Received: February 3, 2016

Accepted: May 15, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016027, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.027

This article is available on PDF format at:

Federica Sorà, Patrizia Chiusolo, Luca Laurenti, Francesco Autore, Sabrina Giammarco and Simona Sica

Istituto di Ematologia, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Roma, Roma.

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Life-threatening bleeding is a major

and early complication of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), but in

the last years there is a growing evidence of thromboses in APL. We

report the first case of a young woman with dyspnea as the first

symptom of APL due to massive pulmonary embolism (PE) successfully

treated with thrombolysis for PE and heparin. APL has been processed

with a combination of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic

trioxide (ATO) obtaining complete remission. |

Case Report

Bleeding is the usual manifestation of acute promyelocytic leukemia

(APL) related coagulopathy and is associated with significant morbidity

and mortality.[1-3] Thrombocytopenia,

hyperfibrinolysis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) are

the leading causes of bleeding at diagnosis and shortly after the

introduction of treatment.[4] On the contrary

thrombotic complications were considered rare before the introduction

of ATRA. As a result, while the APL-related bleeding diathesis has been

investigated extensively and the pathogenesis has been elucidated to a

greater extent, the importance of thrombosis in APL, as a cause of

morbidity and mortality, has been undervalued and scarcely studied. So,

the exact pathogenetic mechanism of thrombosis in APL is still a matter

of controversy, even if the incidence of thrombotic complications in

APL seems to be rising. This could simply be due to higher levels of

vigilance and availability of advanced diagnostic modalities, or, due

to the increasing use of ATRA as suggested by Rashidi et al in a very

exhaustive review of this

topic.[5-7] There are

several potential explanations for thromboembolic complications in APL,

including: (i) A mere coincidence (e.g. genetic predisposition,

prolonged bed rest or immobility). (ii) Thrombogenicity of APL cells.

(iii) The use of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). (iv) The combination

of ATRA and antifibrinolytic agents, and the differentiation syndrome

caused by ATRA (i.e. ATRA syndrome).[4] We here

present the case of a young patient admitted to our hospital with a

massive pulmonary embolism as the first sign of acute promyelocytic

leukemia requiring thrombolysis and heparin. Finally, this case offers

a snapshot of the kinetic of APL related coagulopathy on therapeutic

heparin during ATRA and ATO and suggests the role of ATO and ATRA in

the treatment of APL patients with major thrombosis at diagnosis.

Methods and Result

A 24-year-old Caucasian female was admitted to the emergency

department of a peripheral hospital because of a few days history of

progressive shortness of breath. She also experienced an increasing

asthenia, uncommon for a young girl. Physical examination showed pallor

in the absence of bleeding, lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. She

was afebrile and had only mild fluid retention. Vital signs including

blood pressure and heart rate were normal. Respiratory rate was 20

breaths per minute and O2 saturation by pulse oximetry was 96% with a FiO2

0.35 support by face mask. Her blood test revealed normocytic

normochromic anemia (Hb 7.7 g/dl) severe leucopenia and neutropenia

(WBC 800/mm3, ANC 480) with a platelet count of 109,000/mm3.

Peripheral smear did not show abnormal cells. Biochemistry values and

coagulation profile were normal. Chest X-Ray revealed ground-glass

opacity in right upper lobe.

The patient was referred 48 hours

later to our Division of Hematology. Sh complained of shortness of

breath requiring oxygen supplementation and she had two episodes of

hemoptysis. Her past medical history was unremarkable except for

adrenogenital syndrome requiring long-standing estroprogestinic support

and coeliac disease. She denied medication allergies, use of alcohol,

cigarettes or illicit substances. Neutropenia and anemia with a

platelet count of 110,000/mm3 were

confirmed and coagulation profile was normal except for d-dimer 7283

ng/ml (normal values <300ng/ml). International Society on Thrombosis

and Hemostasis (ISTH) DIC score was 4.[8]

Bone

marrow aspiration was carried out showing a massive infiltration of

pathologic promyelocytes and faggot cells consistent with APL. These

cells were markedly positive to myeloperoxidase. Flow cytometry

demonstrated an extensive positivity for CD117, myeloperoxidase (MPO),

CD45, CD13, CD33, and partial for CD34 and absence of HLA-DR, CD2

expression. CD15 was not tested. Fluorescence in situ hybridization

(FISH) revealed that 94% of nuclei were positive for t(15;17).

