Kalliopi Zachou, Pinelopi

Arvaniti, Nikolaos K. Gatselis, Kalliopi Azariadis, Georgia Papadamou,

Eirini Rigopoulou and George N. Dalekos

Department of Medicine and Research Laboratory of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece

Corresponding

author: George N. Dalekos, MD, PhD. Professor of Medicine. Head,

Department of Medicine and Research Laboratory of Internal Medicine.

University of Thessaly, School of Medicine. Biopolis, Larissa, 41110

Larissa, Greece. Tel: ++30-2410-682285; Fax: ++30-2410-671863. E-mail:

georgedalekos@gmail.com

Published: January 1, 2017

Received: August 14, 2016

Accepted: November 11, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017003 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.003

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background & objectives:

In the past, patients with haemoglobinopathies were at high risk of

acquiring hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to multiple transfusions before

HCV screening. In these patients, the coexistence of haemochromatosis

and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) often leads to more severe liver disease.

We assessed the HCV prevalence, clinical characteristics and outcome in

this setting with particular attention to the response to treatment

including therapies with the new direct acting antivirals (DAAs).

Methods: The medical records of 81 consecutive patients followed the last 15 years were reviewed retrospectively.

Results:

43/81 (53%) patients were anti-HCV positive including 31/43 (72.1%)

with CHC (HCV-RNA positive; age 25±7 years; 45.2% with genotype 1b;

19.4% cirrhotics; baseline ferritin 887 ng/ml; range: 81-10.820).

Thirty patients received IFN-based therapy with or without ribavirin

with sustained virological response (SVR) in 14/30 (46.7%). Eleven

patients (9 non-responders to IFN-based therapies, one in relapse and

one naïve) received treatment with DAAs (SVR: 100%). 3/11 patients

increased their transfusion needs while 1/11 reported mild arthralgias.

No drug-drug interactions between DAAs and chelation agents were

observed as attested by the stability of ferritin levels during

treatment.

Conclusions:

More than 1/3 of patients with haemoglobinopathies suffered from CHC.

Response rates to IFN-based treatment seem to be similar to other

patients with CHC, while most importantly, treatment with DAAs was

excellent and safe even in difficult to treat patients (most null

responders with severe fibrosis) suggesting that this group of HCV

patients should no longer be regarded as a difficult to treat.

|

Introduction

Hepatitis

C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes of chronic liver

disease worldwide. Indeed, the most recent estimates of disease burden

show an increase in seroprevalence over the last 15 years to 2.8%,

resulting in >185 million infections worldwide.[1,2]

In

the past, patients with haemoglobinopathies represented a population at

high risk of acquiring HCV as before 1992 there was no blood screening

for HCV. As a result, the prevalence of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) in

patients with thalassemia varies depending on the population studied

between 12% and 85%.[3]

As chelation therapy with

new drugs seems to prevent cardiac damage and improve survival, the

chronic liver disease has emerged as a critical clinical issue in this

setting. The ‘hit’ to the liver is at least dual: high frequency of

chronic viral infections, especially HCV, and secondary hemochromatosis

of the liver due to multiple transfusions and dyserythropoiesis.[4]

Furthermore, chronic hepatitis C (CHC) and iron overload were proved to

be independent risk factors for liver fibrosis progression and their

concomitant presence results in a striking increase of the risk.[5]

So, it is essential for patients with haemoglobinopathies to have a

multidisciplinary approach, in order to achieve both effective

chelation therapy and treatment of CHC, with a view to preventing liver

complications and improve morbidity and mortality.[3,4,6]

Clinical

care for patients with the HCV-related liver disease has improved

considerably during the last two decades, thanks to the enhanced

understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease, and the

therapeutic advances.[7] Until 2011, interferon-α

(IFN-α) with or without ribavirin was the approved treatment for

patients with thalassemia, resulting in sustained virological response

(SVR) rates of 40-60%.[8-10] The recent license of

Direct Acting Antivirals (DAAs) opened new venues in the treatment of

CHC regarding extremely high SVR rates and better compliance due to

their oral route of administration and the rarity of significant side

effects.[7] In addition, the new treatment modalities

for HCV infection permit avoiding ribavirin use in the majority of

cases, which is well-known to increase the transfusion needs by a

median of 30–40% as well as side effects in these patients.[9,11-17] The recent EASL treatment recommendations on hepatitis C,[7]

suggest that patients with haemoglobinopathies should be treated with

an IFN-free regimen, without ribavirin. However, patients with

haemoglobinopathies and CHC have been excluded from the major clinical

trials that led to the approval of DAAs. Indeed, so far, only some case

reports have been published showing favourable results after DAAs

administration in CHC patients with concurrent haemoglobinopathies.[18,19]

Hence, at present, no experience is available regarding the safety and

efficacy of DAAs in this population which is traditionally considered

difficult to treat, because of the coexistence of liver

hemochromatosis, the more advanced liver disease and the usual

nonresponse or relapse to previous IFN-based therapies.

Accordingly, the aims of our study were:

1°

to assess the prevalence of CHC in patients with haemoglobinopathies in

Central Greece a region with low anti-HCV prevalence (0.34%) in the

general population;[20]

2° to report the

clinical characteristics and the outcome in this setting giving

particular attention to the response to treatment after utilizing the

new DAAs and a strong emphasis on the safety and efficacy of use in

this specific population.

