Ferhat Arslan1, Sehnaz Alp2, Yahya Büyükasık3, Melda Comert Ozkan4, Fahri Şahin4, Seniha Basaran5, Arif Atahan Cagatay5, Ömer Haluk Eraksoy5, Kenan Aksu6, Barış Ertunç7, Volkan Korten8, Bahadır Ceylan9 and Ali Mert9.

1 Department

of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine,

Istanbul Medeniyet University, Istanbul, Turkey.

2 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

3 Department of Hematology, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

4 Department of Hematology, Faculty of Medicine, Ege University, İzmir, Turkey.

5 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey.

6 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, Ege University, İzmir, Turkey.

7

Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of

Medicine, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey.

8 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey.

9

Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of

Medicine, Istanbul Medipol University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Correspondence to: Ferhat Arslan, MD. Department of Infectious Diseases

and Clinical Microbiology, İstanbul Medeniyet University Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey. Tel.: +90 505 580 22 45. E-mail:

ferhatarslandr@hotmail.com

Published: September 1, 2018

Received: February 22, 2018

Accepted: July 11, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018047 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.047

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Hemophagocytic

Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an indicator of an exaggerated immune

response and eventually adverse outcomes. This study aimed to

investigate the clinical and laboratory features and outcomes of

patients with HLH. The medical records of 26 HLH adult patients (≥ 16

years of age) were retrospectively analyzed. Gender, age, the duration

of fever, time to diagnosis, etiology and laboratory data were

extracted from the records. The mean age was 38 ± 18 years, and 15

(58%) patients were female. A total of nine cases had infectious

diseases; four cases had rheumatologic diseases, three cases had

hematological malignancies while nine cases could not have a definitive

diagnosis. The median time to detection of HLH was 20 days (IQR: 8-30

d). Of the 25 patients, 11 (44%) died. The erythrocyte sedimentation

rates of the surviving and non-surviving patients were 39 ± 22 mm/h and

15 ± 13 mm/h, respectively. When a long-lasting fever is complicated by

bicytopenia or pancytopenia (especially), clinicians should promptly

consider the possibility of HLH syndrome to improve patients’

prognosis.

|

Introduction

Hemophagocytic

Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening clinical condition

caused by an exaggerated immune response that results in tissue

destruction.[1] Its primary form generally occurs due

to an underlying genetic immune dysfunction and primarily affects

infants and young children, whereas the secondary form occurs due to

various underlying conditions ranging from viral infections to

autoimmune diseases and cancers in adults.[2,3]

The

clinical features of HLH include fever, hepatosplenomegaly,

lymphadenopathy, neurological symptoms, and skin manifestations.

Cytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, high serum ferritin levels,

hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia are laboratory

abnormalities that have frequently been reported in HLH patients.[4]

Although extremely elevated ferritin levels represent a highly

sensitive marker of HLH, this disease may be difficult to recognize and

diagnose.[5] Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of

the underlying cause are important to decrease morbidity and mortality

in patients with HLH.[6] In this study, we aimed to

investigate the clinical features and outcomes of patients with HLH in

tertiary care centers in Turkey through a retrospective chart review.

Materials and Methods

The

medical records of adult patients (≥ 16 years of age) diagnosed with

HLH between January 2010 and April 2016 at six university hospitals in

Turkey were reviewed retrospectively.

Infectious disease,

rheumatology, and hematology specialists were contacted for the

records. The Istanbul Medipol University Ethical Committee approved

this study.

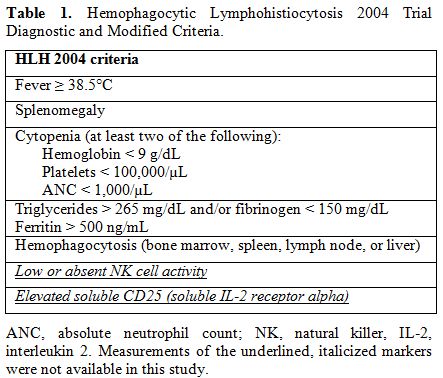

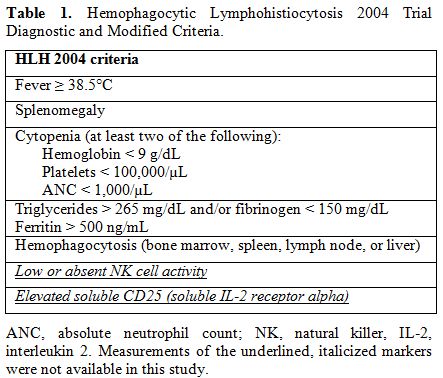

All the patients who met the diagnostic guidelines of the Histiocyte Society (HLH-2004) were included in this study (Table 1).[7]

