Given the lack of a standardized strategy for R/R AML and its disappointing prognosis, the enrollment in clinical trials is still considered the best option. Nonetheless, only a minority of patients can be recruited based on restrictive selection criteria and the enrollment of specialized centers. Chemotherapy-based salvage regimens are usually prescribed to patients with R/R AML. Most of the protocols include the combination of high doses of Cytarabine with other agents, such as anthracyclines, Etoposide, and nucleoside analogs. The most frequently administered combinations are Fludarabine, Cytarabine and Idarubicine (FLAI) or Mitoxantrone, Etoposide and Cytarabine (MEC). Recently, a systematic literature review showed a relatively high CR rate (44-60%), a short CR duration (5-10 months) and OS (6-9 months) in individuals exposed to standard chemotherapy protocols.[1]

The efficacy of the nucleoside analog Clofarabine has been assessed in patients with AML both in monotherapy and in combination, specifically with Cytarabine based on their synergistic action.[5] In particular, administration of Clofarabine with high doses of Cytarabine (CLARA) showed a CR rate of 44% and a mean OS of 6 months in R/R AML patients, together with a favorable safety profile.[6] In case of prescription of CLARA as a bridge to allogeneic transplantation, a median OS of 24 months and a 3-year OS of 55% can be achieved. Furthermore, CR can also be obtained in patients who were non-responders to Fludarabine-containing regimens.[7-8]

We retrospectively evaluated 47 and 22 patients with R/R AML consecutively exposed between 2001 and 2017 to second- and third-line therapy, respectively, in the Hematology units of the University Hospitals of Sassari and Cagliari. The aim of this observational study was to compare effectiveness, i.e., overall response rate (ORR), OS and relapse-free survival (RFS), and safety profile of CLARA and other standard chemotherapy protocols. In the cohort exposed to second-line therapy, 15 received CLARA and 32 different chemotherapy regimens (control group), whereas 7/22 and 15/22 were treated with CLARA or with other regimens in the cohort of the third-line therapy, respectively. No specific criteria were applied to select either CLARA or different therapeutic regimens, but all cases were discussed collegially taking into consideration previous lines of therapy and expected toxicities. All therapeutic approaches were allied with a primary intention to carry on with transplant after reaching CR. Dosages of Clofarabine in the CLARA regimen ranged from 22.5 to 40 mg/m2, followed 4 hours later by a dose of Cytarabine from 1 to 2 g/m2 for 5 days. The most frequently prescribed chemotherapy schemes in the control group were: Fludarabine-Cytarabine-based regimens with or without anthracycline (21 and 1 patients on second- and third-line therapy, respectively) and Cytarabine-anthracycline-Etoposide-based combinations (10 and 6 patients on second- and third-line therapy, respectively). Other less frequently administered regimens were based on Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, with or without chemotherapy (5 cases on third-line treatment). Comparisons between the groups mentioned above were carried out with chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests for qualitative variables and Student's t-test distribution or Mann-Whitney's tests for parametric and nonparametric variables. All analyses were performed with the statistical software Stata version 15 (StatsCorp, Texas).

