Received: August 12, 2016

Accepted: October 25, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016061, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.061

This article is available on PDF format at:

Antonella Anastasia and Giuseppe Rossi

SC Ematologia e Dipartimento di Oncologia Clinica, A.O. Spedali Civili, 25123 Brescia, Italy.

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most

common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and constitutes 15% to 30% of

lymphoma diagnoses. The natural history of the disease is characterized

by recurrent relapses and progressively shorter remissions with a

median survival of 10yrs. The impossibility of achieving a definite

cure, have prompted investigations into the possible role of more

active and less toxic strategies with innovative therapeutic agents. Recently Casulo et al. demonstrated that approximately 20% of patients with FL relapse within two years after achieving remission with R-CHOP and have a poor prognosis. It is conceivable that this particularly chemoresistant population would benefit from specifically targeting the biologic and genetic factors that likely contribute to their poor prognosis. Evolving strategies for difficult to treat FL patients have recently considered immunomodulatory agents, new monoclonal antibodies as well as drugs targeting selective intracellular pathways. The importance of targeting the microenvironment together with the malignant FL cell has been particularly underscored. We review the most promising approaches, such as combining anti-CD20 antibodies with immunomodulatory drugs (Lenalidomide), mAbs directed against other surface antigens such as CD22 and CD23 (Epratuzumab, Lumiliximab), immunomodulatory antibodies such as PD-1, or inhibitors of key steps in the B-cell receptor pathway signaling such as PI3K inhibitors (Idelalisib, Duvelisib). Another highly attractive approach is the application of the bi-specific T-cell engaging (BiTE) antibody blinatumomab which targets both CD19 and CD3 antigens. Moreover, we highlight the potential of these therapies, taking into account their toxicity. Of course, we must wait for Phase III trials results to confirm the benefit of these new treatment strategies toward a new era of chemotherapy-free treatment for follicular lymphoma. |

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and constitutes 15% to 30% of lymphoma diagnoses. Its median survival is approaching ten years. The natural history of the disease is characterized by recurrent relapses and progressively shorter remissions. The impossibility of achieving a definite cure using the currently available chemo-immunotherapy regimens, as well as with more intensive treatments, such as high-dose therapy plus stem cell transplantation, have prompted investigations into the possible role of innovative therapeutic agents with more activity and less adverse events. Avoiding the toxic effects of chemotherapy would also be desirable for a disease with a relatively indolent course, where quality of-life is of primary importance, particularly in the elderly population.[1]

In addition, there are subsets of FL patients with a more aggressive disease who would also benefit from alternative treatment strategies. Recently, the US National LymphoCare Study have published data which show that approximately 20% of patients with FL relapse within two years from achieving remission with R-CHOP and have a poor prognosis, independent of that predicted by the FL International Prognostic Index (FLIPI). Their 5-year overall survival (OS) was only 50% compared to 90% in patients who had a longer treatment response.[2]

It is conceivable that this particularly chemo-resistant population would benefit from specifically targeting the biologic and genetic factors that likely contribute to the poor prognosis of this group. Indeed, the biological characteristics of FL and, more importantly, of its microenvironment, significantly impact on prognosis and may also play a significant role in determining FL sensitivity to treatments. A gene expression signature of the non-malignant stromal cells has been reported; that was prognostically more important than gene signatures deriving from the neoplastic B-cells.[3]

More recently, Pastore et Al. found that mutations in seven genes (EZH2, ARID1A, MEF2B, EP300, FOXO1, CREBBP, and CARD11), coupled with clinical parameters of FLIPI score and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, were able to identify subgroups of FL patients with a distinct worse prognosis. This clinicogenetic risk model was termed m7-FLIPI.[4]

