Giuseppe Gritti1, Chiara Pavoni1 and Alessandro Rambaldi1,2

1 Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit, Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy

2 Department of Oncology and Oncohematology, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

Corresponding

author: Prof. Alessandro Rambaldi, MD. Università degli Studi di

Milano, Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit, Ospedale Papa

Giovanni XXIII, Piazza OMS, 1, 24127 Bergamo, Italy. Tel.:

+39-0352673684, Fax: +39-0352674968. E-mail:

arambaldi@asst-pg23.it

Published: January 1, 2017

Received: November 11, 2016

Accepted: November 24, 2016

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017010 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.010

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

After

25 years, evaluation of minimal residual disease (MRD) in follicular

lymphoma (FL) has become a standardized technique frequently integrated

into clinical trials for its consistent and independent prognostic

significance. Achievement of a sustained MRD negativity is a marker of

treatment sensibility that has been associated with excellent clinical

outcome in terms of clinical response and progression-free survival,

independently from the employed therapy. However, no survival

advantages have been reported for MRD negative patients and despite the

compelling results of clinical trials, MRD evaluation has currently no

role in clinical practice. Ongoing clinical trials will help in

clarifying the potential setting in which MRD monitoring may have a

routine clinical application i.e. allowing de-escalation of standard

maintenance therapy in very low risk patients. In this review the

clinical implications of MRD monitoring in Rituximab-era are discussed

in light of the current treatment paradigms most aimed at reducing

toxicities, and the response definition that now routinely integrates

PET scan.

|

Introduction

Follicular

lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL),

accounting for 20-30% of all NHL in Western countries.[1]

It is characterized by a chronic course, with a projected survival of

more than 18 years in the modern chemo-immunotherapy era.[2]

While some patients with limited stage disease may be cured, those

presenting with advance stage or relapsing after local radiotherapy are

generally considered not curable with standard treatments.[1]

Early studies have shown that deferring treatment in asymptomatic

patients with low tumor burden is not associated to a worse survival

and, in many cases, the disease can remain stable for several years.[3,4] The usefulness of watchful waiting has been later on confirmed in the Rituximab era.[5]

Thus only patients bearing a high tumor burden disease and/or

symptomatic are currently treated with chemo-immunotherapy. Standard,

first line treatment includes the use of Rituximab plus chemotherapy

with an expected overall response rates of more than 90% and complete

remissions in the range of 25–70% with median progression-free survival

(PFS) exceeding 4 years.[6] A two years maintenance

with Rituximab in responders results in significant prolongation of

PFS, but not overall survival (OS).[7,8] Therefore,

despite the excellent improvement gained by chemo-immunotherapy, the

majority of the patients eventually progress or relapse.

Several

factors have been identified as of key importance in predicting PFS and

OS, among those the quality of first line response have been shown to

be remarkably associated to survival outcomes.[9]

Traditionally, response evaluation in FL has been made with the use of

contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT)-scan and bone marrow biopsy

(BMB) along with standard laboratory tests and clinical parameters.[10,11]

Immunohistochemical staining of BMB is the standard technique to assess

lymphoma infiltration, but more sensitive assays have been developed to

detect subclinical involvement. The presence of a hybrid BCL2/IGH gene

in 80-90% of FL has spurred the interest in applying polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) techniques to test the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral

blood (PB) of patients before and after treatment.[12,13]

In the current review we will discuss the methodological aspects of

molecular monitoring and its clinical significance in the modern

chemo-immunotherapy era.