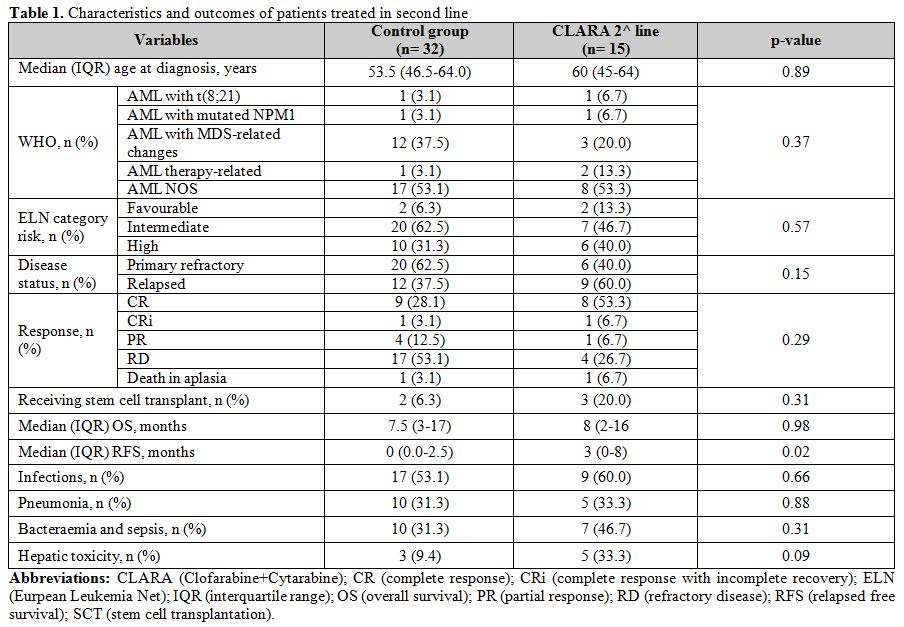

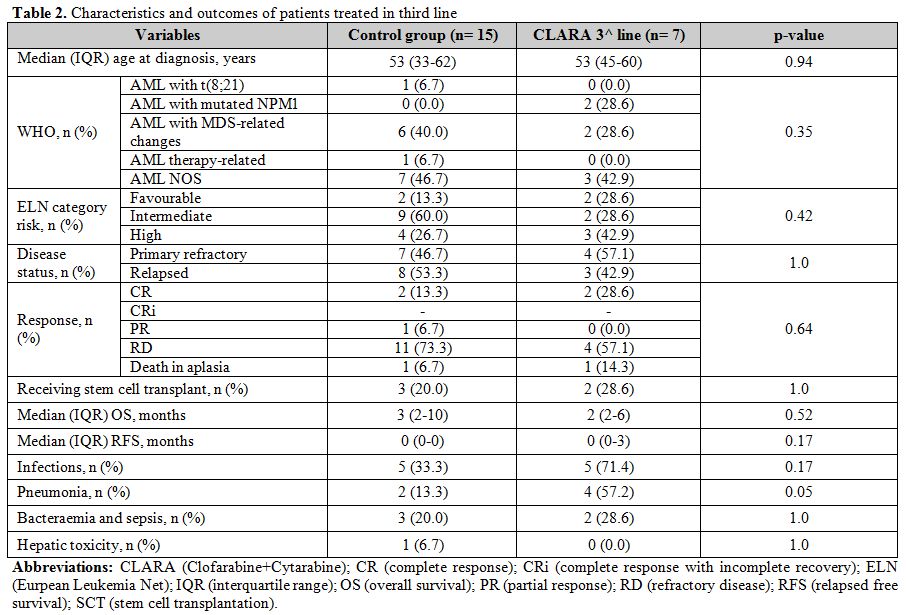

As shown in tables 1 and 2, the median (IQR) age of the entire cohort was 53 (33-64) years. According to the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, among patients treated in second line 25 patients (53%) had not otherwise specified AML (AML-NOS), 15 (32%) AML with myelodysplasia-related changes, 3 (6%) therapy-related AML, 2 (4%) AML with t(8;21) and 2 (4%) AML with NPM1 mutation. Among patients treated in third line 10 patients (45%) had AML-NOS, 8 (36%) AML with myelodysplasia-related changes, 1 (5%) therapy-related AML, 1 (5%) AML with t(8;21) and 2 (9%) AML with NPM1 mutation. According to the 2017 prognostic stratification by European Leukemia Net (ELN) 8 (12%), 38 (55%), and 23 (33%) patients were classified as at low, intermediate, and high-risk, respectively. Thirty-two (46%) had relapsed AML, whereas 37 (54%) had a primary refractory disease. No statistically significant differences were found between CLARA and control group according to age, WHO subtypes, ELN classification, and disease status in patients treated in both second and third line. We specifically evaluated the potential impact of latency between remission and relapse in each group, but no significant differences could be detected. In fact, in patients treated in second line median (IQR) lag between remission and relapse was 2 and 0 months in CLARA and control group (p-value: 0.60), respectively while in patients treated in the third line it was equal to 0 months in both groups ((p-value: 0.10).

