Tuysuz

G.1, Yildiz I.1,

Ozdemir N.1, Adaletli İ.2,

Kurugoglu S.2, Apak H.1,

Dervisoglu S.3, Bozkurt S.4

and Celkan T.1.

1

İstanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty Pediatric Hematology and

Oncology Dept.

2 İstanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty

Radiology Dept.

3 İstanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty

Pathology Dept.

4 Akdeniz University Medical Faculty Statistics

Dept.

Correspondence to:

Gulen Tuysuz. Istanbul University Cerrahpasa

Medical Faculty Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Dept. Adress: Koca

Mustafa Paşa Mahallesi, Cerrahpaşa Caddesi No:53, 34096

Fatih/İstanbul-TURKEY. Tel: +905053159667, Fax: +902126328633. E-mail:

gulentuysuz@hotmail.com

Published: May 1, 2019

Received: November 9, 2018

Accepted: April 17, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11(1): e2019035 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2019.035

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Objectives:

To review a single center outcome of patients with Langerhans Cell

Histiocytosis diagnosed at a tertiary referral hospital from Turkey.

Methods:

The files between 1989 and 2015 of 80 patients with LCH were

retrospectively analyzed.

Results:

During the 25 years, 80 patients were diagnosed with LCH. The median

age at diagnosis was 53 months (2-180 months) and the median follow-up

time of patients was 10 years and 9 months (24 months-25 years). Bone

was the most frequently affected organ (n:60, 75%). Initially, 43

patients (54%) had single system (SS) disease, 20 patients (25%) had

multisystem (MS) disease without risk organ involvement (MS-RO-), and

17 patients (21%) had a multisystem disease with risk-organ involvement

(MS-RO+). The overall survival (OS) rate was 91%, and event-free

survival (EFS) rate was 67% at 10 years. 10-year OS rate was lower for

patients with MS-RO+ (65%) when compared to those with, MS-RO-, and SS

(100%, 97%, p value=<0.001). The overall survival rate was also

lower in patients with lack of response to systemic chemotherapy on

12th week (p=<0.001), younger age (<2 years) at

presentation

(p=<0.02), skin involvement (<0.001) and lack of bone

lesions at

presentation (<0.001).

Discussion:

In the group with MS-RO+, OS is significantly low compared to other

groups. Further efforts are warranted to improve survival in MS-RO+

patients.

|

Introduction

Langerhans

cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare neoplasm caused by an abnormal

oligoclonal proliferation of Langerhans cells and their accumulation at

various tissues and organs.[1,2,3]

The overall incidence rate for LCH

was reported as 2.6 cases per million child years, and males are

affected to a higher degree than females.[4]

Langerhans cell

histiocytosis is categorized into two major categories based on the

extent of disease:[5] single-system

(SS) and multisystem (MS). The

clinical presentation and outcome of the disease are diverse, and

treatment options differ according to the extent and severity of

disease.[6-8]

In this article, we present a retrospective analysis

of LCH cases diagnosed at a tertiary referral hospital in Turkey over

the past 25 years. Our aim was to describe the course of the disease

and evaluate the factors that have an effect over survival in our

cohort.

Materials and Methods

The

data of patients with LCH, treated at Istanbul University, Cerrahpasa

Medical School Hospital Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Department

between 1989 and 2015, were retrospectively analyzed from the medical

records. A total of 80 patients were included. Their files were

reviewed for demographic characteristics, clinicopathological features,

laboratory findings, treatment regimens, and outcome.

Disease

staging and organ dysfunctions were evaluated by disease history,

physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Complete

blood count, liver and kidney function tests, serum electrolytes,

ferritin, total bilirubin, PT, a PTT, urine osmolality were checked in

all patients. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were performed only in

multisystem patients. The radiological examination included at least

chest X-ray and skeletal radiograph survey. Other further imaging

modalities such as ultrasonography, computerized tomography, magnetic

resonance imagining, bone scintigraphy, positron emission tomography

and pulmonary function tests were performed when evaluation of the

extent of disease was required.

LCH can be clinically be

classified in two general groups, single system and multisystem. Risk

organ involvement in the multisystem group is considered to be the most

aggressive form of the disease.[4,5]

While preparing the manuscript for

publication, patients were retrospectively staged according to

currently ongoing LCV IV trial of Histiocyte Society[9]

even though

different protocols have been used for classification and treatment of

these patients. According to LCH IV trial, in monosystemic (single

system) form, one organ or system is involved; such as bone (either as

a single bone; monosystem unifocal bone or more than one bone;

monosystem multifocal bone), skin or lymph nodes. In multisystemic form

two or more organs or systems are involved; either with or without risk

organs (hematopoietic system involvement, spleen and liver). Different

from the previous protocols, the lung is not considered as a risk organ

in LCH IV trial.

Treatment included local steroid therapy,

radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgical excision of the lesion (even

though it is not recommended any longer), or a combination of these

modalities. Depending on the year of admission, patients were treated

by DAL-HX 83 protocol[10,11,12]

between 1989 and 1991, LCH-1

protocol[12] between 1992 and

1996, LCH-II protocol[7] between

1996 and

2004 and LCH-III protocol[13]

after 2004.

For the evaluation of

response, the response criteria of LCH-1 Study[6]

were employed.

