Nicolò Peccatori1, Roberta Ortiz2, Emanuela Rossi3, Patricia Calderon2, Valentino Conter1, Yesly García2, Andrea Biondi1, Darrel Espinoza2, Francesco Ceppi4, Luvy Mendieta5 and Maria Luisa Melzi1.

1 Centro di Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica Maria Letizia Verga, S. Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy.

2 Department of Hematology/Oncology, Children’s Hospital Manuel de Jesus Rivera, Managua, Nicaragua.

3

Center of Biostatistics for Clinical Epidemiology, Department of

Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy.

4

Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Unit Pediatric Hematology-Oncology

Research Laboratory, Division of Pediatrics, Department of

Woman-Mother-Child, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne,

Switzerland.

5 Department of Nutrition, Children’s Hospital Manuel de Jesus Rivera, Managua, Nicaragua.

Corresponding

author: Valentino Conter, Centro di Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica Maria

Letizia Verga, S. Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca. Via

Pergolesi 33, 20900 Monza (MB), Italy. Fax: (011) 39-039-2301646.

E-mail:

valentino.conter@gmail.com

Published: June 23, 2018

Received: October 3, 2018

Accepted: May 24, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018038 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.038

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Children

with cancer are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition, which can

affect their tolerance of chemotherapy and outcome. In Nicaragua

approximately two-thirds of children diagnosed with cancer present with

under-nutrition. A nutritional program for children with cancer has

been developed at “La Mascota” Hospital. Results of this oral

nutritional intervention including difficulties, benefits, and

relevance for children treated for cancer in low- and middle-income

countries are here reported and discussed.

|

Introduction

The

pediatric population diagnosed with cancer is at high risk of

malnutrition for cancer and treatment related effects. Children with

cancer tend to become malnourished during treatment because of multiple

reasons. Pain, anorexia, hormonal and inflammatory components, low

physical activity, taste aversions and chronic medications are all

factors which lead to decreased oral calories intake and can contribute

to malnutrition.[1,2] Malnutrition can affect the

tolerance of both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, may increase the risk

of comorbidities and influence overall survival.[3]

Approximately

80% of children and adolescents who are diagnosed with cancer live in

low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to quality care

and chances of cure are limited. In LMICs, malnutrition represents one

of the major obstacles to effective pediatric care, together with late

diagnosis, abandonment of therapy, suboptimal supportive care, and

inefficient health-care delivery systems.[4]

In LMICs it is estimated that the prevalence of malnutrition averages 50% in children with cancer.[5]

In Nicaragua, the prevalence of malnutrition in children under 5 years

of age according to UNICEF is 30%, with 23% of children presenting

severe malnutrition and 7% moderate malnutrition.[6] A study performed in the hemato-oncology centers of the AHOPCA (Asociación de Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica Centro-Americana)[7]

countries, between 2004 and 2007, showed that nutritional status of

children with cancer at diagnosis was normal in 37% of patients,

moderately depleted in 18% and severely depleted in 45%.[8]

In Nicaragua at the Children’s Hospital Manuel de Jesus Rivera “La

Mascota” (HIMJR), 67% of patients were classified as malnourished at

diagnosis, including 47.9% with severe malnutrition.[9]

On

the basis of these evidences, a nutritional program for children

diagnosed with cancer who were inadequately nourished was developed at

HIMJR, in collaboration with the Pediatric Hemato-Oncology Center of

Monza (Milano-Bicocca University), in the context of the Monza

International School of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (MISPHO)

initiative.[10]

HIMJR is the only hospital of

Nicaragua where children with cancer can be treated; approximately 250

children with cancer per year are referred from the whole country.

The

nutritional program started in February 2016 with the objectives to

reduce the adverse effect of malnutrition on treatment related

morbidity and improve clinical outcome.

The aim of this study is

to assess the role of oral/enteral supplementation in children treated

for oncological diseases in the context of LMICs, where this

intervention still needs to be properly investigated.

