Diagnosis and Subclassification of Acute Lymphoblastic

Leukemia

Sabina Chiaretti1,

Gina Zini2 and Renato Bassan3

1 Division

of Hematology, Department of Cellular Biotechnologies and Hematology,

“Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy

2 Hematology, Catholic University Sacred Heart

Policlinico Gemelli, Rome, Italy

3 Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit,

Ospedale dell’Angelo e SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Mestre-Venezia, Italy

Corresponding author: Sabina Chiaretti, Division of

Hematology, Department of Cellular Biotechnologies and

Hematology,“Sapienza” University of Rome, Via Benevento 6, 00161, Rome,

Italy. E-mail:

chiaretti@bce.uniroma1.it

Published: October 24, 2014

Received: September 18, 2014

Accepted: October 20, 2014

Meditter J Hematol Infect Dis 2014, 6(1): e2014073, DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2014.073

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is

a disseminated malignancy of B- or T-lymphoblasts which imposes a rapid

and accurate diagnostic process to support an optimal risk-oriented

therapy and thus increase the curability rate. The need for a precise

diagnostic algorithm is underlined by the awareness that both ALL

therapy and related success rates may vary greatly between ALL subsets,

from standard chemotherapy in patients with standard-risk ALL, to

allotransplantation (SCT) and targeted therapy in high-risk patients

and cases expressing suitable biological targets, respectively. This

review summarizes how best to identify ALL and the most relevant ALL

subsets. |

Introduction

Current standards for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) diagnosis

integrate the study of cell morphology, immunophenotype and

genetics/cytogenetics as detailed in the 2008 WHO classification of

lymphoid neoplasms.[1] The classification originally suggested by the FAB group is no longer followed.[2,3]

The FAB classification was clinically useful since it permitted

recognition of probable Burkitt lymphoma in leukemic phase, but it has

now been replaced by the WHO classification. Lymphoid neoplasms are

assigned, in the most recent WHO classification, to two principal

categories: neoplasms derived from B- and T-lineage lymphoid precursors

and those derived from mature B, T or NK cells. ALL belongs to the

first of these major groups, designated B- or T-lymphoblastic

leukemia/lymphoma[4] and including three principal

categories: B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma not otherwise specified,

B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with recurrent cytogenetic

alterations and T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. The designation of

leukemia/lymphoma reflects the principle that these neoplasms should be

classified on the basis of their biological and molecular

characteristics, regardless of the sites of involvement. The leukemic

variant shows diffuse involvement of the peripheral blood and the bone

marrow, while lymphoma is confined to nodal or extranodal sites, with

no or minimal involvement of the bone marrow. In the leukemic form, by

definition, the bone marrow must contain at least 20% blast cells. A

purely leukemic presentation is most typical of B-lineage ALL (85%),

while cases of T-lineage disease often present with an associated

lymphomatous mass in the mediastinum or other sites.

Diagnostic Morphology and Cytochemistry

A morphological bone marrow assessment represents the first step in

the diagnostic pathway, for the primary diagnosis of ALL and for the

differentiation from acute myeloid leukemia (AML),[5] since ALL, by definition, always presents with bone marrow involvement. Table 1[6]

shows the morphological criteria that are useful for distinguishing

between myeloblasts and lymphoblasts, however remembering the limits of

morphology in ALL, for which flow cytometry analysis represents the

diagnostic gold standard for both the identification of cell lineage

and the definition of subset. The morphology of leukemic cells in the

peripheral blood can be significantly different from that of the bone

marrow, which is always indispensable.

|

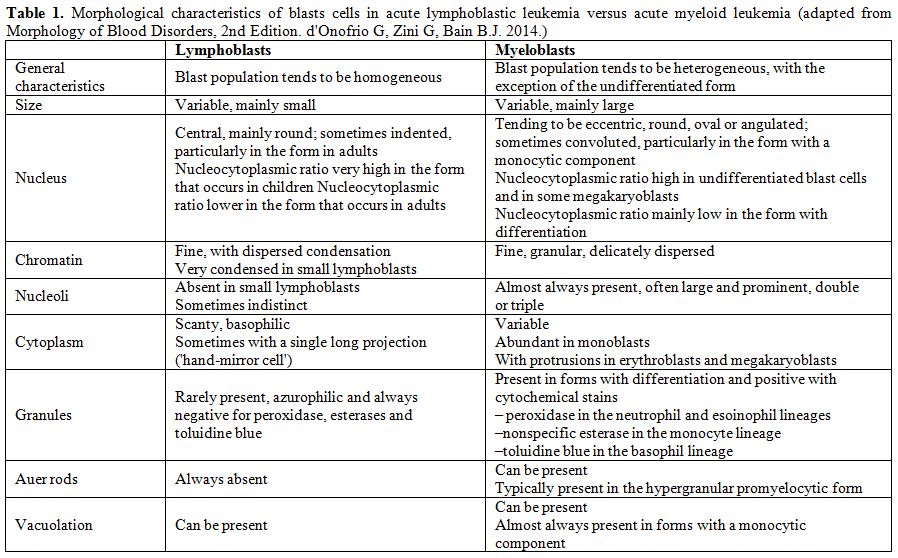

Table 1. Morphological characteristics of

blasts cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia versus acute myeloid

leukemia (adapted from Morphology of Blood Disorders, 2nd Edition. d'Onofrio G, Zini G, Bain B.J. 2014). |

From the morphological point of view, there are no

reproducible criteria to distinguish between B- and T-lineage ALL. It

can also be difficult to distinguish B-lineage lymphoblasts from normal

B-lineage lymphoid precursors, known as hematogones, which are observed

in the peripheral blood in various conditions, including primary

myelofibrosis and in children in the phase of recovery following

chemotherapy.[7] Hematogones typically have an even

higher nucleocytoplasmic ratio than lymphoblasts, with more homogeneous

chromatin and a complete absence of visible nucleoli. Hematogones can

also express the CD10 antigen, but can be distinguished from blast

cells of B ALL by other immunophenotypic features, being characterised

by regular, orderly acquisition and loss of B-lineage antigens; they

can also be distinguished from mature lymphocytes by their weak

expression of CD45 and, sometimes, by the expression of CD34.[7]

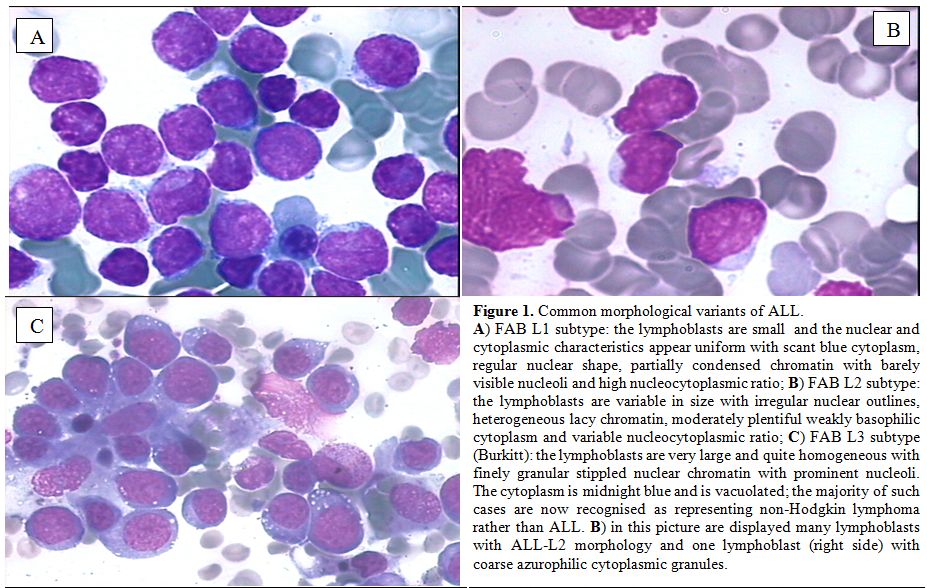

The bone marrow morphology of ALL is however quite variable as previously indicated in the FAB classification (Figures 1-2).