Responders had a complete resolution (NAD) or continuous regression of

disease; intermediate responders were patients with active disease who

had either stable disease or a mixed response (a regression of disease

but the appearance of new lesions in another site or organ system), and

non-responders had progression of the disease. Reactivation was defined

as a reappearance of disease signs or symptoms after complete disease

resolution.[11]

Statistics

Continuous

variables are presented as median (mean-max) deviation, while

categorical variables are given as percentages. The Shapiro Wilk test

was used to verify the normality of the distribution of continuous

variables. Statistical analysis of clinical characteristics between two

groups consisted of unpaired t-tests for parametric data and Mann

Whitney U test, whereas the chi-square/Fisher's exact tests were used

for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate

survival as a function of time, and the log-rank test analyzed survival

differences. Analyses were performed with PASW 18 (SPSS/IBM, Chicago,

IL, USA) software and two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Patient

Characteristics.

Among 80 eligible patients with LCH, 56 of them were male, and 24 were

female (M/F: 2.3). Median age at diagnosis was 36 months (2 months to

15 years). Patients in the SS group had a higher median age at

diagnosis when compared to MS-RO-

and MS-RO+

groups (p=0.01 and

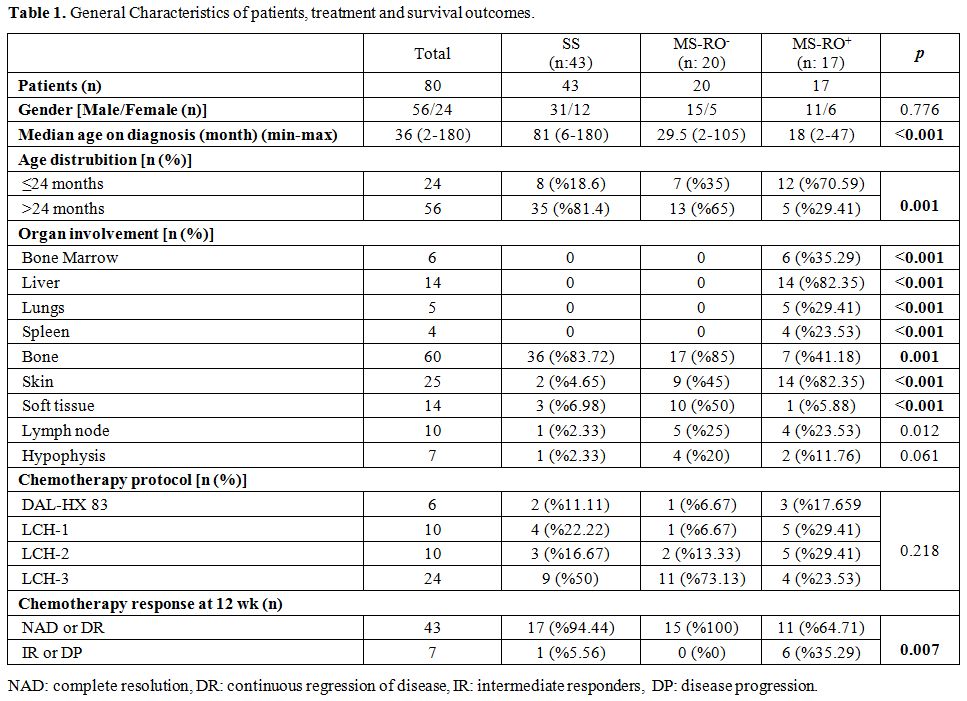

p=0.0001 respectively). General characteristics of patients are shown

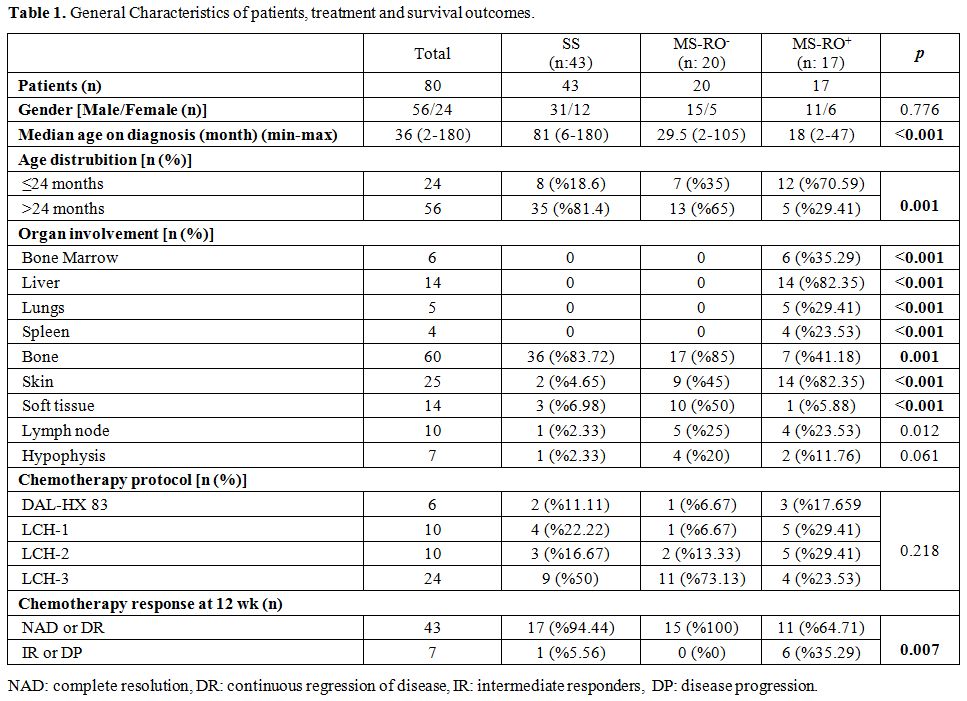

in Table 1.

|

Table

1. General Characteristics of patients, treatment and survival outcomes. |

Initial

symptoms.

