Emilia Matos do Nascimento1,2, Clarisse Lopes de Castro Lobo2, Basilio de Bragança Pereira3,4,5 and Samir K. Ballas2,6.

1 UEZO - Centro Universitário Estadual da Zona Oeste, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

2 Clinical Hematology Division, Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti. HEMORIO, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

3 School of Medicine/UFRJ - Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

4 Postgraduate School of Engineering – COPPE/UFRJ.

5 Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital/UFRJ.

6 Cardeza Foundation, Department of Medicine, Jefferson Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Correspondence to: Samir K. Ballas MD FACP. Cardeza Foundation,

Department of Medicine, Jefferson Medical College, Thomas Jefferson

University, 1020 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107. Tel: 856 745

6380, Fax: 856 795 0809. E-Mail:

Samir.ballas@jefferson.edu

Published: March 1, 2019

Received: November 12, 2018

Accepted: January 12, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11(1): e2019022 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2019.022

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

The

clinical picture of patients with sickle cell anemia (SCA) is

associated with several complications some of which could be fatal. The

objective of this study is to analyze the causes of death and the

effect of sex and age on survival of Brazilian patients with SCA. Data

of patients with SCA who were seen and followed at HEMORIO for 15 years

were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Statistical modeling was

performed using survival analysis in the presence of competing risks

estimating the covariate effects on a sub-distribution hazard function.

Eight models were implemented, one for each cause of death. The

cause‐specific cumulative incidence function was also estimated. Males

were most vulnerable for death from chronic organ damage (p = 0.0005)

while females were most vulnerable for infection (p=0.03). Age was

significantly associated (p ≤ 0.05) with death due to acute chest

syndrome (ACS), infection, and death during crisis. The lower survival

was related to death from infection, followed by death due to ACS. The

independent variables age and sex were significantly associated with

ACS, infection, chronic organ damage and death during crisis. These

data could help Brazilian authorities strengthen public policies to

protect this vulnerable population.

|

Introduction

The

clinical picture of patients with sickle cell anemia (SCA) is

associated with several complications some of which could be fatal.[1-3]

Besides the recurrent episodes of acute vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs),

these complications include, among other things, stroke, acute chest

syndrome, splenic and hepatic sequestration, infections, priapism, leg

ulcers, retinopathy, avascular necrosis, cholelithiasis, progressive

organ failure and death.[3] The frequency and severity

of these complications vary with age, time and sex. Ischemic stroke,

for example, is more common in children whereas leg ulcers are more

common in adults.[3] The probability of the recurrence

of each complication at a certain age has not been well studied. The

objective of this study is to analyze the causes of death using the

competitive risk statistical model.[4] This analysis

is based on the recently reported retrospective data on the pattern of

morbidity and mortality in children, adolescents and adults in Rio de

Janeiro, Brazil.[5]

Material and Methods

Patients: Retrospective data were collected and analyzed in patients with SCA including patients with sickle-β0-thalassemia (Sβ0thal),

who were seen and followed at HEMORIO for 15 years from January 1,

1998, through December 31, 2012. Children and adults were included in

the study. The total number of patients enrolled was 1676. The

diagnosis of SCA including sickle-β0-thalassemia

was confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The

date and cause of death were confirmed from the patients’ charts if

death occurred at HEMORIO. Death outside HEMORIO was suspected if

patients failed to show up for follow-up and confirmed by interviews

with the patients’ families and from death certificates. None of the

patients was taking hydroxyurea. The study was approved by the

Institutional Review Board (IRB) of HEMORIO.

Statistical analysis. Statistical modeling was performed using Survival analysis in the presence of competing risks.

Basically,

three functions are used in survival data: the survival function, the

cumulative distribution function, and the hazard function.

In

survival analysis, it is common to investigate the lifetime related to

a single cause of death. However, there are more complex models, in

which the death of the individual is related to one of several possible

causes identified in the study. These models are called competing risk

models being suitable in studies where individuals are exposed to more

than one cause of failure or event.

