Ignazio Majolino1, Dosti Othman2, Attilio Rovelli1, Dastan Hassan2, Luqman Rasool2, Michele Vacca1, Nigar Abdalrahman2, Chra Abdullah2, Zhalla Ahmed2, Dlir Ali2, Kosar Ali2, Chiara Broggi1, Cinzia Calabretta1, Marta Canesi1, Gloria Ciabatti1, Claudia Del Fante1, Elisabetta De Sapio1, Giovanna Dore1, Andrea Frigato1, Marcela Gabriel1, Francesco Ipsevich1, Harem Kareem2, Dana Karim2, Rosa Leone1, Tavan Mahmood2, Annunziata Manna1, Maria Speranza Massei1, Andrea Mastria1, Dereen Mohammed2, Rebar Mohammed2, Khoshnaw Najmaddin2, Diana Noori2, Angelo Ostuni1, Angelo Palmas1, Marco Possenti1, Ali Qadir2, Giorgio Real1, Rebwar Shrif2, Caterina Valdatta1, Stefania Vasta1, Marta Verna1, Mariangela Vittori1, Awder Yousif2, Francesco Zallio1, Alessandro Calisti1 , Sergio Quattrocchi3 and Corrado Girmenia1.

1 Institute for University Cooperation (ICU), Rome Italy.

2 Hiwa Cancer Hospital (HCH), Sulaymaniyah, Iraqi Kurdistan.

3 Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS), Rome, Italy.

Corresponding

author: Ignazio Majolino, Via Antonio Cerasi 22, 00152 Rome, Italy. Tel: +39-3381519277. E-mail:

ignazio.majolino@gmail.com

Published: April 15, 2017

Received: February 16, 2017

Accepted: March 20, 2017

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017031 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.031

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

We

describe the entire process leading to the start-up of a hematopoietic

stem cell transplantation center at the Hiwa Cancer Hospital, in the

city of Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Iraqi Region. This capacity building

project was funded by the Italian Development Cooperation Agency and

implemented with the support of the volunteer work of Italian

professionals, either physicians, nurses, biologists and technicians.

The intervention started in April 2016, was based exclusively on

training and coaching on site, that represent a significant innovative

approach, and led to a first autologous transplant in June 2016 and to

the first allogeneic transplant in October. At the time of reporting, 9

months from the initiation of the project, 18 patients have been

transplanted, 15 with an autologous and 3 with an allogeneic graft. The

center at the HCH represents the first transplantation center in

Kurdistan and the second in wide Iraq. We conclude that international

development cooperation may play an important role also in the field of

high-technology medicine, and contribute to improved local centers

capabilities through country to country scientific exchanges. The

methodology to realize this project is innovative, since HSCT experts

are brought as volunteers to the center(s) to be started, while

traditionally it is the opposite, i.e. the local professionals to be

trained are brought to the specialized center(s).

|

Introduction

Hemopoietic

stem cell transplantation (HSCT), either autologous or allogeneic, is

an effective treatment for many hematologic disorders. On a global

basis, over 70.000 procedures are currently performed every year in

more than 70 countries.[1] Unfortunately, due to

economical and/or political constraints, not all the countries and

geographical areas have enough resources and expertise to establish a

HSCT program. This implies that in many countries patients are forced

to emigrate when a transplant is needed, with heavy social and economic

problems for their families and the governments.

The Hiwa Cancer

Hospital (HCH) of Sulaymaniyah is a leading oncology institution in

Iraqi Kurdistan. In 2015, the Institute for University Cooperation

(ICU) of Rome identified this center as a possible target for a project

of high-technology medical intervention addressed to the development of

a HSCT center devoted to the treatment of malignant and non-malignant

hematologic disorders, in particular thalassemia major, which

represents a major problem in the country. A transplantation expert

from Italy made a preliminary visit to the HCH, confirming the

feasibility of a stem cell transplantation program. A capacity-building

project was designed and submitted to the Italian Development

Cooperation Agency (AICS), which approved its funding on March 2016.

Capacity

building is the process by which individuals, organizations,

institutions and societies develop abilities to perform functions,

solve problems and set and achieve objectives.[2] In

this paper we describe the entire process leading to the start-up of

the Center, the results obtained 9 months after the start of the

project and future perspectives. This is the first stem cell

transplantation center established in the Kurdistan Region, and the

second in Iraq. We conclude that international development cooperation

may be of great value in the field of high-technology medicine and

contribute to improved local centers’ capabilities, through

country-to-country scientific exchanges. Moreover, on-site training and

coaching proves an effective innovative method to establish a

sustainable activity in developing countries, as alternative to a more

traditional methodology, where local professionals to be trained are

brought to the specialized center(s) with higher expenditure and less

predictable final results.

Methods

Exploratory mission:

A relationship between the HCH and the ICU started in July 2015, when

an Italian HSCT expert conducted an exploratory mission on behalf of

ICU in order to ascertain the feasibility of a stem cell

transplantation project at the HCH. A transplantation unit (TU) with

positive pressure single rooms had been previously built in the HCH,

thanks to a donation of the Regione Toscana, Italy, but the unit was

never activated due in part to limited availability of adequate skills

and in part to economic problems.