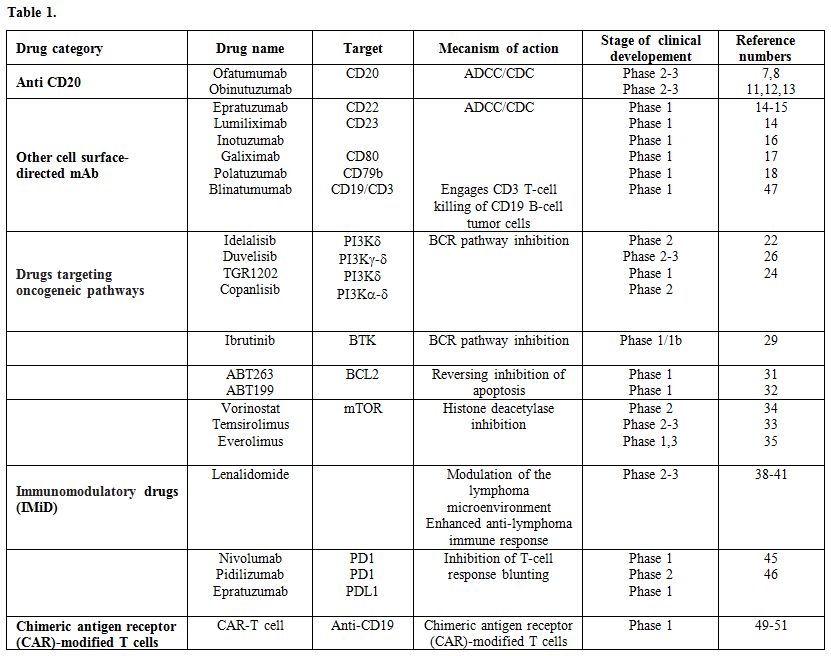

With the expanding knowledge of the pathogenesis of B-cell malignancies, in the last few years, several new therapies acting through a variety of mechanisms have shown promising results. We will briefly review the evidence available on these new drugs, which include new monoclonal antibodies and immunoconjugates, the anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide, inhibitors of B-cell receptor pathway enzymes, such as ibrutinib, idelalisib, duvelisib and TGR-1202, BCL2 inhibitors, checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-Tcells (Table 1).

|

Table 1 |

New Generation mAbs

AntiCD20 mAbs: The search for a monoclonal antibody with a higher activity than rituximab has been particularly active in recent years.

Ofatumumab is a humanized, class I anti-CD20 agent with an increased complement dependent cytotoxicity compared with rituximab. It binds to a different CD20 epitope resulting in higher affinity and, theoretically, a higher activity in cases with low CD20 surface expression.[5] In a phase 3 trial including 116 FL patients previously treated with rituximab or rituximab-containing chemotherapy, ofatumumab monotherapy was well tolerated, but it showed an overall response rate (ORR) of only 10% in the 86 patients who received the highest dose (1000 mg/8 weekly doses).[6] However, in first-line, in a phase 2 trial of FL patients, ofatumumab, given at 1000mg per week for a month and subsequently 1000 mg every 2 months for 8 months, obtained an ORR of 86% (Complete response [CR] in 13%) with a 1-year PFS probability of 97% and a safety profile similar to rituximab.[7] It has also been administered as part of combination treatment; 59 patients with advanced-stage, previously untreated FL received ofatumumab plus CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) and attained an ORR of 100%, with CR in 62% of patients.[8]

Obinutuzumab (GA101) is another humanized anti-CD20 agent. It is a class II agent, and therefore, it has a higher antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and induces B-lymphocyte apoptosis more effectively than rituximab.[9]

In patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iNHL), eight cycles of obinutuzumab were administered (days 1 and 8 of the first cycle and day 1 of each subsequent cycle).[10] One arm received 1600 mg in the first cycle and 800 mg subsequently, while the other arm received 400 mg (flat dose), obtaining an ORR of 55% and 17% and a median PFS of 11.9 and 6 months, respectively. In a phase II study including R/R iNHL patients, an induction and maintenance courses of obinutuzumab (4 weekly doses of 1000 mg and then every 2 months for 2 years) were superior in terms of ORR (45% vs. 27%) but not PFS to induction and maintenance with rituximab at the standard 375 mg/m2.[11]

GADOLIN (NCT01059630) is a phase 3 study including 396 rituximab-refractory iNHL patients. This randomized trial compared bendamustine alone (120 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of every 28-day cycle for up to six cycles) with bendamustine (90mg/m2) combined with obinutuzumab (1000 mg on day 1 of every cycle and days 8 and 15 of the first cycle), followed by maintenance with obinutuzumab. Both arms obtained the same ORR (63% vs. 69%), but a longer PFS was seen with the combination regimen followed by maintenance in the 321 patients (81%) with FL (13.8 months vs. not reached, Hazard ratio 0.48 [0.34-0.68]), despite a similar OS at the time of first analysis (albeit with less than 2 years of follow-up).[12] Obinutuzumab-bendamustine was slightly more toxic, particularly due to an increased frequency of neutropenia (grade≥3 in 33%) and infusion reactions (grade≥3 in 8%), although there were fewer episodes of pneumonia (3%) and less thrombocytopenia (grade≥3 in 10%) than in the bendamustine monotherapy arm.