Molecular parameters, such as NK cell activity and soluble CD25, were

not available in this study due to a lack of laboratory facilities. The

following features were evaluated: fever (type, duration), time to

diagnosis, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, rash, serosal

involvement, respiratory symptoms, neurological symptoms, and

opportunistic infections. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were defined as

the long axis of the organs exceeding 155 mm and 130 mm on radiological

investigations, respectively.[8]

|

Table 1. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis 2004 Trial Diagnostic and Modified Criteria. |

Hemogram, ferritin,

lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), transaminase, bilirubin, triglyceride,

high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and fibrinogen levels and erythrocyte

sedimentation rates (ESRs) were analyzed. Hemophagocytosis was defined

as histological evidence of activated macrophages engulfing blood cells

in the bone marrow and/or other tissues.

Opportunistic infections

were defined as a new clinical condition with ongoing immunosuppression

due to HLH. When positron emission tomography with computed tomography

(PET/CT) was performed, the presence of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake

was evaluated. Underlying triggering diseases and treatment modalities,

including types of initial therapy, secondary therapy, and adjunctive

therapy (supportive or underlying disease-specific treatment), were

evaluated. Patients without both ferritin and triglyceride levels in

their medical records were excluded.

The basic statistical

analysis was performed using R version 3.0.4. Results are expressed as

numbers (percentages) for categoric variable and as mean (standard

deviation) or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables.

The chi-square test and contingency table were used to compare

subgroups of patients. p values of less than 0.05 were considered as

statistically significant.

Results

26

patients met the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the patients was

38 years (range, 16-74), and 15 (58%) females were included. The

triggering etiologies were established in 17 cases (65%) and were as

follows: infection in 9 cases (Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever [CCHF]

in 1 case, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV] in 4 case, cytomegalovirus [CMV] in

1 case, influenza virus in 1 case, toxoplasmosis in 1 case, and

histoplasmosis in 1 case), rheumatologic disease in 3 cases

(adult-onset Still’s disease [AOSD] in 1 cases, rheumatoid arthritis in

1 case, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE] in 1 case), hematologic

malignancy in 3 cases (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 2 cases,

intravascular lymphoma in 1 case), and ulcerative colitis in 1 case. Of

the 26 patients, 11 (42%) died. Of the fatal cases, five had an

infectious etiology, one lymphoma, and the other five were associated

with an unknown etiology.

Fever was the most common sign among

the HLH patients. It was the primary presenting symptom in all cases.

The median duration of fever was 19 days (IQR, 10-30), and the median

time to diagnosis was 21 days (IQR 8-30). Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly

were detected in 21 (84%), and 23 (92%) patients, respectively, and 18

(72%) patients had lymphadenopathies (peripheral in 2 patients and

systemic in 16 patients).

Neurological manifestations, including

encephalopathy, seizures, and an altered level of consciousness, were

observed in nine cases (38%). Bilaterally thalamic involvement and

demyelinization findings were revealed in two different patients who

had not apparent neurological symptoms. In two patients, the

neurological findings were associated with herpes simplex virus (HSV)

reactivation. HSV DNA was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and

blood of two patients with encephalitis. Eight patients who received

immunosuppressive drugs for HLH developed concomitant opportunistic

infections (CMV in three patients, HSV in three patients, invasive

aspergillosis in one patient, and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in one patient).

The

erythrocyte sedimentation rates of the surviving and non-surviving

patients were 39 ± 22 mm/h and 16 ± 14 mm/h, respectively. The median

ferritin level was 8826 ng/ml (IQR 1656-27386 ng/ml, range 566-100000

ng/ml), the median LDH level was 1562 IU/ml (range; 342-5251 IU/ml) and

total bilirubin level median was 1.85 mg/dl (IQR 0.8-6.1 mg/dl). The

mean triglyceride level was 528±321 mg/dl, and the median HDL levels

were 7 mg/dl (IQR 5-12 mg/dl).

Bone marrow biopsy showed

hemophagocytosis in 22 of 26 (84%) patients. Additionally, there was

bone marrow involvement in two of the lymphoma cases. Activated

macrophages with maturation arrest (in 2 patients) and chronic

lymphoproliferation were the other findings in bone marrow biopsies.

Hemophagocytosis and hemosiderosis were observed in liver biopsies of

two of these patients.

