Received: February 11, 2014

Accepted: May 30, 2014

Meditterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014045, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.045

This article is available on PDF format at:

AR. Nateghian¹, JL. Robinson², P. Vosough³, M. Navidinia4, M. Malekan4, A. Mehrvar, B. Sobouti3, P. Bahadoran5 and Z. Gholinejad4

1

Department of Pediatrics, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran,

Iran.

2 Department of Pediatrics , University of

Alberta and Stollery Children's Hospital. Edmonton, Canada.

3 Mahak Hospital and Rehabilitation Complex,

Tehran, Iran.

4 Pediatric Infections Research Center, Mofid

Children Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences,

Tehran, Iran.

5 Aliasghar Children’s Hospital, Iran University

of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Background.

Infection in pediatric cancer patients has become a concerning problem

due to increasing antimicrobial resistance. The goal of this study was

to determine the antimicrobial resistance patterns of blood isolates

from pediatric oncology patients in Iran to determine if there was

significant resistance to quinolones

Methods. Children with cancer who were admitted with or developed fever during admission to Aliasghar Children’s Hospital or Mahak Hospitals July 2009 through June 2011 were eligible for enrollment. Two blood cultures were obtained. Antimicrobial sensitivity test was performed for ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, meropenem, cefepime, and piperacillin-tazobactam on isolates from children who were bacteremic. Results. Blood cultures were positive for 38 episodes in 169 enrolled children but 9 episodes were excluded as blood cultures were thought to be contaminated, yielding a bacteremia rate of 29/160 (18%). The mean age of children and the stage of malignancy did not differ between those with and without bacteremia. Meropenem was the most likely antibiotic to cover isolates (97%) with cefepime having the lowest coverage rate (21%). Quinolone coverage ranged from 63% to 76%. Conclusion. Quinolones may not be suitable for use as empiric therapy in febrile pediatric oncology patients in Iran. |

Introduction

Infectious

diseases are common life threatening complications in patients with

cancer, resulting in repeated admissions with considerable interruption

of treatment for the underlying malignancy.[1]

Although the mortality rate for infectious diseases has been decreasing

over recent decades, most children with febrile neutropenia are treated

as inpatients with long durations of admission.[2]

Recently, there are reports of successful outpatient management of

febrile neutropenia in children with malignancies with oral antibiotics

(typically quinolones).[3] However,

there is a

concerning increase in the rate of antimicrobial resistance both in

developed and developing countries, including quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and

Klebsiella

pneumoniae.

Therefore, the predicted efficacy of quinolones for invasive bacterial

infections in children with malignancies can be informative as these

drugs are used in this setting despite not yet being approved in

children.[3]

Aliasghar Children’s Hospital (an educational hospital affiliated with

the Tehran University of Medical Sciences) and Mahak Hospital (a

subspecialty non-profit center for children with cancer) are referral

pediatric oncology centers in Tehran. Almost all febrile pediatric

patients with cancer (with or without neutropenia) are admitted rather

than treated as outpatients as there is no consensus on when and how to

use risk assessments for selecting patients for outpatient management.[4]

The primary objective of this study was to determine the in-vitro

susceptibility for blood culture isolates in these hospitals to older

and newer quinolones and to compare this with the susceptibilities to

current candidates for intravenous monotherapy in this population.

Materials and Methods

All children with any cancer irrespective of their stage of disease

(including those who had finished chemotherapy or relapsed) who were

admitted with fever or developed fever in Aliasghar Children’s Hospital

or Mahak Hospitals from July 2009 through June 2011 were eligible for

enrollment in this descriptive prospective study. The same child could

be enrolled more than once in the study. Informed consent was obtained

from parents.

Fever was defined as a single episode of temperature above 38.5 degrees

C or at least two episodes of 38 degrees C one hour apart. For each

febrile patient, two blood cultures were collected simultaneously

before starting or changing the antibiotic therapy. Of these blood

cultures, one was sent to the hospital laboratory and processed by the

standard procedure and the other was sent to BACTEC the Pediatric

Infectious Diseases Research Center located in Mofid Children’s

Hospital and processed by BACTEC technology to improve the sensitivity.

