Alessia Castellino1, Stefano Guidi2, Chiara Maria Dellacasa3, Antonella Gozzini2, Irene Donnini2, Chiara Nozzoli2, Sara Manetta3, Semra Aydin1, Luisa Giaccone3, Moreno Festuccia3, Lucia Brunello3, Enrico Maffini3, Benedetto Bruno3, Ezio David4 and Alessandro Busca3.

1 A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Dipartimento di Oncologia, Ematologia, Torino, Italy.

2 SODc Terapie Cellulari e Medicina Trasfusionale, AOU Careggi, Firenze.

3

A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Dipartimento di

Oncologia, SSD Trapianto allogenico di cellule staminali, Torino, Italy.

4 S.C. Anatomia Patologica 1, A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino.

Corresponding

author: Castellino Alessia MD, A.O.U.

Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Dipartimento di

Oncologia, Ematologia, Torino, Italy. Corso Bramante 88, 10126 Torino.

Tel: +39 0116335359 FAX: +39 011 6335759. E-mail:

acastellino@cittadellasalute.to.it

Published: January 1, 2018

Received: August 2, 2017

Accepted: November 5, 2017

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018001 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.001

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Hepatic

Veno-Occlusive Disease (VOD) is a potentially severe complication of

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Here we report two

patients receiving an allogeneic HSCT who developed late onset VOD with

atypical clinical features. The two patients presented with only few

risk factors, namely, advanced acute leukemia, a myeloablative

busulphan-containing regimen and received grafts from an unrelated

donor. The first patient did not experience painful hepatomegaly and

weight gain and both patients showed only a mild elevation in total

serum bilirubin level. Most importantly, the two patients developed

clinical signs beyond day 21 post-HSCT. Hepatic transjugular biopsy

confirmed the diagnosis of VOD. Intravenous defibrotide was promptly

started leading to a marked clinical improvement. Based on our

experience, liver biopsy may represent a useful diagnostic tool when

the clinical features of VOD are ambiguous. Early therapeutic

intervention with defibrotide represents a crucial issue for the

successful outcome of patients with VOD.

|

Introduction

Veno-occlusive

disease (VOD), also known as sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS), is

a potentially life-threatening complication of hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation (HSCT).[1] The diagnosis of VOD is

primarily based on clinical criteria defined almost 20 years ago,

including the triad of painful hepatomegaly, jaundice and fluid

retention.[2-4] This observation could at least

partially explain the highly variable incidence of VOD reported in the

literature, ranging from 8% to 14%. VOD usually develops within 20-30

days after HSCT. However, few cases of late-onset VOD have been

reported.[5] According to this observation, the

European Group for Bone marrow Transplantation (EBMT) recently endorsed

the revised diagnostic criteria for VOD/SOS, which now include either a

classical form of VOD and a late-onset variant (Table 1).[6]

Here we describe two HSCT recipients who developed late-onset VOD with atypical clinical features.