Patients and Methods

The

medical records of 81 consecutive patients with haemoglobinopathies (70

with β-thalassemia major and 11 with sickle cell anaemia/β-thalassemia)

followed by our Department between 2000 and 2015 were retrospectively

analysed. For patients who had received IFN-based treatment, sustained

virological response (SVR) was defined according to the European

Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) clinical practice

guidelines published in 2011 (serum HCV-RNA<50 IU/ml 24 weeks after

treatment withdrawal).[8] For patients who received

DAAs, SVR was defined according to the EASL clinical practice

guidelines published in 2015 (undetectable serum HCV-RNA 12 weeks after

stopping treatment).[7]

Anti-HCV was determined

using a second- or third-generation enzyme immunoassay at least twice

within six months while active virus replication was defined by the

detection of HCV-RNA using a sensitive commercially available

quantitative real-time PCR kit (COBAS Taqman HCV Test; cut-off of

detection: 25 IU/ml).

The histological evaluation was assessed using the Knodell histologic/activity index score.[21] According to previous publications of our group,[22-24]

for statistical reasons patients were divided into two groups according

to inflammation: minimal-mild (score:0-8) and moderate-severe

(score:9-18) and according to fibrosis: none-mild-moderate (score:0-2)

and severe fibrosis-cirrhosis (score:3-4).

In addition, fibrosis

was assessed in 11 patients who received DAAs by transient elastography

(FibroScan device powered by VCTE Echosens equipped with the standard M

probe). Liver stiffness measurements (LMS) were expressed as median

(kPa) of all valid measurements with associated interquartile range

(IQR) and success rate. LSM was considered valid if there were ten

successful acquisitions and an IQR/LSM <0.3. Patients were divided

into four groups; F0-F1, F1-F2, F2-F3 and F3-F4 according to Metavir

score.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Thessaly University, Medical School.

Statistical analysis: Results are expressed as median (range) and mean ± SD where appropriate. Data were analysed by Mann-Whitney U-test (MWU), x2 (two-by-two with Yate’s correction) and Fisher’s exact test. Two-sided p

values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

95%CI were calculated with the Wilson procedure with a correction for

continuity. Results

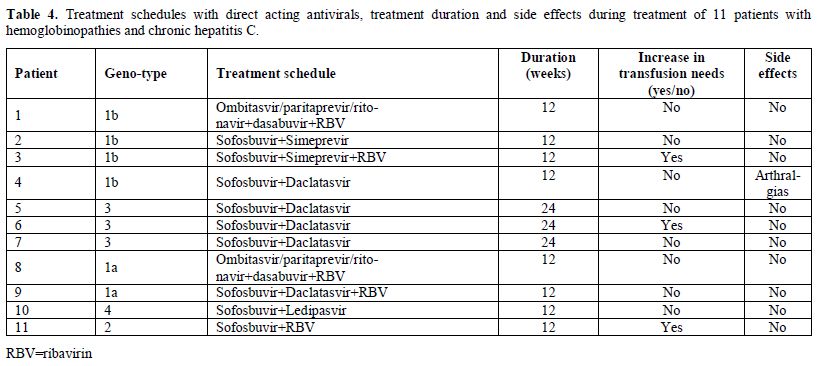

Forty-three

out of 81 patients (53%; 95%CI: 42-63.8%) tested anti-HCV positive.

Thirty-one patients had CHC (31/81; 38%; 95%CI: 27.4-48.6%) as they

were HCV-RNA positive. The baseline epidemiological, clinical,

laboratory and histologic characteristics of CHC patients with

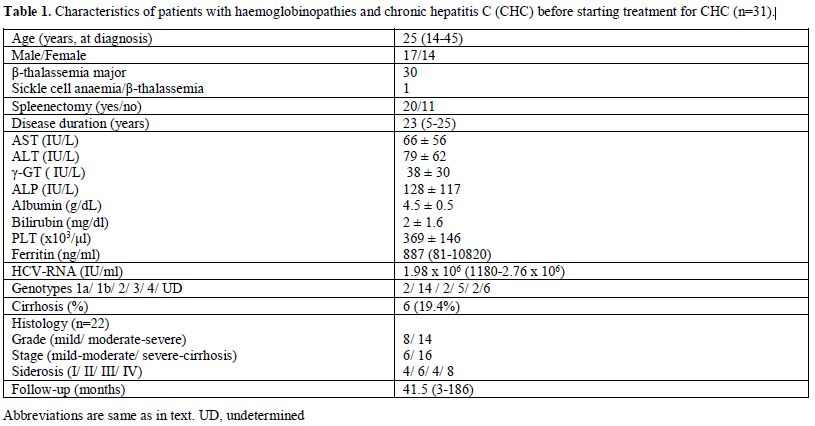

haemoglobinopathies are shown in Table 1.

