Received: May 20, 2014

Accepted: June 20, 2014

Meditterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014050, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2014.050

This article is available on PDF format at:

Antoine Thyss, Esma Saada, Lauris Gastaud, Frédéric Peyrade and Daniel Re

Haematology

Department; Centre Antoine-Lacassagne , 33 Avenue de Valombrose, 06189

Nice cedex 2, France.

|

This

is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract Hodgkin

Lymphoma HL can be cured in the large majority of younger patients, but

prognosis for older patients, especially those with advanced-stage

disease, has not improved substantially. The percentage of HL patients

aged over 60 ranges between 15% and 35%.A minority of them is enrolled

into clinical trials. HL in the elderly have some specificities: more

frequent male sex, B-symptoms, advanced stage, sub diaphragmatic

presentation, higher percentage of mixed cellularity, up to 50% of

advanced cases associated to EBV. Very old age (>70) and

comorbidities are factor of further worsening prognosis. Like in

younger patients, ABVD is the most used protocol, but treatment outcome

remains much inferior with more frequent, severe and sometimes specific

toxicities. Few prospective studies with specific protocols are

available. The main data have been published by the Italian Lymphoma

Group with the VEPEMB schedule and the German Hodgkin Study Group with

the PVAG regimen. Recently, the Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Study

Group published the SHIELD program associating a prospective phase 2

trial with VEPEMB and a prospective registration of others patients.

Patients over 60y with early-stage disease received three cycles plus

radiotherapy and had 81% of 3-year overall survival (OS).Those with

advanced-stage disease received six cycles, with 3-year OS of 66%.The

role of geriatric and comorbidity assessment in the treatment’s choice

for HL in the elderly is a major challenge. The combination of loss of

activities of daily living combined with the age stratification more or

less 70y has been shown as a simple and effective survival model. Hopes

come from promising new agents like brentuximab-vedotin (BV) a novel

antibody-drug conjugate. The use of TEP to adapt the combination of

chemotherapy and radiotherapy according to the metabolic response could

also be way for prospective studies.

|

Introduction

Both

the clinical management of older patients with cancer and the design of

research studies pertinent to this population remain major challenges.

This statement is particularly true for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL): in

younger patients, HL is cured in the vast majority, but results remain

disappointing for older patients, especially those with advanced-stage

disease.[1]

For the treatment of HL in elderly, there is a major contrast between

the relative disease frequency in older patients and the rarity of the

studies specially targeted at this population. HL in older patients is

not a very rare disease: in the epidemiological data from the US

government, the age adjusted incidence in 2006-2008 for HL ≥ 65

represents 17.7% of all HL.[2]

Population-based epidemiological studies typically show a bi-modal peak

of HL incidence:[1-11] the first

around 30-35 years old, the second beyond 55-60.[7]

The proportion of HL patients aged > 60 ranges in the different

reports between 15% and 35%;[6,9-12]

accordingly the 26.7% of biopsies of HL, collected between

2006-2011 in a database, grouping all pathologists of the department of

the Alpes-Maritimes in the south of France, and including also our

cancer centre, was from patients aged > 60

(unpublished data).

Several recent series have specified the relative incidence of HL in

the elderly and identified specific prognostic factors in this group of

patients;[1,3-7,10,11,13,14]

however, only a minority of them are enrolled in clinical trials.[10]

Specificity of HL in the Elderly

Age itself is one of the important prognostic factors in Hodgkin

Lymphoma (HL) and is included in the prognostic scoring system of some

of the main cooperative groups such as EORTC or Canadian-ECOG, as in

the international prognostic index for advanced HL[8]

but not for the German Hodgkin Study Group, GHSG. For example, age over

50 is an unfavourable prognosis factor for the EORTC group. Patients

over 60 are rarely eligible and/or included in the prospective trials

of these groups. Moreover, International Prognostic Index (IPS) is the

most used model for predicting prognosis in advanced-stage HL patients8

but it must be noted that no patient with an age > 65 was

enrolled

in the study. Patients aged > 60 years have a 5-year event-free

survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) rate of 30-40% and 40%-50%,

respectively.[12,15,16]

These figures are significantly inferior to those reported in the adult

patient.[3]

