Kayıhan Pala, Harika Gerçek, Tuncay Aydin Taş, Rukiye Çakir, Sedef Özgüç And Timur Yildiz

1 Public

Health Department, Uludag University Faculty of Medicine, Bursa, Turkey

2 Nilufer

Tuberculosis Control Association Dispensary, Bursa, Turkey

Corresponding

author: Tuncay AYDIN TAŞ, MD, Public Health Department, Uludag

University Faculty of Medicine, Bursa, Turkey. Tel: +90 02242954281,

E-mail:

taydintas@uludag.edu.tr

Published:

November 1, 2016

Received: June 6, 2016

Accepted: October 23, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016059, DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2016.059

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is

an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Objective: The

aim of this study is to describe the epidemiological and clinical

aspects of patients who applied to the Bursa Nilufer Tuberculosis

Dispensary by investigating the trends in epidemics over three decades.

Method:

In this retrospective observational study, the records of all

tuberculosis cases (1630 patients) treated in the last 30 years

(1985-2014) at the Bursa Nilufer Tuberculosis Dispensary were examined

and statistically analyzed.

Results:

Males comprised 65.2% of the patients. The ages of the patients ranged

from 1 to 87 years, and the mean age was 37.4 (95% CI: 36.6-38.2).

Among the cases, 86.7% were new infections and 74.1% were pulmonary

tuberculosis. In the last decade, the education level, the percentage

of patients who had received a BCG vaccination, the proportion of women

and active employees among them increased (p<0.05), while it

decreased among men (p<0.05). Clinical symptoms accompanying TB

such

as weakness, anorexia, weight loss, and cough, decreased to a

statistically significant degree (p<0.05). In the last decade,

the

mortality rate was 3.6% and increased compared with previous decades

(p<0.05). Mortality was higher among patients who were elderly,

male, did not have a BCG scar or had a chronic disease (p<0.05).

Conclusion: This

study adds information about the change of TB epidemics in Turkey in

the last 30 years. Further studies are needed to determine the risk

factors associated with tuberculosis mortality and to evaluate the

effectiveness control programs of this disease.

|

Introduction

Tuberculosis

(TB) is a disease that primarily affects the lungs, but it can spread

to extrapulmonary organs through lymphogenic and hematogenous routes.1

Approximately one-third of the world population has an asymptomatic and

non-infectious latent infection. About 10% of these asymptomatic

patients progress to active disease and approximately 45% of

individuals with the active disease die if it is not treated.[1,2]

The

World Medical Association emphasizes that poverty fuels the spread of

tuberculosis by causing limited access to primary health care services,

inducing malnutrition, and inadequate living conditions; therefore,

tuberculosis should be considered as a disease of poverty and

inequality.[3]

Despite notable progress in the past decade,

tuberculosis is still a public health concern in most of the countries

within the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region. Countries

outside of the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA)

still suffer from high rates of TB and multidrug-resistant TB, while

EU/EEA countries have a significant number of TB cases among vulnerable

population groups, such as people of foreign origin and prisoners. In

2014, an estimated 340 000 incident cases of TB (range 320 000–350 000)

occurred in the WHO European Region, equivalent to 37 cases (35–38) per

100 000 population. This number represents about 3.6% of the total

burden in the world. About 83% of incident TB cases in 2014 occurred in

the 18 high-priority countries.[4]

Turkey is one of the 18

high-priority countries.

The first data regarding the

epidemiological situation of tuberculosis in Turkey pertained to the

year 1950. TB mortality, which was 204/100.000 in 1950, decreased to

8.8/100.000 in 1980 and 1.6/100.000 in 2000. While the tuberculosis

incidence was 177/100.000 according to the values for 1960, it dropped

to 24/100.000 in 2002.[5] In

Turkey, the estimated TB prevalence was

22/100.000, the incidence was 18/100.000, and the mortality was

0.61/100.000 for 2014.[6]

In Turkey, the TB control program began in

1918 under the guidance of Tuberculosis Control Associations, which

were voluntary organizations, and have been maintained via vertical

structuring within the Ministry of Health and provincial

organizations.[7] Public Health Law

(No. 1593, 1930) designated

tuberculosis as a notifiable disease and made its treatment free of

charge. In Turkey, information regarding the patients comes primarily

from the records of Tuberculosis Control Dispensaries (TCDs). Valuable

information resources are also the general death records and the

results of epidemiologic studies. Since 2007, the Department of

Tuberculosis Control has collected information regarding patients

registered at the TCDs and has published them as reports.[8]

TCDs

are the health institutions that provide diagnosis, treatment,

follow-up and control, patient notification, registration, archiving

and statistics, immunizations, screening, drugs, training, health

education activities, social welfare, coordination, and consultancy.[9]

The TCD follows the guidelines of "Stop TB Strategy" and the

"International Standards for Tuberculosis Care" adopted by the WHO.[10]

Bursa

Nilufer Tuberculosis Control Dispensary was established as the Bursa

Tuberculosis Control Association in 1948 and was included among public

interest associations in 1949.[11]

Since its service building moved

from the city center to the Nilufer district in 2003, the Association

has provided services as the Nilufer Tuberculosis Control Association

Dispensary.[12]

The dispensary case series are relevant for determining the current

situation of tuberculosis in Turkish.

In

this study, we analyzed socio-demographic characteristics, the clinical

findings, diagnosis and treatment processes and treatment results of

the patients who applied to Bursa Nilüfer

Tuberculosis Control

Dispensary (NTCD) in a period of thirty years.

Material

and Method

Bursa

is the fourth most populous city (1.8 million) in Turkey and is located

in Northwestern Anatolia in Turkey. Nilufer is one of the three central

districts of Bursa which was established on the western side of the

city. Nilufer is the newest and most planned and organized district of

Bursa; it is the most rapidly urbanizing area of the city, and its

population is slight over 300.000. The Nilufer ranks the first place

amongst the districts of Bursa significantly contributing to the

economy of Turkey and Bursa. The first Organized Industrial Zone of

Turkey has been established within the district of Nilufer in 1961.

There are twenty-three Family Health Centre, one Community Health

Center, one Tuberculosis Control Dispensary and two public hospitals in

Nilufer.

This descriptive study was carried out between June 2014

and February 2015. The files of all cases (1662 people) receiving

tuberculosis treatment in Nilufer Tuberculosis Control Dispensary

(NTCD) were reviewed, comprising the treatments of the last 30 years

(1985-2014). Thirty-two patients who had started treatment of

tuberculosis were later diagnosed carriers of another disease and then

excluded from this study. Therefore only the data of 1,630 patients

were evaluated.