Technical Aspects

The

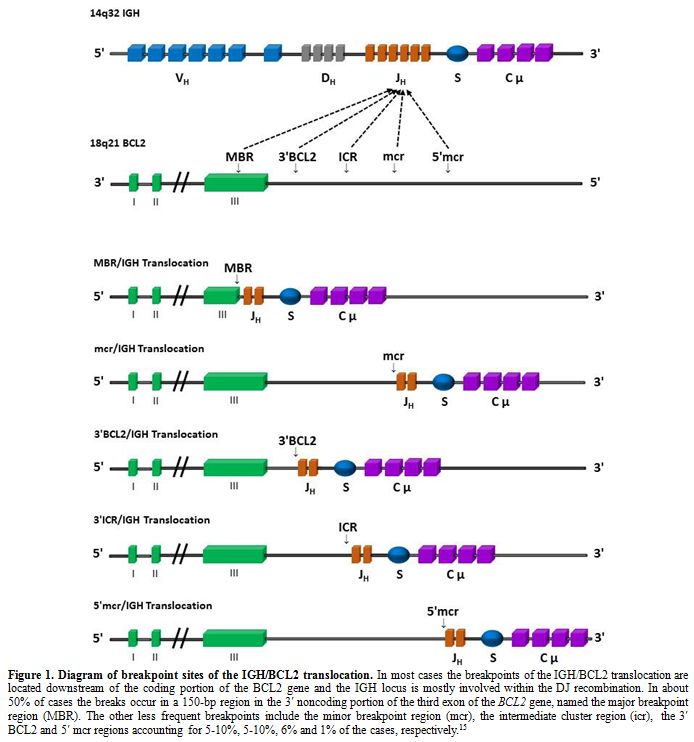

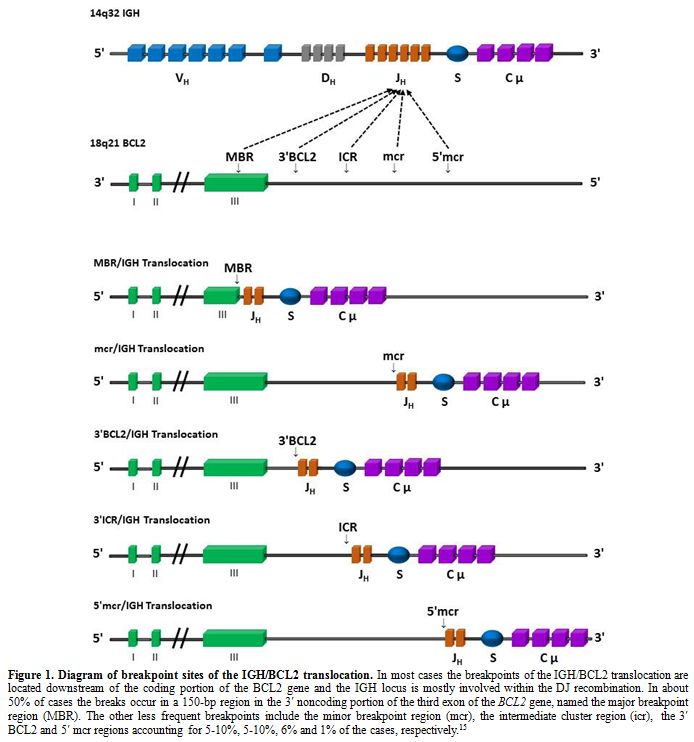

genetic hallmark of FL is the t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation that

leads to deregulated expression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2 in

tumor cells, thus allowing for the acquisition of secondary chromosomal

alterations in the germinal center environment, where the most

non-neoplastic B cells undergo apoptosis.[14] The

resulting hybrid gene BCL2/IGH is highly attractive for PCR based

assays as it is a disease specific clonal sequence directly linked to

FL pathogenesis and thus represents a highly stable marker. Five

different clusters of BCL2/IGH rearrangements occur: the major

breakpoint region (MBR), the minor clustering region (mcr), the

intermediate cluster region (ICR), the 3′-BCL-2 region and the 5′-mcr

region (Figure 1).[15]

To date, the molecular detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) has

been almost entirely based only on the study of MBR and mcr which

account for about 50 and 10% of all BCL2 rearrangements, respectively.[15]

Qualitative (nested) PCR (nPCR) has been widely used in molecular

testing FL patients and proved as a highly reproducible method with an

excellent sensitivity level able to detect 1 neoplastic cell in about a

hundred thousand normal cells (1x10-5).[16]

The advent of TaqMan-based approaches allowed the introduction of

quantitative PCR methods i.e. real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR), a

significant step forward from the mere presence or absence of a

BCL2/IGH rearrangement.[17,18] This latter technique

made possible the quantification of BCL2/IGH tumor burden at diagnosis

and the dynamic of its reduction with treatment with lower risk of

contamination and higher inter-laboratory reproducibility. Conversely,

RQ-PCR has lower sensitivity than nPCR, probably as less amount of DNA

is tested, and it is more expensive and technically complex needing the

construction of standard reference curves.[19]

