Received: April 28, 2014

Accepted: May 16, 2014

Meditterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014041, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.041

This article is available on PDF format at:

Francesca Rinaldi1*, Raffaella Lissandrin1*, Francesco Mojoli2, Fausto Baldanti3, Enrico Brunetti1, Michela Pascarella4 and Maria Teresa Giordani5

1

Department of

Infectious Diseases, IRCCS San Matteo Hospital Foundation, University

of Pavia, Viale Golgi 19, 27100 Pavia, Italy.

2 Clinical-Surgical, Diagnostic and Pediatric

Sciences

Department, Section of Anesthesia and Intensive Care 1, University of

Pavia, IRCCS San Matteo Hospital Foundation, Viale Golgi 19, 27100

Pavia, Italy.

3 Molecular Virology Unit, Virology and

Microbiology

Department, IRCCS San Matteo Hospital Foundation, Viale Golgi 19, 27100

Pavia, Italy.

4 Microbiology Service, San Bortolo Hospital,

Viale

Rodolfi 37, 36100 Vicenza, Italy.

5 Infectious and Tropical Diseases Unit, San

Bortolo

Hospital, Viale Rodolfi 37, 36100Vicenza, Italy.

* These authors contributed equally to the work

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Acute

Human Cytomegalovirus

(HCMV) infection is an unusual cause of venous thromboembolism, a

potentially life-threatening condition. Thrombus formation can occur at

the onset of the disease or later during the recovery and may also

occur in the absence of acute HCMV hepatitis. It is likely due to both

vascular endothelium damage caused by HCMV and impairment of the

clotting balance caused by the virus itself. Here we report on two

immunocompetent women with splanchnic thrombosis that occurred during

the course of acute HCMV infection. Although the prevalence of venous

thrombosis in patients with acute HCMV infection is unknown, physicians

should be aware of its occurrence, particularly in immunocompetent

patients presenting with fever and unexplained abdominal pain.

|

Introduction

Acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is

clinically

relevant condition usually associated with bowel ischemia caused by the

involvement of superior mesenteric and splenic veins. In the general

population, the prevalence of PVT is about 1% but can reach 16-40% in

patients with cirrhosis or cancer.[1]

In more than 70%

of cases, PVT is associated with local factors, such as cirrhosis,

malignancy, intra-abdominal infection, abdominal surgery, trauma or

liver transplantation. Moreover, up to 72% of presumed idiopathic PVT

may be associated with thrombophilic conditions and hematologic

diseases.[2] PVT has been described

in patients with

acute hepatitis caused by EBV, HAV, HBV, HCV, but it has been more

often associated with acute HCMV hepatitis.[3]

In this

report, we describe two cases of acute PVT associated with an HCMV

acute infection in two adult immunocompetent women.

Case One

A 62-year-old female was admitted to San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza,

Italy, in September 2011, with fever and abdominal pain lasting for

several weeks. The patient’s and family history were unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed only slight discomfort on palpation of

the epigastric area. Liver and spleen were regular in size.

White blood count (WBC) was 11.7 x103/μL,

60% lymphocytes, and liver

function tests (LFT) were abnormal (AST 333 IU/mL, ALT 433 IU/mL

[normal value <37], GGT 296 IU/mL [n.v. <33], alkaline

phosphatase (ALP) 221 IU/L [normal range 30-105], bilirubin 1.0 mg/dL

[n.v. <1.3]), some inflammatory indices were raised (C-reactive

Protein 3.65 mg/L [n.r 0.00-0.50], ferritin 1442 ng/mL [n.r. 10-160 ],

lactate dehydrogenase 1098 U/L [n.r. 200-420], creatine phosphokinase

24 U/L [n.r. <200] procalcitonin 0.54 ng/mL [n.v.<0.5],

with

normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 27 mm/h [n.r. 2-45]).

Chest X-Ray was negative. An abdominal ultrasound (US) (Aplio XG Model

SSA-790A, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan), showed a complete thrombosis of the

left portal branch, confirmed by a contrast-enhanced ultrasound

(SonoVue, Bracco, the Netherlands) and a computed tomography (CT) scan

(see Figure 1,

Panel 1a).

No other lesions were

found in the abdomen. A hematologic evaluation ruled out

myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders; although a

bone-marrow biopsy was not considered, an immune-phenotypic analysis of

the peripheral white blood cells and red blood cells resulted

in

normal range and did not find cellular clones with GPI-linked molecules

deficit (in order to exclude paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria).

