Elmoubasher Farag1*, Devendra Bansal2, Mohamad Abdul Halim Chehab3, Ayman Al-Dahshan3, Mohamed Bala3, Nandakumar Ganesan1, Yosuf Abdulla Al Abdulla4, Mohammed Al Thani1, Ali A. Sultan2 and Hamad Al-Romaihi1.

1 Ministry of Public Health, Doha, Qatar.

2 Department Microbiology and Immunology, Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, Cornell University, Doha, Qatar.

3 Community medicine residency program, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

4 Consultant physician, Primary Health Care Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

Correspondence to: Elmoubasher Farag. Ministry of Public Health, Doha, Qatar. E-mail:

eabdfarag@moph.gov.qa

Published: September 1, 2018

Received: May 4, 2018

Accepted: August 3, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018050 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.050

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background

and Objectives. Imported malaria poses a serious public health problem

in Qatar because its population is “naïve” to such infection; where

local transmission might lead to serious, life-threatening infection

and might even trigger epidemics.

Methods. This study is a

retrospective review of the imported malaria cases in Qatar reported by

the malaria surveillance program at the Ministry of Public Health

(MoPH), during the period between January 2008 and December 2015. All

cases were imported and underwent parasitological confirmation through

microscopy.

Results. A total of 4092 malaria cases were reported

during 2008-2015 in Qatar. The demographic features of the imported

cases show that the majority of cases were males (93%), non-Qatari

(99.6%), and aged 15 to 44 years (82.1%). Moreover, P. vivax was found

to be the main etiologic agent accounting for more than three-quarters

(78.7%) of the imported cases. In addition, almost a third (33.1%) of

the cases were reported during the months of July, August, and

September.

Conclusions. Imported malaria in Qatar has witnessed an

increase during the past seven years, despite a long period of constant

reduction; where the people most affected were adult male migrants from

endemic countries. Many challenges need to be overcome to prevent the

reintroduction of malaria into the country.

|

Introduction

The

global importance of malaria is immense. It is the most prevalent

vector-borne disease in the world, threatening some 2-3 billion people

in more than 90 countries - 56% of the world's population. In 2016, the

World Health Organization estimated that there were 216 million malaria

cases and 445 000 deaths attributable to malaria.[1]

Most of these deaths occurred in the African region (91%), followed by

the South-East Asian region (7%) and the Eastern Mediterranean region

(2%).[2] The vast majority of deaths occurred among

young children; other high-risk groups included pregnant women,

non-immune travelers, refugees, displaced persons, and laborers

entering endemic areas.[3] It is a well-known fact

that both tourists and visiting friends and relatives (VFR) are at high

risk of malaria as they are less likely to use chemoprophylaxis.[4,5]

Moreover, those VFR are at an increased risk of travel-related

diseases, have lower risk perception and awareness, don’t seek

pre-travel advice, and are more likely to reside in remote rural areas

when compared with tourists to the same destinations.[5]

Qatar

is a country (population 2,235,355 in 2015) located in the west of the

Arabian Peninsula. Even though indigenous malaria transmission has been

eliminated in the1970s, the risk of imported malaria still exists due

to the massive influx of migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent

and Sub-Saharan Africa.[6,7] Moreover, this influx has recorded a 9-fold increase between 1995 and 2014.[8]

Additionally, the potential of malaria reintroduction in the country

exists due to the presence of two malaria vectors, namely: A. stephensi and A. multicolor.

The incidence of malaria was found to be in a consistent decline from

1997 to reach the lowest rate in 2004 but then increased by more than

two times in 2005 and 2006.[7] In 2008, approximately 200-250 cases of imported malaria were reported, and P. vivax

was the main etiologic agent. Furthermore, all the patients had a

travel history to malaria-endemic countries as India, Pakistan, and

Sudan.[9] Consequently, imported malaria poses a

serious public health problem in Qatar because the population is

“naïve” to such infection; where local transmission might lead to

serious, life-threatening infection and could even trigger epidemics.