Material and Methods

Patients

with cancer, aged one month to 17 years, diagnosed between February

2016 and March 2017 at the HIMJR were screened for nutritional status

by a qualified nutritionist at diagnosis. The nutritional status

assessment was based on weight, height or length and the anthropometric

measures of mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and triceps skin fold

thickness (TSFT), as already reported.[8]

TSFT and MUAC percentiles were estimated for age and gender using the LMS procedure according to the CDC and WHO growth charts.[11] Patients were considered adequately nourished (AN) if both TSFT and MUAC were >10th percentile, severely depleted (SD) if TSFT or MUAC <5th percentile, and moderately depleted (MD) in all other cases.

Eligible

for the study, after obtaining written informed consent from parents or

legal guardians, were: 1) patients inadequately nourished at diagnosis,

2) patients with borderline nutritional status at diagnosis undergoing

intensive chemotherapy, considered at high risk of developing

under-nutrition by the nutritionist and treating physician, and 3)

patients developing under-nutrition during the treatment. Children with

advanced disease at diagnosis and eligible only for palliative care

were excluded.

Patients entered in the study were given oral

polymeric hyper-caloric formulas containing a balanced mixture of

proteins, fats, and carbohydrates according to the indication by age

for patients up to 10 years or older (up to 17 years). Parents were

instructed to reconstitute formulas with water and to administer them

to their children at home after discharge from the hospital. The

adherence to the nutritional treatment was ascertained by the

nutritionist from parents’ interviews.

Only when oral feeding

was not considered possible or safe, formulas were administered through

enteral feeding. Nutritionists and treating physicians decided the

schedule of nutritional reassessments on the basis of the clinical

conditions and the treatment plan for each patient.

Gender, date

of birth, date of diagnosis, dates of nutritional assessment and type

of cancer were recorded. The data were collected in the

Pediatric-Oncology-Network-Database (POND).[12]

This

study has made a comparison with a historical cohort of patients with

comparable characteristics diagnosed from 2004 to 2007 at HIMJR,[8]

to evaluate the impact on event-free-survival (EFS) of the addition of

nutritional support. Their nutritional status has been here

re-classified according to the schema adopted in the current study.

Statistical analysis.

Patients’ characteristics were described using frequency, percentages,

medians and interquartile range (IQR). The 1-year EFS was estimated in

the overall cohort of 104 patients, and a comparison between the cohort

in the study and the historical one was made using Kaplan Meier

survival curves and tested using Andersen pseudo-values regression,

adjusting for type of tumor and nutritional status at first evaluation.

This test was adopted due to the extremely different follow-up duration

of the two cohorts.

P-values were considered statistically

significant if lower than 0.05. Statistical analyses and figure were

done with SAS v9.4, STATA and R.

Results

A

total of 259 children were diagnosed with cancer at HIMJR in the period

of the study; of them, 104 entered the study and received nutritional

supplementation. Nutritional formulas were given free of charge and

were accepted by all families.