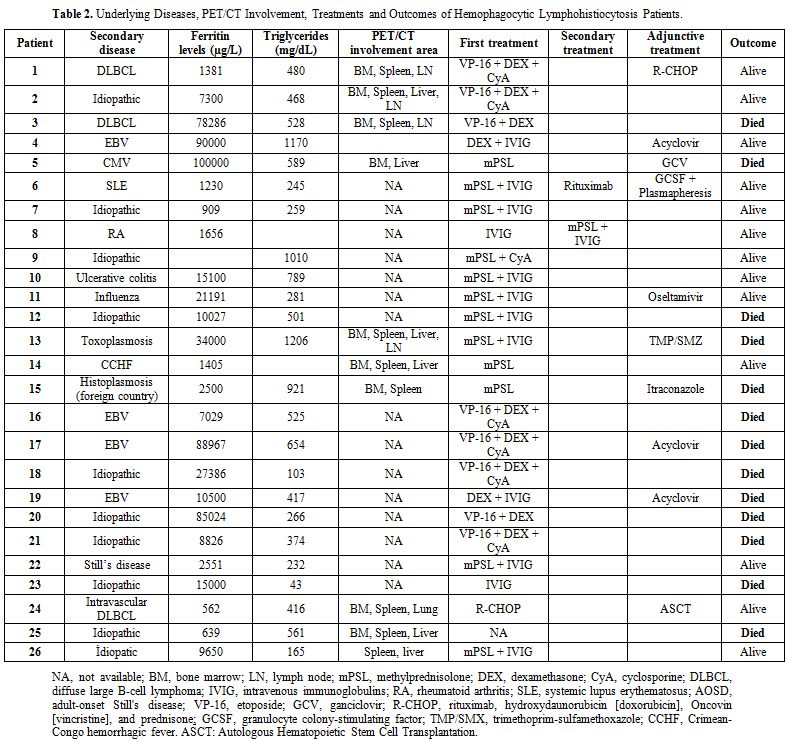

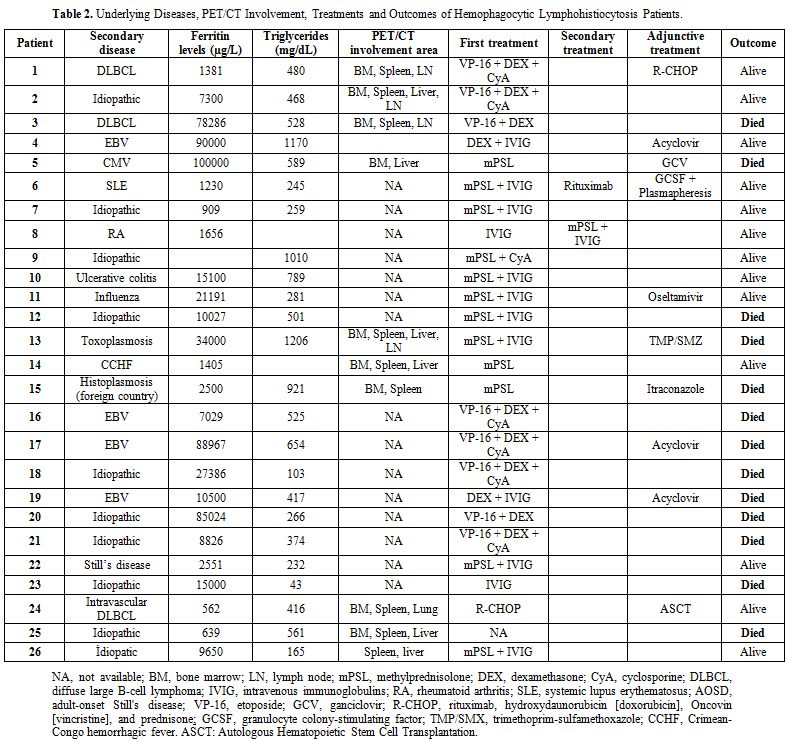

Of the 26 patients, eight were evaluated by PET/CT scans; their findings are summarized in Table 2.