|

Figure 1. Diagram of

breakpoint sites of the IGH/BCL2 translocation. In most cases the

breakpoints of the IGH/BCL2 translocation are located downstream of the

coding portion of the BCL2 gene and the IGH locus is mostly involved

within the DJ recombination. In about 50% of cases the breaks occur in

a 150-bp region in the 3′ noncoding portion of the third exon of the

BCL2 gene, named the major breakpoint region (MBR). The other less

frequent breakpoints include the minor breakpoint region (mcr), the

intermediate cluster region (icr), the 3′ BCL2 and 5′ mcr regions

accounting for 5-10%, 5-10%, 6% and 1% of the cases, respectively.[15] |

The occurrence of

non-neoplastic BCL2/IGH rearrangements in the peripheral blood of

healthy donors or patients without lymphoma was regarded as a possible

confounder factor for MRD studies.[20,21] The low

chimeric gene levels found in non-FL patients and its clearance after

chemotherapy, however, confirmed the feasibility of MRD testing in this

setting.[22] Another key point for the diffusion of

MRD assessment is standardization of methodologies and definitions of

common MRD terms. Standardization of RQ-PCR, including data

interpretation and reporting, has been made by the efforts of the

European network project EURO-MRD and has been applied in clinical

trials.[19,23-26] New technical

approaches could in the near future improve the frequency and the

feasibility of BCL2/IGH rearrangements identification, as next

generation sequencing (NGS) or droplet digital PCR.[27,28] Clinical Implication of Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring

Twenty-five

years have passed since the first observations that MRD negativity

plays a role in predicting the outcome of patients with FL.[13]

Early studies showed that standard chemotherapy programs can achieve a

molecular remission (MR) in a minority of patients. First line

anthracycline containing protocols could attain a MR in about 30-50% of

the patients,[29,30] while intensification with autologous stem-cell transplant (SCT) can lead up to 60-70% of MRD negativity.[31] Conversely, the proportion was negligible in those with relapsed disease.[32]

In all of these studies, patients achieving a MR were characterized by

a significantly prolonged disease control. Notably, long term results

of two trials aiming at reducing neoplastic cell contamination before

ASCT with ex vivo purging, confirmed that persistence of residual

marrow involvement both at microscopic or molecular assessment were the

only significant factors for long term remission, but not for survival.[33]

The

association of Rituximab with chemotherapy dramatically improved

response rates, PFS and, most notably, OS of advanced FL patients

requiring treatment.[34,35] The ability of Rituximab

to deplete FL neoplastic cells from peripheral blood and bone marrow,

increased the rates of MR, accordingly. A clear demonstration of the

Rituximab activity on MRD was shown in a study in which only responsive

patients after CHOP therapy not achieving a MR were treated with 4

weekly infusion of Rituximab.[30] Overall, sequential

administration of CHOP followed by Rituximab resulted in complete BM

and PB molecular response in more than 70% of patients. Freedom from

recurrence at 3 years was 52-57% for those patients obtaining a durable

MR after CHOP or CHOP plus Rituximab, while it was significantly lower

(20%) for those failing to obtain or lost a MR. Residual disease

kinetic showed that most of the patients in MR after CHOP were negative

at the first interim evaluation after 3 cycles. Conversely, a delayed

maximum effect was noted after Rituximab, with 59%, 74% and 63% of the

patients in MR at week +12, +28 and +44 after treatment. This late

effect of Rituximab was observed in other trials, as well as the more

difficult clearance of MRD in the BM compared with the PB.[23,24]

Rituximab have been used as consolidation therapy after autologous SCT

in small series of patients, and proved to be safe and effective both

in increasing the quality of clinical response i.e. converting PR into

CR, as well as in achieving MR.[36,37]

