Received: June 29, 2016

Accepted: July, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016045, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.045

This article is available on PDF format at:

Francesco Maura1, Lucia Farina1 and Paolo Corradini1,2

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the

second most common histotype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and it is

generally characterized by a heterogeneous clinical course. Despite

recent therapeutic and diagnostic improvements, a significant fraction

of FL patients still relapsed. In younger and/or fit FL relapsed

patients bone marrow transplant (BMT) has represented the main salvage

therapy for many years. Thanks to the ability of high-dose chemotherapy

to overcome the lymphoma resistance and refractoriness, autologous stem

cell transplantation (ASCT) can achieve a high complete remission rate

(CR) and favorable outcome regarding progression-free survival (PFS)

and overall survival (OS). Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

(alloSCT) combines the high dose chemotherapy effect together with the

immune reaction of the donor immune system against lymphoma, the

so-called ‘graft versus lymphoma’ (GVL) effect. Considering the

generally higher transplant-related mortality (TRM), alloSCT is mostly

indicated for FL relapsed after ASCT. During the last years, there have

been a great spread of novel effective and feasible drugs. Although

these and future novel drugs will probably change our current approach

to FL, the OS post-BMT (ASCT and alloSCT) has never been reproduced by

any novel combination. In this scenario, it is important to correctly

evaluate the disease status, the relapse risk and the comorbidity

profile of the relapsed FL patients in order to provide the best

salvage therapy and eventually transplant consolidation.

|

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common histotype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with an incidence of approximately 15.000 new cases/year in the United States.[1] The incidence increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis being 60 years. FL clinical course is generally heterogeneous with progression-free survival (PFS) ranging from 71% to 35% at 10 years, according to the Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Index Score (FLIPI),[2] and 91% to 51 % at 3-year, according to with Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Index Score-2 (FLIPI-2).[3] During the last years, the FL clinical management has been progressively improved thanks to the use of more accurate and sensible diagnostic technics such as the Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and the Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) monitoring[4-11] and the introduction of novel effective agents.[12] Anti-CD20 humanized antibody Rituximab led to one of the most important changing in FL clinical practice, and probably still represents the major improvement in FL therapy and outcome in the last 20 years.[13-15] Indeed, different studies show how the combination of rituximab and standard chemotherapy (i.e, CHOP) can significantly improve the FL prognosis and survival compared to standard chemotherapy alone. Despite all these advances, a significant proportion of FL patients still experiences an early or late relapse.

Bone marrow transplant (BMT) has been widely investigated to achieve a better response and improve the survival in FL.[16-18] Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has represented one of the main treatments for relapsed FL thanks to the ability of high-dose chemotherapy to overcome the lymphoma resistance and refractoriness. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) combines the high dose chemotherapy effect together with the immune reaction of the donor immune system against lymphoma, the so-called ‘graft versus lymphoma’ (GVL) effect. Although the BMT anti-lymphoma activity is generally superior to standard chemotherapy, this approach is limited to young and fit patients due to the transplant-related toxicity and mortality (TRM). In the last years, thanks to the novel less toxic conditioning regimens available and to the significant improvement in supportive cares, the proportion of FL patients potentially eligible to ASCT and/or alloSCT has progressively expanded. Today these procedures are feasible up till the age of 65-70 years.[16,17]

In this review we examine the current state of the

art of FL treatment, focusing in particular on the role of BMT and its

indications.

Transplant in the First Line: End of the Story?

