Karin P.S. Langenberg-Ververgaert1, Ronald M. Laxer2. Angela S. Punnett1, L. Lee Dupuis3-5, Yaron Finkelstein6 and Oussama Abla1.

1 Division of

Hematology/Oncology, Department of Paediatrics, The Hospital for Sick

Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

2

Division of Rheumatology, Department of Paediatrics, The Hospital for

Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

3 Department of Pharmacy, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

4 Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

5 Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

6 The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Corresponding

author: Karin P.S. Langenberg-Ververgaert. Division of

Hematology/Oncology, Department of Paediatrics, The Hospital for Sick

Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1X8, Canada.

Tel: 416-813-7742. Fax: 416-813-5327. E-mail:

karin.langenberg@sickkids.ca

Published: March 1, 2018

Received: December 6, 2017

Accepted: January 15, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018019 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.019

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Familial

Mediterranean fever (FMF) has been associated with hematological

malignancies but has not been reported in association with Hodgkin

lymphoma (HL). We hereby describe the first pediatric patient with FMF

and stage IIA nodular sclerosis HL. She was treated with prednisone,

doxorubicin, vincristine and etoposide (OEPA) being on therapy with

colchicine. However, she suffered more than expected treatment-related

toxicity attributed either to chemotherapy (severe neutropenia) or

colchicine (Abdominal pains and diarrhoea). Colchicine had to be

discontinued. In the absence of colchicine, she tolerated very well the

second cycle of chemotherapy. Currently, she is in remission at 17

months after her HL diagnosis, and her FMF is under control with

colchicine without any signs of toxicity.

|

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a lymphoid malignancy that accounts for approximately 7% of childhood cancers in the United States.[1]

Five-year survival rates are 98% and 97% for the <15 years and 15–19

years age cohorts, respectively. Several risk factors have been

associated with developing HL, such as EBV infection,[2] primary immune deficiencies[3] and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS).[4]

Familial

Mediterranean fever (FMF) (OMIM 249100) is an autoinflammatory syndrome

that can be adequately treated in the majority of cases with

colchicine.[5] Clinically, FMF is characterized by

recurrent episodes of fever, serositis, arthritis, dermal

manifestations and long-term renal complications.[6]

The goals of FMF treatment are to prevent acute attacks, decrease the

subclinical inflammation between the attacks and to prevent the

development of amyloidosis. Colchicine suppresses pyrin oligomerization

and interferes with neutrophil migration. It also prevents cytoskeletal

changes that lead to pyrin inflammasome assembly. Alternative treatment

options, particularly for colchicine-resistant or intolerant patients

include interleukin-1 inhibitors such as anakinra and canakinumab.[7]

FMF has been reported in association with adult hematological

malignancies such as multiple myeloma, acute lymphoblastic and myeloid

leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes.[7-12]

However, this entity has not been reported in association with HL in

adults or children. We describe the first case of HL in a pediatric

patient with FMF, who developed myelotoxicity due to the combination of

colchicine with chemotherapy.

Case Presentation

A

6-year-old girl, of Turkish descent, presented with a 6-week history of

right posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. She had no recent history of

fever, night sweats or weight loss. Past medical history was

significant for FMF with a known M694V mutation in the MEFV gene (and

an r40w variant of unknown significance in the MVK gene), diagnosed at

age one year and well managed with colchicine 0.3 mg orally twice/day.

Complete blood count (CBC) showed white blood cell count 8.3 × 103/µl, hemoglobin 130 g/L, and platelet count 298,000/µl.

Lactate dehydrogenase was 850 IU/L, uric acid 174 umol/L and ESR 2

mm/h. An excisional biopsy of a cervical lymph node showed effacement

of the normal nodal architecture with a smaller population of large

atypical cells with large prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and

occasional classical diagnostic Reed-Sternberg cells.

Immunohistochemical stains revealed positivity for CD30, CD15 and PAX5.