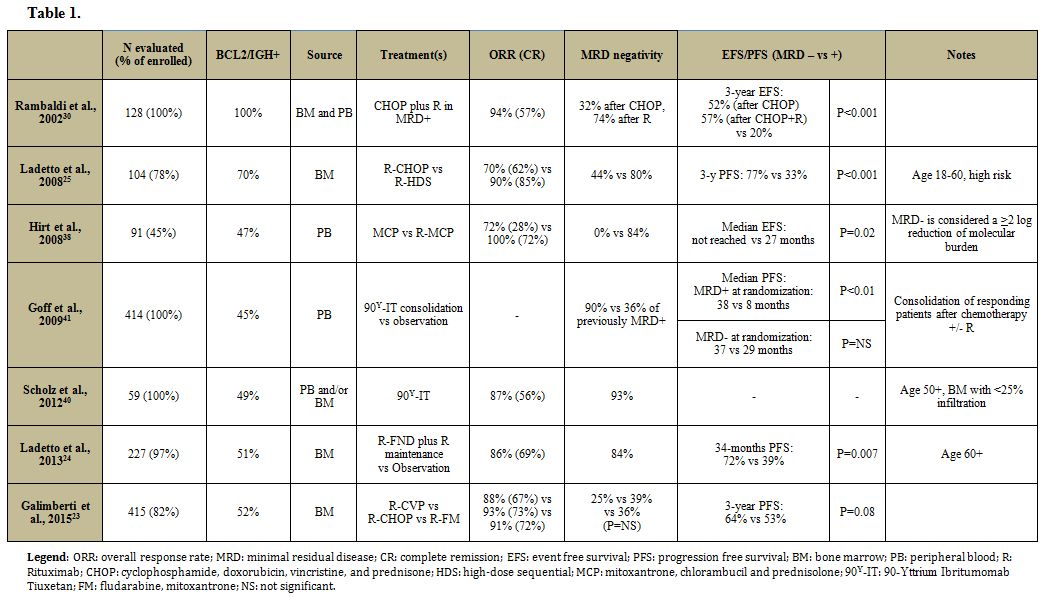

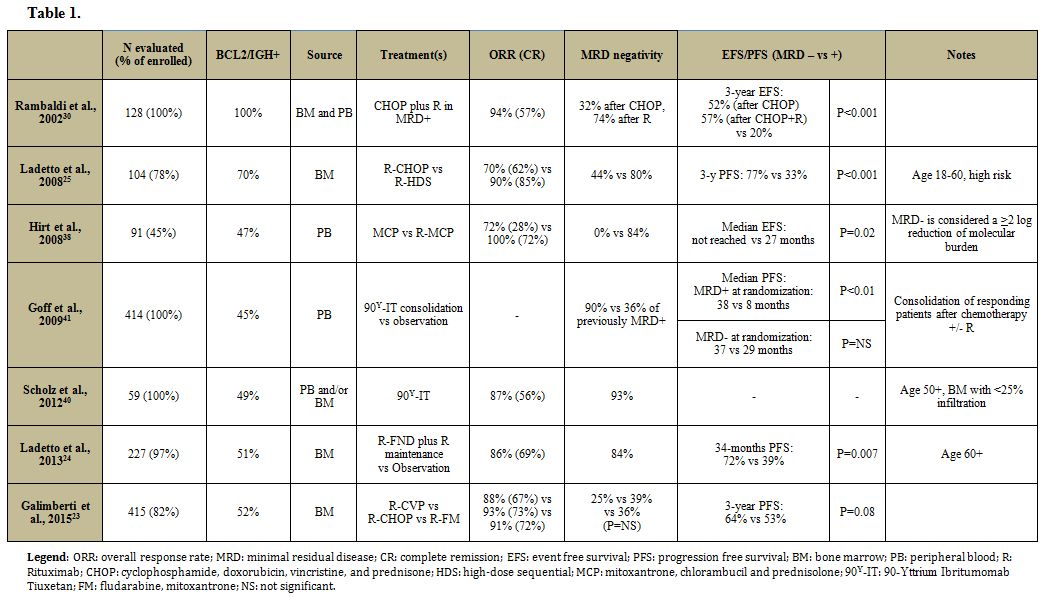

The

efficacy of front line Rituximab plus chemotherapy in inducing MR have

been included as secondary end point in several large prospective

trials (Table 1).

|

Table 1 |

In two different controlled studies, R-CHOP resulted in MR of 39-44%.[23,25]

Similar results were obtained with fludarabine and antracycline-based

induction regimens (R-FM, R-FND) and with mitoxantrone, chlorambucil,

and prednisolone (R-MCP).[23,24,38]

Indirect evidence suggests that the less intensive regimen R-CVP could

lead to inferior results both in term of clinical response and MR

rates, explaining the shorter PFS observed compared to R-CHOP/R-FM.[23]

Conversely, intensive regimens including upfront autologous SCT (R-HDS)

increase the molecular response rates up to 80% of patients.[25]

No data are currently available for the schema R-Bendamustine in the

front line setting, but Bendamustine alone or combined with the novel

anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody Obinutuzumab in relapsed/refractory

patients can induce MR.[39] Induction therapy with 90Y-Ibritumomab-Tiuxetan was associated with achievement of a MR in nearly all of the CR patients.[40]

Most importantly, all these trials confirmed the significant

improvement in disease control in terms of PFS or relapse/event free

survival in those patients achieving and maintaining the MR. The result

was independent from other prognostic factors, most importantly the

quality of response (CR vs PR), the chemotherapy induction regimen

chosen and clinical risk factors as the FL prognostic index (FLIPI).

However, the good results achieved in terms of disease control, did not

translate in survival improvement. The importance of MR was shown also

for a non-chemotherapy based consolidation. In a phase III trial

90Y-Ibritumomab-Tiuxetan was randomly given as consolidation therapy

after standard first line therapy.[41] Interestingly,

when compared to controls, consolidation with 90Y-Ibritumomab-Tiuxetan

did not improve the PFS of patients who already were in MR while a

significant prolongation of PFS was obtained in MRD positive patients

(38.4 vs 8.2 months of the control group, P<0.01). In the

relapsed/refractory setting, a randomized phase III study comparing

CHOP vs R-CHOP therapy with subsequent Rituximab maintenance vs

observation further confirmed the predictive value of MR, as almost all

of the few patients who were still BCL2/IgH PCR positive at the end of

the 2 years of maintenance treatment relapsed rapidly.[42]