|

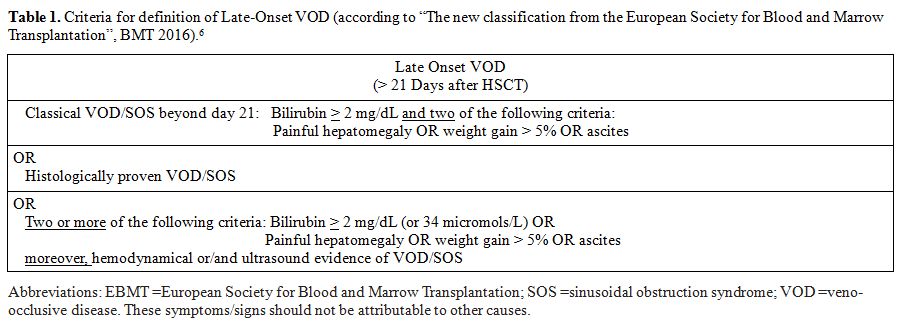

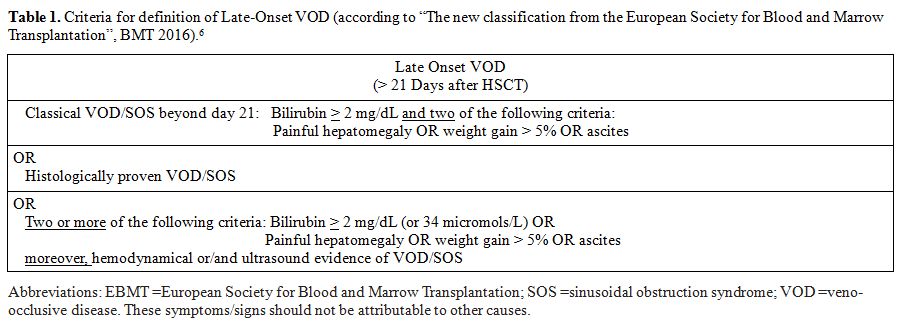

Table

1. Criteria for definition of Late-Onset VOD (according to “The new

classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation”, BMT 2016).[6] |

Case 1

A

55-year-old male was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in May 2015.

He failed to achieve the complete remission (CR) after two induction

chemotherapy courses with high dose cytarabine, idarubicin and

etoposide and salvage treatment with fludarabine and idarubicin. The

presence of a matched unrelated donor in the International Marrow Donor

Registries prompted us to proceed with an allogeneic HSCT following a

“sequential” conditioning regimen. The patient was initially treated

with mitoxantrone (6 mg/sqm/day), etoposide (80 mg/sqm/day) and

cytarabine (1 g/sqm/day for four days), followed, 10 days later, by a

conditioning which included i.v. Busulphan (3.2 mg/kg/day) and

Fludarabine (50 mg/mq/day) for four days and the infusion of mobilized

donor peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC). Graft-vs.-Host disease (GVHD)

prophylaxis consisted of anti-thymocyte globulin, cyclosporine and a

short course of methotrexate. An absolute neutrophil count higher than

0.5x109/L and a platelet count higher

than 20.000/mcl were achieved on day +13. On day +33, the patient

suddenly showed abdominal distension with ascites, increase in liver

enzymes (AST 391 U/l, ALT 245 U/l) and in total bilirubin (1.2 mg/dL)

and signs of liver and renal insufficiency (INR 1.43; aPTT 65.5’’;

serum creatinine value 3.04 mg/dL). The patient did not present

either painful hepatomegaly or weight gain >2%, or signs of

intestinal or cutaneous acute GVHD. Viral hepatitis was ruled out by

microbiological testing. Ultrasonography showed normal liver

parenchyma, regular biliary tract, moderate splenomegaly (15 cm) with

ascites and right pleural effusion. Doppler exam ruled out portal vein

thrombosis but showed increased portal vein diameter (10 mm) suggestive

of portal hypertension. Paracentesis was performed and showed presence

of transudate fluid (serum albumin =3 mg/dL, ascites albumin 1.5 mg/dL,

serum-ascites albumin ratio=2).