However, HL survival for all age groups increased in the last two

decades, even in the age subset over 60, where no major advances in

treatment efficacy were recorded, indicating an overall improvement in

patient care.[1,3]

Several reports stressed the difference in pathogenetic mechanisms,

tumour pathobiology, host-related factors, clinical presentation,

symptoms and prognosis for HL affecting the elderly as compared to the

adult.[4,5,13]

There are many

differences between the presentation of HL in the elderly in comparison

to that of the younger patients: (a) mixed cellularity is more frequent

ranging from 31% to 50%;[1,13] (b) 34% of cases and up to 50% of

advanced cases show the presence of EBER or LMP-1 proteins in

Reed-Sternberg cells[6] (these two

points are not independent); (c) B-symptoms and advanced

stage are much more common than in adults.[7]

Male sex and sub-diaphragmatic presentation are also more frequent in

patients over 50. Age over 70 is a factor of further worsening

prognosis,[1,9]

as is co-morbidity.[1]

The latter seems to play an essential role in predicting treatment

outcome: in a retrospective analysis, stage, B symptoms and presence of

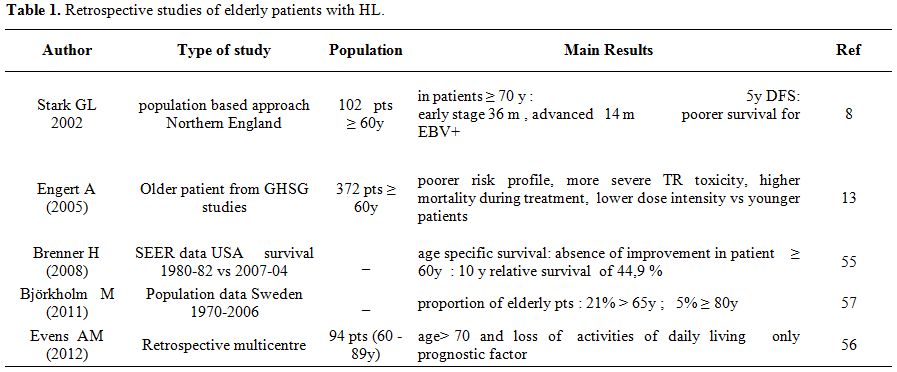

co-morbidity were independently associated with inferior survival.[12] Several recent retrospective

studies, mainly on population databases, have pointed out these

particularities (table 1).

| Table 1. Retrospective studies of elderly patients with HL. |

Management of HL in the Elderly

There is no true consensus for treatment of HL in the elderly. After

full staging, including PET–scan, geriatric assessment and evaluation

of co-morbidities, the principles of treatment can be resumed as

follows: for stages 1A and 2A, a short chemotherapy program

of

two cycles, possibly prolonged to four courses in case of poor risk

features, followed by involved fields (IF) radiotherapy. For advanced

stage, it is often claimed that a prolonged use of ABVD (i.e. 6 cycles)

could be also given to patients in good general status, but elderly

patients are often incapable to tolerate the regimen of six cycles of

ABVD, particularly because of the lung toxicity induced by bleomycin.

There is no consensual approach for frail patients. The number of

chemotherapy cycles might be reduced depending on the result of interim

PET-scans, even if data for this approach in this elderly population

are lacking.

The ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine)

has been considered the standard front-line treatment for HL patients[17]

and remains a gold standard, especially for limited-stage HL.

Obviously, treatment outcomes with ABVD in elderly patients remain

inferior to those obtained in younger patients.[18]

Moreover, toxicities are more frequent and severe in older patients,

and treatment dose intensity is often reduced because of toxicity

and/or co-morbidity and some specific toxicities are observed, as lung

toxicity of bleomycin reported as high as 46% in some series.[18,19]

A frequent approach in geriatric oncology or haematology to reduce

toxicity of chemotherapy is the development of specific protocols that

reduce dose intensity and/or omit or replace some drugs with

age-associated toxicity. This approach often permits a better tolerance

but is systematically associated with a reduction of response and

survival, as compared to younger adult patients. For example, the role

of relative dose intensity (RDI) has been questioned by the German

Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) in the elderly HL patient: a significantly

lower RDI was observed in older HL patients[2]

and patients with a RDI < 65% had poorer outcomes than patients

receiving higher chemotherapy doses.[9]

Taken together these data stress the concept that in elderly patients,

non-HL events affect survival in a more significant way compared to

younger patients.

