Received: August 14, 2015

Accepted: November 26, 2015

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016009, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.009

This article is available on PDF format at:

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Objectives: Low-dose

cytarabine (LD-AraC) is still regarded as the standard of care in

elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) ‘unfit’ for

intensive chemotherapy. In this study, we reported our experience with

LD-AraC in patients ≥ 70 years old and compared the results to those of

intensive chemotherapy, best supportive care (BSC), or hypomethylating

agents in the same age population. Methods: Between 2000 and 2014, 60 patients received LD-AraC at 20 mg once or twice daily by subcutaneous injection for 10 consecutive days every 4-6 weeks. Results: Complete remission rate with LD-AraC was 7% versus 56% with intensive chemotherapy and 21% with hypomethylating agents. Median overall survival (OS) of patients treated with LD-AraC was 9.6 months with 3-year OS of 12%. Survival with LD-AraC was better than with BSC only (P=0.001). Although not statistically significant, intensive chemotherapy and hypomethylating agents tended to be better than LD-AraC in terms of OS (median: 12.4 months and 16.1 months, respectively). There was no clear evidence that a beneficial effect of LD-AraC was restricted to any particular subtype of patients, except for cytogenetics. There was a trend for a better OS in LD-AraC treated patients in the setting of clinical trials as compared with those treated outside of a clinical trial. Conclusions: Despite a trend in favor of intensive chemotherapy and hypomethylating agents over LD-AraC, no real significant advantage could be demonstrated, while LD-AraC showed a significant advantage comparatively to BSC. All this tends to confirm that LD-AraC can still represent a baseline against which new promising agents may be compared either alone or in combination. |

Introduction

Despite multiple advances in AML therapy, the treatment outcome for

older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is unsatisfactory,

especially for patients in their latter years. As people are living

longer, the incidence of AML is increasing. The treatment outcome for

patients aged 70 years or older has not improved significantly over the

last two decades in spite of improved supportive care. Most of these

patients do not receive intensive chemotherapy either because they

decline or because they are not considered fit enough for such therapy.

The basis on which patients are not considered fit enough for intensive

chemotherapy remains not clear and varies considerably from one

investigator to another. Clearly performance status remains an

important factor in therapy planning. However, evaluation of ‘fitness’

remains unclear. Recent reports have shown that geriatric assessment

methods, with a focus on cognitive and physical function, improve risk

stratification and may inform interventions to improve outcomes for

older AML patients.[1] Others showed that candidacy for intensive therapy should be based on biological features of disease rather than on age.[2]

Although

low-dose cytarabine (LD-AraC) has not been adopted universally, it

still represents a treatment reference (at least in Europe) for

patients considered ‘unfit’ for intensive chemotherapy. LD-AraC was

investigated extensively more than 20 years ago. LD-AraC has been used

in various schedules showing responses that included complete remission

(CR).[3-9] Its mechanism of action is still not

completely clear, acting potentially through cytotoxic action and/or

through induction of apoptosis by differentiation induction.[10,11]

LD-AraC is relatively well tolerated and can be given in an outpatient

care setting. However, it can induce excess cytopenia although this may

be a prerequisite for efficacy. In the literature, 10% to 20% of

patients have been reported to achieve CR.[3-9,12]

Randomized studies between intensive and non-intensive treatments

showed better responses in intensively treated patients, but no

significant differences in terms of survival.[13,14]

LD-AraC has been demonstrated to be more beneficial than best

supportive care and hydroxyurea among patients not fit for intensive

therapy, although fitness was not defined for patients’ age >70

years.[12] LD-AraC therapy still represents a

baseline against which novel drugs may be compared either alone or in

addition to LD-AraC. Currently, the role of lower-intensity regimens is

under active investigations.[12,15-19]

Recent randomized trials comparing DNA hypomethylating agents,

azacitidine or decitabine, with LD-AraC found improved CR rates and

better survival with hypomethylating agents.[15,19]

These

studies urged us on analyzing our series of elderly patients treated

with LD-AraC with the aim to evaluate whether this treatment could

still represent a standard therapy in this patient population to which

new treatments should be compared. We, therefore, evaluated the

efficacy of LD-AraC, in a single institution experience, in patients

aged 70 years or older, and compared it to that of other treatments

received by patients of the same age (intensive chemotherapy, best

supportive care (BSC), and lower intensity therapy based on

hypomethylating agents).

