Nawfal R. Hussein1, Zana S.M. Saleema1 and Qais H. Abd2.

1 Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Duhok.

2 Kidney Disease Center, Duhok, Iraq.

Correspondence to: Dr. Nawfal R. Hussein, Department of Internal

Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Duhok, Duhok, Iraq.

Nawfal.hussein@yahoo.com

Published: May 1, 2019

Received: February 17, 2019

Accepted: April 12, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11(1): e2019034 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2019.034

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background Hepatitis

C virus (HCV) infection is a public health problem. Such an infection

is prevalent and aggressive in patients with end-stage kidney disease

(ESKD). The efficacy and the safety of direct-acting antivirus (DAA) in

patients with acute HCV and ESKD are under investigation. The aim of

this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of

sofosbuvir-containing regimens in this difficult-to-treat population.

Methods:

A prospective and observational study was conducted to evaluate the

efficacy and the safety of sofosbuvir containing regimen in patients

with ESKD who were undergoing haemodialysis and were acutely infected

with HCV. Subjects either received sofosbuvir 200 mg and daclatasvir 60

mg daily or sofosbuvir 400mg/ledipasvir 60mg daily for 12

weeks.

Results:

19 Patients were recruited in this study who were infected with HCV

genotype 1a. All subjects achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR)

twelve weeks after finishing the treatment course. No significant

adverse effects were reported, and the treatment course was well

tolerated.

Conclusions:

sofosbuvir-containing regimens were effective and safe for the

treatment of acute HCV in patients with ESKD who were on haemodialysis.

|

Introduction

Infection with HCV is a major public health issue with more than 70 million infected people around the world.[1]

The death toll for such a disease is more than 350,000 annually mainly

due to the complications of infection such as liver cirrhosis, hepatic

failure and hepatocellular carcinoma.[1]

The carcinogenesis of HCV is not fully understood.[2]

Although it is well known that HCV increases the risk of cancer through

a complex molecular pathway that involves an inflammatory process, it

is controversial that HCV plays a direct role in the development of

liver cancer.[2] Additionally, specific HCV genotypes

are associated with a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. In a

study conducted in the USA, HCV genotype 3 was shown to be associated

with a higher risk of cancer.[3] In addition, a study

conducted in Italy showed a significantly higher rate of HCV 1b

infection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.[4,5]

Risk

factors for HCV infections vary from a country to another. Unsafe

healthcare practice was the main cause of the spreading of this disease

in 2000.[1] The next mode of the transmission in the

low and middle-income countries is blood and blood products transfusion

due to the lack of blood donor screening.[1]

Additionally, the venous injection in drug abusers is a leading cause

of the spread of the virus in both developing and developed countries.

Patients with ESKD are at higher risk of HCV infection.[1,6] Although the spread of the virus in hemodialysis units is declining, the prevalence of HCV in such patients is still high.[7]

Previous studies showed that the prevalence of anti-HCV antibody

positivity among subjects with ESKD and on regular hemodialysis ranged

from 5% to 60%.[7] In a study conducted in Iraq, 5% of patients who were on dialysis were HCV positive.[8] Acute HCV infection is defined as the occurrence of its manifestation within six months of exposure.[9]

It can be defined as the presence of a positive HCV RNA with a

concurrent negative anti-HCV antibody level or a positive anti-HCV

antibody level after a prior negative anti-HCV antibody within the

previous six months,[9,10] With the availability of

DAA medications, the mainstream approach of treatment has shifted

obtaining a high sustained virologic response.[11] Previously, interferon was used for the treatment of acute HCV in some circumstances with significant side effects.[12] Otherwise, the treatment with DAA is associated with minor side effects and higher cure rates.[11]

Studies investigating the effectiveness of DAA in acute HCV are limited

and with small sample size. In one study, 20 patients were recruited,

and the sustained viral response (SVR) was achieved in all patients.[9]

One study was conducted to investigate the effectiveness of DAA in

patients with acute HCV and ESKD. Thirty-three patients, who were

infected with HCV genotype 1b and 2a were enrolled and were given

treatment for 24 weeks.[13] SVR was achieved in all patients without significant side effects.[13]

This study aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks

sofosbuvir-containing regimens in patients with ESKD who were infected

with acute HCV genotype 1a.

