Naouel Guirat Dhouib1, Monia Ben Khaled1, Monia Ouederni1, Imen Ben-Mustapha2, Ridha Kouki1, Habib Besbes1, Mohamed Ridha Barbouche2, Fethi Mellouli1 and Mohamed Bejaoui1.

1 Pediatric Immunohematology Department, Bone Marrow Transplantation Center Tunis, Tunisia.

2

Laboratory of Transmission, Control and Immunobiology of Infections

(LR11IPT02), Institut Pasteur de Tunis, 1002 Tunis, Belvédère, Tunisia.

Correspondence to: Naouel Guirat Dhouib, Pediatric Immunohematology

Department, Bone Marrow Transplantation Center Tunis, Tunisia. Tel: +

216 98 644165. E-mail:

nawel.guirat@yahoo.fr

Published: November 1, 2018

Received: August 27, 2018

Accepted: October 15, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018065 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.065

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Skin

manifestations are frequent among patients with primary

immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs). Their prevalence varies according to

the type of immunodeficiency. This review provides the reader with an

up-to-date summary of the common dermatologic manifestations of PIDs

among Tunisian children. We conducted a prospective study on two

hundred and ninety children with immune deficiency. Demographic details

(including age, sex, and consanguinity) with personal and family

history were recorded. Special attention was paid to cutaneous

manifestations. Dermatological involvements were grouped according to

the etiology of their most prominent sign. Cutaneous manifestations

were found in 164 patients (56.5%). They revealed the diagnosis of PIDs

in 71 patients (24.5 %). The mean age at presentation was 21 months.

Overall the most prominent cutaneous alterations were infectious. They

accounted for 106 cases (36.55%). The most prevalent causes of

cutaneous infections were bacterial: 93 cases (32.06%). Immuno-allergic

skin diseases were among the common findings in our study. These

include eczematous dermatitis found in 62 cases (21.38%). Malignancy

related PIDs was seen in a boy with Wiskott Aldrich syndrome. He

developed Kaposi’s sarcoma at the age of 14 months. Cutaneous changes

are common among children with PIDs. In pediatric patients with failure

to thrive, chronic refractory systemic manifestations often present in

other family members, recurrent cutaneous infections unresponsive to

adequate therapy, atypical forms of eczematous dermatitis or unusual

features should arouse the suspicion of PIDs and prompt specialized

immunologic consultation should be made.

|

Introduction

Primary

immunodeficiency disorders (PIDs) refer to a heterogeneous group of

rare disorders characterized by poor or absent function of one or more

components of the immune system. Over 270 different disorders have been

identified to date, with new disorders continually being recognized.[1]

The clinical presentation of PIDs is highly variable; however, most

disorders involve increased susceptibility to infection. Cutaneous

manifestations are common in PIDs, affecting half of the pediatric

cases and often precede the final diagnosis. Skin infections

characterize many primary immune deficiencies, but noninfectious

cutaneous involvements are frequent including allergic, inflammatory,

autoimmune and malignant manifestations.[2] Only few

studies describing the spectrum of skin disorders in PID are available,

and no similar studies have been conducted in Tunisia. This prospective

study provides the reader with an up-to-date summary of the common

dermatologic manifestations of primary immune deficiency diseases among

Tunisian children.

Materials and Methods

We

conducted a prospective study on two hundred and ninety children

referrals children with suspected immune deficiency during a 10-year

period (January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2017) at the Pediatric

Immunohematology Department in the National Bone Marrow Transplantation

Center in Tunis. Individuals with human immunodeficiency virus

infection or receiving immunosuppressive therapy were excluded from the

study. Demographic details (including age, sex, and consanguinity) with

personal and family history were recorded. Special attention was paid

to cutaneous manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of PIDs were

classified into four categories: cutaneous lesions of infectious

origin, immunoallergic/autoimmune skin manifestations, pathognomonic

findings related to complex phenotypes and skin cancers associated with

PIDs. The diagnosis of PIDs was established according to the criteria

defined by the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert

Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency.[1] Informed written consent to publish images was obtained from parents.

