Received: March 26, 2014

Accepted: June 10, 2014

Meditterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014049, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.049

This article is available on PDF format at:

Fina Vieira1, Mamadu Saliu Sanha1,2, Fabio Riccardi2,3 and Raffaella Colombatti2,4

1

Hospital Raoul Follereau, Bissau, Guinea Bissau.

2 Aid, Health and Development-Onlus.

3 Department of Biomedicine and Prevention,

University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

4 Clinic of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology,

Department

of Maternal and Child Health, Azienda Ospedaliera-University of Padova,

Padova, Italy.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Background:

Tuberculosis (TB) is widespread in Africa, but weak health systems in

developing countries, often display poor quality of care with delays in

case identification, irrational therapy and drug shortage, clinical

mismanagement, unnecessary expenditures for patients, reduced adherence

and increased mortality. Public-private partnership has demonstrated to

increase TB case detection, but less is known about its effects on

quality of care, mortality and costs for hospitalized TB patients.

Methods: Clinical outcomes and costs for TB patients at the TB National Reference Center of Bissau, in Guinea Bissau, West Africa, were determined during the first 5 months of the public-private management and compared to the ones of previous years when the hospitals was under direct Government’s management. Results: 215 (2009-2010) and 194 (2012-2013) patients were admitted, respectively. Improvement (p<0.05) was observed in mortality reduction (21% vs 6%), cause of death determination (50% vs 85%), treatment abandonment (15 vs 1). Direct costs for patients during TB diagnostic pathway and inpatient care were significantly reduced, 475 vs. 0 USD. Conclusions: Public-private partnerships displays significant short term benefits in National TB reference centers, even in post-conflict countries. Further studies could aid in determining the overall long term benefits of this type of cooperation, and the specific characteristic of TB and concomitant hematologic and infectious diseases in TB admitted patients. |

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) treatment has saved

more than 2 million people since 1995.[1]

Nevertheless, too many are not diagnosed, not treated or not properly

treated. Public-private partnership has increased Tuberculosis (TB)

case detection in different contexts.[2-3]

Weak health systems in developing countries, often display poor quality

of care, delays in case identification, irrational therapy and drug

shortage, unnecessary expenditures for patients and increased

mortality.[2,3] Despite a policy of

free drug

treatment, TB health services in many countries charge all income

groups, costs are high and adherence measures are inadequate.[4-5] Patients’ costs can be particularly

burdensome for TB affected households in Africa.[6]

Guinea-Bissau, in West Africa, has been experiencing annual military

coups since the 1999 civil war. The country's health indicators are

among the worst in Africa.[7]

Proportion of budget

spent on health is 2% of GDP, with total dependence on external

financial support to the budget of the Health Ministry. The payment of

salaries to health workers has often been subject to delay, and morale

is poor.[7]

TB incidence is 242/100.000.[1]

Case detection rate

for all forms of TB, at 48%, has been declining since it reached 81% in

1995, indicating a decline in programmatic performance.[1,7] The treatment success rate, for

smear-positive TB (60%) and other forms (about 55%) is low.[1]

The TB National Program operates through the National Reference Center

in Bissau, Hospital Raoul Follereau (HRF), Regional Hospitals in the

Regions and TB Health Centers throughout the country. According to the

National Guidelines, TB patients in poor clinical conditions or with

severe disease are admitted to the HRF, after referral from regional

hospitals or health centers.[8]

The National Reference Center for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, HRF,

is an 115 bed hospital which includes an in-patient service (three

words: men, women and children), an outpatient service, laboratory, two

X-Ray Units, a pharmacy, service area (kitchen, laundry, ironing) and

two cafeterias. Since October 1st

2012

the Health Ministry has entrusted the management of the HRF to the

International Organization, Aid, Health and Development (AHEAD). The

Government would give TB drugs received from international donors, pay

the staff salaries and provide electricity. AHEAD would supply a top-up

for the personnel and the diagnostic and treatment pathway for free to

inpatients (including exams, non-specific drugs, food). The public

hospital would be managed by the private sector, but within the

framework of the National TB Program. It was hoped that this

public-private partnership would improve the quality of diagnosis and

treatment of TB suspects, increase adherence while reducing mortality

and costs.

Materials and Methods

Methods

According to the National Guidelines,[8]

as part of

routine clinical diagnostic evaluation, patients who are admitted to

the HRF with a suspect of TB, received a three sample sputum analysis

and a thorax X-Ray. Ziehl-Neelsen’s sputum staining technique is used,

and patients are considered smear positive if acid fast bacilli are

shown on at least two samples. Sputum Culture and PCR are not available

in the country for the present being. Smear negative patients are

considered to have TB according to the physician’s evaluation of chest

X-Ray and clinical condition. Additional analyses (complete blood

count, biochemistry, urine and stool evaluation and culture) are

performed if necessary, based on physician’s judgment. TB is treated

according to the National Guidelines,[8]

with a four

drug regimen for two months (rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and

pyrazinamide) followed by two drugs for the following six months

(isoniazid and ethambutol); five drugs are used in case of relapsed TB

(streptomycin, rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide).