In the pre-rituximab era, three different main trials investigated the role of intense chemotherapy with final ASCT consolidation as first-line therapy for FL patients.[19-21] Although this approach showed a significant progression-free survival (PFS) improvement, the advantage was abolished by the high incidence of therapy-related malignancies seen in the ASCT arms.[22-24] The Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) investigated the combination of rituximab with high-dose sequential (HDS) chemotherapy regimens, including ASCT as final consolidation, showing a significant improvement in terms of PFS and overall survival (OS).[25] However, the first randomized trial conducted by GITMO and Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi (IIL) failed to demonstrate any survival advantage of R-CHOP followed by ASCT compared to R-CHOP alone in high-risk FL patients.[7] Enrolling a total of 136, patients this study represents the main clinical trial that investigated the role of ASCT in the first line FL in rituximab era. After a median follow-up of 51 months, the ASCT arm showed a clear 4-year event-free survival (EFS) advantage (62% versus 28%); however, no difference was seen in OS (81% versus 80%), confirming what was previously described in trials without the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. The final results of this trial were particularly interesting considering the MRD monitoring data. A significantly higher rate of molecular remissions (MRs) was achieved in the ASCT arm compared with the conventional chemotherapy (80% versus 44%, respectively), with MRD status being the strongest predictor of outcome. Importantly, patients randomized to the non-transplant arm that achieved MRD negativity did not show any difference in outcome compared to MRD-negative patients who underwent ASCT.[7] These data suggest that MRD negativity should be considered as one of the main end points in FL therapy.

A further improvement in PFS post R-CHOP was recently obtained by the introduction of rituximab maintenance, as demonstrated by the PRIMA trial.[26] The last update showed a PFS at 6-year of 59% in maintenance vs. 42.7% of the non-maintenance arm.[27] These results demonstrate that standard immune-chemotherapy regimens may achieve a long remission in more than half FL patients. A sub-analysis of the PRIMA study also showed that PET-positive patients had a significantly inferior PFS at 42 months compared to those who became PET negative (32.9 versus 70.7%). The risk of death was also increased in PET-positive patients.[28] In this perspective, the introduction of the PET scan into the clinical practice may further improve the disease response evaluation, because it may be able to detect patients with refractory disease or with an early complete remission.[5,9-11,29] An ongoing prospective trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL) group is evaluating whether the disease assessment by combination of MRD monitoring and PET scan after rituximab-based induction therapy can identify FL patients who need an intensification or, conversely, those that may avoid rituximab maintenance therapy (EUDRACT NUMBER: 2012-003170-60).

Finally, the incorporation of novel agents such as bendamustine and lenalidomide in the first line treatment showed promising results that may produce further potential improvement in term of efficacy and toxicity among all FL.[30-34]

In conclusion, considering the absence of survival

benefit of ASCT consolidation and the continuous improvements in

non-transplant approaches, ASCT should be avoided in the first line

therapy for FL patients.

