Annita Kolnagou1,2, Christina N Kontoghiorghe1 and George J Kontoghiorghes1

1 Postgraduate Research Institute of Science, Technology, Environment and Medicine Limassol, Cyprus.

2 Thalassaemia Unit, Paphos General Hospital, Paphos, Cyprus.

Corresponding

author: George

J. Kontoghiorghes, Postgraduate Research Institute of Science,

Technology, Environment and Medicine, 3 Ammochostou Street, Limassol

3021, Cyprus. Tel: +35726272076; Fax: +35726272076. E-mail:

kontoghiorghes.g.j@pri.ac.cy

Published: October 18, 2017

Received: July 19, 2017

Accepted: October 8, 2017

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2017, 9(1): e2017060 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2017.060

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

We

report two separate episodes of transfusion-related acute lung injury

(TRALI) in two thalassaemia patients who received red blood cell

transfusions from the same multiparous donor. Both cases had the same

symptomatology and occurred within 60 minutes of transfusion. The

patients presented dyspnoea, sweating, fatigue, dizziness, fever, and

sense of losing consciousness. The chest x-ray showed a pulmonary

oedema-like picture with both lungs filled with fluid. The patients

were treated in the intensive therapy unit. They were weaned off the

ventilator and discharged following hospitalization 7 and 9 days

respectively. The TRALI syndrome was diagnosed to be associated with

HLA-specific donor antibodies against mismatched HLA-antigens of the

transfused patients. Haemovigilance improvements are essential for

reducing the morbidity and mortality in transfused patients. Blood from

multiparous donors should be tested for the presence of IgG HLA-Class I

and -Class II antibodies before being transfused in thalassaemia and

other chronically transfused patients.

|

Introduction

The

major adverse events caused by transfusions are mainly related to the

transfer of non matched blood components, acute and delayed reactions,

transmission of viral or bacterial infections, transfusion-related

acute lung injury (TRALI) etc.[1-5]

To minimise

the risk of adverse events, the donated blood is thoroughly screened

for antibodies, viruses and other risk factors before storage and

transfusion.

In the case of TRALI which occurs in 0.04-0.16 % of

transfusions, almost all types of blood products have been associated

with adverse events, such as packed red blood cells (RBC), fresh frozen

plasma and platelets.[1,2] TRALI has been estimated to

be the third cause of transfusion-related mortality with current

mortality rates ranging in the patients affected between 5 to 25%.[4,6]

About

two-thirds of the TRALI incidences are thought to be immune-mediated

and involve mainly the passive transfusion of leucocyte antibodies in

blood products.[7] Antibody-mediated TRALI is an

important cause of transfusion-associated morbidity and is the leading

cause of transfusion-related mortality.[7]

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Class I, HLA-Class II or

neutrophil-specific antibodies, particularly HNA-3a have been

implicated in most of the reported cases of TRALI.[3,8]

The

mechanism for TRALI in thalassaemia involves mainly the transfer of

blood donor antibodies through contamination of the transfused RBC and

reaction with the anti-HLA antigens of lymphocytes of the recipient,

affecting mainly the lung endothelium of the recipient causing

pulmonary oedema. Blood donor antibodies are particularly prevalent in

some categories of blood donors such as multiparous women, where

antibodies are formed in response to sensitisation from foetal blood

infiltration during multiple pregnancies.[3]

Case Report

Approval

of the report of the cases was obtained from the committee of clinical

studies of the Ministry of Health and the Bioethics Committee of

Cyprus. The patients gave their informed consent for reporting the

study.

Two male thalassaemia major patients of 28 (A) and 31 (B)

years had separate episodes of the TRALI syndrome in 2004 and 2011

respectively, which were caused as a result of the transfusion of

packed RBC from the same multiparous woman blood donor. During the

period of TRALI, patient A was splenectomised with a mean rate of RBC

transfusions of 186 ml/kg/year while patient B had splenomegaly

(19x11cm) and was hypertransfused with a mean rate of RBC transfusions

of 366 ml/kg/year. Patient A was non-iron loaded with serum ferritin

246 μg/l, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2* of the heart 23.4 ms and

liver 17.0 ms and other clinical complications included osteopenia,

hypogonadism and cholelithiasis. Patient B was iron loaded with serum

ferritin 2790 μg/l, MRI T2* of the heart 40.9 ms and liver 5.9 ms and

in addition to cholecystectomy and splenomegaly, clinical complications

included osteopenia and hypothyroidism. Patient A was receiving

deferiprone and patient B deferoxamine for the treatment of iron

overload, as well as other drugs for the treatment of other clinical

complications of the underlying disease.

