Received: August 9, 2015

Accepted: November 9, 2015

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016005, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.005

This article is available on PDF format at:

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Objective: To identify the pattern of the clinical,

radiological, diagnostic procedures and loss to follow -up of the

diagnosed cases of active tuberculosis (TB) adolescents. Methods: This study was a retrospective analysis of the medical records of 143 adolescents aged 10 to 18 years with tuberculosis who were admitted TB wards of National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (NRITLD) in Tehran, Iran, between March 2006 and March 2011. Results: Of the 143 patients identified, 62.9% were females. Median age of the patients was 16 years. The contact source was identified in 47.5%. The most common presenting symptom was cough (86%).Isolated pulmonary TB (PTB) was detected in 113 patients (79%), 21 patients (14.7%) had extrapulmonary TB (EPTB), and 9 patients (6.3%) had PTB and EPTB. The most common site of EPTB was pleural (14%). The most common radiographic finding was infiltration (61%). Positive acid fast smears were seen in 67.6%. Positive cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. TB) were seen in 44.7%. Positive Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results were seen in 60%.The adolescents aged 15 to 18 years were more likely to lose weight (p=0.001), smear positive (p=0.001), culture positive (p<0.001) and h ave positive PCR results (p=0.009). The type of TB (p=0.017) was a significant factor influencing loss to follow-up. Conclusions: The study has revealed that the clinical and radiological findings of TB in adolescents are combination as identified in children and adults. The TB control programs should pay more attention to prevention and treatment of TB in adolescents. |

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major health problem globally with 8.6 million people identified in 2012 of whom 1.3 million died.[1] Recent data from Iran estimated the incidence rate of TB as 21 cases per 100,000 population in 2012.[2] According to a recent study in South Africa, among 29,478 newly notified TB cases, the incidence rate started to peak in adolescents.[3] Recent studies have shown that adolescents are a susceptible age group with a higher case incidence compared to young children.[4-6] There are few studies on adolescent TB in the literature and reports indicate that many adolescents with active TB are diagnosed during the late stage of the disease.[7] One study performed in Canada showed that the average interval between the beginning of symptoms and diagnosis of TB was 5 months.[8] The delay in the treatment due to delay in diagnosis of TB leads to increase in the infectivity of the infected person in the community as a result of social interactions in this age group. The aim of this study was to evaluate the demographic data, clinical presentations, radiologic features, microbiological findings, site of TB, treatment, and outcome in this age group.

Material and methods

This study was

conducted on all patients aged 10 to 18 years old with a confirmed

diagnosis of TB, who were admitted to TB wards of National Research

Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (NRITLD) in Masih Daneshvari

Medical Center between March 2006 and March 2011. NRITLD is a World

Health Organization (WHO) Cooperative health center for TB and lung

disease, located in Tehran, Iran. NRITLD provides particular care for

TB patients who referred from across the country. As in WHO definition,

adolescents group was defined as any person between ages 10 and 18.[9]

The following data was analyzed in this study: demographic data,

presenting symptoms, radiographic features, bacteriological results,

tuberculin skin test, and treatment, outcome, and drug susceptibility

results. Patients with TB disease were defined in two categories: 1)

Definite TB was defined by identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(M.TB) from the sputum, gastric lavage, body secretions, or surgical

specimens, or the histological appearance of biopsy material

representing TB-affected tissues (caseous necrosis or granulomatous

tubercles). 2) Probable TB was referred as the presence of 3 or more of

the following: symptoms and signs consistent with active TB; abnormal

radiography of TB (hilar lymphadenopathy and/or consolidation); history

of TB contact and either response to TB therapy. Then, cases were

divided into two age groups, 10-14 and 15-18 years.

Tuberculin

skin test (TST) and radiological findings could not be determined for

all patients through the information in the medical files since the

study was retrospective. TB treatment has been started at the time of

diagnosis, as recommended by the WHO guidelines, consisting of

isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide for an initial 2-

month phase followed by isoniazid and rifampin for a maintenance

4-month phase.[10]

SPSS version 21 was used for data analysis.

The Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the level of

significance. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis were used to compare

the relationship between an increase in age and positive acid-fast

smears, and increase in age and cavitary lesions, respectively. A

p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

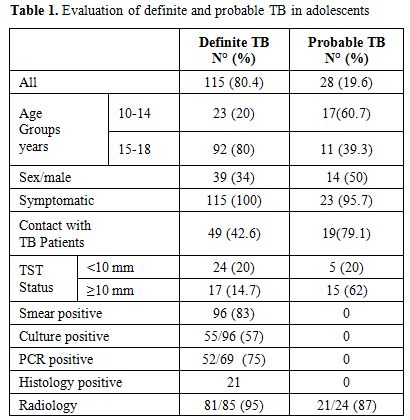

We identified 143 patients with TB, 115 (80.4%) definite TB and 28 (19.6%) probable TB (Table 1).