Methods

Patients and treatment.

In December 2017, an outbreak of HCV occurred in the dialysis unit in

Zakho city. In this dialysis unit, 40 ESKD patients were receiving

regular hemodialysis. Once the outbreak was established, the unit was

closed, and all patients were closely monitored for six months by

HCV-antibodies testing plus HCV real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Patients

diagnosed with HCV were directed to the infectious disease unit in

Azadi teaching hospital. Acute HCV infection was defined as a positive

HCV RT-PCR test in the setting of a concurrent negative HCV-antibodies

results or a positive HCV-antibodies result after a prior negative

result of HCV-antibodies within the past six months. We recruited

patients with the following criteria: patients with ESKD requiring

hemodialysis, positive for HCV RNA for less than six months and older

than 18 years old. Patients with acute renal failure were excluded.

ELISA and Biochemical tests.

The HCV-antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B

core IgG (HBcAb) and HIV Ab&Ag were investigated by ELISA kit

(DIA.PRO diagnostic Bioprobes, Italy) following the manufacturer’s

instruction. The detection of HCV and HIV was with a sensitivity (100%)

and specificity (100%), while the sensitivity and specificity of the

test for HBsAg were respectively 100% and 97.5%, according to the

manufacturer.

ALT, AST and serum albumin were measured by Cobas

chemistry analyzer (Roche). INR was estimated by START4 semiautomated

system (STAGO).

HCV quantification and genotyping.

In this study, the quantification of HCV was performed using Xpert HCV

quantification assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, the USA). Fresh

samples were kept at 4°C and tested within seventy-two hours after the

collection. One ml was added to a test cartridge, which was loaded into

a GeneXpert instrument. The linear range of the Xpert HCV assay is 10

IU/ml to 108 IU/ml. Results were

reported as follows: HCV present (with the associated quantitation

reported in IU per milliliter), or HCV was absent. All positive samples

were genotyped by reverse hybridization (NLM, Milan, Italy).

Results

Patients.