TB cases were diagnosed both in Dispensary and

public hospitals. Pulmonary TB was diagnosed by X-ray, smear microscopy

of sputum and sputum culture. The most commonly used media for the

isolation of tuberculosis were solid egg-based (Löwenstein–Jensen,

Ogawa) and agar-based (Middlebrook 7H10 or 7H11) media; manual liquid

synthetic (Middlebrook 7H9) and automated liquid media (Bact/Alert 3D,

MGIT 960, VersaTREC). Non-pulmonary TB was diagnosed only in hospitals.

According to legislation in Turkey, patients diagnosed of TB in

hospitals referred to the regional dispensary for receiving TB

treatment. In 30 years there was no change in the definitive TB

diagnosis (X-ray, smear microscopy of sputum and sputum culture) in

Dispensary; but there is no information in defining TB diagnosis

methods in the hospitals in the dispenser records.

In this study,

were retrospectively examined the tuberculosis patient registers,

tuberculosis patient monitoring vouchers, patient examination forms and

computer records. The data obtained were included in a data collection

form consisting of 48 questions. The patients’ socio-demographic

information (age, gender, marital status, educational status,

profession, work conditions, social security status), the presence of

chronic disease, TB history, the history of contact with a tuberculosis

patient, the presence of a Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) scar,

symptoms accompanying the diagnosis, case description, reason for

examination, TB locations and treatment result were examined in this

form. The underlying concepts and definitions used in this study were

based on the "T. R. Ministry of Health Tuberculosis Diagnosis and

Treatment Guidelines 2011".[10]

The occupations of working patients

were classified according to the International Standard Classification

of Occupations ISCO 08.

Drug resistance has been evaluated in

patients since mid-1990’s. TB resistance was determined by drug

susceptibility testing. In the laboratory, drug susceptibility testing

of TB isolates was performed by the proportion methods (agar based MB

7H10/11, Löwenstein Jensen); automated fluid systems (MGIT 960,

VersaTREK) and molecular methods (Real-time PCR, reverse

hybridization). Multidrug-resistant TB is resistant to at least

isoniazid and rifampin. Patients with the following characteristics

were considered at risk of MDR-TB:

• Failure of retreatment regimens,

• Chronic TB cases,

• Exposure to a known MDR-TB case,

• Failure of first-line chemotherapy,

• Relapse and return after default

without recent treatment failure, and

• History of using poor or unknown

quality TB drugs.

TB

treatment has been changing for the last 30 years period in the

dispensary. In the first two decades nine-month treatment regimens were

applied (in the first two months isoniazid, rifampin,

pyrazinamide, and ethambutol or streptomycin and then for 7 months

isoniazid and rifampin). In the last decade, a six-months standard TB

treatment was applied. Standard TB treatment includes the use of 4

drugs: rifampin, pyrazinamide, isoniazid, and ethambutol given for two

months, followed by a rifampin/isoniazid continuation phase for an

additional four months.

The permission for the study was received

from Uludağ University, Faculty of Medicine, Ethics Committee (dated

June 10, 2014, and numbered 2014-12/3).

The

research data were evaluated using the SPSS 18.0 software package. The

descriptive statistics, chi-square test, chi-squared test for trend and

Fisher's exact test were employed in the data analysis. A p-value less

than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The

total number of 1630 TB cases received tuberculosis treatment in NTCD

from 1985 through 2014. When the patients were grouped into three

periods of ten years (classified according to when the patient file was

opened), 627 patients were diagnosed from 1985-1994, 490 from

1995-2004, and 513 from 2005-2014. 65.2% of the patients were male, and

the male/female ratio was 1.88. The patients’ ages ranged from 1 to 87

years; the mean age was 37.4 (95% G.A.: 36.6-38.2). The gender and age

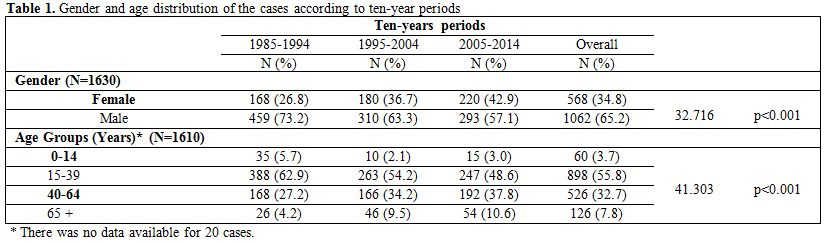

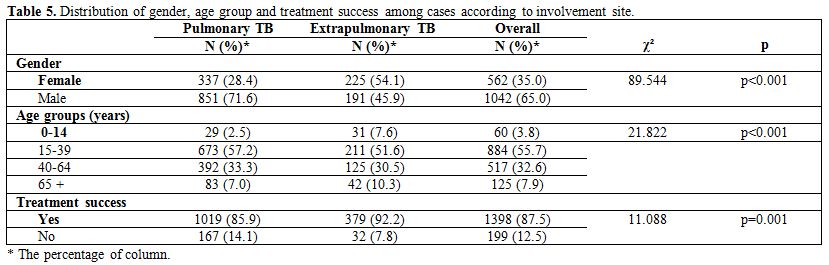

distribution of the cases are shown in Table 1 and

socio-demographic characteristics of the cases according to sex and

ten-year periods are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 1. Gender and age distribution of the