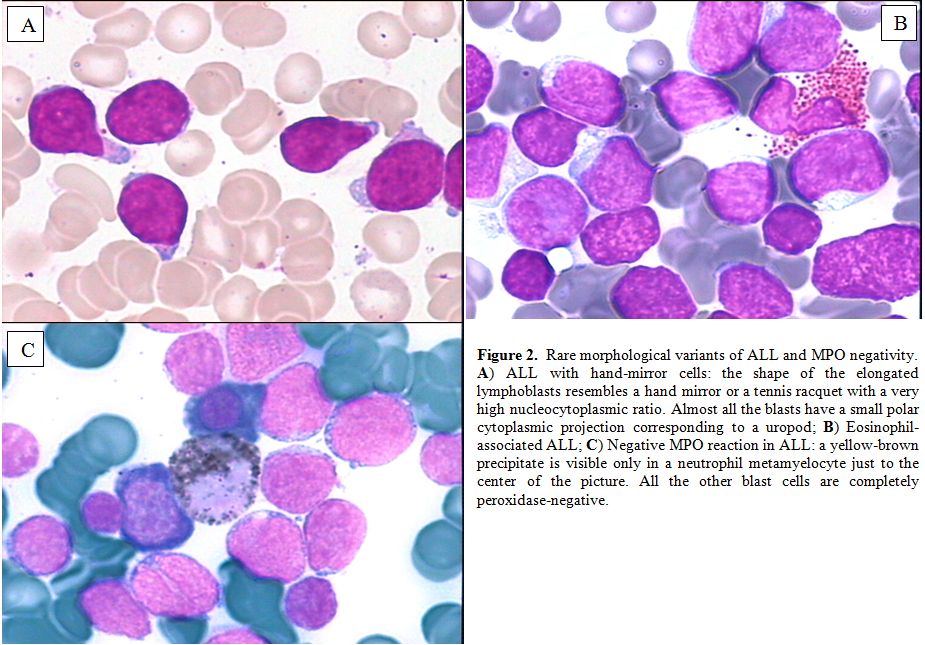

Rare morphological variants are: ALL with “hand-mirror cells”, i.e. the

shape of the cells resembles a hand mirror or a tennis racquet (Figure 2A);

granular ALL, with presence of azurophilic cytoplasmic granules which

vary in number, size and shape. Cytochemically, these blasts have

negative peroxidase reactions and variable periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)

positivity; Sudan black B is sometimes weakly positive;[8]

ALL with mature cells that are nearly indistinguishable from mature

lymphoid neoplasms and require expert observers for accurate

morphological identification;[9] ALL associated with hypereosinophilia (Figure 2B). By definition, ALL blasts are negative for myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Figure 2C)

and other myeloid cytochemical reactions. According to the FAB

criteria, acute (leukemias with at least 3% MPO-positive blasts in BM

should be classified as myeloid. However, low level MPO positivity

without expression of other myeloid markers is detectable by means of

electron microscopy in rare ALL cases. True MPO+ ALL is discussed below

in the mixed lineage acute leukemias section. The acid phosphatase

reaction correlates with the lysosome content; it is useful for

identifying T-ALL blasts which show focal paranuclear positivity in

more than 80% of cases. Lymphoblasts may react with non-specific

esterases with a strong positivity in the Golgi zone with variable

inhibition with sodium fluoride. The B lymphoblasts in FAB L3/Burkitt

ALL show an intense cytoplasmic positivity to methyl green pyronine,

while the vacuoles stain strongly with Oil red O, thus demonstrating

their lipid content. The role of cytochemistry in differentiating ALL

from AML is limited and is mainly of historical interest, since these

tests have now been superseded by the far more objective results

provided by the immunophenotyping.

|

Figure 1. Common morphological variants of ALL.

A)

FAB L1 subtype: the lymphoblasts are small and the nuclear and

cytoplasmic characteristics appear uniform with scant blue cytoplasm,

regular nuclear shape, partially condensed chromatin with barely

visible nucleoli and high nucleocytoplasmic ratio; B) FAB L2 subtype:

the lymphoblasts are variable in size with irregular nuclear outlines,

heterogeneous lacy chromatin, moderately plentiful weakly basophilic

cytoplasm and variable nucleocytoplasmic ratio; C) FAB L3 subtype

(Burkitt): the lymphoblasts are very large and quite homogeneous with

finely granular stippled nuclear chromatin with prominent nucleoli. The

cytoplasm is midnight blue and is vacuolated; the majority of such

cases are now recognised as representing non-Hodgkin lymphoma rather

than ALL. B) in this picture are displayed many lymphoblasts with

ALL-L2 morphology and one lymphoblast (right side) with coarse

azurophilic cytoplasmic granules. |

|

Figure 2. Rare morphological variants of ALL and MPO negativity.

A)

ALL with hand-mirror cells: the shape of the elongated lymphoblasts

resembles a hand mirror or a tennis racquet with a very high

nucleocytoplasmic ratio. Almost all the blasts have a small polar

cytoplasmic projection corresponding to a uropod;

B)

Eosinophil-associated ALL; C) Negative MPO reaction in ALL: a

yellow-brown precipitate is visible only in a neutrophil metamyelocyte

just to the center of the picture. All the other blast cells are

completely peroxidase-negative.

|

Diagnostic Morphology and Cytochemistry

Immunophenotyping by means of multi-channel flow cytometry (MFC) has

become the standard procedure for ALL diagnosis and subclassification,

and was also developed as useful tool for the detection and monitoring

of minimal residual disease (MRD, reviewed elsewhere in this issue).

The consensus by European Group for the Immunological characterization

of leukaemias (EGIL) is that a threshold of 20% should be used to

define a positive reaction of blast cells to a given monoclonal

antibody, except for MPO, CD3, CD79a and TdT, which are considered

positive at the 10% level of expression.[10,11] More

recently, novel MFC strategies were developed by the EuroFlow

consortium to ensure accurate methodologies through all MFC steps, in

order to guarantee the reproducibility of diagnostic tests.[12,13]

To summarize the diagnostic issue, roughly 75-80% of cases of adult ALL

are of B-cell lineage and 20-25% belong to the T-cell lineage.

Immunophenotype of B-lineage ALL

In

B-lineage ALL the most important markers for diagnosis, differential

diagnosis and subclassification are CD19, CD20, CD22, CD24, and CD79a.

