Paola Zanotti1*, Claudia Chirico1*, Maurizio Gulletta1, Laura Ardighieri2, Salvatore Casari3, Eugenia Quiros Roldan1, Ilaria Izzo1, Gabriele Pinsi4, Giovanni Lorenzin4,5, Fabio Facchetti2, Francesco Castelli1 and Emanuele Focà1.

1 Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia and ASST Spedali Civili General Hospital, Brescia, Italy.

2 Pathology Unit, University of Brescia and ASST Spedali Civili General Hospital, Brescia, Italy.

3 Unit of Infectious Diseases, Carlo Poma Hospital, Mantova.

4 Microbiology and Virology Unit, University of Brescia and ASST Spedali Civili General Hospital, Brescia, Italy.

5 Institute of Microbiology and Virology, Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences, University of Milan, Italy.

*These Authors equally contributed to this work.

Corresponding

author: Emanuele Focà MD, PhD. Department of Infectious and Tropical

Diseases, Department of Clinical Experimental Sciences. The University

of Brescia and Brescia Spedali Civili General Hospital. Piazzale

Spedali Civili, 1, 25123 Brescia (Italy). E-mail:

emanuele.foca@unibs.it

Published: July 1, 2018

Received: March 23, 2018

Accepted: May 14, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018040 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.040

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Progressive

disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) is an AIDS-defining illness with a

high lethality rate if not promptly treated. The wide range of its

possible clinical manifestations represents the main barrier to

diagnosis in non-endemic countries. Here we present a case of PDH with

haemophagocytic syndrome in a newly diagnosed HIV patient and a

comprehensive review of disseminated histoplasmosis focused on

epidemiology, clinical features, diagnostic tools and treatment options

in HIV-infected patients.

|

Introduction

Histoplasmosis is a mycosis resulting from the inhalation of the spores of the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma spp, which is a member of the family Ajellomycetaceae, a fungal group whose members may all cause systemic disease in otherwise healthy humans (Blastomyces, Coccidioides, Paracoccidioides).[1]

Although only occasionally reported in the pre-HIV-infection era, it

became a public health issue after the AIDS pandemic, being listed by

Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) among the

AIDS-defining illnesses in 1987.[2]

In the

immunocompetent host, exposure to Histoplasma microconidia is usually

responsible for a symptomless presentation or flu-like syndrome, as the

spores are contained by alveolar macrophages and subsequently cleared

by the activation of the adaptive immunity, especially the Th1

response. In the immunocompromised host, due to Th1 to Th2 shift, the

pathogen can invade the bloodstream and spread to other organs and

tissues, leading to progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH), a

fatal disease in untreated patients.[3,4]

The PDH

incidence in HIV patients peaked in 1992, and then gradually declined

following the introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART).

It is currently a health issue especially in countries where cART is

not widely available. In Europe, it is only sporadically reported,[5] mainly in migrants from endemic areas.[6]

In

the last years, in Italy, we observed an increase in the proportion of

AIDS cases in migrants: they account now for more than 1/3 of the new

HIV-infection diagnosis and, among them, the 68% comes from Africa and

Latin America.[7]

We believe that it is important

to raise the awareness of histoplasmosis also at our latitude, given

the recent increase of the migratory fluxes from endemic countries and

the high risk of fatal outcome associated with late diagnosis and

treatment.

Here we will present a case of a newly diagnosed AIDS

patient, previously suspected to have lymphoma with haemophagocytic

syndrome. Both microbiological and histological examinations revealed

disseminated histoplasmosis. Furthermore, we provide a comprehensive

review of the current literature on histoplasmosis in HIV-infected

patients focusing on epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic features and

treatment options.

Case-Report

In

February 2016, a 19-year-old woman coming from Ivory Coast was admitted

to a peripheral hospital of our city for persistent fever. After she

resulted positive for a screening HIV-Ab test, she was referred to the

Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department. At admission she had deep

asthenia, chills, fever (max 38.8°C), and tachycardia (110 bpm);

examination revealed mono-lateral tonsillar hypertrophy and

submandibular lymphadenopathy. Laboratory investigations showed

pancytopenia (haemoglobin 8.7 g/dL - normal value 12.0-16.0 g/dL, white

blood cells 3,050/µL -n.v. 4.00-10.80x103/µL, platelets 80,000/µL - n.v. 130-400x103/µL),

increased lactate dehydrogenase (5,201 U/L - n.v. 136-234 U/L),

increased levels of C Reactive Protein (63.3 mg/L - n.v. < 5.0

mg/L), and high ferritin and triglycerides serum levels (> 40,000

ng/mL and 440 mg/dL - n.v. 20-120 ng/mL and <150 mg/dL

respectively). Baseline lymphocytes CD4+ T-cell count was 19 cell/µL

and HIV-RNA was 1,787,000 cp/mL. In addition, the patient resulted

positive for EBV-DNA (1,297 cp/mL), CMV-DNA (266 cp/mL), and HBV-DNA

(> 700,000,000 UI/mL), and for blood stool test. Suspecting a

lymphoproliferative disorder evolving in haemophagocytic syndrome, a

bone marrow biopsy was performed and steroid treatment was started.

Consequently, we performed biopsies of the gut, lateral-cervical lymph

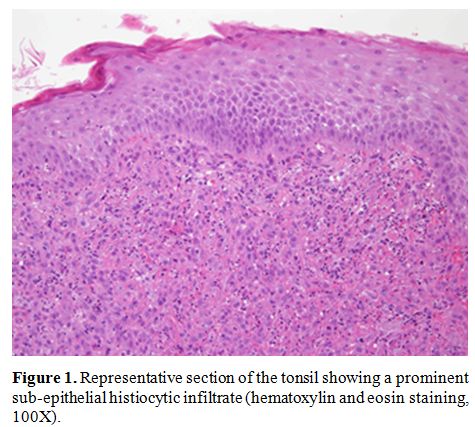

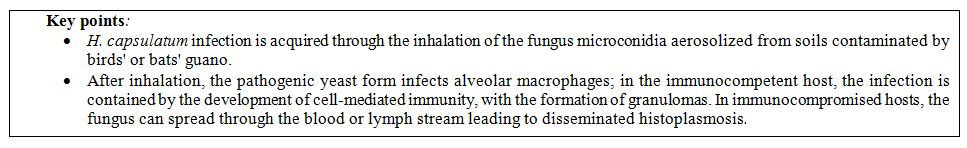

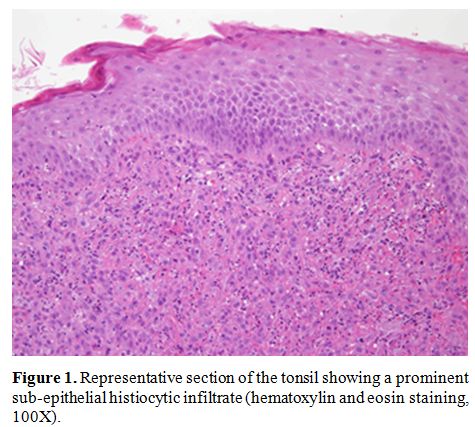

node, and tonsil. Microscopical evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E) sections of the bone marrow showed a prominent

lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with budding yeast cells inside