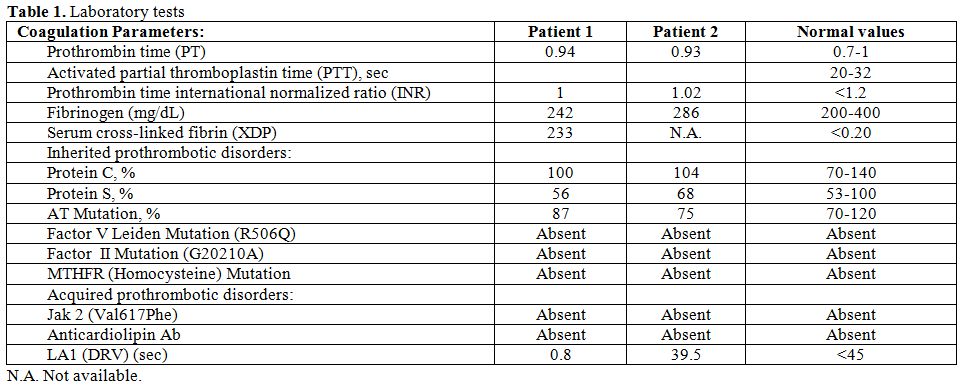

Inherited and acquired risk factors for thrombosis were ruled out (see Table 1). The

patient was a mild

smoker (5 cigarettes/day) and was not on hormones; neoplastic markers

(Carcinoembryonic [CEA] and carbohydrate antigen [Ca]19.9 and 15.3,

alpha-fetoprotein [AFP]) were all negative. Antibodies against the main

hepatotropic viruses (HAV, HBV, HCV, HEV) were negative while HCMV

serology suggested primary infection (IgM 10.86 mg/dL [negative

<1],

IgG 12.8 mg/dL [negative<11]). HCMV DNA (real-time PCR, Real

Time

Alert QPCR, Elitech Group Nanogen, Milan, Italy) was positive at 3434

copies/ml (sensitivity cut-off: >1111). Thus, acute HCMV

hepatitis

complicated with portal vein thrombosis was hypothesized.

The patient was treated with i.v. gancyclovir (5 mg/Kg/bid) and low

molecular weight heparin (sodium enoxaparin 4.000 U.I. bid) for 15

days. On discharge, HCMV DNA was undetectable. An abdominal US

performed before discharge showed thrombus organization (retraction and

hyperechoic clot) (see Figure

1, Panels

1b and 1c). The

patient continued oral anticoagulant treatment (Warfarin 5 mg/day with

INR check every 2-3 days in the first two weeks) for 21 months after

discharge until her abdominal US showed an almost complete

re-canalization of the left portal branch. A prolonged follow-up (40

months) including clinical interview, abdominal ultrasound, blood and

LFT resulted normal.

Case Two

A 20-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted to Maggiore Hospital in

Crema, Italy, in November 2011, for gastric pain and headache lasting

three days. A US scan of the upper abdomen (Esaote myLab25, Esaote,

Genova, Italy) showed portal thrombosis of the intra-hepatic right and

left branches, splenomegaly and free fluid in the perihepatic area and

in the Douglas pouch. Chest X-Ray was negative. Biochemical examination

revealed abnormal liver function tests: (AST 162 IU/ml, ALT 243 IU/mL,

GGT 167 IU/mL, ALP 402 IU/L) and increased inflammatory indices

(Lactate dehydrogenase 747 U/L, C-reactive Protein 1.5 mg/L); ESR was

normal at 23 mm/h.

The patient received anticoagulant therapy (continuous infusion of

unfractionated heparin, 18 UI/Kg/h). An abdominal CT confirmed portal

thrombosis involving the left and the right intra-hepatic branches and

the superior and inferior mesenteric veins. A 3 cm long thrombus was

identified at the beginning of the splenic vein, which was still

patent. The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care (ICU) of San

Matteo Hospital, Pavia, Unit where blood tests confirmed abnormal liver

enzymes with normal white blood cells (WBC: 4100/mm3, 63% of

lymphocytes). At ICU admission, a new CT scan confirmed the thrombosis

(see Figure 1,

Panel 1d)

and showed also

pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions.

Thrombophilic conditions were ruled out by specific tests (see Table 1). The

patient did not smoke

and was not on hormones.

Lymphocyte immunophenotyping was consistent with acute viral illness

(CD4/CD8 0.5, CD4: 31.1%, CD8: 57.8%). Serology revealed acute HCMV

infection: IgM anti CMV (ELISA): 11.8 (negative < 0.9, positive

>

1.1), IgG avidity test (ELISA): 18%, (low < 35, high

>50). HCMV

DNA (real-time PCR) was positive 100 copies/ml (cut-off >100

copies). Serology for HIV, HCV, HBV, S.typhi, Yersinia spp, Hantavirus,

Listeria spp, Leptospira spp, Borrelia spp and HSV-8 were negative.

Neoplastic markers (CEA, Ca 19.9 and Ca15.3, AFP) were all negative.

She was treated with anticoagulants (unfractionated heparin followed by

enoxaparin 100 UI/Kg), with progressive regression of the thrombosis

and disappearance of the fluid collections. A US scan one month after

discharge showed further regression of PVT.

| Table 1. Laboratory tests |

Discussion

Although HCMV infection is very common, up to 40% of adult

immunocompetent subjects are seronegative for HCMV. The prevalence of

HCMV infection is underestimated, since it occurs in childhood when it

is usually asymptomatic. In the adult it is frequently characterized by

fever, swollen neck lymph nodes and mild hepatitis, spleen enlargement

and low platelet count. The true rate of symptomatic disease is,

however, unknown. The diagnosis is commonly made by serology (IgM

anti-CMV positivity and rising title of IgG anti-CMV).

