Jameel Al-Ghazaly¹,², Waled Al-Dubai³, Munasser Abdullah4 and Leila Al-Gharasi²

1 Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana'a University, Sana'a, Yemen

2 Department of Medicine, Hematology Unit, Al-Jomhori Teaching Hospital, Sana'a, Yemen

3 Department of Biochemistry and cytogenetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana'a University, Sana'a, Yemen

4 Al-Amana Specialized Laboratories, Sana'a, Yemen

Corresponding

author: Jameel Al-Ghazaly, Consultant Hematologist and Associate

Professor, Sana'a University, Head of Hematology Unit, Al-Jomhori

Teaching Hospital, Sana'a, Yemen. Tel: 00967-738168457. E-mail:

jameel_alghazaly@yahoo.com

Published: September 1, 2017

Received: June 26, 2017

Accepted: August 3, 2017

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017056 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.056

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and objectives:

Delay in the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) particularly in

non-endemic areas is associated with higher mortality. In our

experience, we found that marked bone marrow eosinopenia was a very

frequent accompaniment of VL and might be a useful clue for the

diagnosis, which indicates the opportunity for further morphological

assessment. The aim of this study was to describe the hematological

characteristics including peripheral blood and bone marrow findings of

Yemeni adults and children with VL.

Methods:

We conducted a descriptive analytic study to evaluate systematically

peripheral blood and bone marrow findings of Yemeni adults and children

with VL. Peripheral blood and bone marrow aspiration of patients with

bone marrow aspirate confirmed VL were examined. Forty-seven patients

with the main age (±SD) of 17.34±11.37 years (Range: 1-60) were

included in the study. Fifty-one non-VL subjects with splenomegaly and

pancytopenia or bicytopenia served as control group.

Results:

All patients with VL had anemia, 41 (87%) leukopenia, 42 (89%)

neutropenia, 44 (94%) thrombocytopenia, 42 (89%) eosinopenia, 34 (72%)

pancytopenia and 13 (28%) had bicytopenia. In bone marrow examination

40 (85%) showed hypercellularity, 44 (94%) eosinopenia, 24 (51%)

dyserythropoiesis, 22 (47%) lymphocytosis, 8 (17%) plasmacytosis, 27

(57%) decreased iron stores and 20 (43%) showed decreased sideroblasts.

Comparison of VL patients with the control group showed significantly

more frequent peripheral blood eosinopenia and lymphopenia and marrow

eosinopenia. There was no significant difference between adults and

children in any of the hematological features.

Conclusion:

Anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, eosinopenia,

pancytopenia and marked bone marrow eosinopenia were the most common

findings. The finding of marked bone marrow eosinopenia is a

significant clue for the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in

patients who present with splenomegaly associated with cytopenias. This

finding is particularly valuable in non-endemic areas.

|

Introduction

The

hematological features of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) have evoked

particular interest because of their high frequency and severity and

because they cause significant mortality and morbidity.[1,2,3]

There are frequent reports of the hematological manifestations which

describe mainly their relative frequencies in different regions of the

world.[3,4] Common non-specific hematological features of VL include anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and pancytopenia.[3,5,6]

Such hematological features are also frequently encountered in patients

with hematological malignancies such as acute leukemia, lymphomas, and

myelodysplastic syndrome as well as various infectious diseases.[7]

There are also frequent reports of VL presenting as an autoimmune

disease mimicking autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis,

rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.[8,9] Higher rates of morbidity and mortality are consequences of the delay in diagnosis.[10,11,12]

VL is also reported to be one of the most common causes of fever of

unknown origin causing troublesome diagnosis in a European low-income

country.[13] In addition to the non-specificity of

clinical and general laboratory features of VL, the confirmatory

laboratory tests with the exception of identification of the parasites

in Giemsa stained tissue aspirates, are usually interpreted in the

light of clinical and epidemiological data which are not helpful in

non-endemic areas.[14,15] On the other hand, the

sensitivity of bone marrow aspirates, which is comparatively a safer

procedure compared to splenic aspirates for identification of the

parasite, was found to be proportional to the amount of time spent

searching for the amastigotes (65.5 percent and 95.4 percent at 5

minutes and one hour respectively).[16] Finding a

collection of hematological features will help to demand a diligent

search to confirm the diagnosis particularly in non-endemic areas. Only

a few reports have looked at hematological manifestations as helpful

clues for the diagnosis, which included mainly bone marrow cytological

features.[17,18] In Yemen, Leishmania IgG ELISA is

rarely available in some centres and experience showed it to be

unreliable because of the high frequency of false positive and false

negative results when compared to identification of the parasites in

Giemsa stained tissue aspirates. Such findings were also addressed by

WHO expert group who reported that a significant proportion of people

living in endemic areas with no history of VL is positive for

antileishmanial antibodies owing to asymptomatic infections.[15]

The experts also recommend that in areas of low endemicity more

accurate diagnostic algorithms are required that would include

parasitology in blood and bone marrow. The role of serology in the

diagnosis of VL has been reviewed.[19,20] PCR for the

diagnosis of leishmania is not available in Yemen, and only one report

has been recently published in which PCR was used for research purposes

with the collaboration of University of Malaya and reported the first

Molecular characterization of VL in Yemen.[21]

Therefore, identification of the parasites in Giemsa stained bone

marrow aspirate smears remains the only reliable diagnostic method for

the diagnosis of VL in Yemen.[3,22]