During the first visit, an

appropriate grid, already successfully employed in other circumstances

and containing all the necessary questions, was applied to verify the

adequacy of the hospital itself and of all the necessary services that

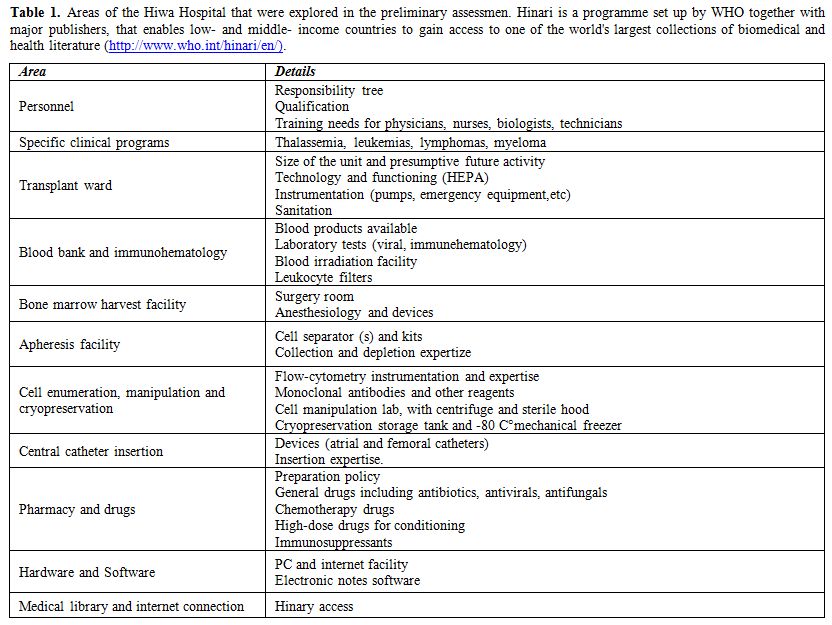

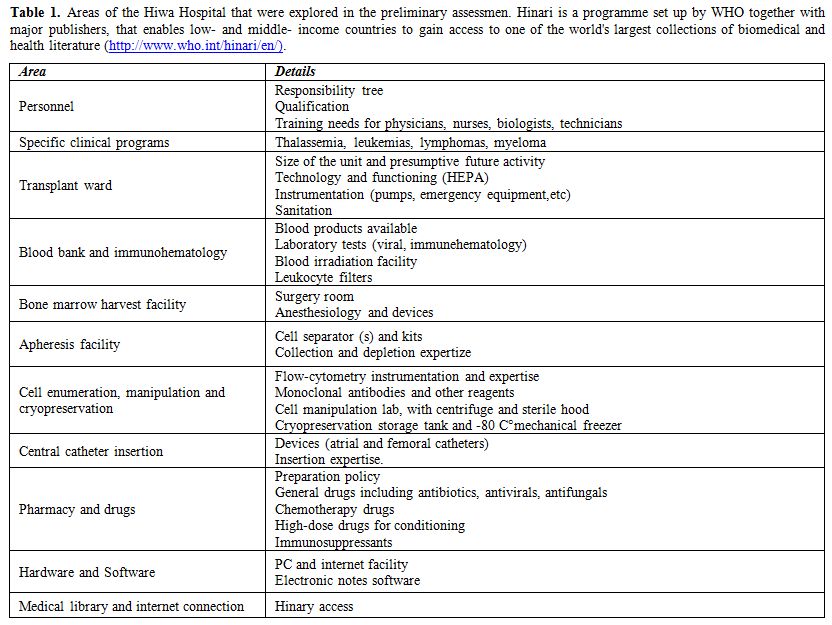

are normally involved in HSCT. The areas involved in the process were

those listed in table 1. The

director of HCH and most of the single-sector responsible physicians or

administrators were interviewed. Inspections were also conducted to

better ascertain the availability and functioning of instrumentations

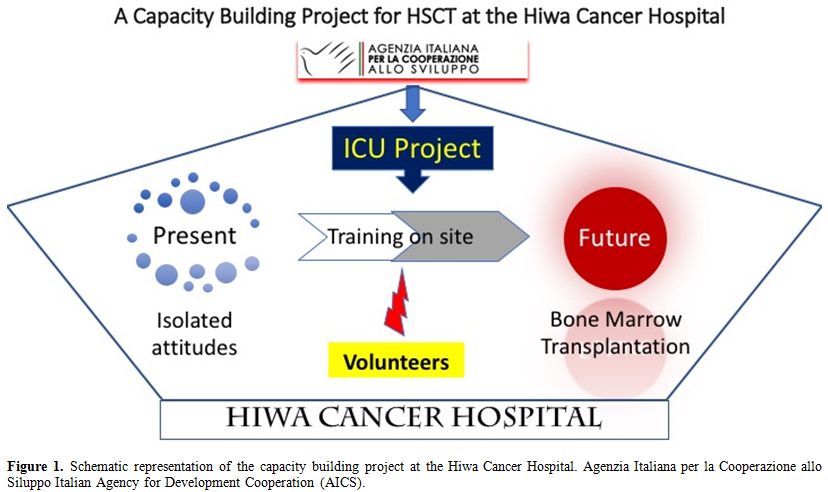

and devices. At the end of the visit, a positive evaluation was

released, confirming the feasibility of a capacity building project for

the start-up of a stem cell transplantation activity. A simplified

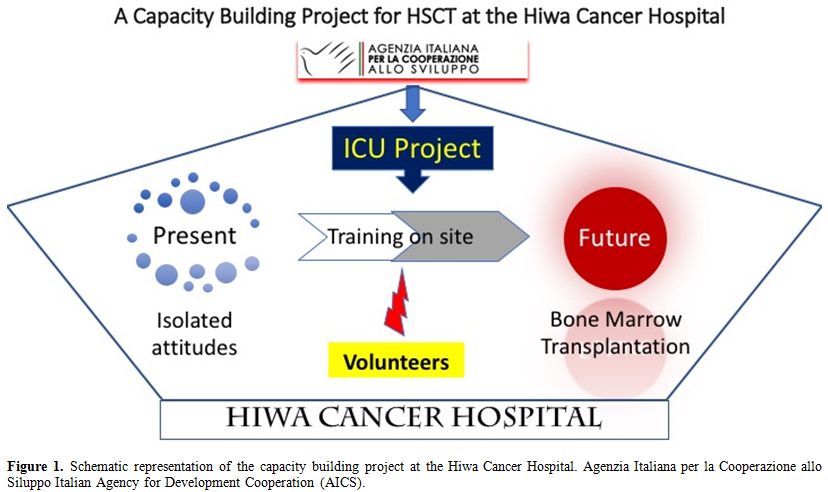

scheme of our project is shown in figure 1.

|

Table 1.

Areas of the Hiwa Hospital that were explored in the preliminary

assessmen. Hinari is a programme set up by WHO together with major

publishers, that enables low- and middle- income countries to gain

access to one of the world's largest collections of biomedical and

health literature (http://www.who.int/hinari/en/). |

|

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the

capacity building project at the Hiwa Cancer Hospital. Agenzia Italiana

per la Cooperazione allo Siluppo Italian Agency for Development

Cooperation (AICS). |

Project definition and funding:

The second step was designing the project. This was done according to a

call for proposal (n. 10548/02/0) by the Italian Ministry for Foreign

Affairs – General Direction for Development Cooperation. A capacity

building project was submitted by ICU, approved and funded in December

2015. The assigned budget was € 329,000. The contribution of HCH itself

to the financial plan consisted of existing instrumentation and