Relapsed Follicular Lymphoma Patients: New Drugs vs. High Dose Chemotherapy

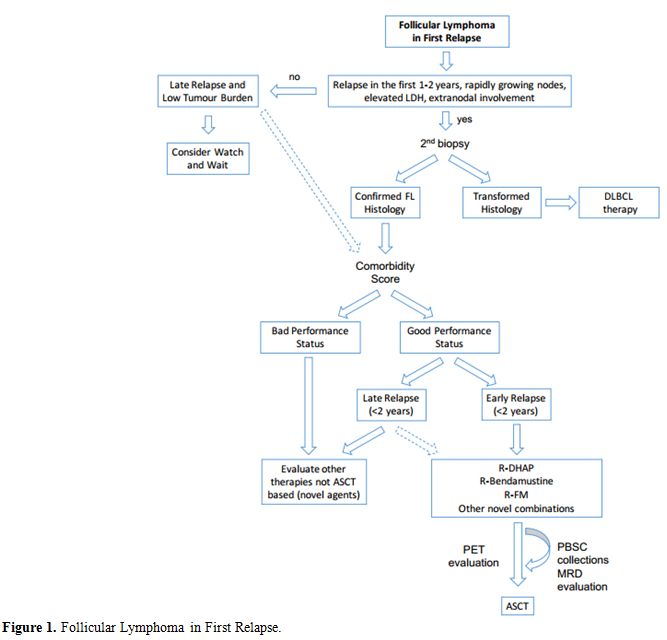

Although the significant therapeutic advances achieved over the last years, approximately 40% of all FL patients relapse in a different way and at different time after the first line.[12,18] A recent study showed a dismal clinical outcome among FL patients relapsed in the first year after R-CHOP with a 5-year OS rate of 34% (95% CI, 19% to 60%), confirming the early relapse as an indirect parameter of refractoriness and poor outcome.[35] Based on these data, it is crucial to provide the best salvage therapy for these high-risk and early relapsed FL patients. Conversely, the FL patients who relapse after more than two years are associated with a very favorable survival with a 5-year OS of 94%,[12,35,36] and the indication for ASCT as salvage treatment in this subgroup is not clear.[37] In fact, the treatment choice (ASCT versus other less intensive regimens) should always be based on patient symptoms, disease burden such as the presence of bulky disease and/or extranodal involvement, and/or signs of rapidly progressive lymphoma. For patients relapsed after 2 years, intense salvage therapies including ASCT are usually delayed. In case, localized relapse may be managed by the radiotherapy alone and/or monoclonal antibodies postponing more intense approaches. For this purpose, a careful staging is mandatory in all relapsed FL. Figure 1 summarizes our current approach to FL in first relapse after immunochemotherapy.

|

Figure 1. Follicular Lymphoma in First Relapse. |

FL can transform into an aggressive lymphoma at different

times.[38] For this reason, all early relapsed FL

and/or those with

rapidly growing nodes, elevated LDH and/or significant extra-nodal

involvement, should be investigated to rule out a potential

transformation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). In this

relapsed setting, the differential diagnosis is mandatory, because the

biological and clinical behavior of transformed FL is similar to the

one of the DLBCL, thus requiring intensive chemotherapy and ASCT.[39]

Before

starting any treatment, an important element to consider other than

histologic transformation is the patient comorbidity status. In fact,

intense salvage schemes and ASCT consolidation should be avoided in old

(≥ 65-70 years) and/or frail patients, considering the risk of

significant toxicity and complications. Nevertheless, the definition of

elderly or frail is not unique, as addressed in the last paragraph of

this review.

In the case of young and fit early relapsed FL

patients, high dose chemotherapy approaches plus ASCT consolidation

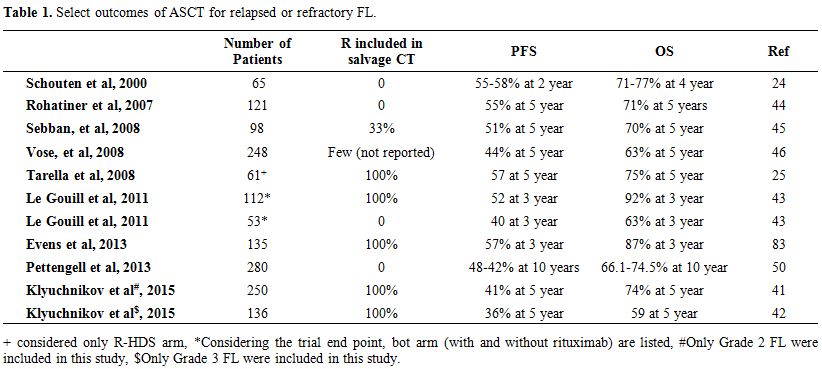

showed the best results in terms of OS and PFS (Table 1).[24,25,40-46]

This outcome was further improved by adding rituximab into intense

salvage regimens. A GITMO retrospective analysis reported a 5-year EFS

and OS of 65% and 80%, respectively, among refractory and early

relapsed FL treated with Rituximab in combination with high-dose

sequential therapy (R-HDS).[25] Similar results were

achieved in late

relapsed FL cases with a 5-year EFS and OS of 71% and 83%. Overall

these data showed a significant improvement compared to the HDS

regimens without rituximab (5-year EFS and OS of 23% and 41%,

respectively among early relapsed and 33% and 65% respectively among

late relapsed FL patients). In this retrospective study authors also

included rituximab naïve relapsed FL patients, and this may partially

explain excellent results. Nevertheless, in a subanalysis including

together all DLBCL and FL previously treated with rituximab, the 5-year

EFS, and OS were 44% and 56%, respectively. Considering previously

published studies (Table 1)

including relapsed FL patients, the 5-year PFS after high dose regimens

and ASCT consolidation is approximately 40-50%. Furthermore, it is well

known that the addition of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies is able to

improve the MRD-negative peripheral stem cell harvests and,

consequently, the survival and the rate of MRs after ASCT.[7,8,47-50]

