Received: February 24, 2014

Accepted: June 16, 2014

Meditterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014048, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.048

This article is available on PDF format at:

Massimiliano Salati1, Marina Cesaretti1, Matteo Macchia1, Mufid El Mistiri2 and Massimo Federico1

1

Department of Diagnostic, Clinical and Public Health Medicine, Modena

Cancer Center, Italy.

2 Hamad Medical Corporation, National Center for

Cancer Care and Research (NCCCR), Qatar.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract The

epidemiology of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) has always been a source of

fascination to researchers due to its heterogeneous characteristics of

presentation. HL is an uncommon neoplasm of B-cell origin with an

incidence that varies significantly by age, sex, ethnicity, geographic

location and socioeconomic status. This complex pattern was also found

to be replicated among Mediterranean basin populations. HL incidence

rates progressively decreased from industrialized European countries

such as France (ASR=2.61) and Italy (ASR=2.39) to less developed

nations such as Albania (ASR=1.34) and Bosnia Herzegovina (ASR=1.1).

Regarding HL mortality we have found that countries with the lowest

incidence rates show the highest number of deaths from this cancer and

viceversa. Finally, a wide gap in terms of survival was showed across

the Mediterranean basin with survival rates ranged from 82.3% and 85.1%

among Italian men and women, to 53.3 % and 59.3% among Libyan men and

women, respectively. Factors such as the degree of socio-economic

development, the exposure to risk factors westernization-related, the

availability of diagnostic practices along with different genetic

susceptibilities to HL may explain its variation across Mediterranean

countries. Furthermore, the lack of health resources decisively

contribute to the poor prognosis recorded in less developed region. In

the future, the introduction of appropriate and accessible treatment

facilities along with an adequate number of clinical specialists in the

treatment of HL and other cancers are warranted in order to improve the

outcomes of affected patients and treat a largely curable type of

cancer in disadvantaged regions.

|

Introduction

Hodgkin

lymphoma (HL) is a lymphoid malignancy of B-cell origin which is

classified into either nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

(NLPHL) or classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) in accordance with 2008 WHO

classification. Although they have characteristics in common, these two

disease entities differ in their clinical features and behavior as well

their cellular properties i.e. morphology, immunophenotype and the

preservation or extinction of the B-cell gene expression program. CHL

accounts for 95% of all HLs and can be further subdivided into four

histological subtypes: lymphocyte-rich (LR), nodular sclerosis (NS),

mixed cellularity (MC) or lymphocyte-depleted (LD).[1]

HL is an uncommon neoplasm with an incidence that varies significantly

by age, sex, ethnicity, geographic location and socioeconomic status.

Incidence rates are higher in more developed regions and among males

and lower in Asia. In the United States, about 9,290 new HL cases are

estimated for 2013, an incidence of 2.8 per 100,000 people per year.[2]

The hallmark of HL epidemiology is its variation in occurrence by age

at diagnosis. This is represented in industrialized countries by the

well-known bimodal curve showing two peaks: the most significant for

young-adults (15-34 years of age) and the second one occurring in later

life (above the age of 50). As already reported by Cozen et al, these

peaks are composed mainly of different subtypes with the NS pathology

being predominantly represented in the earlier age peak and the MC

disease being predominant in the later age peak.[3]

Despite its relatively low incidence and its low lifetime risk, HL

accounts for 15% of all cancers in young adults with a high impact on

quality of life. Since its earliest description in the first half of

the 19th

century, HL has proved to be

a difficult form of neoplasm to understand because of its unusual

histopathological aspects i.e. its resemblance to an infectious

process, the variability of B-cell antigen expression among its

subtypes and its occurrence in childhood and young adults. The etiology

and pathogenesis of HL thus remain poorly understood.