In the late 1990s, the GHSG carried out a prospectively randomized

study to compare the baseline BEACOPP regimen against COPP-ABVD, their

standard regimen at the time.[20]

Between February

1993 and 1998, 75 patients aged 66 – 75 years with newly diagnosed HL

in advanced stages were recruited into the HD9 trial as a separate

stratum (HD9 elderly). Patients were assigned to eight alternating

cycles of COPP and ABVD or eight cycles of BEACOPP in baseline doses.

Radiotherapy was given to initially bulky or residual disease. In

total, 68 of 75 registered patients were met assessment criteria: 26

with COPP-ABVD and 42 with BEACOPP baseline. There were no significant

differences in terms of complete remission (76%), overall survival

(50%), and freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) (46%) at 5 years. Two

patients (8%) treated with COPP-ABVD and nine patients (21%) treated

with BEACOPP died of acute toxicity. They concluded that both regimens

gave limited results in elderly patients, and that baseline BAECOPP was

too toxic. The use of the escalated BEACOPP, the standard regimen of

the GHSG for advanced stage HL in younger patients, is excluded for

patients over 60 years because of excessive toxicity.[21]

Prospective HL Studies Specifically Designed for Older Patients

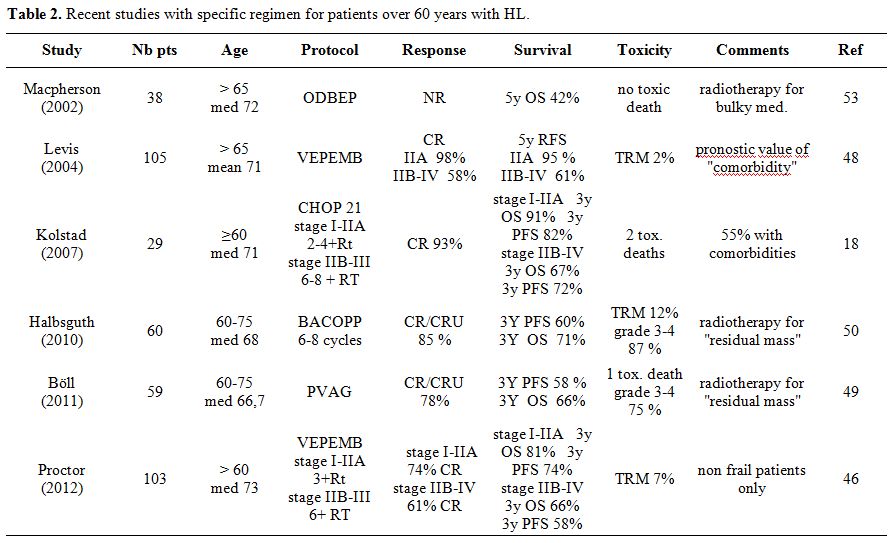

Very few prospective HL studies designed specifically for older patients are available. All studies published since 2000 are listed in Table 2. Some non-ABVD chemotherapy regimens containing different alkylating agents have been published and are also listed in Table 2.

| Table 2. Recent studies with specific regimen for patients over 60 years with HL. |

Macpherson

et al. have proposed in 2002 a new protocol called ODBEP (vincristine,

doxorubicin, bleomycin, etoposide and prednisone).[22]

They compared 38 patients aged over 65, treated with this regimen, with

an historical control group of 17 patients treated with

MOPP/ABV-variant, a standard regimen in the 1980s. With a median

survival of 43 and 39 months, and five-year overall survival (OS) of

42% and 32%, respectively, there was no statistically significant

difference between the two treatments; however, ODBEP appeared to be

less toxic.

The Italian Lymphoma Group Results published the results with the

VEPEMB schedule (vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, prednisolone,

procarbazine, etoposide, mitoxantrone and bleomycin).[12]

This study included 105 evaluable patients over 65 (mean 71 years,

range 66–83), with 48 (46%) stages I-IIA, and 57 (54%) stages IIB-IV.