Patients and Methods

Patients:

In total, 234 patients (aged 70 years or older) with newly diagnosed

AML have been seen in the Department of Hematology at Lyon-University

Hospital from 2000 to 2014. From 2000 to 2006, patients with PS ≤2

were considered ‘fit’ by the local physician and received an intensive

treatment approach systematically. No specific criteria for defining

‘fitness’ were used. After 2006, a more ‘personalized’ treatment using

either intensive chemotherapy or lower-intensity therapies (including

LD-AraC, decitabine or azacitidine) based on the clinical judgment of

the treating physician and the availability of clinical trials were

proposed.[20] Most patients older than 70 years

received, therefore, a non-intensive option. Any type of AML (de novo

or secondary) was considered. Acute promyelocytic leukemia and blast

transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia were excluded. Among the 234

patients (aged 70 years or older) with newly diagnosed AML, 60 patients

(16%) received LD-AraC. They were compared to 85 patients treated with

intensive therapy (anthracycline- and cytarabine-based chemotherapy),

34 patients treated with hypomethylating agents (12 by decitabine and

22 by azacitidine), and 43 patients receiving only BSC. The 12

remaining patients received other treatments in the setting of

investigational trials and were not considered for the study.

Treatment:

On entry, patients received LD-AraC 20 mg once or twice daily

(according to physician’s choice) by subcutaneous (sc) injection for 10

consecutive days. Subsequent courses of LD-AraC were administered at

intervals of 4 to 6 weeks. Regarding the control groups, intensive

chemotherapy consisted of a combination of intermediate-dose cytarabine

with an anthracycline. Azacitidine was given at the dose of 75 mg/m2/day for 7 consecutive days by sc injection, and decitabine was administered by intravenous route once daily at 20 mg/m2

for 5 consecutive days. Subsequent courses of these low-intensity

treatments were administered at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks until disease

progression. All clinical trials received approval from the

institutional review board and were conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their written informed

consent. Policies with regard to blood product support, antibiotic and

anti-fungal prophylaxis, and treatment of febrile neutropenia were

determined by established local practice. BSC consisted only in the

application of these policies plus eventually the administration of

hydroxyurea in order to control white blood cell (WBC) count in case of

the proliferative disease. Patients receiving intensive chemotherapy

were systematically hospitalized for induction chemotherapy (median

hospitalization duration: 36 days) and consolidation chemotherapy

courses. Blood product transfusions were systematically administered

when hemoglobin was ≤80 g/l and platelets ≤20x109/l.

Requirements for transfusions were the same for patients treated with

lower intensity therapies (LD-AraC or hypomethylating agents) while

platelets were only transfused to patients with bleedings in the case

of treatment by BSC alone. Hospitalization was reserved for patients

with infectious complications or other severe complications for

patients belonging to two last groups of treatment.

Endpoints:

CR was defined by bone marrow aspiration, which was required to consist

of more than 50% normal cellularity with evidence of trilineage

maturation and less than 5% bone marrow blasts, no evidence of

extramedullary disease, and regeneration of the peripheral neutrophil

count to 1.0x109/l and the platelet count to 100x109/l.

The persistence of myelodysplastic features did not exclude the

diagnosis of CR. Response to therapy was evaluated after one or two

courses for patients treated with intensive chemotherapy, and after 4

to 6 courses for those treated by lower-intensity treatments. Overall

survival (OS) was the primary endpoint. It defines the time from

starting treatment to death from any cause. For remitters, disease-free

survival (DFS) is the time from CR to first event (recurrence or death

in CR).

Statistical analyses:

Surviving patients were censored at the end of September 2014 when

follow-up was up to date for 95% of patients. Descriptive statistics

was used to characterize patients and their disease. Categorical

variables were compared between treatment options by Fischer exact

tests. Continuous variables were analyzed by parametric tests (t tests)

or nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon) as appropriate. Estimated

probabilities of survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier

method, and the log-rank test evaluated differences between survival

distributions. All variables tested by univariate analyzes were

included in the multivariate analysis. Multivariate analyzes used the

Cox proportional hazard method for survival. Hazard ratios (HRs) with

95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the main endpoint.

