Shahrzad Zonoozi1, Maria Barnard1, Emma Prescott2, Romilla Jones1, Farrukh T Shah2 and Ploutarchos Tzoulis1

1 Department of Diabetes, Whittington Hospital, Magdala Avenue, London, N19 5NF

2 Department of Haematology, Whittington Hospital, Magdala Avenue, London, N19 5NF

Corresponding

author: Ploutarchos Tzoulis, Department of Diabetes, Whittington Hospital, Magdala Avenue, London, N19 5NF. E-mail:

ptzoulis@yahoo.co.uk

Published: January 1, 2017

Received: October 3, 2016

Accepted: December 12, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017004 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.004

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Sitagliptin,

a modern antidiabetic agent which is weight neutral and associated with

low rate of hypoglycaemias, is being increasingly used in type 2

diabetes mellitus (DM). However, there is a paucity of data about its

efficacy and safety in beta-thalassaemia major (β-TM).

This

retrospective case series of five patients (mean age of 45 years) is

the first study evaluating the use of sitagliptin in patients with β-TM

and DM.

Four patients responded well to sitagliptin, as evidenced

by a decrease in fructosamine by 77 and 96µmol/L (equivalent reduction

in HbA1c of 1.5% and 1.9%) observed in two patients and reduction in

the frequency of hypoglycaemia without worsening glycaemic control in

two others. One patient did not respond to sitagliptin. No patients

reported significant side effects.

This study provides evidence

that sitagliptin may be considered, with caution, for use in patients

with β-TM and DM, under the close monitoring of a Diabetologist.

|

Introduction

The

aetiology of diabetes mellitus (DM) in patients with β-TM is

multifactorial. It has been predominantly attributed to

transfusion-related pancreatic iron overload resulting in destruction

of insulin secreting β cells of the pancreas and liver haemosiderosis

leading to insulin resistance.[1] Other factors such

as hepatitis C viral infection, autoimmunity, family history of DM and

genetic factors also play an important role.[2] As

life expectancy in patients with β-TM has risen substantially, optimal

glycaemic control is becoming extremely important in order to reduce

the risk of diabetic complications.

Sulfonylureas, traditionally

considered second line glucose-lowering agents after metformin, are

associated with a poor side-effect profile, including high risk of

hypoglycaemia and weight gain. For these reasons, the 2015 position

statement for type 2 DM recommends considering the use of dipeptidyl

peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors or gliptins as second line agents when

the first line agent, metformin, has not achieved optimal glycaemic

control.[3] The most popular drug in this drug class,

sitagliptin, inhibits DPP-4, the key enzyme which inactivates glucagon

like peptide 1 (GLP-1),[4] leading to increased levels

of GLP-1 in the plasma. GLP-1 is a gut hormone which increases insulin

secretion and suppresses glucagon secretion in a glucose-dependent

manner. DPP-4 inhibitors have similar glucose-lowering efficacy as

sulfonylureas, whilst associated with lower risk of hypoglycaemia and

no weight gain.[5] In addition, some studies have

suggested that sitagliptin may have greater durability of glucose

control and better maintenance of beta-cell function in comparison with

sulfonylureas.[6]

In patients with thalassaemia

and DM there has been little to no published data supporting the

efficacy of modern oral antidiabetic agents such as sitagliptin. The

aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of

sitagliptin in patients with β-TM and DM in a Specialist Thalassaemia

Centre in the UK.

Methods

Our

study is a retrospective case series of patients with β-TM and DM at

our institution treated with sitagliptin. All the participants attended

the Joint Diabetes Thalassaemia Clinic at our Specialised Thalassaemia

Centre serving the largest cohort of patients with thalassaemia in the

UK.

There were no pre-specified criteria for the use of

sitagliptin. For example, markers of pancreatic β-cell function, such

as serum C-peptide, and of insulin resistance, such as homoeostasis

model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), were not evaluated

prior to treatment initiation. They were not regarded as essential

since sitagliptin is effective as an add-on glucose-lowering therapy

even in patients with insulin deficiency by suppressing glucagon

secretion in a glucose-dependent manner.[7]

Retrospective

case notes and biochemical results review was performed in order to

collect data on: demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnic

origin), duration of diabetes, smoking status, weight, antidiabetic

treatment history, fructosamine, blood pressure, lipid profile, liver

function tests and ferritin on a 6-monthly basis starting from the time

point of sitagliptin initiation until most recent review or its

discontinuation.