|

Table 1. Select outcomes of ASCT for relapsed or refractory FL. |

In the last 10 years, different alternative less toxic approaches were tested among relapsed/refractory FL. Bendamustine represents one of the most important agents with a reported overall response rate (ORR) of 81% and a median PFS of approximately 8 months as a single agent in relapsed FL patients.[51] Interestingly, the combination of Rituximab plus Bendamustine in the first line did not show any inferiority compared to R-CHOP, confirming the high efficacy of this agent and its strong synergistic activity with rituximab.[30,32,33,51-54] Fludarabine-containing regimens still remain a valid option, although their use should be carefully evaluated considering the high rate of early and late toxic adverse events.[55] An effective agent in relapsed FL is represented by radio-immunotherapy (i.e., Zevalin®) that should be considered preferentially in non-bulky relapse with a bone marrow infiltration <20%.[56,57]

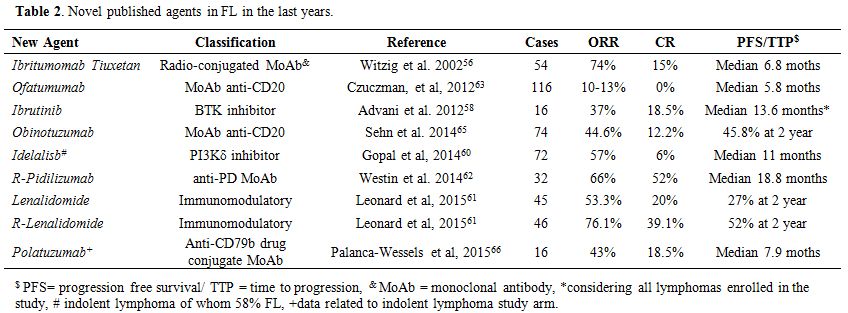

Most recently, several novel molecules have shown an interesting activity in relapsed/refractory FL patients (Table 2).[12] Particularly, lenalidomide, pidilizumab, and idelalisib demonstrated a strong activity and an acceptable toxic profile also when combined with rituximab.[58-62] In addition, few novel and potentially more active anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (GA-101 and Ofatumumab) are currently under investigation,[63-65] as well as novel conjugated monoclonal antibodies (i.e., Polatuzumab).[66] Overall, these new molecules are progressively bringing significant changes in relapsed FL management, and they may improve the outcome in the next future. A challenging issue is how to integrate these drugs into the therapeutic strategy and how to combine them with chemotherapy. In fact, although these molecules are not defined as “conventional chemotherapy”, they may be responsible for very important and unknown toxicities. As a matter of fact, two different trials testing the combination of novel agents [Pi3K inhibitor (Idelalisib) + Immunomodulatory agent (Lenalidomide) and Pi3K inhibitor (Idelalisib) + Syk Inhibitor (Entospletinib)] were recently interrupted for unacceptable toxicity and adverse event incidence.[67,68] In the future, it is conceivable that new non-chemotherapic drugs will change the salvage therapy paradigm in FL completely. However, although a significant fraction of relapsed and heavily pretreated FL patients achieved disease reduction when treated with these novel agents, the median PFS has never reached in most of the experiences the survival reported in ASCT studies, so far (Table 1-2). Moreover, ASCT is well known to induce long-term remission in approximately 40-50% of patients. For these reasons, we believe that ASCT still represents the current standard of care of young and fit FL patients in first and early relapse.

|

Table 2. Novel published agents in FL in the last years. |

Conditioning Regimens for Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

The conditioning regimen represents one of the most important therapeutic factors to obtain the best response after ASCT. The most used conditioning regimens are based on high dose chemotherapy, TBI–containing regimen and more recently the combination of chemotherapy and radio-immunotherapy. Although there are not any significant data for a specific conditioning regimen, the use of total-body irradiation (TBI) is associated with a higher risk of secondary malignancy after transplant compared to the chemotherapy-based conditioning regimen.[22,23] Specifically, in the setting of ASCT, the relative risk of therapy-related myelodysplasias or leukemia development was four times more in the TBI-containing group compared to others.[23] For this reason, this approach has been progressively abandoned. Conversely, radio-immunotherapy, and in particular 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) represents a valid option not only for the peculiar efficacy that exploits the radiosensitivity of lymphoma cells but also for its safety and acceptable toxic profile.[56,57,69] This agent was included in myeloablative conditioning to increase the anti-lymphoma activity of ASCT, in particular in high tumor burden and/or refractory patients at the time of transplant.[70,71] Although the early results are promising, it is not clear what is the real advantage of this combination.

