Alessia Castellino, Elisa Santambrogio, Maura Nicolosi, Barbara Botto, Carola Boccomini and Umberto Vitolo

Città della Salute e della Scienza University and Hospital, Hematology Unit, Turin, Italy

Corresponding

author: Alessia Castellino. Città della Salute e della Scienza

University and Hospital, Hematology Unit, Turin, Italy. E-mail:

acastellino@cittadellasalute.to.it

Published: Dacember 7, 2017

Received: November 2, 2016

Accepted: December, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017009 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.009

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Follicular

lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which

typically affects mature adults and elderly, whose median age at

diagnosis is 65 years. The natural history of FL appears to have been

favorably impacted by the introduction of Rituximab. Randomized

clinical trials demonstrated that the addition of rituximab to standard

chemotherapy induction has improved the overall survival and new

strategies of chemo-immunotherapy, such as Bendamustine combined with

Rituximab, showed optimal results on response and reduced hematological

toxicity, becoming one of the standard treatments, particularly in

elderly patients. Moreover, maintenance therapy with Rituximab

demonstrated improvement of progression-free survival. Despite these

exciting results, FL is still an incurable disease. It remains a

critical unmet clinical need finding new prognostic factors to identify

poor outcome patients better, to reduce the risk of transformation and

to explore new treatment strategies, especially for patients not

candidate to intensive chemotherapy regimens, such as elderly patients.

Some progress was already reached with novel agents, but larger and

more validated studies are needed. Elderly patients are the largest

portion of patients with FL and represent a subgroup with higher

treatment difficulties, because of comorbidities and smaller spectrum

for treatment choice. Further studies, focused on elderly follicular

lymphoma patients, with their peculiar characteristics, are needed to

define the best-tailored treatment at diagnosis and at the time of

relapse in this setting.

|

Introduction

Follicular

lymphoma (FL) is the most common form of indolent lymphoma and accounts

for 20% to 30% of all newly diagnosed non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL)[1]

and with an annual incidence of 1.6- 3.1/ 100000 cases in western

countries.[2,3] It typically occurs in mature and older adults, the

median age of 65 years and with frequently in patients older than 75

years. FL is considered as an indolent but incurable disease with a

median life expectancy of approximately ten years. Despite advances in

the treatment of FL, most of the patients remain incurable and, in 10

years, 15% to 28% of cases will transform into an aggressive phenotype,

typically diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

FL arises from

malignant transformation of normal germinal center (GC) B cells and, in

approximately 85% of cases, harbours the translocation

(14;18)(q32;q21), resulting in an inability to down-regulate expression

of the anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), which is absent

in normal GC B cells.[4] Most tumors are characterized by recurrent

secondary genetic alterations that may provide a growth advantage,

including genomic gains, losses, and mutations.

The histological

report should give the diagnosis according to the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification.[5] Grading of lymph node biopsies is

performed according to a number of blasts/high power field.

The

treatment depends on the stage of the disease, so initial staging

should be thorough, particularly in the small proportion of patients

with localized stages I and II (10%–15%). Staging should include a

computed tomography (CT) scan, Positron emission tomography(PET)-CT and

a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy.[6] Complete blood test, including

chemistry and screening for HIV, HCV, and HBV must be done at

baseline. The staging is performed according to the Ann Arbor

classification system.[7]

The prognosis of FL remains

heterogeneous. Thus, prognostic indices are necessary to guide the

physician’s decision-making process and to design clinical trials.

Several prognostic factors have been identified in patients with FL,

including age, stage, tumor burden, bone marrow (BM) involvement,

systemic symptoms, performance status (PS), serum lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH),

hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and β2-microglobulin.[8-9]

As

result of international cooperation, the FL International Prognostic

Index (FLIPI) was established in 2004.[10] This model divided patients

affected by FL in three different classes of risk according to five

parameters, including age over 60 years, Ann Arbor stage III or IV,

hemoglobin value <12 mg/dL, more than four nodal sites involved,

increased value of serum LDH. However, the FLIPI was born before

rituximab era and was based on retrospective data, so a revised FLIPI 2

(incorporating beta2 microglobulin, the diameter of largest lymph node,

bone marrow involvement, and hemoglobin level) was introduced.[11]

Extended

knowledge of the biology of tumor lead to a clinic-genetic risk score

(m7-FLIPI) based on mutation status of 7 candidate genes,[12] but it is

not standardized yet.

Elderly Patient: the Impact of Age

Many

patients with FL are elderly and age by itself (>60 years) has been

shown to be one of the most powerful poor prognostic features into

Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI).[10]

However, so far there are few clinical trials specifically designed for

these patients; in clinical practice elderly patients are often managed

in a palliative way or with the adoption of a “watchful waiting” policy

in low tumor burden or asymptomatic patients or, in most of the cases,

the planned whole treatment is stopped because of treatment-related

toxicity.

The clinical approach to elderly patients is a complex

issue and age alone could not be enough to guide the treatment

strategy. Older patients show alterations in tumor-host biology and

comorbidities which result in changes in pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics, may be a possible reason for poorer outcome in this

setting.[13-14] Moreover, it is well known that immune system in older

adults displays a deterioration of DNA-damage repair mechanisms and a

decrease of both cellular mediated and humoral immune response.[15-16]

Older patients are also more likely to develop cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity, kidney injury, and mucositis.

Indeed,

to explain the worst prognosis in elderly patients, some studies

suggested that lymphomas could be biologically more complex and

aggressive in older people.

Some evidence suggested for example

that CD69 expression on lymphoma cells was related to a poor outcome,

with a prognostic value independent from the treatment, evaluated in a

population of older adults.[12] A dense infiltrate of CD4-positive T

cells, especially when located interfollicular, was a good prognostic

sign irrespective of treatment. Dense infiltrate of FoxP3-positive T

cells and CD68 positive macrophage, especially with an interfollicular

component, was associated with better survival. However, contradictory

results regarding the

correlation between treatment heterogeneity

and clinical impact have been reported by a Finnish group:[17] they

showed that the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy is the cause of

reversing the negative prognostic impact of high macrophage content,

showed in previous series,[18] into favorable factor. In the rituximab

era, the high macrophage content showed a positive impact on prognosis

at both diagnosis and relapse, and it is likely to be associated with

antibody-dependent cytotoxicity. It was noted that the relative number

of lymphoma-associated macrophage is lower in younger patients.[18-19]

Also, the prognostic value of minimal residual disease (MRD) was

firstly evaluated in a cohort of elderly patients.[20]

Even if in

elderly patients there were biological differences compared to FL in

younger people, many trials showed that these patients, if treated with

a correct dose-intensity chemotherapy, could reach a response rate

similar to a younger population.[15]

According to the results of

these studies, an accurate, complete evaluation of elderly patients

affected by lymphoma remains a central issue for a good clinical

practice, in order to administer a tailored dose-intensity therapy to

obtain the best outcome for these patients.