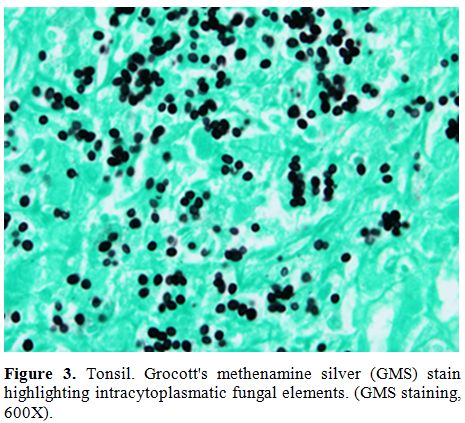

macrophages, suggestive of histoplasmosis, which was confirmed by

Grocott Methenamine Silver stain (GMS) and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)

stain. Antifungal treatment with liposomal Amphotericin B was started

while steroid therapy was gradually reduced. She rapidly became

afebrile and, in the following weeks, we observed a slow regression of

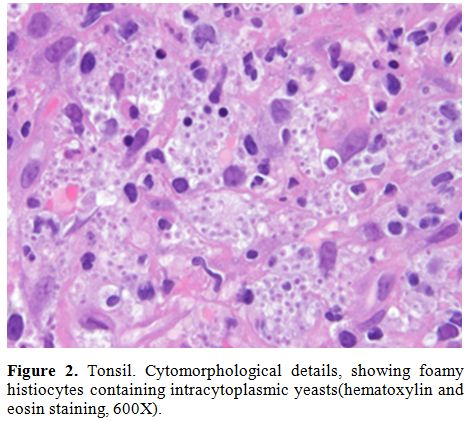

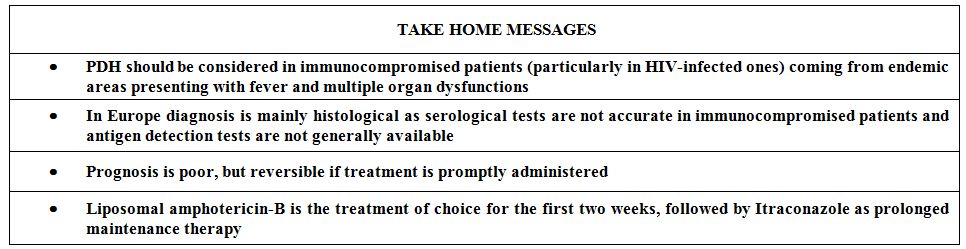

symptoms. Histological examination of submandibular lymph node, tonsil

and colic mucosa also confirmed the diagnosis (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Histoplasma spp serology was negative, while culture of bone marrow aspirate showed H. capsulatum

growth. After three weeks of induction therapy, she continued on

maintenance therapy with itraconazole, and cART with

tenofovir/emtricitabine + dolutegravir was prescribed. The patient was

referred to the Outpatient Clinic. She attended at the first follow-up

visit ten days after the hospital discharge with improved clinical

conditions and blood exams.

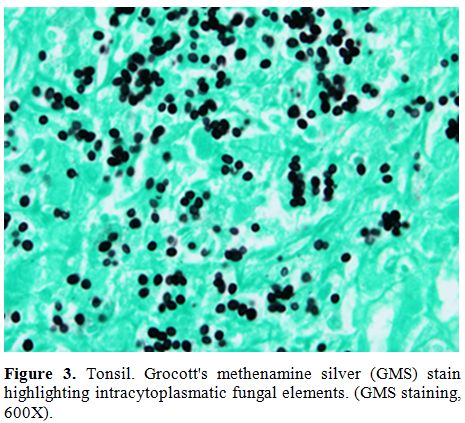

|

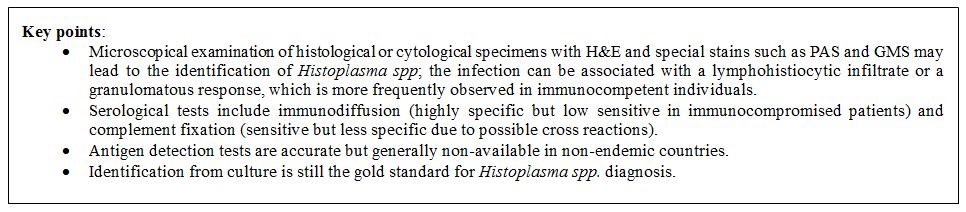

Figure 1.

Representative section of the tonsil showing a prominent

sub-epithelial histiocytic infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin staining,

100X). |

|

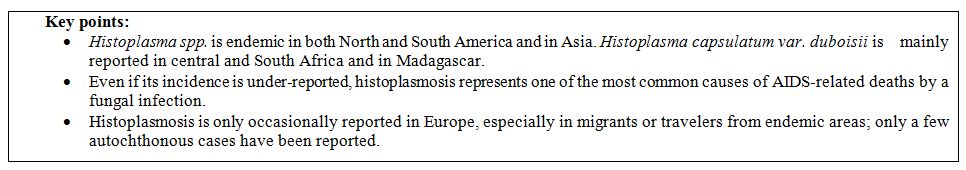

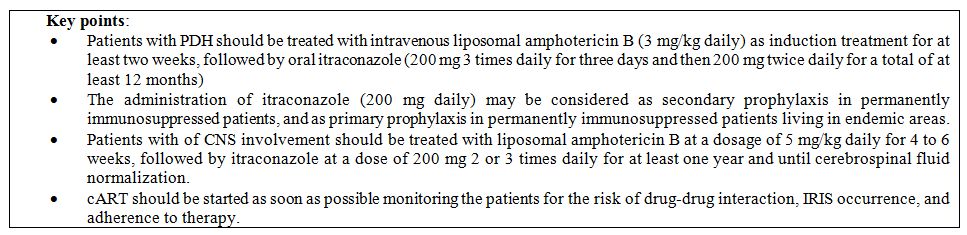

Figure 2. Tonsil.

