Arzouma Paul Yooda1,2,3, Serge Theophile Soubeiga1,2, K. Yacouba Nebie3, Birama Diarra1, Salam Sawadogo3, Abdoul Karim Ouattara1,2, Dorcas Obiri-Yeboah4, Albert Theophane Yonli1,2, Issoufou Tao1,2, Pegdwende Abel Sorgho1,2, Honorine Dahourou3 and Jacques Simpore1,2.

1 Laboratory

of Molecular Biology and Molecular Genetics (LABIOGENE) UFR/SVT,

University Ouaga I Prof. Joseph KI-ZERBO, 03 BP 7021 Ouagadougou

03, Burkina Faso.

2 Biomolecular Research Center Pietro Annigoni (CERBA), 01 BP 364 Ouagadougou 01, Burkina Faso.

3 National Blood Transfusion Center (CNTS), 01 BP 5372 Ouagadougou 01, Burkina Faso.

4 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, School of Medical Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana

Corresponding

author: Professor Jacques Simpore, Laboratory of Molecular Biology and

Molecular Genetics (LABIOGENE), University Ouaga I Prof. Joseph

KI-ZERBO, Burkina Faso. Tel: +226-70230792, E-mail:

jacques.simpore@labiogene.org

Published: July 1, 2018

Received: April 13, 2018

Accepted: June 12, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018041 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.041

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and Objective:

The improved performance of serological tests has significantly reduced

the risk of human immunodeficiency and hepatitis B and C viruses

transmission by blood transfusion, but there is a persistence of

residual risk. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact

of multiplex PCR in reducing the risk of residual transmission of these

viruses in seronegative blood donors in Burkina Faso.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March to September 2017.

The serological tests were performed on sera using ARCHITECTSR i1000

(Abbot diagnosis, USA). Detection of viral nucleic acids was performed

by multiplex PCR on mini-pools of seronegative plasma for HBV, HCV and

HIV using SaCycler-96 Real Time PCR v.7.3 (Sacace Biotechnologies).

Multiplex PCR-positive samples from these mini-pools were then

individually tested by the same method.

Results:

A total of 989 donors aged 17 to 65 were included in the present study.

"Repeat donors" accounted for 44.79% (443/989). Seroprevalences for

HIV, HBV, and HCV were 2.53% (25/989), 7.28% (72/989) and 2.73%

(27/989), respectively. Of the 14 co-infections detected, HBV/HCV was

the most common with 0.71% (7/989) of cases. Of 808 donations tested by

multiplex PCR, 4.70% (38/808) were positive for HBV while no donation

was positive for HIV or HCV. Conclusion:

Our study showed a high residual risk of HBV transmission through blood

transfusion. Due to the high prevalence of blood-borne infections in

Burkina Faso, we recommend the addition of multiplex PCR to serologic

tests for optimal blood donation screening.

|

Introduction

Optimal

transfusion-transmitted infections safety remains a permanent concern

in the world and especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In transfusion

practice, priority is given to the screening of three major pathogenic

viruses that are Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis B

(HBV) and C (HCV) Viruses. The highest prevalence of these viruses is

found in sub- Saharan Africa,[1,2] where 12.5% of transfused patients are at risk for post-transfusion hepatitis and 5-10% at risk of HIV infection.[1,3]

In Burkina Faso, previous studies have reported seroprevalences between

0.5%-3%, 8%-15% and 1%-9% respectively for HIV, HBV and HCV in the

general population and in blood donors.[4-9]

Today,

the risk of transmission of these viruses through transfusion has

markedly decreased due to the application of preventive measures and

improved performance of serological tests. Nevertheless, there is still

a persistence of a residual risk mainly related to the serological

window periods characterized by low-level serological viral markers,

which are usually undetectable by conventional serological assays.[10]

In order to ensure blood safety, the World Health Organization (WHO)

recommends the recruitment of voluntary, regular and unpaid donors

selected from low-risk populations.[11]

In

Burkina Faso, since its operationalization in 2005, Regional Blood

Transfusion Center of Ouagadougou (CRTS/O) has continuously improved

its blood transfusion safety policy by applying measures aimed at

reducing the residual risk of transfusion, namely: medical selected

donors, recruitment of voluntary, regular and unpaid donors and the use

of fourth-generation serological tests for the biological qualification

of blood donations.

With a view to optimal transfusion safety

research, Burkina Faso is now considering the introduction of PCR in

the screening of blood donations. The application of this technology in

blood transfusion in developed countries has made it possible to reduce

the residual transfusion risk associated with the serological window.[12-14]

Burkina Faso, a developing country (DC) has a high endemicity of these

transfusion-transmitted viral infections but has very little data on

the impact of multiplex PCR in our context. The present study was

conducted at the CRTS/O to evaluate the impact of multiplex PCR in

reducing the risk of residual transfusion-transmitted HIV,

HBV and HCV infections in blood donors seronegative for these three viruses in Burkina Faso.