Epidemiological studies of HL to date have elucidated only some aspects

of this heterogeneous disorder. Future studies of wider populations are

thus necessary to more fully clarify the complexity of HL. In this

review, we provide a comprehensive description of the known

epidemiological features of HL, focusing on populations in the

Mediterranean basin, and discuss the geographic, ethnic,

socio-demographic and economic factors that impinge upon these

properties. Regional comparisons of patterns and trends for HL between

and within countries were also performed in support our meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods

For the purposes of this study, we defined the Mediterranean area as

the region incorporating countries around the Mediterranean Sea in

Europe, Asia and Africa. We thus collated epidemiologic data on HL from

Spain, France, Italy, Croatia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Albania, Greece,

Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria,

and Morocco (specifically the Maghreb region in Northwestern Africa).

We derived the most recent estimates on HL incidence and mortality from

the updated International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) online

database, GLOBOCAN 2012.[4]

Furthermore, more accurate

statistics from the latest volume of Cancer Incidence in five

continents (CI5, X version) were used to improve the quality of these

data.[5] Additional information was

obtained from various local cancer registry reports available.

Data regarding HL mortality and time trends for the specified

Mediterranean countries were derived from the World Health Organization

(WHO) mortality database online.[6]

Most of the

countries included in our analysis have previously published relevant

data on HL epidemiology, though the level of coverage, accuracy and

updating varies considerably both within and between countries. For

this reason, temporal trends for HL incidence, mortality and survival

are reported only for those countries in which the collection activity

of cancer registries covered a sufficiently wide period.

Hereafter, we refer to classical HL in this report.

Etiologic Epidemiology

Role

of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and other viruses.

Based on either epidemiological findings (e.g. bimodal age-incidence

curve, social-class risk factors, role of protected childhood

environment) or clinical features (e.g. fever, night sweat, weight

loss, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or IL-6 in serum) it has

long been hypothesized a viral etiology for HL.[7-8]

The ubiquitous B-lymphotropic oncogenic Herpesvirus, EBV, has been

proposed as the major candidate for a pathogenetic role due to at least

three pieces of evidence: the biological plausibility of EBV-mediated B

cell transformation, the presence of clonal EBV genomes within HL tumor

cells and three-fold elevated risk of HL in persons with a history of

infectious mononucleosis.[9-11]

Globally, EBV-positive HLs account for up to 40% of all HL cases, and

they have been shown to vary substantially by patient demographic and

tumors characteristics. The presence of EBV in HL is strongly

associated with specific epidemiological features including male

gender, Hispanic ethnicity, mixed cellularity subtype, children and

older adults, lower socio-economic status.

The rate of EBV-positive among HLs differs markedly worldwide

especially with respect to geography: in North America and Western

Europe, EBV was detected in 30 to 50% of HL patients, while in some

parts of Latin America, Africa and Asia the percentage is much higher,

reaching roughly 100% in children.[12]

For instance,

in Peru and Mexico incidence of EBV positivity among HLs ranged from 50

to 95%, in China was 65% and in Kenya reached 92%.[13-17]

Previous mentioned clinicopathological features of EBV-associated HLs

were also maintained across Mediterranean countries, where the

frequency of EBV-positivity was 90% in Greece, 61.5% in Turkey, 50% in

Egypt, 48% in Italy and 30% in Israel (even if Bedouin patients showed

a 66.7% rate of EBV infection).[18-20]

The scenario is quite different for EBV-negative cases, in which a

delayed exposure to common childhood virus other than EBV, such as

other Herpesviruses and Polyomaviruses, has been postulated having a

causative role in the development of HL. However, to date, no

consistent association between any virus and EBV-negative HLs has been

described.

Conditions characterized by immune dysregulation and an

immunodeficiency status may cause a predisposition to the development

of this malignancy. In addition, the main cause of immunodeficiency

relies on HIV infection in developed as well in developing countries.[21] As a result, the risk of developing

HL in HIV patients was estimated at 11-18-fold higher than in the

general population.[22]

Given the remarkable 2012 estimated number of people newly infected

with HIV of 32.000 and 29.000 in Western and Central Europe and Middle

East and Northern Africa respectively, such infectious disease is like

to continue to be responsible for a proportion of HL cases in this

area.[23]

Tubercolosis

and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Another interesting causative relationship is that existing between HL

and tuberculosis (TBC). Nevertheless, apart from some case reports, the

literature lacks epidemiologic studies aimed at investigating such

association.