The earliest B-lineage markers are CD19, CD22 (membrane and cytoplasm)

and CD79a.[14,15] A positive reaction for any two of

these three markers, without further differentiation markers,

identifies pro-B ALL (EGIL B-I subtype) (Figure 3A).

The presence of CD10 antigen (CALLA) defines the "common" ALL subgroup

(EGIL B-II subtype). Cases with additional identification of

cytoplasmic heavy mu chain constitute the pre-B group (EGIL B-III

subtype) (Figure 3B), whereas the presence of surface immunoglobulin light chains defines mature B-ALL (EGIL B-IV subtype). Among

other B-cell markers, B-I and B-II ALL are often CD24 positive and 4G7

(pro- and pre-B surrogate light chain specific MoAb) positive;[16]

surface CD20 and CD22 are variably positive beyond stage B-I; CD13 and

CD33 myeloid/cross lineage antigen can be expressed, as well as the

CD34 stem cell antigen, particularly in Ph+ (Philadelphia

chromosome-positive) ALL (often B-II with CD34, CD38, CD25 and

CD13/33), but myeloid-specific CD117 should not be present and can be

used to differentiate further between ALL and rare myeloid leukaemias

with negative MPO expression. Pro-B ALL with t(4;11)/MLL rearrangements

is most often myeloid antigen-positive disease (including expression of

CD15). TdT expression is usually lost in B-IV subgroup. T-cell markers

are usually not expressed in B-lineage ALL but a CD19+ subset is

concurrently CD2+. Loss of surface adhesion molecules has been

described.[17]

|

|

Figure

3. Examples of ALL immunophenotype.

A) Pro-B ALL: lymphoblasts are CD19, CD34, CD22, TdT and Cy CD79a positive and CD10 negative;

B)

Pre-B ALL: lymphoblasts are CD22, CD34, CD19, TdT, cytoplasmic

(Cy)CD79a, CD10 and Cy mμ positive; C) Cortical/thymic T-ALL:

Lymphoblasts are cyCD3, CD7, TdT, CD5, and CD1a positive.

|

Immunophenotype of T-lineage ALL

T-cell ALL

constitutes approximately 25% of all adult cases of ALL. T-cell markers

are CD1a, CD2, CD3 (membrane and cytoplasm), CD4, CD5, CD7 and CD8.

CD2, CD5 and CD7 antigens are markers of the most immature T-cell

cells, but none of them is absolutely lineage-specific, so that the

unequivocal diagnosis of T-ALL rests on the demonstration of

surface/cytoplasmic CD3. In T-ALL the expression of CD10 is quite

common (25%) and not specific; CD34 and myeloid antigens CD13 and/or

CD33 can be expressed too. Recognized T-ALL subsets are the following:

pro-T EGIL T-I (cCD3+, CD7+), pre-T EGIL T-II (cCD3+, CD7+ and

CD5/CD2+), cortical T EGIL T-III (cCD3+, Cd1a+, sCD3+/-) and mature-T

EGIL T-IV (cCD3+, sCD3+, CD1a-). Finally, a novel subgroup that was

recently characterized is represented by the so called ETP-ALL (Early-T

Precursor), which shows characteristic immunophenotypic features,

namely lack of CD1a and CD8 expression, weak CD5 expression, and

expression of at least one myeloid and/or stem cell marker.[18]

Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia

With

currently refined diagnostic techniques the occurrence of acute

leukemia of ambiguous cell lineage, i.e. mixed phenotype acute leukemia

(MPAL) is relatively rare (<4%).[19] These cases

express one of the following feature: 1) coexistence of two separate

blast cell populations (i.e. T- or B-cell ALL plus either myeloid or

monocytic blast cells, 2) single leukemic population of blast cells

co-expressing B- or T-cell antigens and myeloid antigens, 3) same plus

expression of monocytic antigens. For myelo-monocytic lineage useful

diagnostic antigens are MPO or nonspecific esterase, CD11c, CD14, CD64

and lysozyme; for B-lineage CD19 plus CD79a, cytoplasmic CD22 and CD10

(one or two of the latter according to staining intensity of CD19) and

for T-lineage cytoplasmic or surface CD3. Recognized entities include

Ph+ MPAL (B/myeloid or rarely T/myeloid), t(v;11q23;MLL rearranged

MPAL, and genetically uncharacterized B or T/myeloid MPAL. Very rare

cases express trilineage involvement (B/T/myeloid). Lack of

lineage-specific antigens (MPO, cCD3, cCD22) is observed in the

ultra-rare acute undifferentiated leukemia. In a recent review of 100

such cases,[20] 59% were B/myeloid, 35% T/myeloid, 4%

B/T lymphoid and 2% B/T/myeloid. Outcome was overall better following

ALL rather than AML therapy.

NK Cell ALL

CD56, a marker of natural killer

(NK) cell differentiation, defines a rare subgroup of about 3% of adult

ALL cases which often display other early T-cell antigens, CD7 CD2 CD5,

and sometimes cCD3.[19] True NK ALL is very rare (TdT+, CD56+, other T

markers negative, unrearranged TCR genes).[21] This diagnosis rely on the demonstration of early NK-specific CD94 or CD161 antigens.

Differential Diagnosis

With

few exceptions, ALL is readily identified by morphological marrow

assessment and MFC evaluation, with no need for additional tests, since

genetics/cytogenetics and genomics are available at a later stage and

cannot be employed for purely diagnostic purposes, even if they add

very useful clinical-prognostic information. Differentiation between

ALL and AML is initially obtained by excluding reactivity to SBB or MPO

stains in ALL cells (<3% positive). On cytochemical evaluation, some

rare ALL cases are SBB positive but MPO and chloroacetate esterase are

negative. True ALL cases that are immunoreactive to MPO or express

detectable levels of MPO mRNA have been described. This can occur in

Ph+ ALL and occasionally in T-lineage ALL.[22] Evaluation of CD117 antigen expression should also be carried out.[23]

Most ALL cases express the nuclear enzyme Terminal deoxynucleotidyl

Transferase (TdT). TdT-negative ALL is uncommonly reported, more in

T-ALL, while it is a rule in L3/Burkitt leukemia. Therefore all

TdT-negative B-precursor ALL cases must be thoroughly investigated to

exclude other aggressive lymphoid neoplasms with leukemic presentation

(blastic mantle cell lymphoma, atypical plasmablastic myeloma, other

high-grade lymphomas).[24,25]

Diagnostic Cytogenetics

Cytogenetics

represents an important step in ALL classification. Conventional

karyotyping can be helpful in the identification of recurrent

translocations, as well as gain and loss of gross chromosomal material;

however, the major limitation of this technique is that in some cases

leukemic cells fail to enter metaphase. However, fluorescence in situ

hybridization (FISH) can enable the detection and direct visualization

of virtually all investigated chromosomal abnormalities in ALL, with a

sensitivity of around 99%. Finally, array-comparative genomic

hybridization (array-CGH, a-CGH) and single nucleotide polymorphisms

(SNP) arrays can permit the identification of cryptic and/or

submicroscopic changes in the genome. Karyotypic changes found in ALL

include both numerical and structural alterations which have profound

prognostic significance.[26-30] With these premises

in mind, the karyotypic changes that occur in ALL can be roughly

subdivided in those associated respectively with a relatively good,

intermediate and poor prognosis (Table 2).[31-34]

However, it must be kept in mind that the incidence of certain

aberrations is very low, and that for some of them, the prognostic

impact can be strongly affected by the type and intensiveness of

therapy administered.

|

|

Table 2. Cytogenetics and prognosis in Ph-negative ALL.