To date, the final results of the GAUSS Study, in which obinutuzumab (GA101) was prospectively compared with rituximab in a randomized fashion in relapsed indolent lymphoma, have been published.[13] Among patients with follicular lymphoma, ORR seemed higher for obinutuzumab than rituximab (44.6% v 33.3%; P .08). However, this difference did not translate into an improvement in progression-free survival. No new safety signals were observed for obinutuzumab, and the incidence of adverse events was balanced between arms, with the exception of infusion-related reactions and cough, which were higher in the obinutuzumab arm.

The use of obinutuzumab in first-line therapy is under investigation, recruitment has been completed for the GALLIUM study (NCT01332968), a phase 3 randomized trial, including 1400 patients with previously untreated iNHL, comparing obinutuzumab vs. rituximab with combination chemotherapy. The results are still unpublished, but the interim analysis seems positive.

Other B-lineage antigen-directed antibodies: Although targeting CD22 and CD23 by antibodies such as epratuzumab or lumiliximab was less successful when applied to single agents,[14] the combination of epratuzumab with rituximab induced significant response rates both in relapse and front-line therapy.[15] A similar activity was found when the CD22 antibody inotuzumab was conjugated with ozogamicin and its combination with rituximab.[16] Promising data were also achieved by combining the anti-CD 80 antibody Galiximab with rituximab in patients with untreated FL.[17]

However, most of the above mentioned agents did not show sufficient activity to be further developed beyond the stage of clinical phase II studies.

More

recently an anti-CD79B antibody has been successfully fused with the

microtubule-disrupting agent monomethyl auristatin E. The resulting

antibody-drug conjugate polatuzumab vedotin has undergone phase 1 and

preliminary phase 2 studies and is currently under further

investigation.[18]

Drugs Targeting Oncogenic Pathways

PI3K Inhibition:

PI3K are enzymes involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, DNA

repair, senescence, angiogenesis and cell metabolism. Through their

activation, cell surface signals are transmitted into the cytoplasm

and, by phosphorylating different downstream molecules, they activate

pathways such as BTK, AKT, PKC, NF-kappa-B and JNK/SAPK, which

ultimately result in cell survival and growth. Its specific targeting

has a strong rationale, given the interplay between lymphoma and

microenvironment in FL. Different PI3K isoforms can be found in

different cell types.[19]

Idelalisib is the

first orally bioavailable, active inhibitor specifically targeting the

delta isoform of PI3K, an enzyme downstream from the B cell receptor,

which eventually signals through AKT and mTOR.[20]

Idelalisib showed marked antitumor activity in patients with FL who had

not had a response to rituximab and an alkylating agent or had had a

relapse within six months after those therapies (double-refractory

patients). In a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study, 125 patients

with indolent non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas were enrolled, including 72 FL

patients refractory both to chemotherapy and rituximab.[21]

They received idelalisib, 150 mg twice daily, until disease

progression. The 57% response rate was much higher compared to

historical rituximab[22] results in the same setting

of refractory patients, with 14% meeting the criteria for a complete

response. The median time to response was 1.9 months, the median

duration of response was 12.5 months, and the median progression-free

survival was 11 months. The most common adverse events of grade 3 or

higher were neutropenia, in 27% of the patients, elevations in

aminotransferase levels in 13%, diarrhea in 13%, and pneumonia in 7%).[21]

The

results of this study led to the approval of idelalisib by the Food and

Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for

the treatment of FL relapsed after two previous lines of treatment (in

the case of the EMA approval, refractoriness to the two previous lines

of therapy is required).

However, because of an excess of severe

infections, including Cytomegalovirus reactivation and Pneumocystis

jirovecii pneumonia, in the idelalisib arm of three randomized trials,

the safety of idelalisib particularly in the first line setting, is

currently under reevaluation. Moreover, the association of idelalisib

with lenalidomide and rituximab caused prohibitive hepatic toxicity in

a phase I-II trial which had to be interrupted,[23]

underscoring the importance of an accurate evaluation of the risk

benefit ratio of any new or any combination of no cytostatic agents.

Other PI3k inhibitors currently under investigation include TGR-1202,

duvelisib, and copanlisib.

TGR-1202 is, like idelalisib, a

selective delta isoform inhibitor. However, unlike the later, it showed

very few autoimmune- mediated side effects in a recent analysis of 152

highly pretreated patients with CLL and NHL receiving TGR-1202 in

monotherapy or in combination with the new anti-CD20 ublituximab.[24] In the subgroup of R/R iNHL, the ORR was 49% in monotherapy and 71% (CR in 24%) when administered in combination.