In order to extend the number of patients eligible to ASCT, considering the frequent old age of FL patients, differently less toxic conditioning regimens have been explored in the last years. High dose 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (0.8-1.2 mCi/kg) consolidation after five high dose chemotherapy courses showed promising results among frail and/or elderly series of relapsed and naïve B-lymphomas patients.[72,73] Although the early toxicity profile and the outcome was excellent; the updated results showed an 8-year cumulative incidence of the secondary myelodysplastic syndrome of 9.4%, suggesting an increased risk compared with what was previously reported among younger patients receiving high-dose therapy and autograft. On the other hand, a high incidence of myeloid cancers was not clearly observed when Zevalin® was administered at the standard dose.

Despite

the high efficacy of ASCT salvage programs in FL, a significant

fraction of patients still relapse. To further improve the efficacy of

ASCT, different post-transplant therapeutic approaches have been

explored. Rituximab post-transplant maintenance is probably the most

important one.[36,47,48,74,75] However, conversely to what reported in

the first line, there is no sufficient evidence supporting the use of

rituximab maintenance in all FL patients achieving a response after

autologous ASCT. A potential setting may be represented by FL patients

that do not achieve MRD negativity after transplant. In a small report,

it was shown that the percentage of MRs might be increased by a short

rituximab consolidation. Further prospective validations are needed to

confirm these data.[36,47,48,74,75]

Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

AlloSCT represents an effective treatment for relapsed and refractory FL with 5-years OS ranging from 50-80%.[16] Historical studies that compared PFS curves of patients who received ASCT or alloSCT reported a statistically significant advantage for allografted patients. However, the lower relapse risk with alloSCT was offset by the higher TRM compared with ASCT, leading to similar 5-year OS rates of 51%-62%.[76-78] For this reason, the best choice in first relapse patients is still represented by ASCT (Figure 1), as previously mentioned. Taking into account that about 30-50% of autografted patients relapse afterward, alloSCT represents an effective salvage strategy that should always be considered in these patients. Retrospective data on myeloablative alloSCT in FL showed a high and quite unacceptable toxicity and TRM incidence.[76-78] For this reason, in the past, alloSCT was generally avoided in the majority of relapsed/refractory FL patients that were usually excluded from myeloablative transplant programs due to the age older than 50-55 years. In order to extend the fraction of eligible FL patients and to reduce the TRM, different less toxic and more feasible conditioning regimens and transplant strategies have been explored. In the last twenty years, the most important change in transplant approach has been represented by the introduction of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens which are associated with a reduced TRM without a loss of efficacy provided by the GVL effect.[16,17,79] Thanks to these qualities, RIC alloSCT extended the application of allotransplant to a larger rate of FL patients that were historically considered ineligible, including also patients older than 60 years old. The first MD Anderson RIC allogeneic SCT study in indolent B-cell lymphomas showed that a conditioning regimen containing fludarabine and cyclophosphamide could provide stable engraftment of donor cells with a low TRM rate.[79] This study showed a 2-years OS of 80% that was impressive considering that the patients were highly pre-treated and refractory. A recent update of this study confirmed this excellent outcome with an estimated EFS and OS of 83% and 85%, respectively, after a median follow-up of 60 months.[80] Subsequently, other studies confirmed RIC efficacy and feasibility in relapsed/refractory FL patients, suggesting the existence of a strong immune-mediated antitumor activity (Table 3).[81-92] Indeed, the GVL effect emerged to be superior in patients affected by FL compared to those affected by other lymphomas such as DLBCL.[81] As a matter of fact, FL represents the only hematological disorders where alloSCT is not contraindicated in case of active disease before transplant. Indeed, several studies show that alloSCT can achieve long-term remissions and a potential disease eradication in approximately 40-50% of FL patients with refractory and active disease before transplant.[93] This high alloSCT immune activity was further confirmed by the additional evidence of clinical and molecular responses after the withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy or donor lymphocyte infusions.[80]

|

Table 3. A summary of outcomes of allo-SCT for relapsed or refractory FL underwent alloSCT |