At the time of diagnosis, swelling (n: 33, 41%) was the most recorded

referral symptom followed by pain (n: 24, 30%) in which 21 were related

to bone and 7 presented with limping gait. Skin rash or eruption was

noted in 16 (20%) of the patients while polyuria and polydipsia was the

presenting symptom in 7 (8.7%) of the patients.

Physical examination and organ involvement.

The most frequently affected organ was bone (n: 60, 75%). In MS-RO+

group, besides risk organ infiltration, skin involvement was also

statistically higher (n:14; p=0.0001) compared to the other two groups.

Bone involvement was statistically high in the SS group (n: 36;

p=0.01), and soft tissue involvement was statistically higher in MS-RO-

group (n:10; p=0.0001). Distribution of organ involvement varied

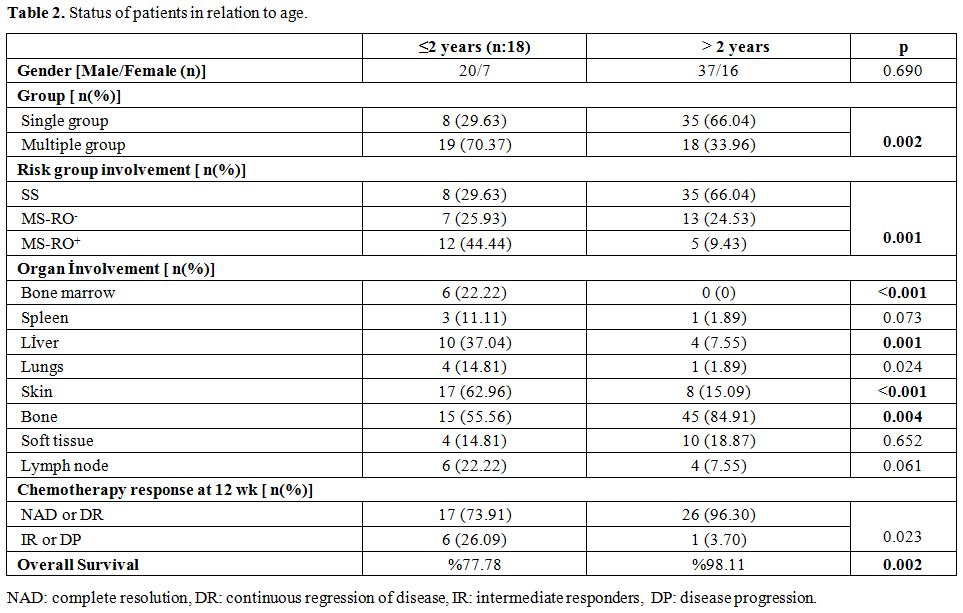

significantly by patient age. Status of patients according to age is

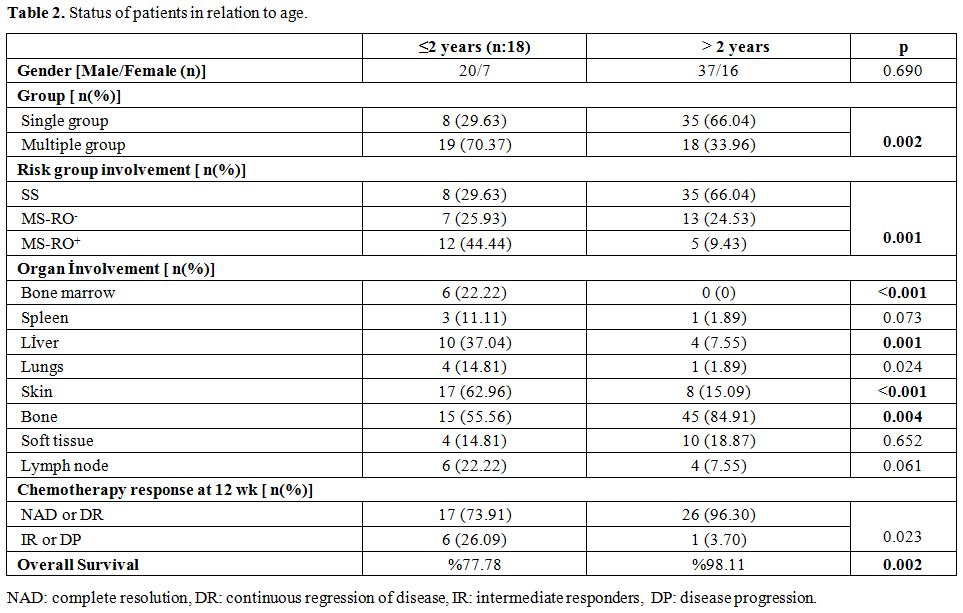

illustrated in Table 2.

|

Table

2. Status of patients in relation to age. |

Diagnosis.

Among 80 patients enrolled to study, 76 (95%) had a histological

diagnosis of LCH based on characteristics histological appearance of

LCH lesions on hematoxylin and eosin and positive immunohistochemical

staining with CD1a and/or S-100. The diagnosis was based on

radiological and clinical findings in 4 (5%) patients, because of the

surgical risk due to localization in the paravertebral area.

Staging.

Forty-three patients (53.75%) presented with SS disease and 37 patients

(46.25%) presented with multisystem disease. Distribution of risk

groups varied according to the age as is shown in Table 2.