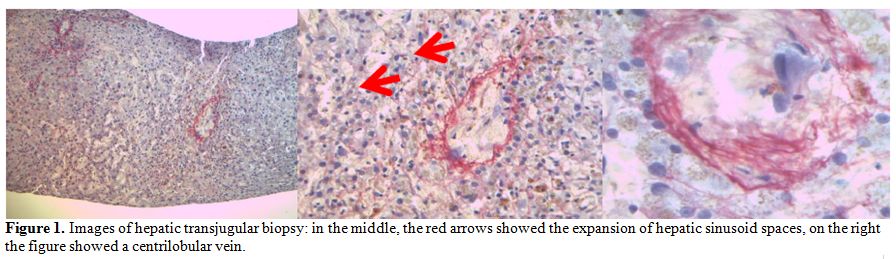

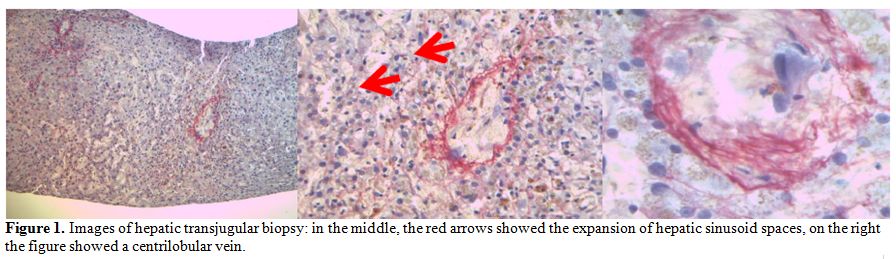

Given that clinical symptoms and

laboratory tests did not allow to discriminate between VOD, acute GVHD,

toxicity or infective causes, a hepatic transjugular biopsy was

performed. Histology studies showed the expansion of the hepatic

sinusoid spaces, with gaps in the sinusoidal barrier which were highly

suggestive of hepatic VOD in the light of the involvement of zone 3,

zone 2 and partially zone 1 of the hepatic acinus (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Images of hepatic transjugular

biopsy: in the middle, the red arrows showed the expansion of hepatic

sinusoid spaces, on the right the figure showed a centrilobular vein |

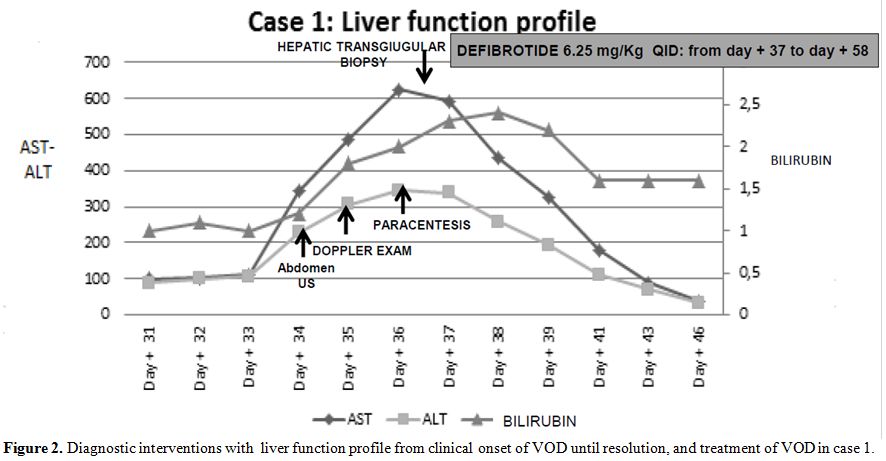

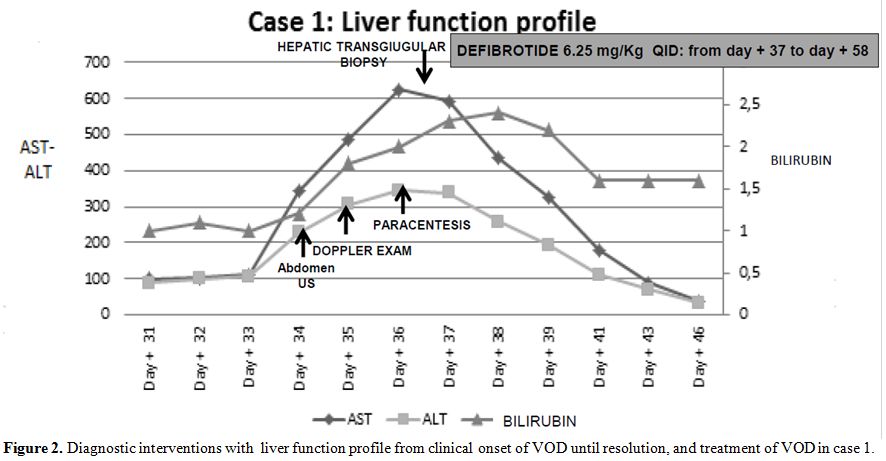

Intravenous

defibrotide was started at the dose of 6.25 mg/kg QID on day +37 for 21

days, along with ancillary therapy including albumin replacement and

low dose diuretics; nonsteroids have been administered. Two-three days

after the beginning of defibrotide, the patient showed a marked

clinical improvement with gradual improvement and normalization of

liver and renal function tests (Figure 2).