The diagnosis of the

TRALI syndrome in each case was generally difficult because of the

rarity of the complication, number of symptoms and the timing of the

event. Despite the diagnostic difficulties, the symptoms in both cases

were the same (Table 1). A

difference in the timing of the initiation of the clinical symptoms due

to TRALI was observed between the two patients. In the patient A, the

acute respiratory distress symptoms began in about 10-15 minutes after

the initiation of the transfusion involving 15-20 ml from one unit of

320 ml of packed RBC from one blood donor. In the patient B, the

symptoms began at home at about 60 minutes following the transfusion of

two RBC units of 300 ml and 280 ml from two different blood donors

respectively.

|

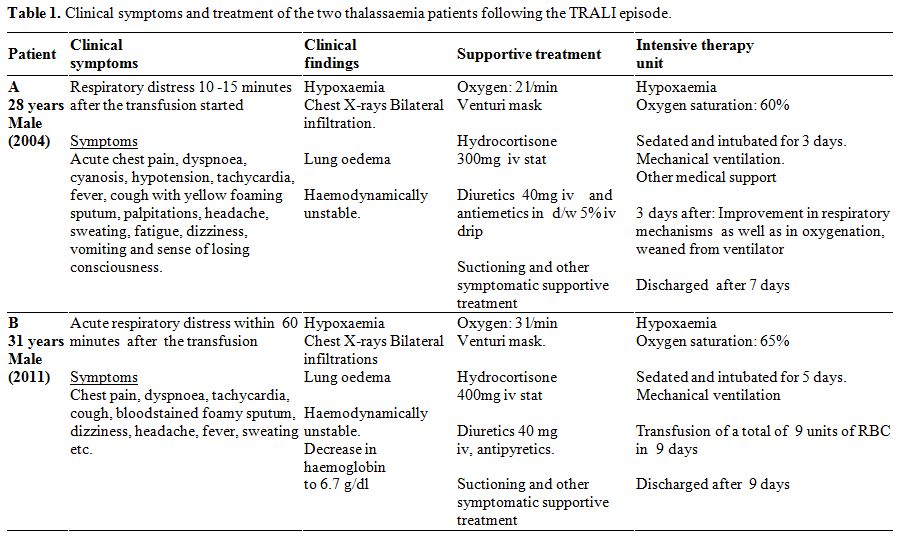

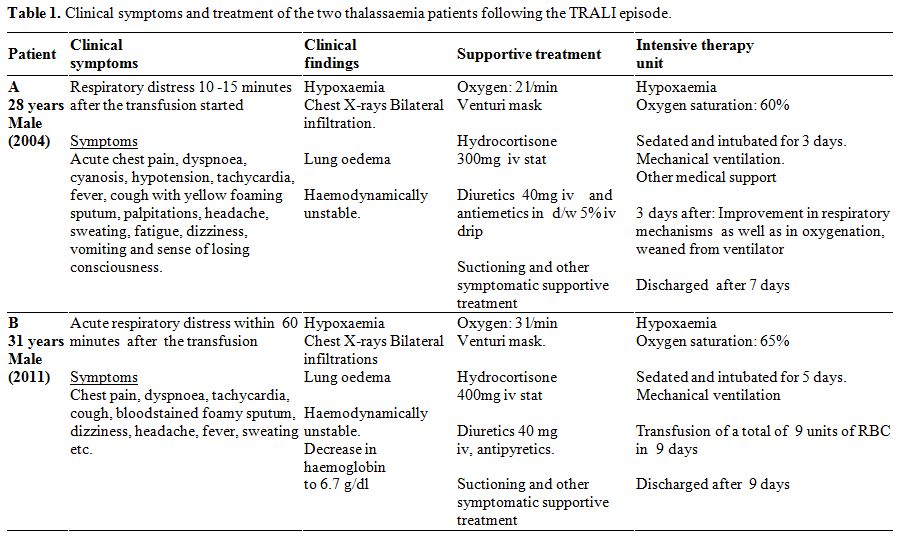

Table

1. Clinical symptoms and treatment of the two thalassaemia patients following the TRALI episode. |

In

both cases, the patients presented a number of symptoms including

dyspnoea, sweating, fatigue, dizziness, fever, and sense of losing

consciousness (Table 1).