Results

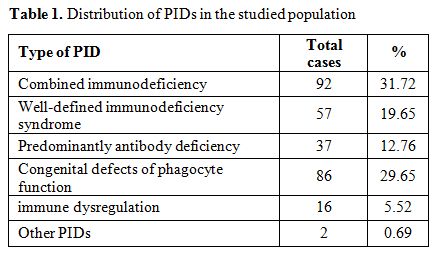

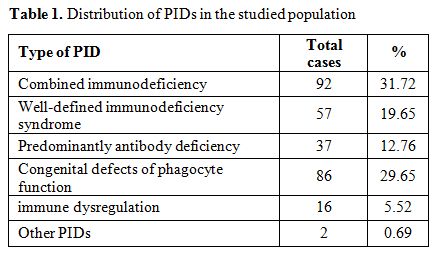

Among the two hundred and ninety children (Table 1),

111 (38%) were female, and 179 (62%) were male. Consanguineous

relationships were seen in almost two-thirds of patients (65.17%).

Cutaneous manifestations were found in 164 patients (56.5%). They

revealed the diagnosis of PIDs in 71 patients (24.5 %). The mean age at

presentation was 21 months (1 day-25 years). The most predominant

cutaneous alterations were infectious in 106 cases (36.55%). The most

prevalent causes of cutaneous infections were bacterial: 93 cases,

(32.06%).

|

Table 1.

Distribution of PIDs in the studied population |

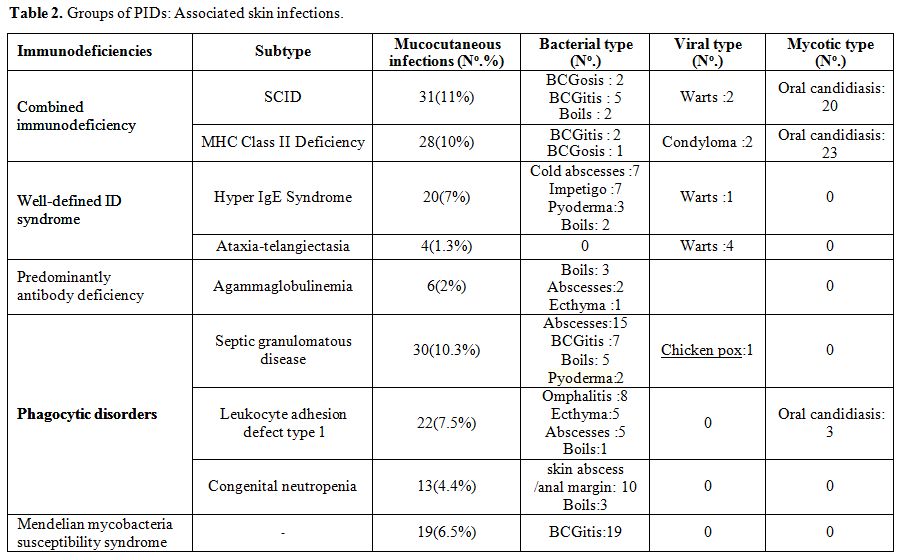

Staphylococcus aureus represented by far the most common pathogen (32 cases), and Pseudomonas

was responsible for one other case. Unfortunately bacterial culture was

not done in all infections. BCG infections were common among patients

with combined immunodeficiency (CID) and septic granulomatous disease

while anal margin abscesses were frequently seen in phagocytic

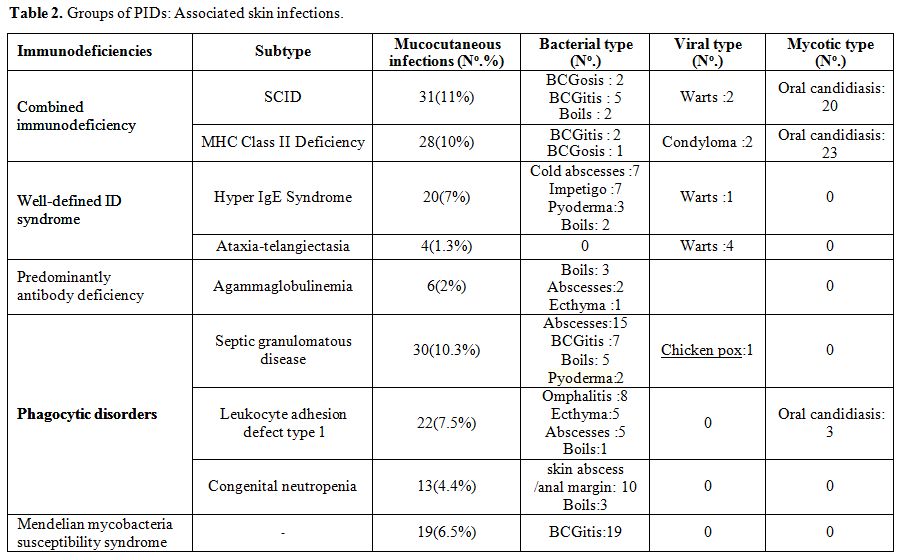

disorders (Table 2). The next

type of skin infection consisted of viral infections seen in 11 (3.8%)