We evaluated all-cause mortality rates, adherence to the

hospitalization phase of TB treatment, diagnostic procedures and direct

costs for inpatients in the first 5 months of the public-private

management (October 1st

2012-February 28th

2013); furthermore, we compared them to the five months of the same

season in previous years (October 1st

2009-February 28th

2010), when complete data were available. Data on TB co-infections or

hematologic malignancies and severity score were seldom available and

not routinely utilized to grade and classify patients in both periods

and therefore could not be compared. No user fees were applied during

the public-private management while user fees were applied during

previous years under the Government direct management of the hospital

both during the diagnostic pathway and for admission. Patients’

clinical cards and hospital registries were used to cross-check

diagnosis, therapy and admission-discharge dates. Pearson's chi-square

test was used to compare variables within groups. p-values<0.05

were

considered statistically significant.

Materials and Methods

Results

The majority of patients came from Bissau (82% in 2009 and 71% in

2012); there was a slight increase in patients coming from outside the

capital in 2012 (29 % vs 18%).

No treatment abandonment was observed in the two periods, but 15 drop

outs were registered between January 2009 and May 2012 - when user fees

were applied - and only 1 between June 2012 and May 2013 - when

treatment was free.

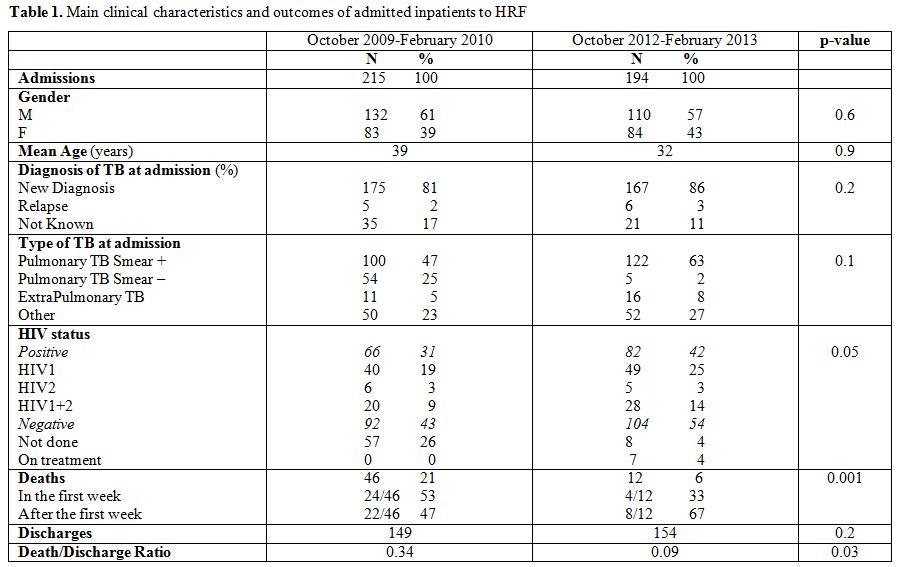

The clinical characteristics of admitted inpatients are detailed in Table 1.

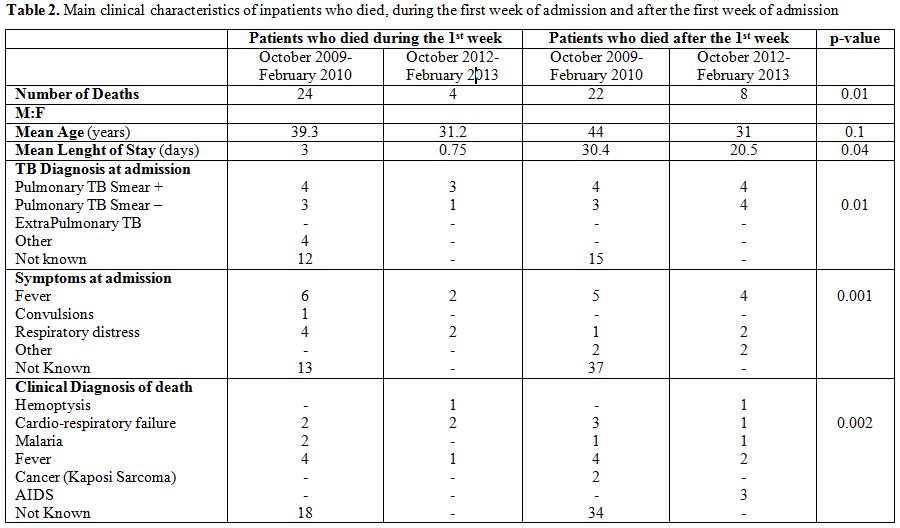

A significant reduction in mortality (21 vs 6%) was observed in October

2012-February 2013, both during the first week of admission and

afterwards (Table 1 and

Table 2).