Material and Methods

Type and population of study.

This was a cross-sectional study that took place from March to

September 2017 at the CRTS/O. The study population consisted of blood

donors of both genders accepted for fixed-site blood donation and

mobile collection at the CRTS/O at the end of the medical selection.

Medical screening was performed by qualified health professionals based

on a standardized pre-donation interview questionnaire designed to gain

insight on risk behaviors for HIV, HBV and HCV infections. Each donor

freely agreed to participate in the study. A "repeat donor" was any

donor who had already given at least one blood donation before this

study. Otherwise, he was considered "first- time donor".

Ethical considerations.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Ethics Committee for

Health Research of Burkina Faso (deliberation n° 2015-6-080). Written

informed consent was provided by all study participants.

Sampling.

Venous blood specimens were collected from blood donors on a red-top

and EDTA tubes. After centrifugation at 1500 g for 20 minutes, aliquots

of serum and plasma were performed within 6 hours after samples

collection for laboratory analyzes.

Screening for HIV, HBV and HCV serological markers.

The serological markers of HIV, HBV and HCV were investigated on donor

sera by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) using

ARCHITECT i1000 SR (Abbott Diagnosis, USA). The p24 antigen and

antibodies against HIV1/2 were simultaneously investigated using the

ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo Kit (Abbott, Wiesbaden Germany). HBV surface

antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV antibodies were respectively determined

using the ARCHITECT HBsAg Qualitative II (Abbott, Ireland, Sligo

Ireland) and ARCHITECT Anti-HCV (Abbott GmbH & Co.KG, Wiesbaden

Germany).

Detection for viral genomes of HIV, HBV and HCV.

The detection of viral nucleic acid was performed sequentially on the

samples obtained exclusively from blood donors who tested seronegative

for the three viruses (HIV, HBV, HCV). A first multiplex PCR was

carried out on mini-pools of 8 plasma samples each. The mini- pools

detected positive were reconstituted into 2 mini-pools of 4 plasma

samples for a second multiplex PCR. Finally, an individual PCR assay

was performed on the samples from positive mini- pools to the second

PCR.

Constitution of mini-pools.

Seronegative tested samples were divided into mini-pools of 8 plasma

samples each. Each mini-pool consisted of 160 μL of plasma from each

donation (i.e. 1.28 mL of plasma per mini-pool). Mini-pools of 8 plasma

tested positive at the first assay were reconstituted into mini-pools

of 4 plasma samples of 100 μL of each donation (i.e. 400 μL per

mini-pool).

Extraction and amplification by multiplex PCR in real time.

Molecular analysis was performed at the laboratory of Molecular Biology

and Genetics (CERBA/ LABIOGENE). Extractions of viral nucleic acid were

performed with 100 μL of mini- pool plasma using the Ribo-sorb sacaceTM

Kit (Sacace Biotechnologies®, Como Italy). PCR amplification was

performed on the SaCycler-96 Real Time PCR v.7.3 (Sacace

Biotechnologies) with the HCV/HBV/HIV Real-TM sacaceTM multiplex kit

(Sacace Biotechnologies®, Como, Italy). The PCR was carried out using a

reaction volume of 25 μL (10 μL of DNA/RNA and 15 μL of the mix). The

SaCycler-96 real-time multiplex PCR amplification was performed

according to the following program: 1 cycle of 95°C for 15 s follows by

46 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60°C for 40 s. The sensitivity of the

HCV/HBV/HIV Real-TM kit was respectively 10 IU/mL, 5 IU/mL and 20

copies/mL for HCV, HBV and HIV. After the first two amplifications,

individual real-time PCR for HBV-positive samples of the mini-pools was

performed to find the positive sample (s) from each pool. For this step

the sacaceTM Ribo-Sorb Silica kit was used for extraction and the

sacaceTM HBV Real-TM Qual kit was used for amplification according to

the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical analyzes.

The data were analyzed using the Epi Info version 7 software. The

chi-square test was used for comparisons and any value was considered

statistically significant for p ≤ 0.05.