cases according to ten-year periods |

|

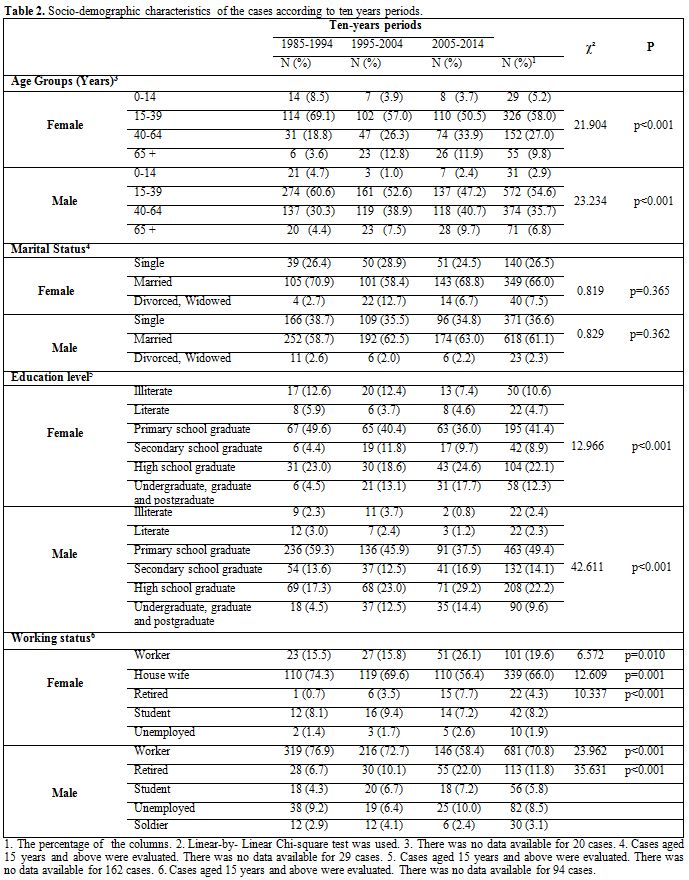

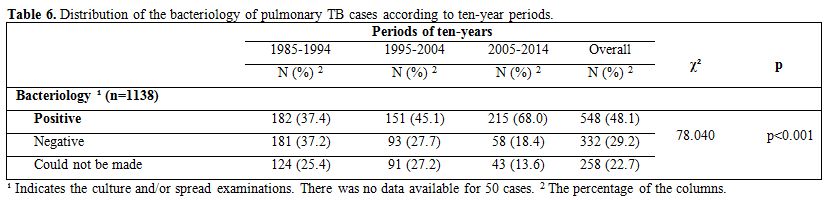

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of

the cases according to ten years periods. |

According

to Dispensary records, 1572 cases were born in Turkey (96.4%), the rest

of them were born in eleven different countries (Bulgaria, Greece,

Yugoslavia, Turkmenistan, Georgia, Macedonia, Saudi Arabia, Uzbekistan,

Ethiopia, Azerbaijan, Iraq) except Syria. There were no refugees from

Syria receiving TB treatment in the NTCD.

The most frequently

systemic symptom observed was coughing (72.1%). Night sweating was

observed in 49.6%, sputum in 46.3%, hemoptysis in 14.9%, fever in 7.9%,

and side pain in 3.1%. Allegations of malaise, anorexia, weight loss

and coughing decreased in the last decade compared with the previous

ten-year periods; however, complaints of back pain increased in the

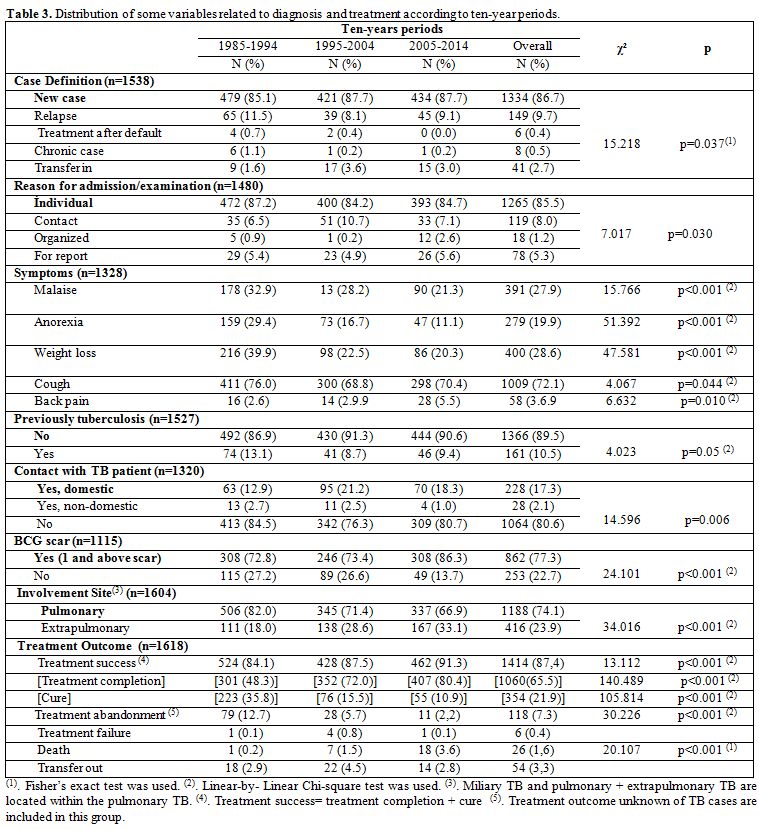

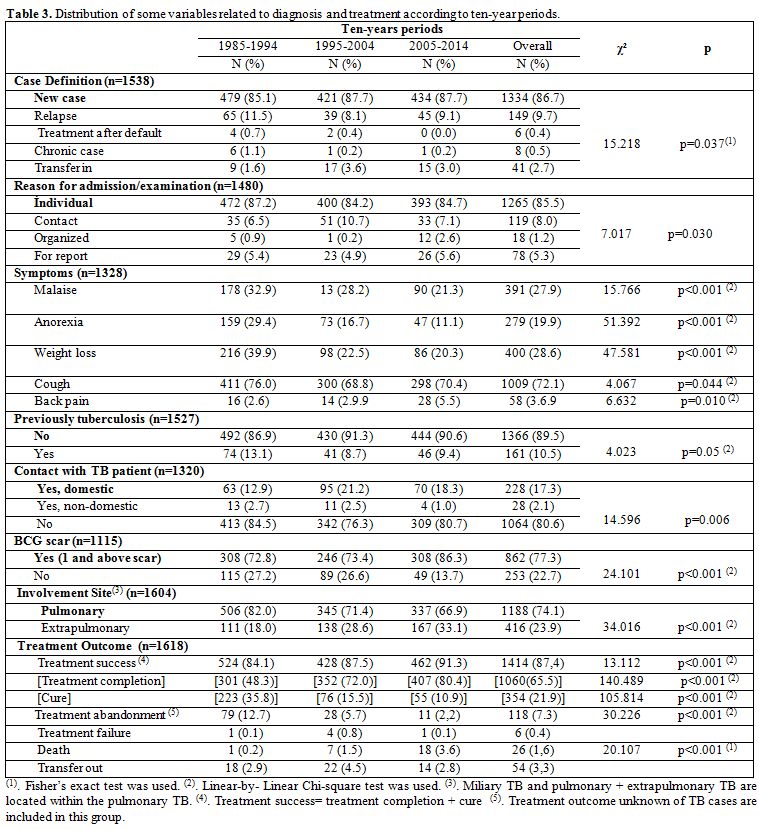

years (Table 3).

The main characteristics of TB cases related to diagnosis and treatment

are shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3. Distribution of some variables related

to diagnosis and treatment according to ten-year periods. |

The

relapse rate was 1.7% in the 0 -14 year age group compared with 15.4%

in the 40-64 year age group (p<0.001); it was 11.8% in pulmonary

TB cases compared with 3.8% in extra pulmonary TB cases

(p<0.001).

