Rita Wilson Dib, Ray Hachem, Anne-Marie Chaftari* and Issam Raad.

The University of Texas

M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Infectious Diseases,

Infection Control and Employee Health, 1515 Holcombe, Unite 1460,

Houston, Texas, 77030.

Corresponding

author: Dr. Anne-Marie Chaftari, Department of Infectious

Diseases, Infection Control and Employee Health, Unit 1460, The

University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd.,

Houston, TX 77030. Tel: (713) 792-3491; Fax: (713) 742-7943. E-mail:

achaftar@mdanderson.org

Published: May 1, 2018

Received: , 2018

Accepted: , 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018028 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.028

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

In

this review, we have analyzed the available literature pertaining to

the total duration of intravenous (IV) therapy and the appropriate

timing of step down to oral therapy in the management of candidemia.

Overview of the guidelines and literature seem to indicate that a

minimum of 14 days of antifungal therapy is required in the treatment

of candidemia without deeply seated infection. However, this was never

based on evidence. Furthermore, step down to oral therapy seems to be

dependent on the clinical stability criteria of the patient with

candidemia after 4 to 7 days of IV therapy. Further studies are

required to evaluate the appropriate total duration of IV therapy,

appropriate timing of step down to oral therapy and to validate the

clinical criteria that would allow the switch to happen.

|

Introduction

Candidemia

is the most common form of invasive candidiasis and one of the leading

causes of bloodstream infections (BSI) in critically ill and

immunosuppressed patients.[1,2] It is widely recognized for its high morbidity and mortality rates ranging between 10 to 47%.[3,4]

Furthermore, candidemia has an added severity in immunosuppressed and

critically ill patients. Given the high risk it poses, appropriate

treatment and eradication of the organism remain crucial.

The

most recent guidelines for the management of Candidemia without deeply

seated complications (published by the Infectious Diseases Society of

America (IDSA) in 2016) recommended a minimum of 14 days of antifungal

therapy after documented blood culture clearance in a clinically stable

state.[5] In the case of neutropenia, the guidelines also entail recovery of the white cell count.[5]

However, these recommendations are based on limited clinical evidence

grounded on the results of a number of trials in which this practice

has been implied and routinely applied both in the non-neutropenic and

less often the neutropenic population.[6-9]

In a

milestone study by Rex et al. published in the New England Journal of

Medicine in 1994 showing the equivalence of fluconazole to amphotericin

B in the treatment of candidemia, the duration of therapy in both arms

was mandated to be 2 weeks after the last negative blood culture.[7]

Unfortunately, this practice has been carried through routinely as norm

through the literature and guidelines over the last three decades in

the absence of other studies to compare the impact of total duration of

therapy and appropriate time to step down to oral therapy.

Duration of Therapy

Early initiation of antifungal agents in this population has been associated with favorable survival outcome[10]

but the question remains as to when it should be stopped. To our

knowledge, there were no randomized studies in the literature comparing

different duration of treatment and a limited number looked at the

appropriate timing of the step down from intravenous (IV) to oral

antifungal therapy.

Hence, it is necessary to evaluate the

available data on the total duration of therapy of uncomplicated

candidemia given the importance of the subject matter.

One would

argue that a long duration of therapy is useful for prevention or

unintentional treatment of undiscovered foci of infection given the

fact that up to 16% of candidemic patients have some exhibition of

ocular involvement, with devastating consequences in inappropriately

treated patients.[11] In a study by Blennow et al.,

two to three weeks of antifungal treatment was found to be adequate to

treat undetected ocular infections in the setting of candidemia without

signs of metastatic infection at onset. In this cohort, 21 patients

received <=14 days of therapy. Among them, only one patient

developed proven endophthalmitis after having received only 2 days

(total) of therapy.[12] However, we cannot draw

conclusions from this study on the effect of duration of therapy since

the patients could be treated longer as a consequence to having a

possible or probable ocular candidiasis. In addition, the authors did

not distinguish the duration of IV versus oral therapy.