Co-morbidity defined only as “the presence of a concomitant disease,

requiring specific treatment” was observed in 39 patients (37%). The CR

rate was 76%, respectively 98% for stage IIA and 58% for stage IIB-IV,

and the five-year RFS rate of patients entering CR was 82%,

(respectively 95% and 66%). In multivariate analysis, stage, systemic

symptoms, and co-morbidity had independent value in affecting OS, DSS,

and FFS. Surprisingly, despite the use of bleomycin, no pulmonary

toxicity is mentioned, raising the question of this systematic

evaluation.

The same regimen has been used by the Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma

study group (SNLG) in the SHIELD program[23]

for 175 patients, associating a prospective phase 2 trial of VEPEMB

with 105 patients with a prospective registration study of patients not

treated as part of the VEPEMB study. This trial included patients too

frail to receive standard therapies and patients managed with curative

intent using alternative treatment regimens, including 35 patients

treated with ABVD. This somewhat complicated program was designed to

recruit all patients representative of the target population in

participating centers. Initial evaluation of the patients involved a

formalized assessment of co-morbidity using a modified ACE-27

co-morbidity scale. Patients designated as “non-frail,” were eligible

for the phase 2 VEPEMB protocol. Those designated as “frail” were

eligible for entry into the registration arm of the study and were

treated at their physician’s discretion. Of 103 VEPEMB patients over 60

(median age 73), 31 had early-stage disease (stage 1A/2A) and received

VEPEMB three times, along with radiotherapy. The median follow-up was

36 months. Complete remission (CR) rate (intention-to-treat) was 74%,

and three-year overall survival (OS) and progression free survival

(PFS) were 81% and 74%, respectively. A total of 72 patients had

advanced-stage disease (stage 1B/2B/3 or 4) and received VEPEMB six

times. CR rate was 61% with three-year OS and PFS of 66% and 58%,

respectively. Overall TRM was 7%.

Another new regimen has been developed by the GHSG in the same period

in early unfavorable and advanced stages, the PVAG regimen (prednisone,

vinblastine, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine).[24]

In a

phase 2 study, 59 patients with HL aged 60 to 75 (median, 68 years) and

with “normal organ function” and good general condition (WHO-Index ≤ 2)

received 6 to 8 cycles of PVAG and additional radiotherapy if they were

not in complete remission (CR) after chemotherapy. CR/CR uncertain was

obtained in 46 patients (78%). The three-year estimated for OS and PFS

were 58% (95% CI, 43%-71%) and 66% (95% CI, 50%-78%), respectively. WHO

grade 3/4 toxicities were documented in 43 patients (73%), with one

treatment-related death. These results are very close to those of their

previous BACOPP regimen for survival, with less toxicity.

A study of Kolstad et al.[25]

reported for the first

time the results of the CHOP-21 regimen, largely used in non-Hodgkin’s

lymphoma. In this single institution’s study with 29 patients aged 60

to 91, 11 stage-I/II patients received 2-4 cycle followed by

radiotherapy and 18 stage-IIB/IV patients received 6-8 cycles, without

radiotherapy for 13/18. Two treatment-related deaths occurred, but the

complete response rate of CHOP ± radiotherapy was 93% and OS and PFS at

three years were 79% and 76%, respectively. Unfortunately, these

impressive results of CHOP-21 in elderly HL as not been confirmed by

other groups.

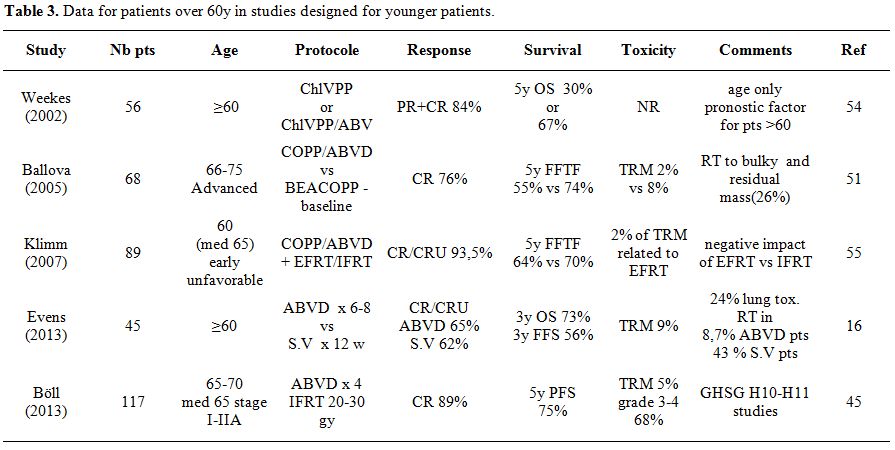

Studies Designed for Younger Patients but Including Patients over 60 Years

Other studies designed for younger patients have included patients aged over 60. They are listed in Table 3.