Standard methods were used for identification of organisms. Children

who had positive blood cultures for common skin contaminants were

considered to be bacteremic only if both samples were positive for the

same microorganism. Antimicrobial sensitivity test was performed for

ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, meropenem, cefepime, and

piperacillin-tazobactam according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute (CLSI) methods using the standard disk diffusion method from

MAST Co (Mast Co, Merseyside, UK). A questionnaire was completed for

each patient on admission and data was analyzed by SPSS software

version-16 using appropriate statistical methods.

Data are presented as numbers and proportions. Continuous variables are

presented as mean and standard deviation.

Results

There were 173 febrile episodes during the period of study. Parental

consent was not obtained for 4 of these episodes. Blood cultures were

positive for 38 of the remaining 169 episodes but 9 episodes were

excluded from further analysis as only a single blood culture was

positive for a common skin contaminant, yielding a proven bacteremia

rate of 29/160 (18%). All 9 suspected contaminated blood cultures were

from BACTEC alone. For the 29 episodes of bacteremia, both blood

cultures were positive in 14 episodes and BACTEC alone in 15 episodes.

Ninety-one of these 160 cases were male (57%). The mean age of enrolled

patients was 82 months (SD=54.4). The mean age of cases with bacteremia

was 71.5 months (SD=55.6) and for those with negative blood cultures or

contaminated blood cultures was 84.3 months (SD=57.8) (P value=0.27).

Three enrolled children had two episodes of bacteremia during different

admissions. These were not thought to be relapses or recurrences as two

of the children had different organisms each time and the third child

had the same organism but with different susceptibilities.

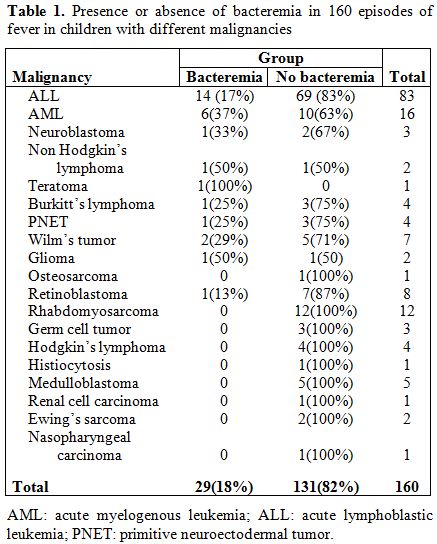

The 160 children had 19 different types of malignancies (Table 1). The types

of malignancies in enrolled patients with and without bacteremia are

shown in Table 1

(P value=0.002). Bacteremia with fever was especially common with acute

myeloid leukemia (6 of 16 episodes; 37%). There was no significant

difference in stage of malignancy between those with and without

bacteremia (P value=0.14).

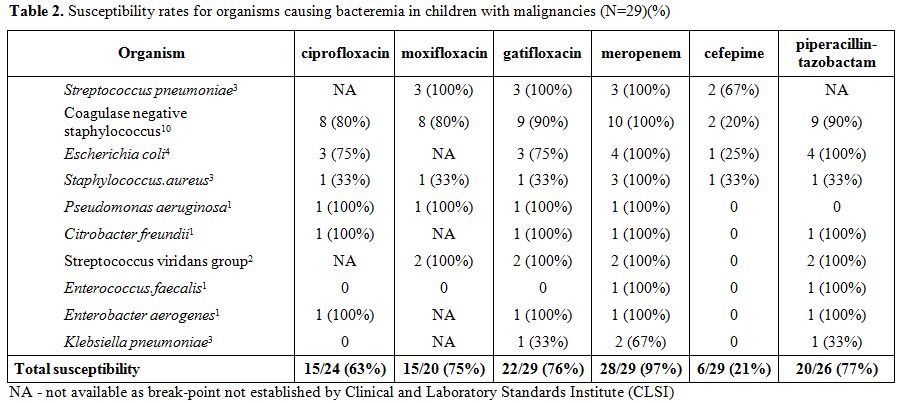

The organisms causing bacteremia are shown in Table 2 with

coagulase negative staphylococci causing 10 of the 29 cases (34%).The

coverage rate was highest for meropenem (97%) with cefepime having the

lowest coverage rate (21%). Overall susceptibility rates for the three

quinolones were very similar to each other, ranging from 63% to 76% (Table 2).

|

Table 1.