Results

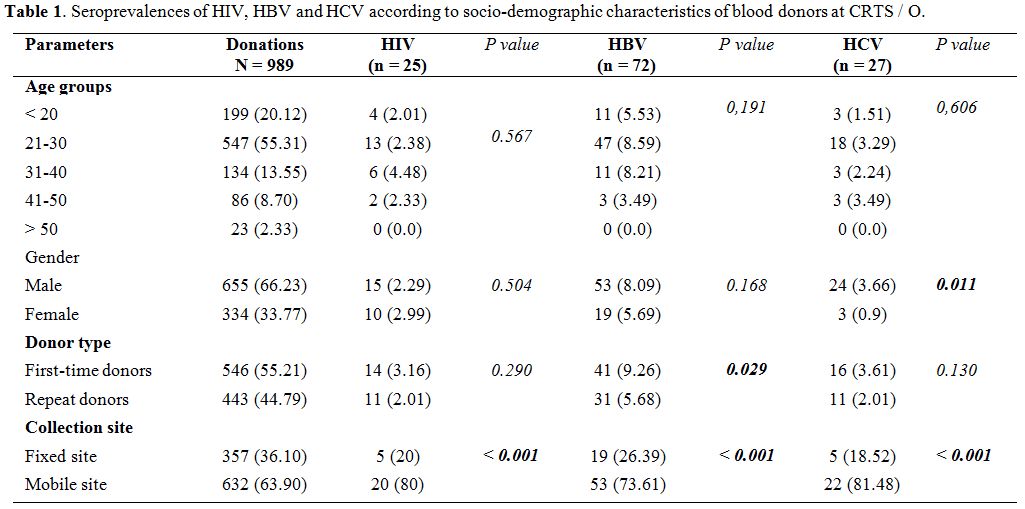

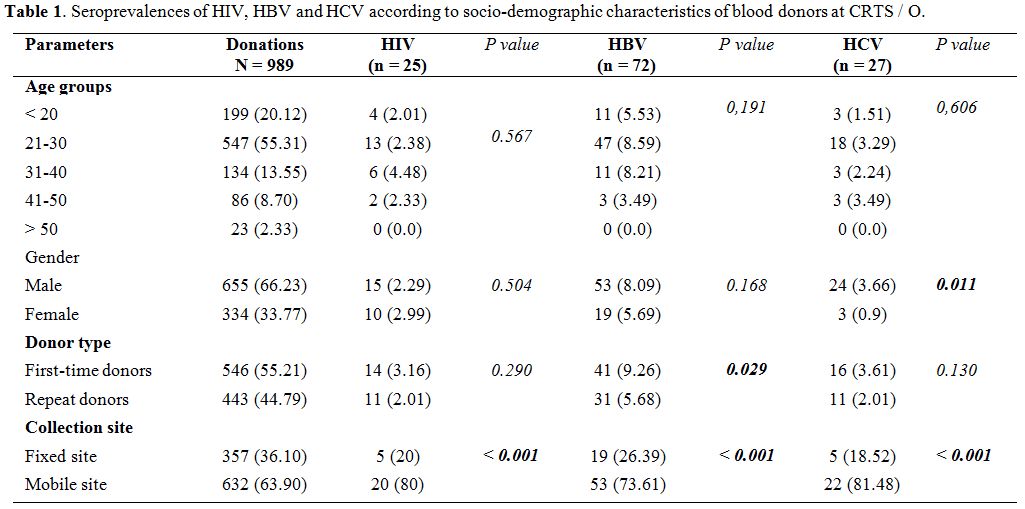

Seroprevalences

of HIV, HBV and HCV according to the socio-demographic characteristics

of blood donors at the CRTS/O. A total of 989 blood donors were

included in this study. The age of donors ranged from 17 to 65 years

with an average of 27.29 +/- 8.81 years. The 21 to 30 age group was the

most represented with 55.31% (547/989) of donors with a sex ratio (M/F)

of 1.96 in the study population. Of all blood donors, 55.21% (546/989)

were first-time donors and 66.90% (632/989) were recruited from mobile

collection sites (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Seroprevalences of HIV, HBV and HCV according to socio-demographic characteristics of blood donors at CRTS / O. |

Of

989 donations tested for antibodies and/or antigens associated with

HIV, HBV and HCV infection, 865 (87.46%) donations were detected

seronegative versus 124 (12.54%) seropositive cases. HIV infection was

positive in 2.53% (25/989) of blood donors, HBV in 7.28% (72/989) and

HCV in 2.73% (27/989) of cases. HIV/HBV,

HBV/HCV, HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV/HCV

coinfections were

0.4% (4/989), 0.71% (7/989), 0.2% (2/989) and 0.1% (1/989)

respectively. The seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible

infections was higher among first-time donors and mobile collection

sites (Table 2).