All patients but one with sickle cell anaemia/β-thalassemia, were

receiving chelation therapy to avoid iron overload, however, ferritin

levels varied (Table 1). Liver

histology before starting therapy was available in 22 patients. In

total, clinical and/or histological evidence of cirrhosis had 6/31

(19.4%; 95%CI: 5-33%) patients.

|

Table

1. Characteristics of patients with haemoglobinopathies and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) before starting treatment for CHC (n=31). |

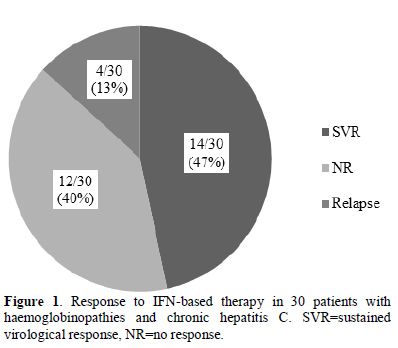

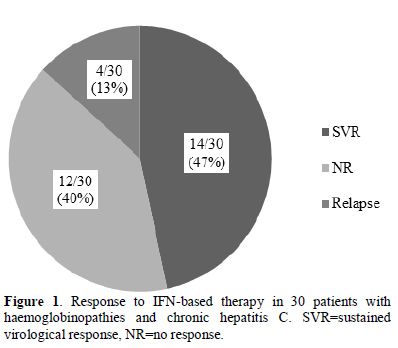

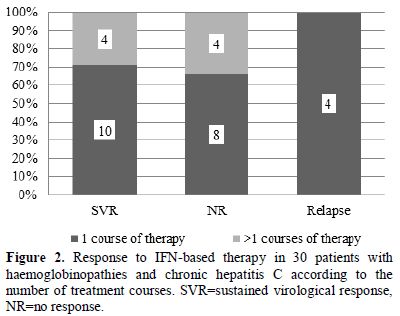

Thirty out of 31 CHC

patients received IFN-based therapy with or without ribavirin. The SVR

rate independently of HCV-genotype, in IFN-based treated patients, was

46.7% (14/30; 95%CI: 29-64%) (Figure 1).

In fact, 22 patients had received one treatment course with IFN-based

therapy, while the remaining (8/30; 26.6%; 95%CI: 11-42%) had received

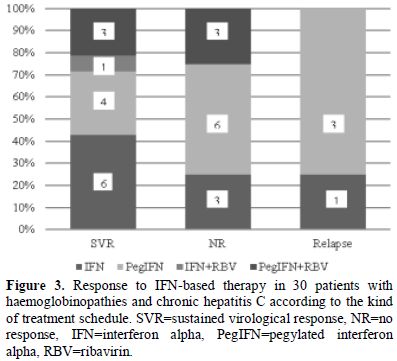

more than one course. In Figure 2, the type of treatment response to IFN-based therapy in respect to the number of treatment courses is shown. In Figure 3, the type of treatment response according to the IFN-based treatment schedule is also shown.

|

Figure 1. Response to IFN-based therapy in

30 patients with haemoglobinopathies and chronic hepatitis C.

SVR=sustained virological response, NR=no response. |

|

Figure 2. Response to

IFN-based therapy in 30 patients with haemoglobinopathies and chronic

hepatitis C according to the number of treatment courses. SVR=sustained

virological response, NR=no response. |

|

Figure 3. Response to IFN-based therapy in

30 patients with haemoglobinopathies and chronic hepatitis C according

to the kind of treatment schedule. SVR=sustained virological response,

NR=no response, IFN=interferon alpha, PegIFN=pegylated interferon

alpha, RBV=ribavirin. |

The SVR rate

in patients who received monotherapy with IFN or PegIFN (10/23; 43%;

95%CI: 23-63%) did not significantly differ compared to that observed

in patients who received combination therapy with ribavirin (4/7; 57%;

95%CI: 20-94%). Two out of 7 patients who received ribavirin increased

their transfusion needs. In total, 4/30 (13.3%; 95%CI: 1-25%) developed

neutropenia during treatment but treatment was not discontinued while

one patient presented anxiety and severe myalgias which led to

treatment discontinuation.

Regarding outcome (except three

patients who were lost to follow-up), 6 out of 22 (27%; 95%CI: 8-45%)

patients who were not cirrhotic at initial presentation, developed

cirrhosis. Two out of 6 patients who developed cirrhosis achieved an

SVR with IFN-based therapies whereas 10/16 patients, who did not

develop cirrhosis achieved SVR during follow-up (p>0.05). Of note,

no patient died during the follow-up of the study.