Cytogenetics showed a normal karyotype 46XX (20 cells). PML/RAR alpha

chimeric protein, bcr3 type, was detected by reverse

transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from leukemic blasts.

FLT3 was positive.

Computerized tomography of the chest revealed a

massive acute pulmonary embolism with large filling defects of both

main arteries also involving lobar, segmental and subsegmental

arteries. There were also peripheral wedge-shaped areas of

hyperattenuation representing infarcts in many different lobes and a

minimal pericardial effusion was detected. The patient was started

immediately on intravenous sodium heparin and ATRA (45mg/m2 per day in two divided doses orally) with prophylactic methylprednisolone (0.5mg/kg) to prevent the differentiation syndrome.[10]

However, few hours later her general condition deteriorated with

hypotension, tachypnea (respiratory rate 32 breaths per minute) and

hypoxia with an oxygen saturation of 80% requiring a progressive

increase of FiO2 up to 1. Arterial blood gasses showed pH 7.477, pCO2 of 23.3 mm Hg, and pO2 of 59 mm Hg. Alteplase was given at the dose of 100 mg over two hours according to the recent guidelines from AACP.[9]

Sodium heparin was titrated in order to obtain 1.5 times the baseline

control value of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Bedside echocardiogram demonstrated mild right ventricular (RV)

hypertrophy with normal global kinesis. Pulmonary artery pressure

(PAPS) was estimated to be 31 mmHg. Lower limbs venous color Doppler

ultrasonography did not reveal signs of deep or superficial thrombosis.

Inherited and acquired thrombophilia screening tests were negative.

After thrombolysis, her pulmonary function dramatically improved.

At the second day of ATRA, considering the diagnosis of low-risk APL[10] and the requirement of long-term anticoagulation, arsenic trioxide (ATO) at the standard dose of 0.15mg/Kg/die was added.[11]

At the third day, breath rate was normal and oxygen supplementation was

discontinued. On day +11 of ATO+ATRA she developed mild chest pain,

asthenia and a slight increase in troponin levels and a T wave

abnormality on the ECG; chest CT scan was unchanged raising the

suspicion of a differentiation syndrome. ATRA was discontinued for five

days and dexamethasone 10mg bid was given until the complete resolution

of the symptoms. Leukocytosis, defined as a white-blood-cell count

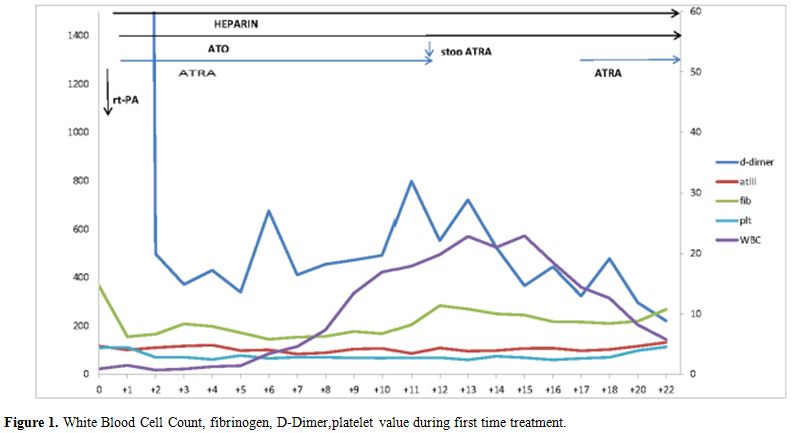

(WBC) of more than 10×109 per liter, developed at day+ 17 and was successfully managed with hydroxyurea.[11] The kinetic of coagulative parameters, including platelets and WBC count during induction with ATO and ATRA, is depicted in figure 1.

|

Figure 1. White Blood Cell Count, fibrinogen, D-Dimer,platelet value during first time treatment. |

After 50 days of ATRA and ATO peripheral blood cell count

and bone marrow biopsy documented the complete morphological and

molecular remission of APL and the patient was discharged from the

hospital on low molecular weight heparin. CT showed a slight reduction

of EP defects and the areas of hyperattenuation representing infarcts.