HCMV reactivation is commonly seen in immunocompromised individuals

such as transplant and AIDS patients, leukemia and lymphomas, or in

situations such as prolonged steroids administration for rheumatologic

and autoimmune diseases. Portal thrombosis is an uncommon but not so

rare event occurring during acute HCMV infection and has been recently

sporadically documented.[4,5]

Atzmony and Abgueguen in

2010 reported a prevalence of thrombosis among hospitalized patients

with acute HCMV infection of about 6.4% and 7.9% respectively, while

Justo et al. reported a 1.9-9.1% incidence of HCMV infection in

patients with thrombotic events.[6,7,4]

HCMV-related thrombosis can occur also several weeks after the

diagnosis of acute HCMV.[7]

Unlike other HCMV lesions, which differ in immunocompetent and

immunocompromised patients, deep venous thrombosis seems to occur in

both categories of patients,[8] but

with different

localization. Justo et al. in 2011 showed how immunocompetent patients

experienced more splanchnic vein thrombosis while HIV immunocompromised

ones are more susceptible to deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary

embolism during highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART).[4]

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain HCMV-induced vascular

thrombosis, including a direct action by HCMV itself and the activation

of different molecules. HCMV could directly invade the endothelial

cells, causing endothelial damage and the activation of coagulation

factors.[9] It could also

facilitate thrombin

production and interrupt the synthesis of prostaglandin and

interleukin-2 due to procoagulant phospholipids on its surface. Both

these mechanisms cause platelet adhesion.[9]

HCMV, like other viruses and bacteria, seem to induce the production of

anti-phospholipid antibodies[10]

and can inhibit

P53-mediated apoptosis through the activation of its first gene

transcribed, IE84, which binds P53 and inhibits its transcriptional

activity.[7]

Predisposition to thrombosis can be linked to different clinical

situations, such as the use of oral contraceptives, surgery, pregnancy,

active malignancy (directly or as part of paraneoplastic syndrome), and

protracted immobility.[4,11] All

these factors seem to be prevalent in immunocompetent patients.[4] In hematological disorders, causes of

vein thrombosis

are transient or permanent antiphospholipid syndrome, factor V Leiden

heterozygote mutation, protein C or protein S deficiency. In a recent

literature review, chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are

associated in 6-33% of patients with portal vein thrombosis.[2] In the review, the JAK2 V617F somatic

mutation was

reported both in overt and non-overt MPN.[2]

Coagulation factors defects and myeloproliferative disorders, including

JAK2 V617F somatic mutation had been ruled out in both cases (see Table 1).

The clinical manifestations of acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT)

depend on the extent of the obstruction and the speed of its

development. The consequences of an untreated PVT depend on the same

factors: if portal flow is suddenly interrupted (as happens in

experimental thrombosis) a liver infarction or an ischemia of the bowel

may follow.

Even incomplete thrombosis can alter intestinal permeability and lead

to bacterial sepsis, enteric bleeding or diarrhea. In the absence of

treatment, thrombus organization can lead to chronic thrombosis and

portal cavernoma.

When PVT occurs, anticoagulation therapy for at least 3 months is

recommended, starting with low molecular weight heparin in order to

achieve rapid anticoagulation and shifting to oral anticoagulation as

soon as the patient’s condition has stabilized. Long-term

anticoagulation therapy in patients with acute PVT and permanent

thrombotic risk factors that are not otherwise correctable is

recommended.[11]

Antiviral treatment is mandatory in immunocompromised patients, while

its administration in immunocompetent patients is debatable. In case

one, HCMV-DNA tested positive, and the clinician decided to treat the

patient with gancyclovir. Moreover, the initial suspicion of an

associate neoplasm or a hematological malignance played a role in this

decision. In case two the viremia was borderline due to the immune

system control, so in spite of the more aggressive presentation, virus

infection was left untreated.

Finally, bedside US (or “point of care US”) may prove to be a

life-saving approach in emergency settings; a protocol finalized to

achieve a prompt diagnosis of the thrombotic events can be easily

learned by physicians with no previous experience in US.[12]

In our experience, bedside abdominal US can help recognize portal vein

thrombosis due to infectious agents like HCMV and avoid its dangerous

consequences.

Conclusions

Physicians should consider hematologic, neoplastic and infectious etiologies in the workup of patients with fever and PVT. Although venous thrombosis during acute HCMV infection is uncommon in immunocompetent patients, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion, and testing for HCMV IgM in these cases is recommended.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sam Goblirsch, MD, for reviewing the manuscript and Dr. Carlo Scolarin, MD, for providing patient informations.

References

[TOP]