Quantitative

PCR methods have been used to measure the BCL2/IGH chimeric gene burden

and early studies suggested that RQ-PCR evaluation before and after

autologous transplantation may predict the clinical course of these

patients.[43,44] In a clinical trial evaluating the

sequential administration of CHOP and Rituximab in MRD positive

patients, a high lymphoma cell burden at diagnosis was associated with

lower probability to achieve a clinical and molecular CR.[45]

The kinetic of BCL2/IGH positive cells during treatment showed that

CHOP and Rituximab were both able to remove approximately 2 logs of

tumor infiltration, thus explaining why patients with a limited

lymphoma infiltration can achieve a molecular remission after CHOP

chemotherapy alone, while the others necessitate the addition of

Rituximab. Quantification of BCL2/IGH chimeric gene burden in the BM,

but not in PB, was associated to a better event free survival. The

result of the MRD analysis of a large phase III study confirmed the

prognostic value of the molecular tumor burden both in term of

likelihood to achieve a CR, and PFS.[23] Of note,

high lymphoma cell burden at diagnosis was independent from FLIPI and

clinical response in determining PFS. The importance of RQ-PCR was

additionally shown in a study in which significant reduction (>2

logs) of circulating lymphoma cells rather than the mere MRD negativity

was associated with a favorable clinical response and prolonged

event-free survival.[38] However, not all the studies confirm these findings, probably due to the different induction regimen and Rituximab schedule.[24]

Current Issues and Future Perspective

Compelling

evidence indicates that MRD is a post treatment independent prognostic

factor that can be consistently used to guide subsequent consolidation

therapy in clinical trials. However a series of issues should be taken

into consideration. Firstly, in large randomized prospective trials

where molecular evaluation has been performed routinely, a molecular

marker could be detected in only 50 to 60% of the patients.[23-25]

In a large study including samples from 415 patients, a molecular

marker was present in 53% of the cases; in particular, 67.5% of

patients without BM infiltration were MRD positive, conversely 17.6% of

patients with microscopic marrow involvement at BMB were lacking the

molecular marker.[23] Several reasons could explain

this finding, mainly the presence of uncommon rearrangements and the

lack of significant marrow involvement in patients with nodal disease.[15]

Despite the availability of primers and probes for detecting rare

BCL2/IGH breakpoints will increase the cases with molecular marker, a

significant proportion of patients are eventually excluded from this

strategy. Persistence over time of MR is a major indication of

sustained remission. As MRD detection is more informative on BM,

especially in the Rituximab era, the need of multiple invasive

procedures additionally limits the feasibility of MRD monitoring over

time. Moreover, all the clinical trials reporting a prognostic

implication of MR included the evaluation of response according to the

1999 or 2007 International Working Group (IWG) criteria with the use of

the sole contrast enhanced CT-scan.[10,11] The

introduction of FDG-PET scan improved the accuracy of staging and

response assessment in FDG-avid lymphomas and is currently recommended

for the definition of response in FL.[46] Several

trials showed that concordance in CT-based and PET-based response

designation is critical especially for patients in PR or CR

unconfirmed, as PET scan is able to identify those patients with

metabolically active disease and thus can improve the predictive value

of response assessment.[47-49] To date, no data is

available regarding the integration of PET based response and MRD

evaluation. The only report in this setting is a retrospective

evaluation of a very limited proportion of patient (8%) enrolled in a

prospective trial.[50] This study suggests that PET

and MRD are not strongly correlated with each other, and thus could be

used as complementary techniques at the end of therapy to optimally

explore the nodal and bone marrow compartments, but further studies are

necessary to confirm the independent role of the two techniques.

The

current clinical significance of MRD evaluation should also be

evaluated when considering the evolving scenario of FL treatment. To

date, given the satisfactory median results of chemo-immunotherapy and

the lack of a survival impact of the chemotherapies available, the

routine selection of induction treatment is guided more from the

avoidance of unnecessary toxicity rather than the mere activity of the

regimen.[1] However, while most patients achieve

a prolonged disease control, a sizeable subset of cases remains

substantially refractory to front line treatment with a poor prognosis.[9]

Clinical scores currently available as FLIPI or FLIPI2 fail in

identifying such cases, and a growing numbers of prognostic factors

before or after treatment have been developed with this aim.[9,51-53]

Thus, definition of high risk patient and, accordingly, end points for

clinical trials are changing. Treatment results are satisfactory in low

risk patients and integration of new molecules should be made with

great caution in this group.[54] In this regard,

achievement of sustained MR could allow the de-escalation of standard

therapy in very low risk patients i.e. maintenance with Rituximab.