Currently,

information regarding malaria surveillance in Qatar is insufficient to

provide a clear epidemiological picture necessary for the development

of a national strategy to control malaria importation. Therefore, the

country is at risk of such disease and requires robust surveillance and

preparedness to address any potential outbreaks. Thus, in the present

retrospective study, we build a record of data regarding the incidence

of malaria in Qatar to stall the potential spread of this deadly

infection in Qatar.

Materials and Methods

This

study is a retrospective review of the imported malaria cases in Qatar

reported by the malaria surveillance program at the Ministry of Public

Health (MoPH), during the period between January 2008 and December

2015. Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) is the main health care facility

catering for the population of Qatar and epidemiologically represents

both locals and expatriates in the country; where the hematological

laboratory at HMC is considered to be the national reference

laboratory. All the malaria cases in the present study were reported

from the highly specialized hospitals of HMC: Hamad General Hospital,

Al-Wakrah Hospital, and Al-Khor Hospital. Other sources of malaria

cases were Qatar’s primary health care provider, Primary Health Care

Corporation (PHCC), through its 23 centers as well as the hospitals and

health centers of the private sector.

Malaria Case Management.

In Qatar, the management of malaria cases is centralized under HMC, the

main and government-based provider of secondary and tertiary care in

the country. Malaria cases are typically seen in the emergency

department and triaged accordingly as uncomplicated or complicated

cases based on specific case definitions. Patients infected with P. falciparum / P. vivax having different clinical status are generally defined according to the World Health Organization guidelines.[1]

Moreover, malaria cases are designated as severe (complicated) cases

depending on certain laboratory (e.g. parasitemia > 5%, severe

normocytic anemia of Hb < 5g/dl, renal impairment where serum

creatinine > 265 µmol/l) and clinical (e.g. impaired consciousness

or coma, multiple convulsions, pulmonary edema) findings. Accordingly,

severe (complicated) malaria cases are admitted to the medical

intensive care unit (MICU) or the short stay unit, while uncomplicated

cases are managed in an outpatient setting. A variety of anti-malarial

medications are prescribed, such as: Patients diagnosed with

uncomplicated and complicated/severe P. falciparum

infection were treated with chloroquine and quinine plus doxycycline

(adults)/or clindamycin (children)/or artemether and lumefantrine

combination, respectively. Chloroquine, followed by primaquine is

recommended for patients with P. vivax malaria. Those with mixed infections are usually treated as P. falciparum malaria.

All

samples undergo screening for the malaria parasite through microscopic

examination with Giemsa staining of thin and/or thick blood films.

Furthermore, the malaria focal point of MoPH’s communicable disease

control section conducted the epidemiological investigation and

follow-up. All patients diagnosed with malaria were treated with

anti-malarial medication as per the current guidelines for malaria

treatment at HMC.

Results

A

total of 4092 malaria cases reported during 2008-2015 were analyzed to

describe the epidemiological features of imported malaria in the State

of Qatar, using demographic profiling through parameters such as age,

gender, nationality (either Qatari, or migrant expatriates who have

lived in Qatar for at least 1 year), travel history, time of malaria

reporting, and Plasmodium species.

All

cases were imported and underwent parasitological confirmation through

microscopy; where no relapses were reported. Additionally, all patients

received anti-malarial treatment with no accurate information about how

many people exactly received such treatment. Therefore, none of the

malaria patients were followed-up for 28 days. Furthermore, twelve

cases of complicated or severe malaria have been documented throughout

2014 and 2015, and one of them was fatal. The causative organisms in

more than half of such cases were P. falciparum (58.3%), followed by P. vivax (33.3 %), and mixed infection (8.3 %).