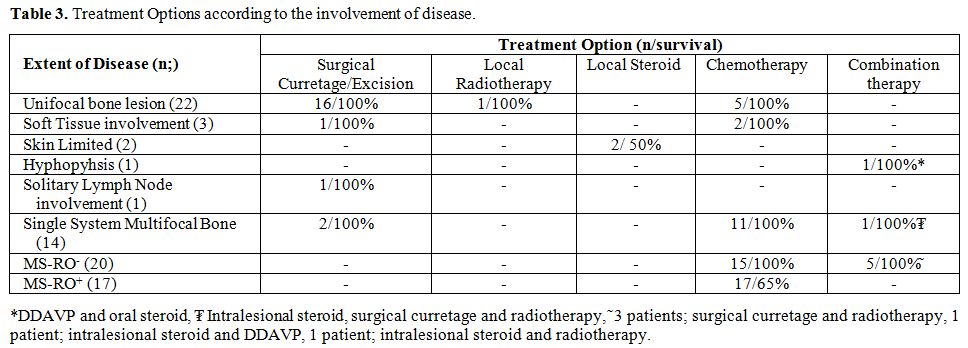

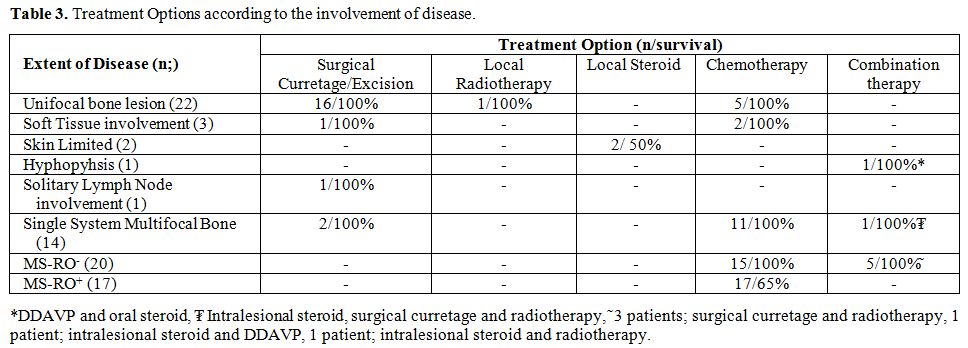

Treatment. Patients

were treated according to the extent of the disease. Details of

treatment regimens are illustrated in Table 3.

Among 22 patients with unifocal bone lesions 16 were treated with

surgical curettage/excision and the rest 6, who had involvement of

weight-bearing bones, skull base, temporal bones and vertebral column,

were treated with chemotherapy (n:5) and local radiotherapy (n:1). For

the patients in the multisystem low-risk group (n: 20), 15 were treated

with chemotherapy, and the rest 5 were treated with combination

treatments. All patients in the multisystem high risk group (n: 17)

were treated with systemic chemotherapy. A total of 50 patients from

all groups received chemotherapy as the treatment. According to

chemotherapy response on week 12, 43 patients (86%) were classified as

responders; of these, 33 (66%) had NAD, and 10 (20%) had DR. Seven

patients (14%) were evaluated as non-responders; of these 3 (6%) had IR

and 4 (8%) had DP. Chemotherapy response was statistically worse in

MS-RO+

group compared to the other two groups (p=0.007) and in patients, under

2 years of age (p=0.023) as is shown in Table 1 and 2.

|

Table

3. Treatment Options according to the involvement of disease. |

Treatment

response and outcome.

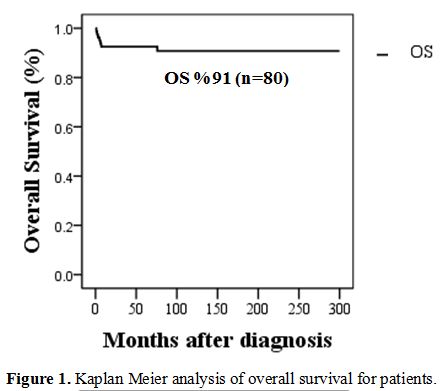

The median follow up time was 10 years and 9 months (1 month to 25

years), 10-year overall survival (OS) rate in the entire patient cohort

were 91.25 %, and EFS (event-free survival) rate was 67.5%. Seven

patients died. One patient in the single system group (skin

involvement) has developed reactivation of risk organ involvement

during follow up and was lost due to progressive disease. Besides this

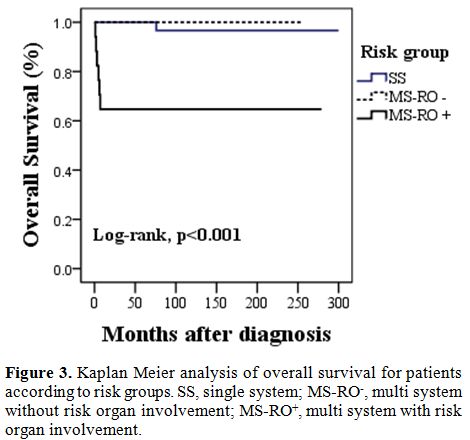

patient, the rest 6 were in MS-RO+ group. 10-year

OS rate was lower for patients with MS-RO+

(65%) when compared to those with, MS-RO-,

and SS (100%, 97%, p value=<0.001).