Duvelisib

(IPI-145), a gamma and delta isoform inhibitor, showed an ORR of 65% in

a phase 1 dose-escalation study in patients with iNHL,[25] which successfully met the primary endpoint of the phase II DYNAMO study.

The

phase II study enrolled 129 patients with iNHL, which included

follicular lymphoma (n=83), small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL; n=28), and

marginal zone lymphoma (MZL; n=18). The ORRs in each of these groups,

respectively, were 41%, 68%, and 33%. The majority of adverse events

reported in the study were labeled as clinically manageable and

reversible.

Despite achieving the primary endpoint of the study,

the magnitude of benefit did not match Infinity's expectations. Based

on the results, the long-term outlook for the medication was adjusted,

studies exploring duvelisib in combination with venetoclax were paused,

and 21% of the organization's workforce was laid off as part of a

research and development restructuring.[26]

Copanlisib,

which inhibits the alfa and the delta isoform of PI3k, is also under

active investigation and results of ongoing trials with this

intravenously compound are awaited. To date, it seems to interfere with

glucose metabolism.

Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway inhibitors:

The BTK pathway represents a further very attractive target in B-cell

malignancies. Ibrutinib is the first-in-class among specific

BTK-inhibitors.[27]

In R/R FL, in an update of

the initial dose- escalation trial, ibrutinib monotherapy administered

once daily at the dose of 560 mg until progression or withdrawal, has

shown an ORR of 63% (CR in 38%) and a median PFS of 24 months. Among

refractory NHL of different histologic subtypes, only minor activity

was shown in patients with FL in contrast with patients with mantle

cell lymphoma or Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia, where results were much

more promising.[28] The combination of ibrutinib with

chemoimmunotherapy (ICT) as well as with other agents including the

combination of lenalidomide and rituximab is currently being tested.

The preliminary results of a phase I-Ib study of the combination of

ibrutinib with bendamustine and rituximab do not seem to confer a

significant advantage over BR alone, but the number of patients treated

was small.[29]

Phase 3 studies, such as SELENE

(NCT01974440), which randomizes patients with R/R FL or marginal zone

lymphoma to ICT (BR or RCHOP) with or without ibrutinib, are also

underway.

Bcl 2 inhibitors: Interesting data also emerged from agents interfering with the BCL2 family of proteins.

BCL2

is an antiapoptotic protein, typically overexpressed in lymphoma by the

presence of its characteristic translocation t(14;18), which involves

the BCL2 gene. However, anti-BCL2 drugs are proving active in a wide

variety of B-cell disorders.[30]

Promising

response rates were initially reported from a phase 1 study with

ABT-263 (navitoclax), which is, however, associated with

thrombocytopenia.[31] A better efficacy-toxicity

profile is revealed by the BH3 mimetic ABT-199 (venetoclax), already

approved by FDA for B-CLL, which, in a phase 1 study, showed an ORR of

48% as a single agent. Given the direct involvement of bcl-2 in the

pathogenesis of FL, the results achieved may be considered less

favourable than expected. However, owing to its good tolerability

profile, the combination of venetoclax with chemoimmunotherapy or other

active agents is actively investigated and may yield better results.[32]

A phase 1b/2 trial with venetoclax, obinutuzumab and polatuzumab

vedotin (NCT02611323) in R/R FL is currently recruiting patients.

Trials with obatoclax, another BCL2 inhibitor, are also ongoing

(NCT00438178, NCT00427856), but no results are available.

M-TOR inhibitors and histone-deacetylase inhibitors:

Temsirolimus is a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor,

approved for the treatment of MCL, but which has also shown activity in

FL. In 39 patients with R/R FL, at a weekly dose of 25 mg

(intravenously), temsirolimus achieved an ORR of 54% (CR in 24%) and

3-year PFS and OS probabilities of 26% and 72%, respectively. Grade ≥3

neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were seen in around 30% of patients

with all other toxicities, grade ≥3, occurring in ≤6% of patients.[33] Temsirolimus is currently undergoing phase 3 trials in association with bendamustine and rituximab by the German study group.