The Comprehensive

Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a score used to make a whole evaluation

of elderly people with cancer, based on age, comorbidities and

functional abilities of daily living and it represents an important

tool in older people, in order to personalize the treatment

discriminating among fit, unfit or frail patients.[21] It is based on

many different tests including: ADL scale, IADL scale, evaluation of

comorbidities (Charlson’s scale and CIRS-G scale), Mini Mental State

Examination (MMSE), evaluation of nutritional state (20% of patients

older than 70 years is underfed)[22] and socio-economic state. ADL

scale (or Katz’s scale)[23] is based on the possibility to perform

regular daily activities (such as eating, washing, dressing, etc..);

IADL scale (or Lawton’s scale)[24] evaluates the self-government in

social function, such as phoning, shopping, money management, etc. MMSE

shows alterations in more than 50% of people older than 85 years[25]

and Geriatric Depression Scale demonstrates a depression in 20% of

patients older than 70 years.[26]

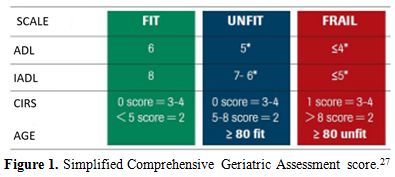

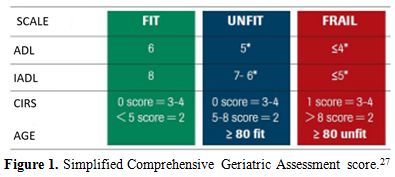

On this basis, Tucci et al.[27]

conducted a pilot trial to analyze if a simplified CGA model could

identify elderly patients with aggressive lymphoma eligible for

anthracycline therapy on 84 patients aged more than 65 years. The

Italian Lymphoma Foundation (FIL) recently performed a prospective

multicenter trial to validate a simplified CGA evaluation model in a

cohort of 173 elderly patients with lymphoma. Based on this simplified

CGA elderly patients were classified into three categories: fit,

unfit and frail (Figure 1). The

results of this study showed that the 2y-OS was significantly better in

fit than in unfit or frail patients (84% vs. 47%, p <0.0001).

Survival in unfit and frail people was superimposable. CGA was

confirmed as very useful to guide clinical therapeutic decisions and to

identify elderly patients who can benefit from a curative approach,

while further efforts are needed to better tailor therapies in not fit

population.[28] However, it must be noted that this trial was conducted

in patients with aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and it was

not validated in a cohort of FL elderly patients.

|

Figure 1. Simplified Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment score.[27] |

Recommendations

of the Authors: an accurate whole evaluation of elderly patient

affected by lymphoma is a central issue, and it represents the first

step for a tailored dose-intensity therapy, to obtain the best outcome

for these patients; CGA and comorbidity scale are useful instruments to

guide therapeutic decisions for a good clinical practice.

Treatment

An

ideal therapy for older adults should be brief, feasible in an

outpatient setting, effective and possibly with low related toxicity.

Despite

a variety of treatment approaches are currently available for the

initial treatment of follicular lymphoma, there are no universally

accepted first-line chemotherapy regimens for advanced stage disease.

The introduction of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab) has

definitely improved the outcome of these patients as shown by many

studies. Rituximab and standard chemotherapy show no significant

overlapping toxicities. This evidence provides the rationale for

combining chemotherapy regimens with Rituximab, considered at

present the standard component of first-line treatment with a

complete remission rate ranging from 20 to 75%, a 4 years-progression

free survival (4y-PFS) improved at 61% (p=0.005) and a 4y-overall

survival (4y-OS) of 91% (p < 0.001).[29]

First-Line Therapy

In

the small proportion of limited non-bulky stages I–II, radiotherapy

alone is the preferred choice. Several centers reviewed the long-term

outcome of RT alone and demonstrated a freedom from relapse of 55%,

44%, 43% and 35% at 5, 10, 15 and 20 years of follow-up. Relapse

occurs in only 10% of high-risk patients at 10 years.[30-31]

The

most recent and largest retrospective study of 6,568 patients with

follicular lymphoma stage I or II diagnosed between 1973 and 2004 was

based on SEER data. Compared to the no RT group, patients who received

RT had higher rates of disease-specific survival (DSS) at 5 (81 % vs.

90%), 10 (66 % vs. 79%), 15 (57 % vs. 68%), and 20 (51 % vs. 63%)

years. Overall survival was also improved for patients who received

initial RT. Relapses usually occur distant from the RT site and are

rare after 10 years (1-11 %).[32] Data demonstrates that RT involved

filed 24 Gy is indicated to obtain a curative intent, whereas low dose

schedule (2x2 Gy) shows mainly a palliative effect.[33]

An initial

strategy of observation can also be considered. A Stanford report of

stage I and II patients who received no initial therapy showed that

more than half of the 43 patients did not require any therapy at a

median of 6 years, and 85% of patients were alive at 10 years.[34]

However this was performed in a small series of patients, and W&W

must be considered in selected case to avoid the usual side effects of

radiation (e.g. sicca syndrome, thyroid malfunction, mucositis,

myeloablative suppression, bladder disorders).

Asymptomatic,

low-tumor-burden patients may be candidates for a strategy of watch and

wait. The Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria

are commonly used to assess tumor burden. For high-tumor-burden FL,

GELF criteria include at least 1 of the following: 3 distinct nodal

sites, each ≥3 cm; single nodal site ≥7 cm; symptomatic splenomegaly;

organ compression or compromise; pleural effusions, ascites. Therapy is

indicated in the presence of 1 criteria of high-tumor-burden; B

symptoms or any systemic symptoms; LDH or B2M above the upper limit of

normal. In the absence of high-tumor-burden criteria, there are no

benefits on overall survival by starting immediately specific

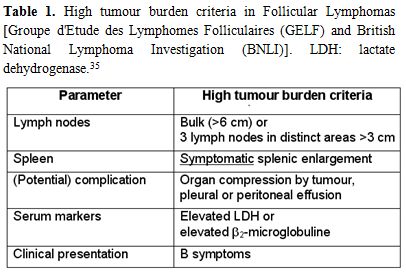

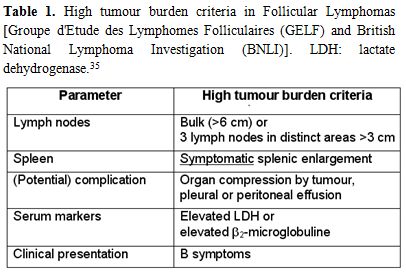

treatment.[35] (Table 1)

|

Table 1. High tumour burden criteria in

Follicular Lymphomas [Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF)

and British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI)]. LDH: lactate

dehydrogenase.[35] |

The

F2-study, which compared the first-line treatment with Rituximab to the

Watch and Wait approach (W&W), did not show any differences on

freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) andoverall survival rates after

treatment in a selected prognostically favorable group. The median

studied population age was similar in two groups, 59 years (range 33-94

yrs) in W&W arm and 56 years (range 23-83 yrs) in Rituximab

receiving arm. Patients older than 60 years were respectively 46% and

39%.[36] Certainly, for elderly patients with a reduced life

expectancy, a W&W strategy is most appropriate in a

low-tumor-burden setting, as therapy is unlikely to alter the life

expectancy and could have detrimental effects on quality of life.