Cytomorphological details, showing foamy histiocytes containing

intracytoplasmic yeasts(hematoxylin and eosin staining, 600X). |

|

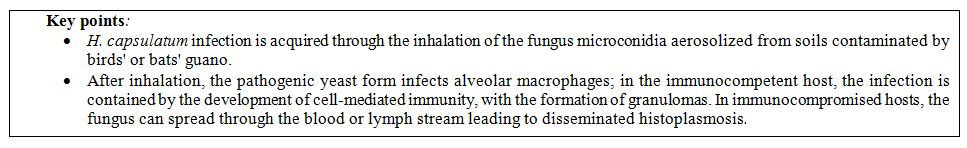

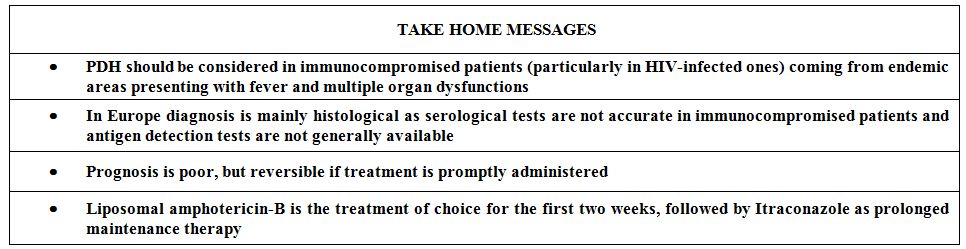

Figure 3. Tonsil. Grocott's methenamine

silver (GMS) stain highlighting intracytoplasmatic fungal elements.

(GMS staining, 600X). |

However

in April 2016 she returned to Ivory Coast and was re-linked to care in

October 2016. At the time of the visit lymphocytes CD4+ T count was 29

cell/µL, HIV-RNA was 153,300 cp/mL and HBV DNA was 212,600,000 UI/mL.

During her stay in Ivory Coast, she interrupted both antiretroviral

therapy and histoplasmosis maintenance therapy; moreover, at the moment

of the new visit she was pregnant and after proper counseling, she

decided to carry on the pregnancy. Only antiretroviral therapy with

tenofovir/emtricitabine + atazanavir/ritonavir was re-started and a

close follow-up was scheduled. After three weeks she was admitted to

the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for internal abortion, complicated by

septic shock. She was treated with wide spectrum antibiotic therapy

(meropenem and vancomycin) without any microbiological isolation and

she went through several transfusions and mechanical ventilation. Once

stabilized, she was transferred to our Department, she was febrile,

pancytopenic and with a skin lesions on her chest, suggestive of

histoplasmosis reactivation so that antifungal treatment with liposomal

Amphotericin B was reintroduced. Bone marrow biopsy confirmed the

suspect. The same day antiretroviral therapy with

tenofovir/emtricitabine + dolutegravir was reintroduced. In the

following weeks, a slow progressive improvement of the conditions was

observed, therefore she was transferred to a facility with proper

social support and health assistance. At the time of the last visit in

December 2017, the patient was asymptomatic and fully adherent with

cART and histoplasmosis prophylaxis. Last CD4+ T-cell count was 150

cell/µL and a low-level viral load was detected for HIV and HBV (33

copies/mL and 95 UI/mL respectively).

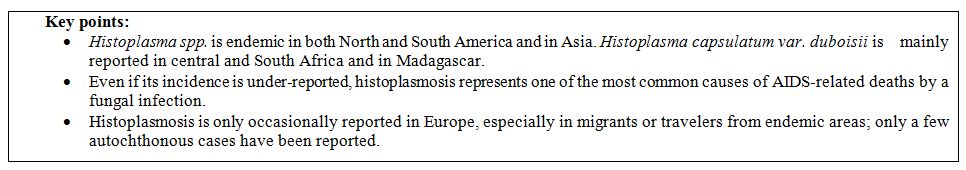

Epidemiology

Histoplasma capsulatum

is recognized as a pathogen with worldwide distribution, with many

cases registered outside the historically known endemic areas of the

Americas.[8,9] Many countries of the American

continent are considered highly endemic as revealed by outbreak reports

and skin reactivity studies. In the United States, histoplasmin

sensitivity ranges from 60% to 90% in Ohio and in the Mississippi river

valley, while in Latin America the prevalence of H. capsulatum

infection is reported as 50% in some Panama’s areas, reaching 93% in

specific places of Brazil as in Ilha do Governador, Rio de Janeiro.[10] H. capsulatum is also endemic in Asia, where autochthonous cases have been reported since the seventies.[11] H. capsulatum var. duboisii has been isolated in Central and West areas of Africa and in Madagascar.[12]

Sporadic cases of histoplasmosis have been reported in Europe, mainly

in immigrants or travelers returning from endemic areas. Reports of

autochthonous cases in Europe suggest the possible endemic presence in

some European areas, such as the south of France and the Po river

valley in Italy.[13,14] Since the HIV/AIDS pandemic

spread out, many cases of histoplasmosis have been reported in

HIV-infected patients in locations with few previously reported cases.

In endemic areas, such as Latin America, PDH is one of the most common

causes of AIDS-related deaths, however, it remains underestimated due

to misdiagnosis and lack of first choice antifungal therapy.[15] Fungal infections were estimated to be responsible of 47% of over 1,500,000 AIDS-related death in 2013, and, among them, Histoplasma was the third responsible pathogen, after Pneumocystis jiroveci and Cryptococcus neoformans.[16] Some authors recently reported an increase in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in AIDS-patients in Latin America.[17] In

some areas, the situation appears dramatic: histoplasmosis is one of

the first causes of death in HIV-infected patients in French Guiana,

with a lethality of more than 50%; in Fortaleza, Brazil, almost a half

(43%) of hospitalized HIV-infected patients had PDH.[6]

In other known endemic areas, such as Africa, there is a lack of data

about the incidence of PDH. A recent study estimated that targeting

opportunistic fungal infections through diagnostic and therapeutic

tools access could be a crucial factor in reducing AIDS-related deaths,

saving more than a million lives over five years.[16]

In

non-endemic areas as in Europe, most PDH cases are reported in

HIV-infected migrants. From 1984 to 2004, 72 patients with

HIV-associated histoplasmosis were reported in Europe, mostly observed

in Italy; among them, 7 cases were autochthonous.[18]

|

|

Pathogenesis

H. capsulatum is

a dimorphic fungus that displays different morphologies depending on

environmental conditions: the mold in the soil and the budding yeast in

the mammalian host. H. capsulatum

infection is usually acquired through inhalation of microconidia

aerosolized from environmental sites hosting the fungus. The

saprophytic form seems to grow best in soils with a high nitrogen

content associated with the presence of birds and bats guano. Some

activities, such as demolition and construction works, archaeological

and speleological works or poultry farming, have been associated with

an increased risk of infection because they can lead to microconidia

exposure. Infection with the yeast form via tissue transplant,

laboratory accident or needle sharing has also been described. After

inhalation, the fungus reaches the alveolar space where it finds

favorable temperature; there it turns into the pathogenic yeast form

and begins his intracellular life in alveolar macrophages.[19]In

the absence of immune-compromising conditions, acute infection resolves

with the development of cell-mediated immunity. An antigen-specific

CD4+ T lymphocyte-mediated response leads to the formation of

granulomas; this immune activation can contain the fungus and protect

against reinfection, but it is not able to eradicate the pathogen. The

development of specific cell-mediated immune response results in a

delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that can be induced by

intradermal injection of fungal antigens (histoplasmin skin test).[20]