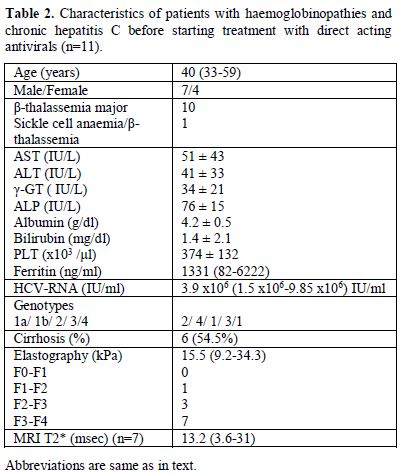

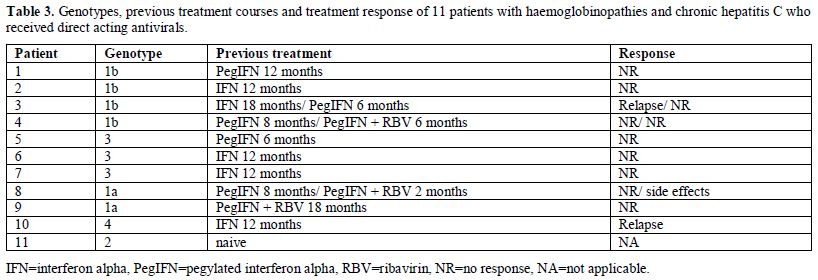

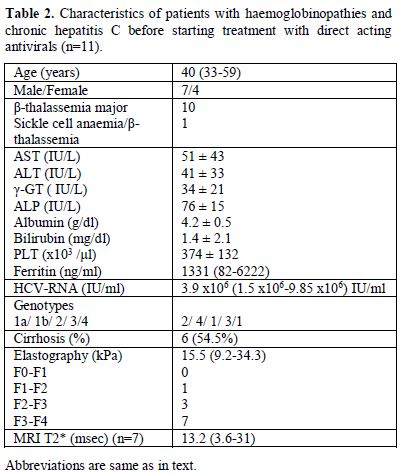

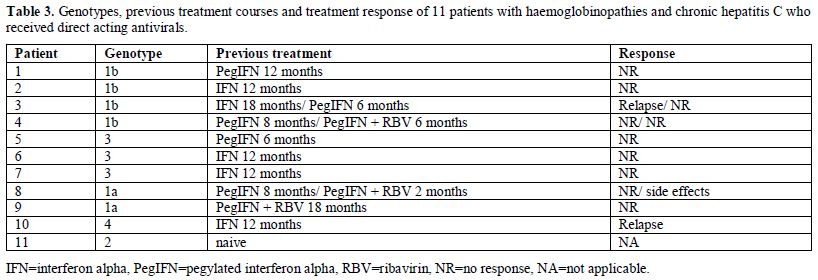

Eleven

patients (9 non-responders to previous treatment with IFN-based

therapies, one in relapse and one naïve patient) received treatment

with DAAs according to the recent EASL guidelines[7] (Tables 2 and 3). The baseline epidemiological, clinical, laboratory and histologic characteristics of these 11 patients are shown in Table 2. Seven patients had MRI T2* measurements during the last six months and had mild (n=5) to moderate liver hemochromatosis (n=2; Table 2).

Regarding chelation therapy, three patients were receiving

deferoxamine, two deferasirox, one deferiprone and four a combination

of deferoxamine with deferiprone. The estimation of liver disease stage

was based on transient elastography and 7/11 (63.6%; 95%CI: 35-92%)

patients had severe fibrosis (F3-F4) (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with

haemoglobinopathies and chronic hepatitis C before starting treatment

with direct acting antivirals (n=11). |

|

Table 3. Genotypes, previous treatment

courses and treatment response of 11 patients with haemoglobinopathies

and chronic hepatitis C who received direct acting antivirals. |

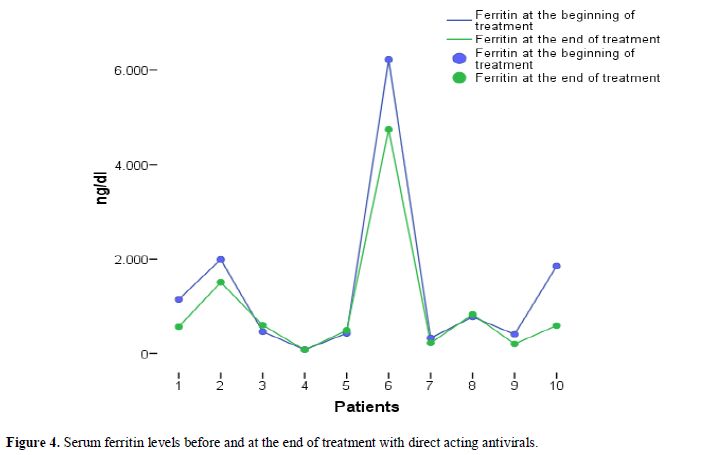

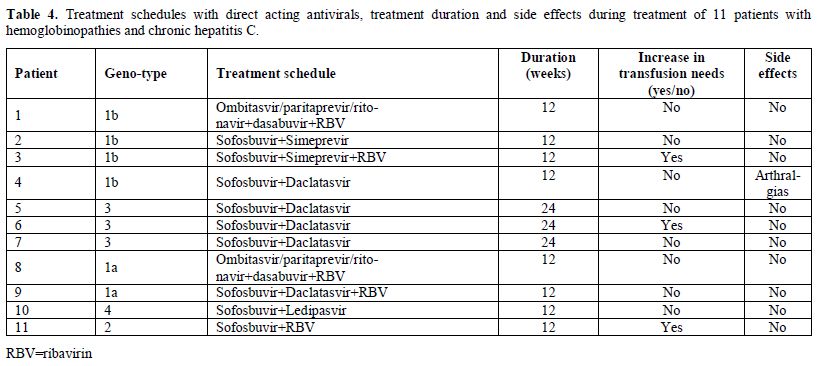

The treatment schedules with DAAs are shown in Table 4.