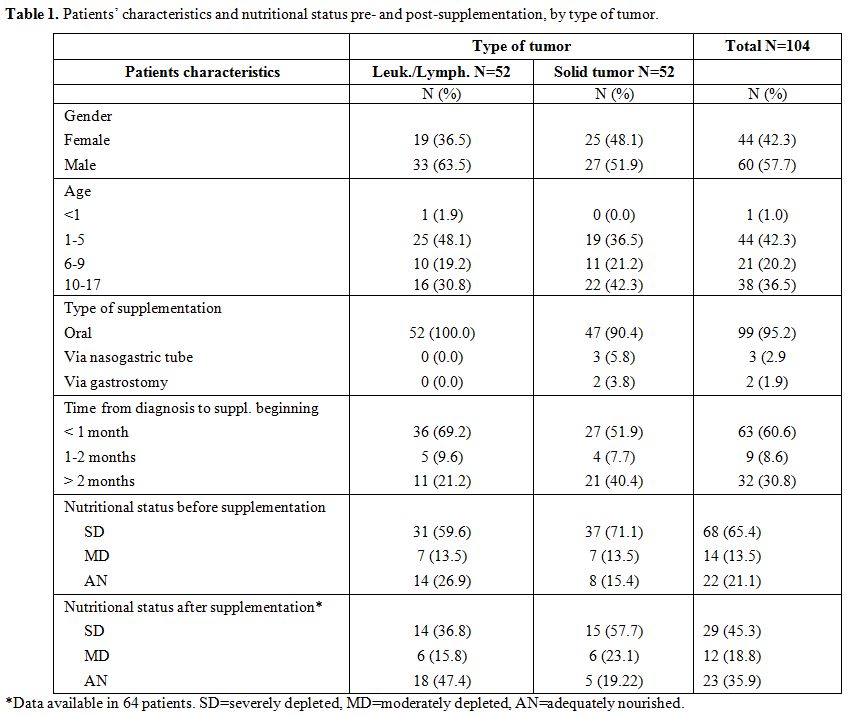

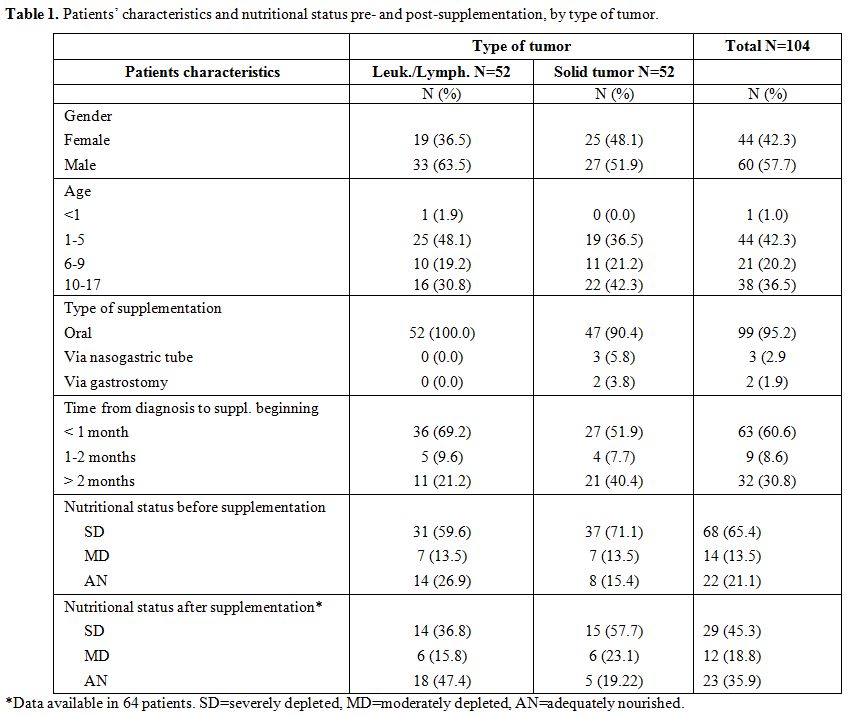

Patients’ characteristics at the onset of disease are described in table 1.

Forty-four were female (42.3%), and 60 were male (57.7%); 34 were

affected by acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 5 by acute myeloid

leukemia, 13 by lymphomas and 52 by solid tumors, including brain

tumors (n=20), retinoblastoma (n=3), bone and soft-tissue sarcoma

(n=15), Wilms’ tumor (n=7) and others (n=7). Diseases were clustered in

two groups -leukemia/lymphomas and solid tumors- for further analyses.