A

systemic more aggressive therapy is indicated for advanced stage FL

with high-tumor-burden or adverse prognostic features. At present,

advanced stage FL is still considered incurable, even if the discovery

and introduction of Rituximab as standard therapy in FL has

dramatically improved overall survival (OR) and progression-free

survival (PFS).[37-38] The optimal chemotherapy to associate with

Rituximab remains unsettled, and in clinical decisions, age,

comorbidities, and patients willingness have to be considered. The most

common associations were R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), R-CVP (rituximab,

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), and R-fludarabine, even

if some of these options are not advisable in elderly patients for

their severe hematological toxicity. A randomized comparison of these

regimens indicated R-CHOP has the best risk-benefit profile, as it is

more active than R-CVP and less toxic than

Rituximab-fludarabine-mitoxantrone.[39]

In the last 20 years, the

re-discovery of Bendamustine has opened a new scenario in Indolent

Lymphoma treatment regimens. A phase 3 trial from the Study group

Indolent Lymphoma (StiL)[40] randomized 549 patients with

high-tumor-burden indolent NHL and mantle cell lymphoma (median age 64

years) to receive bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2, with rituximab 375 mg/m2

on day 1, every 28 days (the BR group) or to receive standard R-CHOP

chemotherapy every 21 days. The overall response rates (ORRs) were

similar in the two groups (92.7% vs. 91.3%, respectively), but the

complete response (CR) was significantly higher in the BR group (39.8%)

compared with the R-CHOP group (30.0%). Evaluating just the FL

patients, with a median follow-up of 45 months, the median PFS was

significantly longer after BR compared with R-CHOP (not reached vs.

40.9 months). OS did not differ. There was less hematologic toxicity,

alopecia, infections, peripheral neuropathy, and stomatitis with BR.[40]

The

successful results of Bendamustine in FL were also confirmed in a

randomized, phase 3 trial (Bright) which enrolled 447 patients with

untreated indolent NHL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) to received

Rituximab-Bendamustine (BR) or standard therapy R-CHOP/R-CVP. 70% of

study’s population were FL with a median age of 60 years in BR group

and 58 years in R-CHOP/R-CVP group. The authors demonstrated the no

inferiority of BR to standard treatments, with ORR of 97% (CR in 31%)

vs. 91% (CR 25%) respectively. The toxicity pattern was different,

showing a higher incidence of nausea, vomiting and skin reactions in BR

arm, but rarely severe events (3%). Even if GCSF was used mainly in

R-CHOP, this group reported the higher number of cases of 3-4 grade

neutropenia.[41]

Another possible choice of treatment in FL is

Radioimmunotherapy, using an anti-CD20 antibody conjugated with a

radionuclide, 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin). It is recommended in

consolidation therapy, but it has also been evaluated in the first-line

treatment of advanced stage FL. In a phase II trial Zevalin was

administrated 8 days after a single dose of Rituximab (at 250 mg/mg).

50 patients were enrolled, and 25 of them had more than 60 years.

Objective response was in 94% of patients, with 86% of CR. Progression

or relapsed was reported in 34%, and 11% died for progression. At a

median follow-up of 38.8 months, median PFS and OS were not reached.

Three years PFS and OS were respectively 63% and 90%. Grade 3-4

myelosuppression was limited, with 30% of neutropenia and 26% of

thrombocytopenia. The study showed good efficacy and safety of single

dose of Zevalin in untreated patients, even in the elderly

population.[42]

Recommendations of the Authors: In limited stage,

FL radiotherapy alone is the preferred choice. In elderly patients with

advanced stage, low tumor burden FL the watch and wait approach is the

most appropriate strategy. Treatment is a need in high tumor burden

symptomatic FL. The introduction of Rituximab improved OS and PFS, but

the optimal chemotherapy to associate remains unsettled, above all in

elderly patients, for whom age, comorbidities, and frailty should be

considered for clinical decision. R-Bendamustine may be regarded as the

first choice, but also CHOP/CVP/FND are suitable alternatives, also in

elderly patients.

Maintenance/Consolidation Therapy

After first line

therapy, the majority of patients achieve complete remission of the

disease, however, most patients relapse. On this basis, many different

strategies were studied to delay the relapse and to ameliorate the

outcome of these patients, such as maintenance or consolidation

treatment.

Rituximab maintenance for 2 years improves PFS (75%

versus 58% after 3 years, p<0.0001), whereas a shorter maintenance

period results in an inferior benefit.[43-44]

As consolidation

strategy, radioimmunotherapy with Zevalin demonstrated to prolong PFS

after chemotherapy. However, the advantage after rituximab-containing

regimens has been not fully evaluated. This option would remain a valid

alternative in patients not eligible for high-dose chemotherapy and

autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) even if its benefit seemed

to be inferior in comparison to Rituximab maintenance for 2 years.[45]

Indeed a Spanish randomized phase II trial compared consolidation with

a single dose of Zevalin (arm A) versus maintenance with Rituximab (arm

B) for 2 years in newly diagnosed FL responding to R-CHOP. 146 patients

were enrolled (median age 55 yrs), 124 were randomized to induction

therapy and 22 patients were excluded for neutropenia or

thrombocytopenia, patient decision and unsatisfying response (< PR).

51% received Zevalin and 49% Rituximab. After a median follow-up of 37

months 32 patients relapsed/progressed with a 36-months PFS of 64% in

Zevalin arm and 86% with Rituximab. Number of PR which increased to CR

during maintenance were 50% and 46% in arm A, and B respectively. With

Zevalin 5 and 6 cases of >3-grade thrombocytopenia and

neutropenia were respectively described, whereas only one case

of >3-grade neutropenia was reported in Rituximab group. In

conclusion, maintenance with Rituximab was superior to Zevalin, in term

of PFS and toxicity. At present, no sufficient data are available on

long-term follow-up.[46]

Focus on the Phase III Trial ML17638[47]

The

goal of treatment in elderly patients with FL is to maintain clinical

efficacy while minimizing toxicity and preserving the patient’s quality

of life. The combination of rituximab and fludarabine-based

chemotherapy (fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone; R-FND) has been

shown to be well-tolerated and efficient also in elderly patients.[48]

Regardless of induction therapy, rituximab maintenance has been shown

to prolong the duration of response in treatment-naive patients as well

as in those with relapsed/refractory disease.[49-52] However, none of

these trials were designed specifically for elderly patients, and there

is little data on maintenance therapy in the elderly. On

these basis the phase III trial ML17638 was designed by the Fondazione

Italiana Linfomi, with the aim to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a

short rituximab maintenance regimen compared to no further treatment in

elderly patients with advanced FL who had responded to a brief

first-line treatment regimen consisting of 4 courses of R-FND chemoimmunotherapy followed by 4 weekly doses of rituximab consolidation.[47]A

total of 234 elderly patients affected by treatment-naïve FL were

enrolled. It must be noted that median age was 66 years (range 60-75)