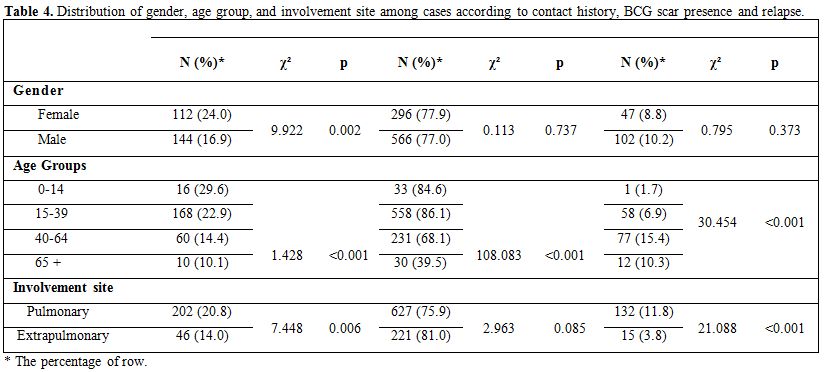

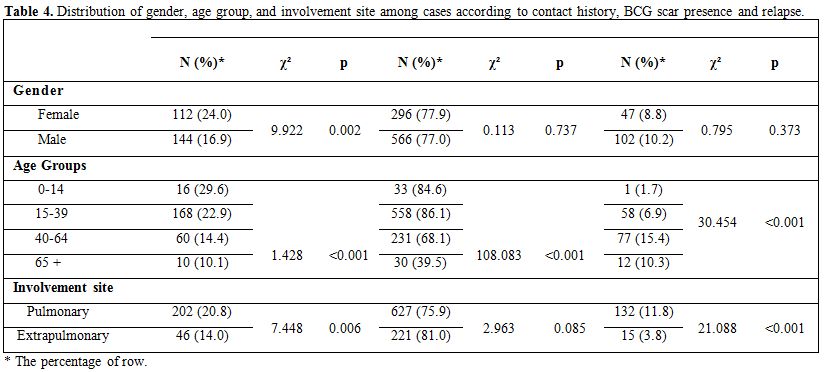

The relapse rate, BCG scar presence, and contact history are shown

according to gender, age group and involvement site in Table 4.

Domestic

contact was determined for all children (0-14 year age group). Among

all adult females, the non-contact was 77.1%, domestic contact was 21%,

and the non-domestic contact was 1.9 %; among all adult males, the

non-contact was 83.6, the domestic contact was 14.4 %, and the

non-domestic contact was 2% in men (p=0.014).

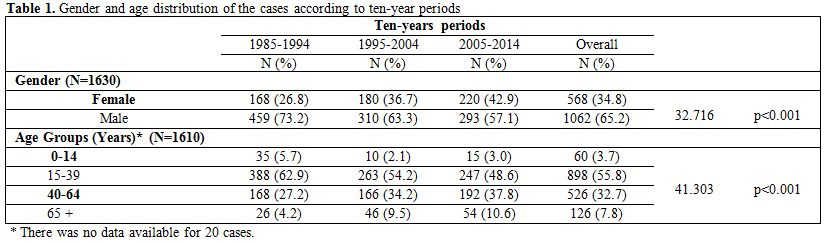

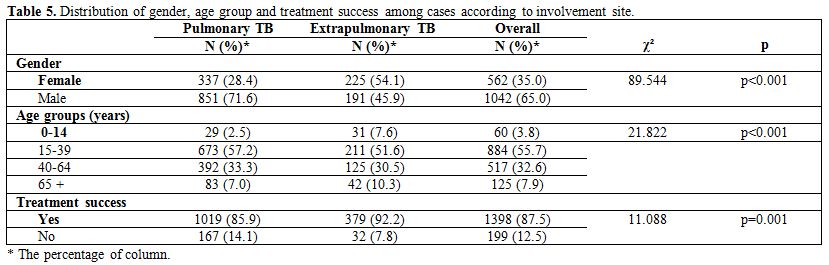

The site involvement in relation to gender, age group, and treatment

success is shown in Table 5.

|

Table

4. Distribution of gender, age group, and involvement site among cases

according to contact history, BCG scar presence and relapse. |

|

Table 5. Distribution of gender, age group and

treatment success among cases according to involvement site. |

Involvement

of the pleura was found in 11.5% of the cases, lymph node involvement

in 9.2%, bone involvement in 1.6% and genitourinary system involvement

in 1.6%.

All of the 26 deaths occurred in patients aged 40 years and

older. The mortality rate was significantly higher among elderly (over

65) people compared to 40-64 age groups (p<0.001), males

(p=0.038),

patients without a BCG scar (p=0.012), patients with multi-drug

resistant TB (p=0.033) and those with chronic diseases (p<0.001).

When

the BCG scar was analysed according to ten-year periods, the proportion

of patients with a BCG scar of the 15-39 year age group decreased from

72.9% in the first ten years to 55.7% in the most recent decade, and

the proportions among those aged 40-64 years and over 65 years

increased from 19.8% to 34.1% and from 1.0% to 6.9%, respectively

(p<0.001).

Twenty-four percent (1035) of the TB patients had at

least one chronic disease (No information about chronic diseases were

available for 595 patients). The presence of chronic diseases in TB

cases have risen from 11,3% in the first decade to 26,6% in the second

decade and 37,6% in last decade respectively (p<0.001). The

accompanying chronic diseases were: diabetes mellitus in 31.3%;

hypertension in 16.9%; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),

asthma and respiratory illness including chronic bronchitis in 14.1%

and heart disease in 9.2%.