Since glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) can be

unreliable in patients with β-TM due to regular transfusions,

fructosamine levels were regularly monitored as a surrogate marker of

glycaemic control in the preceding 2-3 weeks.[8]

Fructosamine was measured in the serum using a Roche Modular P800

system. A fructosamine level of 285 µmol/L was considered as being

equivalent to HbA1c of 6.5% with every additional 50 µmol/L of

fructosamine being calculated as equivalent to a rise of 1% in HbA1c.[9] Fructosamine and ferritin values were calculated as a mean of 2 or 3 results around the time point of interest.

Written informed consent was obtained from all five patients for publication of this case series. Results

Amongst

36 patients with β-TM and DM at our institution, five patients (4

females, 1 male), all with strong family history of diabetes and aged

between 44 and 50 years, were commenced on sitagliptin at a dose of 100

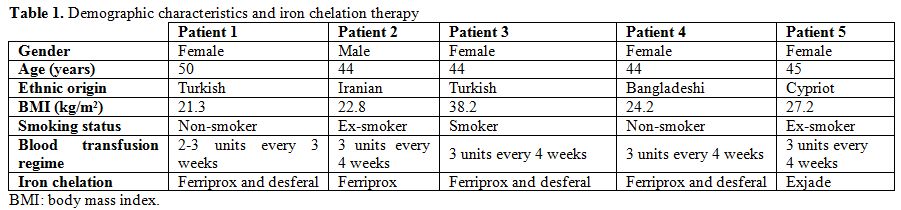

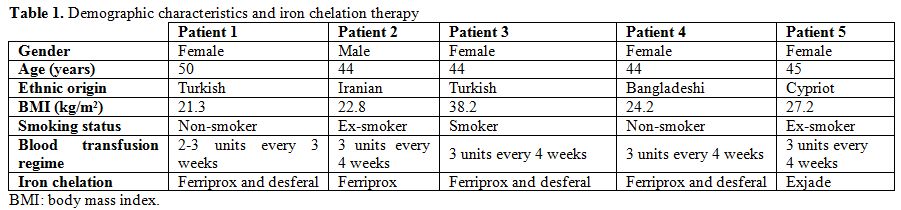

mg once daily, as shown in Table 1.

|

Table

1. Demographic characteristics and iron chelation therapy |

Sitagliptin was used

as second line agent in one patient, as add-on to metformin. Among the

other four patients on metformin and gliclazide combination therapy,

sitagliptin was added as 3rd line agent in two cases with poor glycaemic control, while it replaced gliclazide in two cases with frequent hypoglycaemias.

Review

of lipid profile and blood pressure during the time period of

sitagliptin treatment did not demonstrate any significant changes.

Patient 1.

A 50-year-old female with inadequate glycaemic control despite

lifestyle modification and metformin monotherapy was started on

sitagliptin. Fructosamine levels decreased from 340µmol/L to 323µmol/L

at 6 months and 263µmol/L at 12 months (equivalent reduction in HbA1c

of 0.3% and 1.2% respectively). Her weight increased by 1kg.

Patient 2.

Sitagliptin replaced gliclazide in a 44-year-old male who had poor

glycaemic control and frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia on dual

combination therapy with metformin and gliclazide. Fructosamine levels

initially decreased from 417µmol/L to 337µmol/L at 6 months (equivalent

reduction in HbA1c of 1.6%), but then increased to 353µmol/L at 12

months (equivalent increase in HbA1c of 0.3%). Around this time point,

gliclazide was reintroduced, resulting in fructosamine decrease to

343µmol/L at 24 months (equivalent HbA1c decrease of 0.2%). Episodes of

hypoglycaemia were eliminated, while weight remained stable for the

first 2 years, followed by an increase by 4kg in the final 6 months

when gliclazide was reintroduced.

Patient 3.

This 44-year-old female had frequent hypoglycaemias on dual combination

therapy of metformin and gliclazide. For this reason, gliclazide was

replaced with sitagliptin which resulted in an increase of fructosamine

levels from 246µmol/L to 333µmol/L at 6 months (equivalent 1.7%

increase in HbA1c). In light of poor response, sitagliptin was

withdrawn and substituted by gliclazide.

Patient 4.

This 44-year-old female had frequent hypoglycaemias on combination

therapy of metformin and gliclazide. As a result, sitagliptin was

initiated, and gliclazide dose was reduced. Six months after

sitagliptin introduction, there was a significant reduction in

frequency of hypoglycaemic episodes and a slight decrease of

fructosamine levels from 265µmol/L to 255µmol/L (equivalent reduction

in HbA1c of 0.2%). Her weight increased by 2.2 kg.