One week after the beginning of defibrotide, the patient developed

hemorrhagic cystitis, treated with 2 bladder instillations of

hyaluronic acid which led to progressive improvement and complete

resolution upon regular discontinuation of defibrotide after 21 days of

treatment. Hemorrhagic cystitis did not require an earlier

discontinuation of defibrotide. During the treatment course, platelet

count remained low between 10.000 to 20.000/mmc even with transfusion

support. The patient was discharged on day +76 in complete remission of

his underlying disease on low doses of cyclosporine.

|

Figure 2. Diagnostic interventions with

liver function profile from clinical onset of VOD until resolution, and

treatment of VOD in case 1. |

Case 2

A

46-year old male was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia - normal

karyotype, FLT3, and NPM1 wild-type - in May 2015. The patient was

treated with idarubicin plus etoposide and cytarabine with no

hematologic response. Complete remission was subsequently obtained with

a course of high-dose cytarabine, followed consolidation with 2

additional courses of high-dose cytarabine. An unrelated marrow donor

search was started and a partially (one-antigen mismatched) HLA-matched

donor was identified. The patient received mobilized donor HSCT after a

conditioning regimen with Thiotepa (5 mg/kg/day for 2 days), Busulphan

(3,2 mg/kg/day for 3 days) and Fludarabine (50 mg/kg/day for 3 days).

GvHD prophylaxis included cyclosporine, short course methotrexate, and

anti-thymocyte globulin ATG (2,5 mg/kg/day for 3 days). Neutrophil and

platelet engraftment occurred on day +14 and +12 respectively. The

patient experienced a transient skin rash suggestive of grade I acute

GVHD on day +19, and 3 episodes of CMV reactivation on days +27, +43

and +82 successfully treated with preemptive valganciclovir and

immunoglobulins.

The patient was readmitted because of severe

anemia and thrombocytopenia (Hb 5,8 gr/dl; platelet 5000/ul) and

complaints of right abdominal pain with melena on day +89.

Significant weight gain (+7 kg) along with abdominal distension and

anasarca were observed on day +91. Laboratory exams showed total

bilirubin 3,30 mg/dl, AST/ALT 140/164 UI, GGT 725 Ul, INR 1,7; aPTT

41,3”, serum creatinine 2,0 mg/dl; platelet count was 20.000/mmc. An

abdominal CT scan revealed ascites and hepatic veins compression.

Transjugular measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient showed

severe sinusoidal portal hypertension with a significant

transhepatic/caval gradient diagnostic for severe VOD. Transjugular

liver biopsy showed sinusoidal dilation and bleeding with erythrocytes

in the Disse space, and significant iron overload. Histology studies

were consistent with severe VOD.