In healthy individuals, the primary infection is usually asymptomatic

or mild-symptomatic, resulting in a self-limiting and non-specific

febrile syndrome with respiratory involvement. H.capsulatum

establishes a long-lasting quiescent infection that can reactivate in

case of immune system weakening, such as in advanced HIV infection,

chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy for transplants or autoimmune

diseases. Host-pathogen balance plays a crucial role in infection

course; when cell-mediated immunity is compromised the fungus moves

from the primary site to the whole body through the blood and lymph

stream or within cells as macrophages but also dendritic cells and

neutrophils, leading to disseminated disease.[21] The

main affected organs are liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and

bone marrow. In addition to the immune status of the host, other

factors potentially involved in the evolution of Histoplasma infection are the number of organisms inhaled and the strains virulence.[22]

|

|

Clinical Features

Histoplasmosis

has a very heterogeneous clinical presentation, ranging from mild and

self-limiting respiratory syndromes to disseminated forms with high

lethality rate, depending on immune system conditions.[19]

In most cases, the infection is completely asymptomatic or may be

associated with a non-specific syndrome characterized by fever, chills,

cough and chest pain. Rheumatologic manifestations including arthritis,

arthralgia, and erythema nodosum have also been described in a small percentage of cases.[23,24]

In endemic areas, peculiar forms of histoplasmosis have been described,

such as ocular histoplasmosis with chorioretinal involvement and

“histoplasmoma,” a slow enlarging lung nodule.[25,26] In

immunocompromised host, a deficit in cellular immunity can lead to

fungus dissemination, massive organ involvement and severe systemic

disease (PDH). PDH is usually diagnosed in the late stage of HIV

infection; however, some rare cases have been reported in other

conditions, such as hematologic patients[27,28] and even in immune-competent individuals living in developing countries.[29] Mortality rate reaches 39% in endemic areas, such as Latin America[10] but is even higher in non-endemic areas like Europe, where the disease is often misdiagnosed.[8]

PDH usually presents with persistent fever, deep asthenia, and weight

loss; diarrhea and other digestive symptoms are often described since

gastrointestinal tract is a frequent site of fungus dissemination.

Reticuloendothelial system is the main organ affected in PDH with

severity ranging from isolated lymphadenopathy, hepato- and

spleno-megaly to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). HLH is a

life-threatening disease in which a massive immune stimulation results

in macrophages activation and hemophagocytosis; it is a rapidly

progressive syndrome with non-specific symptoms so that it can mimic

many different etiologies: malaria (if patient has a recent history of

travel in endemic areas),[30] sepsis, hepatic failure, hematologic disorders and malignancies among others.[31]

Fever, splenomegaly, deep pancytopenia, altered liver function with

hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia and increased ferritin level

are the main clinical diagnostic criteria.[32] According to a recent review, 27 cases of HLH secondary to PDH were reported so far, with a mortality rate of 38%.[33]

Up to 10% of patients with PDH may develop central nervous system (CNS)

involvement as a primary manifestation or relapsing disease.[34]

Neurologic dissemination of the pathogen may occur as subacute or

chronic meningitis, focal neurologic deficit and encephalitis.[35,36] Skin involvement in PDH has been reported in up to 25% of AIDS patients.[37]

Dermatologic findings are not specific: papules, plaques, and nodules

are commonly described, usually affecting trunk and face. Mucosal

involvement is often reported, especially as painful and infiltrated

ulcers in oral mucosa.[38] Other less common manifestations of PDH include endocrine syndromes, such as chronic adrenal insufficiency,[39] and myositis, of which only 4 cases were reported so far.[40]

In AIDS patients from endemic areas starting cART, a few cases of

immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) revealing PDH have

been described: fever, weight loss, and lymphadenitis were the main

symptoms in these reports.[41] The

recognition of PDH in AIDS may be challenging since most patients have

other concomitant opportunistic infections, especially those with CD4+

counts <150 cells/mL: pneumocystosis, cryptococcosis, and

mycobacteriosis are the main reported co-infections.[42]

Diagnostic Tools

There

are multiple methods for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis including

histopathology or cytology, direct examination using specific fungal

stains, cultures, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization – Time Of

Flight (MALDI-TOF), antigen detection, immunization determination,

serological tests and molecular biology-based tests. Only hospitals

with a dedicated mycology sector in their laboratory allow the most

rapid and accurate diagnosis. It is worth noting that managing cultures

of Histoplasma spp, as for

other dimorphic fungi, requires a biosafety level 3 or 4 with class II

or III biological safety cabinets, and laboratory personnel involved

with Histoplasma cultures should use appropriate procedures to prevent exposure.Each

of the available tests is designed and performed for specific

histoplasmosis syndromes depending on the patient condition or level of

immunosuppression, but all can be used to complete the diagnostic path.

The diagnostic methods not only differ in sensibility and specificity

but also in time-to-response, total cost, quality of the information,

and have certain limitations that must be recognized if they are to be

used correctly.Histopathology. The diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be obtained through examination of histological or cytological specimens.[43]

Histological specimens from tissue biopsies of different anatomical

sites stained with H&E and special stains such as PAS and GMS can

be used. Cytological specimens of bone marrow aspirates stained with

Giemsa,[44] fluids [45] (ex. bronchoalveolar lavage) or tissues[46] (lung, lymph nodes, spleen, cutaneous lesions, etc.) can also be utilized. There are two different forms of H. capsulatum causing human histoplasmosis; H. capsulatum var. capsulatum and H. capsulatum var. duboisii but the two are difficult to distinguish. In H&E stains H. capsulatum

is characterized by the presence of a clear space or artefactual halo,

due to the retraction of basophilic cell cytoplasm from the cell wall.

Budding yeasts, usually difficult to identify, are connected to a

narrow base, a feature that helps the distinction of H. capsulatum from other fungi.[47,48]In

specimen, it can be highlighted with different staining methods:

Romanowsky-type stains, Giemsa, Wright-Giemsa stains, Grocott-Gömöri

methenamine–silver (GMS), mucicarmine, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)

stains and Gram stains. GMS, PAS and mucicarmine are the most commonly

used. GMS and PAS provide contrast to yeast cells showing black-colored

and magenta-colored intracellular or extracellular yeasts respectively;

at mucicarmine stain, the yeast forms are barely visible. H. capsulatum must be distinguished, in particular, from other fungi such as a small variant of Blastomyces dermatitidis, capsule-deficient Cryptococci, endospores of Coccidioides spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii, and Candida glabrata.[49,50]H. capsulatum should also be distinguished from protozoa, like Leishmania spp (amastigotes), Toxoplasma gondii (bradyzoites) and Trypanosoma cruzi (amastigotes). The patient histological reaction to H. capsulatum

infection varies according to the severity and phase of the infection

and the host's immune system. In the acute phase, subsequent to

pulmonary infection, H. capsulatum

may be seen within alveolar space and in the interstitium, inside

macrophages. Usually, there is an associated lymphohistiocytic

infiltrate with necrosis and vasculitis. The histopathologic picture

resembles lymphomatoid granulomatosis, but scattered small granulomas

with small yeasts in the parenchyma should suggest the diagnosis of

histoplasmosis.[51]In

chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, the most common host's reaction is a

necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with a low number of organisms,

resulting in nonviable (culture-negative) yeast. Special stains are

needed to detect Histoplasma in this setting since it cannot usually be visualized on H&E.In

disseminated histoplasmosis, there is extensive tissue infiltration by

organisms, and usually, the host's tissue reaction is poor, and it can

be represented by a subtle inflammatory associated with extensive tissue

necrosis.It

is important to remember that histoplasmosis can induce a variety of

organ-site responses with unfamiliar or unusual histological patterns,

and the diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be missed if the clinicians do

not provide adequate clinical data.[52] In

particular, when evaluating tissue lesions from patients with profound

immunodepression, histological tissues examination should include

special histochemical stains for infectious agents.[53]Microbiology. Microscopy:

The diagnosis of invasive histoplasmosis can be obtained through

various direct examination methods. The major part of collected

specimens can be freshly prepared on a wet mount and examined.[54,55,56]Direct

microscopic examination of the clinical specimen is a simple but useful

method to provide a rapid hint on the possible presence of fungal

infection. The limit of microscopy is the low specificity due to the

similarity between the different fungal species.[57,58] H. capsulatum can be easily misidentified with B. dermatitidis, various Candida species, Cryptococcus gattii, Cryptococcus neoformans, Talaromyces marneffei, and endospores of Coccidioides species.[59]Culture methods: H. capsulatum

is a dimorphic fungus: at temperatures above 30°C, there is the yeast

phase while in the cultures incubated at lower temperatures (25°C)

there is the development of mold phase. The yeast phase allows a fast

growth of the isolate, with an average growth time of 5-7 days; the

mold phase takes from 4 weeks to up to 12 weeks to grow.The

gold standard for the identification of the pathogen is the culture

demonstrating the thermal dimorphism of the fungus from yeast to mold

and vice versa.Isolation

from samples from the lower respiratory tract with bronchial and

bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in cases of chronic pulmonary

histoplasmosis has a sensitivity of 60-75%. In the case of disseminated

histoplasmosis, isolation through blood culture is the most sensitive

method while the sensitivity of bone marrow culture is 75%.[59,60]The

use of MALDI-TOF technology is a method of direct identification of the

colony of both the yeast phase and the mold phase, capable of providing

rapid detection of H. capsulatum with excellent sensitivity, greatly reducing diagnosis times, but until now only a scarce data have been published so far.[61]Non–culture methods:

Many non-culture methods were developed in order to make a correct and

rapid diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Other tests such as the research of

beta-3-D-glucan or the Platelia test (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond,

WA) for Aspergillus can cross-react in case of histoplasmosis and are

not to be considered specific.[62]Antibody

detection methods: Most of these assays are based on the ability to

search for antibodies to histoplasmin (HMIN). HMIN has three antigens.

It is an extremely specific test (100%), but sensitivity is reduced

(70-100%) depending on the type of infection and the patient’s level of

immune depression. The

complement fixation test is a more sensitive method (94.3%) but less

specific (70%) than immunodiffusion; however, use of this test is of

little help in immunocompromised or AIDS patients. A Semi-Quantitative

Indirect Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) testing for IgM and IgG against the

Histoplasma polysaccharide antigen is available by Mira-Vista

Diagnostics (Indianapolis, Indiana). It is validated on both serum and

CSF; false negative results may result in some progressive or chronic

cases, especially in immunocompromised patients. A western-blot test

has recently been validated in Brazil, providing sensitive, specific,

and faster results.[63]Antigen detection: Enzyme immunoassay is a quantitative test which detects the presence of Histoplasma

polysaccharide with a reported sensibility of up to 95%. The antigen is

present in larger quantities in the urine than in the serum and the

sensitivity of the test increases in immunocompromised patients and in

disseminated histoplasmosis. An indication of response to therapy is

the decrease over time of the urinary antigen.[64,65]An antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect H. capsulatum antigenuria in immunocompromised has been validated and distributed by the CDC. Some other antigen-based tests for Aspergillus spp. have been proposed and showed promising accuracy on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid .[66,67,68]Molecular tools:

The absence of commercially available FDA-approved molecular tests has

led to the development of multiple homemade solutions from conventional

PCR to semi-nested, nested, real-time, LAMP, and RCA.[69,70,71,72]

Therapeutic and Preventive Approach

Guidelines

from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the HIV

Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America

(IDSA) recommend treatment with intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin

B (3 mg/kg daily) as induction treatment for at least 2 weeks, or up to

a clinical improvement and a possibility of oral treatment.[73]Amphotericin

B lipid complex and Amphotericin B deoxycholate may represent a less

expensive alternative in patients with a low risk of nephropathy;[74]

given the risk of nephrotoxicity and the high number of interaction

with other compounds, the patient should be strictly monitored during

induction therapy particularly for the renal function and electrolytes

balance. After

induction therapy, the treatment should be prolonged with oral

itraconazole (200 mg 3 times daily for three days and then 200 mg twice

daily for at least 12 months).Additionally,

long-term suppressive therapy with itraconazole (200 mg daily) may be

considered in permanently immunosuppressed patients and in patients

with recurrent symptoms of PDH. Even though the timing of

secondary prophylaxis is still unclear, few data suggest it should be

prolonged for one year and until the CD4+ T-cell count reaches 150

cells/mm3 and the patient is on effective cART for at least six months.Itraconazole

200 mg daily is also recommended as primary prophylaxis for

HIV-infected patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <150 cells/mm3 living in highly endemic areas or with potential occupational exposure to the fungus.[75]Among

other azoles, fluconazole at a dosage of 800 mg daily may be used as an

alternative regimen in patients who can't be treated with itraconazole,

but showed a lower effectiveness and a higher risk of developing

resistance. In addition, the administration of posaconazole and

voriconazole seems to be effective but current literature offers only a

few experiences in the usage of these antimycotic agents. Echinocandins

are not active against Histoplasma spp and should not be used. In

case of CNS involvement liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 5 mg/kg

daily for 4 to 6 weeks should be used as initial therapy, followed by

itraconazole at a dose of 200 mg 2 or 3 times daily for at least one

year and until cerebrospinal fluid normalization.The

cART should also be started as soon as possible, but in severe forms,

it can be delayed since the resolution of the acute phase to prevent

the potential development of IRIS. There

is a lack of data regarding the better antiretroviral regimen to

administer in these patients; however, a high genetic barrier drugs, as

well as unboosted regimens, should be preferred according to possible

drug-drug interactions between antiretroviral and antifungal treatment.