In our experience, we observed that in addition to known hematological

features, the presence of marked bone marrow eosinopenia constitutes a

crucial clue to the presence of visceral leishmaniasis in challenging

cases. Such evidence prompted a careful review of the smears searching

for amastigotes, which were identified -although sometimes with a

little and scanty distribution- in all suspected cases showing these

two features. The aim of this study is to evaluate systematically the

hematological characteristics of Yemeni adults and children with VL

including objective documentation of the frequency and degree

peripheral and bone marrow eosinopenia to find clues that may help to

arrive at the diagnosis early. This procedure by avoiding delay in

specific treatment will decrease morbidity and mortality. A full

epidemiological study of VL in Yemen is not available. The causative

organisms are Leishmania donovani complex (anthroponotic VL) and

Leishmania infantum complex (zoonotic VL). The pattern of VL in Yemen

derives from the few studies published. The disease seems to be endemic

in the country, particularly in Hajjah, Taiz and Amran governorates of

the Northern part of the country and Lahj and Abyan governorates of the

south of the country.[3,22]

Materials and Methods

The

study is a descriptive analytic study conducted in Sana'a, which is the

capital city of Yemen, at the hematology unit of Al-Jomhori teaching

hospital which is a referral tertiary teaching hospital. The hematology

unit deals with all types of hematological diseases including

hematological malignancies which are referred from all over the

country. The study included 47 patients with VL who were

prospectively evaluated and managed at our center between October 2010

and October 2014. Their diagnosis was confirmed by identification of

amastigotes in Giemsa stained bone marrow smears. Complete blood count

(CBC) was done for each patient using an automated cell counter (Sysmex

Automated machine, Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan), The white blood

cell count (WBC) differential and red blood cell (RBC) morphology were

confirmed manually by a well-trained laboratory hematologist and

adjusted accordingly. One peripheral blood Giemsa stained smear and

three bone marrow aspiration Giemsa stained smears were examined by the

consultant laboratory and clinical hematologist. Informed consent was

obtained from the patients or responsible persons and the study was

approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health

Sciences of Sana’a University.

The control group included 51

subjects, randomly selected from the records of 207 non-VL patients, 60

years old or younger (considering that the maximum age for patients

with VL was 60 years old), who presented with fever, splenomegaly and

pancytopenia or bicytopenia during the period of the study between

October 2010 and October 2014. Their presenting CBC and WBC

differential were taken before any treatment. They were performed by

the same machine and in the same way as for all patients including

patients with VL. The bone marrow examination was carried out at

initial presentation as part of the evaluation of their splenomegaly

and cytopenia. Their marrow aspiration Giemsa stained smears were

reviewed to determine the eosinophil series percentage and to compare

the results with those of patients with VL. They were examined by the

same laboratory and clinical hematologist who reviewed the bone marrow

smears of patients with VL.

Definitions.

Bone marrow eosinopenia: eosinophil series count of less than 0.3% of

total marrow myeloid cells calculated as the average number in at least

20 cellular fields examined i.e. at least 20x200= 4000 cells were

counted [Normal range of eosinophils on aspirated bone marrow: 0.3-4.0%

and the normal mean: 2.2%].[23]

Dyserythropoiesis:

Presence of dysplastic changes of erythropoiesis including

megaloblastic features, binuclear and polynuclear normoblasts and other

dyserythropoietic features (e.g. internuclear bridges, nuclear budding)

with a frequency of > 5 per 100 erythroid cells

Hypercellular marrow: a cellularity > 50% in adults and > 80% in children.

Increased lymphocytes (marrow): Lymphocytes > 5% of total non-erythroid cells in adults and > 10% in children.

Increased plasma cells (marrow): Plasma cells > 5% of total non-erythroid cells in both adults and children.

Hemophagocytosis:

Presence in the bone marrow of macrophages which phagocytize blood and

bone marrow cells including red cells, erythroblasts, other leukocytes

and or platelets.

Evaluation of iron stores: decreased marrow iron

stores: less than one iron-positive cell, on the average for each x 40

field or absent iron-positive cells; increased marrow iron stores: more

than two iron-positive cells for each x 40 field. Decreased marrow

sideroblasts: sideroblasts less than 3% of total erythroblasts in the

marrow.[24]

Statistical analysis.

The data were collected, tabulated and compiled in a computer database.

SPSS version 21 was used to analyze data. Frequencies and percentages

were used to describe categorical data. Unpaired Independent Samples T

test was used to evaluate the comparison between adults and children

regarding the means of Hb, PCV, MCV, MCH, WBC, platelet, neutrophil,

lymphocyte, monocyte and eosinophil counts. Chi squared test was used

to compare the degree of abnormal peripheral blood counts and also the

peripheral blood and bone marrow morphological data between adults and

children. Unpaired Independent Samples T test was used to evaluate the

comparison between Patients with VL and control subjects regarding the

means of Hb, WBC, platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and

eosinophil counts. Chi squared test was used to compare the degree of

abnormal peripheral blood counts and bone marrow eosinopenia between VL

patients and controls.

Results

Forty-seven

(32 males and 15 females) patients with the main age (±SD) of

17.34±11.37 years (Range: 1-60) were included in the study. Of these

patients, 28 (59.6%) were adults aged 16-60 years with a mean age (±SD)

of 24.3 years ±9.2 and 19 (40.4%) patients were children aged 1-15

years with a mean age (±SD) of 7.1 years ±4.7.