and patients aged more than 70 years were 23%; 41% of patients had no

comorbidities according to CGA score, while 23% of them presented more

than 2 concomitant comorbidities. All patients enrolled began a

chemoimmunotherapy with 4 monthly courses of R-FND followed by 4 weekly

cycles of rituximab consolidation. Of these, 202 responders were

randomized to rituximab maintenance (Arm A) once every 2 months for a

total of 4 doses or observation (Arm B). Median age in Arms A and B

were 66 and 65 years (range: 60-75). After induction and consolidation

therapy, the ORR was 86%, with 69% CR. After a 42 month median

follow-up from diagnosis, 3y-PFS and 3y-OS were 66% (95%CI:59-72%) and

89% (95%CI: 85-93%), respectively. After randomization, 2y- PFS was 81%

for rituximab maintenance versus 69% for observation with an HR of 0.63

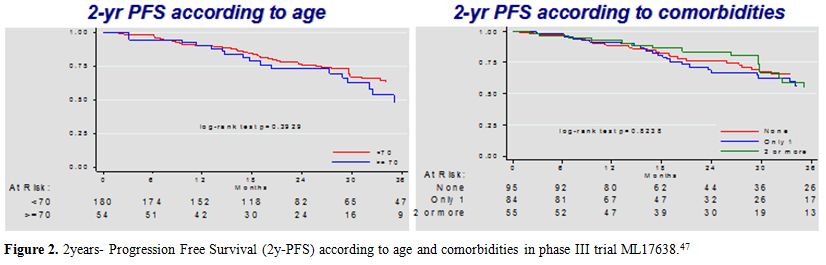

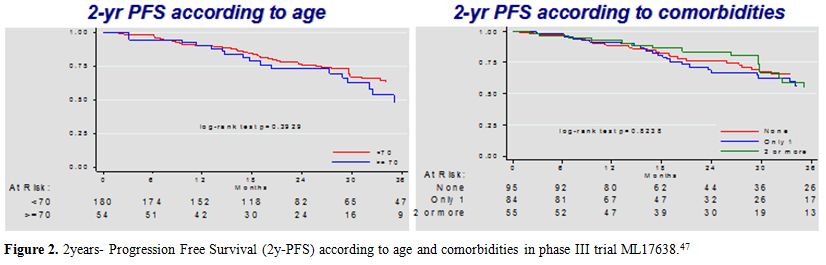

(95%CI:0.38-1.05, p=0.079), although not statistically significant. Age

did not appear to have any significant effect on 3-year PFS. The

subgroup of patients below 70 years had a 3-year PFS of 67% (95%CI:

59-73%), compared to 63% (95%CI: 48-75%) for those ≥70 years. There

were no differences in 2y-PFS for patients with none, one or two or

more comorbidities. (Figure 2).

These data suggested that this therapy scheme could be safely

administered to older adults and also in those with comorbidities.

|

Figure 2. 2 years- Progression Free Survival (2y-PFS) according to age and comorbidities in phase III trial ML17638.[47] |

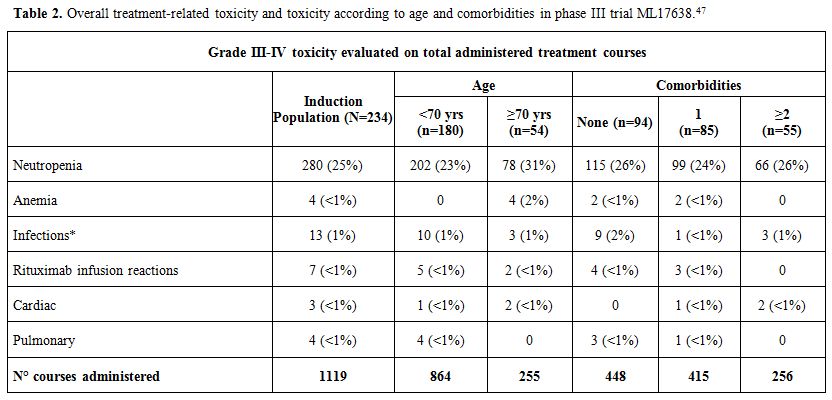

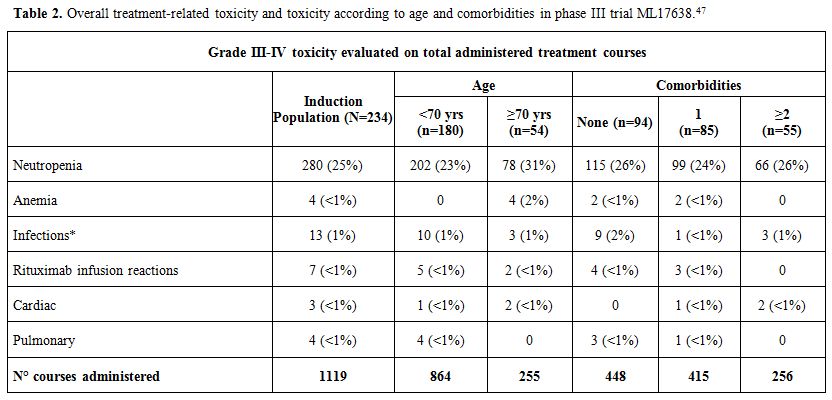

No differences between the two arms were detected by OS (9 deaths occurred, 5 in the maintenance and 4 in the observation arms).As

for safety profile of the treatment, the most frequent Grade 3-4

toxicity was neutropenia (25% of treatment courses), with 13

infections. Two toxic deaths (0.8%) occurred during treatment. Overall,

the regimen was well-tolerated. In the table (Table 2)

we reported the overall toxicity, treatment-related and other,

according to age and comorbidities reported as events in a total of

1119 treatment courses administered to 234 patients. The treatment was

well-tolerated, and there was presence of comorbidities, no significant

differences were found in the frequency of AEs.

|

Table 2. Overall treatment-related toxicity and toxicity according to age and comorbidities in phase III trial ML17638.[47] |

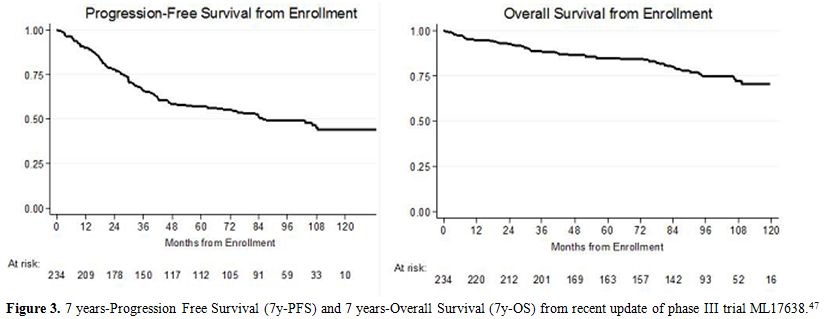

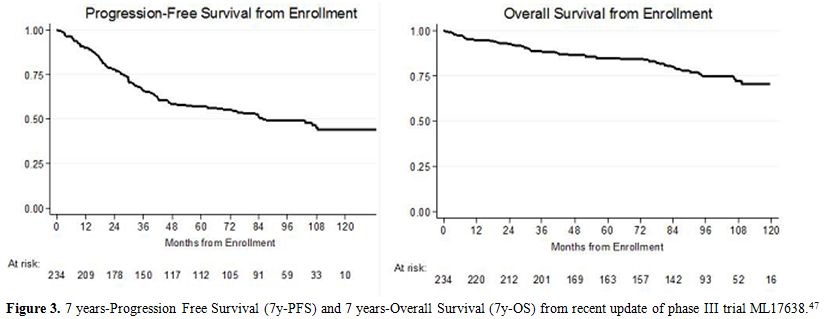

Here

we present the results of a recent update of a prolonged follow-up of

the ML17638 trial, at 96 months from enrollment and 87 from

randomization. We collected data from 127 of 146 patients evaluable. Long-term

follow-up data confirmed the overall favorable outcome, with a 5y-PFS

of 57% and a 7y-PFS of 51%. Globally 5y-OS and 7y-OS were 85% and 80%

respectively (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. 7 years-Progression Free