During the period between December 2017 and March 2018, 19 patients

were involved in the outbreak and were referred to our unit. Amongst

those, 12 were male and the average age of the patients was 54.8±13.6

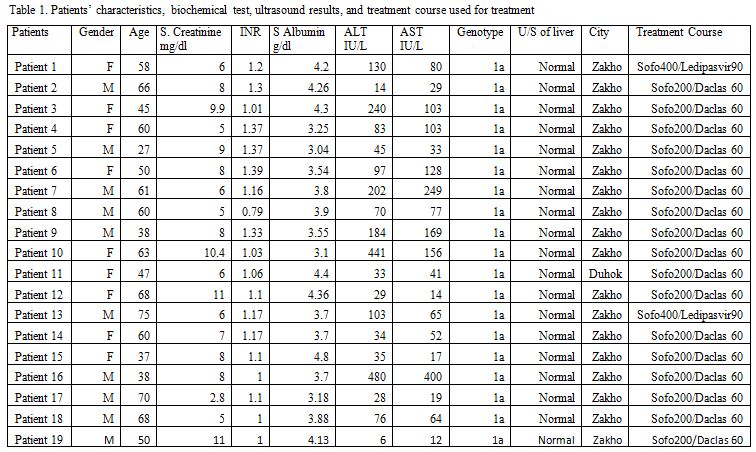

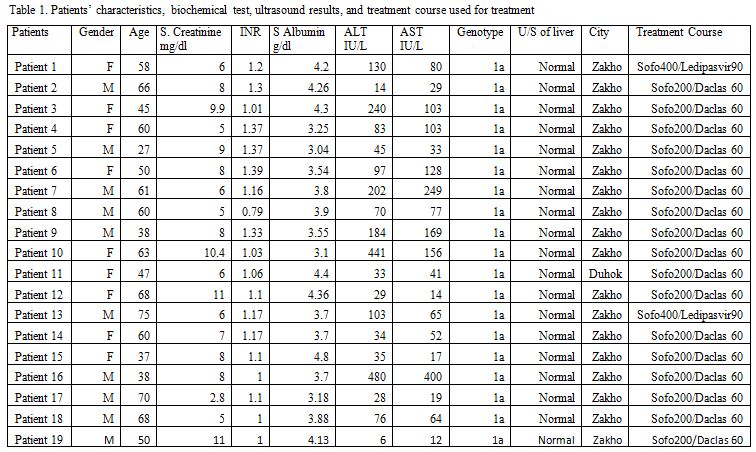

years (Table 1). All patients

involved in the outbreak were infected with HCV genotype 1a.

Additionally, all patients were negative for HIV and HBsAg. All

patients recruited in this study were treatment naive. The

investigation of the outbreak in the center showed that the mode of

transmission was an inappropriate medical procedure.

|

Table

1. Patients characteristics, biochemical test, ultrasound results, and treatment course used for treatment |

Treatment efficacy.

The primary end-point of this project was to investigate the proportion

of subjects who achieved SVR, which was defined as negative HCV RT-PCR

at twelve weeks after treatment. In our study, 17 patients received a

half dose of sofosbuvir (200 mg daily) after dialysis and a full dose

of daclatasvir (60 mg daily) for 12 weeks. Two patients received

sofosbuvir 400mg/ledipasvir 90mg fixed dose. The duration of treatment

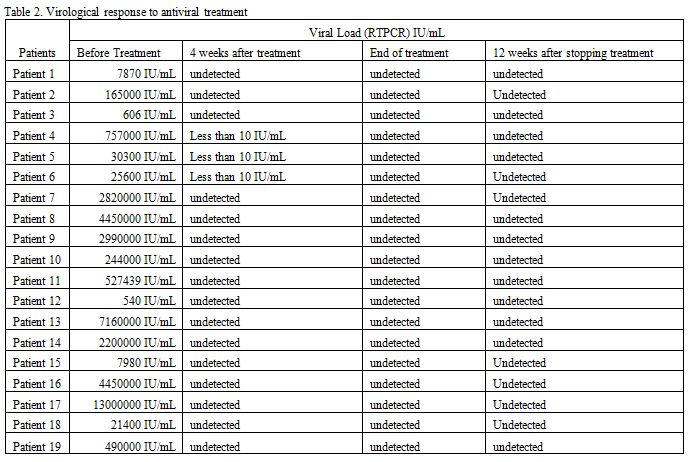

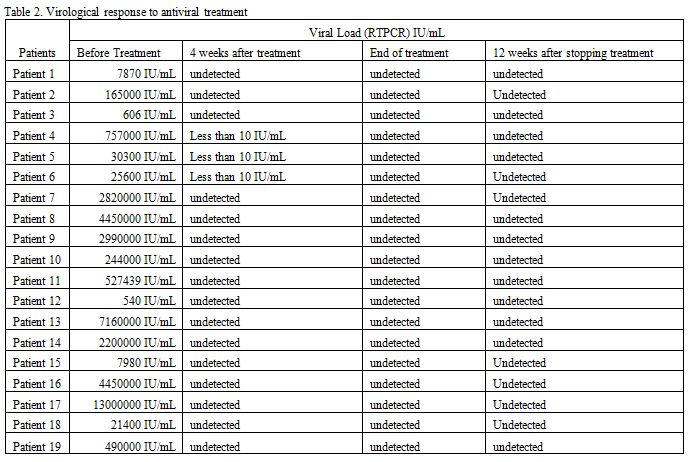

was for 12 weeks. The viral load became undetected in 16/19

(84.2%) patients after four weeks of treatment (Table 2). Sustained virologic response was achieved in all patients.

|

Table 2. Virological response to antiviral treatment |

Safety outcomes.