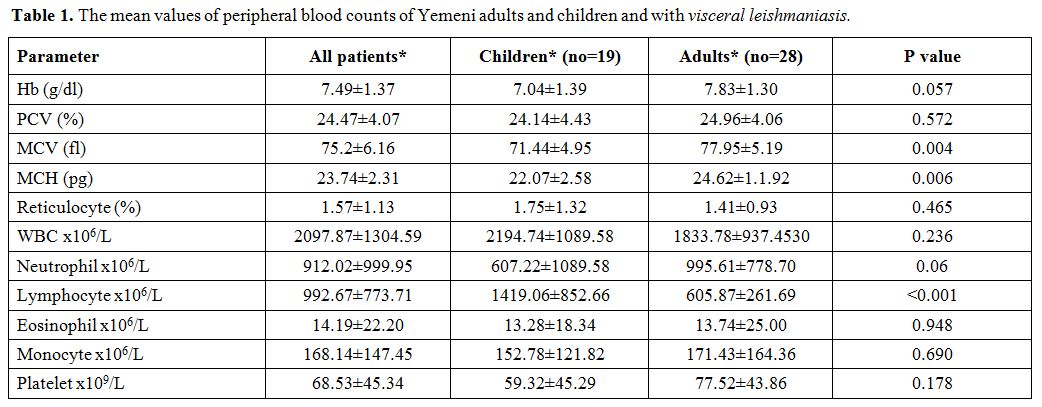

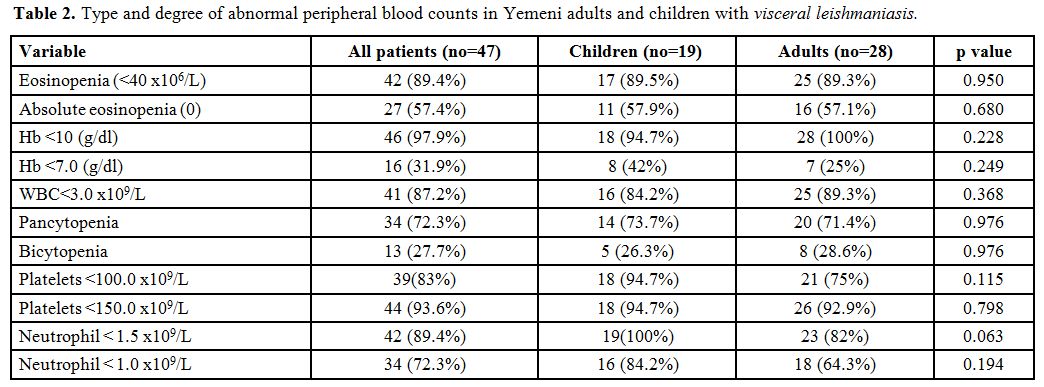

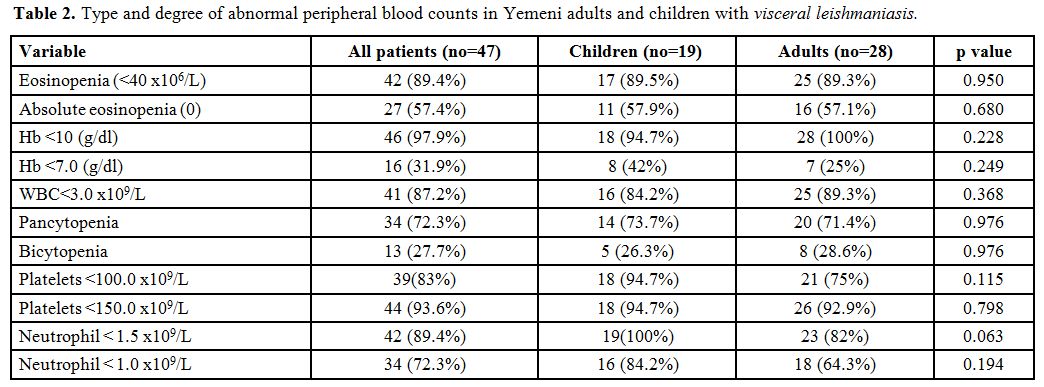

Table 1 shows the mean values of the peripheral blood counts of adults and children with VL and table 2 shows the type and degree of abnormal peripheral blood counts.

|

Table 1.

The mean values of peripheral blood counts of Yemeni adults and children and with visceral leishmaniasis. |

|

Table 2. Type and degree of abnormal peripheral blood counts in Yemeni adults and children with visceral leishmaniasis. |

All

patients had moderate to severe anemia (Hb range: 4.6-10.4 g/dl)

including 16 (32%) patients who had severe anemia; only one patient had

Hb > 10 g/dl (10.4 g/dl).

Forty-one (87%) patients had

leukopenia, and 42 (89.4%) patients had neutropenia including 34

(72.3%) patients who had significant neutropenia.

Thrombocytopenia

was present in 44 (93.6%) patients including 39 (83%) patients who had

significant thrombocytopenia. Eosinopenia was present in 42 (89.4%)

patients including 27 (57.4%) patients who had absolute eosinopenia.

All patients had either pancytopenia or bicytopenia: 34 (72.3%) and 13 (27.7%) respectively.

The

red blood cell morphological characteristics of Yemeni adults and

children with visceral leishmaniasis showed that anisocytosis,

anisochromia, and microcytic RBCs were the most common red blood cell

morphological findings which were present in 30 (63.8%), 25 (53.2%) and

23 (49%) respectively. Ten (21%) patients had poikilocytosis, and five

(10%) had tear drop red blood cells.