Protease inhibitor-based regimens may be chosen for their potency and

high genetic barrier, but they are not free from interactions because

of their boosting need (with ritonavir or cobicistat). The

administration of the new class of integrase inhibitors guarantees a

low risk of drug-drug interactions and a rapid viral load decline.

Nonetheless, among them, raltegravir does not have a high genetic

barrier, elvitegravir is boosted by cobicistat, and only a few data are

available on dolutegravir, and all these drugs are less available in

resource-limited countries.[76]Lastly, possible drug-drug interactions and adherence to cART should be strictly monitored by physicians.[77]

Conclusions

PDH

carries a poor prognosis, especially when the diagnosis is delayed;

giving its rarity in non-endemic areas and the variety of its clinical

presentation, along with the restricted range of sensitive tests in

non-endemic countries it poses a real challenge to clinicians.

We

are nowadays experiencing an increase in migratory flows from tropical

areas, especially those where cART is not widely available. This

phenomenon could raise the probability to encounter AIDS-related

diseases previously only anecdotal at our latitude in the daily

clinical practice.

In our case, the prompt diagnosis was possible

only thanks to direct microscopy identification since serology was

negative, due to the deep immunosuppression of the patient.

Prognosis may be favorable when antifungal therapy and cART are

promptly administered; the co-administration of steroid treatment may

be necessary when associated with HLH or immune-reconstitution

syndrome. In our case, the adequate combined treatment (antifungal,

antiretroviral and steroidal) allowed a good clinical outcome, also if

the relapse after an early interruption of the secondary prophylaxis

highlights the need of a prolonged course of antifungal maintenance

therapy.

Early diagnosis remains crucial to guarantee the survival

of the patients, and we believe that the improvement of surveillance on

this disease represents the best tool to reach this endpoint also in

non-endemic countries.

|

|

References

- Köhler JR, Hube B, Puccia R, Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Fungi that Infect Humans. Microbiol Spectr. 2017 Jun;5(3). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0014-2016 PMid:28597822

- Subedee

A, Van Sickels N. Hemophagocytic Syndrome in the Setting of AIDS and

Disseminated Histoplasmosis: Case Report and a Review of Literature. J

Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015 Sep-Oct;14(5):391-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957415570740 PMid:25670709

- Horwath MC, Fecher RA, Deepe GS Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(6):967-75. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.15.25 PMid:26059620 PMCid:PMC4478585

- Jones

JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Alderton DL, Fleming PL, Kaplan JE, Ward J

Surveillance for AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses, 1992-1997. MMWR

CDC Surveill Summ. 1999 Apr 16;48(2):1-22. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.135.8.897

- Martin-Iguacel

R, Kurtzhals J, Jouvion G, Nielsen SD, Llibre JM. Progressive

disseminated histoplasmosis in the HIV population in Europe in the

HAART era. Case report and literature review. Infection. 2014

Aug;42(4):611-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-014-0611-7 PMid:24627267

- Daher

EF, Silva GB Jr, Barros FA, Takeda CF, Mota RM, Ferreira MT, Oliveira

SA, Martins JC, Araújo SM, Gutiérrez-Adrianzén OA. Clinical and

laboratory features of disseminated histoplasmosis in HIV patients from

Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2007 Sep;12(9):1108-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01894.x PMid:17875020

- Istituto

Superiore di Sanità. Aggiornamento delle nuove diagnosi di infezione da

HIV e dei casi di AIDS in Italia al 31 Dicembre 2016.

- Bahr

NC, Antinori S, Wheat LJ, Sarosi GA. Histoplasmosis infections

worldwide: thinking outside of the Ohio River valley. Curr Trop Med

Rep. 2015 Jun 1;2(2):70-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-015-0044-0 PMCid:PMC4535725

- Benedict

K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of Histoplasmosis Outbreaks, United States,

1938-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):370-8. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2203.151117 PMid:26890817 PMCid:PMC4766901

- Colombo

AL, Tobón A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of

endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011

Nov;49(8):785-98. https://doi.org/10.3109/13693786.2011.577821

- Wang

TL1, Cheah JS, Holmberg K. Case report and review of disseminated

histoplasmosis in South-East Asia: clinical and epidemiological

implications. Trop Med Int Health. 1996 Feb;1(1):35-42. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-10.x PMid:8673821

- Gugnani HC. Histoplasmosis in Africa: a review. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2000 Oct-Dec;42(4):271-7. PMid:15597674

- Confalonieri

M1, Nanetti A, Gandola L, Colavecchio A, Aiolfi S, Cannatelli G, Parigi

P, Scartabellati A, Della Porta R, Mazzoni A. Histoplasmosis capsulati

in Italy: autochthonous or imported? Eur J Epidemiol. 1994

Aug;10(4):435-9. PMid:7843347

- Ashbee

HR, Evans EGV, Viviani MA, Dupont B, Chryssanthou E, Surmont I, et al.

Histoplasmosis in Europe: report on an epidemiological survey from the

European Confederation of Medical Mycology Working Group. Med Mycol.

2008;46:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780701591481 PMid:17885939

- Centers

for Disease Control. Revision of the CDC Surveillance Case Definition

of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. MMWR 1987; 36 (Suppl. No 36).

- Denning

DW. Minimizing fungal disease deaths will allow the UNAIDS target of

reducing annual AIDS deaths below 500 000 by 2020 to be realized.

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016 Dec 5;371(1709)

.

.

- López

Daneri GA, Arechavala A, Iovannitti CA, Mujica MT. Histoplasmosis

diseminada en pacientes HIV/SIDA: Buenos Aires, 2009-2014. Medicina.

76. 2016; 332-337.

- Antinori

S1, Magni C, Nebuloni M, Parravicini C, Corbellino M, Sollima S,

Galimberti L, Ridolfo AL, Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis among human

immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and

review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006 Jan;85(1):22-36 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.md.0000199934.38120.d4 PMid:16523050

- Woods

JP. Revisiting old friends: Developments in understanding Histoplasma

capsulatum pathogenesis. J Microbiol. 2016 Mar;54(3):265-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-016-6044-5 PMid:26920886

- Woods

JP1, Heinecke EL, Luecke JW, Maldonado E, Ng JZ, Retallack DM,

Timmerman MM. Pathogenesis of Histoplasma capsulatum. Semin Respir

Infect. 2001 Jun;16(2):91-101. PMid:11521241

- Taylor

ML, Díaz S, González PA, Sosa AC, Toriello C. Relationship between

pathogenesis and immune regulation mechanisms in histoplasmosis: a

hypothetical approach. Rev Infect Dis. 1984 Nov-Dec;6(6):775-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/6.6.775 PMid:6240756

- Sepúlveda

VE, Williams CL1, Goldman WE2. Comparison of phylogenetically distinct

Histoplasma strains reveals evolutionarily divergent virulence

strategies. MBio. 2014 Jul 1;5(4):e01376-14. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01376-14 PMCid:PMC4161242