An HR <1 indicated a benefit for one factor over another. All P

values are two-tailed, with a P value ≤0.05 considered statistically

significant. Computations were performed using BMDP PC-90 statistical

program (BMDP Statistical Software, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Results

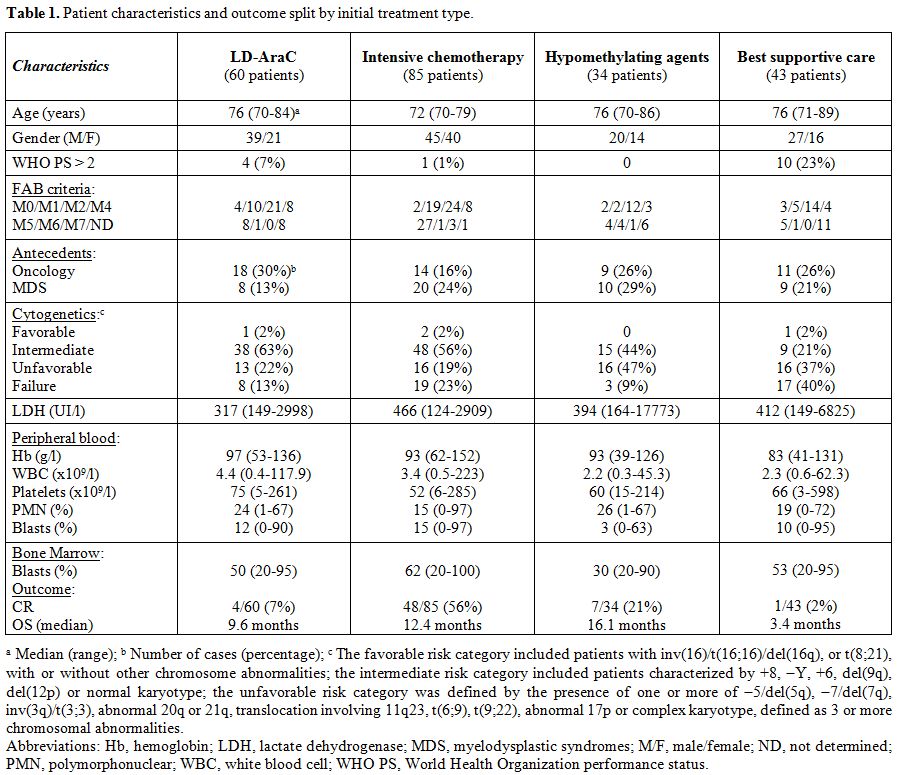

Between 2000 and 2014, 60 patients (aged 70 years or older) with newly diagnosed AML, including 35 de novo AML and 25 secondary AML, were treated in our Institution by LD-AraC. Characteristics and outcome of these patients were compared to those of patients treated during the same period of time by intensive chemotherapy (85 patients), hypomethylating agents (34 patients), or only BSC (43 patients). The characteristics of patients, split by the treatment type at onset, are provided in Table 1, which shows, as expected, differences according to the distinct therapeutic approaches.

|

Table 1. Patient characteristics and outcome split by initial treatment type. |

The median number of treatment courses given was 5 for

LD-AraC (range: 1 – 20+) with a median length of treatment of 5.1

months (range: 0.9 – 28+ months). The overall CR rate of patients

treated with LD-AraC was 7% (4 of the 60 patients). The median number

of courses to achieve CR was 4 (range, 3-9 courses). The CR rate was

significantly better in patients treated by intensive chemotherapy

(48/85 patients; 56%) (P<0.0001) and in patients treated by

hypomethylating agents (7/34 patients; 21%) (P=0.09). Median OS of

patients treated with LD-AraC was 9.6 months (95% CI, 5.8-13.5 months)

with 3-year OS of 12%.

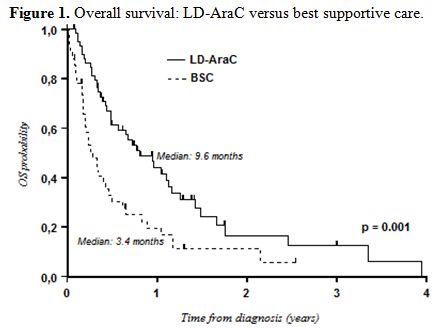

Survival with LD-AraC was better than that with BSC only (median OS: 9.6 months vs. 3.4 months; P=0.001) (Figure 1).

Although not statistically significant, intensive chemotherapy tended

to be better than LD-AraC in terms of OS (median OS: 12.4 months vs. 9.6 months; 3-year OS: 27% vs. 12%; P=0.07) (Figure 2).