Clinical and laboratory investigations indicated the presence of

hypoxaemia with oxygen saturation in patients A and B of less than

60% and 65% respectively, increased respiratory rate, low blood

pressure and increased pulse rate. The chest x-ray showed pulmonary

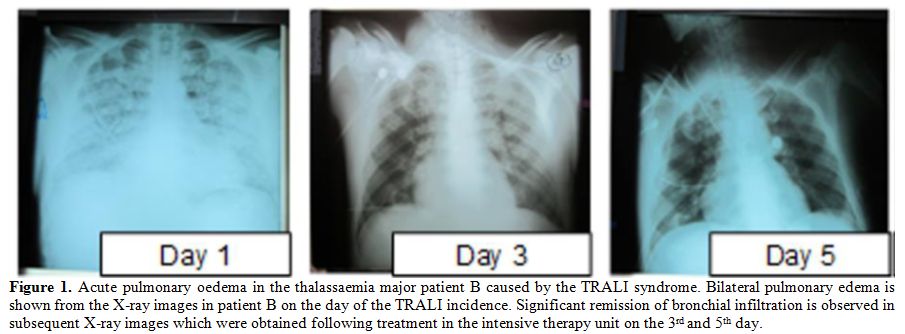

oedema with both lungs filled with fluid (Table 1, Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Acute pulmonary oedema in the

thalassaemia major patient B caused by the TRALI syndrome. Bilateral

pulmonary edema is shown from the X-ray images in patient B on the day

of the TRALI incidence. Significant remission of bronchial infiltration

is observed in subsequent X-ray images which were obtained following

treatment in the intensive therapy unit on the 3rd and 5th day. |

Supportive

treatment included the administration of oxygen, adrenaline, cortisone,

diuretics, suctioning and other symptomatic treatment before admission

to the intensive therapy unit, where further deterioration of lung

function was observed which led to sedation and intubation on a

mechanical ventilator (Table 1).

Improvement in the respiratory parameters including oxygenation,

remission of the lung oedema, as well as RBC transfusions and other

medical support allowed the patients to be weaned off the ventilator

and discharged from the intensive therapy unit following the

hospitalisation of a total of 7 days and 9 days for patients A and B

respectively.

In both cases, the laboratory findings suggested

the cause of an allergic reaction as a result of the transfusion. In

the patient A, high lymphocyte count (7.83%) was detected in the

transfused packed RBC. Furthermore, on the first day of the TRALI

episode the T cell marker count of CD5 and CD7 increased to 48% and 54%

respectively, the anti-RBC antibodies to 48% and the anti-HLA

antibodies to 20%. On the second day following the episode the CD5 and

CD7 counts decreased to 25% and 28% respectively, the anti-RBC

antibodies to 20% and the anti-HLA antibodies remained unchanged at

20%.

In the case of patient B, HLA-typing was performed on both

the patient’s and the blood donors’ samples, as well as HLA-specific

antibody testing on the donor's serums. A multiparous woman blood donor

was found to be positive for the presence of IgG HLA-Class I and -Class

II antibodies against the following mismatched antigens of patient B:

HLA -A30, -A33, -B8, -DR4, and -DR17. The complement cytotoxicity

cross-match against the T and B patient lymphocytes was also positive.

The

TRALI syndrome was diagnosed in both cases as a result of the presence

of residual plasma and leucocytes in the RBC transfusion, which was

associated with HLA-specific antibodies of the multiparous woman blood

donor against mismatched HLA-antigens of the transfused patients A and

B.

The multiparous blood donor related to the TRALI incidences was

a mother of four children and had in total six pregnancies. Following

the first incidence of TRALI, she was advised to terminate blood

donations. However, seven years later she ignored the earlier advice

and donated blood which resulted in the second TRALI incidence. Discussion

To

our knowledge, these are the first cases of thalassaemia patients who

had a TRALI episode originating from the same blood donor. It appears

that despite significant efforts to eliminate or minimise the risks of

toxicity associated with transfusions, the immunological toxic side

effects are evident, especially in chronically transfused patients.

Further improvements in haemovigilance are essential for reducing the

morbidity and mortality associated with transfusions.

In the

case of thalassaemia major, chronic transfusions cause alloantibody

formation in response to the transfused RBC. In one study it was

estimated that 22% of the thalassaemia patients have alloantibodies,

with a higher rate in splenectomised (36%) compared to

non-splenectomised (13%) patients.[9,10] Similarly,

autoantibodies (Coombs +ve) are found in about 25% and autoantibodies

with alloantibodies in 44%, which is higher in splenectomised

thalassaemia patients (56%).[9,10] The presence of

autoantibodies and alloantibodies appear to increase with age due to

exposure to more antigens from different blood donors as a result of

the increase in the number of transfusions. It is mainly observed in

older thalassaemia patients, especially when considering that with the

recent introduction of improved treatments life expectancy has

increased and thalassaemia patients are living longer and approaching

normal lifespan.[11]

Allergic and

febrile reactions are common side effects of RBC transfusions in

thalassaemia patients. Similarly, other common side effects include

delayed haemolytic reactions and bacterial or viral (Hepatitis B and C)

infections.[12]

Despite that TRALI is a

rare syndrome, the symptoms are rapid and life-threatening. The

patients affected by TRALI should be urgently diagnosed and receive the

appropriate emergency treatment. Recipient predisposition and number of

other factors appear to affect the aetiology and prognosis of

individual patients with TRALI.[3,13,14]