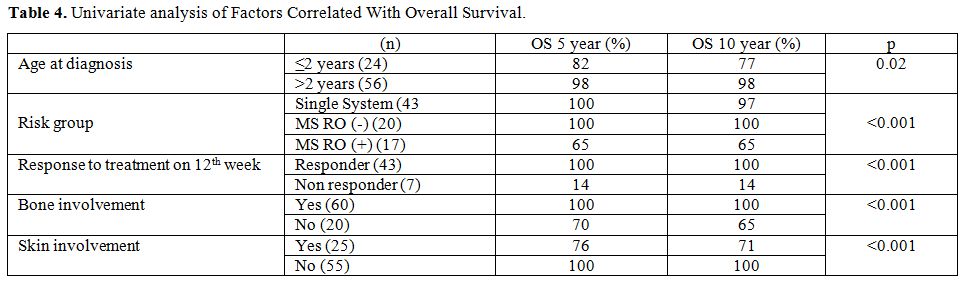

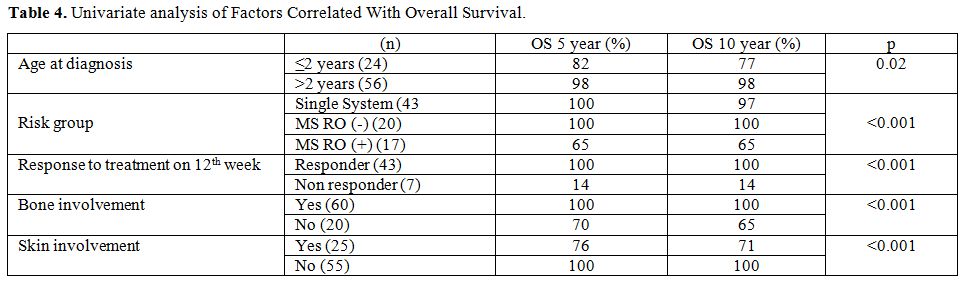

Regarding

the age of patients' OS rate at 10 years from diagnosis was 77% for

patients younger than 2 years of age and 98% for patients older than 2

years of age (p=0.02). Bone involvement was reported in 60 patients

(75%). Ten year OS rate was significantly higher in patients with bone

involvement than in those with extraosseous disease site involvement

(100% vs. 65%; p=<0.001). Even among patients of MS-RO+

group, presence of bone lesions was associated with better OS (%100 vs.

% 40; p=0.016). Ten year OS rate was significantly higher in patients

who responded to initial treatment at 12 weeks compared to those who

did not (100% vs. 14%; p=<0.001) and also in patients with skin

involvement as is shown in Table

4. Due to the difference in the distribution of deaths

among groups, we could not perform multivariate analysis.

|

Table

4. Univariate analysis of Factors Correlated With Overall

Survival. |

Reactivation.

Out of 80 patients, 20 (25%) experienced at least one reactivation. The

first reactivation occurred 2-46 months (median: 11 mo) after the

initial diagnosis. Regarding the timing, one patient (5%) reactivated

during induction treatment, 4 (20%) patients reactivated during

continuation treatment and 15 patients (75%) reactivated while on

follow up. Among these reactivations, 4 occurred in the first year and

the rest 11 afterward (2-46 months, median: 17 months after the initial

diagnose). Among the patients with first reactivation, 7 patients had

SS MFB, 6 patients had SS SS (single system, single side), 4 patients

had MS-RO+,

and 3 patients had MS-RO-

disease. The most clinical pattern of reactivation was limited to the

bone. Bone reactivation was observed in 16 of the 20 patients (7

patients unifocal, 4 patients multifocal bone and in 5 patients

reactivation was associated with other organs' involvement). Risk organ

reactivation was observed in only 3 patients (15%). Patients with

reactivated disease were treated with chemotherapy (n:17), or local

therapy (radiotherapy (n:1), curettage (n:1) and intralesional steroid

(n:1). Five patients experienced multiple reactivations: one patient

experienced 2, three patients experienced 3, and one patient

experienced 4 reactivations in the follow-up; within a mean period of

17 (9-26 mo) months. The 10-year reactivation rates for SS-SS, MS-RO-, and MS-RO+

patients were 30%, 15%, and 23.5% respectively. Reactivation rate did

not differ statistically according to the involved organs or risk

groups. Reactivation did not affect mortality except for one patient in

group SS-SS (MFB) who relapsed in follow-up with risk-organ involvement

and died due to disease progression despite the combined chemotherapy

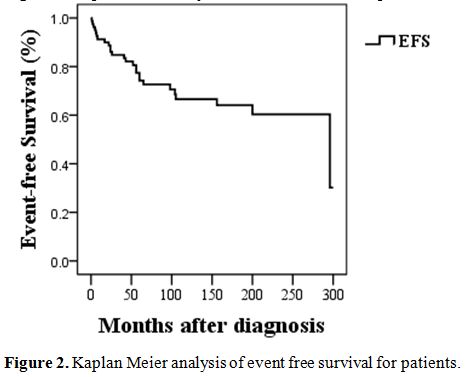

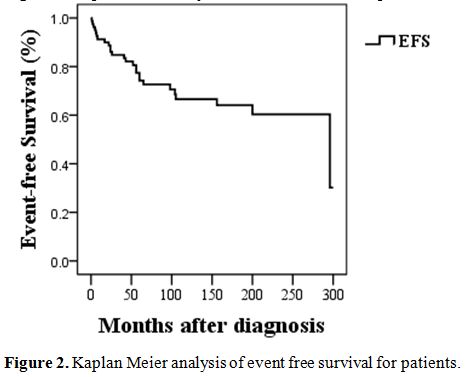

protocols in 6 months. The EFS of the cohort is shown in Figure 2.