Regarding safety, only one patient mentioned arthralgias which,

however, did not lead to treatment discontinuation. Three patients

increased the transfusion needs (two of them were receiving ribavirin).

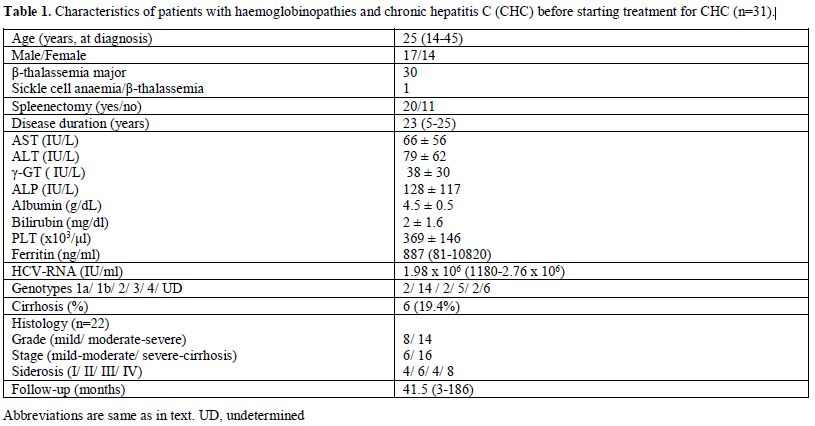

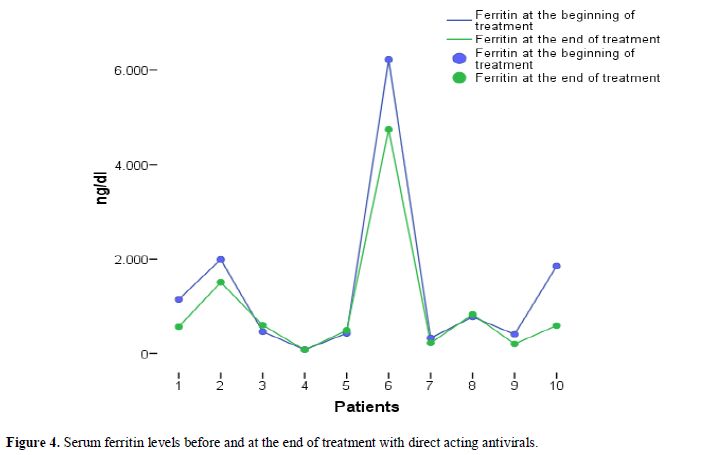

As far as ferritin levels are concerned, there was no significant

elevation during treatment with DAAs (Figure 4). All 11 patients treated with DAAs achieved SVR at week 12 post treatment.

|

Table 4. Treatment schedules with direct

acting antivirals, treatment duration and side effects during treatment

of 11 patients with hemoglobinopathies and chronic hepatitis C. |

|

Figure 4. Serum ferritin levels before and at the end of treatment with direct acting antivirals. |

Discussion

The

current study assessed the prevalence of anti-HCV positivity and that

of CHC among patients with haemoglobinopathies, the characteristics of

the patients with CHC and haemoglobinopathies, and their response to

treatment with emphasis to the preliminary results of the treatment

responses to DAAs in this patient group. The following three major

points have risen:

a) the prevalence of anti-HCV and CHC in patients with haemoglobinopathies is still increased;

b)

HCV infection is diagnosed in young age, however 20% of the patients

had already cirrhosis before starting treatment and almost 50% were

infected with HCV genotype 1b;

c) the response rates to IFN-based

therapies were the same as in other patient groups, while most

importantly, treatment with DAAs was very effective (SVR 100%) and safe

even in difficult to treat HCV patients (most null responders with

severe fibrosis/cirrhosis).

In our retrospective study, we found a

prevalence anti-HCV positivity of 53% in patients with

haemoglobinopathies, while more than one-third of the patients (38%)

had CHC. This datum is in accordance with previous studies from Greece[25,26] and other European countries.[27]

As far as HCV genotype is concerned, almost half of our patients were

infected with genotype 1b, which is the most prevalent genotype among

multitransfused patients [3,28]. In

addition, nearly 20% of the patients had cirrhosis before treatment

initiation which is in accordance with previous studies in patients

with CHC and thalassemia,[3,26,29]

while the rate of progression of liver disease to cirrhosis was 27%

with a median disease duration of 23 years. The progression to

cirrhosis seems to be higher than that expected in other patients with

CHC without haemoglobinopathies.[30,31] Of note, the

achievement of SVR did not influence the progression to cirrhosis which

is rather dependent on the degree of liver iron overload.[29]

In

general, the SVR rate among patients treated with IFN-based therapies

(47%) was similar to previous reports in this population,[3,14,15] while the SVR rate among those who received IFN/Peg-IFN monotherapy was 43%, similar as in past studies.[9,12,16,17]

In a small subset of patients (n=7) who received IFN/PegIFN in

combination with ribavirin, the SVR rate was 57%, while only the

minority of them increased their transfusion needs.[3,11,13,32]

However, haemolysis was reversible after drug discontinuation, and no

significant iron overload worsening was noticed. According to our

study, the SVR rates both in patients treated with IFN monotherapy and

those treated with IFN in combination with ribavirin were similar to

other CHC patients.[33-35]

The main and most

important finding of our study, however, was the high SVR rate (100%)

achieved among HCV treatment-experienced difficult (null-responders)

patients with haemoglobinopathies who were treated with DAAs. All

patients received the appropriate treatment according to the HCV

genotype and fibrosis severity, but they considered to be difficult to

treat population, as all but one, were treatment-experienced and had

advanced liver fibrosis (stage F3-4 according to liver elastography).