laboratory facilities, but the HCH also provided for the accommodation

of the volunteers for the whole duration of the project.

Unfortunately,

still in the month of December 2015 a fire accident suddenly developed

in the TU, due to malfunctioning of the air-treatment unit, with severe

damage to the whole TU for a cost of approx. $ 200,000. Though this

obviously represented a factor for a possible delay or even suspension

of the project, the scientific advisor of ICU and the responsible for

AICS prompted for a rapid restoration of the TU, that HCH started in

April 2016. The delay was therefore minimal, and the team could begin

the training activity the same month, while the restoration works were

ended in July.

The capacity building process:

To reach the target of a self-sustainable HSCT activity at the HCH,

efforts were directed to the training of local personnel, in particular

to perform functions, solve problems and set and achieve objectives.[2]

The scientific advisor of the project also coordinated the volunteers

who delivered training with lectures and seminars, and were also in

charge of editing and verifying protocols, as well as of steering

clinical work and coaching the local personnel. This was done by

attending the morning patient tour and the afternoon outpatient clinic,

or participating to the laboratory activities. The personnel involved

in the HSCT program, either Italian and Kurdish, also attended the

regular weekly activities, such as the morning briefings (every

working-day), the weekly seminars on clinical and scientific issues,

the transplantation meetings (once a week) with discussion of all the

transplantation cases. The chairman of the transplantation meeting

regularly took minutes that were regularly distributed to all

participants. Results

Project start-up:

In April 2016, we decided to hold the preliminary training course

addressed to doctors, nurses, biologists and technicians of the HCH.