Conversely, high risk patients are a group for which standard treatment

need to be implemented and PFS should not represent per se the primary

end point. Efforts to consistently characterize this latter group are

ongoing and surrogate end points for survival as 2-year PFS have been

proposed.[9,51-53]

Conclusion

Although not yet integrated in clinical practice as compared to other setting such acute lymphoblastic leukemia,[55]

MRD evaluation is commonly integrated in clinical trials testing the

efficacy of new treatment protocols in FL patients. In this setting MRD

maintains its consistent and independent prognostic significance.

Achievement of MR is a marker of treatment sensibility that has been

associated with good clinical outcome in term of PFS, but not OS,

independently from the specific therapy. Some technical limitations

such as the limited coverage of the different breakpoints present in

the BCL2/IgH rearrangements will be likely overcome in the near future

by more appropriate molecular approaches.[27,28]

These laboratory improvements, most likely in combination with the new

imaging technologies currently tested by an ongoing clinical trial

(NCT02063685), will probably lead to a reappraisal of MRD evaluation in

FL patients

References

- Kahl BS, Yang DT. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127:2055-2063. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-624288 PMid:26989204

- Tan D, Horning SJ, Hoppe RT, et al.

Improvements in observed and relative survival in follicular grade 1-2

lymphoma during 4 decades: the Stanford University experience. Blood.

2013;122:981-987. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-03-491514 PMid:23777769 PMCid:PMC3739040

- Brice

P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden

follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy,

prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe

d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de

l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1110-1117. PMid:9060552

- Ardeshna

KM, Smith P, Norton A, et al. Long-term effect of a watch and wait

policy versus immediate systemic treatment for asymptomatic

advanced-stage non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet. 2003;362:516-522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14110-4

- Solal-Celigny

P, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, et al. Watchful waiting in low-tumor burden

follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era: results of an F2-study

database. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3848-3853. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4474 PMid:23008294

- Hiddemann W, Cheson BD. How we manage follicular lymphoma. Leukemia. 2014;28:1388-1395. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2014.91 PMid:24577532

- Salles

G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in

patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to

rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled

trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7

- Barta

SK, Li H, Hochster HS, et al. Randomized phase 3 study in low-grade

lymphoma comparing maintenance anti-CD20 antibody with observation

after induction therapy: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research

Group (E1496). Cancer. 2016;122:2996-3004. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30137 PMid:27351685

- Tarella

C, Gueli A, Delaini F, et al. Rate of primary refractory disease in B

and T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: correlation with long-term survival.

PLoS One. 2014;9:e106745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106745 PMid:25255081 PMCid:PMC4177839

- Cheson

BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop

to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI

Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244.

PMid:10561185

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579-586. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403 PMid:17242396

- Vaandrager

JW, Schuuring E, Raap T, Philippo K, Kleiverda K, Kluin P. Interphase

FISH detection of BCL2 rearrangement in follicular lymphoma using

breakpoint-flanking probes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:85-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(200001)27:1<85::AID-GCC11>3.0.CO;2-9

- Gribben

JG, Freedman AS, Neuberg D, et al. Immunologic purging of marrow

assessed by PCR before autologous bone marrow transplantation for

B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1525-1533. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199111283252201 PMid:1944436

- Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. Germinal centres and B cell lymphomagenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:172-184. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3814 PMid:25712152

- Weinberg

OK, Ai WZ, Mariappan MR, Shum C, Levy R, Arber DA. ''Minor'' BCL2

breakpoints in follicular lymphoma: frequency and correlation with

grade and disease presentation in 236 cases. J Mol Diagn.

2007;9:530-537. https://doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070038 PMid:17652637 PMCid:PMC1975105

- Weiss

LM, Warnke RA, Sklar J, Cleary ML. Molecular analysis of the t(14;18)

chromosomal translocation in malignant lymphomas. N Engl J Med.

1987;317:1185-1189. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198711053171904 PMid:3657890

- Holland

PM, Abramson RD, Watson R, Gelfand DH. Detection of specific polymerase

chain reaction product by utilizing the 5'----3' exonuclease activity

of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

1991;88:7276-7280. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.16.7276 PMid:1871133 PMCid:PMC52277

- Donovan

JW, Ladetto M, Zou G, et al. Immunoglobulin heavy-chain consensus

probes for real-time PCR quantification of residual disease in acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2000;95:2651-2658. PMid:10753847

- Bruggemann

M, Schrauder A, Raff T, et al. Standardized MRD quantification in

European ALL trials: proceedings of the Second International Symposium

on MRD assessment in Kiel, Germany, 18-20 September 2008. Leukemia.