Survival (7y-PFS) and 7 years-Overall Survival (7y-OS) from recent

update of phase III trial ML17638.[47] |

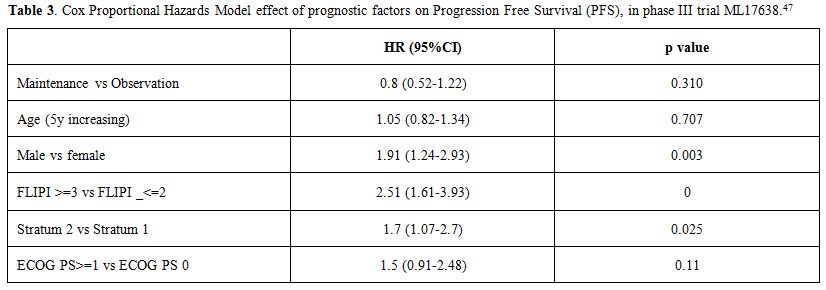

The

prognostic impact of FLIPI score was confirmed, with a benefit in both

PFS and OS in patients with a low-intermediate FLIPI score. The 7y-PFS

was 67% in patients with low-intermediate FLIPI vs. 38% in patients

with high FLIPI (p<0.001), moreover, 7y-OS was 86% vs. 75%

respectively in the two different prognostic groups (p=0.03). As

for maintenance treatment, no differences were shown between

maintenance and observation arms, with a 7y-PFS of 55% vs. 52%

respectively (p=0.331, HR 0.8).In

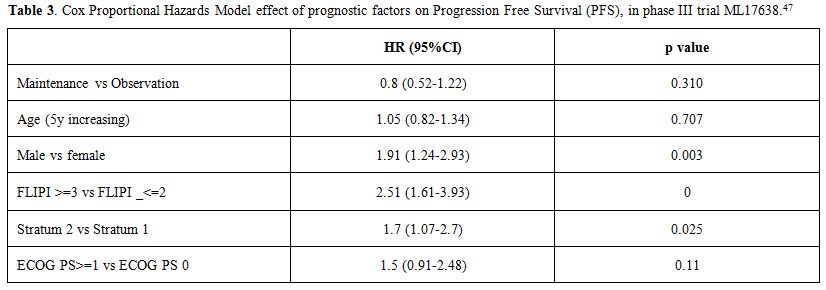

a multivariate analysis, male sex, the absence of molecular remission

and high-intermediate/high FLIPI score were confirmed as unfavorable

prognostic factors, with HR 1.91 (p=0.003), HR 1.7 (p=0.025) and HR

2.51 (p<0.0001) respectively.(Table 3)

|

Table 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Model

effect of prognostic factors on Progression Free Survival (PFS), in

phase III trial ML17638.[47] |

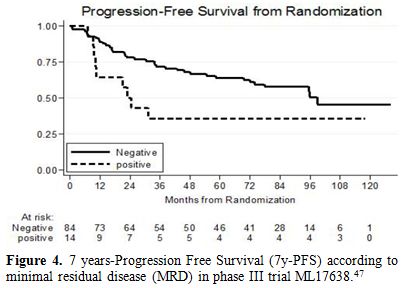

No

differences were identified between the two arms maintenance vs.

observation in any subgroup neither in higher FLIPI score patients. Also

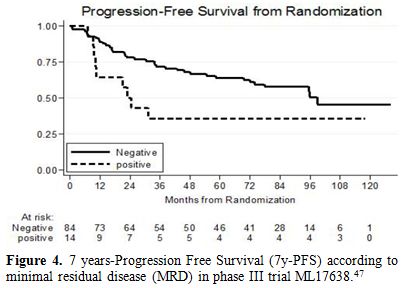

in this updated follow-up of the study, the achievement of a negative

PCR at the end of treatment (complete molecular remission) was

confirmed to be a favorable prognostic factor, predictive of a better

outcome, with a 7y-PFS of 58% vs 36% (p=0.084) respectively in patients

without or with minimal residual disease. (Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. 7 years-Progression Free Survival (7y-PFS) according to minimal residual disease (MRD) in phase III trial ML17638.[47] |

No

differences between the two arms maintenance vs. observation were

observed in patients with minimal residual disease (MRD positive) at

the end of induction treatment. As

far as toxicities are concerned, 7y-follow up of ML17638 trial showed

similar toxicities in both maintenance and observation arm, for

infections, cardiac events, and secondary tumors. In particular, 13

secondary malignancies were observed in the maintenance group vs. 16 in

patients who underwent observation alone, with a cumulative incidence

of 13.9% (95% CI: 6.4 to 21.4) vs. 10.9% (95% CI: 4.4 to 17.4)

respectively.These

results underscore the importance of developing tailored therapies for

the elderly, exploring the use of brief chemoimmunotherapy regimens

beyond the age of 65.As

for maintenance treatment, the lack of statistical significance in our

findings may have different causes. First rituximab maintenance

may have a small clinical benefit, which could not be demonstrated with

the sample size of this study. However, the lack of statistically

significant difference is also confirmed at a longer follow-up.

Moreover, the maintenance strategy used in the present study was

relatively brief compared to “classical” 2-years maintenance, and this

may be the cause of the reduced efficacy. Furthermore, in our trial,

the results obtained in observation arm were better than expected, and

this may be the reason for a smaller absolute difference compared to

maintenance arm. Indeed, the lack of differences in PFS in this trial

suggests that the benefit of rituximab maintenance could be different

on the basis of induction chemotherapy administered. The PRIMA

study[43] allowed 3 different induction chemotherapy schemes

(R-CHOP, R-CVP and R-FCM (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone),

but the group of patients who received R-FCM was smaller (only 45

compared to 272 for R-CVP and 885 for R-CHOP) and was the only one

which did not seem to benefit from maintenance with rituximab. At

the same way, there are no clear data to support an advantage of

maintenance with rituximab after bendamustine-based treatment. The

MAINTAIN trial compared the results of observation only vs. 2 years vs.

4 years rituximab maintenance in patients with FL in remission after BR

induction therapy but failed to demonstrate any differences between the

different strategies.[53] In conclusion, the efficacy of rituximab

maintenance depends on the clinical contexts and induction therapy.[54]An

assessment of the prognostic value of minimal residual disease

(MRD)[20] in patients enrolled in ML17638 trial was done. MRD for the

bcl-2/IgH translocation was determined on bone marrow cells in a

centralized laboratory belonging to the Euro-MRD consortium, using

qualitative and quantitative polymerase chain reactions (PCRs). Of 234

enrolled patients, 227 (97%) were screened at diagnosis. A molecular

marker (MM) was found in 51%. Patients with an MM were monitored at 8

subsequent times. Conversion to PCR negativity predicted better

progression-free survival (PFS) at all post-treatment times (eg, end of

therapy: 3-year PFS, 72% vs 39%; P <.007). MRD was predictive in

both maintenance (83% vs 60%; P <.007) and observation (71% vs 50%;

