Hye Jo Shin1, Eui Soo Lee1, Seung Beom Han1,2, Jae Wook Lee1,3, Nack-Gyun Chung1,3, Bin Cho1,3 and Jin Han Kang1,2..

1 Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

2 The Vaccine Bio Research Institute, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

3 Catholic Hematology Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

Correspondence to: Jin Han Kang, MD, PhD, Professor. Department of

Pediatrics, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The

Catholic University of Korea, 222 Banpo-daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul 06591,

Republic of Korea. Tel.: 82 2 2258 6183; Fax.: 82 2 537 4544. E-mail:

kjhan@catholic.ac.kr

Published: September 1, 2019

Received: May 22, 2019

Accepted: August 9, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11(1): e2019052 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2019.052

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background: Vaccination

for hepatitis B virus (HBV) after chemotherapy among pediatric patients

with acute Leukemia is still a debated issue. We investigated HBV

immunity before and after chemotherapy and assessed immune response to

re-vaccination after chemotherapy.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed data of children and adolescents aged

<19 years requested for vaccination after chemotherapy for acute

leukemia to evaluate hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) status before

and after chemotherapy and to identify factors related to HBsAb

positivity after chemotherapy.

Results:

Of 89 enrolled patients, 61 (68.5%) with acute leukemia were HBsAb

positive before chemotherapy.Of these 61 patients, 48 (78.7%)

seroconverted to HBsAb negative status after chemotherapy; there were

76 (85.4%) HBsAb negative patients after chemotherapy. HBsAb positive

patients when compared to HBsAb negative patients after chemotherapy

had a significantly higher HBsAb positive rate (100.0% vs. 63.2%, p=0.008)

before chemotherapy. Following HBsAb testing after one dose of the HBV

vaccination, 33 (43.4%) of the 76 HBsAb negative patients seroconverted

to an HBsAb positive status. HBsAb positive patients after a single

dose of HBV vaccination had a significantly higher HBsAb positive rate

at the time of diagnosis compared to HBsAb negative patients (84.8% vs.

48.8%, p=0.001).

Conclusions:

Based on these results, HBV re-vaccination after chemotherapy is

recommended for all children and adolescents with acute leukemia. In

addition, further investigation is required to improve the

immunogenicity of HBV re-vaccination.

|

Introduction

Given

higher survival rates in patients with acute leukemia due to

advancements in chemotherapy technologies and conservative treatment

for cancer patients,[1] it has become more important to prevent

long-term complications after treatment. In particular, pediatric

cancer patients have a longer survival period after treatment than

adult patients, and they are more likely to be affected by

vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) during this period. Therefore, it

is necessary to establish a vaccination policy for pediatric cancer

patient survivors. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a well-known

VPD. The worldwide prevalence of HBV infection significantly decreased

after HBV vaccination during infancy was introduced.[2]

Even in

low HBV infection endemic areas, there is a need to focus on prevention

of HBV infection after anti-cancer treatment as well as prevention and

treatment of reactivation of a previous HBV infection caused by

immune-compromised conditions or de novo HBV infection during

chemotherapy for acute leukemia.[3] The 2013 Guideline for Vaccination

of the Immunocompromised Host by the Infectious Diseases Society of

America states that all patients, who received hematopoietic cell

transplantations (HCTs), are recommended to have HBV vaccination after

transplantation.[3] However, not all patients who underwent

chemotherapy for acute leukemia are advised to undergo HBV vaccination

after chemotherapy, except in certain cases based on age and risk

factors.[3] One previous study reported that the positive rate of

hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) remained high after chemotherapy

for pediatric acute leukemia; thus, it was recommended that such

patients should continue the standard vaccination schedule.[4] In

contrast, other studies have reported that universal HBV vaccination

was required due to a significantly reduced HBsAb positive rate after

chemotherapy for acute leukemia.[5-7] Additionally, a recent

vaccination guideline for patients with hematological malignancies of

the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL7)

supports this universal vaccination strategy.[8]

The subjects in

the present study were pediatric patients with acute leukemia from

Korea, a low intermediate HBV infection endemic area where almost all

children and adolescents have acquired immunity from vaccination during

infancy. To facilitate the development of an HBV vaccination policy

after chemotherapy for children and adolescents treated with

chemotherapy only, we evaluated the HBsAb positive rate before and

after treatment for acute leukemia. We also evaluated the

immunogenicity of HBV vaccine after chemotherapy.

Patients and Methods

Subjects.

Patients included in this study were aged <19 years at the time of

leukemia diagnosis, received chemotherapy for acute leukemia in the

Department of Pediatrics at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic

University of Korea, and were referred to the division of Pediatric

Infection Diseases between January 2015 and June 2018 for vaccination

after chemotherapy. Of the 187 referred patients, 64 who had received

HCTs were excluded. From the remaining 123 patients, treated with

chemotherapy only, we excluded 33 who did not have an HBsAb test at the

time of diagnosis with acute leukemia, and one who received a

qualitative radioimmunoassay (RIA) test for HBsAb instead of a

quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Retrospective

analysis of the medical records for the remaining 89 patients was

performed. The present study was performed after obtaining approval

from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital

(Approval number: KC18RESI0503).