Ninety (62.9%) were female, and 53 (37.1%) were male. The median age

was 16 years. Of these, 79 (55.2%) were Iranian and 64 (44.8%) Afghan.

Scar of Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine injection was seen in 27

(19%), in 10 (7%) not seen the scar and in 106 (74%) the scar was

unknown. The contact source was identified in 68 cases (47.5%); 24(60%)

in 10-14 years and 44 (42.7%) in 15-18 years old. The difference

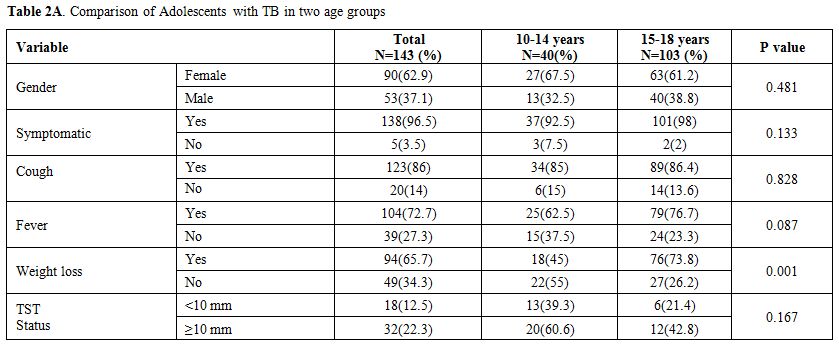

between two age groups is described in Table 2.

Common contact sources were parents 26 (18.2%). HIV was only tested for

56 out of 143 patients, among them two patients (3.5%) were HIV

positive and presented with pulmonary localization.

A TST result

was available in 61 patients. Of these, Thirty-two (22.3%) patients had

induration that exceeded 10mm. There was no significant difference in

TST positivity between two groups. (p-value: 0.167) (Table 2).

However, there may have been some selection bias regarding whose

results were available for TST, making a difference in TST positivity

between the groups.

|

Table 1. Evaluation of definite and probable TB in adolescents |

|

Table 2a. Comparison of Adolescents with TB in two age groups |

|

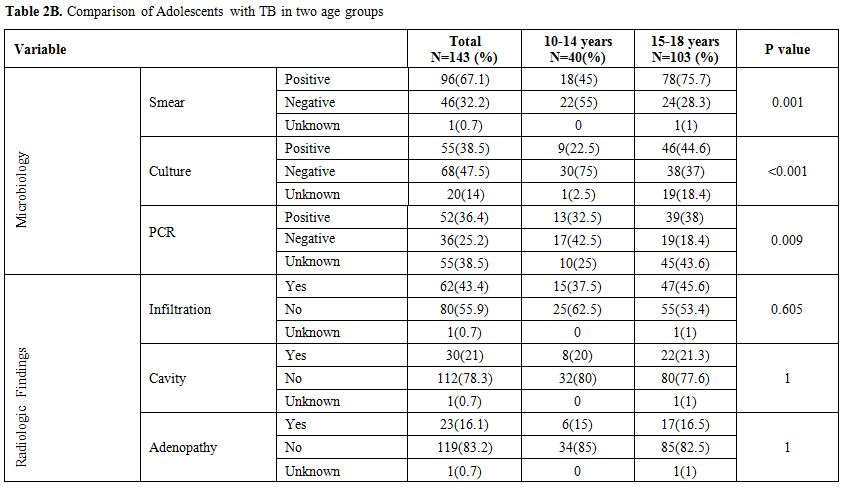

Table 2b. Comparison of Adolescents with TB in two age groups |

Most patients 138 (96.5%) were recognized by presenting

symptomatically. The most common symptoms were a cough 123 (86%), fever

104 (72.7%) and weight loss 94 (65.7%). The median of symptoms duration

was two months. Five patients were asymptomatic at presentation; all of

them had the history of contact, reactive TST and pulmonary involvement

in chest radiographic.

Isolated pulmonary disease occurred in 113

(79%), 21 (14.7%) had extrapulmonary disease, and 9 (6.3%) had

pulmonary TB(PTB) and extrapulmonary TB(EPTB); EPTB distributed

as pleural 20 (14%), central nervous system (CNS) 4 (2.8%), lymph node

1 (0.7%), pleural with peritoneal 2 (1.4%), pleural with skeletal

1 (0.7%), and CNS with lymph node 1 (0.7%).

Positive acid-fast

smears were seen in 96 of 142 patients (67.6%). The most common site of

smear positive was sputum 76 (53%). The smear-positive rate increased

with age (33% at ten years to 76% at 18 years) (Mann-Whitney: p=0.003)

peak age was 16 years (80%) (Figure 1).