However, differences in favor of intensive chemotherapy were only

confirmed for patients aged less than 75 years (median: 12.7 months vs. 9.2 months; 3-year OS: 28% vs. 10%). In patients aged ≥ 75 years, median OS was better with LD-AraC (9.6 months vs.

2.8 months). Although there was a trend for better results with

hypomethylating agents, no significant differences were observed when

compared with LD-AraC (median OS: 16.1 months with hypomethylating

agents vs. 9.6 months with LD-AraC; 3-year OS: 22% vs.

12%; P=0.1) (Figure 3). In a multivariate analysis including

cytogenetics (unfavorable vs. intermediate/favorable risk), age (<75

years vs. ≥75

years), de novo or secondary AML, and the type of treatment, only

cytogenetics was of prognostic value (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.50-2.47; P

<0.001).

|

Figure 1. Overall survival: LD-AraC versus best supportive care. |

| Figure 2. Overall survival: LD-AraC versus intensive chemotherapy. |

| Figure 3. Overall survival: LD-AraC versus hypomethylating agents. |

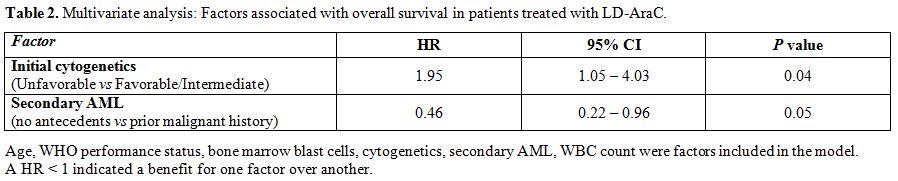

There was no clear evidence that a beneficial effect of LD-AraC was restricted to any particular subtype of patients. In the univariate analysis, similar treatment effects were observed for all ages (<75 years vs ≥75 years) (median OS: 9.2 months vs 9.6 months; P=0.92), WHO PS (0-2 vs >2) (median OS: 9.6 months vs 9.2 months; P=0.63), bone marrow blastic infiltration at diagnosis (≤ 30% vs > 30%) (median OS: 17.7 months vs 9.2 months; P=0.15), initial WBC count (≤ 10x109/l vs > 10x109/l) (median OS: 11.5 months vs 4.7 months; P=0.35), and secondary AML (prior history of MDS or cancer vs no antecedents) (median OS: 5.8 months vs 13.5 months; P=0.08). There was only a significant difference regarding initial cytogenetics (favorable and intermediate-risk vs unfavorable-risk) (median OS: 11.4 months vs 4.3 months; P=0.03). In the multivariate analysis in a model taking into account all these factors, only initial cytogenetics and secondary AML appeared of prognostic value (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Multivariate analysis: Factors associated with overall survival in patients treated with LD-AraC. |

Of the patients who received LD-AraC, 24 patients were

treated inside clinical trials, while 36 patients were not. There were

no substantial differences between those patients with respect to blood

product support, hospitalization, and days on antibiotics. However, the

clinical trials required significantly more day care visits for

patients. Median OS was 13.2 months (95% CI, 8.6-15.1 months) for

patients included in clinical trials vs 7.8 months (95% CI, 4.3-11.5

months) for those not included, with 3-year OS of 18% and 9%,

respectively (P=0.21) (Figure 4).

There were no significant differences in terms of survival between

patients receiving LD-AraC at 20 mg per day and those receiving 20 mg

twice a day.

Most of the patients (92%) upon failure after LD-AraC

therapy received only BSC with eventually a combination of

6-mercaptopurine with oral methotrexate. Five patients received a

second line therapy: one with azacitidine and 4 with a new drug inside

a phase 1 investigational trial.

| Figure 4. Overall survival: LD-AraC: Comparison between patients included into clinical trials and those not included into clinical trials. |

Discussion

Overall, despite a trend in favor of intensive chemotherapy and

hypomethylating agents over LD-AraC, no real significant advantage

could be demonstrated in terms of OS, while LD-AraC showed a

significant advantage comparatively to BSC. CR rates were higher with

intensive chemotherapy or treatment by hypomethylating agents than with

LD-AraC, but this did not translate into a significant benefit in terms

of OS. The old principle of achieving a CR with intensive chemotherapy

to convey a favorable outcome might not apply to this patient

population, for which OS and quality of life represent the most

relevant endpoints. However, one recent study regarding the quality of

life beyond 6 months after diagnosis in this patient population showed

that achievement of CR is associated with improvements in global

health, physical function, and role function without negatively

affecting other health domains.[21] In our series,

the prolonged OS contrasting with the low CR rate after treatment by

LD-AraC could be explained by the pursuit of treatment as long as the

disease was controlled and that the treatment was considered beneficial

for the patient and the selection of patients with the orientation of

frailer patients directly to BSC alone. This approach explained the

higher median number of treatment courses given in our study

comparatively to the median number of courses given in previous

studies.[15,19,22]