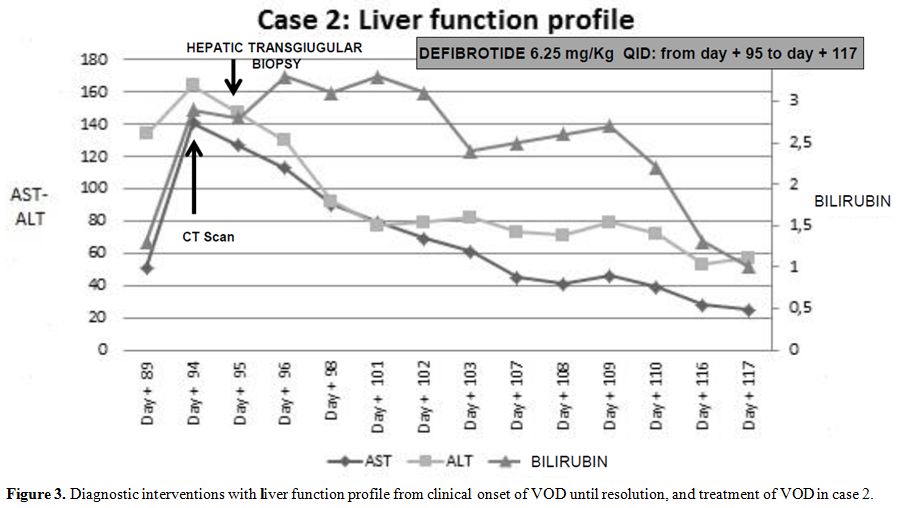

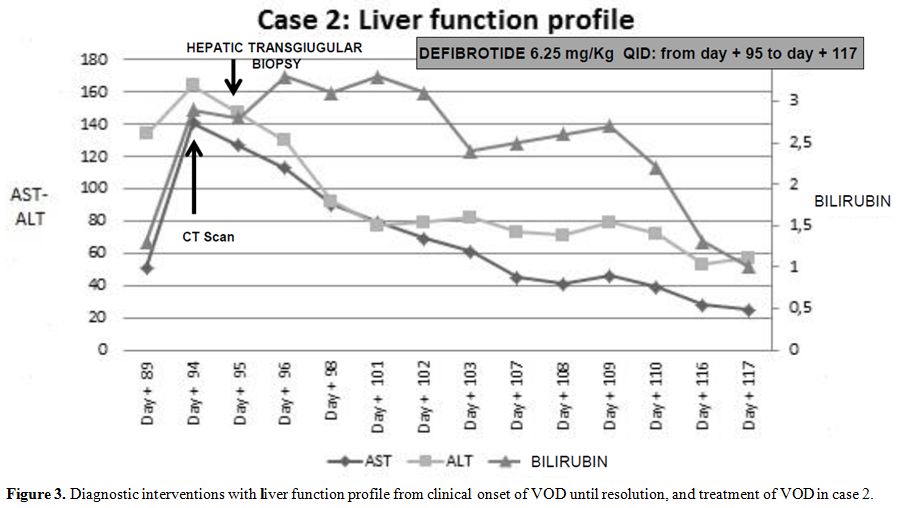

Intravenous defibrotide was promptly started at the dose of 6.25 mg/kg QID for 22 days.

Ancillary

therapy included plasma and red blood cells transfusions, no steroid

have been administered. A complete and sustained response was achieved.

The patient was discharged on day +121. The patient is currently alive,

188 days after transplant, with normal liver function, no evidence

of GvHD, or any other relevant clinical complication. A bone

marrow aspirate showed complete remission of his underlying disease.

|

Figure 3. Diagnostic interventions with

liver function profile from clinical onset of VOD until resolution, and

treatment of VOD in case 2. |

Discussion

Recognition

of potential risk factors for VOD is a key point for early diagnosis

and prompt therapeutic intervention. Recently, the EBMT group has

categorized these risk factors as transplant-, hepatic-, patient- and

disease-related.[7-9] Interestingly, our patients

presented with only a few risk factors, namely, advanced acute

leukemia, a myeloablative busulphan-containing conditioning and an

unrelated donor. Moreover, both patients did not show the typical

clinical VOD features described by the Seattle[2-3] and Baltimore[4]

criteria. In particular, the first patient did not experience either

painful hepatomegaly or weight gain, and only a mild elevation in total

serum bilirubin level was observed after the development of ascites,

while the second patient showed only mild hyper-bilirubinemia

concurrent with painful hepatomegaly and significant weight gain. Most

importantly, both patients developed clinical signs beyond day 21

post-HSCT (on days +33 and +89 respectively). In this respect, it

should be emphasized that the EBMT consensus6 has now recognized

the existence of a “late onset” VOD, defined with less stringent

diagnostic criteria and where hyper-bilirubinemia should no longer be

mandatory for diagnosis. Overall, in these two patients, the short time

between the onset of clinical symptoms and the final diagnosis, and the

higher than 5 fold increase in transaminases combine to diagnose a

severe form of VOD by the new EBMT criteria (Table 1)

Both the British guidelines[10]

and the EBMT recommendations indicate that liver biopsy should be

reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of VOD is unclear,

and there is an urgent need to rule out other possible causes of liver

dysfunction. In our experience, a transjugular liver biopsy was safe

despite severe thrombocytopenia and, most importantly, was conclusive

for the diagnosis of VOD ruling out drug toxicities, viral infections,

sepsis or GVHD.[11-13] In keeping with our findings, Kis et al. reported only 1.8% of major complications during 166 transjugular liver biopsies.[14]

Defibrotide

is the only agent approved for the treatment of VOD in Europe.