A recent multicentre retrospective study included 183

relapsed/refractory after ASCT FL patients who received alloSCT

RIC.[88] The 5-year PFS and OS were 47.7% and 51.1%,

respectively, with

an acute GVHD cumulative incidence of 45% at 100 days and a 2-year

chronic GVHD cumulative incidence of 51.2%. After a median follow-up of

58.8 months (range 3-159), the overall TRM was 24%. Overall, these data

confirmed the efficacy of alloSCT among post ASCT relapsed FL patients

and, it underlined that TRM and GVHD remain a big issue that affects

approximately a quarter of all FL receiving a RIC alloSCT.

Over

the years, the TRM incidence decreased thanks to a better understanding

of the GVHD and a more accurate diagnosis and management of infectious

complications. In particular, the T-cell depletion has been shown to

decrease GVHD-related toxicity and mortality, without affecting the

relapse risk after transplant.[17] Unfortunately,

despite the

introduction of these new transplant strategies, acute and chronic GVHD

still represent an important issue and thus novel integrated drugs are

currently being explored in alloSCT setting. MD Anderson Cancer Centre

showed an interesting and favorable outcome of the inclusion of

anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody before and after transplant.[80,94] Other

clinical trials are currently investigating how rituximab and novel

monoclonal antibodies may improve the immunosuppression without

affecting the GVL activity.

Historically, a good HLA-identical

donor (sibling or unrelated) is available only for 50-60% of patients,

thus representing one of the main alloSCT limitations. Recently, novel

transplant approaches have been developed to use an alternative donor

in lymphoma patients. Haploidentical donors have been used for many

years, mostly after extensive T-cell depletion of peripheral stem

cells, to avoid the risk of GVHD. However, this kind of regimen was

affected by an unacceptable infectious toxicity and a low feasibility

that significantly limited their extensive use in the clinical

practice.[95] Recently, the introduction of T

cell-repleted

haploidentical transplant using post-transplant cyclophosphamide has

shown an interesting combination of low toxicity and low GVHD incidence

compared to the historical haploidentical T-depleted SCT.[95-101]

Furthermore, a large retrospective study recently suggested that there

were no significant differences regarding GVHD incidence and toxic

events between haploidentical T-cell repleted SCT and HLA-matched

unrelated donors.[102] This new approach may

guarantee the availability

of a potential donor for all FL patients, extending the proportion of

refractory and relapsed FL patients potentially eligible to alloSCT.

As

well as in ASCT setting, significant efforts were performed in order to

improve the anti-lymphoma activity of conditioning regimens without

affecting neither the immunosuppression nor the GVL process. Excluding

the previously cited rituximab-based RIC regimens, two main drugs have

been successfully included in conditioning regimens: bendamustine and

Zevalin®. Bendamustine combines the alkylating activity of the mustard

group with the antimetabolite activity of the analog purine structure,

and for this reason, it provides both a potential antitumor and

immunosuppression activity. Considering these peculiar characteristics,

MD Anderson tested a new RIC bendamustine-based for indolent lymphomas.

The results are impressive, with 2-year OS and PFS rate of 90% and 75%,

respectively, after a median follow-up of 26 months (range, 6-50

months).[103] Interestingly, the incidence of acute

grade II-IV GVHD

was 11%, and the 2-year rate of extensive chronic GVHD was 26%. Ongoing

different clinical trials are exploring novel bendamustine alloSCT

conditioning regimens to evaluate the major potential benefit and low

toxicity effect compared to the historical fludarabine-based regimens.

Zevalin®, as mentioned before, represents a well-known active therapy

in relapsed FL. Similarly to ASCT, some groups investigated the role of

radio-immunotherapy into the alloSCT conditioning regimens.[94] An

interesting combination of (90)Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (0.4 mCi/kg) and

one of the most used fludarabine-based RIC regimens, ((90)YFC) showed a

cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD at 100 days of 17%

(±11%) and chronic GVHD at 12 months of 63% (±19%). The 2-year

non-relapse mortality was 18% (±12%), and 2-year OS, and PFS were 83%

(±11%) and 74% (±13%), respectively. Although this novel conditioning

regimen looks promising, It still needs to be established whether

inclusion of radioimmunotherapy in the alloSCT program can

significantly improve the final post alloSCT outcome.