Cultures were achieved in 123 patients. Positive cultures for M.TB were

seen in 55 (44.7%); fifty patients with pulmonary disease, one patient

with EP TB and four patients with both disease. Culture-positive rate

increased with age (17% at 10 years to 48% at 18 years) (Mann-Whitney:

p=0.039) (Figure 1). Polymerase

chain reaction (PCR) test of M.TB were performed for 88 patients;

positive PCR was seen in 52 patients (60%). The common site of positive

PCR test was sputum in 38 patients (73%). PCR-positive rate increased

with age (40% at 10 years to 80% at 18 years) (Mann-Whitney: p=0.018) (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Age distribution of adolescents with smear positivity, culture positivity , PCR positivity and with the presence of cavity lesion. |

Twenty-one patients were confirmed as TB cases by a

histological diagnosis (pleural n=14, bronchial n=6, lymph nodes

n=2, bone n=1). Drug susceptibility testing (DST) for M.TB was

performed in 15 patients. Seven patients had susceptible M.TB strains

to all anti-TB drugs, eight patients had isolates of M.TB

drug-resistant: 5 had multidrug-resistant TB (three with resistance to

rifampin and isoniazid, another with additional resistance to

ethambutol, amikacin, and kanamycin), three patients had drug

resistance to isoniazid and one to pyrazinamide.

Radiography

reports were available in 107 patients; 23 cases had chest X-ray, and

84 cases had CT scan reports. Abnormalities were found in 102 (95.3%).

Of these patients, 62 of 102 (61%) had infiltration, 52 of 102 (51%)

had consolidation, 30 (29%) cavity, 25 (24.5%) pleural effusion and 23

(22.5%) adenopathy. Cavitary lesion was increased with age (0 at ten

years to 23% at 18 years) but the difference is not statistically

significant (by Kruskalwallis: p=0.373) (Figure 1)

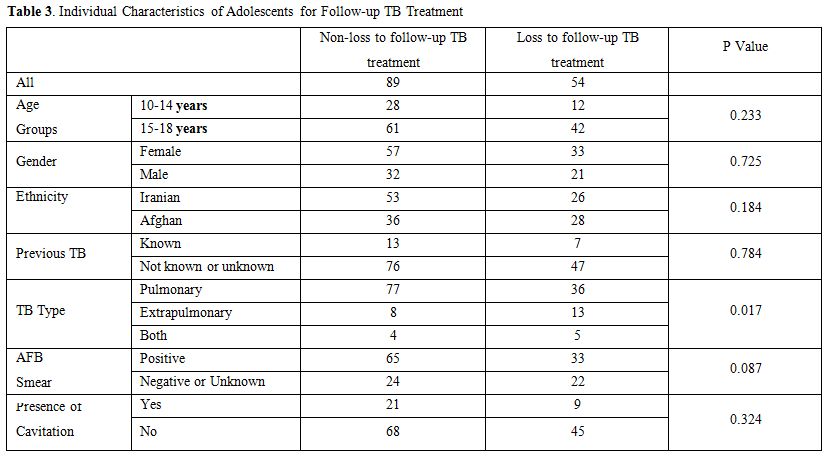

Eighty-nine

patients (61%) had complete follow-up; 71 (49.7%) improvement, 14

(9.8%) relapse, 3 (2.1%) expire and 1 (0.7%) sequelae. Fifty-four (39%)

adolescents identified as a loss to follow-up TB treatment. The

comparison between adolescents loss to follow–up and not were performed

to found if any factors based on our research that influenced loss to

follow–up. A significant statistical difference was found for type TB

(p=0.017) between adolescents identified as a loss to follow–up and not

(Table 3).

Elevation of

AST and ALT enzymes occurred in 9 of 143 patients (6.2%); seven

patients were between 15 and 18 years. However, restored to the normal

range without any disruption of treatment.

|

Table 3. Individual Characteristics of Adolescents for Follow-up TB Treatment |

Discussion

This study reports the epidemiology and characteristics of TB in

adolescents from a developing country. To our knowledge, no similar

study has been reported from other Middle East countries. Clinical and

radiological features of adolescents TB are different from children and

adults. Older adolescents had a severity of TB disease than younger

adolescents.

Adolescents are more frequently

symptomatic.[8,11,12] We also found most patients (96.5%) were

recognized after presenting with symptoms. Isolated PTB and EPTB were

detected in 79.7% and 14.7% of the patients in this study,

respectively. Previous studies detected PTB and EPTB in 22% to 78.6%

and 17% to 35% of the adolescents with TB, respectively.[8,11,12] The

proportion of patients with EPTB compared with those of PTB varies

among countries and depends on host-related factors such as ethnicity,

and associated diseases.[13] In this study, the frequency of EPTB was

closer to the rate in adults (16%) as compared to children (27.3%).[14]

The most common form of EPTB in our adolescents was pleural, similar to

studies conducted in France and Canada.[8,12] This is in contrast to

studies conducted in the USA and South Africa that found the most

common site of EPTB was peripheral lymphadenopathy.[11,15] These

differences propose that the type of EPTB may be specific to

adolescents in different population; more population-based studies in

different geographic regions are required.