All

the patients with HLH received specific treatment for the

hemophagocytic syndrome. Three patients (12%) were treated only with

glucocorticoids, whereas the others received both glucocorticoids and

another drug(s) as initial treatment. The underlying diseases,

HLH-associated laboratory values and initial, secondary, and adjunctive

treatment modalities of the patients after HLH diagnosis are summarized

in Table 2.

|

Table

2. Underlying Diseases, PET/CT Involvement, Treatments and Outcomes of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Patients. |

Discussion

Various underlying conditions that predispose patients to HLH have been defined in previous studies.[9,10,11] In children, underlying genetic defects play a predominant part in the development of HLH.[11,12] Although malignancies, frequently hematologic, seem to be the leading cause of adult-onset HLH,[11]

the predominant cause of HLH may differ by country because of different

genetic/ethnic backgrounds or differences in triggering agents,

particularly infections.[11,12] However, only 3 of 26

patients in our study were diagnosed with lymphoma. Although, this

finding may reflect the underrepresentation of hematology units at

participating centers or underdiagnosed lymphoproliferative diseases, a

similar distribution of causes of this disease in the Mediterranean

Region has been found in Spain but not in Italy and in France.[11]

Many

clinical and laboratory features were consistent with those reported

previously, e.g., high fever, cytopenia, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly,

and hyperferritinemia.[4] Fever was the primary presenting symptom in all of our patients, which is similar to a report from Riviere et al.[4]

Hyperferritinemia is a sensitive marker of HLH. No cutoff value has

been defined as critical; however, high levels of ferritin (> 50,000

µg/L) are associated with a poor prognosis.[13]

Hypofibrinogenemia is the main factor for blood cells velocity that

also stated as bad prognostic factor for HLH. Riviere et al. found

higher LDH levels in patients with hemophagocytic syndrome (positive

cases) than in negative and undetermined patients.[4]

In

our case series, the baseline ESR values, the median ferritin, LDH and

total bilirubin levels of the non-survivors were higher than those of

the survivors. But, due to limited numbers of patients to conclude

statistical significance with parametric and non-parametric tests, we

do not give any hypothetical test results here. We may say that more

tissue destruction like liver as cholestatic hepatitis and blood cells

hemolysis can explain the higher LDH and total bilirubin levels in

non-survivors as bad prognostic factors.

Neurological symptoms

may manifest as different clinical presentations, ranging from

depression and convulsions to progressive encephalopathy. In one study,

HSV reactivation was not found in patients with hemophagocytosis and

multi-organ failure.[14] In contrast, two of the five cases with neurological findings in our study involved HSV reactivation.

Hemophagocytosis

has been demonstrated in HLH patients, especially in the bone marrow,

spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. It is a diagnostic criterion.

Hemophagocytosis was reported in bone marrow aspirates in 84% of HLH

cases of the literature, which is similar to our findings.

Hemophagocytosis by itself is not a pathognomonic finding for the

diagnosis of HLH.[15] Because hemophagocytosis may be

a late finding in progressive HLH, repeat biopsies may be needed to

confirm the diagnosis in some cases.[1]

PET/CT is

a recently developed technique that is especially useful in cases of

malignancy, and this method may be valuable for diagnosing underlying

malignancies versus isolated HLH. In several reported cases, the

diffuse involvement of the bone marrow associated with spleen, liver,

and lymph node involvement has been found on PET/CT scans, which is

consistent with hemophagocytosis.[16] Little

information is available regarding whether PET/CT findings were related

to underlying or opportunistic diseases versus HLH. The underlying

conditions of our patients may have been responsible for the PET/CT

findings; however, one idiopathic case showed a diffuse involvement of

the reticuloendothelial system, which was considered to be associated

with HLH (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. (Maximum

intensity projection) The anterior view of a patient showing diffuse

F18-FDG uptake of the liver with a SUVmaxvalue of 4.5 (normal:

3.2±0.8) and an increase in liver dimensions. |

In 2004, a new HLH treatment protocol was published (HLH-2004).[7]

Corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and etoposide constitute the backbone of

treatment. Among our cases, only two patients were treated with this

backbone therapy, and they recovered completely with good prognoses.

Etoposide-based steroid combination regimens have been confirmed to

improve HLH-associated outcomes in most trials.[17]

All

the patients had been treated with at least one antibiotic regimen

preceding the diagnosis of suspected sepsis (data not presented). Of

the 25 patients, 3 received only high-dose corticosteroids as initial

management, and only 1 case (a CCHF patient) resolved clinically. All

the patients with rheumatologic disease-related HLH responded to

treatment with good prognoses. While etoposide and cyclosporine

combination with high dose corticosteroid is the recommended regime for

HLH, in our study, eight patients were treated with etoposide

containing regimes, and six of them died. Mortality in rheumatological

diseases is significantly lower than that in infection- or

malignancy-related HLH.[18]

The reported

mortality of secondary HLH in adult case series varies from 20-74.8%,

which is similar to the rate of 44% in our case series.[4,11] Our cases with underlying rheumatological diseases also showed a good prognosis.