Gooley et al.[6]

define the competing risk as a survival model in which the occurrence

of an event prevents or alters the probability of occurrence of another

event.

In general, three types of approach are used in the presence of competing risks:[6] 1 - Event-free survival model, using the Cox model[4]

considering the time until the occurrence of the first event. This

model is not suitable because it does not consider the various risk

factors; 2 – Cause-specific hazard model, where the Cox model is used

considering one of the events as the main cause and the rest are

censored. This approach is also unsuitable because it is not possible

to estimate the common effect of a covariate for competing outcomes.

Additionally, the sum of the cumulative distribution function for each

outcome is different from the cumulative distribution function of the

overall curve. It would also be necessary to be valid the assumption of

independence between the event of interest and other competing events,

considered censorship, which rarely occurs; and 3 – Hazard of

subdistribution model, using the cumulative incidence function. This

model does not require any assumption of independence of competing

risks.[7]

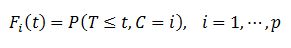

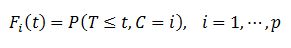

The cumulative incidence function, or subdistribution function, introduced by Kalbleisch & Prentice,[8] is defined as the joint probability

|

|

That is, Fi (t) is the probability of failure for a specific cause, among p possible causes over time.

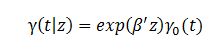

Fine and Gray[9]

proposed a regression model implemented on the cumulative incidence

function for analyzing competing risks. Modeling is performed by hazard

of subdistribution function, defined as the instantaneous hazard of an

individual suffering the event for a specific cause, conditional to

have survived until a certain time t.

Where γ is the hazard of subdistribution; γ0 is the baseline hazard of the subdistribution; β is a vector of coefficients to be estimated; and z is the vector of independent variables.

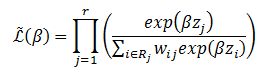

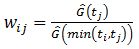

The partial likelihood function is modeled as an extension of the Cox proportional hazards model,[10] weighted by wij.

In this model, a patient who has suffered a competing risk is not removed from the risk set. This individual receives a

weight, where Ĝ is the nonparametric Kaplan-Meier[11] distribution of the censorship. The weight wij is decreasing due to the decay of the Kaplan-Meier curve. The distribution of the censorship is given by the pair (Ti,Ci) , and Ti is the time measured until the occurrence of the first competing event; and Ci=0 if it is observed the occurrence of some type of event and Ci=1 if no event occurs.[12] Thus, there is an inversion of the usual concepts of event and censorship.

In each instant tj,

in which the event of interest has been observed, the risk set is

composed of individuals who have not suffered any event until the time tj, receiving the weight wij=1; and those who have suffered a competing event before this time tj being weighted as wij≤1. Thus, given the occurrence of the event of interest in time tj, for each individual who has suffered a competing event in tj, the greater the distance between points ti and tj, the lower the weigh wij.[12] Results

The

causes of death of the 281 patients who died were analyzed. The most

common causes of death included infection mostly due to sepsis, acute

chest syndrome (ACS), overt stroke, sudden during crisis and organ

damage due to hepatic or renal failure. Thirteen patients died of

unrelated causes mostly due to trauma.

In this work, survival analysis was performed using the risk of sub-distribution regression model.[9]

These models consider the cumulative incidence function, using a

weighting factor for each individual considering all outcomes. Thus,

the individual who suffers from the competing event is not censored

receiving a weight that decreases gradually with time.