|

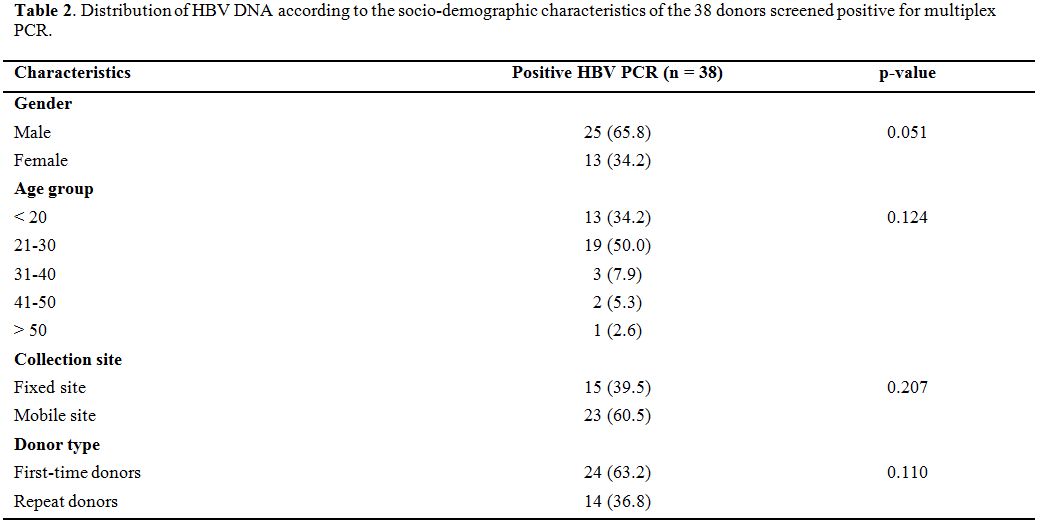

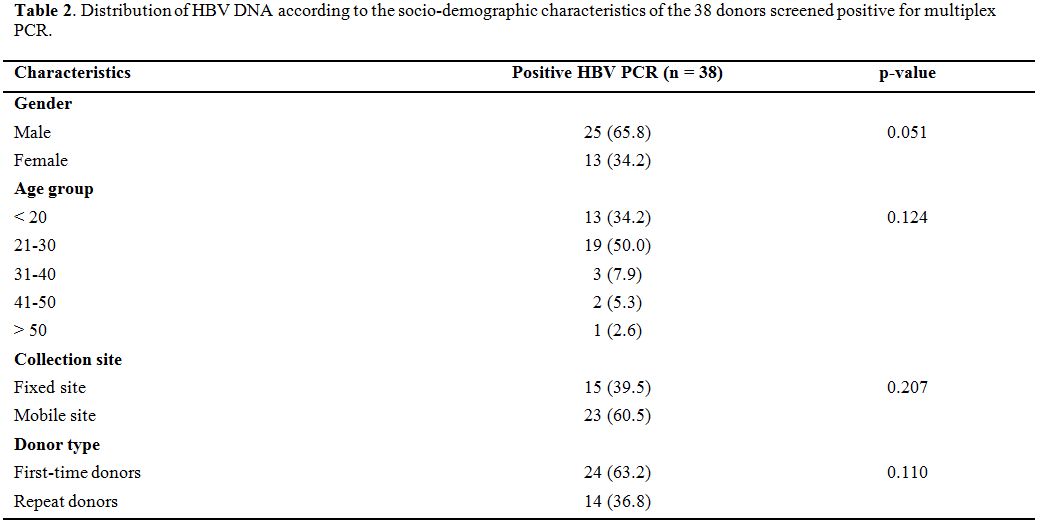

Table

2. Distribution of HBV DNA according to the socio-demographic

characteristics of the 38 donors screened positive for multiplex PCR. |

Prevalence

of HIV, HBV, and HCV genomes (DNA, RNA) in seronegative screened blood

donors by the CMIA method. Forty-three (43) mini-pools were detected

positive for HBV out of the 101 mini-pools of 8 plasma samples tested

at the first real-time multiplex PCR. No mini-pool was positive for HIV

and HCV. Of 86 mini-pools of 4 plasma samples reconstituted for the

second multiplex PCR, 42 were positive for HBV. No mini-pool was

positive for HIV and HCV. Of the 168 (42 x 4) samples tested by single

PCR, 38 were positive for HBV. Altogether, 4.70% (38/808) of

seronegative donations were positive by multiplex PCR. These positive

samples were confirmed using the same detection kit on the same device.

Discussion

The

present study which aimed to determine the impact of multiplex PCR in

reducing the residual risk of transfusion- transmitted viral

infections, reported a prevalence of 4.70% (38/808) of HBV viral DNA in

seronegative blood donors. Although the sample size is limited, this

study is the first using multiplex PCR for the seronegative-blood

donors screening in Burkina Faso.