Two karyotype-related prognostic classifications of Ph-negative ALL, as derived from two recent clinical series [31,32].

Definition of risk groups is according to the SWOG study, ranging from

<30% for the very high risk group to 50% and greater for the

favorable subtypes. Some differences are observed in the normal and

“other” karyotypic subgroups, which are assigned to the next better

category in the SWOG study compared to MRC-ECOG. It is necessary to

note that 9p deletions are not always associated with a favorable

prognosis. In a study identifying 18 such cases, survival was short and

comparable to Ph+ ALL [33].

|

Cytogenetic/Genetic Risk Groups

Among

the good prognosis aberrations, it is worth mentioning del(12p) or

t(12p)/t(12;21)(p13;q22) in B-lineage ALL, and t(10;14)(q24;q11) in

T-ALL. These abnormalities are relatively rare in adults compared with

childhood ALL.

Aberrations associated with an intermediate-risk

comprise the normal diploid subset plus cases with hyperdiploidy and

several other recurrent or random chromosomal abnormalities.

Other

aberrations, i.e. those with isolated trisomy 21, trisomy 8, and

perhaps del(6q) and t(1;19)(q23;p13)/E2A-PBX1 may constitute an

intermediate-high risk group; recent evidence suggests that the dismal

outcome previously reported for the t(1;19)(q23;p13)/E2A-PBX1 is

overcome by current therapeutic approaches.[35,36] Other recently identified aberrations in the intermediate high-risk group are represented by iAMP21[37] and IGH rearrangements, including CRLF2.[38]

Finally,

patients with t(9;22)(q34;q11)or BCR-ABL1 rearrangements or a positive

FISH test (Ph+ ALL), t(4;11)(q21;q23) or MLL rearrangements at 11q23,

monosomy 7, hypodiploidy/low hypodiploidy (and the strictly related

near triploid group) fall into the poor-risk cytogenetic category, with

an overall disease-free survival (DFS) rate of about 25%, or 10% in the

case of Ph+ ALL prior to the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors

(TKI).[39-42] Ph+ ALL may constitute 25-50% of CD10+

common or pre-B ALL cases and represent the most frequent abnormality

in the adult/elderly, being detected in more than 50% of cases in 6th decade of life.[43] Secondary chromosome abnormalities in addition to t(9;22)(q34;q11) may worsen the prognosis;[44] however, this is as yet unproven in TKI era.[45]

Currently, the most unfavorable group within cases with known

genetic/molecular aberration is represented by t(4;11)(q21;q23) +

MLL1-rearranged ALL, for which outcome is very poor unless allogeneic

transplantation is adopted.[46]

Some other

karyotypes are unique to specific ALL syndromes. Translocations

involving chromosome 8 (MYC gene), such as t(8;14)(q24;q32) (90% of

cases), t(8;22)(q24;q11)(10% of cases), and t(2;8) (rarely observed),

are virtually present in 100% of cases of mature B-ALL with L3/Burkitt

morphology and clonal surface immunoglobulins. Typical cytogenetic

aberrations are also found in T-lineage ALL.[47] The

most frequent involve 14q11 breakpoints e.g. t(10;14)(q24;q11),

t(11;14)(p13;q11), or other. The presence of t(8;14) with breakpoints

at q24;q11 (q24;q32 in B-ALL) in T-ALL is associated with a

lymphomatous, aggressive presentation.[48,49]

New Genetics and Genomics in ALL

The

integration of results of several techniques, i.e. gene expression

profiling (GEP), SNP array analysis, and currently next-generation

sequencing (NGS), have permitted a better definition of the molecular

scenario of ALL and the identification of a constellation of novel

mutations; as for the latter, however, caution must be shown, since

while the biological role has been elucidated for some, while further

investigation is required for others. These findings are detailed below

(Tables 3, 4).

|

|

Table 3. Identification of novel lesions by integrated molecular genetics. |

|

|

Table 4. Summary of recurrent genetic lesions and mutations in T-ALL. |

B-lineage ALL: IKZF1, encoding for the transcription factor Ikaros, is frequently disrupted in BCR/ABL+ ALL (80% of cases). IKZF1 deletions, that can be different in size, are predictors of poor outcome in Ph+ ALL,[50-52] as well as in non-Ph+ ALL.[53-55]

Deregulated overexpression of CRLF2 (CRLF2), found exclusively in 5-10% B-ALL cases without known molecular rearrangements[56,57] is usually sustained by two types of aberrations: a rearrangement that involves CRLF2 and the Ig heavy chain locus (IGH@-CRLF2) or an interstitial PAR1 deletion that juxtaposes intron 1 of P2RY8 to the coding region of CRLF2 itself. More rarely, CRLF2 mutations can be detected. -CRLF2 can be detected together with IKZF1 deletion in Ph-negative ALL patients and with JAK mutations (JAK1 or JAK2) or IL7R mutations; furthermore, they are identified in roughly 50% of children with Down syndrome;[55,58] although some contrasting results have been reported, its presence correlates with an overall poor outcome.[54,55]

By the integration of genome-wide technologies, the “BCR/ABL-like” subgroup has been suggested/identified in both the adult[59,60] and pediatric populations[61,62]

and it accounts for about 15% of B-ALL cases. This subgroup is

characterized by a gene expression signature that is similar to that of

BCR/ABL+ patients, frequent detection of IKZF1 deletions and CRLF2

rearrangements and adismal outcome. NGS has revealed the presence of

mutations and/or rearrangements activating tyrosine kinases, i.e IGH-CRLF2, NUP214-ABL1 rearrangements, in-frame fusions of EBF1-PDGFRB, BCR-JAK2 or STRN3-JAK2 and cryptic IGH-EPOR rearrangements.[63]

The recognition of this subgroup is of relevance, because of the poor

prognosis observed. Open issues are represented by difficulty in

detecting them with techniques other than gene expression profiling,

which is not routinely performed in all centers, and by the fact that

there is not a recurrent common lesion underlying the signature

identified. With this in mind, it is plausible that the use of TKIs

and/or mTOR inhibitors might be of benefit in these patients, as

suggested by xenograft models.[64,65]

Hypodiploid ALL, regarded as a poor prognosis group, has been extensively evaluated in pediatric ALL:[66] NGS proved that lesions involving receptor tyrosine kinases and RAS signaling (i.e. NRAS, KRAS, FLT3 and NF1)

can be detected in up to 70% of near haploid cases, whereas low

hypodiploid cases are characterized by lesions involving members of the

Ikaros family, particularly IKZF2, and by TP53

disruptions, that can be identified in 91.2% of these cases. In adult

ALL, these cases are characterized by nonrandom chromosomal losses and

the CDKN2A/B locus deletion as sole recurrent abnormality; as already reported in children, these cases frequently harbor TP53 mutations.[67]

TP53 disruption has been also recently evaluated in childhood and adult ALL. In children[68-71]

this is detected in 6.4% and 11.1% of relapsed B-ALL and T-ALL cases,

and, in a smaller minority of cases, also at diagnosis. A correlation

with poorer outcome has been shown. In adults, TP53

mutations are identified at diagnosis in 8.2% of cases (11.1% T-ALL and

6.4% B-ALL), and are preferentially identified in cases without

molecular aberrations, where they are detected in 14% of cases, and are

associated with refractoriness to chemotherapy.

