Paola Magro1, Ilaria Izzo1, Barbara Saccani1, Salvatore Casari1, Silvio Caligaris1, Lina Rachele Tomasoni1, Alberto Matteelli1, Annamaria Lombardi2, Antonella Meini2 and Francesco Castelli1

1 University

Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia

and Spedali Civili General Hospital, Brescia, Italy.

2 University Department of Pediatrics, University of Brescia and Spedali Civili General Hospital, Brescia, Italy.

Corresponding

author: Ilaria Izzo, MD. University Department of Infectious and

Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia and Spedali Civili General

Hospital, Brescia, Italy. Tel: +39303995677. E-mail:

izzo.ilaria@hotmail.it

Published: March 1, 2017

Received: December 12, 2016

Accepted: February 14, 2017

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017023 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.023

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

The

protective role of Sickle Cell Trait (SCT) in malaria endemic areas has

been proved, and prevalence of HbS gene in malaria endemic areas is

high. Splenic infarction is a well-known complication of SCT, while the

association with malaria is considered rare. A Nigerian boy was

admitted to our ward after returning from his country of origin, for P. falciparum malaria.

He underwent abdominal ultrasound for upper right abdominal pain,

showing cholecystitis and multiple splenic lesions suggestive of

abscesses. Empiric antibiotic therapy was undertaken. Bartonella, Echinococcus, Entamoeba

serologies, blood cultures, Quantiferon test, copro-parasitologic exam

were negative; endocarditis was excluded. He underwent further blood

exams and abdomen MRI, confirming the presence of signal alterations

areas, with radiographic appearance of recent post-infarction outcomes.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis showed a percentage of HbS of 40.6% and a

diagnosis of SCT was then made.

Splenic infarction should be taken

into account in patients with malaria and localized abdominal

pain. Moreover, diagnosis of SCT should be considered.

|

Case Report

In

1948 Haldane firstly hypothesized the existence of a protective

relationship between an otherwise harmful genetic mutation and a

population with a high frequency of parasite infection. Since then, the

protective role of Sickle Cell Trait (SCT) in malaria endemic areas has

been proved in several studies.[1,2] In fact, if red cells are abnormal, the chance of success of the parasite is affected, reducing death rate due to Plasmodium spp.

Splenic

infarction is a well-known complication of SCT, in particular during

exercise at high altitude, but it has also been described at rest in

aircrafts or with exercise at sea level. Splenic vaso-occlusion is

related to hemoglobin S polymerization and red cell deformation.

Clinical presentation consists of severe upper quadrants abdominal

pain, vomiting, and nausea. Fever, leukocytosis and elevation of LDH

usually occur in the first 3 days.[3]

In

contrast, malaria-associated splenic infarctions are considered rare.

Anyway, reports of single or small series of cases have appeared almost

annually.[4] Is therefore really unusual to find these three conditions co-existing?

We report the case of an 11-year-old Nigerian boy, living in Italy since 2010. On August, 26th he flew back from a one-month stay in Nigeria, and two days later he started presenting fever. On August, 31st

he complained vomiting and abdominal pain and was then conducted to the

Emergency Room of our Hospital. Here, after an initial suspect of

appendicitis, a diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum

malaria was made, and the patient was admitted to the Infectious

Diseases ward. Body temperature was 38°C, while other vital signs were

normal. His complete blood count showed leukopenia (WBC 4060, nv

4500-10800) and thrombocytopenia (PLT 59,000, nv 100,000-400,000),

while hemoglobin was 13 g/dL (nv 13-16.5 g/dL). His chemistry profile

showed hyperbilirubinemia (2.93 mg/dL, nv 0.2-0.5 mg/dL), AST 136 UI/L

and ALT 122 UI/L (nv 13-51 UI/L and 15-47 UI/L, respectively),

creatinine was 1.06 mg/dL (nv 0.3-0.9 mg/dL) and an increase of LDH

values (657 U/L) was present (nv 120-330 U/L); C-reactive protein was

85.6 mg/L (nv <5 mg/L). He started therapy with

piperachin/diidroartemisin 320/40 mg, 3 tablets qd, and as long as he

kept presenting well-localized right upper quadrant abdominal pain, an

ultrasound (US) was performed on September, 1st.

