Received: February 15, 2016

Accepted: March 23, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016023, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.023

This article is available on PDF format at:

Marcus Kühn, Kety Sammartin, Mitja Nabergoj and Fabrizio Vianello

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Peripheral neuropathy is a common

complication of arsenic toxicity. Symptoms are usually mild and

reversible following discontinuation of treatment. A more severe

chronic sensorimotor polyneuropathy characterized by distal axonal-loss

neuropathy can be seen in chronic arsenic exposure. The clinical course

of arsenic neurotoxicity in patients with coexistence of thiamine

deficiency is only anecdotally known but this association may

potentially lead to severe consequences. We describe a case of acute irreversible axonal neuropathy in a patient with hidden thiamine deficiency who was treated with a short course of arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Thiamine replacement therapy and arsenic trioxide discontinuation were not followed by neurological recovery and severe polyneuropathy persisted at 12-month follow-up. Thiamine plasma levels should be measured in patients who are candidate to arsenic trioxide therapy. Prophylactic administration of vitamin B1 may be advisable. The appearance of polyneuropathy signs early during the administration of arsenic trioxide should prompt electrodiagnostic testing to rule out a pattern of axonal neuropathy which would need immediate discontinuation of arsenic trioxide. |

Case Report

Although polyneuropathy is common following arsenic trioxide therapy

of subjects with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), symptoms are

generally mild and they disappear after completion of arsenic

treatment. In November 2014, a 72-year old Caucasian woman was admitted

to this Unit with fever and pancytopenia (white blood cell count 0.19x109/L, hemoglobin 76 g/L, platelets 41x109/L).

She had a medical history of lobular carcinoma of the left breast

treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy in 2012, Hashimoto

thyroiditis, arterial hypertension. There was no prior neurological

disorder and physical examination was unremarkable. Coagulation tests

showed reduced prothrombin time ratio (59%) and normal activated

partial thromboplastin time, a slightly reduced fibrinogen (1,4 g/L)

and increased D-dimer (8634 µg/L). Bone marrow evaluation was

consistent with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) according to

French-American-British (FAB) classification system. The patient was

started on all-trans retinoic acid (45 mg/m2)

according to protocol APL0406[1] and, by day 3, arsenic trioxide (ATO)

10 mg/d was added at the time of PML/RAR alpha rearrangement

identification by PCR. The clinical course was complicated by

differentiation syndrome, which manifested as mild increase of

creatinine levels, peripheral edema and pleuro-pericardial effusion.

All-trans retinoic acid was therefore stopped on day 12, dexamethasone

and furosemide added and the patient was continued on arsenic trioxide.

On

day 16, the patient gradually regained kidney function and all-trans

retinoic was resumed. Starting on day 22, progressive cognitive

impairment, insomnia, slurred speech, spatial and temporal

disorientation occurred. As this worsening clinical picture was

concomitant to hypernatremia (up to 160 mmol/L, reference values

136-145 mmol/L), neurological symptoms were attributed to

sodium-related hyperosmolarity.

Over the following days an

impaired level of consciousness and lethargy was noticed. Progressive

and appropriate normalization of natriemia did not improve neurological

dysfunction.

Additional diagnostic procedures were performed. A

CT scan of the brain did not reveal abnormalities related to the acute

clinical picture, showing only age-related mild cerebral and cerebellar

atrophy. Cerebrospinal fluid showed only mild protein

elevation.

Plasma

levels of vitamin B1 were low (22 nmol/L, reference values 66-200

nmol/L) and supplementation was started. Over the following 5 days the

patient showed a slow but progressive full recovery of cognitive

functions.

Unexpectedly, at normalization of cognitive function,

a pattern of symmetric peripheral neuropathy involving upper and lower

limbs became clinically evident. Physical examination showed that left

and right hands were severely weak, particularly the abductor pollicis

brevis, with mild strength reduction in the proximal arms. Deep-tendon

reflexes were absent. There was bilateral foot drop, and the patient

was unable to walk. Strength in the ankle dorsiflexors, extensor

hallucis longus, extensor digitorum brevis, and toe flexors was

severely compromised. There was no muscle atrophy or fasciculation, and

the remainder of the neurologic examination was normal.

Electromyography (EMG) showed a severe sensory-motor axonal neuropathy

of the upper and lower extremities with a greater reduction of sensory

action potential.