of the studied patients. Most of them had warts. Recurrent oral

papillomatous lesions related to human papillomavirus were seen in 2

sisters with major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency (Figure 1). The third type was fungal skin infection (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Groups of PIDs: Associated skin infections. |

|

Figure 1.

Disseminated warts on oral cavity in a patient with MHC class II deficiency. |

In

this study, oral candidiasis was the most common infection in patients

with CID, frequently associated with broncho-pulmonary infections (61

cases, 66.30%), digestive infections (56 cases, 60.9%), ear, nose, and

throat infections (23 cases, 25%) and persistent diarrhea resulting in

failure to thrive (39 cases, 42.4%). Mucocutaneous lesions due to

candida were more frequently oral, whitish, adherent plaques and

paronychia (Figure 2).

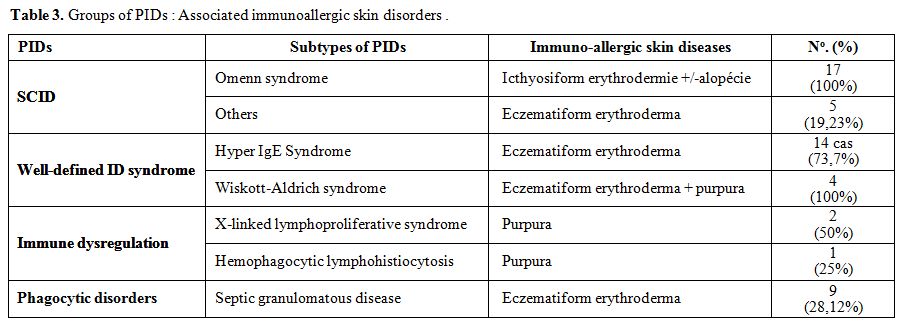

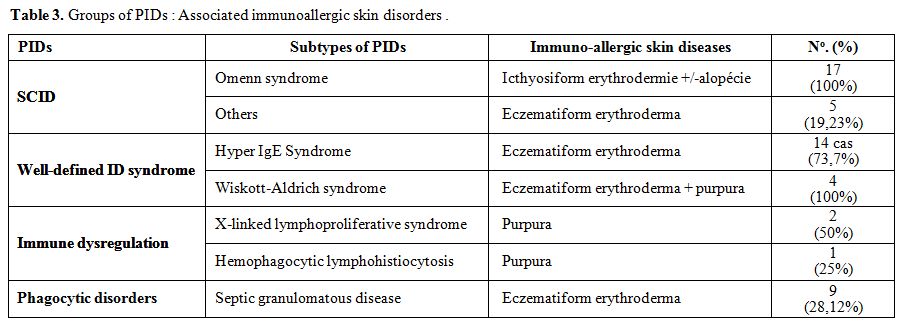

Immuno-allergic skin diseases were among the common findings in our

study. These include eczematous dermatitis found in 62 cases (21.38%), (Table 3). Severely generalized erythroderma with alopecia revealed Omenn syndrome in 17 cases (Figure 3 and 4).

Mean patient age at the onset of these cutaneous manifestations was 6.4

months (1 day to 48 months). Other extracutaneous manifestations led to

the diagnosis including recurrent infections observed in 11 patients

with failure to thrive, as well as infiltration of lymphoid organs with

hepatosplenomegaly. Lymphopenia was found in 15 patients

(88 %) and eosinophilia in 16 cases (94%). Specific

muco-cutaneous manifestations of PIDs were seen in 22 cases (7.6%)

among them telangiectasia (Figure 5)

revealed ataxia telangiectasia syndrome in 14 cases (100%). Among these

patients, three had hypopigmented and café-au-lait macules. Cutaneous

albinism was noted in 8 other cases with Chediack Higashi syndrome

(five cases), Griscelli syndrome (one case) or Hermanski pudlak type 2

syndrome (two cases). Malignancy related PIDs was seen in a boy with

Wiskott Aldrich syndrome. He developed Kaposi’s sarcoma at the age of

14 months (Figure 6).

|

Figure 2.