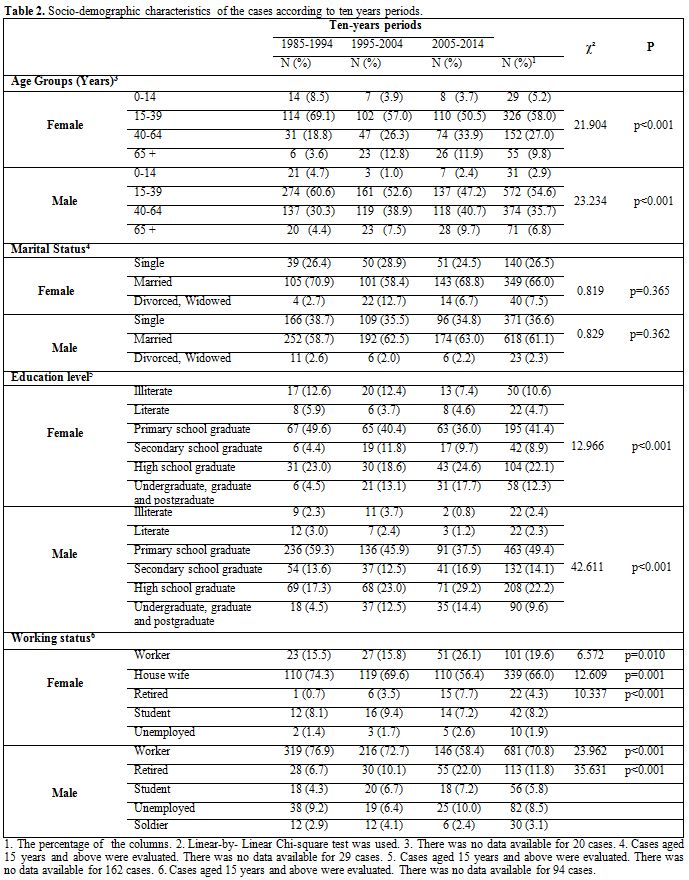

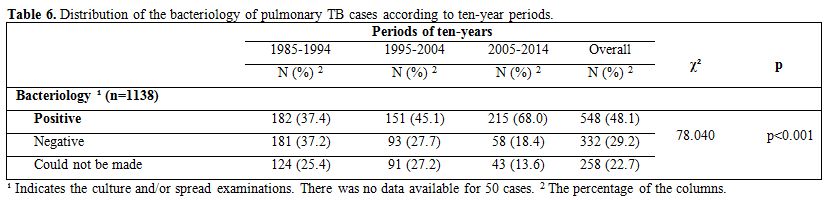

Culture

and/or microscopic examinations could not be performed for 22.7% of the

patients with pulmonary TB. In these cases, TB was diagnosed with

clinical suspicion, X-rays, and ex juvantibus therapy. The proportion

of pulmonary TB cases with positive bacteriology significantly

increased (p<0.001) over the most recent decade (Table 6).

|

Table 6. Distribution of the bacteriology of

pulmonary TB cases according to ten-year periods. |

Among

the new pulmonary TB cases with positive bacteriology, treatment

success was experienced by 80.7% during the first decade, 86.8% during

the second decade and 92.1% during the third decade (p=0.003).

Drug

resistance was examined in 198 cases, and multi-drug resistant TB was

positive in 6.1%. There is no significant difference between ten-year

periods regarding multi-drug resistant TB (p=0.666).

Discussion

In

the most recent decade, the number of patients diagnosed with

tuberculosis at the NTCD was lower than in the first 10 years but

higher than in the second decade. In the 1980s, the incidence of TB in

our country was greater compared to the second decade as well as other

developing countries. TB incidence has decreased in second decade due

to impact of the fight against tuberculosis and socio-economic

development. However, the fight against TB has declined in the last

decade in Turkey; for example, some dispensaries have been closed by

Ministry of Health. Both closure of a Dispensary in Bursa and the

increase in population due to internal migration in City may have led

to increasing the number of patients in last decade.

Social Security

Institution (SSI) patients were registered at TCDs with the transfer of

SSI hospitals to the Ministry of Health.[8]

These changes of this

study, although parallel the rises and falls throughout all the Turkey,

may be related to the patient registration and notification system, the

related screening programs, patients' applications to the TCDs and the

registering of SSI patients in the national TB program.

Similar to

other studies carried out in Turkey and throughout the world, this

study found a higher proportion of males than females among TB patients

(throughout Turkey, 58.6%; in the USA, 62%).[13-18]

Men are more

likely than women to participate in social and working life and

therefore more often exposed to infection. In addition to male- and

female-specific biological and epidemiological differences, the low

number of female tuberculosis case notifications can be explained with

to the difficulties that woman face in access to health services due to

various socio-economic and cultural factors.[19-21]

In this study, the

proportion of female patients was significantly higher in the most

recent decade compared with the previous ten-year periods. This datum

can be explained by an increase of females’ participation in social

life and work life and improved access to health services as well as

with a real increase in incidence of TB due to worsening economic and

living conditions.

The age distribution of tuberculosis patients is

also an important indicator in determining the changes in TB's

epidemiology. In developed countries, tuberculosis is most common among

the elderly and mostly results from the reactivation of a previous

primary infection; however, in developing countries, TB affects all age

groups, especially youth and young adults.[22-24]

Throughout Turkey,

5.4% of those who received treatment between 2005 and 2011 were in the

0-14 year age group, 58.3% were in the 15-44 year age group, and 11.1%

were in the 65 and over age group.[17]

In the USA, 5% of tuberculosis

patients are below the age of 15 years, 40% of them are in the 15-44

year age group, and 24% of them are over 65 year-old.[18]

In our study,

although the majority of the patients were in the 15-44 year age group,

in line with nationwide studies of Turkey and other studies, the

proportion of patients who were younger than 15 years was

lower.[14,17,25] When ten-year periods were

compared, the proportion of

patients who were below the age of 15 years was significantly lower in

the first decade than in the most recent decade whereas that of the

45-64 year age group and the over 65 age was higher. Although this

indicates that the disease moved from the young age group towards an

older age group, the change may have resulted from the ageing of the

population, the fact that elderly people are more prone to infections

and the difficulty of diagnosing tuberculosis infections in childhood

in the past.[23,24,26]

A low level of education is a risk factor for

TB at the individual level.[27] In

studies carried out in Van and

Isparta in Turkey, the proportions of TB cases with an elementary

educational attainment or below are 83.3% and 66.3%, respectively

higher than in this study (54.9%).[28,29]

The proportion of patients

with nine or more years of education increased linearly between

ten-year periods for females (p=0.005) and males (p<0.001). This

increase may have been related to the increase in the general education

level of the patients who visited the NTCD and of the country’s

population in general; furthermore, it indicates that tuberculosis does

not affect only people with lower educational levels.

The

percentages of occupation, business and working status along and the

indicators related to the working lives of the patients varied across

the studies. In this study, the percentage of unemployed patients was

6.2%, which was lower than in other studies. The percentage of employed

patients was 53.0%, which was higher than in other studies.[14,19]

In a

study carried out in North America, TB was associated with working in

non-professional jobs and with unemployment.[27]

In this study, the

percentage of those working in jobs that did not require qualification

was significantly higher among workers, and the increase in this

category in the most recent decade was statistically significant. The

sociocultural characteristics of the patients, poor working conditions

in jobs that did not require qualification, subcontracted labor,

crowded living conditions and screening programs in workplaces are

considered important reasons for this increase.

The relapsed cases

can be related to insufficient previous treatment, re-exposure to

infections, endogenous reactivation of pulmonary or extrapulmonary

focus of infection among TB patients and having multidrug-resistant TB.

In a study carried out in Brazil, the relapse rate was reported as 5.5%

and was associated with high mortality.[30]

This study had a lower

percentage of new cases than other studies, but a higher relapse

rate.[14,29]

The relapse rate decreased in the second decade, tended to

increase in the third decade and was significantly higher among

patients aged 40 years and older. The high relapse rate may have been

due to the high rate of treatment abandonment or happens because the

directly observed treatment could not be implemented effectively, or

because of inadequate or inappropriate treatment regimens, drug

resistance, or advanced age.