2010;24:521-535. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2009.268 PMid:20033054

- Summers

KE, Goff LK, Wilson AG, Gupta RK, Lister TA, Fitzgibbon J. Frequency of

the Bcl-2/IgH rearrangement in normal individuals: implications for the

monitoring of disease in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin

Oncol. 2001;19:420-424. PMid:11208834

- Dolken

G, Dolken L, Hirt C, Fusch C, Rabkin CS, Schuler F. Age-dependent

prevalence and frequency of circulating t(14;18)-positive cells in the

peripheral blood of healthy individuals. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.

2008:44-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn005 PMid:18648002

- Ladetto

M, Drandi D, Compagno M, et al. PCR-detectable nonneoplastic Bcl-2/IgH

rearrangements are common in normal subjects and cancer patients at

diagnosis but rare in subjects treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol.

2003;21:1398-1403. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.07.070 PMid:12663733

- Galimberti

S, Luminari S, Ciabatti E, et al. Minimal residual disease after

conventional treatment significantly impacts on progression-free

survival of patients with follicular lymphoma: the FIL FOLL05 trial.

Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6398-6405. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0407 PMid:25316810

- Ladetto

M, Lobetti-Bodoni C, Mantoan B, et al. Persistence of minimal residual

disease in bone marrow predicts outcome in follicular lymphomas treated

with a rituximab-intensive program. Blood. 2013;122:3759-3766. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-507319 PMid:24085766

- Ladetto

M, De Marco F, Benedetti F, et al. Prospective, multicenter randomized

GITMO/IIL trial comparing intensive (R-HDS) versus conventional

(CHOP-R) chemoimmunotherapy in high-risk follicular lymphoma at

diagnosis: the superior disease control of R-HDS does not translate

into an overall survival advantage. Blood. 2008;111:4004-4013. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-10-116749 PMid:18239086

- van

der Velden VH, Cazzaniga G, Schrauder A, et al. Analysis of minimal

residual disease by Ig/TCR gene rearrangements: guidelines for

interpretation of real-time quantitative PCR data. Leukemia.

2007;21:604-611. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404586

- Drandi

D, Kubiczkova-Besse L, Ferrero S, et al. Minimal Residual Disease

Detection by Droplet Digital PCR in Multiple Myeloma, Mantle Cell

Lymphoma, and Follicular Lymphoma: A Comparison with Real-Time PCR. J

Mol Diagn. 2015;17:652-660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.05.007 PMid:26319783

- Kotrova

M, Muzikova K, Mejstrikova E, et al. The predictive strength of

next-generation sequencing MRD detection for relapse compared with

current methods in childhood ALL. Blood. 2015;126:1045-1047. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-07-655159 PMid:26294720 PMCid:PMC4551355

- Lopez-Guillermo

A, Cabanillas F, McLaughlin P, et al. The clinical significance of

molecular response in indolent follicular lymphomas. Blood.

1998;91:2955-2960. PMid:9531606

- Rambaldi

A, Lazzari M, Manzoni C, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease

after CHOP and rituximab in previously untreated patients with

follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:856-862. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V99.3.856 PMid:11806987

- Ladetto

M, Corradini P, Vallet S, et al. High rate of clinical and molecular

remissions in follicular lymphoma patients receiving high-dose

sequential chemotherapy and autografting at diagnosis: a multicenter,

prospective study by the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo

(GITMO). Blood. 2002;100:1559-1565. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-02-0621 PMid:12176870

- Gribben

JG, Freedman A, Woo SD, et al. All advanced stage non-Hodgkin's

lymphomas with a polymerase chain reaction amplifiable breakpoint of

bcl-2 have residual cells containing the bcl-2 rearrangement at

evaluation and after treatment. Blood. 1991;78:3275-3280.

PMid:1742487

- Brown

JR, Feng Y, Gribben JG, et al. Long-term survival after autologous bone

marrow transplantation for follicular lymphoma in first remission. Biol

Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1057-1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.012 PMid:17697968 PMCid:PMC4147857

- Hiddemann

W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added

to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and

prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with

advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP

alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German

Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106:3725-3732. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016 PMid:16123223

- Marcus

R, Imrie K, Belch A, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared

with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma.