The course took approximately 3 weeks. A list of the covered subjects

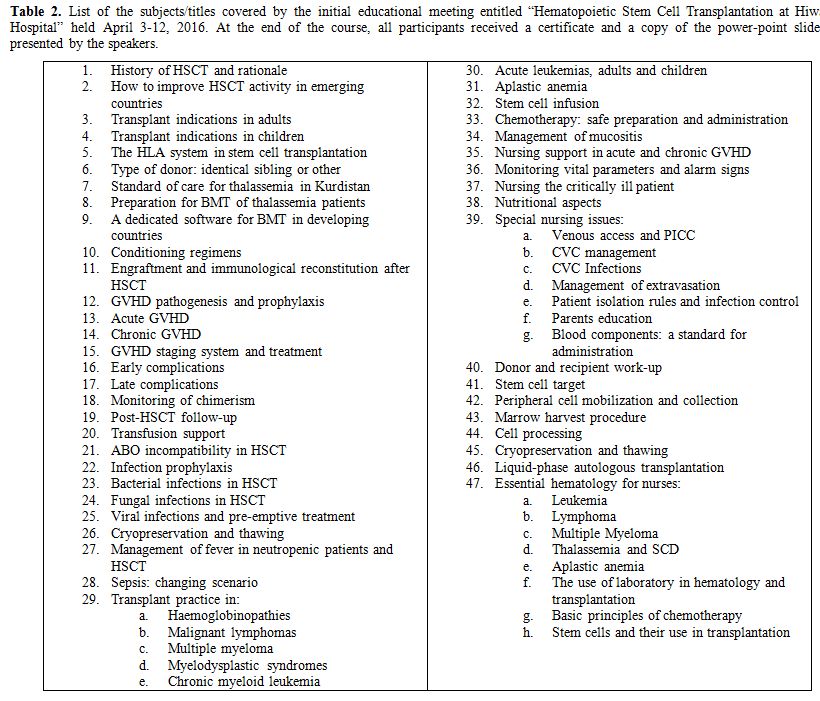

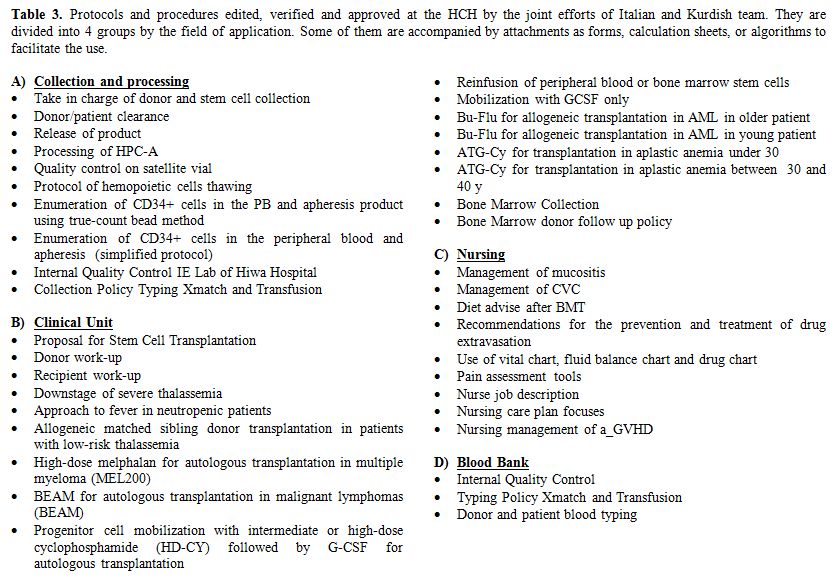

is reported in table 2. Editing and verification of clinical and laboratory protocols dedicated to the transplantation program (Table 3)

were conducted during the same period. The hospital provided the

dedicated staff, and the director also drew an organigram depicting the

responsibility tree. This led to a substantial modification of the

organization, also to cope with existing international standards, as

those defined by JACIE at http://www.jacie.org/standards.

|

Table 2.

List of the subjects/titles covered by the initial educational

meeting entitled “Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation at Hiwa

Hospital” held April 3-12, 2016. At the end of the course, all

participants received a certificate and a copy of the power-point

slides presented by the speakers. |

|

Table 3. Protocols and procedures edited,

verified and approved at the HCH by the joint efforts of Italian and

Kurdish team. They are divided into 4 groups by the field of

application. Some of them are accompanied by attachments as forms,

calculation sheets, or algorithms to facilitate the use. |

The

apheresis facility was the first to be started with 2 new-generation

cell separators, a Fresenius Comtec, and an Amicus Fenwall device. A

reliable and easy to use flow-cytometry double platform technique for

CD34+ cell enumeration was assessed, based on a well established

methodology.[3] The manipulation laboratory and a

technique for cell cryopreservation were set up by the Italian team and

implanted in the HCH. A well-equipped transplantation sterile ward,

with 6 HEPA-filtered, positive pressure, conditioned-air single rooms

was already present and ready for use. At the beginning the

cryopreservation was carried out by means of a -80°C mechanical freezer

alone,[4] but later a fully equipped liquid nitrogen

tank was supplied and cells were initially freezed in the -80°C to be

later stored in the liquid phase of liquid nitrogen.

One month

later, a series of patients underwent clinical selection procedures

based on previously approved criteria and including age, general

performance, organ function, disease phase and informed consent, and

some of them were finally admitted for the stem cell collection and

cryopreservation in view of the autologous transplantation. For stem

cell mobilization, in patients with multiple myeloma we used a protocol

with G-CSF alone (G-CSF 10 µg/kg/day

until the CD34+ cell collection target was achieved, usually day 5),

while in lymphoma patients harvest was done in the context of the

advanced disease protocol itself. This was BeGeV[5] in Hodgkin lymphoma, DHAP in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, always with addition of G-CSF 10 µg/kg/day

since the end of chemotherapy to the day when CD34+ cell collection

target was achieved. In some cases, also the intermediate-dose (2 to 4

g/m2) cyclophosphamide mobilization protocol[6,7] was employed. Since in this phase of the program only single transplants were planned, a target of 5 x 106/Kg CD34+ cells was set, using an algorithm to have an accurate collection prediction,[8]

with an intention to increase the value as soon as the preliminary

results would confirm us of the adequacy of the procedures in view of a

double autologous transplantation program.