Approximately fifty

percent of our adolescents were exposed to a known adult with TB. This

finding shows that contact investigation remains an essential tool for

the control of TB disease. Previous contact investigation may have

prevented these cases of adolescents TB. Positive source cases were

identified in 25–66% of the children with TB in previous

studies.[16-19] In our study, the rate of exposure to known adults with

TB was close to the rate of children with TB. According to some

studies, the history of contact with TB can be determined in 12%-19% of

adult patients.[20-22]

Similar to the study conducted in the US,

we found that adolescents aged 15 to 18 years were more likely to have

smear-positive TB and severity of the disease.[23] An

epidemiological study on age and pathogenesis of TB has revealed that

older adolescents are at higher risk of developing the disease than

younger adolescents after infection with M.TB.[24] Since most of these

age groups have considerable social connections and interactions in

colleges or schools; these patients are more likely to transmit TB to

the community. Therefore, it is important to screen older adolescents

for TB. Studies in children have revealed that the yields of culture

and PCR are higher than that of the smear.[25] Nevertheless, we found

that the rate of smear positivity was higher than that of culture and

PCR. Smear positive /culture negative results may be due to the

presence of nonviable mycobacteria in the sample receiving anti-TB

treatment. The low yields of culture and PCR might be due to low sample

volume. More effort is needed to improve both quality and quantity of

samples to have a better diagnosis of TB in adolescents.[26]

Lymphadenopathy

was the most common radiographic feature in young children.[27] After

puberty, the radiological findings of TB are similar to adults include

parenchymal lesions and cavities.[28] In the present study, the most

common radiologic finding was infiltration, which is similar to studies

conducted in the United States and Brazil.[11,29] In contrast to the

study conducted in France, most patients had mediastinal

lymphadenopathy. However, despite this finding, a notable number of

patients continue to present with a parenchymal lesion in France

study.[12] Although not statistically significant, cavitary lesion rate

increased with age in our study. The studies on adolescent TB in

France,[12] Brazil[21] and South Africa[15] found that the cavity

lesion rate increased with age. Seventy-one percent (n=101) of our

patients were probably preventable through screening immigrants from

Afghanistan (64) and contact investigation (37). Our study was

consistent with the study performed in the US.[11] This finding

demonstrates the importance of developing new strategies for the

prevention and treatment of TB to improve children’s and adolescents’

survival to achieve Millennium Development Goals.[30]

TB patients

who are lost to follow-up are at increased risk of developing

drug-resistant TB and treatment failure that further increases the risk

of TB transmission.[31] In this study, 54 patients (37.7%) were lost to

follow-up after starting treatment. It is necessary to identify the

components of potential behavioral intervention strategies for future

program implementation among adolescents entering and receiving TB

care. Contracting the contingency and peer counseling are two such

intervention methods that have been used in adolescents.[32] Peer

counseling is an adolescent with a successful TB treatment encouraging

a newly diagnosed adolescent patient. Contingency contracting is

improving the desired behavior of adherence to the medical regimen by

providing incentives.[33] It has been suggested that prospective

studies are required to evaluate such strategies to increase adherence

to TB treatment.

Patients with EPTB were more likely to become

lost to follow-up than those with PTB in this study. This result is in

agreement with findings in previous studies.[34,35] However, other

studies have found no relationship between the type of TB and the

successful TB treatment outcome.[36-38] Despite the increasing

proportion of patients with EPTB in many countries, these patients

often receive less priority on the international health system.[39]

Therefore, more attention must be paid to the patients with EPTB, who

are usually neglected in the TB control program.

Directly observed

treatments (DOTs) should be attended to improve treatment compliance.

There is a need to conduct prospective studies on the risk factors of

loss to follow-up in adolescents TB treatment such as inadequate

knowledge about TB, living far from health facilities, and drug side

effects. Only one recent study revealed that the lowest rates of

completing TB treatment were associated with older adolescent age,

ethnicity, parental responsibility, and access to the clinic.[40]

Conclusions

The study has shown that the clinical and radiological findings of TB in adolescents are a combination as identified in children and adults. The data presented in this study have implications for the development of strategies for early screening of TB in high-risk categories, prompt diagnosis of TB, and improving the rate of completion of care among adolescents treated for TB.

Acknowledgment

References

[TOP]