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Jan;20(1):115-32. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00027-06 PMid:17223625 PMCid:PMC1797635

- Sizemore TC. Rheumatologic manifestations of histoplasmosis: a review. Rheumatol Int. 2013 Dec;33(12):2963-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-013-2816-y PMid:23835880

- Unis G, Pêgas KL, Severo LC. [Pulmonary histoplasmoma in Rio Grande do Sul]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005 Jan-Feb;38(1):11-4. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822005000100003 PMid:15717088

- Diaz RI, Sigler EJ, Rafieetary MR, Calzada JI. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015 Jul-Aug;60(4):279-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.02.005 PMid:25841248

- Oliveira

CC. Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma in Mediastinum Lymph Nodes and Lung

Associated to Histoplasmosis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphoid

Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2017 Jun 20;9(1):e2017044. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2017.044 PMid:28698787 PMCid:PMC5499492

- Garbee

DD, Pierce SS, Manning J. Opportunistic Fungal Infections in Critical

Care Units. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2017 Mar;29(1):67-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnc.2016.09.011 PMid:28160958

- De

D, Nath UK. Disseminated Histoplasmosis in Immunocompetent Individuals-

not a so Rare Entity, in India. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2015 Apr

20;7(1):e2015028. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2015.028 PMid:25960856 PMCid:PMC4418405

- Focà

E, Odolini S, Brianese N, Carosi G. Malaria and hiv in adults: when the

parasite runs into the virus. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2012;4(1):e2012032. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2012.032 PMid:22708047 PMCid:PMC3375742

- Adenis

A, Nacher M, Hanf M, Vantilcke V, Boukhari R, Blachet D, Demar M, Aznar

C, Carme B, Couppie P. HIV-associated histoplasmosis early mortality

and incidence trends: from neglect to priority. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.

2014 Aug 21;8(8):e3100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003100 PMid:25144374 PMCid:PMC4140672

- Untanu

RV, Akbar S, Graziano S, Vajpayee N. Histoplasmosis-Induced

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in an Adult Patient: A Case Report

and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:1358742. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1358742

- Henter

JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S,

McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and

therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr

Blood Cancer. 2007 Feb;48(2):124-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21039 PMid:16937360

- Townsend

JL, Shanbhag S, Hancock J, Bowman K, Nijhawan AE.

Histoplasmosis-Induced Hemophagocytic Syndrome: A Case Series and

Review of the Literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015 Apr

15;2(2):ofv055. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofv055

- Nyalakonda

H, Albuerne M, Suazo Hernandez LP, Sarria JC. Central Nervous System

Histoplasmosis in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Am J Med Sci.

2016 Feb;351(2):177-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2015.11.016 PMid:26897273

- Wheat

LJ, Musial CE, Jenny-Avital E. Diagnosis and management of central

nervous system histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar

15;40(6):844-52. https://doi.org/10.1086/427880 PMid:15736018

- Soza

GM, Patel M, Readinger A, Ryan C. Disseminated cutaneous histoplasmosis

in newly diagnosed HIV. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016

Jan;29(1):50-1.36 Klein IP, Martins MA, Martins MD, Carrard VC.

Diagnosis of HIV infection on the basis of histoplasmosis-related oral

ulceration. Spec Care Dentist. 2016 Mar-Apr;36(2):99-103.

- Koene

RJ, Catanese J, Sarosi GA. Adrenal hypofunction from histoplasmosis: a

literature review from 1971 to 2012. Infection. 2013 Aug;41(4):757-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-013-0486-z PMid:23771479

- Nimitvilai

S, Thammaprasert W, Vinyuvat S. Histoplasmosis myositis: a case report

and literature review. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2015

Jul;46(4):738-42. PMid:26867394

- Mambie

A, Pasquet A, Melliez H, Bonne S, Blanc AL, Patoz P, Ajana F. A case of

immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome related to a disseminated

histoplasmosis in an HIV-1 infected patient. AIDS. 2013 Aug

24;27(13):2170-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000432448.53110.e3 PMid:24384595

- Silva

TC, Treméa CM, Zara AL, Mendonça AF, Godoy CS, Costa CR, Souza LK,

Silva MR. Prevalence and lethality among patients with histoplasmosis

and AIDS in the Midwest Region of Brazil. Mycoses. 2017

Jan;60(1):59-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12551 PMid:27625302

- Gupta

N, Arora SK, Rajwanshi A, Nijhawan R, Srinivasan R. Histoplasmosis:

cytodiagnosis and review of literature with special emphasis on

differential diagnosis on cytomorphology. Cytopathology. 2010

Aug;21(4):240-4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00693.x PMid:19843140

- Qin

L, Zhao L, Tan C, Chen XU, Yang Z, Mo W. A novel method of combining

Periodic Acid Schiff staining with Wright-Giemsa staining to identify

the pathogens Penicillium marneffei, Histoplasma capsulatum, Mucor and

Leishmania donovani in bone marrow smears. Exp Ther Med. 2015

May;9(5):1950-1954. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2015.2357 PMid:26136921 PMCid:PMC4471769

- Mukunyadzi

P, Johnson M, Wyble JG, Scott M. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis in urine

cytology: reactive urothelial changes, a diagnostic pitfall. Case

report and literature review of urinary tract infections. Diagn

Cytopathol. 2002 Apr;26(4):243-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.10049 PMid:11933270

- Goldani

LZ, Klock C, Diehl A, Monteiro AC, Maia AL. Histoplasmosis of the

thyroid. J Clin Microbiol. 2000 Oct;38(10):3890-1. PMid:11015430

PMCid:PMC87503

- Koley

S, Mandal RK, Khan K, Choudhary S, Banerjee S. Disseminated Cutaneous

Histoplasmosis, an Initial Manifestation of HIV, Diagnosed with Fine

Needle Aspiration Cytology. Indian J Dermatol. 2014 Mar;59(2):182-5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.127681 PMid:24700939 PMCid:PMC3969680

- Rajeshwari

M, Xess I, Sharma MC, Jain D. Acid-Fastness of Histoplasma in Surgical

Pathology Practice. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017 Sep;51(5):482-487. https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2017.07.11 PMid:28934824 PMCid:PMC5611531

- Antinori S. Histoplasma capsulatum: more widespread than previously thought. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Jun;90(6):982-3. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0175 PMid:24778192 PMCid:PMC4047757

- Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, Spec A, Relich RF, Hage C. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):207-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.009 PMid:26897068

- Guarner

J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the

21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00053-10 PMid:21482725 PMCid:PMC3122495

- Mukhopadhyay

S, Katzenstein AL. Biopsy findings in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis:

unusual histologic features in 4 cases mimicking lymphomatoid

granulomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Apr;34(4):541-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d4388b PMid:20351490