|

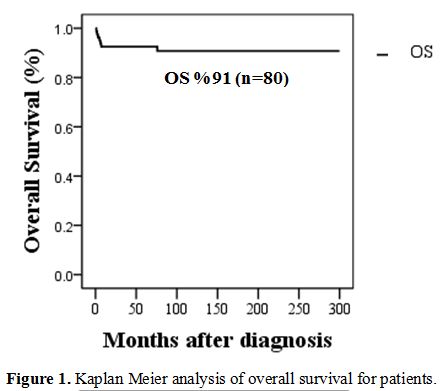

Figure 1. Kaplan

Meier analysis of overall survival for patients. |

|

Figure

2. Kaplan Meier analysis of event free survival for patients. |

|

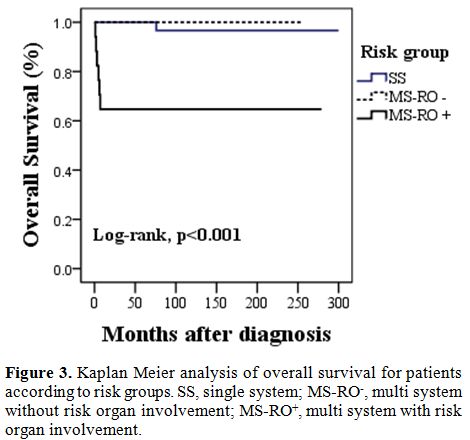

Figure

3. Kaplan Meier

analysis of overall survival for patients according to risk groups. SS,

single system; MS-RO-, multi system without risk organ involvement;

MS-RO+, multi system with risk organ involvement. |

Discussion

Because

LCH is a rare disease, disease-related publications in the literature

are usually multi-institutional. This report is one of the rare

single-center studies within 25 years including 80 pediatric patients

with sufficient follow up duration. Our aim was to describe the course

of the disease and evaluate the outcomes.

The demographic features

of LCH patients in our cohort were comparable with previous reports

showing early onset of disease and male predominance.[14,15]

The median age of our patients at diagnosis was 36 months; more than

1/3 of patients were under 2 years, and the male/female ratio was 2.3.

In

concordance with previous reports, the majority of our patients

presented with symptoms related to bone (71%) including swelling, pain

and limping gait.[16,17,18] The

most affected organs

by disease in our study after bone were skin, soft tissue and liver

retrospectively and which was also in line with the previously reported

series in the literature.[17,18]

Presence of bone lesions at diagnosis was associated with better OS in

our cohort as was described in the literature before.[19,20]

Even among MS-RO+

group, OS was significantly better in patients with bone disease (%100

in the presence of bone disease and 40% in the absence of bone disease;

p=0.016). Even though this is in concordance with previous reports

showing the favorable course of patients with bone involvement among

MS-RO+ patients, in

our opinion, our number of patients is too low (n:17) to contribute to

this hypothesis.[20]

In

our cohort, group involvement differed according to age, while the

children older than 2 years mostly presented with SS disease and bone

involvement, the younger group (≤2 years of age) presented with more

multisystem disease, skin and risk organ involvement. This was in

concordance with previous studies in the literature.[16,17,19]

Kim

et al. described "bone" as the most common site of involvement in their

study among the patients between 1 to 5 years of age.[16,21]

In 2012, Postini et al. reported their 40 years of experience with

pediatric LCH patients. Single system unifocal bone involvement was the

most observed clinical presentation in patients over 2 years of age.[20,22]

In a nationwide survey from Korea, young age at diagnosis (<2

years)

was associated with multisystem risk organ involvement resulting in

higher mortality.[16]

In LCH, the course of the

disease is highly heterogeneous and it is related to the extent of

organ involvement. In 2014, Lee at al reported the outcome of 22 years’

experience. The OS rate was significantly low in patients with

risk-organ involvement.[21] In the

study by Yagci et

al. where the outcome of 217 LCH patients was described OS and EFS

rates were significantly worse in MS-RO+.[17] In our study, patients with SS

disease and MS-RO-

had excellent survival rates. All patients except one survived in these

two groups. The only patient dead was a boy who had a reactivation of

risk organ involvement during follow up. Besides this patient, all the

other deaths were observed in the MS-RO+. Our findings

support the hypothesis that risk organ involvement is a strong negative

predictor of outcome in LCH patients.

Skin involvement was observed in 25 (31%) of our cohort. Age<2

years and MS-RO+ were

associated with skin involvement (p<0.001) as was shown in the

literature before.[21] Several

studies revealed the presence of somatic BRAF-V600E mutation on skin

biopsy.[23,24] The existence of

BRAF-V600E in circulating blood has been associated with disease

recurrence.[25]

In our cohort, a skin biopsy or peripheral blood were not available for

analyses of BRAF-V600E mutation. However, in univariate analyses

patients with skin involvement had lower EFS and OS. Due to the close

association of skin disease with risk-organ involvement and the low

number of patients enrolled we cannot conclude whether skin involvement

is an independent predictor of poor outcome. Prospective multicenter

trials are needed to determine the effect of skin involvement over the

outcome in LCH patients.