Step Down to Oral Therapy

A

suggested strategy to keep the balance between the need for aggressive

therapy and not overdoing it, is to do step down to oral therapy. It

was recommended by the IDSA to step down within 5 to 7 days once the

patient achieves symptom resolution and clearance of the blood cultures

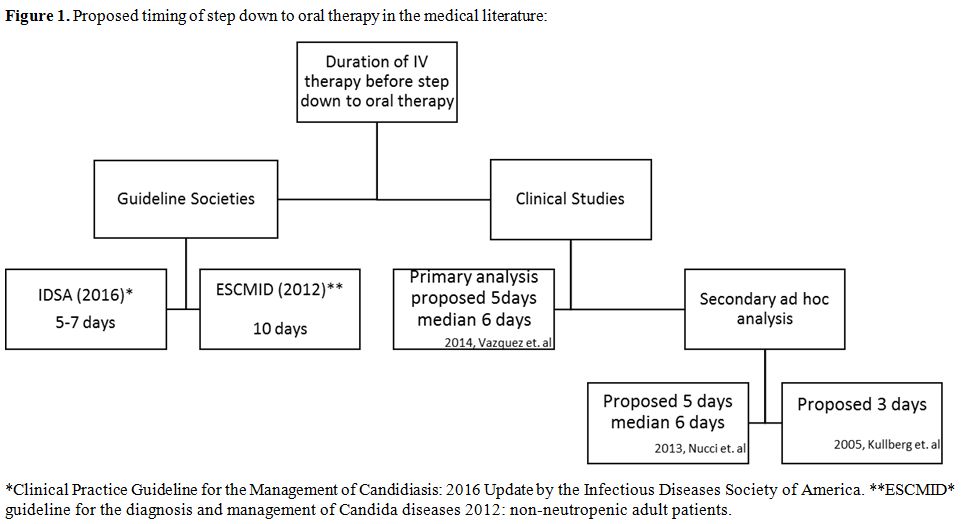

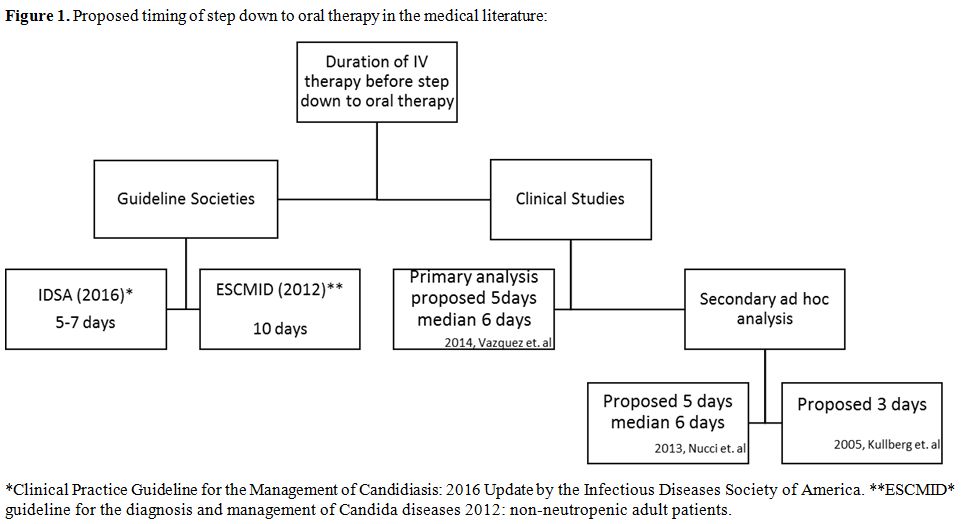

(Figure 1).[5]

In 2012, the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious

Diseases (ESCMID) proposed stepping down to oral fluconazole after 10

days of therapy if the patient was stable and the isolated candida

species demonstrate appropriate minimal inhibitory concentrations

(MICs) to the drug.[13]

|

Figure 1. Proposed timing of step down to oral therapy in the medical literature |

In

the actual practice, physicians are applying the step down therapy as

per their clinical judgment. Setting clinical stability is not

uniformly defined. Some studies relied on the hemodynamic status and

microbiologic eradication, while others relied on the improvement in

clinical signs and symptoms (defervescence for 24 hours) along with

microbiological eradication.[14,15]

