International travelers visiting endemic malaria countries are at increased risk of contracting the disease. Due to the increased air travel in terms of networks and improved global air connectivity, the risk of importing infections has increased dramatically.[2-7]

The association of malaria risk with international air travel in endemic countries has been certainly established. This risk varies depending upon various factors such as the degree of endemicity of the area visited, length of stay, baseline health condition of the individual, preventive measures employed and the general behavior, etc.[5,7] Chen et al. have observed a significant association between the trip's duration and health risks.[7] Furthermore, the global increase in travel has significantly contributed to the importation of Anopheles mosquitoes, mostly from Africa.[6]

The population studied has been composed mostly by tourists or people traveling for business, which is a heterogeneous population with very different behavior, particularly in adopting preventive measures.[5,7] On the other hand, there are no accepted guidelines for travelers in endemic regions.[8,9] Airline cabin crew traveling to malaria-endemic countries are a worker category, particularly vulnerable, as the nature of their work demands multiple short stays or layovers in these countries, and contemporary could show a great awareness of the risk and then the possibility of preventive measures.[10-12] However, limited data are available about occupational malaria risk among cabin crewmembers.[10,12] A comprehensive article by Byrn[10] was able to quantify the annual risk of falciparum malaria among nonimmune, UK-based airline crew and to undertake a risk assessment of short layovers in sub-Saharan African cities. The annual risk of falciparum malaria was calculated to be 1.6 cases per 100,000 nights of exposure (95% CI0.5–3.7). The crew reported widespread use of personal protection measures during the evenings when at risk. Attack rates of falciparum malaria were considerably lower than those reported in tourists during visits to sub-Saharan Africa. Factors contributing to this low attack rate included risk awareness, a protected sleeping environment, an urban setting, vector environmental controls, brief exposure, and good compliance with personal protection measures. Previously reported chemoprophylaxis compliance of < 10% in the same population was unlikely to have contributed to the low rate of disease.

Another important report was made by Selen et al.[11] in 2012. Their article assessed the malaria prevention knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of an important American Airline crew members to provide information for potential interventions. Overall, flight attendants (FA) and pilots demonstrated a good knowledge of malaria prevention, but many performed risky activities while practicing only some recommended malaria preventive measures. However, less than half in both groups always used insect repellents (46% FA, 47% pilots). Many respondents were unaware of how to get antimalarial medications (52% FA, 30% pilots) and were concerned about their side effects (61% FA, 31% pilots). However, airlines do not have a common program of education in this field, so this report cannot be generalized.

Concerned by the high and rising increase of imported case of malaria in Qatar, we acquired the knowledge, awareness, and practices about malaria among the staff of an awarded commercial airline, having as principal layover Doha International Airport.

In the present cross-sectional study, 40 cabin-crew members, who frequently travel to malaria-endemic areas, were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to collect demographic profile and knowledge about malaria. A survey, containing both closed and open-ended questions, was given to participants via the receptionists at the medical center of the airline. The level of their awareness was analyzed across four major areas, i.e., transmissions, clinical symptoms, prevention, and treatment.

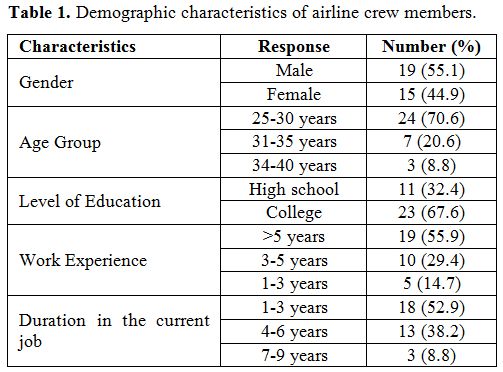

The demographic profile of respondents is summarized in Table 1. Out of forty participants, only 34 (85%) responded to the questionnaires and included in the further analysis. The majority of the participants (n=19, 55% and n=24, 70.6%) were male and in the age group of 25-30 years, respectively. According to the level of education and work experience, more than two-thirds (n=23, 67.6%) had a college education, 55.9% (n=19) had more than five years of work experience, and 52.9% (n=18) were in the current job for the past 1-3 years.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of airline crew members. |