There is no current standard management

protocol for patients whose disease is unresponsive to frontline

therapy or who present with multiple reactivations. Even though

patients with single bone or low-risk multisystem reactivation respond

well to second-line treatments such as 6-mercaptopurine and

methotrexate, patients with risk-organ reactivation have inadequate

response even to salvage protocols. Treatment of refractory LCH

patients with 2CdA as monotherapy has shown a higher response rate in

patients with non-risk organs involvement, but limited activity in

refractory patients with risk-organ involvement.[26]

Combination of 2CdA with Cytarabine (Ara-C) as a salvage protocol has

promising results.[27] Even in the

MS-RO+ group, 5 year

survival rate was reported to be 85% in the phase II study by Donadeiu

et al.[28] The principal declared

side effect of this treatment was severe hematologic toxicity and

arising severe infection.[28]

Currently, ongoing prospective LCH-IV study is evaluating the effect of

2CdA and Ara-C combination chemotherapy for risk organ involved

refractory LCH patients.[9,27] In

our cohort we treated 2 of our patients with a combination of 2CdA and

Ara-C; one was a girl with single system bone involvement who relapsed

during maintenance therapy from multiple bones. She achieved remission

with 2CdA treatment until now. The second patient was initially staged

in single system group (skin involvement) but had reactivation of risk

organ involvement during follow up. He died because of progressive

disease despite 2CdA treatment. In our study, the number of patients

was too few to report 2CdA efficiency. In the literature, some case

reports are showing the efficacy of Clofarabine as monotherapy in

refractory LCH patients.[26]

Rodriguez-Galindo et al.

showed complete remission in 2 refractory LCH patients (both without

risk organ involvement) with Clofarabine therapy who were unresponsive

to 2-CdA treatment.[29] This

finding was in

concordance with the recent study showing the superiority of

Clofarabine treatment in non-risk organ involved refractory LCH

patients.[30]

There are also promising reports regarding the Lenalidomide plus

steroid treatment in refractory patients.[31,32]

The main advantage of this protocol is the feasibility of treatment at

an outpatient clinic, cost-affectivity of the drug and reported limited

toxicity. However, literature regarding this protocol is scarce in the

pediatric population.

After the description of recurrent oncogenic

mutations affecting the MAPK pathway in LCH patients, targeted

therapies such as BRAF, MEK or BRAF/MEK inhibitors were reported to be

useful for patients with these mutations who even were unresponsive to

salvage treatments.[22,33,34]

However, further studies are warranted to reveal the efficacy, safety,

and long term outcome in the pediatric population for targeted

therapies.

Reactivation is a common problem in the treatment of patients with LCH.[18,20,21]

The total reactivation rate in our cohort was 25%. This rate is similar

to the reported data.[16,20,25]

Reactivations predominantly affected the bones as was shown in the

literature before.[19,20]

Even in the group with multifocal bone involvement or in patients with

multiple reactivations, recurrence or the disease, were not associated

with mortality. Only one patient with MS-RO+

reactivation died despite rescue treatment, which suggests the severity

of risk organ involvement also in disease reactivation. The 5-year

reactivation rates of our patients did not differ between the groups,

which was contradictory to the previous reports in where higher

reactivation rates were reported in the MS group.[16]

In our opinion, this is related to poor outcome in MS-RO+

group. Because most of these patients (5 of 6) could not get into

remission, they died in early stages of treatment before developing any

reactivation.

Conclusions

In conclusion,

our study shows favorable disease course in SS and MS-RO-

groups in LCH patients. Patients within these groups, survive with

chemotherapy, even if they develop multiple reactivations. Risk organ

involvement, younger age at presentation (<2 years),

unresponsive to

induction treatment, skin involvement, and absence of bone involvement

at diagnosis remained subgroups of worse outcome in our cohort. Further

improvement with more potent agents especially during induction is

warranted for the treatment of this group.

References

- Willman CL, Busque L,

Griffith BB, et al.

Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X)-a clonal proliferative

disease. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 154-160. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199407213310303

PMid:8008029

- Nezelof

C, Basset F. An hypothesis Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the failure

of the immune system to switch from an innate to an adaptive mode.

Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 42: 398-400 https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.10463

PMid:15049008

- Grois

N, Potschger U, Prosch H, et al. Risk factors for diabetes insipidus in

Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2006; 46: 228-233https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20425.

PMid:16047354

- Alston

RD, Tatevossian RG, McNally RJ, et al. Incidence and survival of

childhood LCH in northwest England from 1954 to 1998. Pediatr Blood

Cancer 2007; 48: 555-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20884

PMid:16652350

- Haupt

R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al.; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans

cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up,

and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood

Cancer 2013; 60: 175-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24367

PMid:23109216 PMCid:PMC4557042

- Gadner

H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of

treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr

2001; 138: 728-34. https://doi.org/10.1067/mpd.2001.111331

PMid:11343051

- Gadner

H, Grois N, Pötschger U, et al; Histiocyte Society. Improved outcome in

multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis is associated with therapy

intensification. Blood 2008; 111: 2556-62. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-08-106211

PMid:18089850

- Kudo

K, Ohga S, Morimoto A, et al. Improved outcome of refractory Langerhans

cell histiocytosis in children with hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation in Japan. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010; 45: 901-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.245

PMid:19767778

- LCH-IV,

International Colloborative Treatment Protocol for Children and

Adolescents with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Amended protocol

version 1.3 Nov 25. 2015.

- Gadner H,

Heitger A, Grois N, et al. Treatment strategy for disseminated

Langerhans cell histiocytosis. DAL HX-83 Study Group. Med Pediatr Oncol

1994; 23: 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpo.2950230203

PMid:8202045

- Minkov

M, Grois N, Heitger A, et al. Treatment of multisystem Langerhans cell

histiocytosis. Results of the DAL-HX 83 and DAL-HX 90 studies. DAL-HX

Study Group. Klin Padiat 2000; 212: 139-44. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2000-9667

PMid:10994540

- S.

Ladisch and H. Gadner. Treatment of Langerhans cell

histiocytosis--evolution and current approaches. Br J Cancer Suppl

1994; 23: 41-6.