| Table 3. Data for patients over 60y in studies designed for younger patients. |

In

2002, the Nebraska Study Group in a retrospective comparison of ChlVPP

vs. hybrid ChlVPP/ABV in 56 patients over 60 years, showed a major

survival difference with a five-year OS of 30% vs. 67% respectively and

conclude that adriamycin should be considered as a major component of

the chemotherapy regimen in these patients.[15]

None of the usual clinical features were significant predictors of OS

in patients above 60.

In the multicenter HD8 study of the German Hodgkin’s Study Group, 1064

patients with early-stage unfavorable HL were randomized to

receive 4 cycles of chemotherapy (2 COPP alternated with 2 ABVD),

followed by either radiotherapy (RT) of 30 Gy extended field (EF) + 10

Gy to bulky disease or 30 Gy involved field (IF) + 10 Gy to bulky

disease. Of these, 89 patients (8.4%) were ≥60 years. Acute toxicity

from RT was more pronounced in elderly patients receiving EF-RT

compared with IF-RT. Freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) 64% vs. 87%,

and OS 70% vs. 94% after 5 years was lower in elderly patients compared

with younger patients. Elderly patients had poorer outcomes when

treated with EF-RT compared with IF-RT in terms of FFTF (58% versus

70%; P = 0.034) and OS (59% versus 81%; P = 0.008). The main conclusion

was that EF-RT after chemotherapy has a negative impact on elderly

patients with early-stage unfavorable HL and should be avoided.[26]

The German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) has tested the BACOPP regimen

that consists of bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine,

procarbazine, and prednisone.[27]

Compared with the

BEACOPP baseline, a regiment largely studied by this group, etoposide

was omitted, and the anthracycline dose was increased as they

considered that anthracyclines might be one of the most relevant

components of chemotherapy for HL in older patients. Sixty five

patients with early unfavorable or advanced stage HL, aged between 60

and 75 years, were enrolled in this phase 2 trial. Treatment consisted

of 6 to eight cycles of BACOPP. Residual tumor masses were irradiated.

Of 60 eligible patients 51 (85%) achieved CR/CRu. With a median

observation time of 33 months, 18 patients died (30%), including 7

treatment-associated deaths. Grade 3/4 toxicities occurred in 52 (87%)

of patients. The PFS and OS rates for all patients at 3 years were 60%

(95% CI: 46%-73%), and 71% (95% CI: 59%-83%) respectively. Thus, they

considered this BACOPP regimen as active but compromised by a high

toxicity in older HL patients.

The U.S. intergroup trial E2496 comparing ABVD vs. Stanford V

(S.V) regimen has included 45 patients ≥ 60 years treated

with

ABVD (23 cases) or S.V (22 cases).[18]

Adjunctive

radiotherapy was delivered in 8.7% of ABVD patients and 43% S.V

patients with different criteria between these two groups. In these

patients, 5-year EFS and of 48% and 58%, respectively, were much

inferior to those obtained in younger patients (74% and 90%,

respectively). Moreover, in this trial, Bleomycin lung toxicity was

24%, mainly observed with ABVD (91%), and the death rate due to

Bleomycin toxicity was 18%. The overall treatment¬-related mortality

was 9% for older patients compared to 0.3% for patients aged <60

years. Overall, the death incidence without progression at two and five

years were respectively 13% and 22% for elderly patients, and

2%

and 9% for younger patients (p<.0001). These results stressed

that

both ABVD and S.V regimens are toxic and difficult to use for patients

aged above 60 and indicated the necessity of a precise evaluation and

selection of patients before the choice of treatment.