In

relation to haemovigilance and TRALI, the findings of this study

signify and suggest that additional steps should be taken about the

TRALI prevention measures which are commonly adopted, i.e. the

prevention from plasma donation of female donors with previous

pregnancies or any other donors who had received transfusions. In

particular, in the light of the present findings, the permission for

RBC donation of individuals from the above groups should be

reconsidered since it may prove ineffective from preventing TRALI in

similar cases.[2-4,13,14]

Within

the context of hemovigilance, there is also a need for the preparation

of further guidelines at the national and international level to

minimise the incidence of TRALI. For example, a male-only strategy for

RBC or other blood product donation for transfusions could decrease the

incidence of TRALI in thalassaemia and other similar categories of

patients.[14] Similarly, RBC and other blood

component samples from multiparous women donors should be thoroughly

tested for the presence of IgG HLA-Class I and -Class II antibodies and

excluded from blood donation in thalassaemia or other high-risk

categories of patients.[3,4,13,14]

Acknowledgements

This

work was supported by internal funds of the Postgraduate Research

Institute of Science, Technology, Environment and Medicine. We would

like to thank Drs A. Varnavidou-Nicolaidou and D. Voniatis of the

Nicosia General Hospital for the immunological studies and other staff

of the Paphos General Hospital involved in the medical care of the two

patients.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Evdoxia Mantilari Kontoghiorghe, who passed away in February 2017.

References

- Webert KE, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfus Med Rev. 2003;17:252-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-7963(03)00039-7

- Teofili

L, Bianchi M, Zanfini BA, Catarci S, Sicuranza R, Spartano S et al.

Acute lung injury complicating blood transfusion in post-partum

hemorrhage: incidence and risk factors. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2014;6:e2014069. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2014.069 PMid:25408855 PMCid:PMC4235434

- Peters

AL, Van Stein D, Vlaar AP. Antibody-mediated transfusion-related acute

lung injury; from discovery to prevention. Br J Haematol.

2015;170:597-614. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13459 PMid:25921271

- Moalic

V, Vaillant C, Ferec C. Transfusion related acute lung injury (TRALI):

an unrecognised pathology. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2005;53:111-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patbio.2004.06.001 PMid:15708656

- Bulanov AIu. Transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI): obvious and incomprehensible. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2009;5:48-52

.

.

- Porretti

L, Cattaneo A, Coluccio E, Mantione E, Colombo F, Mariani M.

Implementation and outcomes of a transfusion-related acute lung injury

surveillance programme and study of HLA/HNA alloimmunisation in blood

donors. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:351-359. PMid:22395353 PMCid:PMC3417735

- Muller

MC, Porcelijn L, Vlaar AP. Prevention of immune-mediated

transfusion-related acute lung injury; from bloodbank to patient. Curr

Pharm Des. 2012; 18: 3241-3248. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612811209023241 PMid:22621273

- Keller-Stanislawski

B, Reil A, Günay S, Funk MB. Frequency and severity of

transfusion-related acute lung injury- German haemovigilance data

(2006-2007). Vox Sang. 2010;98:70-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01232.x PMid:19671122

- Singer

ST, Wu V, Mignacca R, Kuypers FA, Morel P, Vichinsky EP.

Alloimmunization and erythrocyte autoimmunization in

transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients of predominantly asian

descent. Blood. 2000;96:3369-3373. PMid:11071629

- Chaudhari CN. Red Cell Alloantibodies in multiple transfused thalassaemia patients. MJAFI 2011; 67: 34-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-1237(11)80008-0

- Kolnagou

A, Kontoghiorghe CN, Kontoghiorghes GJ. Transition of Thalassaemia and

Friedreich ataxia from fatal to chronic diseases. World J Methodol.

2014;4:197-218. https://doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v4.i4.197 PMid:25541601 PMCid:PMC4274580

- Prati

D. Benefits and complications of regular blood transfusion in patients

with beta-thalassaemia major. Vox Sang.2000;79:129-137. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1423-0410.2000.7930129.x PMid:11111230

- Silliman

CC, Boshkov LK, Mehdizadehkashi Z, Elzi DJ, Dickey WO, Podlosky L et

al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: epidemiology and a

prospective analysis of etiologic factors. Blood. 2003;101: 454-462. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-03-0958 PMid:12393667

- Lucas

G, Win N, Calvert A, Green A, Griffin E, Bendukidze N, et

al.Reducing the incidence of TRALI in the UK: the results of screening

for donor leucocyte antibodies and the development of national

guidelines.Vox Sang. 2012;103:10-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01570.x PMid:22150747

[TOP]

.

.