The

annual number of imported malaria cases in Qatar has nearly tripled

from 216 cases in 2008 to 728 cases in 2013. However, the number of

malaria cases has declined to reach 445 cases in 2015. The demographic

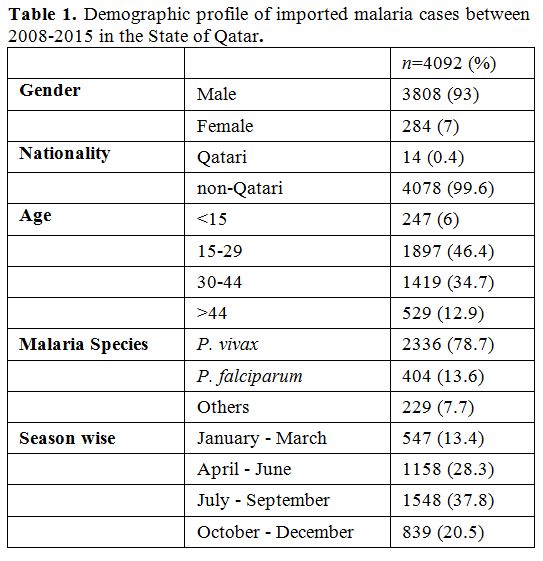

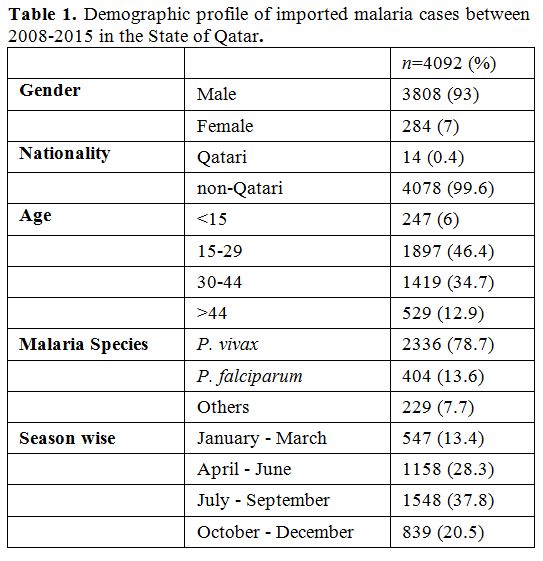

features of the imported cases (Table 1)

show that the majority of cases were males (93%), non-Qatari (99.6%),

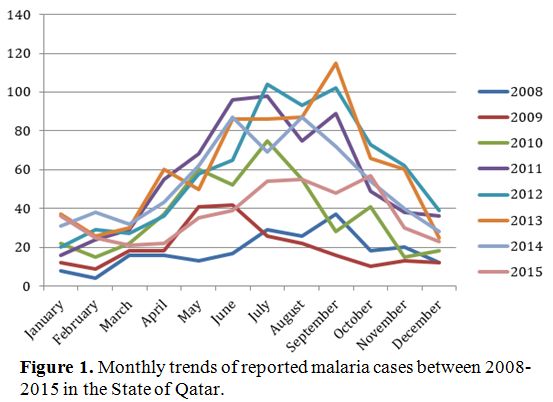

and aged 15 to 44 years (82.1%). In addition, almost a third (33.1%) of

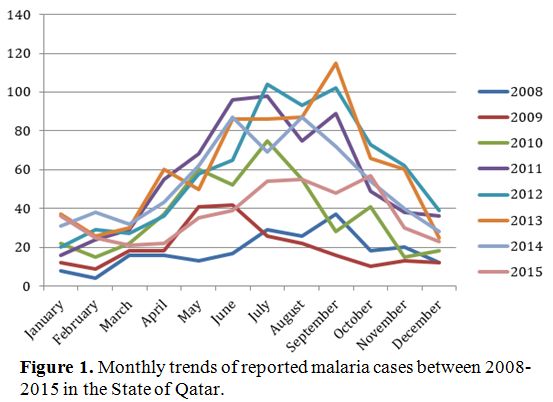

the cases were reported between July and September (Figure 1). Furthermore, between 2008-2009 and 2012-2015, P. vivax

was found to be the main etiologic agent accounting for more than

three-quarters (78.7%) of the cases. In addition, during the time above

period, P. falciparum was found to be responsible for almost one-seventh (13.6%) of the cases. However, data on the causative Plasmodium species during 2010 and 2011 were not recorded and thus are not reported in this study.

|

Table 1.