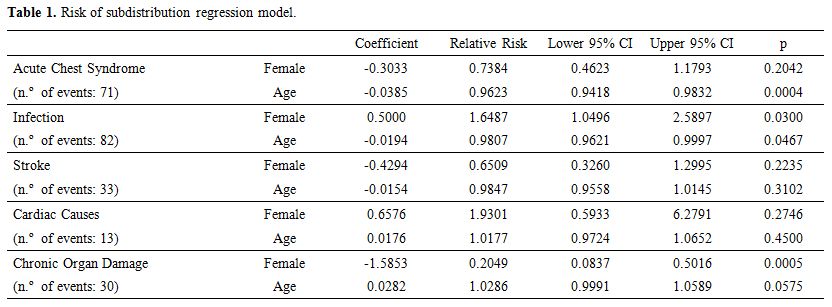

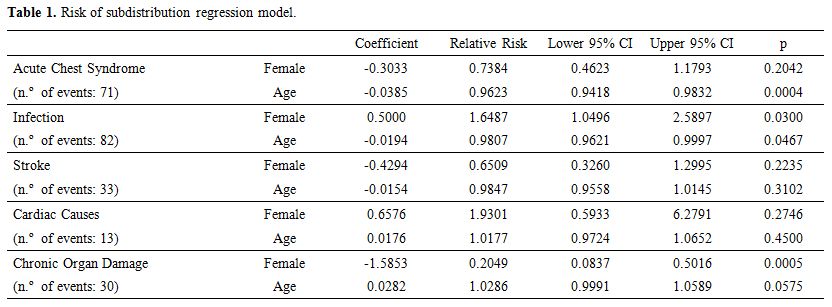

Eight models were implemented, one for each cause of death related to SCDA, as shown in Table 1:

Acute Chest Syndrome, Infection, Stroke, Cardiac Causes, Chronic Organ

Damage, Death During Crisis, Other (Splenic Sequestration, Hemolytic

Crisis or Hepatic Crisis) and Unknown.

|

Table 1. Risk of subdistribution regression model.

|

It is observed that

the males are most vulnerable for death from chronic organ damage (p =

0.0005) while females are most vulnerable for death from infection

(p=0.03). Sex did not show a statistically significant association with

other causes of death. Age is significantly (p ≤ 0.05) associated with

death due to ACS, infection, and death during crisis. The increase of

one year in age corresponds to a 3.8% reduction in the risk of death by

ACS; 1.9% in the risk of death from infection; and 6.2% for death

during crisis. On the other hand, the increase of one year in age

implies an increase of 2.8% in the risk of death from chronic organ

damage, at a significance level of 10%.

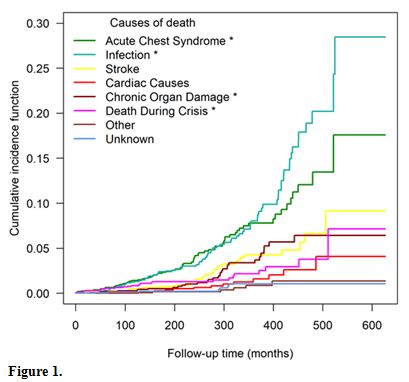

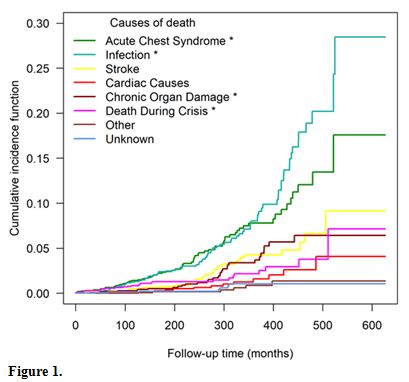

Figure 1

shows the cumulative incidence function, where one can observe that the

lower survival is related to death from infection, followed by death

due to ACS. Compared to the model of competing risks, the independent

variables age and sex were significantly associated with the outcomes

with an asterisk.

Analyses were performed with the use of packages “cmprsk”[13] and “mstate”[14-16] of R software.[17]

|

Figure 1 |

Discussion

Despite all Brazilian efforts, the mortality of patients with SCA is still very high in Brazil.[2,3]

These efforts included, among other things, newborn screening,

penicillin/antibiotic prophylaxis, vaccination including

anti-pneumococcus, anti-meningococcus, annual anti-influenza, blood

transfusion and transcranial doppler determinations.[3,5,18] In this study, we used the competitive risk analysis to evaluate the causes of mortality among our cohort.