Böll et al.[2] reported in 2013,

for the GHSG, 117

cases of patients aged from 60 to 75 years (median 65) in a

cohort of 1299 patients, included in the HD10 and HD11

trials,

and treated with 4 x ABVD for limited HL (stage I or II). Despite the

selection of a favourable subgroup, the dose intensity delivered was

reduced and only 59% of the patients achieved a relative dose intensity

>80% compared with 85% for younger patients. In 14%, major

protocol

violations occurred, mainly because of excessive toxicity. Toxicities

of WHO grade 3 or 4 occurred in 68%, with 5 % of treatment related

mortality. The author conclude: “in patients ≥ 60 years with HL, four

cycles of ABVD are associated with substantial dose reduction,

treatment delay, toxicity and treatment-related mortality."

The escalated BEACOPP, which is the standard protocol for

advanced-stage HL for the GHSG and is much more toxic that ABVD, could

not be proposed in patients aged over 60y: in their HD9 study

the

treatment related mortality (TRM) rate was high (14.3%) in patients

over 60 years and neutropenic infections were the main cause

of

TRM.[21]

Role of Geriatric and Comorbidity Assessment in the Treatment Choice for HL in the Elderly

While definitions of the elderly patient remain vague, one can describe

the ageing process as a gradual loss of adaptation to stress due to a

diminution of the functional reserves of different organs. The process

is variable from one individual to another and thus, the mean life

expectancy of a 70 year-old patient varies from 6.7 to 18 years, and

that of an 80-year old patient from 3.3 to 10.8 years. In addition to

chronic pathologies (co-morbidities), geriatric syndromes (dementia,

incontinence, under-nutrition, etc.) further complicate medical

management. Clinical studies regularly exclude patients who are very

old, frail or suffering from co-morbidities, which makes the results

difficult to apply to these patients.

The clinician thus confronted a dual dilemma: should he treat with a

proven but unpredictable risk of hyper toxicity, or undertreat a

potentially curable patient and waste an opportunity. A recent review

points out this dilemma in hematologic malignancies[28]

but data are very scarce for HL. A range of techniques have been

advanced for assessing geriatric patients with a view to singling out

those capable of receiving a potentially toxic dose of chemotherapy.

The first step is to identify those most likely to benefit from

comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). This method involves

evaluating comorbidities, physical and psychic autonomy, nutritional

and cognitive status, level of depression, mobility and balance.

Unfortunately, the process is long, costly, complex and difficult to

use in clinical units in the absence of a dedicated geriatrician.

Other, simpler methods have been suggested but remain open to criticism

and with contradictory results.

Recently, Soubeyran et al. reported interesting results of the Oncodage

study in 1688 patients with solid tumors. They validated the G8 score,

a relatively simple instrument to detect patients presenting at least

one abnormal geriatric test among the following: Activity of Daily

Living (ADL), Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL), MMS,

Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS-15questions), Mini Nutritional

Assessment (MNA), Timed Get up and Go, and evaluation of

co-morbidities.[29] Although

constructed from

patients with solid tumors, the G8 test appears to be useable in

malignant hematology. In non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the GELA group

reported a prospective series of 150 DLBCL patients over 80 years

treated with low doses of CHOP and full dose of rituximab. A good PS

non-bulky disease (<10 cm), albumin >35 g/l, extra-nodal

sites

<2, and high ADL level were associated with improved overall

survival (OS) but in multivariate analysis, only albumin levels

superior to 35g/l were associated with longer OS.[30]

In HL the only prospective study including a co-morbidity assessment in

a patient over 60 years seems to be the SHIELD study, previously

described:[23] this study seems to

be more applicable

to everyday life, and serves more as a reflection than a tool for the

choice of treatment for an individual patient. In their retrospective

study, Evens et al. showed that the combination of loss of activities

of daily living and the age stratification of about 70 years gives a

simple survival model in elderly HL.[1]

Several series have shown that the presence of co-morbidities is

independently prognostic.[12,31,32]

Further trials should be designed to permit some flexibility to modify

or adapt the drug dosing or the regimen, on the basis of firm objective

criteria to avoid prohibitive toxicities. These trials may be able to

optimize the duration of treatment to the response according to PET

response (cfr. infra).