At

the start of the nutritional support, the median age was 7.0 years

(IQR: 3.4-11.5). Almost all patients (n=99) were exclusively orally

supplemented; in only three patients the nutritional formula was

administered via nasogastric tube and in two via gastrostomy. The

nutritional supplementation was started within one month from diagnosis

in 63 cases (60.6%), between 1 and 2 months in 9 patients (8.6%) and

later than 2 months in 32 cases (30.8%). At first work-up (before

supplementation) according to their anthropometric measurements

patients were overall classified as follows: 65.4% severely depleted,

13.5% moderately depleted and 21.1% borderline/adequately nourished

(considered at risk of developing under-nutrition during treatment) (Table 1).

Seventeen

patients died of progressive disease, and 23 did not have a nutritional

follow-up. Thus, nutritional reassessment after supplementation was

performed in 64 patients at a median time from the first assessment of

2.7 months (IQR 2.0-5.4); 29 of them were severely depleted (45.3%), 12

moderately depleted (18.8%) and 23 adequately nourished (35.9%) (Table 1).

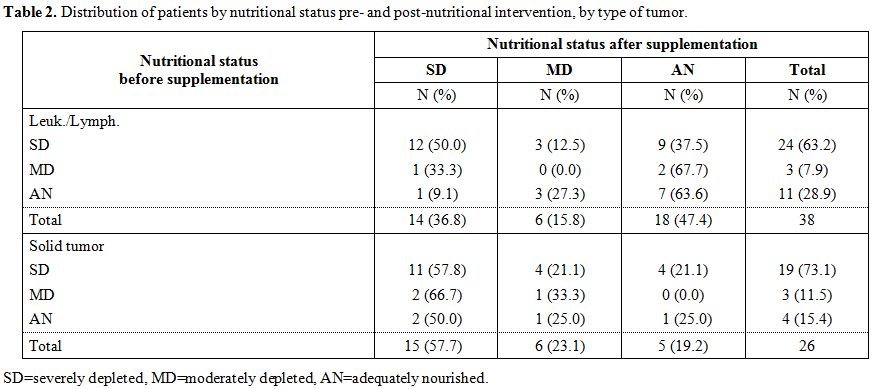

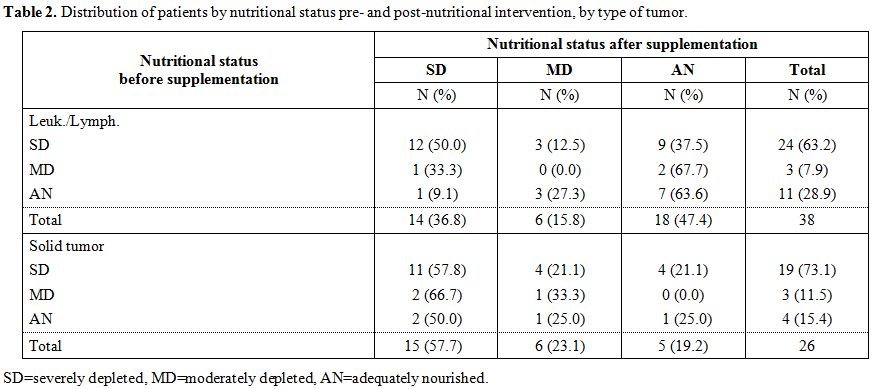

Compared with the first evaluation there was a decrease in the

percentage of severely depleted patients in both leukemia/lymphoma

groups (from 63.2 to 36.8%) and the solid tumor group (from 73.1 to

57.7%). Furthermore, in leukemia/lymphoma group, we observed an

increase in the percentage of adequately nourished patients from 28.9%

to 47.4% (Table 2)

|

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and nutritional status pre- and post-supplementation, by type of tumor. |

|

Table 2. Distribution of patients by nutritional status pre- and post-nutritional intervention, by type of tumor. |

Overall, 55% of

patients in leukemia/lymphoma group and 35% in the solid tumor group

improved their condition or remained in an adequately nourished status.

There was not a significant statistical difference between the

proportions of patients improved by type of tumor (p-value=0.104).