First autologous transplants:

A first autologous transplant was carried out 3 months after the

program was started in a multiple myeloma patient, using melphalan 140

mg/m2 as high-dose regimen and

peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) as autograft. The engraftment was

prompt without major complications. The following month another myeloma

patient was successfully autografted, and the program was therefore set

out with a series of candidates either with myeloma or malignant

lymphoma. Since July, when the HSCT Unit restoration was completed, the

transplants were all carried out in the new ward. The clinical

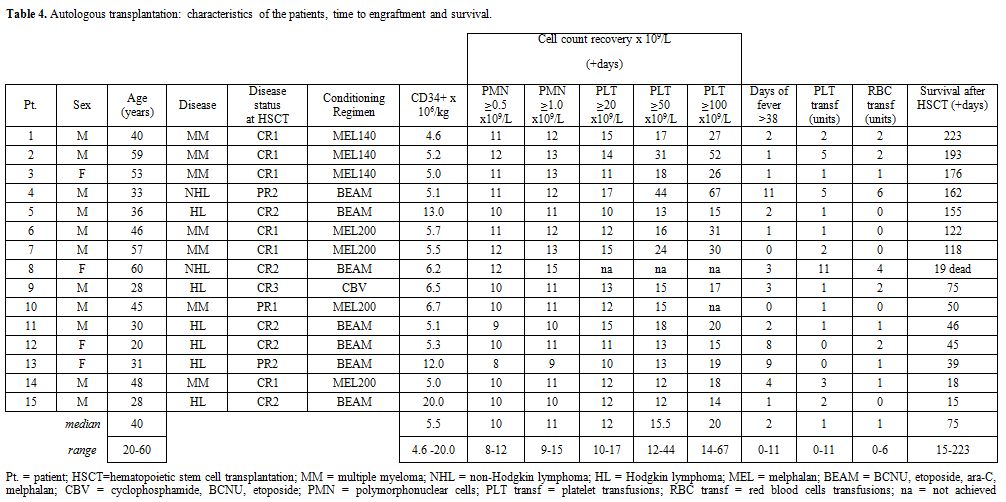

characteristics of the patients and the data of stem cell collection,

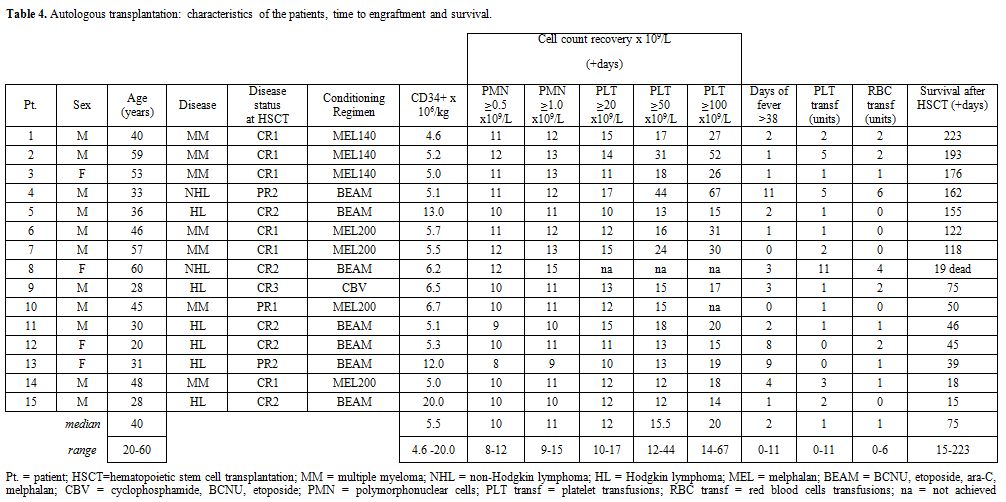

transplantation and engraftment are reported in table 4.

There were 15 patients, 11 males and 4 females. Median age was 40 years

(range 20 to 60). MM patients were 7, HL were 6 and NHL were 2. Status

of disease was CR1 in 4, CR2 in 5, PR1 in 3 and SR in 2. Following the

high-dose therapy, all the patients received G-CSF 5 mcg/kg to speed

engraftment. All received antiviral and antifungal

prophylaxis. The median number of CD34+ cells infused was 5.5 x 106/Kg

(range 4.6 to 20.0). All patients fully engrafted but one who died with

an acute heart failure on day+19 with granulocyte engraftment but

without platelet engraftment. In this series, granulocyte engraftment

(≥0.5 x 109/L) occurred on (median) day +11 with a narrow range from 9 to 12. Platelet engraftment (≥20.0 x 109/L)

occurred on (median) day +12, range 10 to 17. Thirteen out of the 15

patients underwent a febrile complication, with or without bacterial

isolation. Only one patient had a life-threatening complication, with

intestinal perforation, but underwent a successful surgical

intervention. Data on disease reevaluation are not presented as

follow-up is currently too short. All patients but one are alive at a

median of 75 days from transplant (range 15-223).

|

Table 4.