Echocardiogram described normal kinesis and valvular function with a

slight increased PAPS (35 mmHg). Consolidation therapy with ATRA and

ATO was delivered.[11]The patient is currently alive

and well after the end of ATO consolidation and in molecular CR at 20

months from diagnosis and off anticoagulation.

Discussion

Thrombotic events (TE) appear to be more common in acute

promyelocytic leukemia (APL) than in other acute leukemias, with

reported incidence ranging from 2 to 10-15%. Data from large

cooperative groups have been published after initial reports of

increased thrombotic events in APL when a combination of ATRA and

chemotherapy was applied.[12] The incidence of thrombosis in APL patients was 8.8% in AIDA protocol from the GIMEMA group[13-14] and 5.1% in PETHEMA LPA96 and LPA99 Protocol,[15] occurring mainly at diagnosis or during induction.[1]

In the GIMEMA study risk factors for the development of thrombosis

included higher leukocyte count, the prevalence of bcr3 transcript type

and a malignant cell phenotype including CD2 and CD15. ATRA-induced

differentiation syndrome was associated with a severe increase of

thrombotic complications in the PETHEMA group experience. These data

were partially confirmed in a recent paper from Mitrovic et al[16]

in a retrospective study of 63 APL patients. The authors reported an

incidence of thrombotic complications of 20.6%, including asymptomatic

thrombosis, and again more frequently observed during induction.

In

our case massive PE developed at diagnosis. No APL-specific risk

factors for thromboses or inherited or acquired thrombophilia were

found in this particular case except for bcr3 isoform and

estroprogestinic exposure. Despite the concurrent diagnosis of APL, the

patient required both heparin and thrombolysis for PE. Two other

attempts to treat major thromboses with thrombolysis were reported in

APL, one patient was treated for Budd-Chiari syndrome[17] and relapsed APL and a more recent one APL patient received local thrombolysis for arterial thrombosis at the onset of APL.[18] One additional patient underwent to thrombolysis for PE when in remission of APL.[19]

The combination of ATRA and ATO, adopted in considering the low-risk

APL category of our patient and the need for prolonged and sustained

anticoagulation, demonstrated to be an efficient regimen, also

significantly reducing the risk of prolonged thrombocytopenia due to

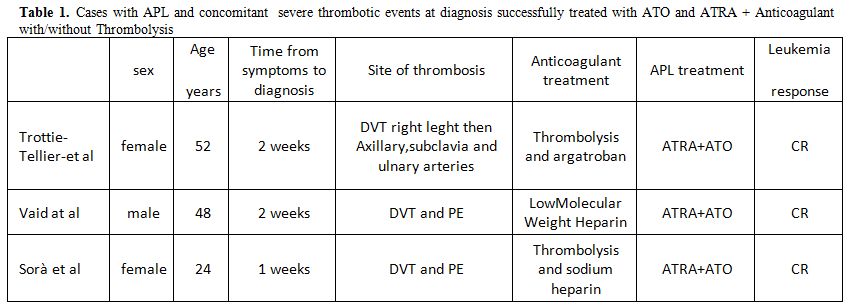

chemotherapy. Two additional cases with severe thrombotic events at

diagnosis successfully treated with anticoagulants with or without

thrombolysis when in ATO and ATRA have been published recently[18,20] and reported in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Cases with APL and concomitant severe thrombotic events at diagnosis successfully treated with ATO and ATRA + Anticoagulant with/without Thrombolysis |

Although this case is exceptional, being to the best of our

knowledge the only reported case of thrombolysis for massive PE

attempted in APL at diagnosis, it raises several points of

discussion Thrombosis should be kept in mind for observation and

treatment of APL patients as suggested by a growing body of evidence.[1]

An accurate evaluation of risks should be pursued and anticoagulation

including thrombolysis might be necessary for APL at least in

catastrophic thrombosis. Although the management with ATRA and ATO in

induction, is largely anecdotal in APL patients anticoagulated, with

thrombosis and concurrent risk of bleeding, avoiding chemotherapy might

allow adequate anticoagulation by reducing the length and the severity

of thrombocytopenia. In literature now the results of some trials[21,22]

support the not inferiority of ATRA/ATO-based regimen in “all-risk”

acute promyelocytic leukemia regarding efficacy and safety; these data

and our experience suggest this combination also in high-risk APL

patients submitted to anticoagulation.

References

[TOP]