The FL

biology knowledge is constantly improving, and novel pathogenetic

mechanisms and biological subgroups have been described thanks to

innovative genomic approaches.[38] In the next

future, this improvement

will provide new potential therapeutic targets and may help discover

distinct molecular features possibly associated with poorer or better

outcome after alloSCT. For example, the recent study of Kotsiou E. et

al. represents an early and very interesting example of this. Authors

reported a favorable post alloSCT outcome associated with TNFRSF14

aberrations that affect 40% of all FL patients.[104]

This is the first

demonstration of how a specific tumor genetic lesion may affect the

capacity of tumor cells to stimulate allogeneic T-cell immune

responses, generating wider consequences for adoptive immunotherapy

strategies.

Considering all these data, in our current clinical

practice we candidate all eligible FL patients who relapse after ASCT

to alloSCT (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Follicular Lymphoma Relapsed after ASCT. |

Transplant: is Always an Age Issue?

Overall,

alloSCT and ASCT anti-lymphoma efficacy are well established among

young/fit relapsed FL patients. The OS and PFS results after these

approaches have never been reached by any novel new drugs.

Nevertheless, the long-term outcome of transplanted patients may be

affected by late toxic events, especially in the alloSCT setting. In

this scenario, a correct and multidisciplinary evaluation of the

performance status and comorbidities of all relapsed FL patients should

always be provided before the transplant, as well as a careful

long-term follow-up after SCT. During the last years, several studies

have highlighted that the sole age is not enough to exclude patients

from more intense salvage approaches such as BMT. Different comorbidity

scores have been proposed to stratify the risk of toxic and adverse

events related to high-dose chemotherapy regimens.[105-110]

Overall,

these scores showed how relapsed FL patients older than 65 years but

with a low number of comorbidities may have a significant benefit from

intensive chemotherapy regimens without an excess of toxicity. This is

possibly due to RIC regimens, better supportive care and less toxic

pre-transplant treatments both in ASCT and in alloSCT setting. The most

used score in the alloSCT setting is represented by the hematopoietic

cell transplantation comorbidity score (HCT-CI).[106]

This score is

able to predict the TRM of patients undergoing an alloSCT, regardless

of disease status. Recently, the HCT-CI was updated including age

through different parameters.[109] The age threshold

was 40 years old,

confirming that among the over 40 years old patients, age was not

sufficient to assess and stratify the risk of toxicity. Having more

than half of FL patients older than 60 years old, this score should be

applied in all the patients undergoing an alloSCT.

The

importance of patient comorbidity status straightened the role of

timing in transplant decision-making. The transplant has not to be

considered as a “magic wand” able to eradicate lymphoma cells in every

time and every condition. The transplant outcome depends on many

factors: delaying alloSCT or ASCT to subsequent relapses exposes

patients to other salvage therapies, other potential comorbidities, as

well as problems in donor availability. In conclusion, if we have an

advanced early relapsed FL patient with a low comorbidity index, ASCT

should not be delayed and alloSCT should be performed as soon as the

patient achieves the best response after ASCT relapse.

Conclusion

The continuous introduction of novel and effective therapies is rapidly changing the traditional approaches to different hematological cancers. As well as other lymphoproliferative disease, also FL is strongly involved by these advancements. The incorporation of novel agents in the anti-lymphoma therapy will hopefully improve our current approach to relapsed FL patients, and eventually partially overcome the actual BMT indications.[37] Nevertheless, until now, no novel drugs or combinations have shown a superior or non-inferior clinical outcome compared to the results of ASCT and alloSCT in relapsed/refractory FL patients. Unfortunately, transplant-based therapies are still affected by significant toxicities and for this reason, a carefully and multidisciplinary evaluation should always be provided to select eligible relapsed FL patients rightly.

References

[TOP]