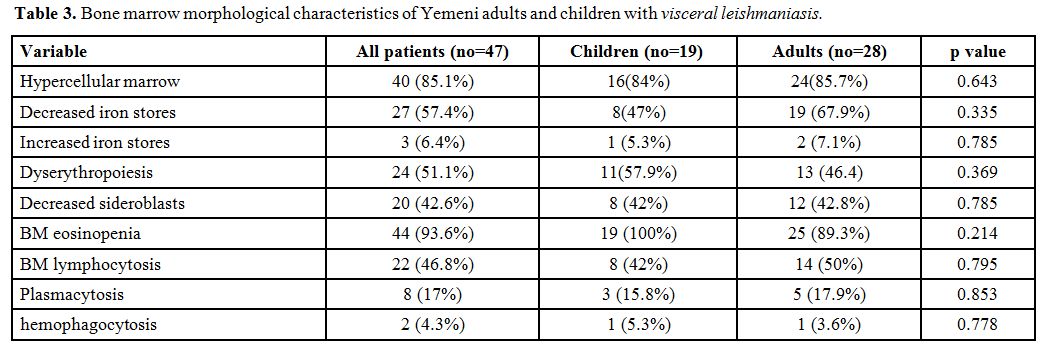

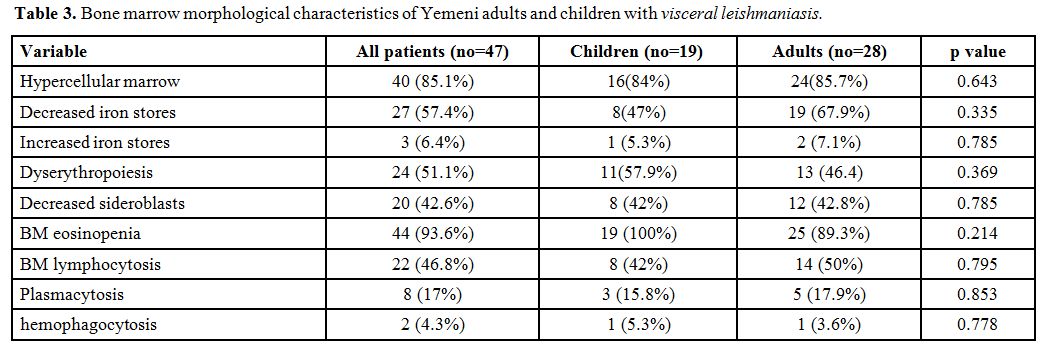

Table 3

shows the bone marrow morphological characteristics of Yemeni adults

and children with visceral leishmaniasis. Regarding bone marrow

morphological findings, marked bone marrow eosinopenia was the most

common finding which was seen in 44 (93.6%) patients. Forty (85%)

patients had hypercellular marrow, and 24 (51%) patients had

dyserythropoiesis. Decreased iron stores were present in 27 (57.4%)