Other lesions identified by NGS in B-lineage ALL, are represented by mutations in CREBBP and its paralogue, EP300 (p300),[72] which were identified in the relapse samples and appear to be more frequent in hyperdiploid relapsed cases.[73] Similarly, NT5C2

mutations, which confer increased enzymatic activity on the NT5C2

protein, which normally dephosphorylates nucleoside analogs, such as

mercaptopurine, used in consolidation and maintenance therapy, have

been described.[74] Results are summarized in Table 3.

T-lineage ALL:

In T-ALL, well-recognized aberrations include the T-cell receptor (TCR)

gene rearrangements, chromosomal deletions, and focal gene deletions (Table 4).[75-83]

Moreover, chromosomal rearrangements can also lead to in-frame fusion

genes encoding chimeric proteins with oncogenic properties such as PICALM-MLLT10, NUP214-ABL1 fusion formed on episomes, EML-ABL1, SET-NUP214 fusion and MLL gene rearrangements with numerous different partners. The prognostic significance of these lesions is uncertain.

Furthermore,

the ETP subgroup and/or myeloid-like subgroup emerged as a grey zone

between AML and T-ALL by applying genome-wide technologies.[18,84,85]

Initially, the reported incidence of this subgroup was established at

around 10% of T-ALL cases; however, with the better recognition of

these cases, its frequency is likely to be higher. Immunophenotype is

characterized by an early T-cell phenotype and co-expression of at

least one myeloid marker, while at the transcriptional level they have

a stem-cell like profile with overexpression of myeloid transcription

factors (including CEBPA, CEBPB, CEBPD),

and a set of micro-RNAs (miR-221, miR-222 and miR-223). NGS has

highlighted the presence of mutations usually found in acute myeloid

leukemia (IDH1, IDH2, DNMT3A, FLT3 and NRAS),[86] as well mutations in the ETV6 gene. Finally, these cases rarely harbor NOTCH1 mutations.[87] Overall, prognosis is poor in these cases.

A large set of mutations (Table 4) has been identified in T-ALL by re-sequencing and NGS: they include NOTCH1, FBW7, BCL11B, JAK1, PTPN2, IL7R and PHF6,

beyond those identified in ETPs; some of them have recognized

prognostic significance, whereas for others further studies are

required. In fact, NOTCH1 and/or FBW7 mutations,

which occur in more than 60% and about 20% of cases, respectively, are

usually associated with a favorable outcome. In the light of this, a

prognostic model has been recently proposed, defining as low-risk

patients those who harbor NOTCH1 and FBW7 mutations, and as high risk those without these mutations or with lesions involving RAS/PTEN.[83,88-91] At variance, JAK1

mutations, which increase JAK activity and alter proliferation and

survival have been associated with chemotherapy refractoriness and

should be considered as poor prognostic markers.[92-94]

Finally,

another group of mutations/lesions is possibly involved in

leukemogenesis, but their prognostic impact is either unknown or

absent. They include: 1) BCL11B lesions, which can induce a developmental arrest and aberrant self-renewal activity;[95,96] 2) PTPN2

- a negative regulator of tyrosine kinases-, mutations, often detected

in TLX1 overexpressing cases, T-ALL, NUP214-ABL+ patients and JAK1 mutated cases;[97,98] 3) mutations in IL7Ralpha, that lead to constitutive JAK1 and JAK3 activation and enhancement of cell cycle progression;[99,100] 4) PHF6 mutations;[101,102] 5) mutations in PTPRC, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase CD45, usually detected in combination with activating mutations of IL7R, JAK1 or LCK, and associated with downregulation of CD45 expression;[103] 6) mutations in CNOT3, presumed to be a tumor suppressor; 7) mutations of RPL5 and RPL10, which impair ribosomal activity.[104] Lastly, similarly to what is observed in relapsed B-ALL, NT5C2 mutations.[105]

Concluding Remarks

Due

to the reviewed evidence and the complexity of all the issues at play,

it is recommended that adult patients with ALL should be treated within

prospective clinical trials, which is the best way to ensure both

diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy. In the context of a

modern risk- and subset-oriented therapy, the early diagnostic work-up

is of the utmost importance and therefore needs to be carried out by

well trained and highly experienced personnel (Figure 4).

As a first step, it is mandatory to differentiate rapidly Ph+ from

Ph-ALL and to distinguish between major immunophenotypic subsets in the

latter group. The remaining diagnostic elements are available at a

later stage and permit a proper identification and treatment of the

several disease and risk entities. Ongoing research will permit the

further definition of novel subgroups with prognostic significance.

|

|

Figure 4. Diagnosis and subclassification of adult ALL.

To

confirm diagnosis and obtain clinically useful information, it is

necessary to 1) differentiate rapidly Ph-positive ALL from

Ph-negative ALL in order to allow an early introduction of

tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the former subset, 2) distinguish between

different clinico-prognostic Ph- ALL subsets, and 3) clarify diagnostic

issues related to the application of targeted therapy and risk-/minimal

residual disease (MRD)-oriented therapy. The early diagnostic phase

must be completed within 24-48 hours. Additional test for

cytogenetics/genetics, genomics and MRD rely on collection, storage and

analysis of large amounts of diagnostic material, and are usually

available at later time-points during therapy, however before taking a

decision for allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT). All this

requires a dedicated laboratory, and is best performed within a

prospective, well coordinated clinical trial.

|

References

- Vardiman

JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute

leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 2009;114:937-951. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262

- Bennett

JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. French-American-British (FAB

Cooperative Group). Proposals for the classification of the acute

leukaemias. Br J Haematol 1976; 33:451-458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x PMid:188440

- Bennett

JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. The morphological classification of

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: concordance among observers and clinical

correlations. Br J Haematol 1981; 47:553-561. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1981.tb02684.x PMid:6938236

- Jaffe

ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. Introduction an overview of the

classification of the lymphoid neoplasms. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E,

Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic

and lymphoid tissue. IARC: Lyon

2008;158-166. PMid:18283093

- Lai

R, Hirsch-Ginsberg CF, Bueso-Ramos C. Pathologic diagnosis of acute

lymphocytic leukemia .Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.2000;14:1209-1235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70183-0

- d'Onofrio

G, Zini G, BainBJ (Translator). Morphology of Blood Disorders, 2nd

Edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. ISBN: 978-1-118-44260)

- Sevilla DW, Colovai AI, Emmons FN, et al. Hematogones: a review and update. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:10-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10428190903370346 PMid:20001239

- Stein

P, Peiper S, Butler D, et al. Granular acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am

J Clin Pathol 1983;80:545.PMid:6578676

- Gassmann

W, Löffler H, Thiel E, et al. Morphological and cytochemical findings

in 150 cases of T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults.