The donations came exclusively

from voluntary and unpaid blood donors. In recent years, family or

replacement donations have been phased out by the CRTS/O in order to

comply with WHO recommendations[11] for better blood

safety. Nevertheless, our study reported seroprevalences of 2.53%,

7.28%, and 2.73% respectively for HIV, HBV, and HCV. The seroprevalence

of 2.53% of HIV reported in this study is similar to that of 2.00%

reported in the general population of the central region of Burkina

Faso in 2016[15] where our study was conducted and it

is markedly higher than the 0.8% reported in the general population of

Burkina Faso by the same study.[15] It is also higher than the 1.8% reported in blood donors from three regional centers in Burkina Faso in 2009[4] but comparable to the 2.21% reported in Koudougou blood donors in 2012.[5]

As for HBV, the prevalence of 7.28% obtained in our study was

lower than those found in previous studies in the general population9

and blood donors in Nouna,[7] Ouagadougou[9] and Koudougou[5] or in specific groups (pregnant women[7] and health workers[6]). The prevalence of 2.73% of HCV infection was also lower than the 4.4% prevalence reported among blood donors in 2014.[8]

Altogether, the results of this study show a high prevalence of HIV and

HCV against a low prevalence of HBV compared to previous studies in

Burkina Faso. This could be explained by the low rate (only 11.3%) of

regular blood donor in Burkina Faso.[4]

This

decrease in HBV prevalence can be attributed to extensive awareness and

screening campaigns during the last decade, significant improvement in

the accessibility and availability of hepatitis B vaccine and expanded

immunization program against HBV for children at 8 weeks after birth

since 2006. In addition, awareness campaigns, which are much more

focused on hepatitis B infection with free screening in recent years,

are increasingly providing a selective population of voluntary donors

at fixed sites who already know their negative serological status for

hepatitis B infection but generally unaware of their serology for HIV

and/or HCV. This could also explain the high seroprevalence of the

latter viruses and low prevalence of HBV infection compared to previous

data in Burkina Faso. Furthermore, unpublished data have shown a

variation in the prevalence of HBV infection between different

districts of Ouagadougou. This observation could be extended to HIV

and/or HCV infections. In this study, the seroprevalences of these

three viruses were higher in first-time donors than in repeat donors. A

similar observation has been made in several studies carried out in

Burkina Faso[4] and other West African countries.[16,17]

The high prevalence of these viral infections in first-time donors can

be attributed to the lower level of knowledge about blood-borne

infections and routes of transmission compared to regular or repeat

donors. However, to cope with the high demand for labile blood products

(LBP), mobile blood collections by CRTS/O is required in high schools,

universities, barracks, places of worship etc. These mobile collections

would encourage the enrollment of first-time donors although the

latter, unlike regular donors, are not always aware of the issue of

transfusion safety.[18] This increases the risk of

collection of infected donors during seroconversion period. In the

present study, 63.90% of blood donors come from mobile sites explaining

the predominance of first- time donors (55.21%).

Likewise,

the seroprevalences of these three infections were higher in the blood

donors at the mobile sites compared to those taken at the fixed site at

the CRTS/O with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001)

for all these three viral infections. This observation suggests that

our method of medical donor selection is not adapted to our blood

donors’ recruitment policy in mobile sites. Indeed, in mobile sites,

blood collections are often organized without prior awareness-raising

of potential donors on transfusion safety issues. This is especially

true as mobile collections tend to encourage the recruitment of

first-time donors. All of these results show that, despite the medical

selection of blood donors and the computerization of their data,

seroprevalences of HIV, HBV and HCV remain very high among blood donors

in Burkina Faso. This reflects shortcomings in the promotion of blood

donation and donor education prior to blood collection hence the low

proportion of regular donors. These high seroprevalences of HIV, HBV

and HCV in a population of volunteer donors also pose the problem of

the quality of medical selection. Indeed, a well-conducted medical

selection with relevant selection criteria is highly effective in

controlling the risk associated with the silent period in infections.[19-21]

In Burkina Faso, the pre-donation questionnaire and the quality of the

selection have not yet been formally evaluated. Nevertheless, a study

by Kafando et al. showed that there was no significant difference

between the positivity rate among donors accepted to donate and those

who were refused.[22]

Of 808 seronegative HIV,

HBV, and HCV donations tested by multiplex PCR, 38 (4.70%) residual

cases were detected positive. These results are higher than those

obtained in similar studies in other developing countries also

experiencing high prevalence of these three infections. For example: in

Ghana, out of 9372 seronegative screened donors by rapid tests, 3% were

detected HBV-positive DNA; no cases of HIV and HCV were detected.[23]

In South Africa,[24] the residual risk rate of HIV, HBV and HCV was estimated to be 1 per 45,765, 1 per 11, 810 and 1 per 732, 200; in Thailand,[25]

out of 4798 HIV-negative donations, 6 cases of HBV- positive cases were

detected, no HCV and HIV cases were detected. Our results are

considerably higher compared to those obtained in developed countries

where the prevalence of these three infections is low. For example:

United States[14] (HIV: 1 / 2million, HCV: 1 / 270,000), Italy[26] (HCV: 2.5 / million, HIV: 1.8 / million, HBV: 57.8 / million), Germany[27] (HCV: 1 / 10.8 million, HBV: 1/360 000). All 38 donations tested positive by multiplex PCR were only positive for HBV DNA.

These

results suggest that the residual risk of transmission of HBV by blood

transfusion is greater compared to that of HIV and HCV in Burkina Faso.