- Ramzan M, Yadav SP.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as isolated mediastinal mass

in an infant. Indian Pediatr 2014; 51: 397-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-014-0405-0

PMid:24953585

- Martin

A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, Carachi R. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23

years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae.

Scott Med J 2014; 59: 149-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036933014542387

PMid:24996784

- Babeto

LT, de Oliveira BM, de Castro LP, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis:

37 cases in a single brazilian institution. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter

2011; 33: 353-7. https://doi.org/10.5581/1516-8484.20110098

PMid:23049339 PMCid:PMC3415777

- Kim

BE, Koh KN, Suh JK, et al; Korea Histiocytosis Working Party.Clinical

features and treatment outcomes of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a

nationwide survey from Korea histiocytosis working party. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol 2014; 36: 125-33. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000054

PMid:24276037

- Yağci

B, Varan A, Cağlar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis:

retrospective analysis of 217 cases in a single center. Pediatr Hematol

Oncol 2008; 25: 399-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/08880010802107356

PMid:18569842

- Sedky

MS, Rahman HA, Moussa E, et al. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) in

Egyptian Children: Does Reactivation Affect the Outcome? Indian J

Pediatr 2016; 83: 214-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-015-1801-8

- A

multicentre retrospective survey of Langerhans' cell histiocytosis: 348

cases observed between 1983 and 1993. The French Langerhans' Cell

Histiocytosis Study Group. Arch Dis Child 1996; 75: 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.75.1.17

- Aricò

M, Astigarraga I, Braier J, et al; Histiocyte Society. Lack of bone

lesions at diagnosis is associated with inferior outcome in multisystem

langerhans cell histiocytosis of childhood. Br J Haematol 2015;169:

241-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13271

PMid:25522229

- Lee

JW, Shin HY, Kang HJ, Kim H, et al. Clinical characteristics and

treatment outcome of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 22 years'

experience of 154 patients at a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol

2014; 31: 293-302. https://doi.org/10.3109/08880018.2013.865095

PMid:24397251

- Postini

AM, del Prever AB, Pagano M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 40

years' experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 34: 353-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318257a6ea

PMid:22627580

- Morren

MA, Vanden Broecke K, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse Cutaneous

Presentations of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children: A

Retrospective Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016; 63: 486-92. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25834

PMid:26586230

- Badalian-Very

G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans

cell histiocytosis. Blood 2010; 116: 1919-23. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

PMid:20519626 PMCid:PMC3173987

- Berres

ML, Lim KP, Peters T, Price J, et al. BRAF-V600E expression in

precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically

distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med 2014; 211: 669-83. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20130977

PMid:24638167 PMCid:PMC3978272

- Weitzman

S, Braier J, Donadieu J, Egeler RM, Grois N, Ladisch S, Pötschger U,

Webb D, Whitlock J, Arceci RJ. 2'-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA) as

salvage therapy for Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). results of the

LCH-S-98 protocol of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;

53: 1271-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22229

PMid:19731321

- Rigaud

C, Barkaoui MA, Thomas C, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis:

therapeutic strategy and outcome in a 30-year nationwide cohort of 1478

patients under 18 years of age. Br J Haematol 2016;174: 887-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14140

PMid:27273725

- Donadieu

J, Bernard F, van Noesel M, et al. Cladribine and cytarabine in

refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: results of an

international phase 2 study. Blood 2015; 126: 1415-23. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-03-635151

PMid:26194764 PMCid:PMC4624454

- Rodriguez-Galindo

C, Jeng M, Khuu P, McCarville MB, Jeha S. Clofarabine in refractory

Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008; 51: 703-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21668

PMid:18623218

- Simko

SJ, Tran HD, Jones J, Bilgi M, Beaupin LK, Coulter D, Garrington T,

McCavit TL, Moore C, Rivera-Ortegón F, Shaffer L, Stork L, Turcotte L,

Welsh EC, Hicks MJ, McClain KL, Allen CE. Clofarabine salvage therapy

in refractory multifocal histiocytic disorders, including Langerhans

cell histiocytosis, juvenile xanthogranuloma and Rosai-Dorfman disease.

Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014; 61: 479-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24772

PMid:24106153 PMCid:PMC4474604

- Uppuluri

R, Ramachandrakurup S, Subburaj D, Bakane A, Raj R. Excellent remission

rates with limited toxicity in relapsed/refractory Langerhans cell

histiocytosis with pulse dexamethasone and lenalidomide in children.

Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017; 64: 110-2. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26199

PMid:27555565

- Uppuluri

R, Ramachandrakurup S, Balaji R, Subburaj D, Bakane A, Raj R.

Successful Treatment of Refractory Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the

Choroid Plexus in a Child With Pulse Dexamethasone and Lenalidomide. J

Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017; 39: 74-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000735

PMid:28099396

- Heisig

A, Sörensen J, Zimmermann SY, Schöning S, Schwabe D, Kvasnicka,

Raphaela Schwentner HM, Hutter C, and Lehrnbecher T. Vemurafenib in

Langerhans cell histiocytosis: report of a pediatric patient and review

of the literature. Oncotarget 2018; 9: 22236-40. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25277

PMid:29774135 PMCid:PMC5955145

- Awada

G, Seremet T, Fostier K, Everaert H, and Neyns B. Long-term disease

control of Langerhans cell histiocytosis using combined BRAF and MEK

inhibition. Blood Adv 2018; 2: 2156-8. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018021782

PMid:30154124 PMCid:PMC6113614

[TOP]