German Multicentre ALL Study Group (GMALL). Br J Haematol 1997;

97:372-382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2171.x PMid:9163604

- Bene

MC, Castoldi G, Knapp W, et al. Proposals for the immunological

classification of acute leukemias. European Group for the Immunological

Characterization of Leukemias (EGIL). Leukemia

1995;9:1783-1786. PMid:7564526

- Béné

MC, Nebe T, Bettelheim P, et al. Immunophenotyping of acute leukemia

and lymphoproliferative disorders: a consensus proposal of the European

LeukemiaNet Work Package 10. Leukemia 2011;25:567-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.312 PMid:21252983

- Kalina

T, Flores-Montero J, van der Velden VH, et al. EuroFlow standardization

of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols.

Leukemia 2012;26:1986-2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.122 PMid:22948490 PMCid:PMC3437409

- van

Dongen JJ, Lhermitte L, Böttcher S, et al. EuroFlow antibody panels for

standardized n-dimensional flow cytometric immunophenotyping of normal,

reactive and malignant leukocytes. Leukemia 2012;26:1908-1975. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.120 PMid:22552007 PMCid:PMC3437410

- Coustan-Smith

E, Behm FG, Sanchez J, et al. Immunological detection of minimal

residual disease in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia..Lancet

1998;351:550-554. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10295-1

- Janossy

G, Coustan-Smith E, Campana D. The reliability of cytoplasmic CD3 and

CD22 antigen expression in the immunodiagnosis of acute leukemia: a

study of 500 cases. Leukemia 1989;3:170-181 PMid:2465463

- Lenormand

B, Bene MC, Lesesve JF, et al. PreB1 (CD10-) acute lymphoblastic

leukemia: immunophenotypic and genomic characteristics, clinical

features and outcome in 38 adults and 26 children. The Groupe dEtude

Immunologique des Leucemies. Leuk Lymphoma

1998;28:329-342. PMid:9517504

- Geijtenbeek

TB, van Kooyk Y, van Vliet SJ, et al. High frequency of adhesion

defects in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood

1999;94:754-764. PMid:10397743

- Coustan-Smith

E, Mullighan CG, Onciu M, et al: Early T-cell precursor leukaemia: a

subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol

2009;10:147-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70314-0

- Vardiman

JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute

leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 2009;114:937-951. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262 PMid:19357394

- Matutes

E, Pickl WF, Van't Veer M, et al. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia:

clinical and laboratory features and outcome in 100 patients defined

according to the WHO 2008 classification. Blood 2011;117:3163-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-10-314682 PMid:21228332

- Paietta

E, Neuberg D, Richards S, et al. Rare adult acute lymphocytic leukemia

with CD56 expression in the ECOG experience shows unexpected phenotypic

and genotypic heterogeneity. Am J Hematol 2001;66:189-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1096-8652(200103)66:3<189::AID-AJH1043>3.0.CO;2-A

- Kantarjian

HM, Hirsch-Ginsberg C, Yee G, et al. Mixed-lineage leukemia revisited:

acute lymphocytic leukemia with myeloperoxidase-positive blasts by

electron microscopy. Blood

1990;76:808-813. PMid:2166608

- Hans

CP, Finn WG, Singleton TP, et al. Usefulness of anti-CD117 in the flow

cytometric analysis of acute leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol

2002;117:301-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1309/RWCG-E5T9-GU95-LEWE PMid:11863227

- Faber

J, Kantarjian H, Roberts MW, Keating et al. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Pathol Lab Med

2000;124:92-97 PMid:10629138

- Zhou

Y, Fan X, Routbort M, et al Absence of terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase expression identifies a subset of high-risk adult

T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma.Mod Pathol 2013;26:1338-1345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.78 PMid:23702731

- Pui

CH, Crist WM, Look AT. Biology and clinical significance of cytogenetic

abnormalities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood

1990;76:1449-1463. PMid:2207320

- Secker-Walker

LM, Prentice HG, et al. Cytogenetics adds independent prognostic

information in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on MRC trial

UKALL XA. MRC Adult Leukaemia Working Party. Br J Haematol

1997;96:601-610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2053.x PMid:9054669

- Group

Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Cytogenetic abnormalities in

adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic

findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Français de

Cytogénétique Hématologique.. Blood 1996;88:3135-314.

- Wetzler

M, Dodge RK, Mrozek K, et al. Prospective karyotype analysis in adult

acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the cancer and leukemia Group B

experience. Blood 1999;93:3983-3993. PMid:10339508

- Kolomietz

E, Al-Maghrabi J, Brennan S, et al. Primary chromosomal rearrangements

of leukemia are frequently accompanied by extensive submicroscopic

deletions and may lead to altered prognosis. Blood 2001;97:3581-3588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V97.11.3581 PMid:11369654

- Moorman

AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic

factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of

cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council

(MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial.

Blood 2007;109:3189-3197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912 PMid:17170120

- Pullarkat

V, Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR. Impact of

cytogenetics on the outcome of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia:

results of Southwest Oncology Group 9400 study. Blood

2008;111:2563-2572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-10-116186 PMid:18156492 PMCid:PMC2254550

- Nahi

H, Hagglund H, Ahlgren T, et al. An investigation into whether

deletions in 9p reflect prognosis in adult precursor B-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia: a multi-center study of 381 patients.

Haematologica 2008;93:1734-1738. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.13227 PMid:18728022

- Charrin

C, Thomas X, Ffrench M, et al. A report from the LALA-94 and LALA-SA

groups on hypodiploidy with 30 to 39 chromosomes and near-triploidy: 2

possible expressions of a sole entity conferring poor prognosis in

adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Blood 2004;104:2444-2451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-04-1299 PMid:15039281

- Felice

MS, Gallego MS, Alonso CN, et al. Prognostic impact of t(1;19)/

TCF3-PBX1 in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the context of

Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster-based protocols. Leuk Lymphoma

2011;52:1215-1221. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2011.565436 PMid:21534874

- Burmeister

T, Gökbuget N, Schwartz S, Fischer L, Hubert D, Sindram A, Hoelzer D,

Thiel E. Clinical features and prognostic implications of TCF3-PBX1 and

ETV6-RUNX1 in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica

2010;95:241-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2009.011346 PMid:19713226

PMCid:PMC2817026

PMCid:PMC2817026

- Harrison

CJ, Moorman AV, Schwab C, et al. An international study of

intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21): cytogenetic

characterization and outcome. Leukemia 2014;28:1015-1021 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2013.317 PMid:24166298

- Moorman

AV, Schwab C, Ensor HM, et al. IGH@ translocations, CRLF2 deregulation,

and microdeletions in adolescents and adults with acute lymphoblastic

leukemia J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:3100-3108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3907 PMid:22851563

- Schardt

C, Ottmann OG, Hoelzer D, Ganser A. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with

the (4;11) translocation: combined cytogenetic, immunological and

molecular genetic analyses. Leukemia

1992;6:370-374. PMid:1375695

- Faderl

S, Albitar M. Insights into the biologic and molecular abnormalities in

adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.

2000;14:1267-1288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70186-6

- Westbrook

CA, Hooberman AL, Spino C, et al. Clinical significance of the BCR-ABL

fusion gene in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Cancer and

Leukemia Group B Study (8762). Blood.