Patient 5.

A 45-year-old female had suboptimal glycaemic control despite

combination treatment with metformin and gliclazide. Sitagliptin was

added as 3rd line agent, leading to

significant fructosamine reduction from 354µmol/L to 258µmol/L

(equivalent reduction in HbA1c of 1.9%) and weight loss of 6 kg over 6

months.

Overall, four out of the five patients were

responders to sitagliptin therapy, as evidenced by a significant

reduction in fructosamine in two patients by 77 and 96µmol/L

(equivalent reduction in HbA1c of 1.5 and 1.9%). In the other two

patients, there was a significant reduction in the frequency of

hypoglycaemia with relatively stable glycaemic control. In one case

sitagliptin did not result in glucose lowering and was appropriately

stopped after 6 months. No patients exhibited signs/symptoms of

pancreatitis or cholecystitis, while liver function tests did not

change significantly after sitagliptin initiation. In total, no

significant side effects were reported.

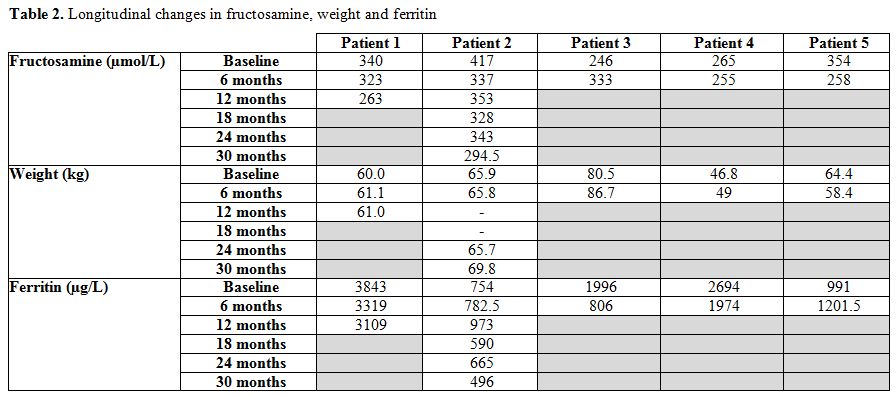

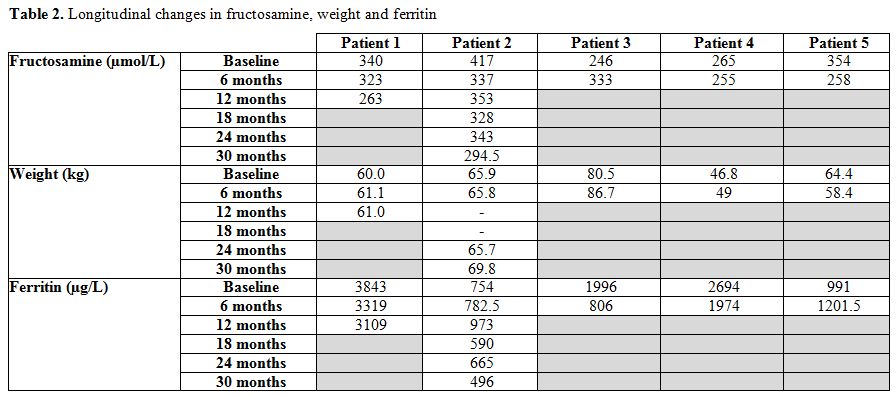

As seen in Table 2, there was no relationship between fructosamine and ferritin levels which could explain changes in glycaemic control.

|

Table 2. Longitudinal changes in fructosamine, weight and ferritin |

Discussion

Our

case series shows that the DDP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin is an effective

glucose-lowering agent and is associated with low rate of

hypoglycaemias in patients with β-TM. Four out of five patients

initiated on sitagliptin were responders, either by achieving a

reduction in fructosamine levels or by experiencing less frequent

hypoglycaemic episodes. These findings are in keeping with RCTs in

patients with type 2 DM showing that sitagliptin improves glycaemic

control and reduces the rate of hypoglycaemias. The lack of association

between changes in fructosamine and ferritin indicates that

intensification of glycaemic control could not be attributed, at least

in our small cohort, to changes in iron chelation therapy.

Whilst

previous studies have reported sitagliptin to be weight neutral in

patients with DM, a mixed response was recorded in our cohort.[10]

Two patient maintained stable weight, one achieved reduction and two

others had weight gain. Besides the effect of sitagliptin, weight gain

might be attributed to factors such as poor adherence to dietary

advice, concomitant use of sulfonylureas and psychosocial factors.