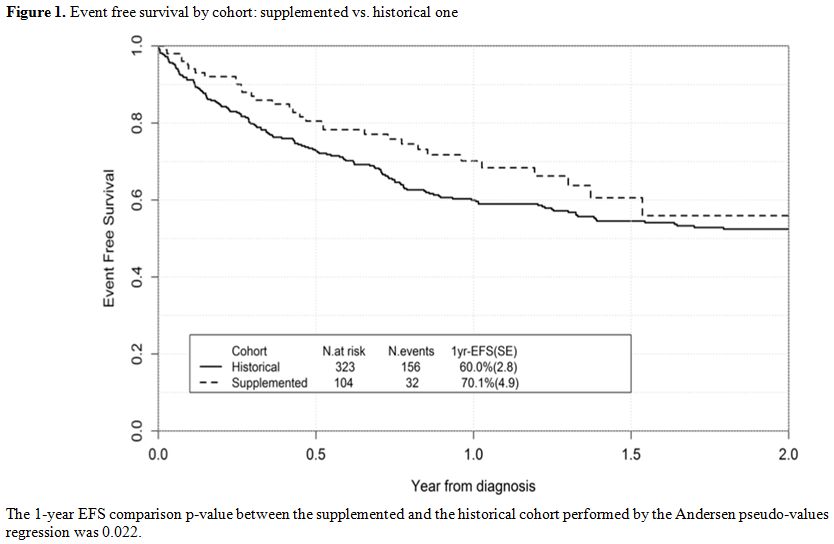

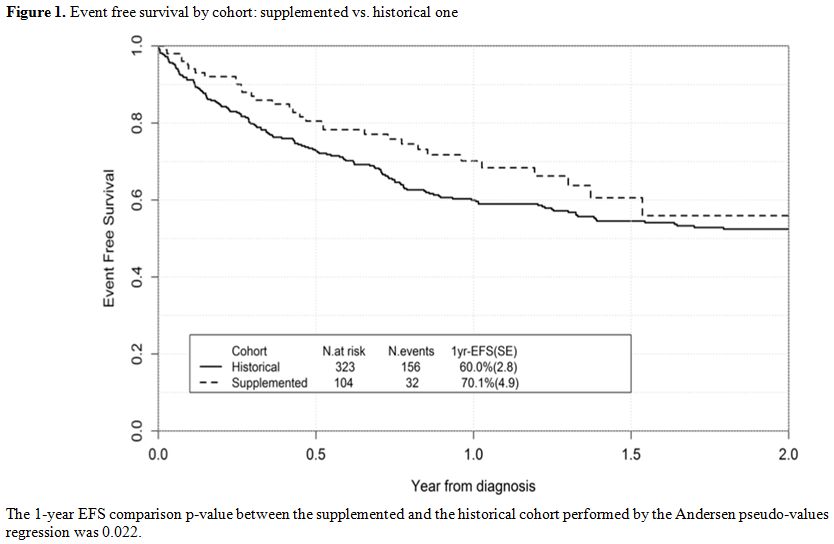

The

1-year EFS of the overall cohort of patients recruited in this study

was 70.1%, which compares favorably with that of a historical cohort of

patients treated at HIMJR and not supplemented, who had a 1-year EFS of

60% (SE=2.8), p-value=0.022 (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Event free survival by cohort: supplemented vs. historical one |

Adjusting

for the type of tumor and nutritional status at diagnosis the

supplemented cohort seemed to have statistically significant 1-year EFS

higher than the historical cohort (p-value=0.013, gain in EFS of about

13%, 95% CI=[2.9%-24.0%]).