Oral candidiasis in a patient with SCID. |

|

Table 3. Groups of PIDs: Associated immunoallergic skin disorders. |

|

Figures 3 and 4. Erythroderma with alopecia in a patient with Omenn syndrome.. |

|

Figure 5. Conjunctival telangiectasias in a patient with ataxia telangiectasia syndrome. |

|

Figure 6. Kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. |

Discussion

Cutaneous

manifestations may be the clue for the diagnosis of PIDs because of

their early appearance, their high frequency and their easy access for

examination.[3] This study showed that cutaneous

alterations were the presenting problem in 56.5% of cases, which are

higher than what is reported by Moin et al., (32%) and Al-Herz et al.,

(48%).[4,5] Although skin infections were the

most common manifestations, the prevalence rate of infections in our

series was lower than those reported in other countries.[4,6]

Pyogenic infections of the skin frequently occur in PIDs causing

abscesses, boils, ecthyma, cellulitis, folliculitis, or impetigo (Table 2). In this study, recurrent abscesses were frequent. They predominated in phagocytic defects and hyper IgE syndrome.[7]

They tended to be multiple, recurrent and difficult to control.

Bacteriologic cultures should be performed since the growth of unusual

organisms is not infrequent. The most common organism is Staphylococcus followed by Haemophilus, Serratia, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas. In leucocyte adhesion deficiency, recurrent skin infections, generally due to Staphylococcus aureus

or Gram negative bacilli is typical. It tends to necrotize and

ulcerate without pus at the wound site. Other features include

delayed umbilical cord separation, omphalitis, persistent leukocytosis,

and severe destructive gingivitis and periodontitis leading to tooth

loss and alveolar bone resorption.[8] Mycobacterium

bovis in Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine can cause serious

complications in patients with PIDs ranging from prolonged disease with

lymphadenopathy (BCGitis) to disseminated disease (BCGosis).[9]

These complications have been diagnosed in immunocompromised patients

including combined immunodeficiency, mendelian susceptibility to

mycobacterial disease, chronic granulomatous disease, complete DiGeorge

syndrome, hyper-IgM and hyper-IgE syndromes.[10,11]

The median age of onset is three months of age. Our study showed that

severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCID), MHC Class II Deficiency, CGD

and mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease are the most

common forms of immunodeficiencies among children with BCGosis/BCGitis.

A large study conducted by De Beaucoudrey et al., reported 108 cases

with IL12R β1 deficiency, among them 84 cases presented BCGitis.[12] Similar results were reported by Galal et al.[10]

In our study, 10 out of 13 patients with mendelian susceptibility to

mycobacterial disease had developed suppurative BCG lymphadenitis.

Since the routine national vaccination program in Tunisia includes BCG

vaccine, PIDs, should be considered in any patient with prolonged

BCGitis or BCGosis. Awareness of this phenomenon is important because

these patients need to be treated with antitubercular drugs. Children

with PID are rarely exposed to common viral skin infections as viral

wart and molluscum contagiosum contrasting, thus, with their high

frequency in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Herpes

simplex virus is among the most common viral skin infections

encountered in T-cell deficient patients. The symptoms are often

impressive and are relatively resistant to conventional treatment.[4,5]

In the present study, recurrent oral papillomatous lesions related to

human papillomavirus were seen in two sisters with major

histocompatibility complex class II deficiency.[13]

Warts, described as benign skin growths that develop on different parts

of the body and can take on various forms, disseminated warts were

found in 2 patients with WHIM syndrome and ataxia telangiectasia.

Persistent mucocutaneous candidiasis may

be the initial presenting sign for PID in infancy, especially

in those with severe combined immunodeficiency disease.[2,5]

In this study, 76.92% (20/26 cases) with severe combined

immunodeficiency had at least one episode of oral candidiasis.