1992;80:2983-2990 PMid:1467514

- Gleissner

B, Gökbuget N, Bartram CR, et al, German Multicenter Trials of Adult

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Study Group. Leading prognostic relevance

of the BCR-ABL translocation in adult acute B-lineage lymphoblastic

leukemia: a prospective study of the German Multicenter Trial Group and

confirmed polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood

2002;99:1536-1543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V99.5.1536 PMid:11861265

- Chiaretti

S, Vitale A, Cazzaniga G, et al.Clinico-biological features of 5202

patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia enrolled in the Italian

AIEOP and GIMEMA protocols and stratified in age cohorts.

Haematologica. 2013;98:1702-1710. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.080432 PMid:23716539 PMCid:PMC3815170

- Rieder

H, Ludwig WD, Gassmann W, et al. Prognostic significance of additional

chromosome abnormalities in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome

positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:678-691.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1968.x PMid:8982045

- Ravandi

F, Jorgensen JL, Thomas DA, et al. Detection of MRD may predict the

outcome of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL treated

with tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus chemotherapy. Blood. 2013 Aug

15;122:1214-1221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-11-466482 PMid:23836561 PMCid:PMC3976223

- Marks

DI, Moorman AV, Chilton L, et al. The clinical characteristics, therapy

and outcome of 85 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and

t(4;11)(q21;q23)/MLL-AFF1 prospectively treated in the

UKALLXII/ECOG2993 trial. Haematologica. 2013;98:945-952. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.081877 PMid:23349309 PMCid:PMC3669452

- Schneider

NR, Carroll AJ, Shuster JJ, et al. New recurring cytogenetic

abnormalities and association of blast cell karyotypes with prognosis

in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a pediatric oncology

group report of 343 cases. Blood.

2000;96:2543-2549. PMid:11001909

- Lange

BJ, Raimondi SC, Heerema N, et al. Pediatric leukemia/lymphoma with

t(8;14)(q24;q11). Leukemia 1992;6:613-618. PMid:1385638

- Parolini

M, Mecucci C, Matteucci C, et al. Highly aggressive T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia with t(8;14)(q24;q11): extensive genetic

characterization and achievement of early molecular remission and

long-term survival in an adult patient. Blood Cancer J. 2014 Jan

17;4:e176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2013.72 PMid:24442205 PMCid:PMC3913941

- Martinelli

G, Iacobucci I, Storlazzi CT, et al: IKZF1 (Ikaros) deletions in

BCRABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are associated with short

disease-free survival and high rate of cumulative incidence of relapse:

a GIMEMA AL WP report. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:5202-5207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6408 PMid:19770381

- Mullighan

CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al: Children's Oncology Group: Deletion of IKZF1

and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2009;

360:470-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0808253 PMid:19129520 PMCid:PMC2674612

- van

der Veer A, Zaliova M, Mottadelli F, et al. IKZF1 status as a

prognostic feature in BCR-ABL1-positive childhood ALL. Blood 2014;

123:1691-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-509794 PMid:24366361

- Kuiper

RP, Waanders E, van der Velden VH, et al: IKZF1 deletions predict

relapse in uniformly treated pediatric precursor B-ALL. Leukemia 2010;

24:1258-1264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.87 PMid:20445578

- Moorman

AV, Schwab C, Ensor HM, et al. IGH@ translocations, CRLF2 deregulation,

and microdeletions in adolescents and adults with acute lymphoblastic

leukemia J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:3100-3108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3907 PMid:22851563

- van

der Veer A, Waanders E, Pieters R, et al. Independent prognostic value

of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2

expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood

2013;122:2622-2629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-10-462358 PMid:23974192 PMCid:PMC3795461

- Mullighan

CG, Collins-Underwood JR, Phillips LA, et al: Rearrangement of CRLF2 in

B-progenitor- and Down syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Nat Genet 2009; 41:1243-1246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.469 PMid:19838194 PMCid:PMC2783810

- Yoda

A, Yoda Y, Chiaretti S, et al. Yoda A, Yoda Y, Chiaretti S, et al:

Functional screening identifies CRLF2 in precursor B-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:252-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911726107 PMid:20018760 PMCid:PMC2806782

- Hertzberg

L, Vendramini E, Ganmore I, et al: Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic

leukemia, a highly heterogeneous disease in which aberrant expression

of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: a report from the

International BFM Study Group. Blood 2010; 115:1006-1117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-08-235408 PMid:19965641

- Haferlach

T, Kohlmann A, Schnittger S, et al: Global approach to the diagnosis of

leukemia using gene expression profiling. Blood 2005; 106:1189-1198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-12-4938 PMid:15878973

- Chiaretti

S, Li X, Gentleman R, et al. Gene expression profiles of B-lineage

adult acute lymphocytic leukemia reveal genetic patterns that identify

lineage derivation and distinct mechanisms of transformation. Clin

Cancer Res. 2005;11:7209-7219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2165 PMid:16243790

- Den

Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al: A subtype of

childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a

genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10:125-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70339-5

- Harvey

RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, et al: Identification of novel cluster groups

in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with

gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number

alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood

2010; 116:4874-4884. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681 PMid:20699438 PMCid:PMC3321747

- Roberts

KG, Morin RD, Zhang J, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and

cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Cancer Cell 2012;22:153-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.005 PMid:22897847 PMCid:PMC3422513

- Maude

SL, Tasian SK, Vincent T, et al. Targeting JAK1/2 and mTOR in murine

xenograft models of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood

2012;120:3510-3518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-03-415448 PMid:22955920 PMCid:PMC3482861

- Roberts

KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions

in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med

2014;371:1005-1015. PMid:25207766

- Holmfeldt

L, Wei L, Diaz-Flores E, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2013;45:242-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.2532 PMid:23334668 PMCid:PMC3919793

- Mühlbacher

V, Zenger M, Schnittger S, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with low

hypodiploid/near triploid karyotype is a specific clinical entity and

exhibits a very high TP53 mutation frequency of 93%. Genes Chromosomes

Cancer 2014;53:524-536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22163 PMid:24619868

- Hof

J, Krentz S, van Schewick, et al: Mutations and deletions of the TP53

gene predict nonresponse to treatment and poor outcome in first relapse

of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011;

29:3185-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8144 PMid:21747090

- Krentz

S, Hof J, Mendioroz A, et al: Prognostic value of genetic alterations

in children with first bone marrow relapse of childhood B-cell

precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2013;27:295-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.155 PMid:22699455

- Chiaretti

S, Brugnoletti F, Tavolaro S, et al: TP53 mutations are frequent in

adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases negative for recurrent fusion

genes and correlate with poor response to induction therapy.

Haematologica 2013;98:e59-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.076786 PMid:23403321 PMCid:PMC3640132

- Stengel

A, Schnittger S, Weissmann S, et al. TP53 mutations occur in 15.7% of

ALL and are associated with MYC-rearrangement, low hypodiploidy and a

poor prognosis. Blood 2014;124:251-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-02-558833 PMid:24829203

- Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Kasper LH, et al: CREBBP mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2011; 471:235-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09727 PMid:21390130 PMCid:PMC3076610

- Inthal

A, Zeitlhofer P, Zeginigg M, et al. CREBB HAT domain mutations prevail

in relapse cases of high hyperdiploid childhood acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:1797-1803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.60 PMid:22388726 PMCid:PMC4194312

- Meyer

JA, Wang J, Hogan LE, et al. Relapse-specific mutations in NT5C2 in

childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2013; 45:290-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.2558 PMid:23377183 PMCid:PMC3681285

- Barber

KE, Martineau M, Harewood L, et al. Amplification of the ABL gene in

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2004;18:1153-1156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2403357 PMid:15057249

- Ferrando

AA, Neuberg DS, Dodge RK, et al. Prognostic importance of TLX1 (HOX11)

oncogene expression in adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukaemia. Lancet 2004;363:535-536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15542-6

- Ballerini

P, Busson M, Fasola S, et al. NUP214-ABL1 amplification in

t(5;14)/HOX11L2-positive ALL present with several forms and may have a

prognostic significance. Leukemia 2005;19:468-470. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2403654 PMid:15674415

- Asnafi

V, Buzyn A, Thomas X, et al. Impact of TCR status and genotype on

outcome in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a LALA-94 study.