The tumour cells were focally positive for CD3 and negative for ALK-1,

CD45 and CD20. In situ hybridization for EBV-EBER (where EBER is

Epstein–Barr encoding region) was positive in the majority of large

atypical cells. Staging included PET computerized tomography which

demonstrated localized hypermetabolic right cervical lymph nodes with

the absence of bulk disease. Therefore, the final diagnosis was stage

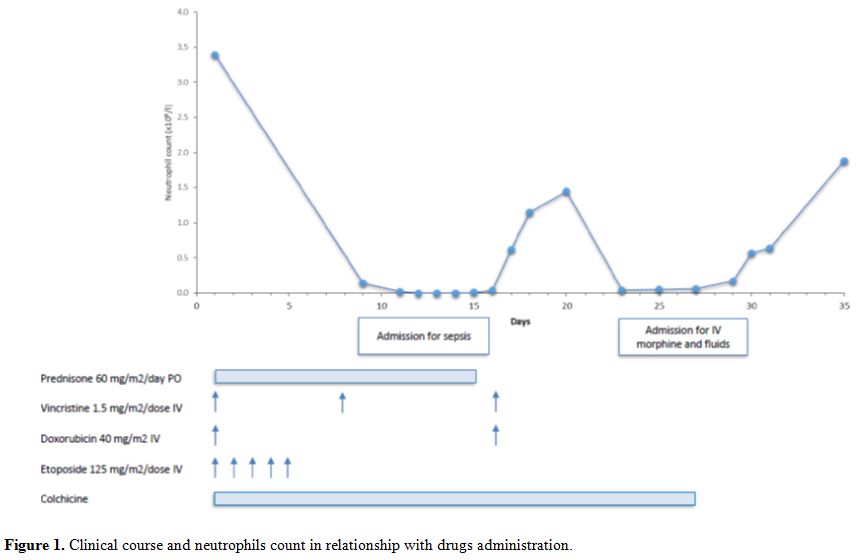

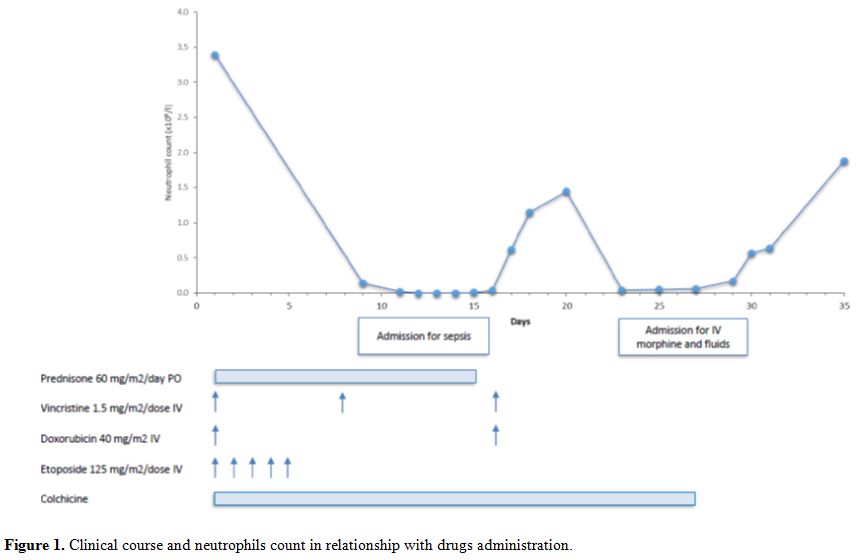

IIA classical Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular sclerosis subtype. The patient (Figure 1) was treated according to the local standard of care for low risk HL using 2 cycles of OEPA (vincristine 1.5 mg/m2/dose IV days 1, 8 and 15, etoposide 125 mg/m2/dose IV days 1-5, prednisone 60 mg/m2/day PO days 1–15, and doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 IV days 1 and 15) chemotherapy only.[13]

|

Figure 1. Clinical course and neutrophils count in relationship with drugs administration. |

Her

first treatment course was complicated by prolonged myelosuppression

including CTCAE grade 4 neutropenia, fever and severe abdominal pain.