The exam showed a starred sky appearance of the liver associated with a

slightly enlarged gallbladder, with transonic content and thickened

walls, suggestive of cholecystitis. A slight increase of the spleen’s

dimensions (pole-to-pole diameter 11 cm) was present, and in its

context a hypo-anechoic, inhomogeneous ovalar lesion (diameter 1.5 cm)

was found, raising a diagnostic doubt (Abscess? Hematoma? Cyst?). The

pediatric surgeon confirmed a non-surgical approach for cholecystitis

and antibiotic therapy with piperacilline/tazobactam 4.5 g tid (body

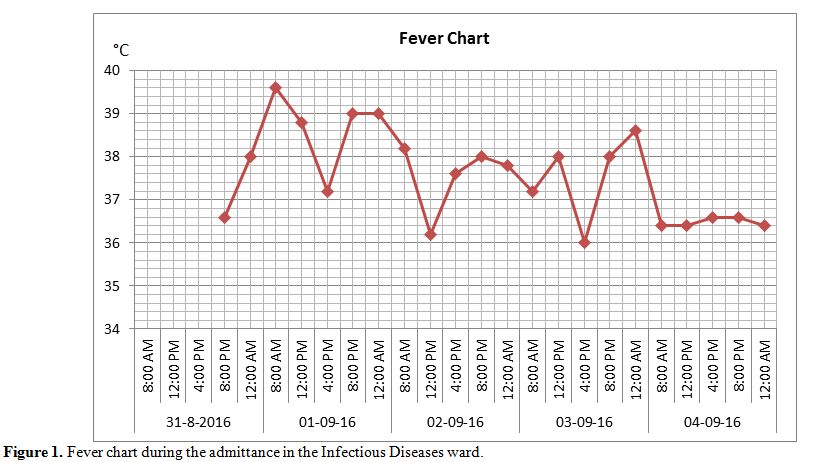

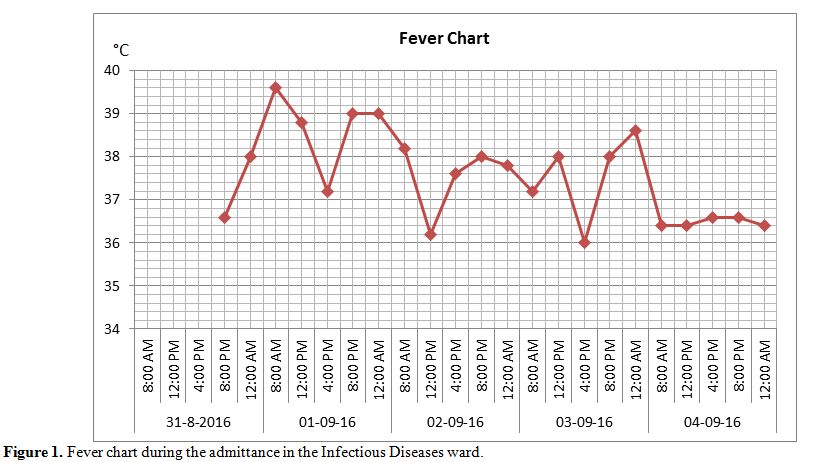

weight of 42 Kg) was undertaken. As long as he kept presenting fever (Figure 1) although therapy for malaria was considered over (piperachin/diidroartemisin 320/40 mg, 3 tablets qd, from August, 31st to September, 2nd)

and hemoscopy resulted negative, as suggested by the radiologist, the

next day the US was repeated, showing multiple splenic abscesses.

