Received: January 17, 2016

Accepted: February 8, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016017, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.017

This article is available on PDF format at:

Marco Cerrano1, Elena Crisà1, Valentina Giai1, Mario Boccadoro1 and Dario Ferrero1

1 Hematology Division, Università degli Studi di Torino, Turin, Italy.

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Anemia in the elderly is a common but

challenging clinical scenario. Here we describe the case of an older

woman who presented with anemia and elevated inflammation markers.

After a complete diagnostic work-up, a definite etiology of the anemia

could not be found so eventually a bone marrow biopsy was performed and

she was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome. She responded well to

erythropoietin treatment but her inflammation markers remained elevated

thus a positron emission tomography was performed. It turned out that

the patient suffered from giant cell artheritis and her anemia

completely resolved after steroid treatment. Our case outlines that it

is necessary to pay particular attention to anemia of inflammation,

which could be due to several and often masked conditions.

Myelodysplatic syndromes should be considered when other causes have

been ruled out, but their diagnosis can be difficult and requires

expertise in the field. |

Introduction

Anemia in the elderly is a very common condition that contributes to morbidity and mortality and significantly impairs quality of life. In the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) study the incidence of anemia in men and women older than 65 was 11% and 10.2%, respectively,[1] thus representing a problem almost every physician deals with. Several causes often contribute to anemia in this age group, and it is not always possible to find a unifying diagnosis,[2] hence it frequently represents a challenging clinical scenario. Here we present the case of an elderly Italian woman investigated for persistent anemia and elevated inflammation markers.

Case Report

Case presentation:

A 68 year old woman was admitted to a primary care center for worsening

asthenia and fatigability. During the two months before admission, she

also referred weight loss, mild fever, and cough.

Clinical

history: She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer 13 years before, and she

was treated with surgery and a carboplatin-containing chemotherapy

regimen. No signs of disease recurrence were found afterwards. She

suffered from hypertension, well controlled with medical therapy,

arthrosis, and chronic constipation.

Initial work-up:

At admission clinical examination was unremarkable. Blood count showed

severe normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 7.5 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume

90 fL) and mild thrombocytosis (platelets 452000/µL) while reticulocyte

count, leucocyte count, and differential were normal. Iron or vitamin

deficiencies were ruled out, and lactate dehydrogenase, serum

creatinine, thyroid functioning and liver tests were normal. Reactive C

protein (RCP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum ferritin,

however, were significantly increased (18.2 mg/dL, 160 mm/h and 1136

ng/mL, respectively).

Differential diagnosis: Nutritional

deficiencies (i.e. lack of iron, vitamin B12 or folic acid), chronic

kidney disease, thalassemia trait and inflammation are the most

frequent causes of anemia in elderly patients and should be considered

first.[3] Hemolysis, radio- and chemo-therapeutic interventions,

hypothyroidism or hepatic insufficiency are other common causes that

should be ruled out. Anemia due to inflammation (AI) is maybe the most

complex one. As a matter of fact, several pathophysiological mechanisms

are involved such as disturbance of iron homeostasis, impaired

proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells and reduced erythropoietin

response. Furthermore, the causes of inflammation are often multiple

and not always the source is apparent (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease,

rheumatologic disorders, cancer, infections).[4]

Besides, AI

can mask iron deficiency because, in the presence of both these

conditions, the commonly used serum iron-status indicators (namely

iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation and ferritin) can be

difficult to interpret.[3] The discovery of hepcidin, the main

regulator of iron homeostasis, significantly improved our understanding

of the pathophysiology of AI and the measurement of serum hepcidin

level, which is down-regulated in case of iron deficiency and

up-regulated in presence of inflammation, soon could become a useful

tool in the diagnostic work-up of anemia in the elderly.[5]

Further examinations:

Since inflammation markers remained elevated in our patient, other

investigations were performed to rule out an infection, an autoimmune

disease or malignancy: microbiological tests were negative,

autoimmunity tests showed a low antinuclear antibody titer and a weak

rheumatoid factor positivity, chest, and abdomen computed tomography

and echocardiography were normal. Anemia persisted, no precise

inflammatory source could be found and a bone marrow (BM) trephine

biopsy was eventually performed and evaluated by the local pathologist.

It showed a hypercelullar bone marrow with trilinear dysplasia,

abnormal localization of immature precursors and 1.5% of blasts. She

was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)-unspecified, without

blast excess, likely secondary to chemotherapy exposure. Cytogenetic

analysis and BM aspiration were not performed.