Autologous transplantation: characteristics of the patients, time to engraftment and survival. |

First allogeneic transplants:

The initial allogeneic program was set up with the aim to offer a cure

to the most frequent hematological disease in the region,[9] i.e. thalassemia.[10]

More than one thousand patients with thalassemia live in the area of

Sulaymaniyah, most of them are children belonging to large families and

having therefore a high probability of a matched family donor. Patients

eligible to transplant were considered those with low-risk

characteristics (age ≤ 7 years, liver size ≤ 2 cm below costal margin)

and a HLA matched sibling donor.[11,12] A downstaging

protocol with hydroxyurea and deferoxamine or deferasirox was adopted

in cooperation with the Thalassemia & Congenital Blood Diseases

Center in Sulaymaniyah directed by LR. Conditioning regimen included iv

busulfan and cyclophosphamide.[13] GvHD and rejection prophylaxis included ATG,[14]

from day -12 to -10, and cyclosporin, methotrexate and

methylprednisolone. The first allogeneic HSCT was performed on October

8th, 2016 and up to now overall 3 patients (2 females, 1 male)

underwent HSCT. All of them received GCSF-primed bone marrow[15] from

an HLA matched sibling. All donor/recipient couples shared the

same blood group and were CMV concordant, i.e. all CMV positive.

Engraftment occurred at a median time of 17 days. No major

complications were observed in the early aplastic phase after HSCT. One

patient developed grade II aGvHD and other potentially life-threatening

complications (CMV enterocolitis, low grade microangiopathy, PRES)

which resolved with proper treatment. All three patients have been

already discharged at home (on day +25, +27 and +96, respectively);

they are alive and well, continuing immunosuppression. Two of them are

already transfusion independent, the third, though full donor chimera,

having just recovered from many complications, not yet.

Discussion

Iraqi

Kurdistan first gained autonomous status in 1970 following an agreement

with the Iraqi government, and was re-confirmed as an autonomous entity

in 2005. The region has considerable oil and mineral resources.

However, due to the current conflict with the Islamic State, with more

than a million Syrian and Iraqi refugees seeking shelter in the Kurdish

territory, and also due to the fall of oil price, since 2012 the

country entered a deep economic crisis that also involved the health

system. The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, through the AICS, is

regularly supporting the Kurdish population also with health and social

projects.

We decided to dedicate our efforts to the

development of HSCT at the HCH of Sulaymaniyah mainly for two reasons.

First, HCH is today the main center in the Kurdish territory treating

hematologic malignancies and congenital disorders as thalassemia major,

the latter occurring at high frequency in Kurdistan. Second, at the

time of our first visit the HCH counted already with most of the

facilities necessary for an HSCT program, nevertheless an external

support would be needed.

Specifically, in the project we

developed at the HCH, the capacity-building methodology addressed the

implementation of a sustainable HSCT program through the collaboration

with experts in the field of adult hematology, pediatric

hemato-oncology, transfusion medicine, apheresis, infectious diseases,

nursing, cell manipulation, molecular biology and biophysics coming

from different Italian institutions. Almost all these experts had a

specific and long-lasting experience in the field of HSCT, and were

selected not only on the basis of their competence, but also of their

previous experience of cooperation with developing countries. All of

them were volunteers, while the non-governmental organization ICU

provided funds administration and reporting.

It is a common

belief that among the main obstacles in the implementation of

technically sophisticated procedures, as it is the case for HSCT, the

most important are the frequent lack of a priority scale, the absence

of teamwork as well as of appropriate methodology for problem-solving,

decision-sharing and quality management. A tendency not to establish a

transparent and effective responsibility tree is another factor.

All these issues are more prominent in developing countries, where also

procurement of resources and consequently of instrumentation and

reagents is often critical.

Since the beginning our efforts were

dedicated to training. Different techniques were used, not only the

traditional lectures and seminars, but principally the coaching method.

Written protocols and procedures were developed, and the method of

shared decisions was adopted to solve the clinical and laboratory

problems. This is a key function not only for the start-up but also for

quality control and improvement.

On-site training and coaching

represent an innovative method to establish a sustainable activity in

developing countries, as alternative to a more traditional one, where

local professionals to be trained are brought to the specialized

center(s) with higher expenditure and less predictable final results.

At present, we have no evidence that on-site training has more efficacy

compared with the traditional methodology, and what are the situations

where it would be more appropriate. With all the current limitations

for immigration policies, in the future more projects based on capacity

building on-site will probably be developed, and more data will be

available.

With the start-up of the autologous transplantation

program in June 2016 the HCH progressively developed an autonomous

capacity, and consolidated the technical skills not only in the fields

of apheresis, cell manipulation and immunohematology, but also in the

infection control.[16] In fact, by the end of 2016

among the 15 patients autografted, only one developed a

life-threatening infectious complication, but was eventually rescued.

