

for patients taking Bosutinib or Ponatinib. For those patients, the

possibility to cryopreserve sperm before starting therapy should be

discussed.

In a female patient, in reproductive age, effective contraception

should be suggested at diagnosis. A pregnancy should be planned only

after the milestone of a stable MMR (or better, e.g. >MR4.5)

reached

more than 18-24 months earlier. Ob-gyn visit for pre-conception tests

(including in some cases male sperm evaluation), ultrasound and planned

conception is highly recommended.

Therapy should be stopped immediately before or soon after conception.

All drugs must be avoided during the organogenesis (post menstrual days

31-71, weeks 5-13), Q-PCR must be monitored each month/2 months to

follow the transcript. Therapy should be considered only if a

cytogenetic or hematologic relapse occurs.[33]

Each single patient

should be individually evaluated taking into account the rapidity of

the relapse, the clinical CML history, and most of all, the pregnancy

status (weeks of gestation).

Interferon can be considered safe throughout pregnancy[34]

and

hydroxyurea can be used to control leucocytosis after

organogenesis.[35] When necessary,

TKIs therapy with Imatinib or

Nilotinib could be considered after placenta has been formed and

organogenesis completed,[36]

although high Nilotinib concentration has

been found in fetal liver, in animal models. Dasatinib, on the

contrary, seems to pass the barrier and should be avoided.

All patients can breast feed the first 2-5 days postpartum to give the

baby the colostrum. Newborns have very immature digestive systems, and

colostrum delivers its nutrients in a very concentrated low-volume

form. It has a mild laxative effect, encouraging the passing of the

baby's first stool; that helps to clear excess bilirubin, contains

immune cells and many antibodies, immune substances and a series of

cytokines and growth factor.[37]

Considering the few days of delay to

resume treatment, it could be important for the newborn to access this.

After delivery and providing a good molecular transcript, therapy can

be postponed to consent full breast feeding, according to the

haematologist judgement.

All cases with good control of the illness at conception and a good

response to a specific TKI stopped during pregnancy and resumed after

delivery, have re-reached MMR within 3-6 months, confirming the

possibility of a safe therapy manipulation during pregnancy.[38-40]

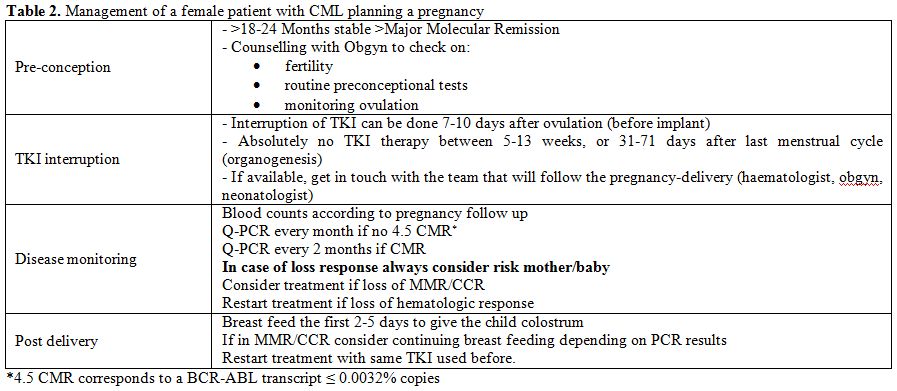

In conclusion, we can resume all those informations updating a table

earlier presented by Apperly (Table

2).

It is important to take into consideration that each case should be

considered as a single case in which many factors may play a crucial

role: the biology of the illness, the response to treatment, the

outcome during the pregnancy, and the willing of the patient should be

clearly considered and discussed.[41-42]

| Table 2. Management of a female patient with CML planning a pregnancy. |

In our Institution,

we have a team composed by haematologists,

urologists, ob-gyn and neonatologists, that work together during the

planning, the conception, the pregnancy, the delivery and the immediate

post-delivery, to assure the best care to mother and child. We have

followed 3 CML female conception/pregnancies and 6 male conceptions,

all with normal children (1 female patient pregnancy is ongoing) plus

many pregnancies of patients affected by lymphomas or acute leukemia.

The preservation of fertility is part of our routine when a female/male

patient is diagnosed as having a hematologic problem needing therapy.

Through the GIMEMA CML working party, there is an ongoing observational

retrospective and prospective multicenter study to register all female

pregnancies/male conception in TKIs era and a similar registry is in

preparation through the European Leukemia Network of CML Working Party,

coordinated by Italy and Russia. We hope that an extensive report of

such events will help in managing the possibility to conceive in CML

patients in order to give our patients not only a normal lifespan, but

also a normal life.

Acknowledgements

To my daughters Flavia and Valeria.

References

[TOP]