Advanced

age, the presence of lymphoma or infectious disease, transplantation,

and persistent fever within three days after the first treatment have

been clinically defined as poor prognostic factors.[4]

Although a statistical comparison was not possible, ten of the fatal

cases in this study had an infectious (~50%) and idiopathic (~50%)

etiology.

This retrospective case series study was intended to

present an additional adult HLH case series to the literature. Its

retrospective nature and small sample size are important limitations.

In conclusion, HLH occurs secondary to many diseases observed in

internal medicine practice. When a long-lasting fever is complicated by

bicytopenia or pancytopenia (especially), clinicians must promptly

consider the possibility of HLH syndrome since early diagnosis improves

patients’ prognosis. Especially low ESR levels and infectious or

idiopathic etiology may be alarmed conditions for unfavorable outcome

in the management of HLH.

References

- Rosado FGN, Kim AS: Hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis: an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin

Pathol 2013; 139:713–727 https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCP4ZDKJ4ICOUAT PMid:23690113

- Basheer

A, Padhi S, Boopathy V, Mallick S, Nair S, Varghese RG, Kanungo R.

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: an Unusual Complication of Orientia

tsutsugamushi Disease (Scrub Typhus). Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2015 ;7(1):e2015008. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2015.008. eCollection 2015.

- Hayden

A, Park S, Giustini D, et al.: Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs)

including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults: A

systematic scoping review. Blood Rev 2016; 30:411–420 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2016.05.001 PMid:27238576

- Rivière

S, Galicier L, Coppo P, et al.: Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in

adults: A multicenter retrospective analysis of 162 patients. Am J Med

2014 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.034 PMid:24835040

- Wormsbecker

AJ, Sweet DD, Mann SL, et al.: Conditions associated with extreme

hyperferritinemia (>3000 μg/L) in adults. Intern Med J 2015;

45:828–833 https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12768 PMid:25851400

- Trottestam

H, Horne A, Aricò M, et al.: Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment

protocol. Blood 2011; 118:4577–4584 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-06-356261 PMid:21900192 PMCid:PMC3208276

- Henter

J-I, Horne A, Aricó M, et al.: HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic

guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer

2007; 48:124–131 https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21039 PMid:16937360

- Dick R, Watkinson A: The liver and spleen. Textb Radiol Imaging 2002; 981–1028

- Song

Y, Pei R-J, Wang Y-N, et al.: Central Nervous System Involvement in

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Adults: A Retrospective Analysis

of 96 Patients in a Single Center. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018; 131:776–783 https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.228234 PMid:29578120 PMCid:PMC5887735

- Lorenz

F, Klimkowska M, Pawłowicz E, et al.: Clinical characteristics, therapy

response, and outcome of 51 adult patients with hematological

malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a single

institution experience. Leuk Lymphoma 2018; 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2017.1403018

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al.: Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014; 383:1503–1516 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X

- Ozen

S, Dai A, Coskun E, Oztuzcu S, Ergun S, Aktekin E, Yavuz S, Bay

A.Importance of hyperbilirubinemia in differentiation of primary and

secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric cases.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6 :e2014067. doi:

10.4084/MJHID.2014.067. eCollection 2014 https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2014.067

- Sackett

K, Cunderlik M, Sahni N, et al.: Extreme Hyperferritinemia: Causes and

Impact on Diagnostic Reasoning. Am J Clin Pathol 2016; 145:646–650 https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqw053 PMid:27247369

- François

B, Trimoreau F, Desachy A, et al.: [Hemophagocytosis during multiple

organ failure: M-CSF overproduction or viral reactivation?]. Ann Fr

Anesthèsie Rèanimation 2001; 20:514–519 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0750-7658(01)00410-5

- Ho

C, Yao X, Tian L, et al.: Marrow assessment for hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis demonstrates poor correlation with disease

probability. Am J Clin Pathol 2014; 141:62–71 https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPMD5TJEFOOVBW PMid:24343738

- Kim

J, Yoo SW, Kang S-R, et al.: Clinical implication of F-18 FDG PET/CT in

patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Ann Hematol

2014; 93:661–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1906-y PMid:24061788

- Bergsten

E, Horne A, Aricó M, et al.: Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and

dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative

HLH-2004 study. Blood 2017; 130:2728–2738 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-06-788349 PMid:28935695 PMCid:PMC5785801

- Ishii

E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al.: Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol 2007; 86:58–65 https://doi.org/10.1532/IJH97.07012 PMid:17675268

[TOP]