Candidiasis associated with eczema is a common feature of Hyper IgE

syndrome.[2] When present with mucocutaneous

candidiasis, autoimmune endocrinopathies, and dystrophy of the dental

enamel and nails, it is important to recall the autoimmune

polyendocrinopathy- candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome. This

syndrome is caused by mutations in the autoimmune regulator gene

(AIRE), resulting in autoreactive T-cells which develop autoantibodies.[14]

Immunodeficiency should be suspected when skin infection have a

multifocal character, saprophytic or opportunistic and/or a combination

of several pathogens as well as their persistence or their repetition

despite a good anti- infective treatment or when there are skin changes

leading to diagnosis difficulties. Eczematous dermatitis is another

nonspecific cutaneous finding among several PIDs including IgA

deficiency, Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy and enteropathy,

common variable immunodeficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich

syndrome, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, hyper IgM syndromes, hyper

IgE, Netherton’s syndrome and Omenn syndrome. The overall prevalence of

eczema in our patient population (21.38%) was comparable with that in

Mexico (22%) but higher than that reported from Libya (12%).[6,15]

Although

widely present in PIDs, eczema was a consistent feature in patients

with Wiskott- Aldrich syndrome(WAS), a complex and severe X-linked

disorder characterized by microthrombocytopenia, eczema, increased

susceptibility to infection, and increased risk in developing

autoimmunity and lymphomas.[16] Other cutaneous and

mucosal manifestations and hemorrhages are frequent in WAS patients

ranging from non-life-threatening (epistaxis, petechiae, purpura, oral

bleeding) to severe manifestations. This heterogeneous syndrome may be

complicated by autoimmune mucocutaneous manifestations including

Henoch–Schönlein-like purpura, dermatomyositis and recurrent

angioedema.[17] In a clinical series conducted by

Ouederni, eczema was observed in four patients among 35 MHC Class

II Deficiency patients.[18] An underlying primary

immunodeficiency should also be suspected when a patient shows severe

early-onset, atypical, eczematous dermatitis, refractory to therapy

with a tendency to become extensive and flaring up with systemic

infections chronic diarrhea and failure to thrive[19]

or family history suggestive of immunodeficiency in patients with

severe atopic dermatitis. These features underscore the importance of

eliciting a history of recurrent infections or family history

suggestive of immunodeficiency in patients with severe atopic

dermatitis.[20]

A cutaneous granuloma is a

histopathological diagnosis on a tissue that is usually taken for the

evaluation of the cause of an unexplained nodular swelling in the skin.

Aghamohammadi reported a 27-year-old patient with CVID who presented

with multiple skin granulomas on both hands. The patient had been well

until the age of 20 years when she developed these skin lesions with

frequent upper respiratory infections and recurrent diarrhea.

Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy improved skin lesions. In our study,

one patient with CVID developed annular granuloma of the right leg.

Erythroderma

with diffuse alopecia was the third most common skin manifestation in

children with SCID and a consistent presenting feature in infants with

Omenn syndrome, a rare inherited combined immunodeficiency caused by

mutations in various SCID genes. Erythroderma can occur from birth or

develop during the first weeks of life. It is evocative by its

infiltrated character. These patients show hypereosinophilia,

associated with T cell infiltration of gut, liver, spleen, and skin

leading to erythroderma, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, alopecia,

recurrent infection, and failure to thrive.

Our findings support the results of other studies that most PIDs have cutaneous features.

These

features, being their aspects typical, are highly suggestive for the

diagnosis of PIDs. One of the specific cutaneous manifestations of PIDs

is telangiectasia. This PID is caused by alterations in the ATM gene

leading to telangiectasia, immunodeficiency with progressive ataxia and

oculomotor apraxia often accompanied by extrapyramidal movement

disorders.[21,22] In most cases, telangiectasias

first appear when the child reaches three to five years of age.

Conjunctival telangiectasias are first noted in the interpalpebral

bulbar conjunctiva away from the limbus. Cutaneous telangiectasias are

seen on the ears, palate, bridge of the nose and later extend to the

neck, the dorsum of the hands and feet. In our study all patients with

ataxia telangiectasia had telangiectasia. Other skin manifestations

were reported including abnormalities of pigmentation (hypopigmented

and café-au-lait macules), poikiloderma, seborrheic dermatitis, and

less common findings including acanthosis nigricans and hirsutism.[23]

Hypopigmented macules were found in 2 other patients mainly on the

face, trunk, and hands. In our study, hypopigmented and café- au-lait

macules were seen in three cases. Another specific feature of PIDs is

partial albinism with silvery gray hair. This association is an

evocative or even pathognomonic cutaneous sign of complex PIDs

including Chediak Higashi, Griscelli, Hermansky-Pudlak, and

MAPBP-interacting protein deficiency syndromes.[24]

An association of PIDs and cancers has been known for many years[25]

and confirmed from data collected in established registries. The

overall risk for cancer developing in children with PIDs is estimated

to range from 4 to 25%.[26] In a recent study from

the United States Immune Deficiency Network conducted among 3658

patients, 171 separate cancers were diagnosed 25 (15%) of them were

skin cancers. There were 119 cancers (70%) in subjects with CVID.