Demographic profile of imported malaria cases between 2008-2015 in the State of Qatar. |

|

Figure 1. Monthly trends of reported malaria cases between 2008-2015 in the State of Qatar. |

A

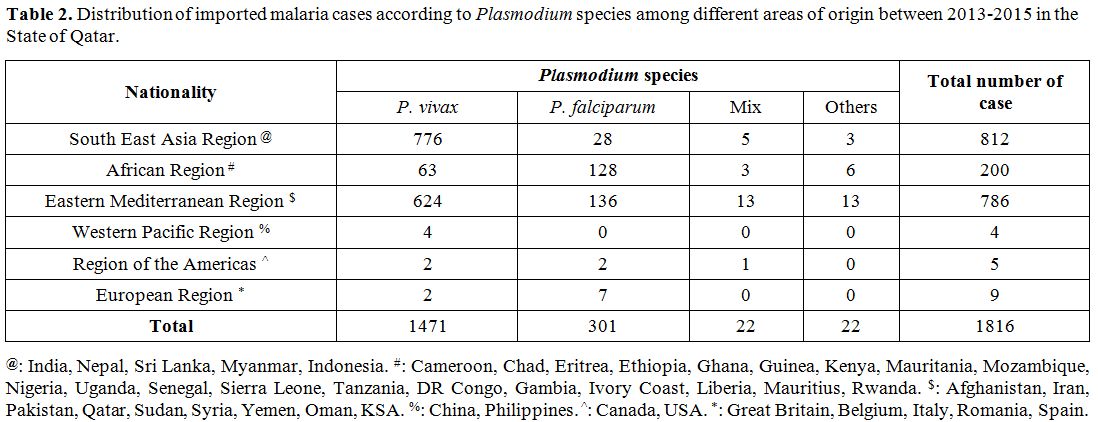

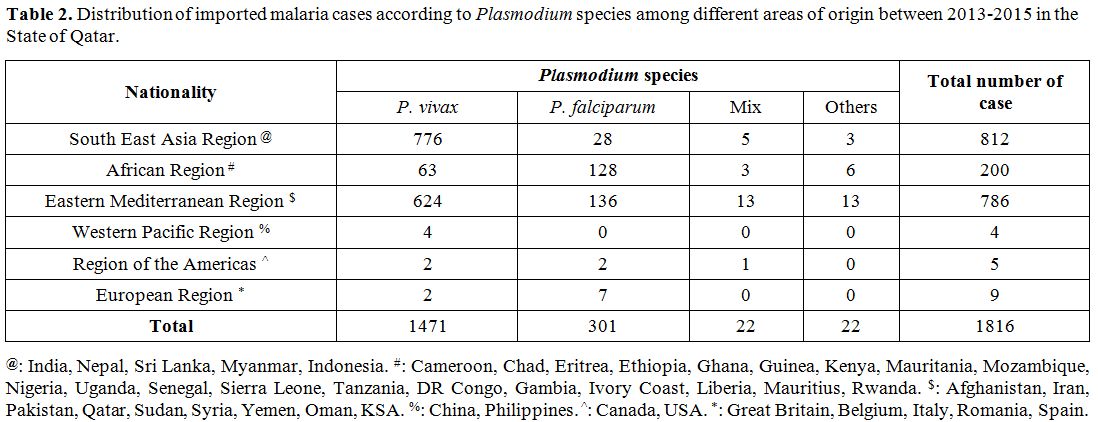

total of 1,816 malaria cases were reported between 2013 and 2015 to the

surveillance section at the Ministry of Public Health, Qatar. After

further analysis, the regional distribution of the cases’ country of

origin revealed that almost half originated from the South East Asia

Region (44.7%) and the other half from the Eastern Mediterranean Region

(43.2%) (Table 2). The

distribution of malaria cases by nationality and country of origin

reveal that all cases have contracted the malarial infection from

patient’s country of origin and due to travel to endemic countries.

|

Table

2. Distribution of imported malaria cases according to Plasmodium

species among different areas of origin between 2013-2015 in the State

of Qatar. |

Discussion

Malaria

continues to be the most important vector-borne infectious disease and

a major health problem in South East Asia and Africa. One of the main

factors contributing to this sustained burden is the emergence and

spread of anti-malarial drug resistance as well as vector resistance to

insecticides.[10] In addition to that, increased

international travel and dramatic climate changes have disturbed the

conventional epidemiological pattern of endemic infectious diseases.