A

competing risk is an event whose occurrence either precludes the

occurrence of another event under examination or fundamentally alters

the probability of occurrence of this other event, so it is an ideal

model to analyze causes of death in a specific disease with multiple

possible causes of death as in SCD.[6] It was used before in other chronic disease but never is SCD in Brazil before.[19]

The

competitive risk model was used because it is adequate in survival

analysis when there are mutually exclusive events, that is when the

occurrence of one event prevents another event occurring. In the

article, events are deaths from various causes. The cumulative

incidence function (represented by the graph) evaluates for each

patient the probability of occurrence of a specific event before a

certain time t. The risk sub-distribution model estimates the effect of

independent variables for each specific event, considering the presence

of competitive risks.

The reasons for the relatively low death

rate of females due to chronic organ damage are unknown. Possibilities

include gender differences in nitric oxide availability,[20] and the influence of the X-chromosome linked hemoglobin (Hb) F gene[21]

which may be protective against organ damage in females. However,

Dover’s et al. study was not confirmed by additional studies. In

addition, the increase in Hb F by the X-chromosome is minimal in

comparison to other studies indicating that Hb F has to be as high as ≥

8% to be effective. Other determinants of survival such as

hyperviscosity, alpha genotypes, and beta haplotypes could not be

determined at HEMORIO.

Conclusions

Mortality

among patients with SCD using the competing risks of death was

evaluated for the first time in a single institution in Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil.

In this article, we used the subdistribution hazard

function which evaluates the effect of covariates on the cumulative

incidence function for each of the competitive events. This modeling is

advantageous because it makes no assumption about the independence of

competitive events.

References

- Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, Abboud MR. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):311-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30193-9

- Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1510865

- Ballas SK. Sickle Cell Pain, 2nd Edition. Washington DC: International Association for the Study of Pain; 2014.

- Crowder M. Competing Risks. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2001. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420035902

- Lobo

CLC, Nascimento EMD, Jesus LJC, Freitas TG, Lugon JR, Ballas SK.

Mortality in children, adolescents and adults with sickle cell anemia

in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2018;40(1):37-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjhh.2017.09.006

- Gooley

TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure

probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations

of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695-706. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::AID-SIM60>3.0.CO;2-O

- Carvalho

M, S., Andreozzi V, L., Codeço C, T., Campos D, P., Barbosa M, T., S.,

Shimakura S, E. . Análise de sobrevivência: teoria e aplicações em

saúde. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2011.

- Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Hoboken: Wiley Interscience; 1980.

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496-509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144

- Cox

DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables (with discussion). Journal of the

Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1972;34(2):187-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1972.tb00899.x

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452

- Pintilie M. Competing Risks: A Practical Perspective. Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470870709

- Gray B. cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks. R package version 2.2-7. 2014.

- Putter

H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and

multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389-430. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2712 PMid:17031868

- de

Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. An R package for the analysis of

competing risks and multi-state models. J Stat Softw. 2011;38:1-30. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v038.i07

- de

Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. The mstate package for estimation and

prediction in non- and semi-parametric multi-state and competing risks

models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;99(3):261-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.001 PMid:20227129

- R

Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R

Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria2017 [Available

from: http://www.R-project.org

- Lobo

CL, Ballas SK, Domingos AC, Moura PG, do Nascimento EM, Cardoso GP, et

al. Newborn screening program for hemoglobinopathies in Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(1):34-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24711 PMid:24038856

- Baena-Diez

JM, Penafiel J, Subirana I, Ramos R, Elosua R, Marin-Ibanez A, et al.

Risk of Cause-Specific Death in Individuals With Diabetes: A Competing

Risks Analysis. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):1987-95. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0614 PMid:27493134

- Gladwin

MT, Schechter AN, Ognibene FP, Coles WA, Reiter CD, Schenke WH, et al.

Divergent nitric oxide bioavailability in men and women with sickle

cell disease. Circulation. 2003;107(2):271-8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000044943.12533.A8 PMid:12538427

- Dover

GJ, Smith KD, Chang YC, Purvis S, Mays A, Meyers DA, et al. Fetal

hemoglobin levels in sickle cell disease and normal individuals are

partially controlled by an X-linked gene located at Xp22.2. Blood.

1992;80(3):816-24. PMid:1379090

[TOP]