Otherwise, the contribution of PCR would be more important for HBV

compared to HIV and HCV in our country. The proportion of positive HBV

donations that are only detectable in the PCR (4.72%) obtained in our

study can be explained by the high prevalence and incidence of this

infection in the blood donor population in Burkina Faso.[4]

These high prevalences and incidences are necessarily accompanied by

significant proportions of infections in the early phase from the point

of view of serological markers. Added to this is the high prevalence of

occult hepatitis B reported in several studies in Burkina Faso.[28,29]

Occult hepatitis B is characterized by the presence of HBV

DNA in the serum of a patient who is screened for HBsAg by the usual

serological tests.[30] Although our study did not

allow us to detect residual cases associated with HIV and HCV, the

number of donations detected positive HBV by PCR confirms that PCR is

more sensitive than ELISA. This sensitivity had already

been demonstrated by some studies conducted in blood

donors in Burkina Faso,[31] and in two neighboring countries, Togo[32] and Ghana.[23]

The absence of positive cases of HIV and HCV in our study could be

explained by the relatively low prevalence of these viruses in the

general population but also the limited size of our sample. The

residual risk of HIV estimated by a mathematical model based on

serological tests was 1 for 55,000 donations among blood donors in

Burkina Faso[33] in 2011. Similarly, no cases of

residual HIV and HCV risk detectable by PCR were reported in two other

similar blood donor studies in Ghana,[23] a neighboring country in Burkina Faso and Kenya,[34]

a country of Sub-Saharan Africa like ours. However, cases of residual

risk of HIV and HCV, although relatively low compared to HBV, have been

observed in similar large-sample studies in other developing

countries and developed countries.[13,26,27]

Of

the 38 cases of HBV DNA detected in our study, 24 (63.2%) were

first-time donors versus 14 (36.8%) who were repeat donors. These

results show that the residual risk of transfusion is higher in

first-time donors compared to repeat donors, but without a significant

statistical difference. These results confirm are consistent with the

literature that donations from regular donors would be the most safety.

This is a cornerstone of WHO's strategy of promoting regular donations.

Nevertheless, we note in our study that residual cases of HBV are also

important in repeat donors. From a mathematical model, Nagalo et al.

estimated equally high incidence rates of 3270.2, 5874.1, and 6784.6

per 100,000 donations for HIV-1, HBV, and HCV, respectively, among

repeat donors.[4] Considering a 100% HBV transmission

rate by transfusion of a contaminated LBP, the PCR prevented 38 cases

of HBV transmission or even more if these 38 donations were used for

the preparation of other LBP such as Frozen Fresh Plasmas (FFPs) and

Standard Platelet Concentrates (SPC). All of these results show that in

addition to promoting unpaid and regular voluntary donation, the

implementation of the PCR is useful in the context of Burkina Faso.

Conclusion

The

study reported very high seroprevalences of HIV, HBV, and HCV in the

blood donor population in Burkina Faso. Multiplex PCR has shown

the existence of a high rate of residual cases of HBV associated with

ELISA serological tests, which is a serious concern to transfusion

safety in Burkina Faso. It is imperative for the CRTS/O to adopt a new

screening strategy for blood donations including the Screening of viral

genomes of HIV, HBV and HCV for optimal transfusion safety.

Acknowledgments

A

deep gratitude to the National Blood Transfusion Center (Burkina Faso),

the Regional Blood Center of Ouagadougou and the Biomolecular Research

Center Pietro Annigoni of Ouagadougou (CERBA).

References

- UNAIDS. Global Report on AIDS Epidemic: Treatment and care. 2008. Available at www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/jc1510_2008globalrep ort_en_0.pdf. Accessed on 09/04/2018.

- Jayaraman

S, Chalabi Z, Perel P, Guerriero C, Roberts I. The risk of

transfusion‐transmitted infections in sub‐Saharan Africa. Transfusion.

2010;50:433-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.002402.x PMid:19843290

- Fasola

F, Otegbayo I. Post-transfusion viral hepatitis in sickle cell anaemia:

retrospective-prospective analysis. Nigerian Journal of Clinical

Practice. 2002;5:16-9.

- Nagalo

BM, Bisseye C, Sanou M, Kienou K, Nebié YK, Kiba A, Dahourou H,

Ouattara S, Nikiema JB, Moret R. Seroprevalence and incidence of

transfusion‐transmitted infectious diseases among blood donors from

regional blood transfusion centres in Burkina Faso, West Africa.

Tropical medicine & international health. 2012;17:247- 53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02902.x PMid:21988100

- Nagalo

MB, Sanou M, Bisseye C, Kaboré MI, Nebie YK, Kienou K, Kiba A, Dahourou

H, Ouattara S, Zongo JD. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency

virus, hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis among blood donors in

Koudougou (Burkina Faso) in 2009. Blood transfusion. 2011;9:419.