In the present study, the majority of cases were male, non-Qatari, presented at >15 years of age, P. vivax was the main etiologic agent and occurred between July and September; which corroborates with previous studies in Qatar[7,9] and those of neighboring Gulf countries.[11-13]

These data indicate that imported malaria in Qatar has shown an

increase after a long period of constant reduction, and most cases

occurred between July and September, which confirms that the infection

was imported from patients’ respected countries during the summer

vacation.[7,9] Furthermore, the

reason of higher malaria cases in the male gender and 25 years old age

group in the current study must be due to the massive influx of single

male expatriates as labor from malaria-endemic regions of South East

Asian Countries and African continents. This pattern has also been

reported from previous studies in the Gulf region and western

countries.[11,13-15]

The Gulf

Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have accomplished against malaria

control; however, the region has witnessed the influx of a large

immigrant workforce, which travels to and from the respective home

countries annually. Moreover, such labor force arises primarily from

the malaria-endemic countries of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Therefore, imported malaria can pose a significant threat to malaria

control programs and the prospect of elimination in some of GCC

countries, where transmission has been interrupted previously. In the

United Arab Emirates, almost 3239 cases of imported malaria were

identified; the majority of which (90%) originated from Pakistan and

India. On the other hand, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia reported 1912

cases of imported malaria; almost a third of which (30%) originated

from neighboring Yemen. In addition to that, the majority (89%) of the

528 imported malaria cases in the Kingdom of Bahrain were among

nationals of India and Pakistan.[16]

It is well documented that mostly Indo-Gangetic plains, Northern hilly states, Northwestern and Southern India have < 10% P. falciparum, and the rest are P. vivax infections,[17] whereas, in African countries, P. falciparum is predominant.[6] In the present study, P. vivax was more commonly isolated in patients from India, Nepal, and Pakistan. On the other hand, P. falciparum

was more commonly found among patients from Sudan. These findings are

consistent with previous findings of research from neighboring Gulf

countries.[11-13,18,19]

In the

present study, our data clearly indicate that imported malaria in Qatar

has constantly increased from 2008 to 2013 and those most affected were

adult male migrants from endemic countries such as India, Nepal,

Pakistan, and Sudan. The increase in the total number of reported

imported malaria cases between the 2008 and 2015 could be explained by

the increased influx of foreign workers from malaria-endemic countries.

In 2015, WHO’s theme for World Malaria Day was “Invest in the Future:

Defeat Malaria”, which highlights the advances made in preventing,

controlling, and eliminating malaria globally. Consequently, to reduce

the importation of malaria cases into the State of Qatar, the Ministry

of Public Health (MoPH) held a public health awareness campaign

targeting all travelers to malaria-endemic countries. Moreover, the

ministry provides free malaria prophylaxis in travel clinics, which

could explain the decline of malaria incidence during 2014-2015 in

Qatar.

Imported malaria in Qatar has witnessed an increase

during the past seven years, despite a long period of constant

reduction; where the people most affected were adult male migrants from

endemic countries. Additionally, challenges as a weak malaria

surveillance system, lack of malaria awareness among health

professionals as well as travelers, and a lack of cooperation among

stakeholders must be mitigated to prevent malaria reintroduction in the

country. With infrastructure expansions and new development in Qatar as

the country prepares to host the FIFA World Cup soccer tournament in

2022, it is expected that there will be a large influx of tourists,

foreign workers, and those visiting friends and relatives. Therefore,

the incidence of cases and the risk of malaria reintroduction are also

likely to increase. Thus, an enhanced and robust surveillance program

should be implemented to reduce imported malaria cases in the State of

Qatar.