|

Table 1. Characteristics and outcomes of patients treated in second line |

|

Table 2. Characteristics and outcomes of patients treated in third line |

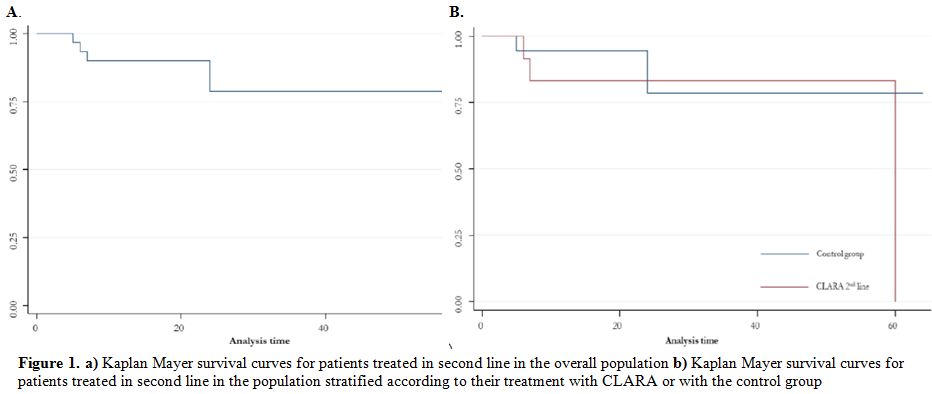

As shown in table 1, CR rate in the second-line therapy cohort was 53% and 28% in the CLARA and control (p-value: 0.09), respectively, while ORR was 67% and 44% (p-value: 0.14). Median OS was 8 and 7 months (p-value: 0.98) in the CLARA and the control group, respectively (figure 1); on the other side, median RFS was 3 and 0 months (p-value: 0.02), respectively. As shown in table 2, CR rate in the third-line therapy cohort was 29% and 13% in the CLARA and control (p-value: 0.57), respectively, while ORR was 29% and 20% (p-value: 1.0). Median OS was 2 and 3 months (p-value: 0.52), respectively. A median RFS of 0 was recorded in both groups. Patients who received allogeneic transplantation after second-line therapy were 20% and 6% in the CLARA and control group (p-value: 0.31), respectively while patients who received allogeneic transplantation after third-line therapy were 29% and 20% in the CLARA and control group (p-value: 1.00), respectively. Among the patients who underwent allogeneic SCT after second-line treatment, out the 2 treated within the control group one was in CR, and one in CR with incomplete recovery (CRi) whereas out the 3 treated with CLARA 2 were in CR and one in partial remission (PR). All of them achieved CR after transplant, and transplant-related mortality (TRM) was 0%. Among the patients who underwent allogeneic SCT after third-line treatment, out the 3 treated within the control group one was in CR, and two had a refractory disease (RD) whereas the 2 patients treated with CLARA were both in CR. Among the 3 patients treated within the control group, 2 achieved CR after transplant, and one still showed RD whereas among the 2 patients treated with CLARA one confirmed his CR while one died soon after transplant for TRM. Safety profile was good, with a tendentially higher rate of reversible (i.e., <2 weeks) hepatotoxicity cases after second-line therapy in the CLARA group (33% VS. 9%; p-value: 0.09) and a higher rate of pneumonia after third-line therapy in the CLARA group (57% VS. 13%; p-value: 0.05).

Comparison of our findings with those described in the literature showed that CR and OS rates were similar, whereas RFS was slightly lower in our cohort. Potential explanations could be the low percentage of patients exposed to chemotherapy as a bridge to allogeneic transplantation, as well as the retrospective design of our study which selected patients tendentially less fit than those described in prospective studies. Our data substantially confirm the potential effectiveness of CLARA in patients with R/R AML. In fact, even though a statistically significant improvement over other frequently prescribed salvage regimens was not demonstrated, our findings suggest a potential positive trend in terms of improvement in both CR, ORR, and RFS within a real-life setting. When considering that the main goal in R/R AML, regardless of salvage regimens, is to perform allogeneic transplantation as earliest as possible, CLARA may represent a valid option in this setting especially in patients with a contraindication for or resistant to anthracycline-containing regimens.