Differential diagnosis:

A BM dysfunction, either primary, such as MDS, or secondary to

neoplastic or infectious agents, should be considered after ruling out

all other causes of anemia. MDS are suspected in elderly patients in

case of unexplained cytopenia, more commonly isolated macrocytic

anemia, and confirmed with a BM aspirate and biopsy.

Hematologic follow-up:

The patient was then discharged and referred to our center. When she

presented to our clinic, she was afebrile, reported fatigue and

weakness. Her blood count was stable with isolated anemia requiring

weekly transfusions and ESR and RCP remained elevated. In order to

confirm the diagnosis, we proposed her a new BM evaluation with

morphological and cytogenetic analysis but the patient refused it. As

per our policy, we tested the blood level of Wilms tumor gene

transcript (frequently elevated in acute myeloid leukemia and MDS),[6]

and it was in the normal range. Giving the diagnosis of low risk MDS

with isolated anemia, we checked serum erythropoietin level, that

resulted in the reference range but inadequate for the degree of anemia

(31.7 mUI/mL), therefore we started the patient on recombinant

erythropoietin, 40000 U weekly. Her anemia progressively improved and

she achieved an erythroid response[7] after 3 weeks of treatment,

becoming transfusion independent.

Final diagnosis:

So far it could have looked like a typical low-risk MDS responsive to

erythropoietin. However, the patient was still complaining of

arthralgias and ESR and RCP remained elevated. Moreover, she reported

the appearance of a livedo reticularis on her lower limbs. To better

clarify the case, given the persistently elevated inflammation markers

and the personal history of ovarian cancer, a total body positron

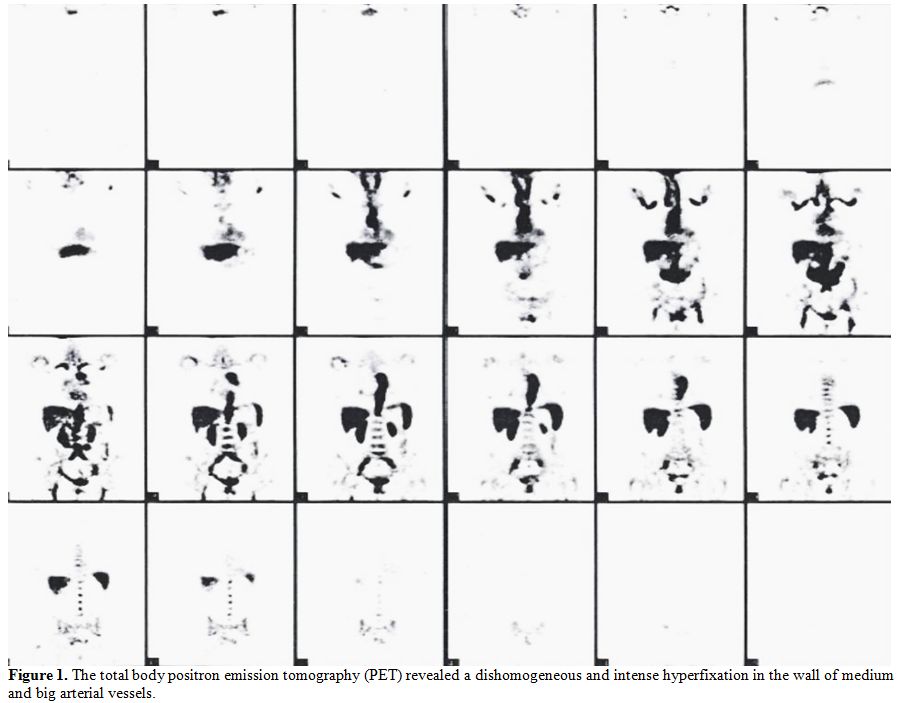

emission tomography (PET) was performed. Surprisingly, it revealed a

dishomogeneous and intense hyperfixation in the wall of medium and big

arterial vessels, consistent with a vascular inflammatory process (Figure 1).

We referred the patient to a rheumatologist, and she underwent a biopsy

of the temporal artery which revealed histology consistent with giant

cell arteritis (GCA). Erythropoietin was discontinued; she was started

on corticosteroid therapy and her anemia rapidly resolved. Seven years

after GCA diagnosis our patient is doing well, with normal blood counts

and without any further therapy.

|

Figure 1. The total body positron emission tomography (PET) revealed a dishomogeneous and intense hyperfixation in the wall of medium and big arterial vessels. |

Discussion

In the case we are presenting, the initial work-up of our patient

demonstrated severe anemia associated with significantly elevated

inflammation markers, prompting the diagnosis of AI. However, even

though several examinations were performed, a clear etiology could not

be found and eventually the patient underwent a BM biopsy. The

diagnosis seemed to be MDS.