Blood 2005;105:3072-3078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-09-3666 PMid:15637138

- Burmeister

T, Gokbuget N, Reinhardt R, Rieder H, Hoelzer D, Schwartz S.

NUP214-ABL1 in adult T-ALL: the GMALL study group experience. Blood

2006;108:3556-3559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-04-014514 PMid:16873673

- Baldus

CD, Burmeister T, Martus P, et al. High expression of the ETS

transcription factor ERG predicts adverse outcome in acute

T-lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4714-4720. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1580 PMid:16954520

- Baldus

CD, Martus P, Burmeister T, et al. Low ERG and BAALC expression

identifies a new subgroup of adult acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia with

a highly favorable outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3739-3745. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5253 PMid:17646667

- Bergeron

J, Clappier E, Radford I, et al. Prognostic and oncogenic relevance of

TLX1/HOX11 expression level in T-ALLs. Blood. 2007;110:2324-2330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-04-079988 PMid:17609427

- Asnafi

V, Buzyn A, Le Noir S, et al: NOTCH1/FBXW7 mutation identifies a large

subgroup with favourable outcome in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia (TALL): a GRAALL study. Blood 2009; 113:3918-3924 http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-10-184069 PMid:19109228

- Chiaretti

S, Messina M, Tavolaro S, et al: Gene expression profiling identifies a

subset of adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with myeloid-like

gene features and over-expression of miR-223. Haematologica 2010;

95:1114-1121. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2009.015099 PMid:20418243 PMCid:PMC2895035

- Coskun

E, Neumann M, Schlee C, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals aberrant

microRNA expression in adult ETP-ALL and functional studies implicate a

role for miR-222 in acute leukemia. Leuk Res 2013;37:647-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2013.02.019 PMid:23522449

- Zhang

J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, Wu G, et al: The genetic basis of early T-cell

precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2012; 481:157-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10725 PMid:22237106 PMCid:PMC3267575

- Van

Vlierberghe P, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Perez-Garcia A, et al: ETV6

mutations in early immature human T cell leukemias. J Exp Med 2011;

208:2571-2579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20112239 PMid:22162831 PMCid:PMC3244026

- Park

MJ, Tak T, Oda M, et al: FBXW7 and NOTCH1 mutations in childhood T cell

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and T cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J

Haematol 2009; 145:198-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07607.x PMid:19245433

- Mansour

MR, Sulis ML, Duke V, et al: Prognostic implications of NOTCH1 and

FBXW7 mutations in adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

treated on the MRC UKALLXII/ECOG E2993 protocol. J Clin Oncol 2009;

27:4352-4356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0996 PMid:19635999 PMCid:PMC2744275

- Ben

Abdelali R, Asnafi V, Leguay T, et al: Group for Research on Adult

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Pediatric-inspired intensified therapy of

adult T-ALL reveals the favorable outcome of NOTCH1/FBXW7 mutations,

but not of low ERG/BAALC expression: a GRAALL study. Blood 2011;

118:5099-5107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-02-334219 PMid:21835957

- Trinquand

A, Tanguy-Schmidt A, Ben Abdelali R, et al. Toward a

NOTCH1/FBXW7/RAS/PTEN-based oncogenetic risk classification of adult

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Group for Research in Adult

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4333-4342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5292 PMid:24166518

- Flex

E, Petrangeli V, Stella L, et al: Somatically acquired Jak1 mutation in

adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med 2008;205:751-758. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20072182 PMid:18362173 PMCid:PMC2292215

- Jeong

EG, Kim MS, Nam HK, et al: Somatic mutations of JAK1 and JAK3 in acute

leukemias and solid cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:3716-3721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4839 PMid:18559588

- Asnafi

V, Le Noir S, Lhermitte L, et al: JAK1 mutations are not frequent

events in adult T-ALL: a GRAALL study. Br J Haematol 2010;148:178-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07912.x PMid:19764985

- Gutierrez

A, Kentsis A, Sanda T, et al: The BCL11B tumor suppressor is mutated

across the major molecular subtypes of T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Blood 2011; 118:4169-4173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-11-318873 PMid:21878675 PMCid:PMC3204734

- Kraszewska

MD, Dawidowska M, Szczepanski T, et al: T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukaemia: recent molecular biology findings. Br J Haematol 2012;

156:303-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08957.x PMid:22145858

- Kleppe

M, Lahortiga I, El Chaar T, et al: Deletion of the protein tyrosine

phosphatase gene PTPN2 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Gen

2010; 42:530-535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.587 PMid:20473312 PMCid:PMC2957655

- Kleppe

M, Soulier J, Asnafi V, et al: PTPN2 negatively regulates oncogenic

JAK1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2011; 117:7090-7098.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-10-314286 PMid:21551237

- Shochat

C, Tal N, Bandapalli OR, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in

interleukin-7 receptor-a (IL7R) in childhood acute lymphoblastic

leukemias. J Exp Med. 2011;208:901-908. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20110580 PMid:21536738 PMCid:PMC3092356

- Zenatti

PP, Ribeiro D, Li W, et al: Oncogenic IL7R gain-of-function mutations

in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2011;

43:932-939. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.924 PMid:21892159

- Van

Vlierberghe P, Palomero T, Khiabanian H, et al: PHF6 mutations in

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.Nat Genet 2010; 42:338-342 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.542 PMid:20228800 PMCid:PMC2847364

- Wang

Q, Qiu H, Jiang H, et al: Mutations of PHF6 are associated with

mutations of NOTCH1, JAK1 and rearrangement of SET-NUP214 in T-cell

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2011; 96:1808-1814. http://dx.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.043083 PMid:21880637 PMCid:PMC3232263

- Porcu

M, Kleppe M, Gianfelici V, et al: Mutation of the receptor tyrosine

phosphatase PTPRC (CD45) in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood

2012; 119:4476-4479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-09-379958 PMid:22438252

- De

Keersmaecker K, Atak ZK, Li N, et al: Exome sequencing identifies

mutation in CNOT3 and ribosomal genes RPL5 and RPL10 in T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2013;45:186-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.2508 PMid:23263491

- Tzoneva

G, Perez-Garcia A, Carpenter Z, et al: Activating mutations in the

NT5C2 nucleotidase gene drive chemotherapy resistance in relapsed ALL.

Nat Med 2013;19:368-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.3078 PMid:23377281 PMCid:PMC3594483

[TOP]

PMCid:PMC2817026

PMCid:PMC2817026