Therefore, serologies for Bartonella, Echinococcus and Entamoeba and blood cultures were sent.

|

Figure 1. Fever chart during the admittance in the Infectious Diseases ward. |

Quantiferon

test and coproparasitologic exam were executed, resulting both

negative. An echocardiogram showed no endocarditic vegetations. On

September, 5th

the boy was transferred to the Pediatrics ward for cholecystitis and

splenic abscesses. Antimicrobial spectrum was broadened with

Claritromicine 250 mg bid per os. Blood tests were performed, including

peripheral blood smear, quantitative Ig, total IgE, lymphocyte typing,

hemoglobin electrophoresis and dihydrorhodamine 123 test, in order to

evaluate any underlying hematologic diseases. On September, 8th,

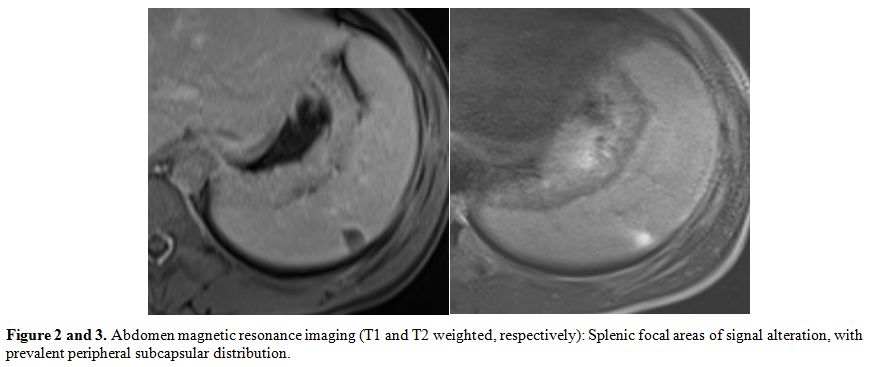

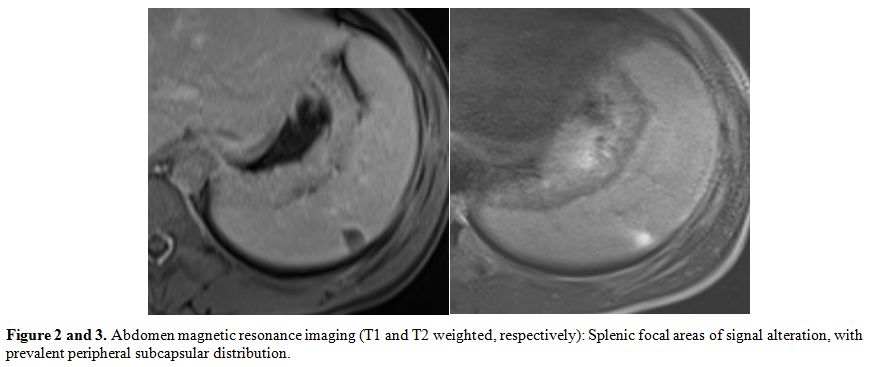

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen was performed,

confirming the presence of seven focal areas of signal alteration, with

prevalent peripheral subcapsular distribution (maximum size 1.7 mm).

The

morphology of the formations, especially of the most voluminous, was a

pyramidal wedge with the apex pointing towards the hilum, and the base

of the splenic capsule, while profiles looked finely irregular (Figure 2 and 3).The

radiographic appearance then made it less likely the possibility of

splenic abscesses, in favour of a diagnosis of recent post-infarction

outcomes or hematomas in a subacute phase. While all other requested

exams resulted negative, on September, 13th,

hemoglobin electrophoresis showed a percentage of HbS of 40.6%, HbA was

55.2% while HbA2 and HbF were respectively 3.5 and 0.7%. A diagnosis of

SCT was then made.

|

Figure 2 and 3. Abdomen magnetic resonance

imaging (T1 and T2 weighted, respectively): Splenic focal areas of

signal alteration, with prevalent peripheral subcapsular distribution. |

On September, 15th

the boy was discharged, with recommendations to radiologic follow-up

and preconception counseling for him and his parents and without

further antibiotic therapy.