Both diseases share a pathobiology closely related to the loss of

immune-surveillance of the host and, at the same time, side effects of

anti-lymphoma treatment include immunosuppression, a well-known

predisposing factor for TBC.

Consequently, the risk of TBC is generally higher in HL patients,

especially across endemic areas for TBC infection, such as the African

and the Asian continents. In such regions, TBC has been described to

precede but also to be concomitant or subsequent to HL.[24-26]

Additionally, in some cases, HL and TBC can show similarities in terms

of clinical presentation and course, laboratory tests and imaging

findings.[27]

Thus, the opportunity to distinguish between these two disorders

represents a diagnostic challenge in countries with high prevalence of

TBC.

Familial

aggregation and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Early reports from familial cases of HL provided initial evidence

towards a possible genetic predisposition as well as a role of shared

environmental risk factors in the pathogenesis of HL. Moreover, the

variability of HL incidence across different races, with rates higher

in Jews and lower in Asians, further support this thesis.

HL risk was found to be nearly 100-times higher in identical than in

fraternal twins[28]

and over time multiple case-control and cohort studies have reported a

threefold to ninefold higher risk of disease in first-degree relatives

of HL patients.[29-30] These

findings have been

recently confirmed by linkages of population-based cancer and family

record registries, in which considered large sample size and are less

vulnerable to biases with respect to previous studies. Among them, a

large study using data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database and the

Danish Cancer Registry, found a significantly increased risk of HL in

first-degree relatives of patients with HL in both populations, with

relative risks of 3.47 (95% CI, 1.77– 6.80) in Sweden and 2.55 (95% CI,

1.01– 6.45) in Denmark and a pooled estimate of 3.11 (95% CI,

1.82–5.29).[31]

The risk of familial HL presented a heterogeneity of effect since it

has been shown to vary by age, sex and degree of familial relationship.

The greatest risk was seen for siblings than for parents of HL

probands, for families of probands under 40 years (RR=4.25), for male

relatives of patients. In addition, an earlier onset for familial than

non-familial cases was found.[32]

Increasingly, recent genome-wide analyses of candidate susceptibility

genes identified various HLA class II polymorphisms (i.e. DRB5-0101

allele, DRB1*1501-DQA1*0102-DQB1*0602 haplotype and TAP 1 allele) as

well as polymorphisms of several cytokine genes (e.g. IL6, IL1R1, IL10,

IL4R) which have been linked to risk of HL.[33-36]

Furthermore, a genome-wide linkage screen performed in 44 high risk HL

families showed the strongest linkage finding on chromosome 4p near the

marker D4S394.[37]

In summary, these findings support a multifactorial disease model for

the pathogenesis of HL involving both genetic and environmental risk

factors.

Descriptive epidemiology

HL

incidence patterns and time trends.