PMid:21839011 PMCid:PMC3200412

- Pietra

V, Kiema D, Sorgho D, Kabore S, Mande S, Castelli F, Puoti M, Simpore

J. Prévalence des marqueurs du virus de l'hépatite B et des anticorps

contre le virus de l'hépatite C parmi le personnel du District

Sanitaire de Nanoro, Burkina Faso. Science et technique, sciences de la

santé. 2008;31:53-9.

- Collenberg

E, Ouedraogo T, Ganamé J, Fickenscher H, Kynast‐Wolf G, Becher H,

Kouyaté B, Kräusslich HG, Sangaré L, Tebit DM. Seroprevalence of six

different viruses among pregnant women and blood donors in rural and

urban Burkina Faso: a comparative analysis. Journal of medical

virology. 2006;78:683-92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.20593 PMid:16555290

- Zeba

MTA, Sanou M, Bisseye C, Kiba A, Nagalo BM, Djigma FW, Compaoré TR,

Nebié YK, Kienou K, Sagna T. Characterisation of hepatitis C virus

genotype among blood donors at the regional blood transfusion centre of

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Blood Transfusion. 2014;12:s54.

PMid:24599906 PMCid:PMC3934227

- Tao

I, Compaoré TR, Diarra B, Djigma F, Zohoncon TM, Assih M, Ouermi D,

Pietra V, Karou SD, Simpore J. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B and C

viruses in the general population of burkina faso. Hepatitis research

and treatment. 2014;2014.

- Kleinman

S, Busch MP, Korelitz JJ, Schreiber GB. The incidence/window period

model and its use to assess the risk of transfusion-transmitted human

immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Transfusion

medicine reviews. 1997;11:155-72. https://doi.org/10.1053/tmrv.1997.0110155 PMid:9243769

- WHO. Blood safety: A strategy for the AFRICAN REGION. 2001. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/95734/AFR_RC51_R2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed on 09/04/2018.

- Davidson

T, Ekermo B, Gaines H, Lesko B, Åkerlind B. The cost‐ effectiveness of

introducing nucleic acid testing to test for hepatitis B, hepatitis C,

and human immunodeficiency virus among blood donors in Sweden.

Transfusion. 2011;51:421-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02877.x PMid:20849409

- Stramer

S, Glynn S, Kleinman S. Detection of Hiv-1 and Hcv infections among

antibody-negative blood donors by nucleic acid amplification testing.

Vox Sanguinis. 2005;88:68-9.

- Zou

S, Dorsey KA, Notari EP, Foster GA, Krysztof DE, Musavi F, Dodd RY,

Stramer SL. Prevalence, incidence, and residual risk of human

immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections among United

States blood donors since the introduction of nucleic acid testing.

Transfusion. 2010;50:1495-504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02622.x PMid:20345570

- CNLS/IST. Rapport d'activité sur la riposte au SIDA au Burkina Faso. http://www.unaidsorg/sites/default/files/country//BFA_narrative_repo rt_2016pdf. 2016. Accessed on 09/04/2018.

- Mavenyengwa

RT, Mukesi M, Chipare I, Shoombe E. Prevalence of human

immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, hepatitis B and C in blood donations

in Namibia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:424. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-424 PMid:24884633 PMCid:PMC4012713

- Noubiap

JJN, Joko WYA, Nansseu JRN, Tene UG, Siaka C. Sero- epidemiology of

human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis

infections among first-time blood donors in Edéa, Cameroon.

International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17:e832-e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2012.12.007 PMid:23317526

- Nébié

K, Olinger C, Kafando E, Dahourou H, Diallo S, Kientega Y, Domo Y,

Kienou K, Ouattara S, Sawadogo I. Faible niveau de connaissances des

donneurs de sang au Burkina Faso; une entrave potentielle à la sécurité

transfusionnelle. Transfusion clinique et biologique. 2007;14:446-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2007.12.005 PMid:18295528

- Stokx

J, Gillet P, De Weggheleire A, Casas EC, Maendaenda R, Beulane AJ, Jani

IV, Kidane S, Mosse CD, Jacobs J. Seroprevalence of

transfusion-transmissible infections and evaluation of the pre-

donation screening performance at the Provincial Hospital of Tete,

Mozambique. BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-141 PMid:21605363 PMCid:PMC3120673

- Seck

M, Dieye B, Guèye Y, Faye B, Senghor A, Toure S, Dieng N, Sall A, Touré

A, Dièye T. Évaluation de l'efficacité de la sélection médicale des

donneurs de sang dans la prévention des agents infectieux. Transfusion

Clinique et Biologique. 2016;23:98-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2015.11.001 PMid:26681660

- Tagny

CT, Kouao MD, Touré H, Gargouri J, Fazul AS, Ouattara S, Anani L,

Othmani H, Feteke L, Dahourou H. Transfusion safety in francophone

African countries: an analysis of strategies for the medical selection

of blood donors. Transfusion. 2012;52:134-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03391.x PMid:22014098 PMCid:PMC3668689

- Kafando

E, Nébié Y, S S, Kienou K, Dahourou H, Simpore J. Risk Behavior among

Ineligible Blood Donors in a Blood Transfusion Center (Burkina Faso). J

Hematol Blood Transfus Disord. 2017;4:015.