patients, and 20 (42.6%) had a reduced number of sideroblasts. Only

three (6.4 %) patients had increased iron stores. Hemophagocytosis was

recognized in two (4.3) patients, and bone marrow plasmacytosis was

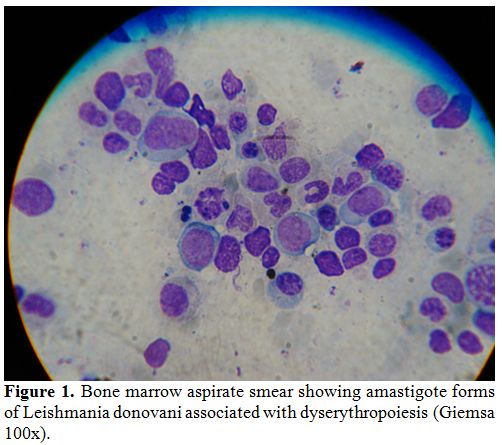

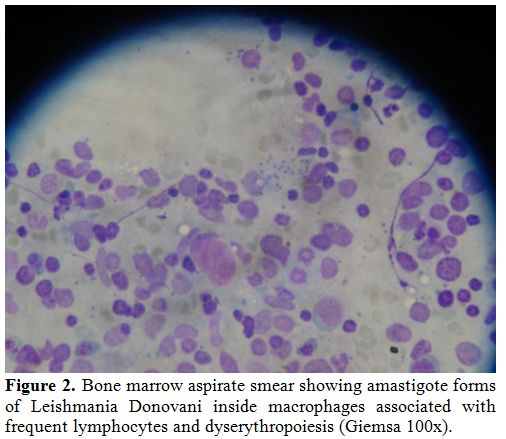

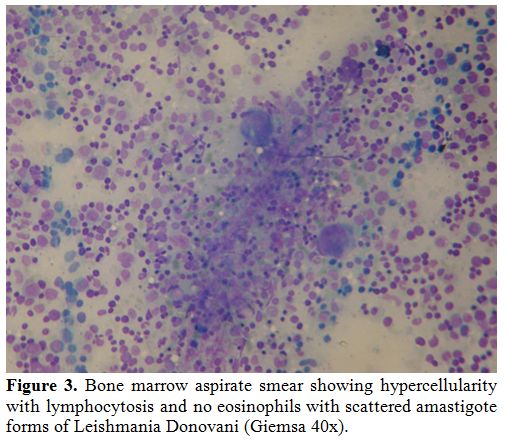

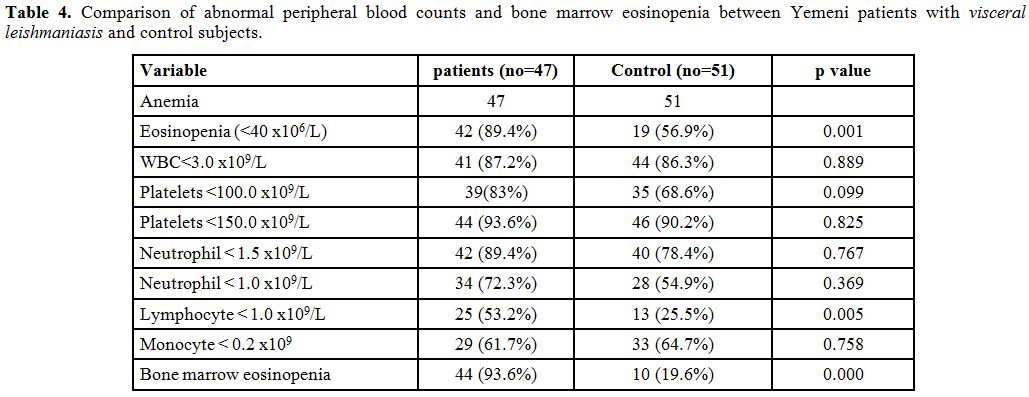

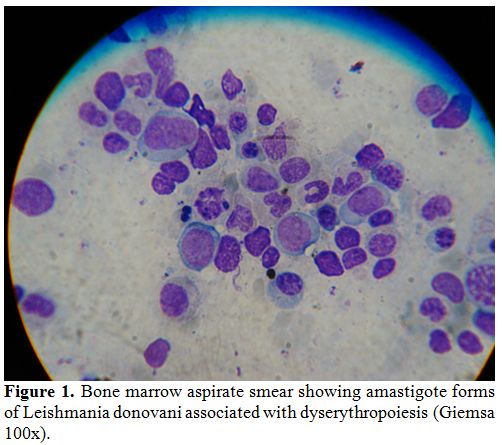

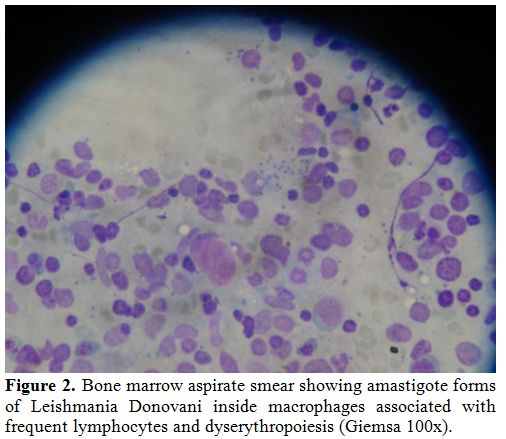

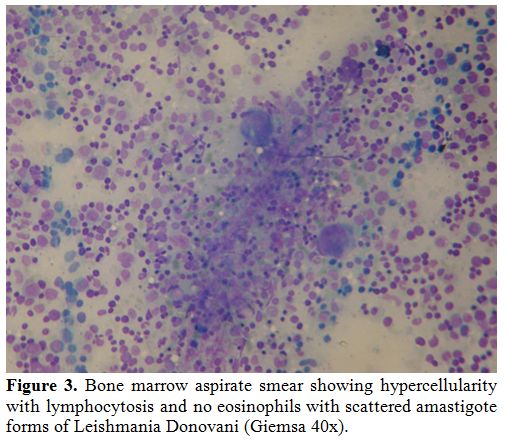

seen in eight (17%) patients (Figures 1,2,3).

|

Table 3.

Bone marrow morphological characteristics of Yemeni adults and children with visceral leishmaniasis. |

|

Figure 1. Bone marrow aspirate smear

showing amastigote forms of Leishmania donovani associated with

dyserythropoiesis (Giemsa 100x). |

|

Figure 2. Bone marrow aspirate smear

showing amastigote forms of Leishmania Donovani inside macrophages

associated with frequent lymphocytes and dyserythropoiesis (Giemsa

100x). |

|

Figure 3. Bone marrow aspirate smear

showing amastigote forms of Leishmania Donovani inside macrophages

associated with frequent lymphocytes and dyserythropoiesis (Giemsa

100x). |

The

control group included 51 subjects (30 males and 21 females) with the

main age (±SD) of 20.71±11.92 years (Range: 0.5-60). The mean values of

the peripheral blood counts of control subjects was 7.80±1.75 (g/dl)

for Hb, 2703.92±826.55 (x106/L) for WBC, 1069.76±626.50 (x106/L) for neutrophils, 1347.76±630.26 (x106/L) for lymphocytes, 88.10±108.84 (x106/L) for eosinophils, 201.06±197.72 (x106/L) for monocytes and 74.65±62.68 (x109/L)