Presence or absence of bacteremia in 160 episodes of fever in children

with different malignancies. |

| Table 2. Susceptibility rates for organisms causing bacteremia in children with malignancies (N=29)(%). |

Discussion

Meropenem had the highest rate of in-vitro coverage for organisms

isolated from bacteremic children with malignancies in Iran. In

contrast, cefepime susceptibility was only about 21%, a dramatic change

from a previous study in the same population hospitals in which

susceptibility was over 80%.[5]

Only about 70% of the

isolated organisms were susceptible to quinolones with the sample size

being too small to compare ciprofloxacin to newer quinolones. Vital

gaps in quinolone coverage included Staphylococcus aureus

and Klebsiella

species.

In a 2003 study in adults in the United States with malignancies,

moxifloxacin had good coverage for gram negative organisms except for Pseudomonas species

for which it was inferior to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.[6]

In total, 78% of gram positive and 64% of gram negatives were

susceptible to moxifloxacin. The same group published a study in 2006,

showing that gatifloxacin offered good coverage for all but

methicillin-resistant S.

aureus, and Pseudomonas

and Acinetobacter species.[7] In total, 83% of gram positive and

64% of gram negatives were susceptible to gatifloxacin.[8]

International guidelines for management of children with malignancies

and febrile neutropenia were published in 2012.[9]

They describe six validated schemes for identifying children at low

risk for serious infection with it not being clear which scheme

functions best. The guidelines report that oral antibiotics (often

quinolones) appear to be equivalent to intravenous antibiotics for

empiric therapy in low-risk children. In a recent meta-analysis

specifically on the role of quinolones in children with febrile

neutropenia, 10 studies (740 episodes of febrile neutropenia, all

considered to be low-risk for poor outcomes) were included.[3]

Using varying definitions, treatment success was obtained in 83% of

those on quinolone monotherapy with there being no infection-related

mortality. This success rate appeared to be higher than that obtained

with the usual intravenous options. However, it is important to

recognize that these studies were performed in an era when quinolone

resistance was less common than in the current study. In the absence of

outcome data, it is difficult to predict what would have happened had

all low risk patients in the current study been started on quinolones,

but the high rate of in-vitro resistance is concerning.

The major limitation of the current study is that only in-vitro data

rather than clinical outcome data was available. Clinical and

Laboratory Standards Institute standards do not yet exist for all

antibiotics in this study for some of the bacteria isolated. Patients

did not have to be neutropenic to be enrolled, and those who were

neutropenic were not further classified as low-risk versus high-risk

for poor outcomes. It can be difficult to distinguish bacteremia from

contaminated blood cultures. Processing one blood culture by BACTEC

technology appeared to increase both the number of contaminated blood

cultures and the number of true positives.

Conclusions

Although quinolones appeared to be a good option for children with febrile neutropenia in other countries, one would want to be cautious given the apparent high rate of resistance in Iran. Patients who are bacteremic with pathogens of low virulence such as coagulase negative staphylococci or enterococcus are likely to survive even if empiric antibiotics do not cover that organism, but the same is not true for E. coli or Klebsiella species, both of which demonstrated significant quinolone resistance is the current study. Given the rapid emergence of multi-resistant gram negatives, it is imperative that rates of quinolone resistance be followed closely in oncology centers where febrile neutropenia is being managed with this class of drug.

Acknowledgments

We would like to remember Dr. Parvaneh Vosough, a great teacher of pediatric oncology in Iran whose efforts for Iranian children with malignancies cannot be forgotten. She passed away before this study was published. We kindly appreciate Dr. Bahram Darbandi, Dr. Shahla Ansari, Dr. Maryam Golparvar, Dr. Maryam Hoseini, and Dr Tahereh Naimi for their cooperation in data collection. This study was supported and funded by The Pediatric Infections Research Center at Mofid Children’s Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

References

[TOP]