Data

review of this case series did not raise any safety concerns. Previous

studies in participants with type 2 DM have shown possible association

of DPP-4 inhibitors with pancreatitis, increased risk of infections and

arthralgias,[11,12] although the overall incidence of serious adverse events is extremely low.[13] In view of conflicting evidence about whether sitagliptin increases the risk of pancreatitis,[14-16] current consensus is that DPP-4 inhibitors should be avoided in patients with a history of pancreatitis.[15]

However gallstones, commonly seen in patients with β-TM, are not a

contraindication for the use of sitagliptin. The European spontaneous

reporting database recently published 65 reports of cholecystitis in

patients with type 2 DM treated with sitagliptin, suggesting

sitagliptin may increase the risk of cholecystitis.[17]

However a large population-based study showed that DPP-4 inhibitors

were not associated with an increased risk of bile duct and gallbladder

disease.[18] In contrast to initial reports showing

an increased incidence of nasopharyngeal and upper respiratory tract

infections in association with sitagliptin, contemporary data do not

suggest any increased risk of infection.[19] A recent FDA warning reported sitagliptin has been rarely associated with severe joint pain through an unknown mechanism.

The

main strength of our study is that this is the first study ever

conducted reporting real-life use of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with

β-TM. Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, the

very small number of patients and the lack of comparator group.

At

present sitagliptin as well as other modern antidiabetic agents such as

s GLP-1 agonists and SGLT-4 inhibitors are increasingly used with great

success in patients with type 2 diabetes, offering optimal glycaemic

control and reducing the rate of hypoglycaemic episodes without

associated weight gain. However the lack of evidence on efficacy and

safety of these agents in patients with thalassaemia restricts access

of these patients to potentially valuable therapeutic options. While

findings from studies in the general population may apply to patients

with β-TM, these patients have a different pathophysiological basis of

diabetes and also have multiple comorbidities and complex needs. These

reasons highlight the urgency to generate high quality evidence in this

field.

Whilst our data supports the potential for sitagliptin

use as add-on therapy to metformin and sulfonylurea combination therapy

in patients with β-TM, we recommend considering also the use of

sitagliptin as second line agent to metformin in agreement with

international guidelines for patients with type 2 DM.[3]

The rationale behind this is that sulfonylureas, which are commonly

used nowadays as second-line agents, are associated with high rate of

hypoglycaemia and significant weight gain. Specifically, optimal

candidates for switching from sulfonylurea to sitagliptin in order to

decrease significantly symptomatic hypoglycaemia are patients with

dominant insulin resistance.[20] Taking into account

that very little to no data exist on sitagliptin use in patients with

β-TM, the benefits and risks of therapy should be carefully considered

and always discussed with the patient. If patient and doctor make a

decision to start sitagliptin, they should specify the goals of this

therapy. For example, sitagliptin should be usually discontinued if the

patient does not achieve fructosamine reduction of at least 25µmol/L

(equivalent HbA1c reduction of 0.5%) within 6 months of initiation or

does not experience a significant reduction in the frequency of

hypoglycaemic episodes. Finally, initiation of sitagliptin should take

place only under the guidance, supervision and close monitoring of a

Diabetologist with experience in management of patients with β-TM and

DM.

Conclusion

Our

study provides some evidence that sitagliptin could be considered for

use in selected patients with β-TM and DM. To the best of our

knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the efficacy and

safety of a modern oral antidiabetic agent in patients with β-TM and it

could facilitate access of this population to sitagliptin.

References

- Barnard M, Tzoulis P. Diabetes and thalassaemia. Thalassemia Reports, 2013. 3(1s): p. 18. https://doi.org/10.4081/thal.2013.s1.e18

- Monge

L, Pinach S, Caramellino L, Bertero MT, Dall'omo A, Carta Q. The

possible role of autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of diabetes in

B-thalassemia major. Diabetes Metab, 2001. 27(2 Pt 1): p. 149-54.

PMid:11353881

- Inzucchi

SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters

AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. Management of Hyperglycemia in

Type 2 Diabetes, 2015: A Patient-Centered Approach: Update to a

Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association and the

European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2015.