P <.001) groups. PCR positivity at the end of induction was an

independent adverse predictor (hazard ratio, 3.1; 95% confidence

interval, 1.36-7.07). MRD is one of the most powerful independent

outcome predictor in FL patients who receive rituximab-intensive

programs, suggesting a need to investigate its value for

decision-making, also in an older population.On

the behalf of FIL, based on favorable safety and efficacy profile of

Bendamustine and on the results of the ML17638 trial, another study

(FLE09 trial) was designed to evaluate the efficacy and the safety

profile of a treatment with a combination scheme with rituximab plus

bendamustine and mitoxantrone for 4 courses, followed by a

consolidation with 4 additional doses of weekly rituximab, in elderly

FL patients, extending the upper limit of age to 80 years. Preliminary

data from this study are promising, and the publication of the final

results of the trial is ongoing. Recommendations

of the Authors: Since relapse is a common event in FL, even in patients

achieved complete remission after first-line therapy, maintenance or

consolidation therapy is needed. Maintenance

with rituximab for 2 years seems to be an effective strategy and should

also be administered in elderly patients. However, the efficacy of

rituximab maintenance depends on the clinical contexts and induction

therapy used. Second-Line Therapy and New Drugs

At

relapse of disease, it is strongly recommended to obtain a new biopsy

to exclude any transformation into an aggressive lymphoma. Targeting

the biopsy with a PET scanning may be useful.As at first presentation, observation is an accepted approach in asymptomatic patients with low tumor burden.Selection

of salvage treatment depends on the efficacy of prior regimens. In

early relapse occur (<12-24 months), a non-cross-resistant scheme

should be preferred (e.g. bendamustine after CHOP or vice versa). Other

options, including fludarabine-based, platinum salts-based or

alkylating agents-based regimens, could also be useful, but not

applicable in older or unfit patients. Rituximab

should be added if the previous anti-CD20 antibody-containing scheme

achieved >6-12-month duration of remission, while in

rituximab-refractory cases, the recently introduced new anti-CD20

antibodies of the second generation, such as obinutuzumab, demonstrated

to improve PFS in comparison to chemotherapy alone.[55]The

results of the randomized phase III GADOLIN trial that compared the

results of bendamustine alone vs obinutuzumab in association to

bendamustine in relapsed/refractory setting in indolent lymphomas have

recently been published.[55] 396 patients were enrolled: after a median

follow-up of 21.9 months, the PFS was significantly longer with

obinutuzumab plus bendamustine (median not reached [95% CI 22·5

months–not estimable]) than with bendamustine monotherapy (14·9 months

[12·8–16·6]; hazard ratio 0·55 [95% CI 0·40–0·74]; p=0·0001). Grade 3–5

adverse events occurred in 132 (68%) of 194 patients in the

obinutuzumab plus bendamustine group and in 123 (62%) of 198 patients

in the bendamustine monotherapy group. This treatment showed to be

manageable also in older patients, with acceptable safety profile.

Another study that investigated the role of obinutuzumab in association

to chemotherapy in relapsed and rituximab refractory FL is GAUDI’

trial.[56] Fifty-six patients were enrolled and were randomized to

receive obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine,

and prednisone (G-CHOP; every 3 weeks for 6 to 8 cycles) or

obinutuzumab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (G-FC; every 4 weeks

for 4 to 6 cycles). Median age was 62.5 years (range 32-75) in G-CHOP

arm vs. 61 years (range 45-77) in G-FC group. Treatment responders were

eligible for obinutuzumab maintenance every 3 months for up to 2 years.

Grade 1/2 infusion-related reactions (IRRs) were the most common

treatment-related adverse event. Neutropenia was the most common

treatment-related hematologic toxicity. Obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy

resulted in 93% to 96% response rates, with manageable toxicity also in

older people, supporting the need for a phase-3 investigation.Also,

radioimmunotherapy may represent an effective therapeutic approach, in

particular in elderly patients with comorbidities not appropriate for

high dose chemotherapy. Pisani et al.[57] published the results of a

retrospective study that investigated the long-term efficacy and safety

of a fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) regimen followed

by 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation for the treatment of nine

patients (median age 63 years, range 46–77), with grades 1 and 2

relapsed FL. After FCR, 7 patients obtained CR and 2 PR; after 90Y-RIT

2 patients in PR converted to CR 12 weeks later. With a median

follow-up of 88 months (range 13–104) since 90Y-RIT 3 deaths were not

related to lymphoma; all 3 deceased patients obtained CR before 90Y-RIT

and died still in CR. The median OS and PFS have not been reached. The

most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were hematologic. The authors

concluded that these results confirm the long-term efficacy and safety

of 4 cycles of FCR followed by 90Y-RIT in relapsed grades 1 and 2 FL.

They suggest that this regimen could be a therapeutic option for this

setting of patients, especially at the age of 60–75, who cannot receive

high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant, with no

unexpected toxicities.In

further relapses, a lot of novel drugs may play a role in monotherapy

or in association to other chemotherapy. These new molecules represent

an available strategy also in older adults, who are not eligible for

high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant programs.

Idelalisib,

a phosphatydil-inositol-3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, has been registered

in double-refractory FL, based on a phase II study, showing on ORR of

54% in this setting of patients.[58] New trials with idelalisib in

association to rituximab are ongoing.Immunomodulatory

drugs, such as Lenalidomide, in monotherapy or in association to

chemotherapy or monoclonal antibody such as rituximab, demonstrated

additional inhibition of the B-cell signaling pathway and had proved

activity in phase II studies, but randomized phase III trial are needed

to confirm these data. Fowler

et al.[59] presented the results of a phase 2 trial to assess the

efficacy and safety of lenalidomide plus rituximab (R2) in patients

with untreated, advanced stage indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A total

of 110 patients were enrolled, among that 50 FL (whose median age is

relatively young: 56 years, range 35-84). ORR for all patients was 90%

(95% CI 83–95), with 63% of CR (95% CI 53–72). Of 46 evaluable patients

with FL 87% achieved CR. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events

were neutropenia (35%).This study suggested that lenalidomide plus

rituximab is well tolerated and highly active as initial treatment for

indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and it could be applied in elderly

patients not eligible for chemotherapy regimen. An international phase

3 study (RELEVANCE trial) comparing this regimen with chemotherapy in

patients with untreated follicular lymphoma is ongoing.In

relapsed/refractory setting, Leonard et al.[60] presenting the results

of a randomized phase II trial on 91 patients affected by previously

treated FL, whose median age was 63 years (range 34-89). Patients were

randomized to receive rituximab (375 mg/m2

weekly for 4 weeks), lenalidomide (15 mg per day on days 1 to 21,

followed by 7 days of rest, in cycle 1 and then 20 mg per day on days 1

to 21, followed by 7 days of rest, in cycles 2 to 12), or a combination

therapy rituximab plus lenalidomide (LR). In the lenalidomide and LR

arms, grade 3 to 4 adverse events occurred in 58% and 53% of patients.