- Owusu‐Ofori

S, Temple J, Sarkodie F, Anokwa

M, Candotti D, Allain JP. Predonation screening of blood

donors with rapid tests: implementation and efficacy of a novel

approach to blood safety in resource‐poor settings. Transfusion.

2005;45:133-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04279.x PMid:15660820

- Vermeulen

M, Lelie N, Sykes W, Crookes R, Swanevelder J, Gaggia L, Le Roux M,

Kuun E, Gulube S, Reddy R. Impact of individual‐ donation nucleic acid

testing on risk of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and

hepatitis C virus transmission by blood transfusion in South Africa.

Transfusion. 2009;49:1115-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02110.x PMid:19309474

- Nantachit

N, Thaikruea L, Thongsawat S, Leetrakool N, Fongsatikul L, Sompan P,

Fong YL, Nichols D, Ziermann R, Ness P. Evaluation of a multiplex

human immunodeficiency virus‐1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B

virus nucleic acid testing assay to detect viremic blood donors in

northern Thailand. Transfusion. 2007;47:1803-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01395.x PMid:17880604

- Velati

C, Romanò L, Fomiatti L, Baruffi L, Zanetti AR. Impact of nucleic acid

testing for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human

immunodeficiency virus on the safety of blood supply in Italy: a 6‐

year survey. Transfusion. 2008;48:2205-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01813.x PMid:18631163

- Hourfar

MK, Jork C, Schottstedt V,

Weber‐Schehl M, Brixner V, Busch MP, Geusendam G,

Gubbe K, Mahnhardt C, Mayr‐Wohlfart U. Experience of German Red Cross

blood donor services with nucleic acid testing: results of screening

more than 30 million blood donations for human

immunodeficiency virus‐1, hepatitis C virus,

and hepatitis B virus. Transfusion. 2008;48:1558-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01718.x PMid:18466173

- Somda

K, Sermé A, Coulibaly A, Cissé K, Sawadogo A, Sombié A, Bougouma A.

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Should Not Be the Only Sought Marker to

Distinguish Blood Donors towards Hepatitis B Virus Infection in High

Prevalence Area. Open Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;6:362. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojgas.2016.611039

- Diarra

B, Yonli AT, Sorgho PA, Compaore TR, Ouattara AK, Zongo WA, Tao I,

Traore L, Soubeiga ST, Djigma FW. Occult hepatitis B virus infection

and associated genotypes among HBsAg-negative subjects in Burkina Faso.

Mediterranean journal of hematology and infectious diseases. 2018;10. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2018.007

- Raimondo

G, Allain J-P, Brunetto MR, Buendia M-A, Chen D-S, Colombo M, Craxì A,

Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB. Statements from the Taormina expert

meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of hepatology.

2008;49:652-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.014 PMid:18715666

- Nagalo

B, Bisseye C, Sanou M, Nebié Y, Kiba A, Kienou K, Zongo J, Simporé J.

Diagnostic moléculaire du virus de l'immunodéficience humaine acquise

(VIH) sur les pools de plasmas de donneurs de sang au centre régional

de transfusion sanguine de Ouagadougou (CRST- 0), Burkina Faso.

Médecine tropicale. 2011;71:137-41.

- Assih

M, Feteke L, Bisseye C, Ouermi D, Djigma F, Karou SD, Simpore J.

Molecular diagnosis of the human immunodeficiency, hepatitis B and C

viruses among blood donors in lomé (Togo) by multiplex real time PCR.

The Pan African Medical Journal. 2016;25. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.25.242.7096

- Lefrère

JJ, Dahourouh H, Dokekias AE, Kouao MD, Diarra A, Diop S, Tapko JB,

Murphy EL, Laperche S, Pillonel J. Estimate of the residual

risk of transfusion‐transmitted human

immunodeficiency virus infection in sub‐Saharan Africa: a multinational

collaborative study. Transfusion. 2011;51:486-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537- 2995.2010.02886.x PMid:20880002

- Basavaraju

S, Mwangi J, Nyamongo J, Zeh C, Kimani D, Shiraishi R, Madoda R, Okonji

J, Sugut W, Ongwae S. Reduced risk of

transfusion‐transmitted HIV in

Kenya through centrally co‐

ordinated blood centres, stringent donor selection and effective p24

antigen‐HIV antibody screening. Vox sanguinis. 2010;99:212-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01340.x PMid:20497410

[TOP]