38(1): p. 140-149. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2441 PMid:25538310

- Chen

XW, He ZX, Zhou ZW, Yang T, Zhang X, Yang YX, Duan W, Zhou SF. Clinical

pharmacology of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors indicated for the

treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clinical and Experimental

Pharmacology and Physiology, 2015. 42(10): p. 999-1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.12455 PMid:26173919

- Nauck

MA, Meininger G, Sheng D, Terranella L, Stein PP, Sitagliptin Study 024

Group. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor,

sitagliptin, compared with the sulfonylurea, glipizide, in patients

with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin alone: a

randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Diabetes, Obesity and

Metabolism, 2007. 9(2): p. 194-205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00704.x PMid:17300595

- Seck

T, Nauck M, Sheng D, Sunga S, Davies MJ, Stein PP, Kaufman KD, Amatruda

JM, Sitagliptin Study 024 Group. Safety and efficacy of treatment with

sitagliptin or glipizide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately

controlled on metformin: a 2-year study. Int J Clin Pract, 2010. 64(5):

p. 562-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02353.x PMid:20456211

- Ishikawa

M, Takai M, Maeda H, Kanamori A, Kubota A, Amemiya H, Iizuka T, Iemitsu

K, Iwasaki T, Uehara G, Umezawa S, Obana M, Kaneshige H, Kaneshiro M,

Kawata T, Sasai N, Saito T, Takuma T, Takeda H, Tanaka K, Tsurui N,

Nakajima S, Hoshino K, Honda S, Machimura H, Matoba K, Minagawa F,

Minami N, Miyairi Y, Mokubo A, Motomiya T, Waseda M, Miyakawa M, Naka,

Y, Terauchi Y, Tanaka Y, Matsuba I. Factors Predicting Therapeutic

Efficacy of Combination Treatment With Sitagliptin and Insulin in Type

2 Diabetic Patients: The ASSIST-K Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine

Research, 2015. 7(8): p. 607-612. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2149w PMid:26124906 PMCid:PMC4471747

- Cappellini M-D C. A., Eleftheriou A, Piga A, Porter J, Taher A. Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Thalassaemia. 2nd Revised edition ed. 2008: Thalassaemia International Federation.

- Juraschek

SP, Steffes MW, Selvin E. Associations of Alternative Markers of

Glycemia with HemoglobinA1c and Fasting Glucose. Clinical Chemistry,

2012. 58(12): p. 1648-1655. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.188367 PMid:23019309 PMCid:PMC3652236

- Ahuja

V, Chou CH. Novel Therapeutics for Diabetes: Uptake, Usage Trends, and

Comparative Effectiveness. Curr Diab Rep, 2016. 16(6): p. 47.

- Amori

RE, Lau J, Pittas AG. Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2

diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 2007. 298(2): p.

194-206. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.2.194 PMid:17622601

- Richter

B, Bandeira-Echtler E, Bergerhoff K, Lerch C. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

(DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev, 2008(2): p. Cd006739. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd006739.pub2

- Gooßen

K, Gräber S. Longer term safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in

patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and

meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 2012. 14(12): p.

1061-1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01610.x PMid:22519906

- Deacon

CF, Lebovitz HE. Comparative review of dipeptidyl peptidase-4

inhibitors and sulphonylureas. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.12610

- Scheen

AJ. Safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treating type 2

diabetes. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2015. 14(4): p. 505-24. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2015.1006625 PMid:25630605

- Egan

AG, Blind E, Dunder K, de Graeff PA, Hummer BT, Bourcier T, Rosebraugh

C. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs--FDA and EMA assessment. N

Engl J Med, 2014. 370(9): p. 794-7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1314078 PMid:24571751

- Pizzimenti

V, Giandalia A, Cucinotta D, Russo GT, Smits M, Cutroneo PM, Trifirò G.

Incretin-based therapy and acute cholecystitis: a review of case

reports and EudraVigilance spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting

database. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 2016. 41(2):

p. 116–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12373 PMid:26936090

- Faillie

J, Yu OH, Yin H, Hillaire-Buys D, Barkun A, Azoulay L. Association of

Bile Duct and Gallbladder Diseases With the Use of Incretin-Based Drugs

in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA Internal Medicine,

2016. 176(10): p. 1474-1481. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1531 PMid:27478902

- Yang

W, Cai X, Han X, Ji L. DPP-4 inhibitors and risk of infections: a

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes/Metabolism

Research and Reviews, 2016. 32(4): p. 391-404. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.2723 PMid:26417956

- Kim

HM, Lim JS, Lee B-W, Kang E-S, Lee H C, Cha B-S. Optimal Candidates for

the Switch from Glimepiride to Sitagliptin to Reduce Hypoglycemia in

Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrinology and Metabolism,

2015. 30(1), p. 84–91. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2015.30.1.84 PMid:25325279 PMCid:PMC4384675

[TOP]