The most contagious patients produce

living TB bacilli with sputum. The contact time with a patient

producing Koch bacilli and the intensity of the bacilli are the risk

factors in the development of infection.[31]

The reported history of

contact is 8.5%, 13.5% and 38.8% in various studies.[14,15,29] The

present study found that the history of contact was high in females and

children with pulmonary tuberculosis, similar to other

studies.[26,32,33]

In this study, the patients’ contact rate with

tuberculosis patients was higher in the last decade than in the first

decade and was lower than in the second decade (p=0.006). Among the

patients as a whole, TB contact history rate was 19.4%, but diagnosed

by contact examination for TB rate was 8% and this rate was higher in

the last decade than in the first decade but lower than in the second

decade (p=0.030). The contact examinations are important for

identifying hidden TB patients who do not visit the dispensary or who

wait until late presenter patients and children who are infected as a

result of close contact with infectious adult and adolescent TB

patients. The high contact rate in the NTCD region paired with a low

contact examination rate means that it is necessary to improve contact

examinations. In Turkey, the percentage of extrapulmonary TB cases was

reported to be 27.0% in 2005, 36.8% in 2011 and 36.0% in 2014.[6,17]

In

2011, 27.3% of the male patients and 50.2% of the female patients had

extrapulmonary involvement.[17] In

the study by Özkara et al. in 108

dispensaries, the rate of extrapulmonary TB was reported to vary

between 14.8% and 28.4% between provinces.[34]

In this study, although

the rate of extrapulmonary TB was significantly lower in males, relapse

cases and patients with a history of contact in the last decade, it was

significantly higher in females[14,35,36] and those younger than 15

years[35] and most frequently

showed pleura and lymph node

involvement,[30,37]

similar to some domestic and foreign studies. In

studies carried out in the United States and Brazil, drug resistance

was reported to be low in extrapulmonary TB patients.[30,36]

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis can be affected by comorbidities that cause

immunodeficiency, such as HIV infection; patient characteristics;

endocrine factors; immunological and genetic susceptibilities; and

differences in endemic tuberculosis strains by population and

geographical region, and these factors should be identified.[30,35,36]

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis had different epidemiological

characteristics and risk factors from pulmonary tuberculosis; it can

become infectious if it spreads to the lungs, but it is otherwise not

infective. Therefore, it is important to determine the risk factors of

extrapulmonary tuberculosis for early diagnosis and treatment.

In

this study, similar to others, TB cases were most often accompanied by

coughing symptoms upon admission in 25.4% to 80% of patients (in

Isparta in Turkey 25.4%, in Los Angeles 72.7%, in Samsun in Turkey 80%

of patients).[29,38,39]

In different studies, the other symptoms upon

admission were weight loss in 44.5% to 62.9%, anorexia in 11.7% to

59.7%, night sweating in 16% to 54.0% and fever in 52.3%.[29,38,39]

In

the study carried out in Los Angeles, the presence of coughing, fever,

weight loss and hemoptysis was associated with health insecurity and a

negative tuberculin skin test.[38]

The complaints of malaise

(p<0.001), anorexia (p<0.001), weight loss

(p<0.001) and

coughing (p=0.044) decreased in the most recent decade compared with

the previous decades. These findings may indicate that diagnosing TB

based on classic symptoms is less possible.

The

meta-analysis by Colditz et al. reported that the BCG vaccine decreased

the tuberculosis infection risk by an average of 52.0-74.0% and also

decreased the deaths from lung tuberculosis, meningitis, miliary and

tuberculosis in newborns.[40]

However, the BCG vaccine does not protect

from primary infection or reactivation of latent pulmonary

tuberculosis, which is the main source for the spread of the bacilli in

the community.[41] In a study

carried out in Izmir, the percentage of

0-14- year-olds with a BCG scar was determined to be 74.6%.[33] In the

present study, the proportion of patients with a BCG scar was 84.6%

among the 0-14 age group and was significantly lower among those aged

40 years and older. The overall percentage of patients with a BCG scar

and the percentage of patients aged 40 years and older with a BCG scar

have increased at a statistically significant rate in the most recent

decade. This increase may also occur due to vaccination of some cases

in BCG campaigns across the country that took place between 1953 and

1967.[42] There was no significant

difference between those with a BCG

scar and those without a BCG scar regarding pulmonary and

extrapulmonary organ involvement. Among those with BCG scar, the

mortality rate was significantly lower. Along with the need for further

studies that demonstrate the protectiveness of the BCG vaccine and its

effect on mortality, these results suggest the need for other, more

effective vaccines to prevent latent tuberculosis as well.

The WHO

aims to identify at least 70% of smear-positive tuberculosis patients

bacteriologically and to treat at least 85% of them successfully. The

percentages of treatment success and case identification are the

outcomes used to measure the effectiveness of tuberculosis

control.[43,44] In this study,

among patients with pulmonary TB, the

percentages with examined bacteriologically and positive bacteriology

were 77.3% and 62.3%, respectively, which are consistent with the

values determined in other studies.[34,39]

In the study by Özkara et

al.,[34] the treatment success of

new pulmonary TB cases with positive

bacteriology was 82.5%, which is lower than the value determined in the

present study (87.1%). In the present study, while treatment success

was significantly higher in the most recent decade than in the previous

decades, the percentages of patients who were cured and those who

abandoned treatment were significantly lower. “Treatment success” means

the total of treatment completion and cure rates. The increase of the

treatment success may result from decrease in treatment abandonment

along with the increase in treatment completion. The lack of request

for bacteriological examination in the end of therapy and the patients

who were unable to sputum specimens could be the reason for low cure

rates.

A study

carried out in Brazil found that being over the age of 40 years,

concomitant HIV infection, illiteracy, severe extrapulmonary TB and

re-treatment after relapse were risk factors associated with

mortality.[30] In this study, all

of the 26 observed deaths occurred in

patients aged 40 years and older. There was no significant difference

in mortality between the pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB patients. The

overall mortality rate was 3.6% in the most recent decade, which was

significantly higher than that of the previous decades

(p<0.001).

The fact that the mortality rates were significantly lower in the past

decades may arise from an inability to determine deaths because of high

rates of treatment abandonment and low presence of chronic diseases.

The mortality rate was high among elderly people (p<0.001),

males

(p=0.038), patients without a BCG scar (p=0.012), patients with

multi-drug resistant TB (p=0.033) and patients with accompanying

chronic diseases (p<0.001). All of the deaths were accompanied

by at

least one chronic illness. The increase in mortality rates among

patients treated at the NTCD may have resulted from the growth in the

elderly population. This age group has a higher risk of contracting TB,

but more frequently presents the masking of the symptoms for

comorbidities, a late diagnosis arising from a lack of sufficient care,

and a low compliance and the occasional use of drugs because of their

side effects. Further studies are needed to determine risk factors and

the reasons for the recent increase of mortality to reduce the spread

of TB and the deaths.