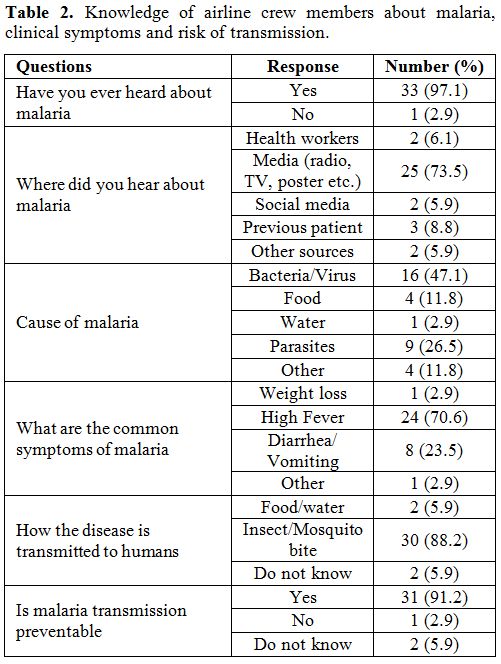

Table 2 shows the general knowledge of malaria, symptoms, and transmission among airline crewmembers. The majority of the respondents (n=26, 76.5%) knew about the malaria high-risk countries.

|

Table 2. Knowledge of airline crew members about malaria, clinical symptoms and risk of transmission. |

The most of respondents (88,2%) was aware of the danger of transmission of this disease through the mosquito bite, even if the majority (n=25, 73.5%) of them have a superficial acknowledge acquired through both current audiovisual or print media. Only 8.8% (n=3) has a direct experience through previous patients and 5.9% (n=2) through social media. The vast majority of the respondents (n=24, 70.6%) indicated high fever as the most common symptom of malaria, whereas the 23.5% (n=8) and 2.9% (n=1) believed that diarrhea/vomiting and weight loss were respectively the main symptoms. Surprisingly, 47.1% (n=16) respondents stated that malaria is caused by a virus and/or bacteria, and only 26.5% (n=9) by parasites.