Another patient died, due to sudden heart failure following initial

engraftment, a complication likely to be in part linked to age and a

borderline cardiac function. More severe criteria for admission were

consequently setup. Overall, the preliminary results seem encouraging

with prompt and stable hematologic recovery in all and few severe

complications.

The allogeneic transplantation program for

thalassemia at HCH, carries many advantages for the country: it reduces

psychosocial and financial burden for families and allows significant

saving for the government.[17] The estimated costs of

performing locally HSCT are lower than in the countries where patients

were previously referred; a systematic analysis of this costs will soon

be performed. Moreover, the new skills acquired together with the

continuation of cooperation are paramount for further implementing the

activity and extending the transplantation accessibility to children

with other disorders, as leukemias, bone marrow failures,

immune-deficiencies and others.

Here only the initial results of

the HSCT activity at the HCH are reported. We are aware that, after

start-up, transplantation activity needs resources and organization

over the medium and long term to ensure full autonomy of the Center. To

that purpose we also introduced the center to the international context

registering it as full member in the EBMT, and promoted the search for

scientific grants in order to allow medical doctors and other

professionals to visit other centers in Europe and the US. In addition,

a new project on pediatric hematology was submitted to the AICS and

recently funded. This new project, managed by the NGO AVSI, is aimed at

improving biological and clinical aspects of childhood leukemia

management at the HCH, but also to strengthen the transplantation

program, especially in the allogeneic field.

Conclusions

Thanks

to the cooperation initiative we described, the HCH is the only center

performing also allogeneic HSCT in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region, and in

the whole Iraq. We conclude that international cooperation may be of

great value also in the field of high-technology medicine, and may

contribute to improve the capabilities even of centers in critical

contexts, representing a valuable instrument also in fostering

country-to-country scientific exchanges.

Acknowledgements

We

are greatly indebted to Miss Sham O. Hamawandi, of the HCH secretary,

who made an incredible work coordinating the efforts of the Italian and

Kurdish teams. We also thank Dr. Francesca Bonifazi (President of

GITMO) for facilitating the recruitment of volunteer medical doctors.

Dr. Aleksandra Babic (President of the EBMT nursing board) and Dr.

Giampaolo Gargiulo (Responsible for the GITMO nurse group) contributed

substantially to the success of the project by selecting the best

professionals among the nurses in Italy and other countries in

Europe. Dr. Giorgio Dini was of great help in the construction of

the training program. A number of institutions provided supplementary

resources to the project. Dr. Roberto Nannerini (Arcobaleno

Association) and Prof. Alberto Ciferri (Jepa-Limmat Foundation) gave a

fundamental contribution with dedicated grants for the stages of two

biologists in Italian institutions. Under its Visitor Training Program

the American Society of Hematology also funded a stage in Italy of a

Kurdish medical doctor. We would never have succeeded without the

help of many Kurdish authorities, in particular Dr. Rekawt H. Rashid

Karim (Minister of Health) and Dr. Meran Mohamad Abas (Director of

Health, Sulaimanyah). The Iraq Program Coordinator of the Italian NGO

“Emergency”, Eng. Hawar Mustafa, provided us a with a fraternal support

and was often of incredible help with bureaucracy. We wish to thank him

warmly. We want to tribute a special acknowledgment to the Italian

Consul in Erbil, Dr Alessandra Di Pippo, and the Italian Ambassador in

Baghdad Dr Marco Carnelos who assumed the project as a priority for the

Italian diplomacy and personally did any effort to sustain its

development also contributing to pose the cornerstone of the first

Kurdish HSCT center at the Hiwa Cancer Hospital in Sulaymaniyah. A

special thank for Prof Eduardo Missoni (Global Health and Development,

Bocconi Management School) who reviewed the manuscript, we feel

indebted for his criticism and encouragement.

References

- Gratwohl A, Pasquini MC, Aljurf M, Atsuta Y,

Baldomero H, Foeken L, Gratwohl M, Bouzas LF7, Confer D, Frauendorfer

K, Gluckman E, Greinix H, Horowitz M, Iida M, Lipton J, Madrigal A,

Mohty M, Noel L, Novitzky N, Nunez J, Oudshoorn M, Passweg J, van Rood

J, Szer J, Blume K, Appelbaum FR, Kodera Y, Niederwieser D; Worldwide

Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WBMT). One million

haemopoietic stem-cell transplants: a retrospective observational

study. Lancet Haematol. 2015 Mar;2(3): e91-100. Epub 2015 Feb 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00028-9

- Garriga M (2013): The Capacity Building Concept. Available from http://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/The_Capacity_Building_Concept

- Brando

B, Siena S, Bregni M, Gianni AM, Grillo P, Sommaruga E. A standardized

flow cytometry protocol for mobilized peripheral CD34+ cells estimation

and collection for autotransplantation in cancer patients. Eur J

Histochem 1994; 38: 21-6. PMid:8547706

- Calvet

L, Cabrespine A, Boiret-Dupré N, Merlin E, Paillard C, Berger M, Bay

JO, Tournilhac O, Halle P. Hematologic, immunologic reconstitution, and

outcome of 342 autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantations

after cryopreservation in a -80°C mechanical freezer and preserved less

than 6 months. Transfusion. 2013 Mar;53(3):570-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03768.x