New Drugs

Brentuximab

Vedotin

(BV) is a promising novel antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD30 linked

to a potent synthetic antitubulin chemotherapeutic agent, monomethyl

auristatin E (MME). BV acts as a cell cycle-specific agent, like Vinca

alkaloid drugs, and induces G2/M-phase growth arrest.[33]

A multicenter phase II trial of BV in HL patients, recurring after

ASCT, demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 75% and a complete

response (CR) rate of 34% with a median duration of 20.5 months.[34]

The most common treatment-related adverse event was peripheral sensory

neuropathy, recorded in 42% of patients, but with complete resolution

after discontinuation of treatment in 50% of patients. A very similar

incidence of grade 2 or 3 peripheral polyneuropathy (52%) and symptom

resolution (54%) was reported by Gopal et al. in a small series (N=25)

of patients treated with BV for recurring HL after allogeneic bone

marrow transplantation.[35] A

higher rate of peripheral neuropathy was observed with weekly BV

treatment versus treatment delivered every 3 weeks.[36,37]

No association of more frequent or severe neuropathy with old age was

reported in any study, while a pre-existing neuropathy was found in

more than half of cases of neurotoxicity. The second most frequent

toxicity of grade 3 or more was haematological: anaemia (6-20%)

neutropenia (20% in both series), and thrombocytopenia (8%). A higher

rate of peripheral neuropathy was observed with weekly BV treatment

versus treatment delivered every 3 weeks.[36,37]

Bendamustine

hydrochloride

(Be) combines the antimetabolite activity of the purine-analogue

structure with the alkylating property of the nitrogen mustard group.

It is not a “new” drug, but its use in HL is recent. Because of its

distinctive activity profile, Be may show limited cross resistance with

agents usually employed for upfront and salvage treatments, and,

therefore, it has been proposed for the treatment of

relapsing/resistant HL. In two small phase II studies, enrolling nearly

70 patients aged 20-75, previously treated with 3-8 lines of

chemotherapy (including autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant),

the ORR and CR rate, after a mean of 3.8 cycles of Bendamustine,

administered intravenously at the dose of 120 mg/m2 on day 1 and 2

every 28 days, were, respectively, 50-53% and 29-33%. The mean duration

of response was 5 and 5.7 months.[38,39]

Corazzelli

et al., in a third phase II study reported similar results with 6-8

courses of Be at 70-120mg/m² in 41 relapsed or refractory HL patients

after 1-8 lines of chemotherapy, aged 18-85 years. The ORR and CR rate

were 58% and 31%, respectively.[40]

Despite being relatively short PFS, these rates of response in such

heavily pre-treated patients are encouraging.

The feasibility of Be treatment in patients aged 70 or more has been

explored more frequently in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). In a

large retrospective study of 465 CLL patients treated with Bendamustine

alone or in combination with rituximab, 91 were older than 70.[41] The most frequently administered

dose and schedule was 76-98 mg/m2,

twice per cycle every 21 days. Nearly 40% of patients experienced no

cycle delay, grade 3-4 blood/bone marrow AE occurred in 18.8% and

25.3%, respectively. In a multicenter phase II clinical trial from the

German CLL Study Group, among 117 previously untreated CLL patients

aged 34-78 years, 25.6% were aged > 70.[42]

Be schedule was 90 mg/m2

on days 1 and 2, every 28 days, associated to Rituximab. Grade 3 or 4

adverse events for neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anaemia were

documented in 19.7%, 22.2%, and 19.7% of patients, respectively.

However, in both reports, the myelosuppression, due to bone marrow

invasion by disease in all patients, and the association with Rituximab

could have negatively affected the haematological toxicity. Finally, in

a phase II trial in a small cohort of 20 elderly and frail patients

affected by Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), with a mean age of

72 (51-86), Be was administered at a dose of 90 mg/m2

on days 1 and 2 in association with Rituximab on day 0, every 28 days.[43]

The relative dose intensity (RDI) was 100%. Granulocyte colony

stimulating factor (GCS-F) was administered in only two patients and

only three grade 3 WHO (1 leukopenia and 2 anaemia) and one grade 4

(thrombocytopenia) toxicities occurred.

Taken together, all these data makes Be an interesting candidate for

use in combination for treatment of HL in elderly.