She needed to be admitted on day 8 for clinical sepsis, requiring three

intravenous fluid boluses and antibiotics. Furthermore the second

infusion of Vincristine and Doxorubicin was postponed to Day 16. No

other signs of colchicine toxicity, such as bloody stool, renal failure

or disseminated intravascular coagulation were noted. Blood cultures

remained negative. She was discharged home after twelve days but needed

readmission on day 22 due to severe abdominal pain and loose stools,

treated with intravenous hydration and morphine for nine days. After

consultation with the Rheumatology service, colchicine was discontinued

from day 27 of cycle 1 onwards, to prevent possible interactions with

chemotherapy. Cycle 2 was started 36 days after start of cycle 1. She

tolerated this much better, without any complications and count

recovery within the expected timeframe. Clinical and radiographic

evaluations showed no evidence of disease at the end of therapy. The

patient currently remains in remission 17 months after completion of

therapy. Subsequently, she developed similar fever attacks and

colchicine was resumed at the same dose 3 months after completion of

chemotherapy. Her FMF has been well controlled since, without any signs

of colchicine toxicity. Discussion

Familial

Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autosomal recessive disorder, although

autosomal dominant and heterozygous patients have been reported as

well. It is characterized by recurrent self-limiting acute painful

attacks of fever and inflammation in the peritoneum or pleura,

arthritis, splenomegaly and skin rashes, lasting 12–72 hours.

Amyloidosis with renal failure is a complication and may develop

without overt crises.[6] Several sets of criteria have

been developed in order to classify the disease, such as the Tel

Hashomer criteria in adults and the modified criteria in childhood.[14-15]

The disease is associated with mutations in the MEFV gene, localized on

chromosome 16p13, encoding for the protein pyrin, which is involved in

the regulation of inflammation and apoptosis.[16] It

has an important role in the innate immune system and interacts with

caspase-1 and other inflammasome components to regulate interleukin

IL-1β production. Different genotypes lead to distinct phenotypes. One

of the most common mutations, including among the Turkish population,

is the 2080A-G transition in the pyrin gene, resulting in a

met694-to-val (M694V) substitution.[17] In adults, a

high frequency of carriers of the MEFV gene in patients with

hematological neoplasms has been reported, none of whom had a diagnosis

of Hodgkin lymphoma. However, it remains unclear how inherited variants

in the MEFV gene are associated with tumor susceptibility or promotion

in hematologic neoplasms.[10]

Management of FMF with colchicine has benefitted patients by reducing painful attacks and preventing amyloidosis.[18]

Therefore, this drug was continued during initiation of anti-cancer

treatment. However, our patient did not tolerate the combination with

the low-intensity chemotherapy regimen.

Colchicine has a narrow

therapeutic index. It is readily absorbed after oral administration,

but has a variable bioavailability (ranging from 25% to 88%) and

undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism. It has a wide volume of

distribution (Vd) and binds to intracellular elements. Colchicine is

primarily metabolized by the liver, undergoes significant enterohepatic

re-circulation, and is also excreted by the kidneys. CYP3A4 and

P-glycoprotein inhibitors can increase serum colchicine concentrations.

Etoposide, prednisone, vincristine and doxorubicin are substrates of

CYP3A4, and therefore the clearance of these drugs may decrease with

concurrent administration of colchicine, and their side effects may

increase. Since colchicine is also a substrate of CYP3A4, its clearance

may be decreased by these drugs due to competitive inhibition. In

addition, the target for both colchicine and vincristine is tubulin

beta chain which may add to toxicity when administered together.[19]

Thus, our patient may have experienced gastrointestinal adverse effects

and prolonged bone marrow suppression, as described in patients with

colchicine toxicity, due to CYP3A4-mediated impairment of colchicine or

antineoplastic agent metabolism or an additive effect on tubulin

inhibition.[20]

Colchicine was discontinued in

our patient and the second cycle of chemotherapy was well tolerated,

without fever or abdominal pain. She is currently disease-free 17

months after completing therapy.

In summary, to the best of our

knowledge, we describe the first case of Hodgkin lymphoma in a patient

with familial Mediterranean fever. Colchicine should be given with

caution in patients treated with drugs substrate of CYP3A4 and/ or

effecting on tubulin polymerization, like vincristine. To this end, a

strict collaboration between oncology and rheumatology is warranted

when managing these patients.

.

References

- Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A.

Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin.

2014 Mar-Apr;64(2):83-103. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21219 PMid:24488779

- Lee

JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. Prevalence and prognostic significance of

Epstein-Barr virus infection in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: a

meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2014 Jul;45(5):417-31 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.06.001 PMid:24937173

- Tran

H, Nourse J, Hall S, Green M, Griffiths L, Gandhi MK.