for platelets. Comparison of the mean values of peripheral blood counts

between patients with VL and control subjects showed no significant

difference in any of the above mean values except that patients had

significantly lower eosinophil counts (p value 0.000) and lower

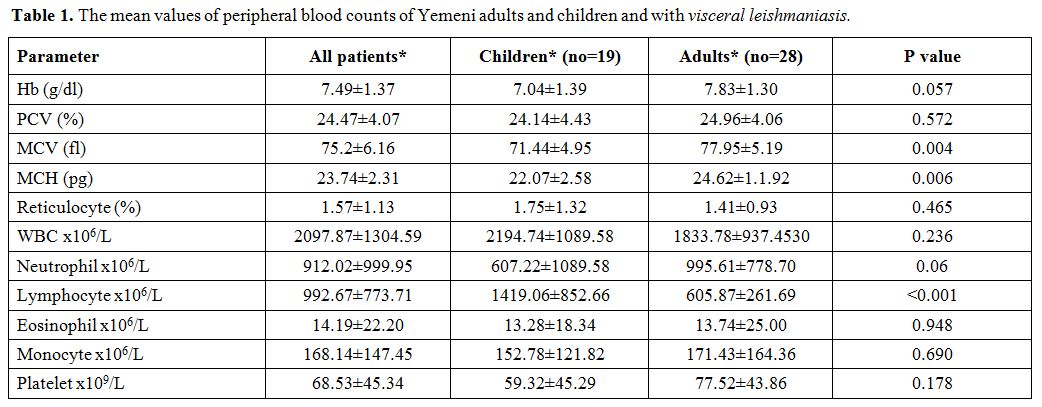

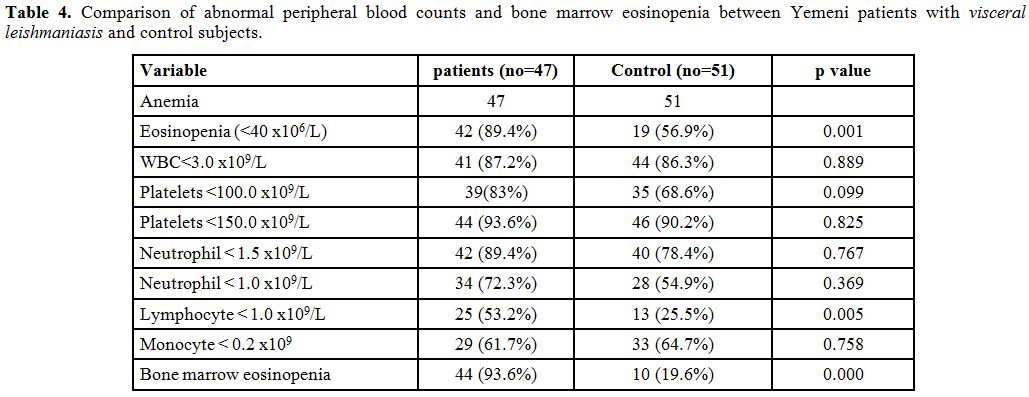

lymphocyte count (p value 0.014). Table 4

shows comparison of abnormal peripheral blood counts and bone marrow

eosinopenia between Yemeni patients with VL and control subjects.

Patients had significantly more peripheral blood eosinopenia and

lymphopenia and bone marrow eosinopenia compared to control

subjects.

|

Table 4. Comparison of abnormal peripheral blood counts and bone marrow eosinopenia between Yemeni patients with visceral leishmaniasis and control subjects. |

Discussion

Our

study showed that anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia,

eosinopenia, and pancytopenia were the most common peripheral blood

findings in patients with VL and that hypercellularity, eosinopenia,

dyserythropoiesis, lymphocytosis and decreased marrow iron were the

most common bone marrow findings.

Most hematological features

including anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and pancytopenia are

non-specific. Such features are frequent in patients with other

infectious diseases, some hematological disorders and some autoimmune

collagenous diseases.[7,25-28]

Diagnosis of VL is straight forward in endemic areas where the disease

is suspected and aided by confirmatory laboratory tests including

reliable serological tests.[14] However, in

non-endemic areas, the differential diagnosis includes a broad spectrum

of diseases as mentioned above and serological diagnosis is not

reliable.[15] Finding amastigotes in tissue smears is

the most reliable diagnostic test. Splenic aspiration is a risky

procedure and is not a usual in non-endemic areas. Bone marrow

aspiration remains the safest procedure. However, the sensitivity of

such method depends on the time spent examining the smears.[16]

Paying careful oriented attention and adequate time searching for the

parasites increases the sensitivity to around 100%. However, such a

time which may take few hours cannot be paid for all patients

presenting with the above hematological features because of the high

incidence of the diseases presenting with such features. Finding

additional clues may limit the number of cases highly suspected of

being VL, which need careful, time-consuming study.

The peripheral

blood features of our patients which included anemia, thrombocytopenia,

leukopenia, bicytopenia, and pancytopenia are not different from those

reported from other studies in Asia, Africa, and Mediterranean region

or South America.[4,29]

Hypercellular marrow and dyserythropoiesis were also common in our

patient group which is similar to that reported in other studies.[30,31] Bone marrow lymphocytosis was also frequent among our patients similar to other studies.[6]

Our patients also had significant peripheral blood lymphocytopenia. The

presence of peripheral blood lymphopenia in association with bone

marrow lymphocytosis has been explained by the notion that lymphocytes

migrate to the affected lymphoid tissues to build an inflammatory

response and that bone marrow lymphocytosis is a compensatory response

that provides lymphocytes to organs affected by the parasite.[32,33]

Only one child and one adult of our patients had bone marrow features

of hemophagocytosis. Hemophagocytosis was reported to be a rare

occurrence in patients with visceral leishmaniasis causing diagnostic

dilemma and unusual presentation.[11,34]

Our patients showed decreased marrow iron which is consistent with

their common finding of microcytic red blood cells. This picture is due

to the malnutrition these patients usually have as a consequence of

anorexia and is also explained by the fact that the disease affects the

poor population predominantly.[25,35] Severe anemia, malnutrition and long duration of illness were shown to be associated with an increased risk of death.[25,36]

These issues should be addressed in evaluating and managing patients

with VL. The marked bone marrow eosinopenia associated with marked

peripheral blood eosinopenia are the characteristics which were most

common in our patients with VL and usually are not reported both

together in other simulating illnesses. Bone marrow eosinopenia in VL

has not been signaled in humans so far. However, it has been reported

in symptomatic canine VL as opposed to asymptomatic canine VL and was

found to be correlated with peripheral eosinopenia and it has been

regarded together with peripheral blood lymphocytopenia as a biomarker

of severe disease.[37] Eosinophilic hypoplasia in

symptomatic canine VL has been explained by bone marrow dysfunction,

which may have contributed to the severe eosinopenia.[37,38]

On the other hand, Eosinophil infiltration in the lymph-nodes of mice

infected by Leishmania major was found to be influenced by sex and

parasitic load and that it reflects ineffective inflammation.[39]

The previous studies in humans on hematological manifestations of VL

did not evaluate bone marrow eosinopenia as a feature or as a clue to

the diagnosis of the disease. A single study reported three of 18 bone

marrow aspirates who had prominent marrow eosinophils.[40]

However, the authors themselves of the study did not find any report of

similar observation in the searched medical literature. We also didn't

find other reports of this finding of marrow eosinophilia. Therefore,

secondary causes of eosinophilia could not be excluded in these cases.