Defibrotide has been shown to have antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory

properties and may promote revascularization inducing endothelial cell

proliferation and angiogenesis.[15] In our patients,

the combination of clinical features and histology studies prompted us

to start defibrotide only a few days after the onset of symptoms. Our

experience strengthens the observation reported by Richardson et al.,[16]

that the timely administration of defibrotide may represent a crucial

issue for the successful outcome of patients with VOD. Sixty % of

patients were alive when defibrotide was started within 2 days from the

onset of symptoms as compared with 14% when treatment was delayed and

started after 7 days. Similar results were reported by Corbacioglu et

al.[17] Our patients began defibrotide treatment

within 7 days from the onset of symptoms but within 1 day from the

histological diagnosis. They did not fall exactly in the early

treatment category. Nevertheless, defibrotide has been initiated within

7 days, representing the crucial threshold to achieve a good outcome.

Phase 2 and 3 studies[18-22] demonstrated that

defibrotide was generally well tolerated with manageable toxicity.

Hemorrhagic complications were reported as the most frequent adverse

event. Hemorrhagic cystitis, which occurred in one of our patients, is

a common complication in HSCT recipients. Though other causes may have

been involved, we could not rule out that it may have been related to

defibrotide treatment given its prompt resolution upon drug

discontinuation.[22]

Conclusions

VOD

should be considered in the differential diagnosis of HSCT recipients

who present with unexplained liver injuries, ascites and/or MOF. Liver

biopsy may represent a useful diagnostic tool when the clinical

criteria for VOD are not entirely fulfilled. Early therapeutic

intervention with defibrotide may improve the clinical outcomes of

these patients.

References

- Carreras E, et al. Veno-occlusive disease of the liver after hemopoietic cell transplantation. Eur J Haematol 2000;64: 281-291. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.9r200.x PMid:10863974

- McDonald,

G.B., Hinds, M.S., Fisher, L.D., et al. Veno-occlusive disease of the

liver and multiorgan failure after bone marrow transplantation: a

cohort study of 355 patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 1993; 118,

255-267. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-4-199302150-00003 PMid:8420443

- Jones,

R.J., Lee, K.S., Beschorner, W.E., et al. Venoocclusive disease of the

liver following bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation, 1987;44,

778-783. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-198712000-00011 PMid:3321587

- Lee,

J.L., Gooley, T., Bensinger, W., et al. Veno-occlusive disease of the

liver after busulfan, melphalan, and thiotepa conditioning therapy:

incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Biology of Blood and Marrow

Transplantation, 1999;5, 306-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1083-8791(99)70006-6

- Coppell

JA, Richardson PG, Soiffer R, Martin PL, Kernan NA, Chen A et al.

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease following stem cell transplantation:

incidence, clinical course, and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant

2010;16: 157-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.024 PMid:19766729 PMCid:PMC3018714

- Mohty

M, Malard F, Abecassis M, et al. Revised diagnosis and severity

criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in

adult patients: a new classification from the European Society for

Blood and Marrow Transplantation. BMT 2016, 1-7.