On October, 13th

the boy repeated the US, which showed a normal spleen. The timing of

regression is compatible with the diagnosis of splenic infarction.

Discussion and Conclusions

SCT has a protective role in the pathogenesis of severe malaria, whereas HbS is not an absolute impediment to the infection by Plasmodium spp.

Probably an early phagocytose of the parasited sickled cells by the

reticulo-endothelial system is the mechanism for the increased fitness

of patients with SCT.[1] Prevalence of HbS gene in

malaria endemic areas can reach a percentage >20%; therefore this

diagnosis must be taken into account in a patient hailing from one of

these countries,[2] especially when anemia is present. Splenic infarction is a complication of SCT,[3]

and it has been reported at rest in aircrafts, moreover it has been

described as a rare complication of malaria, it is primarily caused by P. falciparum, occurring mostly during the acute phase of the infection,[4]

even if the exact frequency of malaria-associated splenic infarction

remains unclear because of under-diagnosis and under-reporting.[5]

In

our case, as long as fever kept on after the conclusion of an adequate

cycle of antimalarial therapy, in association with abdominal pain in

the right upper quadrant and evidence of splenic lesions, further

analysis have been undertaken in the suspect of a concomitant

condition. Trauma was excluded. Therefore we considered as differential

diagnosis splenic abscesses, both primary or secundary (e.g.

endocarditis, patent foramen ovale), splenic infarction, primary

hematologic diseases and granulomatous diseases (e.g. tuberculosis and

chronic granulomatous disorder). Contrary to our case, abdominal pain

is generally reported as localized to the left upper quadrant, when

splenic infarction is present.[4] In the reported

case, atypical clinical presentation, concomitant cholecystitis and

radiological diagnosis of splenic abscesses were misleading.

Splenic

infarction should be taken into account in a patient with malaria and

abdominal pain, particularly when localized to upper quadrants, and US

and CT scan should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Computed

tomography scan with contrast is the gold standard for diagnosis of

splenic infarction. In our case, however, US has been primarly

performed in the suspect of cholecystitis. MRI was then performed,

taking into account the young age of the patient and the good

sensitivity of this technique for spleen lesions.[5] Conservative therapy must be attempted, and the prognosis is good.[6]

Splenectomy should be reserved for those patients with severe damage to

the spleen, also taking into account possible future complications,[7] including severe malaria.

Finally,

as long as the number of international migrants worldwide kept on

growing over the past decades, all of us clinicians should be aware of

pathologies we haven’t been familiar with in our daily activity.

References

- Luzzatto L. Sickle Cell Anaemia and Malaria. Mediter J Hematol Infect Dis 2012, 4(1): e2012065. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2012.065 PMid:23170194 PMCid:PMC3499995

- Russo G et al. Italian Guidelines for the Sickle Cell Disease in Pediatrics. AIEOP. Article available at http://www.aieop.org/files/files_htmlarea/tutto%20giu12.pdf last accessed on November 12th, 2016.

- Kark J. Sickle cell trait. Article available at http://sickle.bwh.harvard.edu/sickle_trait.html, last accessed on November 12th, 2016

- Hwang JH, Lee CS. Malaria-Induced Splenic Infarction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 2014;91(6):1094–1100 https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0190 PMid:25294615 PMCid:PMC4257629

- Parikh M, Pachter L, Stewart GD. Splenic Infarct Workup. Article available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/193718-workup#c5, last accessed on January 30th, 2017

- Cinquetti

G, Banal F, Rondel C, et al. Splenic infarction during Plasmodium ovale

acute malaria: first case reported. Malar J 2010;9: 288. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-288 PMid:20955610 PMCid:PMC2984568

- Leone

G, Pizzigallo E. Bacterial infections following splenectomy for

malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Mediterr J Hematol

Infect Dis 2015, 7(1): e2015057 https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2015.057 PMid:26543526 PMCid:PMC4621170

[TOP]