Thirteen cancers (9%) were observed in subjects with

hypogammaglobulinema and agammaglobulinemia, and eight cancers

(4.6%) were observed in subjects with WAS.[27] Despite

the relatively high number of chronic granulomatous disease patients in

the registry (483), none were diagnosed with cancer. One of the studied

patients with Wiskott Aldrich syndrome developed a Kaposi’s sarcoma

at the age of 14 months.To our

knowledge, this patient is the first case described in the

literature.[28]

Conclusions

Cutaneous

changes may be the presenting signs of PIDs and serve as important

clues for pediatric patients with PIDs. They may also be life-saving in

patients with severe PIDs. Early diagnosis and treatment will prevent

associated morbidity and mortality and improve the quality of life. In

pediatric patients with failure to thrive, chronic refractory

systemic manifestations often present in other family members,

recurrent cutaneous infections unresponsive to adequate therapy,

atypical forms of eczematous dermatitis or unusual features should

arouse the suspicion of PIDs and prompt specialized immunologic

consultation should be made.

References

- Picard C, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL,

Chatila T, Conley ME, Cunningham-Rundles C, Etzioni A, Holland SM,

Klein C, Nonoyama S, Ochs HD, Oksenhendler E, Puck JM, Sullivan KE,

Tang ML, Franco JL, Gaspar HB. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases: an

Update on the Classification from the International Union of

Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency

2015. J Clin Immunol. 2015 Nov; 35(8):696-726 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10875-015-0201-1 PMID:26482257

- Lehman H. Skin manifestations of primary immune deficiency. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2014;46:112 119 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8377-8 PMID:23760761

- Smitt

JHS, Wulffraat NM, Kuijpers TW. The skin in primary immunodeficiency

disorders. Eur J Dermatol 2005;15: 425- 432. PMID:16280293

- Moin

A , Farhoudi A, Moin M, Pourpak Z, Bazargan N. Cutaneous Manifestations

of Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases in Children. Iran J Allergy Asthma

Immunol 2006;5:121-126. http://dx.doi.org/05.03/ijaai.121126 PMID:17237563

- Al Herz W, Nanda A. Skin manifestations in primary immunodeficient children. Pediatr Dermatol 2011; 28:494 501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01409.x PMID:21453308

- Suleman

Elfaituri S, Matoug I .Cutaneous Manifestations of Primary

Immunodeficiency Diseases in Libyan Children. J Clin Dermatol Ther

2017;4: 025. http://dx.doi.org/10.24966/CDT-8771/100025

- Yu

JE, Azar AE, Chong HJ, Jongco AM 3rd, Prince BT. Considerations in the

Diagnosis of Chronic Granulomatous Disease. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc

2018; 7(suppl 1):S6-S11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piy007 PMID:29746674

- Johnston

S L. Clinical Immunology Review Series: An approach to the patient with

recurrent superficial abscesses. Clin Exp Immunol 2008; 152(3):397–405.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03640.x PMID:18422735

- Movahedi

Z, Norouzi S, Mamishi S, Rezaei N. BCGiosis as a presenting feature of

a child with chronic granulomatous disease. Braz J Infect Dis 2011;15:

83-86.PMID:21412596

- Galal N , Boutros J,

Marsafy A, Kong XF, Feinberg J, Casanova JL, Boisson-Dupuis S,

Bustamante J. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease in

egyptian children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2012.033 PMID:22708048

- Norouzi

S, Aghamohammadi A, Mamishi S, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)

complications associated with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J

Infect 2012;64:543–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2012.03.012 PMID:22430715

- De

Beaucoudrey L, Samarina A, Bustamante J, Cobat A, Boisson-Dupuis S, et

al. Revisiting human IL-12Rβ1 deficiency: a survey of 141 patients from

30 countries. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010; 89: 381-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181fdd832 PMID:21057261