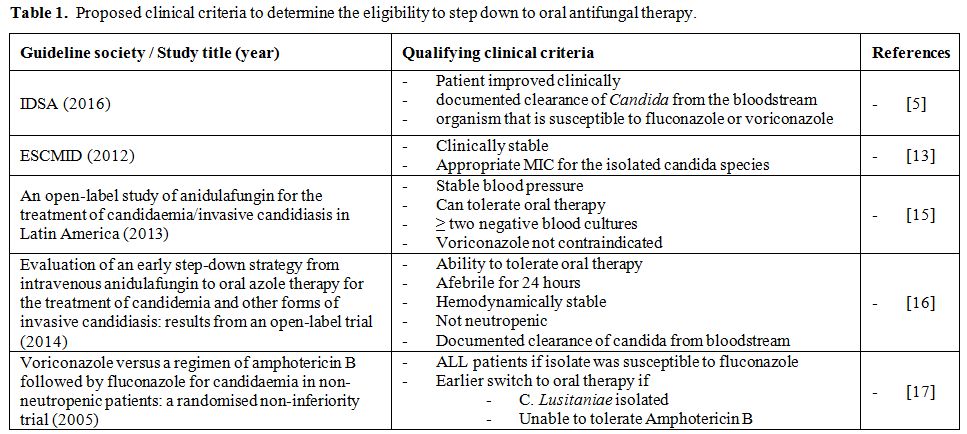

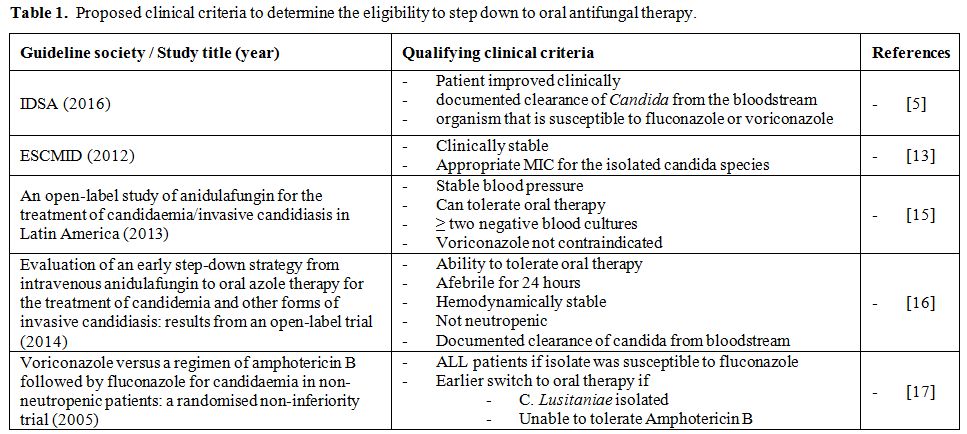

A trial

conducted in several centers in Latin America, patients were eligible

for step down after at least 5 days of anidulafungin if they had

“stable blood pressure “ and at least two negative blood cultures. Only

14 out of 44 qualified for step down to voriconazole with a median

duration of IV therapy of six days. They were all found to have lower

APACHE II score and lower incidence of solid tumors compared with

others making them less sick. Global response and overall mortality

were significantly lower in the step down group.[15]

Even though the number of enrolled patients is small, this study showed

the feasibility of the step down therapy but it did not give us an idea

on the efficacy of stepping down the therapy to oral formulation in

high risk patients especially that the two approved/used agents

(fluconazole and voriconazole) show >90% oral bioavailability.

An

open-label non-comparative trial evaluated global response rates,

defined by clinical improvement and microbiological eradication, of

patients with candidemia who were treated with anidulafungin followed

by oral fluconazole (if baseline cultures revealed C. albicans or C. parapsilosis)

or voriconazole (all other species) after a minimum of 5 days of

anidulafungin provided that the patients were clinically stable.[16]

The step down criteria consisted of 24 hours off fever, hemodynamic

stability and documentation of sterile blood cultures and resolved

neutropenia. A total of 150 patients underwent a step down to oral

therapy, 56% of them qualified for the switch to oral therapy within 6

days with a median of 5 days [range, 1-6]. On the other hand, 44% did

not meet the criteria within the first 6 days of therapy and the median

duration of their IV therapy was 10 days [range, 7-27]. The overall

response in the group of patients who underwent early step down versus

the modified intention to treat (MITT) population did not differ.[16]

Again it was noted that the patients who were switched to oral therapy

before 7 days from onset had lower APACHE scores. This study shows that

early step down to oral therapy within 6 days is dependent on certain

clinical stability criteria (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Proposed clinical criteria to determine the eligibility to step down to oral antifungal therapy. |

Another

study compared voriconazole to amphotericin B therapy whereby the

protocol allowed switch from IV voriconazole to oral voriconazole and

from IV amphotericin to oral fluconazole. The median duration of

amphotericin B was 4 days.[17] Even though the

authors did not mention the median duration of IV voriconazole therapy

and the percentage of patients switched to the oral formulation, there

was no significant difference in overall response between the two

groups.

Another concern with the current proposed step down

strategies was raised by Glockner et.al which is the vague definition

of the timing of documented negative blood culture. This timing

may vary depending on how often the blood cultures are taken and the

fact that they are known to have slow turnaround times with median time

to positivity of 2–3 days reaching 7 days in some situations.[18,19]

Glockner at al., therefore, suggest to consider the timing of

collection of the first negative blood culture as a starting point to

initiate step down strategies.