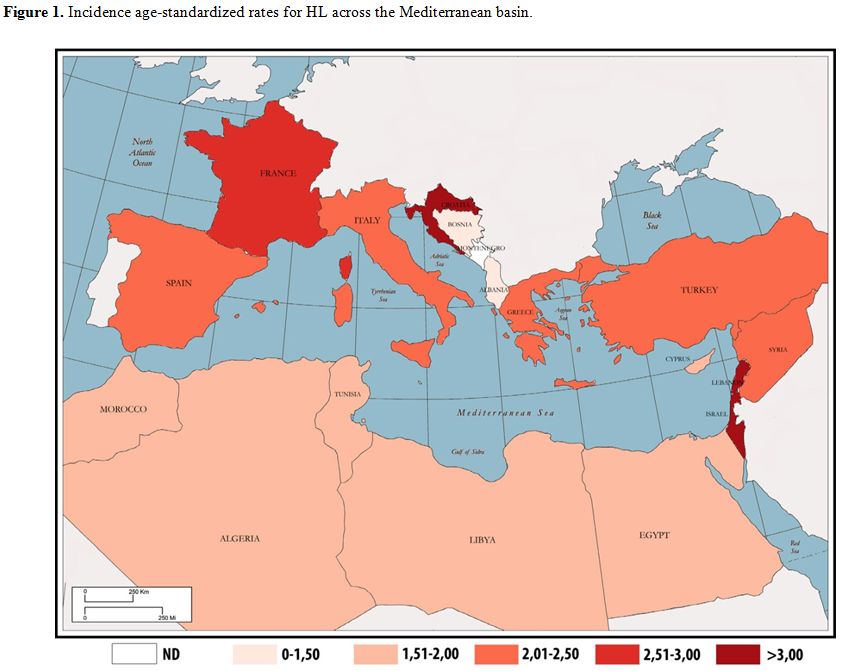

Based on its epidemiological features, including in Mediterranean

countries, HL incidence rates are higher in southern Europe, with the

exception of Israel and Lebanon. The highest incidence of HL was in

fact recorded in Israel in 2012 with an estimated incidence

age-standardized rate (ASR) of 3.71 per 100,000, followed by Lebanon

(ASR=3.67), Croatia (ASR=3.09), France (ASR=2.61) and Italy (ASR=2.39).

The lowest incidence was recorded in Albania with an ASR of 1.1 per

100,000. Other countries with a low HL incidence included Bosnia

Herzegovina (ASR=1.34), Egypt (ASR=1.51), Morocco (ASR=1.7) and Algeria

(ASR=1.83).[4] These data are

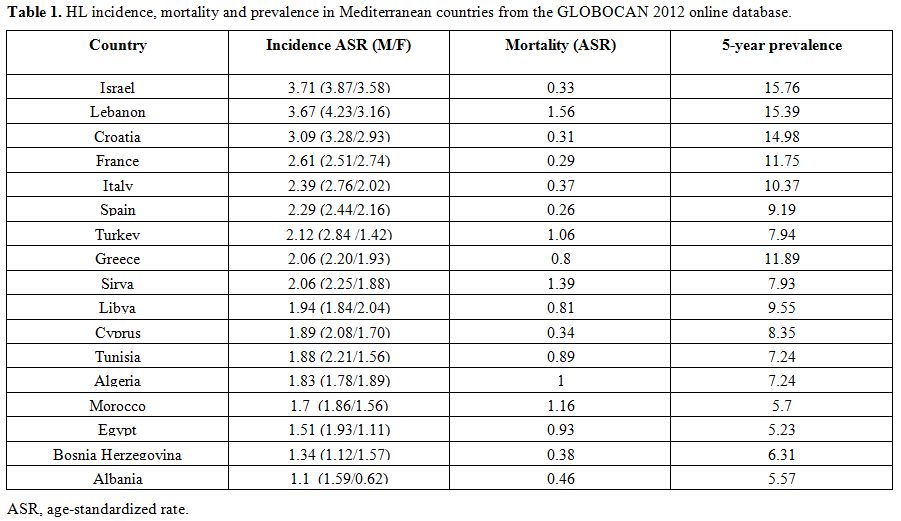

reported in more detail in Table

1.

| Figure 1. Incidence age-standardized rates for HL across the Mediterranean basin. |

| Table 1. HL incidence, mortality and prevalence in Mediterranean countries from the GLOBOCAN 2012 online database.Incidence age-standardized rates for HL across the Mediterranean basin. |

GLOBOCAN

2012 estimates of HL incidence were found to be globally in line with

the above population-based data, although some interesting differences

were observed. In this regard, we found consistent variation in the

recorded HL incidence rates between Globocan and published cancer

registries data in Israel, Cyprus, Croatia and also among Algerian men.

Of particular note, the most updated incidence data from the Israel

National Cancer Registry reported lower rates than GLOBOCAN 2012 i.e.