- Bearman

SI, et al. The syndrome of hepatic veno-occlusive disease after marrow

transplantation. Blood 1995; 85:3005-20. PMid:7756636

- Carreras

E, Bertz H, Arcese W, et al. Incidence and outcome of hepatic

veno-occlusive disease after blood or marrow transplantation: A

prospective cohort study of the European Group for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation: European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

Chronic Leukemia Working Party. Blood 1998;92:3599-604

PMid:9808553

- Cesaro,

S., Pillon, M., Talenti, E., et al. A prospective survey on incidence,

risk factors and therapy of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in children

after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica, 2005;90,

1396-1404. PMid:16219577

- Dignan

FL, Wynn RF, Hadzic N, et al. BCSH/BSBMT guideline: diagnosis and

management of veno-occlusive disease (sinusoidal obstruction syndrome)

following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. BJH 2013, 163,

444-457. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12558 PMid:24102514

- DeLeve,

L.D., Shulman, H.M. & McDonald, G.B. (2002) Toxic injury to hepatic

sinusoids: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (veno-occlusive disease).

Seminars in Liver Disease, 22, 27. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-23204 PMid:11928077

- Shulman,

H.M., Gown, A.M. & Nugent, D.J. (1987) Hepatic veno-occlusive

disease after bone marrow transplantation. Immunohistochemical

identi?cation of the material within occluded central venules. The

American Journal of Pathology, 127, 549-558 PMid:2438942

PMCid:PMC1899766

- Shulman,

H.M., Fisher, L.B., Schoch, H.G., Henne, K.W. & McDonald, G.B.

(1994) Veno-occlusive disease of the liver after marrow

transplantation: histological correlates of clinical signs and

symptoms. Hepatology, 19, 1171-1181. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840190515 PMid:8175139

- Kis

b, Pamarthi V, Fan C-M et al. Safety and Utility of Transjugular Liver

Biopsy in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. J Vasc Interv

Radiol 2013; 24:85-89 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.011 PMid:23200125

- Richardson,

P.G., Elias, A.D., Krishnan, A., et al. Treatment of severe

veno-occlusive disease with de?brotide: compassionate use results in

response without signi?cant toxicity in a high-risk population. Blood,

1998;92, 737-744. PMid:9680339

- Richardson

PG, Smith AR, Triplett BM, et al. Early Initiation of Defibrotide in

Patients with Hepatic Veno-Occlusive Disease/Sinusoidal Obstruction

Syndrome Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Improves Day

+100 Survival. ASH 2015. Poster Abs.

- Corbacioglu

S, Greil J, Peters C., et al. Defibrotide in the treatment of children

with veno-occlusive disease (VOD): a retrospective multicentre study

demonstrates therapeutic efficacy upon early intervention. BMT 2004;

Jan;33(2):189-95. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704329

- Bearman,

S.I., Anderson, G.L., Mori, M., Hinds, M.S., Shulman, H.M. &

McDonald, G.B. (1993) Venoocclusive disease of the liver: development

of a model for predicting fatal outcome after marrow transplantation.

Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11, 1729-1736. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.9.1729 PMid:8355040

- Chopra

R, Eaton JD, Grassi A, Potter M, Shaw B, Salat C, et al. Defibrotide

for the treatment of hepatic veno-occlusive disease: Results of the

European compassionate-use study. Br J Haematol 2000;111:1122-9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02475.x PMid:11167751

- Richardson

PG, Murakami C, Jin Z, Warren D, Momtaz P, Hoppensteadt D, et al.

Multi-institutional use of defibrotide in 88 patients after stem cell

transplantation with severe veno-occlusive disease and multisystem

organ failure: response without significant toxicity in a high-risk

population and factors predictive of outcome. Blood 2002;100:4337-43. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-04-1216 PMid:12393437

- Richardson

PG, Soiffer R, Antin J, Jin Z, Kurtzberg J, Martin P, et al.

Defibrotide (DF) for the treatment of severe veno-occlusive disease

(sVOD) and multi-organ failure (MOF) post SCT: Final results of a

multi-center, randomized, dose-finding trial. Blood 2006;108:178.

- Richardson

PG, Riches ML, Kernan NA, et al. Phase 3 trial of defibrotide for the

treatment of severe veno-occlusive disease and multi-organ failure.

Blood. 2016;127(13):1656-65. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-10-676924 PMid:26825712 PMCid:PMC4817309

[TOP]