All subjects completed treatment the 12 weeks course and were followed

up for the following 12 weeks. The treatment course of acute HCV in

ESKD was well tolerated. During the study period, the most frequently

reported adverse effects were fatigue, anorexia, headache and dizziness. Discussion

International

guidelines do not provide an insight on how to choose the regimen,

timing, and duration of therapy for acute HCV. Additionally, no

useful guidance is provided for specific cases such as patients with

ESKD. Substantial uncertainty exists regarding the optimal treatment

regimen and duration of DDA in acute hepatitis. The 2016 American

Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)–Infectious Diseases

Society of America (IDSA) guidelines suggested “the same regimens for

acute HCV as recommended for chronic HCV infection … owing to high

efficacy and safety”, whereas the 2016 European Association for the

Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines recommended sofosbuvir–ledipasvir,

sofosbuvir–velpatasvir or sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir for 8 weeks in

acute HCV infection, with a longer duration of 12 weeks recommended for

those infected with HIV and/or baseline HCV RNA levels >1,000,000

IU/ml.[15] So, current international recommendations

for the treatment of acute HCV infection are controversial, and the

treatment of acute HCV infection could elaborate according the

circumstances, taking into account the baseline HCV RNA titres, the HCV

co-infections and the pre and on-treatment viral kinetics.[15]

The available studies of the treatment of acute HCV infection support

the use of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir for eight to twelve weeks.

Infection with HCV and its related complications are associated with a

significant rate of morbidity and mortality in patients with ESKD, due

to extrahepatic manifestations and especially to a glomerular

involvement.[16] One of the renal complications

related to HCV infection is membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

with or without cryoglobulinemia.[16] Additionally,

previous studies showed an association between HCV infection and

membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, fibrillary

or immunotactoid glomerulopathies, and thrombotic microangiopathy.[16]

Early treatment of HCV may prevent such complications and play a

significant role in a long-term comprehensive plan to eliminate the

infection by preventing the transmission in high risk groups such as

patients on regular dialysis.

DAA medications have

revolutionized the treatment of HCV infection. However, no data are

available on their effectiveness and safety in treating ESKD patients

with acute HCV. Our findings showed that a 12 weeks treatment course

with an interferon-free DAA resulted in a sustained virologic response

12 weeks after treatment in all patients with acute HCV genotype 1a

plus ESKD patients. The treatment course was not associated with

serious side effects related to the medications. The treatment course

was associated with rapid decline in the HCV-RNA levels in our

patients. In our study, cephid Xpert was used for HCV-RNA detection. In

three patients, the level of RNA was detectable but not quantifiable.

This was not associated with prior RNA levels. In a previous study

recruiting patients with acute HCV and EDKD recruiting patients with

HCV genotypes 1b and 2, all patients achieved SVR after receiving a

course of treatment for 24 weeks.[13] This is the

first study about the treatment of acute HCV in ESKD patients using 12

weeks course. Our findings are important for treatment plan as indicate

economic advantage by using half the dose of expensive sofosbuvir,

shorter period (12 weeks) and are important for public health as HCV

infection can be treated successfully and hence prevent further spread

of such an infection. The small sample size must not negate the

importance of the study as it showed promising results for the

treatment of infection and the prevention of further cases. The main

challenge in treating acute HCV is the diagnosis of such cases as the

vast majority of cases pass unnoticed. Our study has limitations.

We acknowledge that our study was not randomized and the analysis was

based upon the per-protocol population. However, we believe that

randomized project was considered to be extremely difficult when

dealing with such a public health problem.