ASRs of 3.14 and 3.21 reported in Jewish men and women, respectively,

and an ASR of 2.62 reported for non-Jewish women differed from the

GLOBOCAN estimates; the only comparable rate was for non-Jewish men

(ASR=3.87).[38] Estimates and

population-based data

from the more developed Mediterranean countries on HL were comparable

to those of other industrialized regions worldwide, such as the United

States which reports an incidence of 2.8 per 100,000 men and women per

year.[2]

In Italy, the ASR for HL reported by Associazione Italiana Registro

Tumori (AIRTUM) was 3.4 per 100,000 in both sexes in 2008. More updated

data have revealed a slight geographic gradient in HL incidence across

the Italian peninsula from north to south but this was not a

statistically significant variation. The 2006-2009 European ASRs for HL

by sex and geographic area were as follows: north (4.1), center (3.8)

and south/islands (3.8) in men and north (3.3), center (3.5) and

south/islands (2.8) in women.[39]

About time trends,

the HL incidence rates remained relatively stable among industrialized

countries, comparable to the recorded rates in the United States which

changed minimally over time; a significant increase in HL rates has

only been seen only among blacks (APC=1.0) and Asians/Pacific Islanders

(APC=2.2) since 1992.[2] Recent

epidemiologic analysis

conducted in Spain has revealed no significant frequency variations in

HL incidence between 2000 and 2009.[40]

Some

exceptions have been found in other part of Europe however:

statistically significant 2.6% and 2.2% annual percentage increases in

the HL rates in Italy have been documented by the AIRTUM in men and

women, respectively, during the 1996-2010 period.[41]

About the incidence in other countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea

in recent years, a population-based study from the Israel Cancer

Registry reported a significant and persistent rise in the ASR in both

sexes between 1960 and 2005 in the Jewish population. Of particular

note, in Israeli-born young Jewish adults, the ASR rose from 2.27 per

100,000 during the 1960-1969 period to 3.61 during the years 1997-2005.[42] Thus far, no HL incidence trends

have been available for low-income countries in the Mediterranean basin.

Mortality

patterns and time trends.

Mortality rates due to HL vary markedly across the Mediterranean

region; the estimated 2012 mortality ASRs range from 0.26 per 100,000

in Israel to 1.56 per 100,000 in Lebanon. A correlation between

socio-economic status and death from HL has also emerged within this

region. High income countries such as Spain, France, Israel and Italy

showed mortality rates of 0.26, 0.29, 0.33, and 0.37 per 100,000,

respectively. On the other hand, higher mortality rates have been

recorded in Lebanon (ASR=1.56), Syria (ASR=1.39), Morocco (ASR=1.16)

and Turkey (ASR=1.06).[4] Data on

HL mortality in Mediterranean regions are summarized in more detail in Table 1.

Over the past 40 years, trends in mortality have progressively

decreased worldwide, though they have been variable across countries.

Since the late 1950s, mortality rates have steadily declined in

industrialized countries. ASRs have plummeted from 2.27 to 0.44 in men

and from 1.40 to 0.29 in women in Italy, from 1.47 to 0.37 in men and

from 0.88 to 0.24 in women in France and from 1.04 to 0.41 in men and

from 0.55 to 0.22 in women in Spain. In Italy, the same progressive

downward trend has also been reported by AIRTUM which has recorded a

drop in mortality rates for HL from 0.77 and 0.48 in 1992 to 0.40 and

0.27 in 2007 in men and women, respectively.[39]

In

contrast to the above data, no similar trends seem to have emerged from

low-income countries: the only available mortality time trends in this

regard are from Egypt and show no change over time.

Survival

patterns and time trends. Up to the 1960s, the 5-year

survival rate for HL was less than 10% worldwide.[43]

The outcome for patients diagnosed with HL has progressively improved

since then and the majority of cancer registries around the world

report current 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of up to 80% for

patients with advanced and more than 90% for limited stage disease.

Hence, HL may be currently considered to be one of the most curable

cancers worldwide.