The

histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat has been studied in a phase II

study in relapsed indolent lymphomas, which included 39 patients with

FL, and demonstrated an encouraging 49% overall response rate with a

median progression-free survival of 20 months in this small cohort.[34]

Everolimus too showed promising results in the relapsed/refractory setting with an ORR of 84 and 60%.[35]

Immunomodulatory Drugs (IMiD)

Lenalidomide is one of the

most promising new agents in the treatment of FL. Its mechanism of

action is not fully understood but probably includes a modulation of

the lymphoma microenvironment and an enhanced anti-lymphoma immune

response.[36] After promising single-agent activity

was seen particularly in patients with refractoriness to prior

therapies (ORR 23%, the median time to antitumor response 3.6 months,

median PFS 4.4 months).[37]

Lenalidomide was

combined with rituximab in the so-called R-squared or R2 regimen. The

combination showed a higher ORR (76% vs. 53%) and longer time to

progression (2 vs. 1.1 years), with no increased toxicity than

lenalidomide alone.[38] In the front-line

setting, two recent publications reported results of phase 2 trials

with the R-squared scheme. In the first, ORR was 98% (CR in 87%) with a

3-year PFS probability of 78% in a sub- group of 50 FL patients (out of

110 iNHL patients).[39] The second trial carried out

by the CALGB revealed an ORR of 93% (CR in 72%) and a 2-year PFS

probability of 89% in 65 FL patients of whom only two discontinued

treatment due to progressive disease and four due to toxicity.[40]

The

same regimen has been subsequently compared with standard

chemoimmunotherapy in a randomized phase 3 study (RELEVANCE) in

untreated patients. Both arms are followed by a maintenance phase.

Accrual has been completed but results are still not available.[41]

Anti PD-1: Follicular lymphoma is characterized by a significant interplay between malignant cells and their microenvironment.[42]

PD-1

is a T-cell receptor which, upon binding its ligand (PD-L1 or PD-L2,

found on B-cells), blunts T-cell response. PD-1 expression is an escape

mechanism for a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies.[43]

The

observation that some FL patients might have a very long survival

without progressive disease after diagnosis and do not need

anti-lymphoma therapy for years underscores the potential role of the

activity of the immune system against the lymphoma cells. Although FL

CD20+ tumor cells do not directly express PD1 ligands, PD-L1+

histiocytes are present within the T-cell-rich zone of the neoplastic

follicles and contribute to the exhaustion of tumor PD1+ infiltrating T

cells. Therefore, this subtype of lymphoma may represent a candidate

for inhibiting the PD1–PD1-ligand axis.[44]

In a

phase 1, open-label, single agent dose-escalation study,

Nivolumab, an anti-PD1–blocking IgG4 antibody with higher affinity,

yielded a response rate of 40% in 10 patients with relapsed/refractory

FL, with a complete response rate of 10%, lending support to the

importance of immune surveillance in the control and progression of

this disease.[45]

Pidilizumab is

an IgG1 isotype anti-PD1 antibody with lower affinity than other

anti-PD-1 immune-checkpoint inhibitors. In 2014, the first results of a

single group, phase 2 trial of pidilizumab combined with rituximab in

relapsing follicular lymphoma were published. This combination showed a

high objective response (66%) and complete response (52%,) with a

median progression-free survival of 18・8 months (95% CI 14・7–not

reached), an improvement on the expected results of rituximab alone in

the same setting. No adverse events of grade 3-4 were reported.[46]

Although

the actual benefit of this combination has to be established in a

randomised study, these findings suggest that pidilizumab might enhance

antitumor immune responses. The investigators correlated baseline gene

expression signatures in tumor biopsy samples of 18 patients with the

outcome of anti-PD1 therapy. They showed that a prominent T-cell

activation signature or a signature of genes repressed in regulatory T

cells were significantly associated with prolonged progression-free

survival. Of major interest was the finding that a drug specifically

targeting the immune system (pidilizumab) could be combined with drugs

directly targeting the pathological cells (rituximab) to improve

results.

To date, several trials with other checkpoint inhibitors

such as ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 (NCT01592370), and pembrolizumab,

another PD-1 inhibitor, (NCT02446457), are ongoing.

Bispecific T-cell Engagers and CAR-T Cells

Combining the specific targeting of the FL neoplastic cells obtained

by mAb with the recruitment and activation of immune cells may

ultimately be the most efficient strategy to achieve the definitive

cure of FL.