The same therapeutic behavior applied to hypomethylating agents can

also explain the differences between our findings and the recently

published studies of decitabine and azacitidine in elderly AML

patients.[15,19]

Our results with LD-AraC showed lower CR rates but a median OS better than those observed in previous studies.[4,12,23]

Differences in terms of CR rates could be explained by the different

schedules used. The response to LD-AraC appears dose dependent. Burnett

et al., who reported 18% to 21% of CR rate, used AraC at 20 mg twice

daily for 10 consecutive days,[12,22] while Rodriguez and Tilly, who observed 28%[2] to 32%[4]

of CR, used LD-AraC for a longer period of time (cycles of 21 days).

Theoretically, patients who achieved CR have a better median survival

compared with those who did not achieve CR. However, higher doses or

longer duration schedules are associated with a longer period of

hypoplasia. Actually our better results in terms of median OS could be

explained by a higher rate of severe toxicity in schedules with higher

doses and longer treatment[4,23] and also by recent improvements in terms of supportive care.[20]

Supportive care improvements over the last decade were also evidenced

by the difference in outcome between our series and that published by

the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center few years ago regarding patients

aged ≥70 years receiving intensive chemotherapy.[24]

They reported about patients treated between 1990 and 2008 and found

45% of CR and a median OS of only 4.6 months. This datum is close to

the results we previously reported during the same period of time,[20]

while our current series of patients treated with intensive

chemotherapy showed a significant improvement in higher CR rates and

longer survival, in relationship with improvements in supportive care.

An important point from our study was a tendency for better OS in

patients treated inside clinical trials comparatively to those who were

not. This datum stresses one more time on the importance of a regular

follow-up and on supportive care in this patient population, and can

explain the better survival with LD-AraC in our series as compared to

previous ones.[4,12,23]

The

strength of our study is that this is a report of treatment with

LD-AraC involving only elderly AML patients aged ≥ 70 years and,

therefore, reporting on a relatively homogeneous cohort of patients.

Our study, however, suffers from limitations. As expected, patient

characteristics varied significantly among the four groups of

treatment. Given the nature of clinical practice, it is conceivable

that relatively fit patients were treated with intensive chemotherapy

while less fit were offered LD-AraC or hypomethylating agents, and

frail patients received only BSC. Other limitations mainly concerned

the retrospective profile of the study with unbalanced distribution of

the treatment options, the small size of the cohorts, the absence of

data regarding comorbidities (such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or

cardiac pathology), absence of any quality of life questionnaire, and

the under-representation of patients who received intensive

chemotherapy during the last period of study while the hypomethylation

cohort belongs mainly to this same recent period. The main goal of our

study was to report the results of LD-AraC therapy in the real life of

one hematology center. In this setting, comparisons among treatments

used in this patient population were authorized, although involving

unbalanced groups.

Although a benefit in OS has been demonstrated

with LD-AraC compared with BSC, outcome with LD-AraC remains

unsatisfactory. A true step forward in the treatment of AML in elderly

patients can be expected from the development of more effective

therapies and the further improvement of supportive measures. Recently,

a lower-intensity, prolonged-therapy program testing clofarabine and

LD-AraC alternating with decitabine was well tolerated and highly

effective in older patients with AML.[25] Hypomethylating agents also represent a promising alternative to intensive chemotherapy in this patient population.[15,19]

On the basis of our findings, LD-AraC did not show sufficient evidence

of benefit over hypomethylating agents to be considered again as the

standard treatment for this patient population, but can still represent

a baseline against which new promising agents may be compared either

alone or in combination.[22]

Author contributions

MH interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; ME collected the data and provided technical support; IT was responsible for coordinating cytogenetics; AP was responsible for coordinating morphological data; FB, HL, SD, MM, FN, CP, and EW included patients; GS gave final approval; XT included patients, collected the data, conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

[TOP]