Immunodeficiency-associated lymphomas. Blood Rev. 2008

Sep;22(5):261-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2008.03.009 PMid:18456377

- Straus

SE, Jaffe ES, Puck JM, Dale JK, Elkon KB, Rösen-Wolff A, et al. The

development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune

lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective

lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood. 2001 Jul 1;98(1):194-200 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V98.1.194 PMid:11418480

- Goldfinger SE. Colchicine for familial Mediterranean fever. N Engl J Med. 1972. Dec 21;287(25):1302.

- Alghamdi M. Familial Mediterranean fever, review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Aug;36(8):1707-1713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3715-5 PMid:28624931

- Soriano

A, Verecchia E, Afeltra A, Landolfi R, Manna R. (2013) IL-1ß biological

treatment of familial Mediterranean fever. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol.

2013 Aug;45(1):117-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8358-y PMid:23322405

- Celik

S, Tangi F, Oktenli C. Increased frequency of Mediterranean fever gene

variants in multiple myeloma. Oncol Lett. 2014 Oct;8(4):1735-1738. Epub

2014 Aug 4. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2407 PMid:25202401 PMCid:PMC4156200

- Sayan

O, Kilicaslan E, Celik S, Tangi F, Erikci AA, Ipcioglu O, et al. High

Frequency of Inherited Variants in the MEFV Gene in Acute Lymphocytic

Leukemia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2011 Sep;27(3):164-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-011-0095-x PMid:22942567 PMCid:PMC3155719

- Oktenli

C, Celik S. High frequency of inherited variants in the MEFV gene in

patients with hematologic neoplasms: a genetic susceptibility? Int J

Hematol. 2012 Apr;95(4):380-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-012-1061-6 PMid:22453916

- Celik

S, Oktenli C, Kilicaslan E, Tangi F, Sayan O, Ozari HO, et al.

Frequency of inherited variants in the MEFV gene in myelodysplastic

syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2012

Mar;95(3):285-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-012-1022-0 PMid:22351163

- Celik

S, Erikci AA, Tunca Y, Sayan O, Terekeci HM, Umur EE, et al. The rate

of MEFV gene mutations in hematolymphoid neoplasms. Int J Immunogenet.

2010 Oct;37(5):387-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-313X.2010.00938.x PMid:20518828

- Dorffel

W, Luders H, Ruhl U: Preliminary results of the multicenter trial

GPOH-HD 95 for the treatment of Hodgkin's disease in children and

adolescents: Analysis and outlook. Klin Padiatr 215:139-145, 2003 https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-39372 PMid:12838937

- Livneh

A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Zaks N, Kees S, Lidar T, et al. Criteria for

the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1997

Oct;40(10):1879-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780401023 PMid:9336425

- Yalçinkaya

F, Ozen S, Ozçakar ZB, Aktay N, Cakar N, Düzova A, et al. A new set of

criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever in

childhood. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Apr;48(4):395-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken509 PMid:19193696

- Masters

SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the

molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease (*). Annu Rev

Immunol. 2009; 27:621-68. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627 PMid:19302049 PMCid:PMC2996236

- Yilmaz,

E., Ozen, S., Balci, B., Duzova, A., Topaloglu, R., Besbas, et al.

Mutation frequency of familial Mediterranean fever and evidence for a

high carrier rate in the Turkish population. Europ. J. Hum. Genet. 9:

553-555, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200674 PMid:11464248

- Zemer

D, Pras M, Sohar E, Modan M, Cabili S, Gafni J. Colchicine in the

prevention and treatment of the amyloidosis of familial Mediterranean

fever. N Engl J Med. 1986 Apr 17;314(16):1001-5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198604173141601 PMid:3515182

- Lu

Y, Chen J, Xiao M, Li W, Miller DD. An overview of tubulin inhibitors

that interact with the colchicine binding site. Pharm Res. 2012

Nov;29(11):2943-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-012-0828-z PMid:22814904 PMCid:PMC3667160

- Finkelstein

Y, Aks SE, Hutson JR, Juurlink DN, Nguyen P, Dubnov-Raz G, et al.

Colchicine poisoning: the dark side of an ancient drug. Clin Toxicol

(Phila). 2010 Jun;48(5):407-14. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2010.495348 PMid:20586571

[TOP]