Discussion

Malnutrition

remains a critical health issue for pediatric oncology in LMICs, where

the nutritional status of children with cancer has an important effect

on the outcome, being associated with the risk of abandonment and low

tolerance of therapy.[8,9,13] Thus,

children with oncological diseases should be regularly assessed for

nutritional status and supported, as recommended by the SIOP PODC

(Nutrition Working Group of the Society of Pediatric Oncology), that

presented a framework for establishing and monitoring nutritional care,

based on the infrastructure of institutions in LMICs.[14]

A

recent study performed in Guatemala in childhood ALL showed that

establishing an appropriate nutritional program may overcome the

adverse prognostic impact of malnutrition.[15] Data on effects of oral/enteral nutritional support programs in pediatric cancer patients are, however, quite limited.[16]

Thus, there is still a need for further investigations to assess

feasibility, costs and efficacy of nutritional interventions in

children with cancer treated in LIMICs.

Our experience

demonstrates that oral supplementation with polymeric formulas has a

favorable impact on the nutritional status in a relevant number of

cases. Overall, in this study after the supplementation, 55% of

patients in leukemia/lymphoma group and 35% in the solid tumor group

improved their condition or remained in an adequately nourished status

despite the toxicity of treatment. This intervention also appears to

have contributed to improving the 1-year EFS as also reported in the

Guatemala experience.[15]

However, since a

significant fraction of patients with severe malnutrition (23/43) did

not improve their nutritional status, it may be inferred that a more

intensive nutritional support with enteral feeding could have been more

beneficial for these patients. In this study enteral-tube-feeding (ETF)

was administered only in very few cases (5/104), due to fear of

complications, particularly in patients with neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia, and mucositis. These reasons may have played a role

in inducing reluctance in both physicians and families to use ETF. The

use of ETF may however be feasible also in these circumstances as

suggested by a study published in 2001, which showed that tube feeding

was safe and cost-effective in children treated with intensive

chemotherapy.[17] Data in this field remain however extremely limited.[18]

The risk-benefit of the use of ETF should thus be carefully

investigated, in order to define the most appropriate strategies of

nutritional support in these patients, particularly in LMICs where the

need of enteral nutrition but also the risk of complications may be

higher compared to high-income countries.

Another aspect of

interest regards the use of commercial formulas. In our experience,

these formulas, which are expensive and not easily available in LMICs,

were often not well accepted by the patients and their parents, who

would have instead favored homemade preparations. It should thus be

considered the appropriateness of homemade oral supplements as a viable

alternative, as described by a study conducted in Brazil.[19]

Although

the weaknesses related to the small number of patients, the shortage of

personnel, the lack of standardization between first and second

nutritional evaluation and the heterogeneity of disease population,

this study in our opinion provides important information. Our

experience indicates that oral nutritional support in children treated

for cancer in LMICs may be helpful to improve outcome and that homemade

formulas should be considered according to the local contexts. Large

prospective studies should be conducted to establish the best

cost-effective methodologies in LMICs and the role of enteral nutrition

in the patients not responding to oral supplementation.

Malnutrition in children with cancer should not be tolerated as an inevitable process,[3]

also and above all in LMICs, where nutritional interventions with the

aim to prevent or reverse malnutrition should be part of routine

supportive care in the treatment plan for childhood cancer.

.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank “Chiesa Valdese Italiana” and “Comitato Maria Letizia Verga” for their support.

References

- Schoeman J. Nutritional assessment and intervention in a pediatric oncology unit. Indian J Cancer 2015;52:186-90. http://www.indianjcancer.com/text.asp?2015/52/2/186/175832

- Sala, A., Pencharz, P. and Barr, R. D. Children, cancer, and nutrition—A dynamic triangle in review. Cancer. 2004;100: 677–687. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11833

- Jacqueline

Bauer, Heribert Jürgens, Michael C. Frühwald; Important Aspects of

Nutrition in Children with Cancer, Advances in Nutrition, Volume 2,

Issue 2, 1 March 2011, Pages 67–77. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.110.000141

- Rodriguez-Galindo

C, Friedrich P, Alcasabas P, et al. Toward the Cure of All Children

With Cancer Through Collaborative Efforts: Pediatric Oncology As a

Global Challenge. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(27):3065-3073. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6376

- Barr

RD, Ribeiro RC, Agarwal BR, Masera G, Hesseling PB, Magrath IT.