- Guirat-Dhouib

N , Baccar Y, Mustapha IB, Ouederni M, Chouaibi S, El Fekih N,

Barbouche MR, Fezaa B, Kouki R, Hmida S, Mellouli F, Bejaoui M. Oral

HPV infection and MHC class II deficiency (A study of two cases

with atypical outcome). Clin Mol Allergy. 2012 Apr 23;10(1):6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1476-7961-10-6 PMID:22524894

- Collins

SM, Dominguez M, Ilmarinen T, Costigan C, Irvine D. Dermatological

manifestations of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal

dystrophy syndrome. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:1088 - 1093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07166.x PMID:16704638

- Berron-Ruiz

A, Berron-Perez R, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Cutaneous markers of primary

immunodeficiency diseases in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000

Mar-;17(2):91-6. PMID:10792794

- Imai K, Morio T, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course of patients with WASP gene mutations. Blood 2004;103:456-464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-05-1480 PMID:12969986

- Catucci

M, Castiello MC, Pala F, Bosticardo M, Villa A. Autoimmunity in

wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: an unsolved enigma. Front

Immunol.2012;3:209. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00209 PMID:2282671

- Ouederni

M, Vincent QB, Frange P, et al: Major histocompatibility complex class

II expression deficiency caused by a RFXANK founder mutation: a survey

of 35 patients Blood 2011;118(19):5108-5118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-05-352716 PMID:21908431

- Szczawinska-Poplonyk

A, Kycler Z, Pietrucha B, Heropolitanska-Pliszka E, Breborowicz A, et

al. The hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome - clinical manifestation

diversity in primary immune deficiency. J Rare Dis 2011 ;6:76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-6-76 PMID:22085750

- Aghamohammadi

A, Moghaddam ZG, Abolhassani H, Hallaji Z, Mortazavi H, Pourhamdi S, et

al. Investigation of underlying primary immunodeficiencies in patients

with severe atopic dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2014;

42(4):336- 341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aller.2013.02.004 PMID:23735167

- Chiam

LY, Verhagen MM, Haraldsson A, Wulffraat N, Driessen GJ, Netea MG,

Weemaes CM, Seyger MM, van Deuren M. Cutaneous granulomas in ataxia

telangiectasia and other primary immunodeficiencies: Reflection of

inappropriate immune regulation? Dermatology 2011;223(1):13-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000330335 PMID:21876338

- Carranza

D, Vega AK, Torres Rusillo S, Montero E, Martinez LJ, Santamaría M, et

al. Molecular and functional characterization of a cohort of Spanish

patients with ataxia telangiectasia. Neuromolecular Med 2017;

19(1):161-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12017-016-8440 PMID:27664052

- Greenberger

S , Berkun Y, Ben-Zeev B, Levi YB, Barziliai A, Nissenkorn A.

Dermatologic manifestations of ataxia- telangiectasia syndrome. J Am

Acad Dermatol 2013;68(6):932-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.950 PMID:23360865

- Dotta

L, Parolini S, Prandini A, Tabellini G, Antolini M, Kingsmore SF,

Badolato R . Clinical, laboratory and molecular signs of

immunodeficiency in patients with partial oculo- cutaneous albinism.

Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 17(8):168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-168 PMID:24134793

- Notarangelo LD .PIDs and cancer: an evolving story. Blood 2010;116(8):1189-1190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-06-286179 PMID:20798238

- Mortaz

E, Tabarsi P, Mansouri D, Khosravi A, Garssen J, Velayati A, Adcock IM.

Cancers Related to Immunodeficiencies: Update and Perspectives. Front

Immunol 2016;7:365.e Collection 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00365 PMID: 27703456

- Mayor

PC, Eng KH, Singel KL, Abrams SI, Odunsi K, Moysich KB, Fuleihan R,

Garabedian E , Lugar P, Ochs HD, Bonilla FA, Buckley RH, Sullivan KE,

Ballas ZK, Cunningham-Rundles C, Segal BH. Cancer in primary

immunodeficiency diseases: Cancer incidence in the United States Immune

Deficiency Network Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2018;141(3):1028-1035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.024 PMID:28606585

- Picard

C , Mellouli F, Duprez R, Chédeville G, Neven B, Fraitag S, Delaunay J,

Le Deist F, Fischer A, Blanche S, Bodemer C, Gessain A, Casanova JL,

Bejaoui M. Kaposi's sarcoma in a child with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Eur J Pediatr.2006;165(7):453-457. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0107-2 PMID:16602009

[TOP]