Dose-intensity exceeded 80% in both arms. ORR was 53% (CR 20%) and 76%

(CR 39%) for lenalidomide alone and LR, respectively (p=0.029). At the

median follow-up of 2.5 years, median TTP was 1.1 year for lenalidomide

alone and 2 years for LR (p=0.0023). The combination scheme LR is more

active than lenalidomide alone in recurrent FL with similar toxicity,

manageable also in elderly patients, warranting further studies.On

behalf of FIL, a randomized phase III multicenter trial to compare a

combination of rituximab and lenalidomide vs. rituximab alone as

maintenance after R-Bendamustine in relapsed/refractory FL patients

(FIL-RENOIR12) is ongoing. There are no age limits for enrollment, and

this trial is dedicated mainly to patients over the age of 65 or with

comorbidities, who cannot be eligible for high-dose therapy and

transplant. Other combinations, such as bortezomib plus rituximab, have

shown only a minor benefit compared with antibody monotherapy.Nivolumab,

a monoclonal antibody antiPD1, showed an ORR of 40% in

relapsed/refractory FL,[61] supporting the hypothesis of the important

role of immunosurveillance in disease control. Recommendations

of the Authors: In early relapsed FL, a non-cross-resistant

chemoimmunotherapy scheme should be used. In elderly and frail

patients, novel agents (such as new monoclonal antibodies, idelalisib,

lenalidomide, and nivolumab), with a good safety profile, should be

considered. Conclusion

Follicular

lymphoma is the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, typically

affects older adults, whose median age at diagnosis is 65 years. FL is

considered as an indolent but incurable disease with a median life

expectancy of approximately ten years. Randomized clinical trials have

demonstrated that the addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy

induction has improved the overall survival. Moreover, maintenance

therapy with Rituximab showed improvement of progression-free survival.

Despite advances in the treatment of FL, most FL patients remain

incurable and, in 10 years, 15% to 28% of cases will transform to an

aggressive phenotype, typically diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. New

clinical and biological prognostic factors are needed, to tailor

therapy better, above all in elderly patients not eligible for

aggressive chemotherapy. Some progress were already made with novel

agents, but further studies, especially focused on elderly follicular

lymphoma patients, with their peculiar characteristics, are needed to

define the best-tailored treatment at diagnosis and at the time of

relapse in this challenging clinical setting. References

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al: A Revised

European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: A proposal from

the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994; 84: 1361-1392.

PMid:8068936

- Shirley

MH, Sayeed S, Barnes I, Finlayson A, Ali R. Incidence of haematological

malignancies by ethnic group in England, 2001-7. Br J Haematol.

2013;163:465-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12562 PMid:24033296

- Smith

A, Howell D, Patmore R, et al. Incidence of haematological malignancy

by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research

Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1684-92. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.450 PMid:22045184 PMCid:PMC3242607

- Roulland

S, Faroudi M, Mamessier E, Sungalee S, Salles G, et al.: Early steps of

follicular lymphoma pathogenesis. Adv Immunol 111:1-46, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385991-4.00001-5 PMid:21970951

- Swerdlow

SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The updated who classification of

hematological malignancies. The 2016 revision of the World Health

Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016, Vol 127,

n 20. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569 PMid:26980727

- Cheson

BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial

evaluation, staging and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin

lymphoma - the Lugano Classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059-3068. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 PMid:25113753 PMCid:PMC4979083

- Cheson

BD. New staging and response criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and

Hodgkin lymphoma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008; 46(2):213-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2008.03.003 PMid:18619377

- Decaudin

D, Lepage E, Brousse N, Brice P, Harousseau JL, et al.: Low-grade stage

III-IV follicular lymphoma: ultivariate analysis of prognostic factors

in 484 patients - a study of the groupe dEtude des lymphomes de

lAdulte. J Clin Oncol 17:2499-2505, 1999.

PMid:10561315

- Federico M, Vitolo U,

Zinzani PL, Chisesi T, Clò V, et al.: Prognosis of follicular lymphoma:

A predictive model based on a retrospective analysis of 987 cases.

Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Blood 95:783-789, 2000.

PMid:10648386

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P,

Colombat P, White J, Armitage JO, et al.: Follicular lymphoma

international prognostic index. Blood. 104:1258-1265, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434 PMid:15126323

- Federico

M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al.:

Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic

index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular

lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol 27:4555-4562, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3991 PMid:19652063

- Pastore

A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R, et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk

prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy

for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective

clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet

Oncol 2015 16:1111-1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2

- Goss PE: Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in elderly patients. Leuk Lymphoma132, 993;(10):147-156.

- Ballester

OF, Moscinski L, Spiers A, et al: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the older

person: A review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; (41): 1245-1254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07310.x PMid:7693787

- Vose

JM, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD, et al: The importance of age in

survival of patients treated with chemotherapy for aggressive

non-Hodgkins lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 1988; (6): 1838-1844.

PMid:2462026

- Extermann M1, Overcash

J, Lyman GH, et al. Comorbidity and functional status are independent

in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1998(16): 1582-1587.

PMid:9552069

- Taskinen M,

Karjalainen-Lindsberg M-L, Nyman H, Eerola L-M, Leppä S: A high

tumor-associated macrophage content predicts favorable outcome in

follicular lymphoma patients treated with rituximab and

cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine- prednisone. Clin Cancer Res

13:5784-5789, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0778 PMid:17908969

- Farinha

P, Masoudi H, Skinnider BF, Shumansky K, Spinelli JJ, et al.: Analysis

of multiple biomarkers shows that lymphomaassociated macrophage (LAM)

content is an independent predictor of survival in follicular lymphoma

(FL). Blood 106:2169- 2174, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-04-1565 PMid:15933054

- Takumi

Sugimoto* and Takashi Watanabe. Follicular Lymphoma: The Role of the

Tumor microenvironment in Prognosis. J Clin Exp Hematop Vol. 56, No. 1,

June 2016.

- Ladetto M, Lobetti-Bodoni C, Mantoan B, et

al. Persistence of minimal residual disease in bone marrow predicts

outcome in follicular lymphomas treated with a rituximab-intensive

program. Blood 2013 (122)23: 3759-3766. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-507319 PMid:24085766

- Extermann M, et al. Studies of comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with cancer. Cancer Control; 2003 (10): 465-468.

- Ferrucci L. et al: The frailty syndrome: a critical issue in geriatric oncology. Critb Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003; (46): 127-137.

- Katz

S. et al. Studies of illness in the age. The index of ADL: a

standardised measure of biological and psychological functions. JAMA

1963(185): 914-919. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 PMid:14044222

- Lawton

M.P, Brody E.M: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and

instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist (1969)9:

179-186. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 PMid:5349366

- Folstein

M.F. et al: Mini Mental State: a practical method for grading the

cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psichiatr Res 1975;

(12): 189-198.

- Hickie C. e Snowdon J. Depression scales for the elderly: GDS. Clin gerontol 1987; (6): 51-53.

- Tucci

A , F errari S , B ottelli C , e t a l. A comprehensive geriatric

assessment is more eff ective than clinical judgment to identify

elderly diff use large cell lymphoma patients who benefi t from

aggressive therapy. Cancer 2009; 115: 4547- 4553. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24490 PMid:19562776

- Tucci

A, Martelli M. Rigacci L, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment is

an essential tool to support treatment decisions in elderly patients

with diff use large B-cell lymphoma: a prospective multicenter

evaluation in 173 patients by the Lymphoma Italian Foundation

(FIL). Leuk Lymphoma. 2015 Apr;56(4):921-6. doi:

10.3109/10428194.2014.953142

- Fisher

RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW, et al.: New treatment options have changed the

survival of patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;

(23):8447- 8452. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1674 PMid:16230674

- Mac

Manus MP, Hoppe RT. Is radiotherapy curative for stage I and II

low-grade follicular lymphoma? Results of a long-term follow-up study

of patients treated at Stanford University. Journal of Clinical

Oncology, 1996, 14.4: 1282-1290. PMid:8648385

- Pugh

TJ, Ballonoff A, Newman F, et al. Improved survival in patients with

early stage low-grade follicular lymphoma treated with radiation: a

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. Cancer.