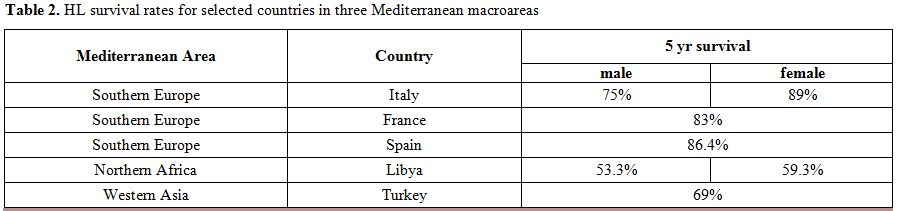

Overall, the highest survival rates for HL patients have been recorded

in western countries. In southern Europe the 5-year relative survival

(RS) rates are comparable to those of the United States and other

European countries. An international geographic comparison performed by

AIRTUM in 2011 has reported 5-RS rates for men of 82.3% in Italy, as

compared to 79.1% in the United States (SEER-17) and 82.5% in some

European countries (EUROCARE-4); among females, these rates were

slightly higher (85.1, 83.7% and 84%, respectively).[41]

In recent years, a Europe-wide study analyzing the survival of patients

with lymphoid neoplasms has indicated a 5-year RS of 84.5% for HL

patients diagnosed from 2000-2002. These rates were highest for

patients with LR (5-year RS, 93.1%) and lowest for LDC cases (5-year

RS, 54.4%). No statistically significant differences were found for CHL

between men and women (82.5% vs. 86%). That study also suggested that

previously noted differences in HL survival rates between regions have

tended to decrease, ranging from 81.4% in eastern Europe to 90.6% in

northern Europe.[44] Moreover, in

this study, the

outcome for patients with all lymphoid neoplasms, including HL, was

reported to decrease substantially with age, as has been well

documented for most types of cancer. Nevertheless, a large

population-based study from Sweden incorporating the results of

long-term follow-ups has recorded a significant 5-year and 10-year RS

improvement in all age categories, including the elderly but with the

exception of the very old (> 80 years).[45]

Furthermore, a relevant increase in survival for HL patients aged 45 to

59 years, and 60 years and older, was recently documented in a study

from the United States (increases in the 10-year RS by 24.8% and 23.3%

between 1980-84 and 2000-04, respectively).[46]

In contrast, the scenario is quite different in more economically

disadvantaged Mediterranean regions. For example, the Libyan Benghazi

Cancer Registry has reported a 5-year overall survival (OS) for HL

patients of only 53.3% in men and 59.3% in women during the period

2003-2005.[47] Turkey has reported

rates that halfway

between this and the outcomes in developed nations i.e. a 5-year RS of

69% for all ages and both sexes combined.[48]

A comparison of outcomes among three groupings of Mediterranean nations

is provided in Table 2.

| Table 2. HL survival rates for selected countries in three Mediterranean macroareas. |

Discussion

The epidemiology of HL has always been of interest to cancer

researchers because of its heterogeneous patterns of presentation, and

several etiopathogenetic theories have emerged over time. This complex

pattern was also found to be replicated among Mediterranean basin

populations, and several factors have been shown to exert their

influence on this phenomenon. Although data regarding HL incidence,

mortality, survival and time trends across this region are available

mainly for European countries and are sparse or absent for the majority

of other countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, we have highlighted

below several points of discussion for incidence time trends in less

developed nations.

First, it emerged from our current investigation that there is a

substantial variation in HL occurrence by geographic area: HL incidence

rates progressively decreased from industrialized European countries

such as France and Italy to less developed nations such as Albania and

Bosnia Herzegovina. This is clearly consistent with the earliest

findings of Correa and O'Connor, who first described the positive

correlation between degree of socio-economic development and risk of

HL.[49] There is a remarkable

differences in the

global occurrence of HL, with incidence rates higher in southern Europe

than in northern Africa and western Asia. That seem to be largely due

to a higher exposure in southern Europe to lifestyle and environmental

risk factors associated with economic transition (including smoking,

obesity, physical inactivity, and reproductive behaviors), as well as

availability of diagnostic practices and awareness of disease. In fact,

although little is currently known about HL pathogenesis, there is

accumulating evidence that the adoption of western world-associated

risk factors by low income countries, the so-called westernization, is

responsible for increasing the number of HL cases in such areas.[50]