- Ollague

Sierra JE, Ollague Torres JM. New clinical and histological patterns of

acute disseminated histoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency

virus-positive patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J

Dermatopathol. 2013 Apr;35(2):205-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0b013e31822fd00a PMid:22157244

- McLeod

DS, Mortimer RH, Perry-Keene DA, Allworth A, Woods ML, Perry-Keene J,

McBride WJ, Coulter C, Robson JM. Histoplasmosis in Australia: report

of 16 cases and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011

Jan;90(1):61-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e318206e499 PMid:21200187

- Baddley

JW, Sankara IR, Rodriquez JM, Pappas PG, Many WJ Jr. Histoplasmosis in

HIV-infected patients in a southern regional medical center: poor

prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Diagn

Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008 Oct;62(2):151-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.006 PMid:18597967

- Couppié

P, Aznar C, Carme B, Nacher M. American histoplasmosis in developing

countries with a special focus on patients with HIV: diagnosis,

treatment, and prognosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006 Oct;19(5):443-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qco.0000244049.15888.b9 PMid:16940867

- Akpek

G, Lee SM, Gagnon DR, Cooley TP, Wright DG. Bone marrow

aspiration,biopsy, and culture in the evaluation of HIV-infected

patients for invasive mycobacteria and histoplasma infections. Am J

Hematol. 2001 Jun;67(2):100-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.1086 PMid:11343381

- Nightingale

SD, Parks JM, Pounders SM, Burns DK, Reynolds J, Hernandez JA.

Disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS. South Med J.

1990Jun;83(6):624-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-199006000-00007 PMid:2356493

- Boyce

KJ, Andrianopoulos A.Fungal dimorphism: the switch from hyphae to yeast

is a specialized morphogenetic adaptation allowing colonization of a

host. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015 Nov; 39(6):797-811. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuv035 PMid:26253139

- Arango-Bustamante

K, Restrepo A, Cano LE, de Bedout C, Tobón AM, González A. Diagnostic

value of culture and serological tests in the diagnosis of

histoplasmosis in HIV and non-HIV Colombian patients. Am J Trop Med

Hyg. 2013 Nov;89(5):937-42. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.13-0117 PMid:24043688 PMCid:PMC3820340

- Prechter GC, Prakash UB. Bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of pulmonary histoplasmosis. Chest 1989; 95:1033. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.95.5.1033

- Chalupová

J, Raus M, Sedlářová M, Sebela M. Identification of fungal

microorganisms by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Biotechnol Adv. 2014

Jan-Feb;32(1):230-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.002 PMid:24211254

- Powers-Fletcher MV, Hanson KE. Non-culture diagnostics in fungal disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016; 30(1): 37-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.005 PMid:26897062

- Swartzentruber

S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, Zahn M, Brandt ME, Connolly P, WheatLJ.

Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin

InfectDis. 2009 Dec 15;49(12):1878-82. https://doi.org/10.1086/648421 PMid:19911965

- Scheel

CM, Samayoa B, Herrera A, Lindsley MD, Benjamin L, Reed Y, Hart J, Lima

S, Rivera BE, Raxcaco G, Chiller T, Arathoon E, Gómez BL. Development

and evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect

Histoplasma capsulatum antigenuria in immunocompromised patients. Clin

Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Jun;16(6):852-8. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00066-09 PMid:19357311 PMCid:PMC2691040

- Cloud

JL, Bauman SK, Neary BP, Ludwig KG, Ashwood ER. Performance

characteristics of a polyclonal enzyme immunoassay for the quantitation

of Histoplasma antigen in human urine samples. Am J Clin Pathol.

2007Jul;128(1):18-22. https://doi.org/10.1309/Q7879TYDW5D93QK7 PMid:17580268

- Theel

ES, Harring JA, Dababneh AS, Rollins LO, Bestrom JE, Jespersen DJ.

Reevaluation of commercial reagents for detection of Histoplasma

capsulatum antigen in urine. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 Apr;53(4):1198-203.

https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.03175-14 PMid:25631806 PMCid:PMC4365218

- Theel

ES, Jespersen DJ, Harring J, et al. Evaluation of an enzyme immunoassay

for detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen from urine specimens. J

Clin Microbiol 2013;51:3555. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01868-13 PMid:23966508 PMCid:PMC3889733

- Prattes

J, Heldt S, Eigl S, Hoenigl M. Point of care testing for the diagnosis

of fungal infections: are we there yet? Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2016;

10: 43-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-016-0254-5 PMid:27358661 PMCid:PMC4896970

- Raja

HA, Miller AN, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH Fungal Identification Using

Molecular Tools: A Primer for the Natural Products Research Community.

1 J Nat Prod. 2017 Mar 24;80(3):756-770. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01085 PMid:28199101 PMCid:PMC5368684

- Babady

NE, Buckwalter SP, Hall L, Le Febre KM, Binnicker MJ, Wengenack

NL.Detection of Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum

from culture isolates and clinical specimens by use of real-time PCR. J

Clin Microbiol. 2011Sep;49(9):3204-8. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00673-11 PMid:21752970 PMCid:PMC3165572

- Bialek

R, Cirera AC, Herrmann T, Aepinus C, Shearn-Bochsler VI, Legendre AM.

Nested PCR assays for detection of Blastomyces dermatitidis DNA

inparaffin-embedded canine tissue. J Clin Microbiol. 2003

Jan;41(1):205-8. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.1.205-208.2003 PMid:12517849 PMCid:PMC149559

- Molecular Identification of Fungi anuary 2010. Publisher: Springer ISBN: 978-3-642-05041-1

- Panel

on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections

in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of

Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases

Society of America. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed (25/07/2017)

- Johnson

PC, Wheat LJ, Cloud GA, Goldman M, Lancaster D, Bamberger DM, Powderly

WG, Hafner R, Kauffman CA, Dismukes WE; U.S. National Institute of

Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group. Safety and

efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B compared with conventional

amphotericin B for induction therapy of histoplasmosis in patients with

AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jul 16;137(2):105-9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00008 PMid:12118965

- Goldman

M, Zackin R, Fichtenbaum CJ, Skiest DJ, Koletar SL, Hafner R, Wheat LJ,

Nyangweso PM, Yiannoutsos CT, Schnizlein-Bick CT, Owens S, Aberg JA;

AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5038 Study Group. Safety of discontinuation

of maintenance therapy for disseminated histoplasmosis after

immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004

May 15;38(10):1485-9. https://doi.org/10.1086/420749 PMid:15156489

- Consolidated

Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and

Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 Jun. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/

- Focà

E, Odolini S, Sulis G, Calza S, Pietra V, Rodari P, Giorgetti PF, Noris

A, Ouedraogo P, Simpore J, Pignatelli S, Castelli F. Clinical and

immunological outcomes according to adherence to first-line HAART in a

urban and rural cohortof HIV-infected patients in Burkina Faso, West

Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Mar21;14:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-153 PMid:24656065 PMCid:PMC3994430

[TOP]

.

.