Meanwhile on day 28 arsenic trioxide had been

stopped according to the therapy protocol. Bone marrow evaluation

showed molecular remission. At that time the patient was bedridden

because of a severe neurological impairment, so we chose not to

administer consolidation therapy as it would have been required

according to standard protocol.[1] The patient was then continued on

maintenance therapy with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine. Molecular

remission was confirmed in bone marrow aspirate at the 13-month

follow-up.

Over the following on 6 months from arsenic trioxide

discontinuation, the patient regained full proximal muscle strength but

with almost complete persistence of marked distal weakness of the

hands, ly finger and wrist extensors, weakness of foot dorsiflexors

bilaterally and the inability to maintain an upright position.

Neurological examination and EMG were substantially unchanged at the

12-month follow-up evaluation.

We believe that occult thiamine

deficiency exacerbated arsenic trioxide neurotoxicity causing an

unexpected and irreversible distal axonal symmetric neuropathy. This is

the first report of acute and irreversible axonal neuropathy in a

patient treated with arsenic trioxide with a background of thiamine

deficiency. Peripheral neuropathy has long since been associated with

the use of arsenic. Several clinical studies have been published on ATO

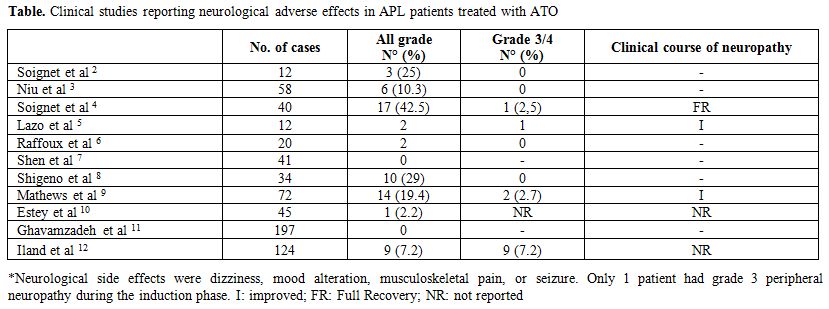

treatment of patients with APL (Table).[2-12]

Although details on grade and duration of peripheral neuropathy were

not always clearly included, overall grade 3/4 neuropathy accounts for

about 0.5% of patients treated with ATO and recovery is always

observed. Yip et al reported a case of severe neurotoxicity during

arsenic therapy in a subject with APL and occult thiamine

deficiency.[13] However, thiamine administration led to rapid

improvement suggesting a major role of thiamine deficiency over arsenic

toxicity.

Severe and irreversible arsenic neurotoxicity in the

setting of thiamine deficiency can be explained by their common

metabolic target. In fact, thiamine deficiency and arsenic exposure

severely impair pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity, an enzyme

responsible for converting glucose to energy in high yield. As neural

tissues are highly dependent on carbohydrates for energy production and

cellular metabolism, it is tempting to speculate a synergic detrimental

neuropathic effect leading to the severe toxicity observed in our

patient. Of interest, we found electrophysiological findings consistent

with acute axonal dysfunction without pattern of demyelination. This

type of damage is the classic electrophysiological and

histopathological finding in beriberi neuropathy whereas arsenic axonal

toxicity characteristically coexists with segmental

demyelination.[14,15] An acute pattern of axonal damage has been

reported as a manifestation of arsenic poisoning but it has not been

observed as a side effect of short term administration of arsenic

trioxide at therapeutic dosage.[16] Thus, arsenic trioxide therapy may

lead to axonal loss through the exacerbation of the metabolic damage to

the nerve tissue induced by thiamine deficiency. This may have

relevance in considering prophylactic administration of thiamine to

subjects undergoing arsenic trioxide therapy for APL, a clinical

approach already adopted by others[7] and supported by animal models of

antioxidant properties of thiamine in arsenic treated animals.[17]

In

conclusion, occult thiamine deficiency may contribute to arsenic

toxicity and the combination may cause irreversible axonal neuropathy

which must be considered when monitoring APL patients on arsenic

trioxide therapy. Prophylactic administration of thiamine may be

considered in this setting.

|

Figure 1. Clinical studies reporting neurological adverse effects in APL patients treated with ATO |

References

[TOP]