2010;116:3843-3851. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25149. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25149

- Hoskin

PJ, Kirkwood AA, Popova B et al. 4 Gy versus 24 Gy radiotherapy for

patients with indolent lymphoma (FORT): a randomised phase 3

non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 457-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70036-1

- Advani

R, Rosenberg SA, Horning SJ. Stage I and II follicular non-Hodgkins

lymphoma: long-term follow-up of no initial therapy. J Clin Oncol

2004;22(8):1454-1459 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.10.086 PMid:15024027

- Brice

P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden

follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy,

prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe

dEtude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe dEtude des Lymphomes de

lAdulte. J Clin Oncol 1997;15(3):1110-1117

PMid:9060552

- Solal-Céligny P, Bellei

M, Marcheselli L et al. Watchful waiting in low-tumor burden follicular

lymphoma in the rituximab era: results of an F2-study database. J Clin

Oncol 2012; 30: 3848-3853. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4474 PMid:23008294

- Brad S. Kahl, David T. Yang. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood 2016 127:2055-2063;. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-624288

- Hiddemann

W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added

to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and

prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with

advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP

alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German

Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005;106(12):3725-3732. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016 PMid:16123223

- Bachy

E, Houot R, Morschhauser F, et al; Groupe dEtude des Lymphomes de

lAdulte (GELA). Long-term follow up of the FL2000 study comparing

CHVP-interferon to CHVP-interferon plus rituximab in follicular

lymphoma. Haematologica 2013;98(7):1107-111. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.082412 PMid:23645690 PMCid:PMC3696615

- Federico

M, Luminari S, Dondi A, et al. R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the

initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma:

results of the FOLL05 trial conducted by the Fondazione Italiana

Linfomi [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol.

2014;32(10):1095]. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(12):1506-1513 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0866 PMid:23530110

- Rummel

MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al; Study group indolent Lymphomas

(StiL). Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as

first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell

lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3

non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;381(9873):1203-1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2

- Flinn

IW et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in

first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood,

2014, 123.19: 2944-2952. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-11-531327 PMid:24591201 PMCid:PMC4260975

- Ibatici

A et al. Safety and efficacy of 90Yttrium-Ibritumomab-Tiuxetan for

untreated follicular lymphoma patients. An Italian cooperative study.

British journal of haematology, 2014, 164.5: 710-716. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12695 PMid:24344981

- Seymour

JF, Feugier P, Offner F, et al. Updated 6 Year Follow-Up Of The PRIMA

Study Confirms The Benefit Of 2-Year Rituximab Maintenance In

Follicular Lymphoma Patients Responding To Frontline

Immunochemotherapy. Blood 2013;122: abstr. 509

- Taverna

CJ, Martinell G, Hitz F, et al. Rituximab maintenance treatment for a

maximum of 5 years in follicular lymphoma: results of the randomized

phase III trial SAKK 35/03. ASH 2013; 122: abstr. 508.

- Morschhauser

F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. 90Yttrium-ibritumomab-tiuxetan

consolidation of first remission in advanced-stage follicular

non-Hodgkin lymphoma: updated results after a median follow up of 7.3

years from the international, randomized, phase III first-line indolent

trial. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31:1977-1983. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6400 PMid:23547079

- Lopez-Guillermo

A, Canales MA, Dlouhy I, et al. A randomized phase II study comparing

consolidation with a single dose of 90Y ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin)

(Z) vs. maintenance with rituximab (R) for two years in patients with

newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma (FL) responding to R-CHOP.

Preliminary results at 36 months from randomization. ASH 2013; 122:

abstr. 369.

- Vitolo U, Ladetto M, Boccomini C et al:

Rituximab maintenance compared with observation after brief first-line

R-FND chemoimmunotherapy with rituximab consolidation in patients age

older than 60 years with advanced follicular lymphoma: a phase III

randomized study by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi, J Clin Oncol 2013;

31(27):3351-9 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8290 PMid:23960180

- McLaughlin

P, Hagemeister FB, Rodriguez MA, et al.: Safety of fludarabine,

mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone combined with rituximab in the

treatment of stage IV indolent lymphoma. Semin Oncol 27:37-41, 2000.

PMid:11225999

- van Oers MH: Rituximab maintenance therapy: a step forward in follicular lymphoma. Haematologica 92:826-833, 2007. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10894 PMid:17550856

- Forstpointner

R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al.: Maintenance therapy with rituximab

leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage

therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide,

and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory

follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective

randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG).

Blood 108:4003-4008, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725 PMid:16946304

- van

Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE, et al.: Rituximab maintenance improves

clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma

in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results

of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood

108:3295-3301, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-05-021113 PMid:16873669

- Van

Oers MH, van GM, Giurgea L, et al.: Rituximab maintenance treatment of

relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: long-term outcome

of the EORTC 20981 phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol

28:2853-2858, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5827 PMid:20439641 PMCid:PMC2903319

- Rummel

MJ, Viardot A, Greil R, et al. Bendamustine Plus Rituximab Followed By

Rituximab Maintenance for Patients with Untreated Advanced Follicular

Lymphomas. Results from the StiL NHL 7-2008 Trial (MAINTAIN trial).

Blood 2014 124:3052.

- Jacobson CA and Freedman AS. One

Size Does Not Fit All in Follicular Lymphoma. Journal of Clinical

Oncology, Vol 31, No 27 (September 20), 2013: pp 3307-3308. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.0454 PMid:23960176

- Sehn

LH, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus

bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent

non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label,

multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Jun 23.

- John

Radford, Andrew Davies, Guillaume Cartron, et al. Obinutuzumab

(GA101) plus CHOP or FC in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma:

results of the GAUDI study BO21000). Blood. 2013 Aug 15;122(7):1137-43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-481341

- Francesco Pisani, Rosa Sciuto, Maria Laura

Dessanti. Long term efficacy and safety of Fludarabine,

Cyclophosphamide and Rituximab regimen followed by 90Y-ibritumomab

tiuxetan consolidation for the treatment of relapsed grades 1 and 2

follicular lymphoma. Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2015) 4:17

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-015-0012-3 PMid:26120498 PMCid:PMC4482187

- Gopal

AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S, et al. PI3Kd inhibition by idelalisib in

patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:

1008-1018. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1314583 PMid:24450858 PMCid:PMC4039496

- Nathan

H Fowler, R Eric Davis, Seema Rawal . Safety and activity of

lenalidomide and rituximab in untreated indolent lymphoma: an

open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1311-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70455-3

- John

P. Leonard, Sin-Ho Jung, Jeffrey Johnson, et al. Randomized Trial of

Lenalidomide Alone Versus Lenalidomide Plus Rituximab in Patients With

Recurrent Follicular Lymphoma: CALGB 50401 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol

2015; 33:3635-3640. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.9258 PMid:26304886 PMCid:PMC4622102

- Lesokhin

AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, et al. Preliminary results of a phase I study

of nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoid

malignancies. ASH 2014, abs 291. PMid:26827906

[TOP]