Strengths

and Limitations of the Study

The

fact that the study covers an extensive period of 30 years and the high

number of cases reported is the strength of this survey, which analyzes

only the data and risk factors that were defined in the records. The TB

patients treated at the NTCD were not only residents of the Nilufer

district of Bursa but also of some other districts that the dispensary

serves. Therefore, the TB prevalence and incidence for the Nilufer

district could not be calculated in this study.

Conclusion

The

fact that the study covers an extensive period of 30 years and the high

number of cases reported is the strength of this survey, which analyzes

only the data and risk factors that were defined in the records. The TB

patients treated at the NTCD were not only residents of the Nilufer

district of Bursa but also of some other districts that the dispensary

serves. Therefore, the TB prevalence and incidence for the Nilufer

district could not be calculated in this study.The number of patients

treated for tuberculosis in the NTCD was lower in the most recent

decade than in the first decade of the survey and higher than in the

second decade. In the last ten years, the proportion of females,

elderly people and patients with nine years of education or more

increased significantly, and of workers among female patients. However,

low income countries should further reduce the obstacles related to

gender in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis by making

structural and social changes, such as increasing women's socioeconomic

circumstances and education levels, reducing discrimination and

implementing strategies to remove gender inequalities in health.

Unfortunately, the mortality rate also significantly increased probably

determined by higher number, pulmonary tuberculosis with positive

bacteriology, of elderly people, with accompanying chronic diseases,

resistance to antibiotic could also have a role.

It is necessary to increase the efficiency of the control programs and

laboratories to detect patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and

efficiently treat them avoiding their contact with risk groups,

infants, older and immunodeficient people. These procedures could

reduce the spread of infection within the community. The effectiveness

of tuberculosis control programs can improve by continuous training of

health workers and population, and by functioning of a registration

system should to ensure the reliability of patient data. It is

necessary to design extensive epidemiological studies that examine the

effectiveness of the fight against tuberculosis also in low-income

countries, the risk factors and patient mortality and reveal the causal

factors. It must not be forgotten that tuberculosis is a social disease

that is affected by the inequality in health, and efforts should be

made to bring services to patients who cannot reach healthcare services

on their own.

References

- World Health

Organization. WHO tuberculosis. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/

(Accessed 02/11/2015).

- World

Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf?ua=1

- World

Medical Association. Physicians advised to treat

tuberculosis as a disease of poverty. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/40news/20archives/2015/2015_43/index.html

(Accessed 25/12/2015).

- European

Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office

for Europe. Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2016.

Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2016.

Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/tuberculosis-surveillance-monitoring-Europe-2015.pdf

(Accessed 29/08/2016)

.

- Vidinel

I. A historical view to tuberculosis in Turkey In: Bilgic H,

Karadag M, eds. Toraks Kitaplari Tiberkoloz. Istanbul, AVES Yayincilik.

2010; 17-24. (in Turkish)

- World

Health Organization. WHO tuberculosis. Available from:

<https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports?op=Replet&name=/WHO_HQ_Reports/G2/PROD/EXT/TBCountryProfile&ISO2=TR&outtype=html

(Accessed: 29/11/2015).

- �zkan

S. Basic Institution of fight against tuberculosis in our

country: Tuberculosis Dispensary In: Bilgic H, Karadag M, eds. Toraks

Kitaplari T�berk�loz. Istanbul, AVES Yayincilik. 2010; 680-686. (in

Turkish).

- �zkara

S. Tuberculosis Epidemiology in Turkey. In: Bilgic H, Karadag M,

eds. Toraks Kitaplari Tiberkoloz. Istanbul, AVES Yayincilik. 2010;

36-47. (in Turkish)

- �zdemir

T, Torkkani MH, Yilmaz Aydin L , Balci o, Danacibas R, Bilgin

A. Provincial assessment in the scope of the tuberculosis control

program. Tuberk Toraks. 2014;62(3):183-190. DOI: 10.5578/tt.7899. Epub

2014 August 7. http://www.tuberktoraks.org/linkout.aspx?pmid=25492815

- T.

R. Ministry of Health Tuberculosis Diagnosis and Treatment

Guidelines 2011. In: Akdag R, eds. Ankara, Basak Matbaacilik ve Tanitim

Hizmetleri Ltd. Sti. 2011;1. (in Turkish)

- Turkish

Republic Official Newspaper. Available from: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/main.aspx?home=http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/7110.pdf&main=http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/7110.pdf

(Accessed : 01/04/2016).

- Turkish

Rebuplic Ministry of Health Department of Tuberculosis 16.09.2003 tarih

ve 7546 sayili yazisi. (in Turkish).

- Ko�akoglu

S, Simsek Z, Ceylan E. Epidemiologic characteristics of the

tuberculosis cases followed up at Sanliurfa central tuberculosis

control dispensary between 2001 and 2006 years. Turkish Thoracic

Journal. 2009;10:9-14 http://www.turkishthoracicjournal.com/FullText/416/epidemiologic_characteristics_of_the_tuberculosis_cases_fol

l

- Orman

A, �nl� M, Cirit M. Assessment of 627 tuberculosis cases observed

in Afyon tuberculosis dispensary between 1990 and 2000. Respiratory

Diseases. 2002;13 (4):271-276. http://www.respiratorydiseasesjournal.org/text.php3?id=184

- Martinez

AN, Rhee JT, Small PM, Behr MA. Sex differences in the

epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis.

2000;4(1):26–31. PMid:10654640

- �ift�i

F, Bozkanat E, Ilvan A, Kartaloglu Z, Sezer O, Kaliskan T, Kaya

H. The year of 2003 treatment results of soldier patients with

tuberculosis in a military hospital which has feature of the referance.

Turk Thorac J. 2006;7(1):45-50.

- Turkish

Republic Ministry of Health, Public Health Institution of

Turkey Department of Tuberculosis. Tuberculosis struggle in Turkey 2013

Report: In: Özkan S, Musaonbasioglu S, eds. Ankara, Uzman Matbaacilik,

2014. (in Turkish).

- CDC.

Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, October 2015 .

Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2014/pdfs/tb-surveillance-2014-report.pdf

- Borgdorff

MW, Nagelkerke NJD, Dye C, Nunn P. Gender and tuberculosis: a

comparison of prevalence surveys with notification data to explore sex

differences in case detection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000

Feb;4(2):123-32. PMid:10694090

- Neyrolles

O, Murci LO. Sexual inequality in tuberculosis. PLoS Medicine

2009;6(12):1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000199

PMid:20027210 PMCid:PMC2788129

- Hudelson

P. Gender differentials in tuberculosis: the role of

socio-economic and cultural factors. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996

Oct;77(5):391-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0962-8479(96)90110-0

- Tatar

D, Keskin p, zacar R, Halilolar H. Similarity and differences

of tuberculosis in the young and the elderly patients. Tuberculosis and

Thorax. 2002; 50: 485-91.

http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=17&ref_ind_id=246

http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=17&ref_ind_id=246

- Öztop

A, tnsal I, Genay T, Özge A, kakmak R, Uoku R. The

epidemiological characteristics of tuberculosis patients registered in

Kahramanlar dispensary between 1999 and 2003. Respiratory Diseases.

2006;17(3):123-132. http://www.respiratorydiseasesjournal.org/pdf/pdf_SHD_332.pdf

- Kili�aslan

Z. Epidemiology of Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis in the

World. In: Bilgic H, Karadag M, eds. Toraks Kitaplari Tuberkoloz.

Istanbul, AVES Yayincilik. 2010; 25-35. (in Turkish).

- Kiter

G, Coskunol I, Alptekin S. Evaluation of tuberculosis patients

enrolled to Esrefpasa tuberculosis dispensary between january 1997 to

june 1998. Tuberculosis and Thorax . 2000; 48(4): 333-339. http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=9&ref_ind_id=111

- Sen

V, Uluca , Yilmaz S, Selimoglu Sen H, Tuncel T, Genes A, Karabel

M, Garkan MF. The evaluation of the clinical and laboratory

characteristics of children with pulmonary tuberculosi. Dicle Medical

Journal. 2014; 41(3): 552-557. http://dx.doi.org/10.5798/diclemedj.0921.2014.03.0473

- Young

BN, Rendon A, Rosas A, Baker J, Healy M , Gross JM , Long J ,

Burgos M , Hunley KL. The effects of socioeconomic status, clinical

factors, and genetic ancestry on pulmonary tuberculosis disease in

northeastern mexico. PLOS ONE 2014; 9(4): 1-8. Epub 2014 April 11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094303

- �zbay

B, Sezgi C, Altin�z O, Sertogullarindan B, Tokg�z N. Evaluation

of tuberculosis cases detected in our region between 1999 and 2003.

Tuberculosis and Thorax. 2008;56(4):396-404. http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=41&ref_ind_id=624

- Zengin

E, Kisioglu AN, S�nmez Y. The characteristics of tuberculosis

cases which registered in Isparta central district tuberculosis

dispensary and the sufficiency situation of dispensary registries: 2000

to 2007 years . SD� Tip Fak�ltesi Dergisi 2009;16(3):14-18. (in

Turkish). http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/sdutfd/article/view/1089001618/1089001643

- Gomes

NMDF, Bastos MCDM, Marins RM, et al. Differences between risk

factors associated with tuberculosis treatment abandonment and

mortality. Pulmonary Medicine, vol. 2015, Article ID 546106, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/546106

- �zt�rk

R. Natural Resistance in Tuberculosis and Risk Factors,

Tuberculosis Semposioum in the 21th Century and 2nd Course of

Tuberculosis Diagnosis Methods in the Laboratory Samsun: 2003.

Available from: http://www.klimik.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/982011124221-Recep_Ozturk.pdf

(Accessed: 13/01/2016). (in Turkish)

- Aksel

N, Mertoglu A, Dogan H. Comparison of the male and female cases

with pulmonary tuberculosis. Izmir Gegos Hastanesi Dergisi.

2008;22(2):35-45. http://www.igh.dergisi.org/pdf/pdf_IGH_111.pdf

- Tatar

D, Alptekin S, Coskunol I, Aydin M, Arslangiray S. The

retrospective analysis of tuberculosis in children followed up at Izmir

Esrefpasa dispensary between 1995-2000.Respiratory Diseases.

2002;13(2):94-100. http://www.respiratorydiseasesjournal.org/text.php3?id=154

- �zkara

S, Kiliraslan Z, Oztark F, Seymenoglu S , Erdogan AR ,Tellioglu

C ,Kosan AA, Kaya B, Kologlu F ,Kibaroglu E. Tuberculosis in Turkey

with regional data. Turkish Thorasic Journal. 2002;3(2):178-87. http://www.turkishthoracicjournal.com/FullText/969/tuberculosis_in_turkey_with_regional_data

- Forssbohm

M, Zwahlen M, Loddenkemper R, Rieder HL . Demographic

characteristics of patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis in

Germany. European Respiratory Journal 2008 Jan;31(1):99-105. Epub 2007

Sep 5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00020607

- Peto

HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, LoBue PA, Armstrong LR. Epidemiology

of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993–2006. Clin

Infect Dis. 2009;49(9):1350-1357.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/49/9/1350.full.pdf html http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/605559

- Kolsuz

M, Ersoy S, Demircan N, Metintas M, Erginel S, Alatas F, Urgun

I. The evaluation of pulmonary tuberculosis patients enrolled to

Eskisehir Deliklitas tuberculosis control dispensary. Tuberculosis and

Thorax. 2003;51(2):163-170 http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=20&ref_ind_id=295

- Miller

LG, Asch SM, Emily IY, Knowles L, Gelberg L, Davidson P. A

population-based survey of tuberculosis symptoms: how atypical are

atypical presentations? Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(2):293-299. doi:

10.1086/313651. http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/30/2/293.full.pdf+html

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/313651

- Kayhan

S. Demographic and clinical characteristics of tuberculosis: A

report of 2404 cases at a referral hospital. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res.

2012;6(9):2033-2037

- Coldwitz

GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F, Brewer TF, Wilson ME, Burdick E,

Fineberg HV. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of

newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses

of the published literature. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1):29-35. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/96/1/29.full.pdf

- World

Health Organization Geneva. WHO car Vaccine [online]. Weekly

epidemiological record, 2004;79:25-40. Available from: http://www.who.int/wer/2007/wer8221.pdf

PMid:14768304

- Kili�aslan

Z, Kologlu F. The Role of the Tuberculosis Society Fight

against TB in Turkey. In: Bilgic H, Karadag M, eds. Toraks Kitaplari

Tiberkoloz. Istanbul, AVES Yayincilik. 2010; 673-679. (in Turkish).

- World

Health Organization. Stop TB Partnership and World Health

Organization. The Global Plan to Stop TB, 2006-2015: actions for life

towards a world free of tuberculosis. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/global/plan/globalplanfinal.pdf

- Jordan

TS, Davies PD. Clinical tuberculosis and treatment outcomes. Int

J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010;14(6):683-8. PMid:20487604

[TOP]

http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=17&ref_ind_id=246

http://www.tuberktoraks.org/abstracttext.aspx?issue_id=17&ref_ind_id=246