Within the population of patients who died, the number of diagnostic

exams was significantly different, with improved quality of diagnostic

pathway in October 2012-February 2013 compared to October 2009-February

2010 (Figure 1 A-B).

This allowed a significant increase in the number of patients in which

the cause of death could be determined (Table 2).

| Table 1. Main clinical characteristics and outcomes of admitted inpatients to HRF. |

|

Table 2. Main clinical characteristics of inpatients who

died, during the first week of admission and after the first week of

admission. |

The

number and type of available drugs was also different in the two

periods with increased availability of i.v. antibiotics and

antimalarials in 2012-2013 compared to 2009-2010 (1.6 vs 0.2 per

patient).

Direct costs of TB diagnosis (XRays, BK analysis, Laboratory exams) in

October 2009-February 2010 were 31000 CFA per patient (65,11 USD) while

in October 2012-February 2013 they were zero. No direct cost for

hospitalization was required in October 2012-February 2013 while in

October 2009-February 2010 they were estimated in 195000 CFA per

patient (409,5 USD) (bed occupation, food, non specific drugs).

Discussion

Our experience suggests that a public-private partnership within the

framework of the National TB Program in a National Reference Center,

can be successfully implemented in a low resource and post-conflict

country. Even if a six months period is too short to evaluate long term

indicators, significant reductions in mortality and improvements in

diagnosis can already be observed in the short term.

In-hospital mortality for TB patients is multifactorial and remains

high in many countries.[9]

The significant reduction in mortality (21 vs 6%) observed in our

cohort was due to the reduction of mortality both during the first week

of admission and afterwards. Patients, usually admitted in severe

conditions, frequently have disseminated infections or comorbidities.

It is likely that patients have sought care earlier in the course of

the disease, knowing it was free of charge. Moreover, the increased

availability of diagnostic tools, iv antibiotics, antimalarials and

saline solutions might have had an impact in the possibility of

physicians to manage acutely ill patients and therefore contributed to

the mortality reduction both in the first week of admission and

afterwards.[10]

No treatment default was observed since the free hospitalization

regimen was implemented; meaning that lack of will to be cured is not

an issue. TB patients in Africa often default in the hospitalization

phase: hospitalization is problematic due to poor general conditions in

TB hospitals, costs incurred by patients during hospitalisation and

because patients need to earn living or take care of their families.[11]

Stock ruptures, shortage of reagents and drugs and low salaries produce

lack of motivation and poor morale impairing health personnel’s work

and dramatically reducing diagnostic and treatment performances in

Africa. The free care of severely ill TB patients, including drugs and

nutritional support, coupled with top-up for the personnel is likely to

have contributed to eliminate drop outs and reduce mortality after the

first week of admission.

Our short term analysis has several limits. First, we considered all

cause mortality and could not detail TB related mortality, mainly due

to the limited number of diagnostic exams performed in the first

period. It is likely that considering complete blood count and other

laboratory exams on a routine basis will allow a better definition of

other causes of mortality in TB inpatients such as acute anemia,

concomitant infections, hematologic malignancies, etc. Second, the

direct cost that were evaluated included the costs that are necessary

for TB diagnosis and inpatient care and not all the direct cost that

the patients experience, therefore they are probably underestimated and

overall direct costs are likely to be higher in both periods. Third, a

short term evaluation of public private partnership in only five months

does not allow detailing all the benefits and drawbacks of such a

collaboration. Nevertheless, post conflict and low resource countries

such as Guinea-Bissau that do not seem able to find rational and

appropriate ways to come out of isolation and to tackle health

challenges, desperately need positive experiences. We think it’s worth

reporting the improvement obtained in a short period of time of a

public-private international partnership in order to move forward and

enhance TB diagnosis, definition of co-morbidities, treatment and care

in the long term.

Conclusion

The main challenge in fighting the TB epidemics in Sub-Saharian Africa is to improve the sanitary system. Our experience demonstrates that international public-private partnerships in TB hospital settings can contribute, in the short term, to increase adherence to the hospitalization phase of intensive treatment, improve quality of diagnosis and care and reduce mortality through a free pathway of diagnosis and care.[12]

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank the Ministry of Health, the National

Program Against Tuberculosis, the staff of the Hospital Raoul Follereau

and all the patients and their families.

References

[TOP]