Conclusions

In conclusion, DAA

containing sofosbuvir were suitable for the treatment of acute HCV

infection in patient with ESKD without major adverse events.References

- Petruzziello A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G,

Cozzolino A, Cacciapuoti C. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus

infection: An up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis

C virus genotypes. World Journal of Gastroenterology

2016;22(34):7824-7840. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7824 PMid:27678366 PMCid:PMC5016383

- Petruzziello

A. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. The Open Virology Journal

2018;12:26-32. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874357901812010026 PMid:29541276 PMCid:PMC5842386

- Kanwal

F, Kramer JR, Ilyas J, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. HCV genotype 3 is

associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular

cancer in a national sample of U.S. Veterans with HCV. Hepatology

(Baltimore, Md) 2014;60(1):98-105. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27095 PMid:24615981 PMCid:PMC4689301

- Petruzziello

A, Sabatino R, Loquercio G, Guzzo A, Di Capua L, Labonia F, Cozzolino

A, Azzaro R, Botti G. Nine-year distribution pattern of hepatitis C

virus (HCV) genotypes in Southern Italy. PLOS ONE 2019;14(2):e0212033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212033 PMid:30785909 PMCid:PMC6382136

- Petruzziello

A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G, Coppola N, Piccirillo M, Leongito M,

Azzaro R, Izzo F, Botti G. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) genotypes

distribution among hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Southern Italy:

a three year retrospective study. Infectious Agents and Cancer

2017;12(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-017-0162-5

- M.R.

Ibrahim N, Sidiq Mohammed Saleem Z, R Hussein N. The Prevalence of HIV,

HCV, and HBV Among Hemodialysis Patients Attending Duhok Hemodialysis

Center. Int J Infect 2018;5(1):e63246.

- Sohn

H-S, Kim JR, Ryu SY, Lee Y-J, Lee MJ, Min HJ, Lee J, Choi HY, Song YJ,

Ki M. Risk Factors for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection in Areas with

a High Prevalence of HCV in the Republic of Korea in 2013. Gut and

liver 2016;10(1):126-132. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14403 PMid:26260752 PMCid:PMC4694744

- Perico

N, Cattaneo D, Bikbov B, Remuzzi G. Hepatitis C Infection and Chronic

Renal Diseases. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

2009;4(1):207. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03710708 PMid:19129320

- Deterding

K, Spinner CD, Schott E, Welzel TM, Gerken G, Klinker H, Spengler U,

Wiegand J, zur Wiesch JS, Pathil A, Cornberg M, Umgelter A, Zallner C,

Zeuzem S, Papkalla A, Weber K, Hardtke S, von der Leyen H, Koch A,

von Witzendorff D, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir

fixed-dose combination for 6 weeks in patients with acute hepatitis C

virus genotype 1 monoinfection (HepNet Acute HCV IV): an open-label,

single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases

2017;17(2):215-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30408-X

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. Journal of Hepatology 2014;61(1):S58-S68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.012 PMid:25443346

- Hussein

NR. The Efficacy and Safety of Sofosbuvir-Containing Regimen in the

Treatment of HCV Infection in Patients with Haemoglobinopathy.

Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases

2017;9(1):e2017005. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2017.005 PMid:28105296 PMCid:PMC5224801

- Hussein

NR, Tunjel I, Basharat Z, Taha A, Irving W. The treatment of HCV in

patients with haemoglobinopathy in Kurdistan Region, Iraq: a single

centre experience. Epidemiology and Infection 2016;

144(8):1634-1640. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815003064 PMid:27125573

- He

YL, Yang SJ, Hu CH, Dong J, Gao H, Yan TT, Liu JF, Yang Y, Ren DF, Zhu

L, Zhao YR, Chen TY. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-based treatment

of acute hepatitis C in end-stage renal disease patients undergoing

haemodialysis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

2018;47(4):526-532. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14429 PMid:29250808

- Pawlotsky

J-M, Negro F, Aghemo A, Berenguer M, Dalgard O, Dusheiko G, Marra F,

Puoti M, Wedemeyer H. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C

2018. Journal of Hepatology 2018;69(2):461-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026 PMid:29650333

- Martinello

M, Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ, Matthews GV. Management of acute

HCV infection in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Nature

Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2018;15(7):412-424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0026-5 PMid:29773899

- Goel

A, Bhadauria DS, Aggarwal R. Hepatitis C virus infection and chronic

renal disease: A review. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology

2018;37(6):492-503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-018-0920-3 PMid:30560540

[TOP]