- Santoro

A, Mazza R, Pulsoni A, Re A, Bonfichi M, Zilioli VR, Salvi F, Merli F,

Anastasia A, Luminari S, Annechini G, Gotti M, Peli A, Liberati AM, Di

Renzo N, Castagna L, Giordano L, Carlo-Stella C. Bendamustine in

combination with gemcitabine and vinorelbine is an effective regimen as

induction chemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation for

relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of a multicenter

phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Sep 20;34(27):3293-9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4466

- Indovina

A, Liberti G, Majolino I, Buscemi F, Scimè R, Gentile S, Vasta S,

Pampinella M, Cappuzzo V, Santoro A. Cyclophosphamide 4 g/m2 plus

rhG-CSF for mobilization of circulating progenitor cells in malignant

lymphomas. Int J Artif Organs. 1993 Dec;16 Suppl 5:30-4.

PMid:7516915

- Bashey

A, Donohue M, Liu L, Medina B, Corringham S, Ihasz A, Carrier E, Castro

JE, Holman PR, Xu R, Law P, Ball ED, Lane TA. Peripheral blood

progenitor cell mobilization with intermediate-dose cyclophosphamide,

sequential granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor and

granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor, and scheduled commencement of

leukapheresis in 225 patients undergoing autologous transplantation.

Transfusion. 2007 Nov;47(11):2153-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01440.x PMid:17958545

- Pierelli

L, Maresca M, Piccirillo N, Pupella S, Gozzer M, Foddai ML, Vacca M,

Adorno G, Coppetelli U, Paladini U. Accurate prediction of autologous

stem cell apheresis yields using a double variable-dependent method

assures systematic efficiency control of continuous flow collection

procedures. Vox Sang. 2006 Aug;91(2):126-34. PubMed PMID: 16907873. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00796.x PMid:16907873

- Hamamy

HA, Al-Allawi NA. Epidemiological profile of common haemoglobinopathies

in Arab countries. J Community Genet. 2013, 4:147-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-012-0127-8 PMid:23224852 PMCid:PMC3666833

- Lucarelli

G, Galimberti M, Polchi P, Angelucci E, Baronciani D, Giardini C,

Andreani M, Agostinelli F, Albertini F, Clift RA. Marrow

transplantation in patients with thalassemia responsive to iron

chelation therapy. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329: 840-4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199309163291204 PMid:8355742

- Angelucci

E, Matthes-Martin S, Baronciani D, Bernaudin F, Bonanomi S, Cappellini

MD, Dalle JH, Di Bartolomeo P, de Heredia CD, Dickerhoff R, Giardini C,

Gluckman E, Hussein AA, Kamani N, Minkov M, Locatelli F, Rocha V,

Sedlacek P, Smiers F, Thuret I, Yaniv I, Cavazzana M, Peters C; EBMT

Inborn Error and EBMT Paediatric Working Parties. Hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation in thalassemia major and sickle cell disease:

indications and management recommendations from an international expert

panel. Haematologica. 2014, 99:811-20. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2013.099747 PMid:24790059 PMCid:PMC4008115

- Sabloff

M, Chandy M, Wang Z, Logan BR, Ghavamzadeh A, Li CK, Irfan SM, Bredeson

CN, Cowan MJ, Gale RP, Hale GA, Horan J, Hongeng S, Eapen M, Walters

MC. HLA-matched sibling bone marrow transplantation for ß-thalassemia

major. Blood. 2011, 117:1745-50. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-09-306829 PMid:21119108 PMCid:PMC3056598

- Mathews V, Savani BN. Conditioning regimens in allo-SCT for thalassemia major. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2014; 49:607-10. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2013.216 PMid:24442250

- Goussetis

E, Peristeri I, Kitra V, Vessalas G, Paisiou A, Theodosaki M, Petrakou

E, Dimopoulou MN, Graphakos S. HLA-matched sibling stem cell

transplantation in children with ß-thalassemia with anti-thymocyte

globulin as part of the preparative regimen: the Greek experience. Bone

Marrow Transplant, 2012;47:1061-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2011.219 PMid:22080966

- Deotare

U, Al-Dawsari G, Couban S, Lipton JH. G-CSF-primed bone marrow as a

source of stem cells for allografting: revisiting the concept. Bone

Marrow Transplant, 2015; 50:1150-6 https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.80 PMid:25915812

- Girmenia

C, Viscoli C, Piciocchi A, Cudillo L, Botti S, Errico A, Sarmati L,

Ciceri F, Locatelli F, Giannella M, Bassetti M, Tascini C, Lombardini

L, Majolino I, Farina C, Luzzaro F, Rossolini GM, Rambaldi A.

Management of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in

stem cell transplant recipients: an Italian multidisciplinary consensus

statement. Haematologica. 2015 Sep;100(9):e373-6. doi:

10.3324/haematol.2015.125484 https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2015.125484

- Faulkner

LB, Uderzo C, Masera G. International cooperation for the cure and

prevention of severe hemoglobinopathies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;

35: 419-23. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31829cd920. Review. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e31829cd920

[TOP]