Pediatric oncology in countries with limited resources. In: Pizzo PA,

Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2002:1541–1552.

- UNICEF. The state of the world’s children 2012. https://www.unicef.org/sowc2012/

- Barr,

R. D., Klussmann, F. A., Baez, F., Bonilla, M., Moreno, B., Navarrete,

M., Nieves, R., Peña, A., Conter, V., De Alarcón, P., Howard, S. C.,

Ribeiro, R. C., Rodriguez-Galindo, C., Valsecchi, M. G., Biondi, A.,

Velez, G., Tognoni, G., Cavalli, F. and Masera, G. Asociación de

Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica de Centro América (AHOPCA): A model for

sustainable development in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

2014;61: 345–354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24802

- Sala

A, Rossi E, Antillon F, et al. Nutritional status at diagnosis is

related to clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with cancer: a

perspective from Central America. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(2):243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.006

- Pribnow

AK, Ortiz R, Báez LF, Mendieta, L, Luna-Fineman S. Effects of

malnutrition on treatment-related morbidity and survival of children

with cancer in Nicaragua. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26590. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26590

- Howard

SC, Marinoni M, Castillo L, et al. Improving outcomes for children with

cancer in low-income countries in Latin America: A report on the recent

meetings of the Monza International School of Pediatric

Hematology/Oncology (MISPHO)—Part I. Pediatr Blood Cancer

2007;48:364–369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21003

- https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/

- Quintana

Y, Patel AN, Arreola M, et al. POND4Kids: A global web-based database

for pediatric hematology and oncology outcome evaluation and

collaboration. Stud Health Technol Inform, 2013;183:251–256.

- Antillon,

F., Rossi, E., Molina, A. L., Sala, A., Pencharz, P., Valsecchi, M. G.

and Barr R.. Nutritional status of children during treatment for acute

lymphoblastic leukemia in Guatemala. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:

911–915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24377

- Ladas,

E. J., Arora, B., Howard, S. C., Rogers, P. C., Mosby, T. T. and Barr,

R. D.. A Framework for Adapted Nutritional Therapy for Children With

Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Report From the SIOP PODC

Nutrition Working Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63: 1339–1348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26016

- Antillón,

F. G., Blanco, J. G., Valverde, P. D., Castellanos, M., Garrido, C. P.,

Girón, V., Letona, T. R., Osorio, E. J., Borrayo, D. A., Mack, R. A.,

Melgar, M. A., Lorenzana, R., Ribeiro, R. C., Metzger, M., Conter, V.,

Rossi, E. and Valsecchi, M. G.. The treatment of childhood acute

lymphoblastic leukemia in Guatemala: Biologic features, treatment

hurdles, and results. Cancer. 2017;123: 436–448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30257

- Ward

EJ, Henry LM, Friend AJ, Wilkins S, Phillips RS. Nutritional support in

children and young people with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD003298. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003298.pub3/abstract

- DeSwarte-Wallace

J, Firouzbakhsh S, Finklestein JZ, Using research to change practice:

enteral feedings for pediatric oncology patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs.

2001 Sep-Oct;18(5):217-23. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpon.2001.26875

- Trimpe

K, Shaw MR, Wilson M, Haberman MR. Review of the effectiveness of

enteral feeding in Pediatric oncology patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs.

2017 Nov/Dec;34(6):439-445.

- Garófolo,

Adriana, Alves, Fernanda Rodrigues, & Rezende, Maria Aurélia do

Carmo. Suplementos orais artesanais desenvolvidos para pacientes com

câncer: análise descritiva. Revista de Nutrição, 2010;23(4), 523-533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1415-52732010000400003

[TOP]