Blood. 2005;105:1417-1423. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175 PMid:15494430

- Brugger

W, Hirsch J, Grunebach F, et al. Rituximab consolidation after

high-dose chemotherapy and autologous blood stem cell transplantation

in follicular and mantle cell lymphoma: a prospective, multicenter

phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1691-1698. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh425 PMid:15520073

- Morschhauser

F, Recher C, Milpied N, et al. A 4-weekly course of rituximab is safe

and improves tumor control for patients with minimal residual disease

persisting 3 months after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell

transplantation: results of a prospective multicenter phase II study in

patients with follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2687-2695. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds202 PMid:22767588

- Hirt

C, Schuler F, Kiefer T, et al. Rapid and sustained clearance of

circulating lymphoma cells after chemotherapy plus rituximab: clinical

significance of quantitative t(14;18) PCR monitoring in advanced stage

follicular lymphoma patients. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:631-640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07101.x PMid:18422779

- Pott

C, Belada D, Danesi N, et al. Analysis of Minimal Residual Disease in

Follicular Lymphoma Patients in Gadolin, a Phase III Study of

Obinutuzumab Plus Bendamustine Versus Bendamustine in

Relapsed/Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood.

2015;126:2015-2012-2003 2016:2028:2015

.

.

- Scholz

CW, Pinto A, Linkesch W, et al. (90)Yttrium-ibritumomab-tiuxetan as

first-line treatment for follicular lymphoma: 30 months of follow-up

data from an international multicenter phase II clinical trial. J Clin

Oncol. 2012;31:308-313. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1553 PMid:23233718

- Goff

L, Summers K, Iqbal S, et al. Quantitative PCR analysis for Bcl-2/IgH

in a phase III study of Yttrium-90 Ibritumomab Tiuxetan as

consolidation of first remission in patients with follicular lymphoma.

J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6094-6100. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6258 PMid:19858392

- van

Oers MH, Tonnissen E, Van Glabbeke M, et al. BCL-2/IgH polymerase chain

reaction status at the end of induction treatment is not predictive for

progression-free survival in relapsed/resistant follicular lymphoma:

results of a prospective randomized EORTC 20981 phase III intergroup

study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2246-2252. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0852 PMid:20368567

- Ladetto

M, Sametti S, Donovan JW, et al. A validated real-time quantitative PCR

approach shows a correlation between tumor burden and successful ex

vivo purging in follicular lymphoma patients. Exp Hematol.

2001;29:183-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00651-2

- Galimberti

S, Guerrini F, Morabito F, et al. Quantitative molecular evaluation in

autotransplant programs for follicular lymphoma: efficacy of in vivo

purging by Rituximab. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:57-63. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704102 PMid:12815479

- Rambaldi

A, Carlotti E, Oldani E, et al. Quantitative PCR of bone marrow

BCL2/IgH+ cells at diagnosis predicts treatment response and long-term

outcome in follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:3428-3433. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-06-2490 PMid:15637137

- Cheson

BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial

evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin

lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059-3068. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 PMid:25113753 PMCid:PMC4979083

- Le

Dortz L, De Guibert S, Bayat S, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic impact

of 18F-FDG PET/CT in follicular lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging.

2010;37:2307-2314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-010-1539-5 PMid:20717826

- Dupuis

J, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Julian A, et al. Impact of

[(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response

evaluation in patients with high-tumor burden follicular lymphoma

treated with immunochemotherapy: a prospective study from the Groupe

d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte and GOELAMS. J Clin Oncol.

2012;30:4317-4322. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0934 PMid:23109699

- Trotman

J, Fournier M, Lamy T, et al. Positron emission tomography-computed

tomography (PET-CT) after induction therapy is highly predictive of

patient outcome in follicular lymphoma: analysis of PET-CT in a subset

of PRIMA trial participants. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3194-3200. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0736 PMid:21747087

- Luminari

S, Galimberti S, Versari A, et al. Positron emission tomography

response and minimal residual disease impact on progression-free

survival in patients with follicular lymphoma. A subset analysis from

the FOLL05 trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Haematologica.

2016;101:e66-68. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2015.132811 PMid:26471485 PMCid:PMC4938338

- Casulo

C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma

After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and

Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From

the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2516-2522. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7534 PMid:26124482 PMCid:PMC4879714

- Pastore

A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R, et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk

prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy

for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective

clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet

Oncol. 2015;16:1111-1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2

- Jurinovic

V, Kridel R, Staiger AM, et al. Clinicogenetic risk models predict

early progression of follicular lymphoma after first-line

immunochemotherapy. Blood. 2016;128:1112-1120. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-05-717355 PMid:27418643

- Cheson BD. Speed bumps on the road to a chemotherapy-free world for lymphoma patients. Blood. 2016;128:325-330. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-04-709477 PMid:27222479

- Spinelli

O, Tosi M, Peruta B, et al. Prognostic significance and treatment

implications of minimal residual disease studies in

Philadelphia-negative adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mediterr J

Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6:e2014062. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2014.062 PMid:25237475 PMCid:PMC4165493

[TOP]

.

.