Other New Agents

Some other drugs are currently being studied and could potentially be used in the treatment of HL in the elderly because of a reduce toxicity compared to the usual chemotherapy regimen. Some epigenetic agents as HDACS inhibitors have shown encouraging results: for example, panobinostat, in a phase 2 trial, showed an ORR of 27%.[44] Lenalidomide an immune-modulatory agent with anti-angiogenic properties demonstrated a modest single agent activity, but may also be used in combination.[44,45]

Proposal for New Approaches

As the “gold standard” for younger patient, represented by ABVD, is more toxic and difficult to use with sufficient dose-intensity and efficacy in the elderly, there is room for new approaches in the treatment of HL in the elderly.

Treatment Adapted to the Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Response.

The early complete metabolic response, evaluated by PET after two

cycles of ABVD, has been demonstrated to be the most important

prognostic factor in 260 patients with advanced stage HL.[46]

Many protocols are testing the possibility of shortening chemotherapy

and/or omitting radiotherapy in adult patients, especially when in

early favourable stage. In the elderly, this criterion could be used to

propose chemotherapy of shorter duration, to avoid unnecessary

toxicities. This strategy seems to be particularly attractive in the

limited stages (I or II) in which radiotherapy can be use thereafter

without excessive toxicity, even in the population of older patients.

The major limitation of this strategy is that most elderly patients

with HL have advanced stage,[7] reducing the indications of

radiotherapy.

Combination

of BV with other chemotherapy compounds.

As BV is the only truly new drug with a major activity in HL without

unexpected toxicities in the elderly, its use in a first line

combination should be tested on elderly HL patients. Several reasons

could account for the synergistic activity of BV with other

antineoplastic drugs. First, differences between the cell types

targeted by each class of compounds may account for improved activity.

BV action is targeted against cells expressing CD30. CD 30 is found in

Hodgkin’s and Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells, which typically comprise only

0.1–1% of the total cell population within HL lesions.[47]

Chemotherapeutic agents, in addition to tumour cells, also target

proliferating stromal cell infiltrates, which constitute the majority

of the cell populations within HL lesions. By contrast, the cytotoxic

effect of free MMAE diffused from CD30+ malignant cells on bystander

cells may in part account for the significant antitumor activity of BV.[48]

Secondly, differences in the mechanism of action between MME-based ADC

and chemotherapeutic compounds may help to explain the increase in

efficacy.

Frontline treatment of advanced-stage HL, with BV at the dose of 1.2

mg/Kg in association with ABVD (Doxorubicin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine)

or AVD, proved very active in a phase I multicentre trial,

achieving respectively 95 and 96% of CR.[49]

The most

frequently reported (WHO grade ≥3) adverse effects were neutropenia and

peripheral sensory neuropathy present in 44% of the ABVD cohort, with 2

toxic deaths.[49] These results

with BV plus AVD are

promising, but it is possible that this combination will remain too

toxic for elderly patients.

Be seems to be a good candidate for such a combination as it have a

non-cross-resistant mechanism of action compared to BV combining the

antimetabolite activity of the purine-analogue structure with the

alkylating property of the nitrogen mustard group. In addition to

primary effects on tumour cells, Be has shown a peculiar activity in HL

by depleting the neoplastic microenvironment of tumour-supporting T-

and B-lymphocytes.[50,51] This

drug is already widely

used in patients over 70 with CL or low grade lymphoma, and toxicity is

easily manageable without dose reduction in case of renal

insufficiency.[52]

Conclusions

Existing data does not define an optimal first line treatment for

elderly HL patients. A comparison of existing trials is almost

impossible because of the small number of patients included in the few

published trials, lack of patient stratification (based on

co-morbidities or age cohorts, for example), heterogeneous

documentation of side effects such as lung toxicity, and varying

endpoints chosen to assess efficacy of treatment protocols.

Patient selection will be crucial for an effective treatment strategy

that could be modified based on interim PET imaging. In the absence of

clinical data, it is necessary to individualize treatment decisions

based on pre-treatment assessment scales and PET imaging. Based on our

clinical experience, it is of utmost importance to monitor patients

closely while on treatment in order to detect and control severe

treatment related complications.

Acknowledgments

Sandrine Pacquelet-Cheli provided editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. Katelyn Gordon and Anastasia Glazunova provided assistance for the revision of the manuscript.

References

[TOP]