Furthermore, the percentage of those patients with eosinophilia was too

small to regard it a significant finding: 3/18 [16%].[40]

Our study also showed that there was no significant difference between

adults and children regarding peripheral blood and bone marrow

eosinopenia or concerning other hematological features.

Conclusions

Based

on the above findings we conclude that in the proper clinical setting

associated with peripheral blood cytopenias, the finding of marked bone

marrow eosinopenia is a critical clue for the diagnosis of symptomatic

VL demanding careful, lengthy search for the parasites in bone marrow

aspirate smears. This finding is particularly valuable in non-endemic

areas.

References

- Pace D (2014) Leishmaniasis. J Infect 69 S10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.016 PMid:25238669

- Ready PD. Epidemiolgy of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6:147-154 https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S44267 PMid:24833919 PMCid:PMC4014360

- Abdul

Hamid G, Gobah GA. Clinical and hematological manifestations of

visceral leishmaniasis in Yemeni children. Turk J Hematol 2009; 26:

25–28.

- Sarkari

B, Naraki T, Ghatee MA , Abdolahi KS, Davami MH. Visceral Leishmaniasis

in Southwestern Iran: A Retrospective Clinico-Hematological Analysis of

380 Consecutive Hospitalized Cases (1999-2014). PLOS ONE 2016;11(3):

e0150406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150406

- Agrawal

Y, Sinha AK, Upadhyaya P, Kafle SU, Rijal S, Khanal B. Hematological

profile in visceral leishmaniasis. Int J Infect Microbiol

2013;2(2):39-44 https://doi.org/10.3126/ijim.v2i2.8320

- Varma N, Naseem S. Hematologic Changes in Visceral Leishmaniasis/Kala Azar. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2010; 26: 78-78 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-010-0027-1 PMid:21886387 PMCid:PMC3002089

- Jain

A, Naniwadekar M. An etiological reappraisal of pancytopenia - largest

series reported to date from a single tertiary care teaching hospital.

BMC Hematol 2013;13:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-1839-13-10

- Tunccan

OG, Tufan A, Telli G, Akyürek N, Pamukçuoglu M, Yilmaz Get al. Visceral

Leishmaniasis Mimicking Autoimmune Hepatitis, Primary Biliary

Cirrhosis, and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Overlap. Korean J Parasitol

2012; 50 (2): 133-136 https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2012.50.2.133 PMid:22711924 PMCid:PMC3375451

- Cakar

M, Cinar M, Yilmaz S, Sayin S, Ozgur G, Pay S. A case of leishmaniasis

with a lupus-like presentation. Seminar Arthritis Rheum.

2015;45(1):e3-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.04.001 PMid:25953712

- Prasad

R, Muthusami S, Pandey N, Tilak V, Shukla J, Mishra OP. Unusual

presentations of Visceral leishmaniasis. Indian J Pediatr 2009;76:

843–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-009-0148-4 PMid:19475352

- Celik

U, Alabaz D, Alhan E, Bayram I, Celik T. Diagnostic dilemma in an

adolescent boy: hemophagocytic syndrome in association with kala azar.

Am J Med Sci 2007;334:139–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31812e97f4 PMid:17700207

- Driemeier

M, de Oliveira PA, Druzian AF, Lopes Brum GF, Pontes ER, Dorval ME,

Paniago AM. Late diagnosis: a factor associated with death from

visceral leishmaniasis in elderly patients. Pathog Glob Health

2015;109(6): 283-9. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000029 PMid:26257311 PMCid:PMC4727583

- Bosilkovski

M, Dimozva M, Stevanovic M, Cvetkovska VS, Duganovska M. Fever of

unknown origin--diagnostic methods in a European developing country.

Voinosanit Pregl. 2016;73(6):553-8. https://doi.org/10.2298/VSP140827050B

- Sakkas

H, Gartzonika C, Levidiotou S. Laboratory diagnosis of human visceral

leishmaniasis. J Vector Borne Dis

2016;53(1):8-16. PMid:27004573

- Report

of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the control of

Leishmaniasis, Geneve, 22-26 March 2010. Available at:

whqlibdoc.who.int, accessed: April, 2, 2017

- da

Silva MR, Stewart JM, Costa CH. Sensitivity of bone marrow aspirates in

the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. AM J Trop Med Hyg

2005;72(6):811-4 PMid:15964968

- Bhatia

P, Haldar D, Varma N, Marwaha RK, Varma S. A Case Series Highlighting

the Relative Frequencies of common/uncommon and Atypical/Unusual

Hematological Findings on bone marrow examination in cases of Visceral

Leishmaniasis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2011; 3: e2011035. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2011.035 PMid:22084650 PMCid:PMC3212968

- Chaufal

SS, Pant P, Chachra U, Singh P, Thapliyal N, Rawat V. Role of

Haematological Changes in Predicting Occurrence of Leishmaniasis- A

Study in Kumaon Region of Uttarakhand. J Clin Diag Res

2016;10(5):FC39-34. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/15438.7885

- Pagliano

P., Ascione T., Di Flumeri G., Boccia G., De Caro F. Visceral

leishmaniasis in immunocompromised: diagnostic and therapeutic approach

and evaluation of the recently released IDSA guidelines. Infez. Med

2016; 24(4): 265-271 PMid:28011960

- Franceschini

E, Puzzolante C, Menozzi M, Rossi L, Bedini A, Orlando G, Gennari W,

Meacc Mi, Rugna G, Carra E, Codeluppi M, Mussini C. Clinical and

Microbiological Characteristics of Visceral Leishmaniasis Outbreak in a

Northern Italian Nonendemic Area: A Retrospective Observational Study.