What is notable in many of the

conducted studies is that microbiologic eradication ranged between 2

and 5 days regardless of the antimicrobial agent and the route of

administration.[16,17,20] This finding could be used to set an appropriate time to consider stepping down or de-escalating the treatment safely.

No

studies showed superiority of any agent, however, both the ESCMID and

the IDSA guidelines suggest the initiation of echinocandins with a

later step down to an appropriate agent based on the susceptibility

pattern and the patient’s clinical status.[5,13]

The reason that these agents have become the common practice is their

fungicidal activity whereby susceptibility studies have shown low MIC

for Candida species including C. glabrata and C. krusei.[21,22] Furthermore, echinocandins demonstrated a survival advantage in non-neutropenic patients.[23]

In addition, they are only available in intravascular formulation which

puts the patients in situations where they have to stay as inpatients

to receive their treatment or face the hurdles of home IV therapies. In

addition, they reportedly have minimal adverse effects with limited

drug interactions.[24]

However, recent case series have described treatment failure associated with growing resistance among strains comprising C. glabrata and C. tropicalis.[25,26]

Hence,

it is important to establish the feasibility of a step down therapy

from echinocandins especially to address the aforementioned increasing

risk of resistance. On the other hand, stepping down from IV therapy

when feasible might also positively affect the healthcare cost in this

subset of patients while maintaining the successful clinical outcome as

shown in previous des-escalation cost effective analysis from studies

from the UK and China.[27,28] Conclusions

In

conclusion, the current practice in the management and treatment of

candidemia and invasive candidiasis is based on inference rather than

evidence. This incites the need for more comprehensive studies

comparing the different management strategies and their outcomes. Such

strategies should ideally account for specific risk factors and

comorbidities which will help identify candidates for early step down.

However, based on the available data and the occurrence of clinical

response, step down to oral therapy between days 4-7 after initiation

of IV therapy seems to be reasonable in most cases. Additional studies

are needed to further validate and define the clinical criteria that

would allow early step down to oral therapy.

References

- Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto

A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes

of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2323-9. PubMed

PMID: 19952319. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1754

- Martin

GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the

United States from 1979 through 2000. New Engl J Med.

2003;348(16):1546-54. PubMed PMID: WOS:000182248900005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa02213

- Gudlaugsson

O, Gillespie S, Lee K, Vande Berg J, Hu J, Messer S, et al.

Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin Infect

Dis. 2003;37(9):1172-7. PubMed PMID: 14557960. https://doi.org/10.1086/378745

- Pappas

PG, Rex JH, Lee J, Hamill RJ, Larsen RA, Powderly W, et al. A

prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy,

and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and pediatric

patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(5):634-43. PubMed PMID: 12942393. https://doi.org/10.1086/376906

- Pappas

PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et

al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016

Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis.

2016;62(4):e1-50. PubMed PMID: 26679628; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMCPMC4725385. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ933

- Kuse

ER, Chetchotisakd P, da Cunha CA, Ruhnke M, Barrios C, Raghunadharao D,

et al. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and

invasive candidosis: a phase III randomised double-blind trial. Lancet.

2007;369(9572):1519-27. PubMed PMID: 17482982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60605-9

- Rex

JH, Bennett JE, Sugar AM, Pappas PG, Vanderhorst CM, Edwards JE, et al.

A Randomized Trial Comparing Fluconazole with Amphotericin-B for the

Treatment of Candidemia in Patients without Neutropenia. New Engl J

Med. 1994;331(20):1325-30. doi: PubMed PMID: WOS:A1994PR21600001.

- Pappas

PG, Rotstein CM, Betts RF, Nucci M, Talwar D, De Waele JJ, et al.

Micafungin versus caspofungin for treatment of candidemia and other

forms of invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):883-93.

PubMed PMID: 17806055. https://doi.org/10.1086/520980

- Betts

RF, Nucci M, Talwar D, Gareca M, Queiroz-Telles F, Bedimo RJ, et al. A

Multicenter, double-blind trial of a high-dose caspofungin treatment

regimen versus a standard caspofungin treatment regimen for adult

patients with invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis.

2009;48(12):1676-84. PubMed PMID: 19419331. https://doi.org/10.1086/598933

- Morrell

M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the empiric treatment of Candida

bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are

obtained: a potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob

Agents Ch. 2005;49(9):3640-5. PubMed PMID: WOS: 000231542900006. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.49.9.3640-3645.2005

- Oude

Lashof AM, Rothova A, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M, Pappas PG, Viscoli C, et al.

Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):262-8.

PubMed PMID: 21765074. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir355

- Blennow

O, Tallstedt L, Hedquist B, Gardlund B. Duration of treatment for

candidemia and risk for late-onset ocular candidiasis. Infection.

2013;41(1):129-34. PubMed PMID: 23212461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-012-0369-8

- Cornely

OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, et

al. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida

diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect.

2012;18 Suppl 7:19-37. PubMed PMID: 23137135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12039

- Reboli

AC, Rotstein C, Pappas PG, Chapman SW, Kett DH, Kumar D, et al.

Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J

Med. 2007;356(24):2472-82. PubMed PMID: 17568028. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa066906

- Nucci

M, Colombo AL, Petti M, Magana M, Abreu P, Schlamm HT, et al. An

open-label study of anidulafungin for the treatment of

candidaemia/invasive candidiasis in Latin America. Mycoses.

2014;57(1):12-8. PubMed PMID: 23710653. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12094

- Vazquez

J, Reboli AC, Pappas PG, Patterson TF, Reinhardt J, Chin-Hong P, et al.

Evaluation of an early step-down strategy from intravenous

anidulafungin to oral azole therapy for the treatment of candidemia and

other forms of invasive candidiasis: results from an open-label trial.

BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:97. PubMed PMID: 24559321; PubMed Central

PMCID: PMCPMC3944438. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-97

- Kullberg

BJ, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M, Pappas PG, Viscoli C, Rex JH, et al.

Voriconazole versus a regimen of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole

for candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients: a randomised

non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9495):1435-42. PubMed PMID:

16243088. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67490-9

- Glockner

A, Cornely OA. Practical considerations on current guidelines for the

management of non-neutropenic adult patients with candidaemia. Mycoses.

2013;56(1):11-20. PubMed PMID: 22574925. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02208.x

- Zaoutis

TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C. The epidemiology

and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children

hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin Infect

Dis. 2005;41(9):1232-9. PubMed PMID: 16206095. https://doi.org/10.1086/496922

- Reboli

AC, Shorr AF, Rotstein C, Pappas PG, Kett DH, Schlamm HT, et al.

Anidulafungin compared with fluconazole for treatment of candidemia and

other forms of invasive candidiasis caused by Candida albicans: a

multivariate analysis of factors associated with improved outcome. BMC

Infect Dis. 2011;11:261. PubMed PMID: 21961941; PubMed Central PMCID:

PMCPMC3203347. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-261

- Pfaller

MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Kroeger J, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, et al. In

vitro susceptibility of invasive isolates of Candida spp. to

anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin: six years of global

surveillance. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(1):150-6. PubMed PMID:

18032613; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2224271. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01901-07

- Pfaller

MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Kroeger J, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, et al.

Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the

echinocandins and Candida spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):52-6.

PubMed PMID: 19923478; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2812271. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01590-09

- Mora-Duarte

J, Betts R, Rotstein C, Colombo AL, Thompson-Moya L, Smietana J, et al.

Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis.

N Engl J Med. 2002;347(25):2020-9. PubMed PMID: 12490683. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021585

- Bassetti

M, Righi E, Montravers P, Cornely OA. What has changed in the treatment

of invasive candidiasis? A look at the past 10 years and ahead. J

Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(suppl_1):i14-i25. PubMed PMID: 29304208. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx445

- Kontoyiannis

DP, Vaziri I, Hanna HA, Boktour M, Thornby J, Hachem R, et al. Risk

Factors for Candida tropicalis fungemia in patients with cancer. Clin

Infect Dis. 2001;33(10):1676-81. PubMed PMID: 11568858. https://doi.org/10.1086/323812

- Farmakiotis

D, Tarrand JJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Drug-resistant Candida glabrata

infection in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(11):1833-40.

PubMed PMID: 25340258; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4214312. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2011.140685

- Masterton

RG, Casamayor M, Musingarimi P, van Engen A, Zinck R, Odufowora-Sita O,

et al. De-escalation from micafungin is a cost-effective alternative to

traditional escalation from fluconazole in the treatment of patients

with systemic Candida infections. J Med Econ. 2013;16(11):1344-56.

PubMed PMID: 24003830. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2013.839948

- Chen

D, Wan X, Kruger E, Chen C, Yue X, Wang L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of

de-escalation from micafungin versus escalation from fluconazole for

invasive candidiasis in China. J Med Econ. 2018;21(3):301-7. PubMed

PMID: 29303621. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2017.1417312

[TOP]