A recent analysis performed by InterLymph has found that cigarette

smoking should be added to the few modifiable HL risk factors

identified to date, with a reported odds ratio (OR) of 1.10 in ever

smokers compared to never smokers. This increased risk was also

associated with MC (OR=1.60) and EBV-positive CHL (OR=1.80) among

current smokers.[51]

On the other hand, different genetic susceptibilities to HL between

different races may play an important role in explaining its variation

across countries. As already reported, Asians have a lower incidence of

HL than Caucasians and Blacks, which may indicate a genetic resistance

to this disease that is possibly related to HLA type.[52]

Nevertheless, in Israel, which belongs to western Asia, the HL rates

were found to be the highest of the Mediterranean region. In

particular, Israeli Jews had incidence rates of 4.17 and 5.57 in men

and women, respectively, aged between 15 and 34 years. These rates were

lower among Israeli non-Jews with ASRs of 3.02 in males and 1.57 in

females aged 15-34. These findings may suggest an influence of genetic

background on HL incidence, but environmental influence must also be

taken into account. In fact, Israeli Jews born in America and Europe

have shown the highest HL rates (4.16 and 6.51 in men and women,

respectively) at an equivalent age.[53]

Moreover, Au

et al. have previously corroborated the role of both genetic and

environmental factors in the occurrence of HL: Chinese immigrants in

British Columbia presented a significantly lower 25-year incidence for

HL compared to the rest of the population in this region (standardized

incidence ratio, SIR =0.34) but a still higher rate than would be

expected for the Hong Kong Chinese population (SIR=2.81).[54]

With regard to incidence trends, these have remained relatively stable

over time in western countries but have been increasing in regions

experiencing improved standards of living. This reported rise in HL

rates in less developed countries since the mid-1990s[55]

may be explained by westernization,[50]

the aging and growth of the population, or the adoption of behaviors

and lifestyles associated with economic development such as smoking,

less healthy diets and physical inactivity.

Over the coming decades, these factors will contribute to an increased

overall burden of cancer, especially in low income countries, where HL

is expected to rise among young adults by nearly 57% by 2035. Keeping

in mind all aspects of bias related to predictions, in the same year in

the East Mediterranean region, the estimated number of new HL cases

will rise from 8,374 to 13,110 per year.

Among European countries, the increase in incidence will be less with

the estimated number of new cases expected to rise from 20,410 to

21,076 annually in both sexes by 2035, with 76% (16,010) of these

patients aged below 65 years.

In southern Europe as well as in the United States, no consistent

patterns have been shown to date, with stable or slightly downward

trends recorded in men and less favorable rates in women, reflecting

the absence of any new identified causes of HL over the last few

decades.[56] The only exception to

this trend in

southern Europe has been in Italy, where a significant annual increase

in HL rates by 2.6% in men and 2.2% in women has been reported over the

period from 1996 to 2010. This increase seems not to have been due to

new risk factors in the Italian population, as evidenced by the

temporal stability of HL incidence seen in neighboring countries (i.e.

France and Spain).[57] A greater

attention to diagnostic procedures may in fact explain this trend.

The pronounced and isolated increase in the HL incidence in western

Asia among Israeli-born young Jewish adults from 1960 to 2005 is

currently a subject of investigation in which it has been hypothesized

that as yet identified factors are responsible. Regarding HL mortality,

as expected, we have found that countries with the lowest incidence

rates show the highest number of deaths from this cancer and vice

versa. The past few decades have been characterized by a significant

progress in the management of HL and the introduction of more effective

and less toxic front-line treatments within risk-adapted strategies

have made this a largely curable disease. In most western and northern

European countries, HL mortality has continued to steadily decline

since the late 1960s. However, in central and eastern European

countries this decrease has been relatively recent and in fact up to

the 1990s central and eastern countries were characterized by

unfavorable trends.[58]

Nevertheless, the clinical

outcomes for HL patients have been variable across the Mediterranean

basin. By comparing survival rates, we have found a particularly poor

prognosis for HL patients in northern Africa, where the rates for HL

are similar to those reported for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in more

developed countries (5-year RS=57%).