MDS usually present with anemia,

isolated or combined with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia,[8] but

anemia and thrombocytosis can seldom occur.[9,10] Anemia is usually

macrocytic (rarely it can be normocytic or even microcytic),[11]

reticulocyte count is (relatively) reduced, there can be signs of

dyserithropoiesis and serum ferritin level can be elevated. On

peripheral blood smear a dimorphic red-cell population that includes

oval macrocytes can be seen, often together with neutrophils or

platelets abnormalities (e.g. hypogranulated neutrophils or pseudo

Pelger–Huët cells).[8] MDS diagnosis is confirmed by performing a BM

examination. It is important to carry out both BM aspirate and trephine

biopsy as the first one is essential to evaluate cellular morphology

and to count the proportion of blasts while the latter allows for

determination of BM cellularity and architecture.[12] Indeed the

pathological hallmark of MDS is BM dysplasia that can only be assessed

by morphology, which represents the most important tool to establish a

definite diagnosis.[13] The 2008 World Health Organization

classification of MDS requires the demonstration of unequivocal

dysplasia in at least 10% of the cells of the erythroid, granulocytic

or megakaryocytic lineage.[14] However, nutritional deficiencies,

medications, toxins, growth factor therapy, inflammation or infections

can sometimes cause secondary dysplasia and thus they should be

excluded before a diagnosis of MDS is established. In the cases of MDS

with an excess of blasts or with more than 15% of ring sideroblasts in

the erythroid precursors the diagnosis is usually straightforward. In

the other cases, the morphologic evidence of dysplasia may not be

unequivocal, and the presence of a specific cytogenetic abnormality or

the immunophenotyping can be helpful in confirming the

diagnosis.[14,15] If unilinear dysplasia is the only proven sign of

myelodysplasia an observation period of 6 months and a second BM

investigation is recommended to establish a definite MDS diagnosis.[14]

The complexity of diagnosis of MDS can lead to mistakes and significant

discrepancies between peripheral and tertiary care centers have been

outlined.[16,17] Therefore, it appears important that an experienced

hematologist along with an hemopatologist establish the diagnosis of

MDS and a discussion with other colleagues experts in this field could

be useful when in doubt.

Our patient was eventually diagnosed with

GCA. GCA can present with typical symptoms such as a headache, jaw and

tongue claudication, scalp tenderness, visual disturbance and

manifestations of polymyalgia rheumatica[18] and the diagnosis still

relies on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification

criteria [3 of the following 5 criteria are required: 1) age 50 years

or older, 2) new-onset localized headache, 3) temporal artery

tenderness or decreased temporal artery pulse, 4) ESR of at least 50

mm/h, 5) abnormal artery biopsy specimen characterized by mononuclear

infiltration or granulomatous inflammation].[19] However, the diagnosis

of GCA can be difficult due to the variability of clinical

presentation, and the utility of these criteria in clinical practice

has been questioned.[20] Furthermore, the presentation of GCA can be

atypical and cases showing only anemia and raised inflammatory markers

have been reported.[21] A persistent dry cough can be a presenting

symptom too, either isolated or associated with typical

manifestations.[22] Our case was challenging because the patient

complained only of anemia related symptoms, arthralgias, and mild fever

and the elevated inflammation markers could not be easily interpreted.

It outlines that is it is necessary to be aware of the entire spectrum

of symptoms of GCA in order to consider it in the differential

diagnosis of anemia. Indeed, our patient initially complained of a

cough, but this symptom was not reported later. The use of PET can

certainly facilitate the diagnosis of GCA, but it is expensive, and it

exposes patients to a significant radiation risk.

An association

between autoimmune diseases, including vasculitis, and MDS has been

reported, especially in case of chronic myelo-monocytic leukemia and

high risk MDS.[23-25] However, in our patient anemia completely

resolved with steroid treatment and she is currently doing well seven

years after GCA diagnosis without any further therapy.

Conclusion

Authorship and Disclosures

MC reviewed the literature and wrote the paper. DF followed the patient and wrote the paper. EC and VG reviewed the paper. MB supervised the work and provided founds.

References

[TOP]