Even though the number of patients was small to drawn safe conclusions,

this is one of the first studies showing quite convincingly that the

SVR rate to DAAs in multitransfused difficult-to-treat HCV patients is

similar to that observed in nonmulti-transfused naïve individuals with

CHC.[36-40]

As far as safety is concerned, none

of the 11 patients who received DAAs withdrew treatment because of side

effects while transfusion rate was elevated in 3 patients, 2 of whom

also received ribavirin. However, no significant elevation of serum

ferritin levels was observed during and after treatment. In addition,

all patients were under treatment with chelation agents. There are no

data so far about the drug-drug interactions of chelation agents and

DAAs. Although the present study was not designed to investigate

pharmacodynamics, chelation treatment does not seem to affect treatment

with DAAs.

Conclusion

More

than one-third of patients with haemoglobinopathies are still

chronically infected with CHC. Patients with haemoglobinopathies and

HCV infection seem to have similar SVR rates after IFN-based treatment

compared to other CHC patients. However, the most important and

fascinating finding of our study was the excellent virological response

rates (SVR 100%) after treatment with DAAs even in difficult to treat

HCV patients (null responders with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis).

Side-effects related to DAAs treatment were minimal, while transfusions

rate seems to increase in some patients treated with ribavirin, without

however an elevation of ferritin levels. Therefore, our results further

support the statement of EASL and AASLD guidelines that IFN-α free

treatment with DAAs should be considered as first-line therapy in

treatment-naïve or treatment experienced patients with or without

cirrhosis due to CHC and concurrent haemoglobinopathies. Finally,

chelation therapy does not seem to affect treatment with DAAs, however,

current literature lacks sufficient evidence to give definitive support

to these preliminary results. Thus, larger studies are warranted to

ensure the safety and efficacy of DAAs in patients with

haemoglobinopathies and CHC. However, our initial results strongly

suggest that this group of HCV patients should no longer be regarded as

a “difficult” to treat when the new DAAs are used. Our study support

the need to make available the DAAs also for south-east Mediterranean

and Asian countries considering the large number of patients with

haemoglobinopathies and HCV in these areas.[41-45]

References

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman

AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new

estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology.

2013;57:1333–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26141 PMid:23172780

- Papatheodoridis

G, Thomas HC, Golna C, Bernardi M, Carballo M, Cornberg M, Dalekos G,

Degertekin B, Dourakis S, Flisiak R, Goldberg D, Gore C, Goulis I,

Hadziyannis S, Kalamitsis G, Kanavos P, Kautz A, Koskinas I, Leite BR,

Malliori M, Manolakopoulos S, Maticic M, Papaevangelou V, Pirona A,

Prati D, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Reic T, Robaeys G, Schatz E, Souliotis K,

Tountas Y, Wiktor S, Wilson D, Yfantopoulos J, Hatzakis A. Addressing

barriers to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis B and

C in the face of persisting fiscal constraints in Europe: report from a

high level conference. J Viral Hepat 2016;23 (Suppl 1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12493 PMid:26809941

- Di

Marco V, Capra M, Angelucci E, Borgna-Pignatti C, Telfer P, Harmatz P,

Kattamis A, Prossamariti L, Filosa A, Rund D, Gamberini MR, Cianciulli

P, De Montalembert M, Gagliardotto F, Foster G, Grangè JD, Cassarà F,

Iacono A, Cappellini MD, Brittenham GM, Prati D, Pietrangelo A, Craxì

A, Maggio A; Italian Society for the Study of Thalassemia and

Haemoglobinopathies; Italian Association for the Study of the Liver..

Management of chronic viral hepatitis in patients with thalassemia:

recommendations from an international panel. Blood. 2010;116:2875-83. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-11-248724 PMid:20551378

- Hershko C. Pathogenesis and management of iron toxicity in thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1202:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05544.x PMid:20712765

- Angelucci

E, Muretto P, Nicolucci A, Baronciani D, Erer B, Gaziev J, Ripalti M,

Sodani P, Tomassoni S, Visani G, Lucarelli G. Effects of iron overload

and hepatitis C virus positivity in determining progression of liver

fibrosis in thalassemia following bone marrow transplantation. Blood.

2002;100:17-21. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V100.1.17 PMid:12070002

- Di

Marco V, Capra M, Gagliardotto F, Borsellino Z, Cabibi D, Barbaria F,

Ferraro D, Cuccia L, Ruffo GB, Bronte F, Di Stefano R, Almasio PL,

Craxì A. Liver disease in chelated transfusiondependent thalassemics:

the role of iron overload and chronic hepatitis C. Haematologica.

2008;93:1243-6. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.12554 PMid:18556410

- EASL recommendations on treatment of Hepatitis C 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;63:199-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025 PMid:25911336

- European

Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice

Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol.