Acknowledgments

We

would like to acknowledge Mr. Redentor Cuizon Ramiscal, the

nurse-in-charge of the malaria notification forms and the surveillance

section under the Public Health Department at the Ministry of Public

Health, for his kind support and facilitation of our study.

References

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2017. Geneva: WHO Press; 2017.

- Fact Sheet: World Malaria Report 2015 [Internet]. who.int. 2016 [cited 15 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/malaria/media/world-malaria-report-2015/en/

- Committee on Malaria Vaccines. Vaccines against malaria. 1st ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 1996.

- Smith

A, Bradley D, Smith V, Blaze M, Behrens R, Chiodini P et al. Imported

malaria and high risk groups: observational study using UK surveillance

data 1987-2006. BMJ. 2008;337(jul03 2):a120-a120.

- Franco-Paredes

C, Santos-Preciado JI. (2006) Problem pathogens: prevention of malaria

in travellers. Lancet Infect Dis. 6 (3): 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70410-8

- Beljaev A. The malaria situation in the WHO eastern Mediterranean region. Meditsinskaia Parazitologiia. 2000;(2):12-5.

- Al-Kuwari M. Epidemiology of Imported Malaria in Qatar. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2009;16(2):119-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00285.x PMid:19335812

- Qatar - International tourism [Internet]. Indexmundi.com. [cited 15 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/qatar/international-tourism

- Khan

F, Lutof A, Yassin M, Khattab M, Saleh M, Rezeq H et al. Imported

malaria in Qatar: A one year hospital-based study in 2005. Travel

Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2009;7(2):111-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.003 PMid:19237144

- Status report on artemisinin and ACT resistance (April 2017) [Internet]. who.int. 2017 [cited 15 March 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241500479/en/index.html

- Iqbal J, Al-Ali F, Sher A, Hira P. Imported Malaria in Kuwait (1985-2000). Journal of Travel Medicine. 2003;10(6):324-329. https://doi.org/10.2310/7060.2003.9291 PMid:14642198

- Ismaeel

AY, Senok AC, Jassim Al-Khaja KA, Botta GA . Status of malaria in the

Kingdom of Bahrain: a 10-year review. J Travel Med 2004; 11: 97 – 101. https://doi.org/10.2310/7060.2004.17059 PMid:15109474

- Bashwari

L, Mandil A, Bahnassy A, Al-Shamsi M, Bukhari H. Epidemiological

profile of malaria in a university hospital in the eastern region of

Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2001;22(2):133-8. PMid:11299407

- Dar

F, Bayoumi R, AlKarmi T, Shalabi A, Beidas F, Hussein M. Status of

imported malaria in a control zone of the United Arab Emirates

bordering an area of unstable malaria. Transactions of the Royal

Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;87(6):617-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(93)90261-N

- Lobel

H, Baker M, Gras F, Stennies G, Meerburg P, Hiemstra E et al. Use of

Malaria Prevention Measures by North American and European Travelers to

East Africa. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2001;8(4):167-172. https://doi.org/10.2310/7060.2001.22206 PMid:11703900

- Snow

R, Amratia P, Zamani G, Mundia C, Noor A, Memish Z et al. The Malaria

Transition on the Arabian Peninsula: Progress toward a Malaria-Free

Region between 1960–2010. Advances in parasitology. 2013;82:205–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00003-4 PMid:23548086 PMCid:PMC3951717

- Kumar

A, Valecha N, Jain T, Dash A. Burden of malaria in India: retrospective

and prospective view. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and

Hygiene. 2007;77(6):69-78. PMid:18165477

- Al-Seghayer

SM, Kenawy MA, Ali OTE . Malaria in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

epidemiology and control . Sci J King Faisal University 1999; 1: 6 –

20.

- Al-Tawfiq

J. Epidemiology of travel-related malaria in a non-malarious area in

Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2006;27(1):86-9. PMid:16432601

[TOP]