A highly attractive approach is the application of the

bi-specific T-cell engaging (BiTE) antibody blinatumomab which targets

both CD19 and CD3 antigens. Although the development of this BiTE

antibody is currently focused on B-precursor acute lymphoblastic

leukemia, promising, early results were also obtained in B-cell

lymphomas, where single agent blinatumomab at the dose of 60 ug/m2/day achieved an ORR of 80% in heavily pretreated FL patients, although with significant neurotoxicity with encephalopathy.[47]

Expanding clinical experience with the use of these molecule has

reduced the important side effects initially observed. Moreover,

subcutaneous formulations of blinatumumab have been developed and are

currently being tested to allow its easier use in patients with

lymphoma.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells

have generated broad interest in oncology following a series of

dramatic clinical successes in patients with chemorefractory B cell

malignancies. CAR therapy now appears to be on the cusp of regulatory

approval as a cell-based immunotherapy.

Following a decade of

preclinical optimization, CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) therapy

has rapidly made a high impact in oncology. Within a few years, the CAR

field has progressed from reports of anecdotal responses in patients

with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

to achieving reproducible outcomes in hundreds of patients with B cell

malignancies, most strikingly in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

(B-ALL), including patients with chemotherapy-refractory disease.[48]

Indeed, the antitumor activity of anti-CD19 CAR was first reported in a

case of advanced follicular NHL, in which anti-CD19 CAR therapy

resulted in dramatic regression. Peripheral blood B-cells were absent

for at least 39 weeks after treatment, but no acute toxicities

occurred.[49]

This field is rapidly

expanding both in the molecular engineering of new and more active

products and in their clinical application in different hematological

malignancies, including cases of FL.[50]

Nevertheless, the reproducibility and feasibility of CAR-T cell therapy

on a scale broad enough to be offered to a large population of patients

with CD19-positive malignancies need to be adequately demonstrated in

more extensive studies.

The results of autologous CD19-targeted

second-generation CAR T cells treatment obtained so far in indolent NHL

patients have been recently updated.[51] Of 15

patients enrolled, eight achieved complete remissions (CRs), four

achieved partial remissions, one had stable lymphoma, and two were not

evaluable for response. CRs were obtained by four of seven evaluable

patients with chemotherapy-refractory DLBCL; three of these four CRs

are ongoing, with durations ranging from 9 to 22 months. Acute

toxicities including fever, hypotension, delirium, and other neurologic

toxicities occurred in some patients after infusion of anti-CD19 CAR T

cells; these toxicities resolved within three weeks after cell

infusion. One patient died suddenly as a result of an unknown cause 16

days after cell infusion. The most troublesome toxicities experienced

by patients were hypotension and neurologic toxicities. The mechanism

of these neurologic toxicities is not entirely known. Elevated levels

of interferon gamma and of interleukin-6 but not of tumor necrosis

factor-alfa were common. Importantly, all patients recovered completely

from their neurologic toxicities. Some of the neurologic toxicities

observed were similar to toxicities observed in other trials of

anti-CD19 CAR T cells and clinical trials of anti-CD19– and

anti-CD3–bispecific antibodies.

In conclusion, in the last few

years, several targeted drugs have shown activity in FL. Some of them

like lenalidomide, selected PI3k inhibitors, and several new anti CD-20

monoclonal antibodies are likely to enter the clinical arena soon.

Other compounds are still under clinical evaluation, like

BTK-inhibitors, anti-bcl-2, and immunotoxins, whereas highly promising

approaches, such as CART-cells and bispecific antibodies, need

additional investigations to define their activity/toxicity and their

best place in the treatment strategy for FL. All together they will

certainly further expand our therapeutic armamentarium for FL patients

including the highly refractory population that still has a dismal

prognosis and no therapeutic options.

However, we must highlight

that “chemo-free” treatments are not “toxicity-free,” which means that

despite a different safety profile from that of the standard

immunochemotherapy regimens, these new therapies continue to present

significant and still incompletely known toxicities. The major trials,

especially in the front-line setting and with combinations of different

agents, have a limited follow-up period and involve relatively small

patient populations. Thus, caution must be exercised in the

interpretation of their results and only time will tell if they will

ultimately replace our standard therapeutic approaches.

To

conclude, we believe that the real challenge in the near future will be

how to optimize and integrate in the clinical practice the results of

the many studies reported, with the goal of achieving the cure of FL

without compromising the quality of life of our patients. A further

challenge, whose discussion is beyond the scope of the present review,

will be how to optimize treatments also from an economic perspective.

Given the high costs of all the novel agents described, the

sustainability of every treatment program based on their use is likely

to become equally important as their efficacy.

References

[TOP]