2011;55:245–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.023 PMid:21371579

- Donohue

SM, Wonke B, Hoffbrand AV, Reittie J, Ganeshaguru K, Scheuer PJ, Brown

D, Dusheiko G. Alpha interferon in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C

infection in thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol. 1993;83:491-497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb04676.x PMid:8387324

- Hussein

NR, Tunjel I, Basharat Z, Taha A, Irving W. The treatment of HCV in

patients with haemoglobinopathy in Kurdistan Region, Iraq: a single

centre experience. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:1634-40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815003064 PMid:27125573

- Telfer

PT, Garson JA, Whitby K, et al. Combination therapy with interferon

alpha and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in

thalassaemic patients. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:850-855. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2953112.x PMid:9326177

- Di

Marco V, Lo Iacono O, Almasio P, Ciaccio C, Capra M, Rizzo M, Malizia

R, Maggio A, Fabiano C, Barbaria F, Craxi A. Long-term efficacy of

alpha interferon in beta-thalassemics with chronic hepatitis C. Blood.

1997;90: 2207-12. PMid:9310471

- Li

CK, Chan PK, Ling SC, Ha SY. Interferon and ribavirin as frontline

treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection in thalassaemia major. Br J

Haematol. 2002;117:755-8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03491.x

- Butensky

E, Pakbaz Z, Foote D, Walters MC, Vichinsky EP, Harmatz P. Treatment of

hepatitis C virus infection in thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005;

1054: 290-299. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1345.038 PMid:16339677

- Alavian

SM, Tabatabaei SV. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in polytransfused

thalassaemic patients: a meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:236-244.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01170.x PMid:19638104

- Vafiadis

I, Trilianos P, Vlachogiannakos J, Karagiorga M, Hatziliami A,

Voskaridou E, Ladas SD. Efficacy and safety of interferon-based therapy

in the treatment of adult thalassemic patients with chronic hepatitis

C: a 12 years audit. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:532-8. PMid:23813130

- Kalafateli

M, Kourakli A, Gatselis N, Lambropoulou P, Thomopoulos K, Tsamandas A,

Christofidou M, Zachou K, Jelastopoulou E, Nikolopoulou V,Symeonidis A,

Dalekos GN, Lambropoulou-Karatza C, Triantos C. Efficacy of interferon

a-2b monotherapy in b-thalassemics with chronic hepatitis C. J

Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:189-96. PMid:26114179

- Papadopoulos

N, Deutsch M, Georgalas A, Poulakidas H, Karnesis L. Simeprevir and

sofosbuvir combination treatment in a patient with HCV cirrhosis and

HbS beta 0-thalassemia: Efficacy and safety despite baseline

hyperbilirubinemia. Case Rep Hematol. 2016;2016:7635128. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7635128

- Hussein

NR. Sofosbuvir-containing regimen for the treatment of hepatitis C

virus in a patient with sickle-thalassemia: The first case report. Int

J Infect. 2016 (In press), doi: 10.17795/iji-38077. https://doi.org/10.17795/iji-38077

- Gatselis

NK, Rigopoulou E, Stefos A, Kardasi M, Dalekos GN. Risk factors

associated with HCV infection in semi-rural areas of central Greece.

Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18:48-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.008 PMid:17223043

- Knodell

RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW,

Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system

for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active

hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431-35. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840010511 PMid:7308988

- Gatselis

NK, Zachou K, Norman GL, Tzellas G, Speletas M, Gabeta S, Germenis A,

Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN. IgA antibodies against deamidated gliadin

peptides in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2012;

413:1683-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2012.05.015 PMid:22643316

- Kaffe

ET, Rigopoulou EI, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN, Moulas AN. Oxidative

stress and antioxidant status in patients with autoimmune liver

diseases. Redox Rep 2015;20:33-41. https://doi.org/10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000101 PMid:25117650

- Norman

GL, Gatselis NK, Shums Z, Liaskos C, Bogdanos DP, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos

GN. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein: A novel non-invasive marker

for assessing cirrhosis and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J

Hepatol 2015;7:1875-83. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i14.1875 PMid:26207169 PMCid:PMC4506945

- Kountouras

D, Tsagarakis NJ, Fatourou E, Dalagiorgos E, Chrysanthos N, Berdoussi

H, Vgontza N, Karagiorga M, Lagiandreou A, Kaligeros K, Voskaridou

E,Roussou P, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Koskinas J. Liver disease in adult

transfusion dependent beta-thalassaemia patients: investigating the

role of iron overload and chronic HCV infection. Liver Int

2013;33:420-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12095 PMid:23402611

- Triantos

C, Kourakli A, Kalafateli M, Giannakopoulou D, Koukias N, Thomopoulos

K, Lampropoulou P, Bartzavali C, Fragopanagou H, Kagadis GC,

Christofidou M, Tsamandas A, Nikolopoulou V, Karakantza M,

Labropoulou-Karatza C. Hepatitis C in patients with ß-thalassemia

major. A single-centre experience. Ann Hematol 2013;92:739-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1692-6 PMid:23412560

- Prati

D, Poli F, Farma E, Picone A, Porta E, Mattei C, Zanella A, Scalamogna

A, Gamba A, Gronda E, Faggian G, Livi U, Puricelli C, Viganò M, Sirchia

G. A multicenter prospective study on the risk of acquiring liver

disease in anti-hepatitis C virus negative patients affected from

homozygous beta-thalassemia. Blood. 1998;92:3460-64. PMid:9787188

- Christofidou

M, Lambropoulou-Karatza C, Dimitracopoulos G, Spiliopoulou I.

Distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in viremic patients with

beta-thalassemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:728-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100960000342 PMid:11057513

- Lai

ME, Origa R, Daniou F, Leoni GB, Vacquer S, Anni F, Corrias C, Farci P,

Conqiu G, Galanello R. Natural history of hepatitis C in thalassemia

major: a long-term prospective study. Eur J Hematol. 2013;90:501-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12086 PMid:23414443

- Thein

HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis

progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a

meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48:418-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22375 PMid:18563841

- Lingala S, Ghany MG. Natural history of hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:717-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2015.07.003 PMid:26600216

- Sherker

AH, Senosier M, Kermack D. Treatment of transfusion-dependent

thalassemic patients infected with hepatitis C virus with interferon

alpha-2b and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2003;37:223. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50037 PMid:12500209

- Poynard

T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, NiederauC, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote

J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C, Albrecht J. Randomised trial of interferon

alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon

alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection

with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy

Group (IHIT). Lancet. 1998;352:1426-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4

- Fried

MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Haussinger

D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D, Craxi A, Lin A, Hoffman J, Yu J.

Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus

infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020047 PMid:12324553

- Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Cornberg M. Treating viral hepatitis C: efficacy, side effects, and complications Gut. 2006;55:1350–59. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.076646 PMid:16905701 PMCid:PMC1860034

- Sulkowski

MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M, Reddy KR, Hassanein T, Jacobson I,

Lawitz E, Lok AS, Hinestrosa F, Thuluvath PJ, Schwartz H, Nelson

DR,Everson GT, Eley T, Wind-Rotolo M, Huang SP, Gao M, Hernandez D,

McPhee F, Sherman D, Hindes R, Symonds W, Pasquinelli C, Grasela DM;

AI444040 Study Group. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously

treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med.

2014;370:211–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306218 PMid:24428467

- Afdhal

N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, Nahass R, Ghalib

R, Gitlin N, Herring R, Lalezari J, Younes ZH, Pockros PJ, Di Bisceglie

AM, Arora S, Subramanian GM, Zhu Y, Dvory-Sobol H, Yang JC,Pang PS,

Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Muir AJ, Sulkowski M, Kwo P; ION-2

Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV

genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1483–93. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1316366 PMid:24725238

- Kowdley

KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Rossaro L, Bernstein DE, Lawitz E, Shiffman

ML, Schiff E, Ghalib R, Ryan M, Rustgi V, Chojkier M, Herring R, Di

Bisceglie AM, Pockros PJ, Subramanian GM, An D, Svarovskaia E, Hyland

RH, Pang PS, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Muir AJ, Pound D, Fried MW;

ION-3 Investigators.. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for

chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1879–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402355 PMid:24720702

- Feld

JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, Sigal S, Nelson DR, Crawford D, Weiland O,

Aguilar H, Xiong J, Pilot-Matias T, DaSilva-Tillmann B, Larsen L,

Podsadecki T,Bernstein B.. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir

and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1594–1603. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1315722 PMid:24720703

- Ferenci

P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J, Cohen D, Luo Y, Cooper C, Tam E, Marinho

RT, Tsai N, Nyberg A, Box TD, Younes Z, Enayati P, Green S, Baruch

Y,Bhandari BR, Caruntu FA, Sepe T, Chulanov V, Janczewska E, Rizzardini

G, Gervain J, Planas R, Moreno C, Hassanein T, Xie W, King M,

Podsadecki T, Reddy KR; PEARL-III Study; PEARL-IV Study..

ABT-450/rombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N

Engl J Med. 2014;370:1983–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402338 PMid:24795200

- Din

G, Malik S, Ali I, Ahmed S, Dasti JI. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus

infection among thalassemia patients: a perspective from a multi-ethnic

population of Pakistan. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7S1:S127-33.

- Rafiei

A, Darzyani AM, Taheri S, Haghshenas MR, Hosseinian A, Makhlough A.

Genetic diversity of HCV among various high risk populations (IDAs,

thalassemia, hemophilia, HD patients) in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med.

2013;6:556-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60096-6

- Shah

N, Mishra A, Chauhan D, Vora C, Shah NR. Study on effectiveness of

transfusion program in thalassemia major patients receiving multiple

blood transfusions at a transfusion centre in Western India. 4. Asian J

Transfus Sci. 2010;4:94-8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6247.67029 PMid:20859507 PMCid:PMC2937304

- Yazaji

W., Habbal W., Monem F. Seropositivity of hepatitis b and c among

Syrian multi-transfused patients. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016,

8(1): e2016046, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2016.046

- Hussein

E. Evaluation of infectious disease markers in multitransfused Egyptian

children with thalassemia. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014 Winter;44(1):62-6

PMid:24695476

[TOP]