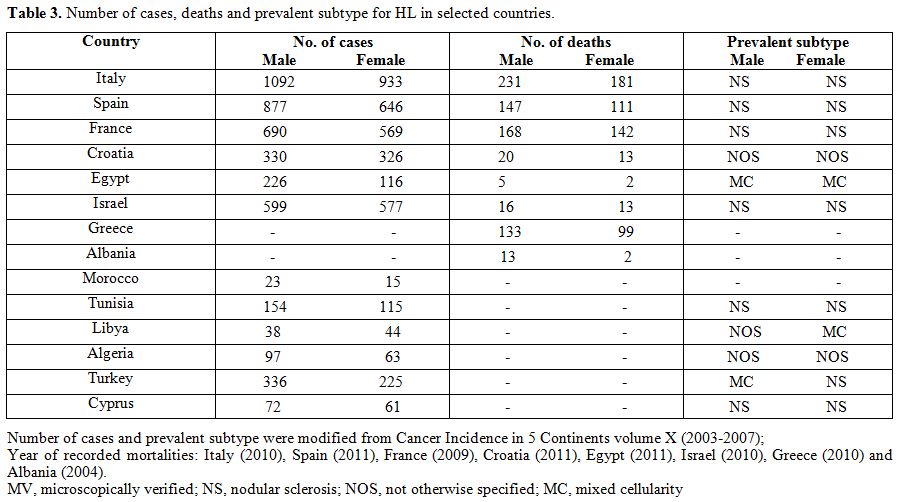

As reported by several authors, morphology strongly influences the

prognosis of HL patients. In particular MC, LD and not otherwise

specified (NOS) subtypes had significantly poorer outcome compared with

NS or NLPHL[59] At the same time,

HL subtype

distributions seem to vary across the Mediterranean basin. For example,

MC and NOS are more frequent in Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Turkey where

mortality rates are among the highest in this area (Table 3).

Unfortunately, no histological data are available from Lebanon, Syria

or Morocco, where the estimated HL mortality ASR peaks at 1.56, 1.39

and 1.16, respectively (Table

1).

However, differences in morphology explain only some of the geographic

variations observed in survival outcome. A study coordinated by Ben

Lakhal has suggested the presence of an intrinsically more aggressive

HL affecting less developed countries including Tunisia,[60]

but further evidence is needed to confirm this finding. More

importantly, a wide disparity in the availability of health resources

may better explain the difference in HL mortality recorded within the

Mediterranean basin.

| Table 3. Number of cases, deaths and prevalent subtype for HL in selected countries. |

Radiotherapy

represents an important resource for treating HL patients, particularly

for cases of limited stage disease, but its availability is still low

among Mediterranean low- and middle-income countries. In the Maghreb

area, only Egypt with 85% coverage and Morocco with 89% coverage can

provide an acceptable level of radiotherapy treatment. Libya has an

adequate number of machines but not all are utilized due to a lack of

cancer clinicians. In Albania, the issue is insufficient maintenance

support despite this country’s serious efforts to provide adequate

cancer care services to its citizens. The annual maintenance bill for

these machines of US$110,000 and requirement to replace one in three

machines at a cost of US$150,000 is beyond the budget of the Albanian

health system. In Syria the situation is not much better with only 2

radiotherapy centers operating at present serving 22.4 million people.[61]

In addition, the ever increasing costs of new and innovative therapies

may also contribute to the gap in survival outcomes that exist within

the Mediterranean region.

In conclusion, the provision of appropriate and accessible treatment

facilities along with an adequate number of clinical specialists in the

treatment of HL and other cancers represents a future challenge that

must be overcome to improve the outcomes of affected patients and treat

a largely curable type of cancer in disadvantaged regions.

References

[TOP]