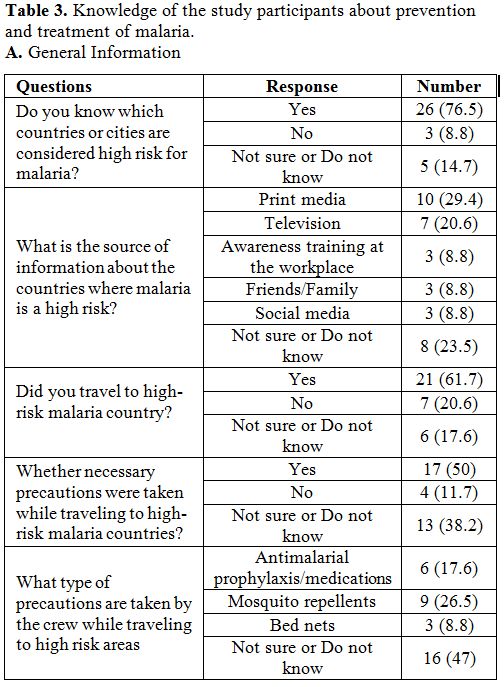

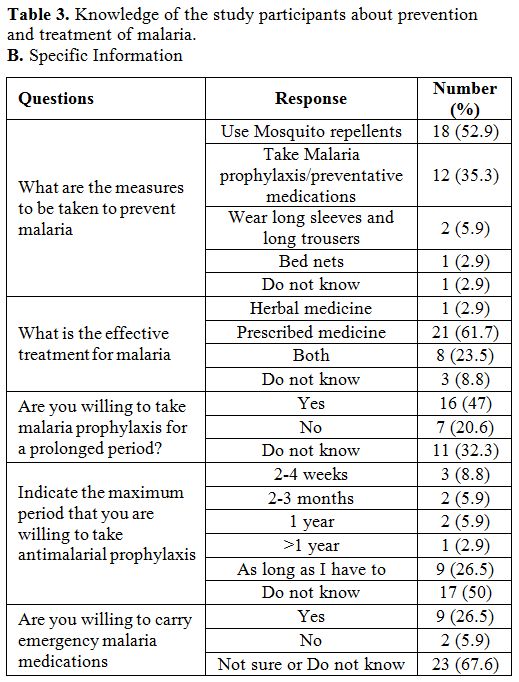

Furthermore, the knowledge of crewmembers regarding the prevention and treatment of malaria is shown in Table 3 A and B. The majority of the respondents (n=18, 52.9%) were knowledgeable about the use of mosquito repellents, but only 35.3% (n=12) revealed that taking prophylaxis or preventive medications could prevent malaria. Besides, most respondents (n=21, 61.7%) knew malaria treatment and prescribed medication. The 26.5% (n=9) were keen to carry antimalarial emergency medication.

|

Table 3A. Knowledge of the study participants about prevention and treatment of malaria. General Information. |

|

Table 3B. Knowledge of the study participants about prevention and treatment of malaria. Specific Information. |

Furthermore, and 29.4% (n=10) gathered information from newspapers or magazines followed by television, social media, and friends/family. The majority of respondents (n=21, 61.7%) had travel history to malaria high-risk countries, most of them (n=17, 50%) took necessary precautions prior traveling to the malarious area, and 26.5% (n=9) used mosquito repellents followed by antimalarial prophylaxis and bed nets.

The risk assessment evaluated the risk activities that crew engaged in between dusk and dawn and the corresponding use of measures to prevent mosquito exposure.

In the present study, the analysis of malaria prevention knowledge revealed that most of the respondents had used mosquito repellents, followed by anti-malarial drugs as the main precaution against malaria. Besides, the findings in the present study shown that the cabin crewmembers were adequately aware of the mode of malaria transmission, and the importance of the mosquitos’ bites, however, it revealed also that most of the cabin crew not have a good level of knowledge about malaria, its causes, symptoms, transmission, prevention, and treatment.

Making a comparison with the previous studies appears evident the all the staffs are aware of the risk of infection by the transmission of the mosquitos. However, the measures of prevention are not always the same, and it is difficult to understand when and if applied. Furthermore, the use of drug prophylaxis was ignored or undervalued. However, according to the data of Byrn et Al., the risk of crew acquiring malaria is too low to recommend universal antimalarial prophylaxis and should be reserved for particular situations. Major importance to the drugs prophylaxis is given by the crew interviewed by Selent et Al. A major concern is not giving the right importance to have available adequate drugs for emergy treatment.[10,12]

In conclusion, the majority of the study participants have heard about malaria by media, and only a small percentage obtained the information via proper orientation or training. Based on this, there is a need to introduce further programs to improve the awareness of cabin crew about malaria and the importance of taking necessary precaution for malaria. Subsequently, this would assist in improving cabin crew knowledge of prevention, effective treatment, and necessary precautions on malaria, so decreasing their risk of contracting malaria. To protect airline cabin crewmembers flying to malaria-endemic destinations, effective and safe prophylactic medication should be provided in addition to the education of individual measures to prevent mosquito bites.[11] The better education of airline crew could reduce the barriers to malaria prevention found by most traveling people.[12] The limitation of the present study is small sample size; hence, results cannot be generalized but provide baseline information on the crew awareness and knowledge about malaria. There is a need for further study with a larger sample size to confirm the present findings and to assess additional training or awareness campaigns for the crew about malaria. Further, it would be important for future researchers to allocate more time and to focus on more malaria awareness aspects, such as recommended prevention measures by health professionals.