BioMed Research International Volume 2016 (2016), Article ID 6481028, 7

pages

- Mahdy

MAK, Al-Mekhlafi AM, Abdul-Ghani R, Saif-Ali R, Al-Mekhlafi HM,

Al-Eryani SM, Lim YAL, Mahmud R. First Molecular Characterization of

Leishmania Species causing Visceral Leishmaniasis among Children in

Yemen. PLOS ONE 2016;11(3): e0151265

.

.

- Al-Ghazaly

J., Al-Dubai W. The clinical and biochemical characteristics of Yemeni

adults and children with visceral leishmaniasis and the differences

between them: a prospective cross-sectional study before and after

treatment. Trop Doct 2016;46(4): 224-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049475515622862 PMid:26746626

- Bates

I, Burthern J. Bone marrow biopsy In: Dacie and Lewis Practical

Haematology, Bain B, Bates I, Laffan M, Lewis SM (eds), Churchill

Livingstone Elsevier, 11th edition 2012. p.130 .

- Ryan

DH. Examination of the marrow In: Williams Hematology, Kaushansky K,

Lichtman M, Beutler E, Kipps TJ, Seligsohn U, Prchal JT (eds), McGraw

Hill Medical, 8th edition 2011. p. 33.

- Collin

S, Davidson R, Ritmeijer K, Keus K, Melaku Y, Kipngetich S, Davies C.

Conflict and kala-azar: determinants of adverse outcomes of kala-azar

among patients in southern Sudan. Clin. Infect. Dis 2004; 38 (5):

612–19. https://doi.org/10.1086/381203 PMid:14986243

- Kopterides P, Halikias S, Tsavaris N. Visceral leishmaniasis masquerading as myelodysplasia. Am J Hematol 2003;74:198–199 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.10408 PMid:14587050

- Arlet

JB, Capron L, Pouchot J. Visceral leishmaniasis mimicking systemic

lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol 2010; 16: 203-204. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181dfd26f PMid:20511988

- Pagliano,

P., Costantini, S., Gradoni, L., Faella, F.S., Spasiano, A.,

Mascarella, G., Prossomariti, L., Fusco, U., Ricchi, P. Case report:

Distinguishing visceral leishmaniasis from intolerance to pegylated

interferon-a in a thalassemic splenectomized patient treated for

chronic hepatitis C. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

2008; 79(1): 9-11 PMid:18606757

- Chakrabarti

S, Sarkar S, Goswami BK, Sarkar N, Das S. Clinico-hematological profile

of visceral leishmaniasis among immunocompetent patients. Southeast

Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2013;44(2):143-9. PMid:23691621

- Bain BJ. Dyserythropoiesis in visceral leishmaniasis. American J Hematol 2010;85(10):781 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21787 PMid:20652969

- Temiz

F, Gurbuz BB, Leblebisatan G, Ozkan A, Canoz PY, Harmanogullari S,

Gezer H, Tumogor G, Turgut M. An association of leishmaniasis and

dyserythropoiesis in children. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2014; 30

(1):19-21 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-012-0189-0 PMid:24554815 PMCid:PMC3921338

- Bourdoiseau

G, Bonnefont C, Magnol JP, Saint-Andre I, Chabanne L (1997) Lymphocyte

subset abnormalities in canine leishmaniasis. Vet ImmunolImmunopathol

1997; 56: 345–351 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-2427(96)05768-6

- Reis

AB, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Giunchetti RC, Guerra LL, Carvalho MG, et al.

Phenotypic features of circulating leucocytes as immunological markers

for clinical status and bone marrow parasite density in dogs naturally

infected by Leishmania chagasi. Clin Exp Immunol 2006;146: 303–311 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03206.x PMid:17034583 PMCid:PMC1942052

- Scalzone

M, Ruggiero A, Mastsngelo S, Trombatore G, Ridola V, Maurii P, Riccardi

R. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and visceral leishmaniasis in

children: case report and systematic review of literature. J Infect Dev

Ctries 2016;10(1):103-8 https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.6385 PMid:26829545

- Jeronimo

SMB, de Queiroz Sousa A, Pearson RD. Leishmaniasis In: Tropical

infectious diseases: principles, pathogens and practice, Guerrant, RL,

Walker, DH, Weller, PF (Eds), Churchill Livingstone Elsevier,

Edinburgh, Scotland 2006. p. 1095-1113.

- Houweling

TA, Karim-Kos HE, Kulik Mc, Stolk WA, Haagsama JA, Lenk EJ, Richardus

JH, de Vlas SJ. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Neglected Tropical

Diseases: A Systematic Review. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2016;6(2):146-8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004546

- Nicolato

RC, Abreu RT, Roatt BM, Aguiar-Soares RDO, Reis LES, Carvalho MG,

Carneiro CM, Giunchetti RC et al. Clinical Forms of Canine Visceral

Leishmaniasis in Naturally Leishmania infantum–Infected Dogs and

Related Myelogram and Hemogram Changes. PLOS ONE 2013;8(12): e82947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082947 PMid:24376612 PMCid:PMC3871677

- Tryphonas

L, Zawidzka Z, Bernard MA, Janzen EA. Visceral leishmaniasis in a dog:

clinical, hematological and pathological observations. Can J Comp Med

1997;41: 1–12.

- Salpnickova

M, Volkova V, Cepickova M, Kobets T, Sima M, Svobodova M et al.

Gene-specific sex effects on eosinophil infiltration in leishmaniasis

Biology of Sex Differences 2016; 7:59.

- Dhingra

KK, Gupta P, Saroha V, Setia N,Khurana N, Singh T. Morphological

findings in bone marrow biopsy and aspirate smears of visceral Kala

Azar: A review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2010; 53 (1): 96-100. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.59193 PMid:20090232

[TOP]

.

.