Data collection and definitions.

Demographic data, including sex and age, were gathered at the diagnosis

of leukemia. Clinical data, including type of underlying acute leukemia

and its treatment results, the risk group of acute lymphoblastic

leukemia (ALL), time intervals between completion of chemotherapy and

HBsAb testing, and between completion of chemotherapy and HBV

vaccination, HBsAb titers at the time of acute leukemia diagnosis and

after completing chemotherapy, and the complete blood cell count at the

time of the HBsAb testing, were investigated. Furthermore, HBsAb titers

after HBV vaccination were also investigated in patients who received

HBV vaccination after chemotherapy. HBsAb tests were performed using a

commercial quantitative ELISA kit (Elecsys® Anti-HBs, Roche Diagnostics

GmBH, Mannheim, Germany); titers were summarized as follows: titers

<2 IU/L, corresponding to the threshold of the test, were

categorized as 1 IU/L and those >1,000 IU/L were categorized as

1,000 IU/L. Positive and negative antibodies were defined as HBsAb

levels of ≥10 IU/L and <10 IU/L, respectively. Patients testing

negative for HBsAb after chemotherapy received one dose of HBV vaccine

(Hepavax-Gene® TF, Janssen Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea) at a dose of 0.5

mL (10 μg of hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg]) for patients aged

<11 years, and 1.0 mL (20 μg of HBsAg) for those aged ≥11 years.

After at least 4 weeks post-vaccination, the HBsAb test was again

performed. HBsAb negative patients whose HBsAb level increased to ≥10

IU/L after HBV vaccination were considered to have an anamnestic

response. For patients still negative for HBsAb after one dose of HBV

vaccine, a second and third dose were administered at least 1 month and

6 months after the first HBV vaccination, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

The subjects were divided into HBsAb negative and positive patients

based on their HBsAb titer after chemotherapy. Demographic and clinical

data were compared between these two patient groups. Based on the HBsAb

retest results determined after one dose of HBV vaccine in patients who

received an HBV vaccination after chemotherapy, patients were divided

into those with and without an anamnestic response, and then the two

groups were compared. For comparison of continuous data and categorical

data between the patient groups, Mann-Whitney U and Fisher’s exact

tests were applied, respectively. The SPSS 21 program (IBM Corporation,

Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses, and statistical

significance was defined as a p-value <0.05.

Results

The

89 study subjects included 58 (65.2%) males and 31 (34.8%) females with

a median age of 8 years (range, 1-18 years). At baseline, there were 79

(88.8%) patients with ALL and 10 (11.2%) with acute myeloid leukemia

(AML); all were at their first complete remission state. At the time of

their diagnosis with acute leukemia, 61 (68.5%) patients were HBsAb

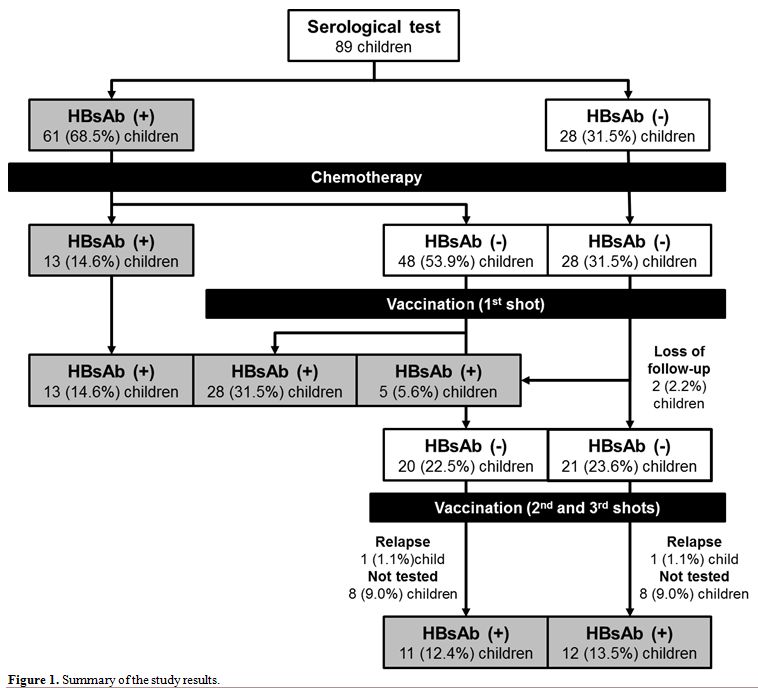

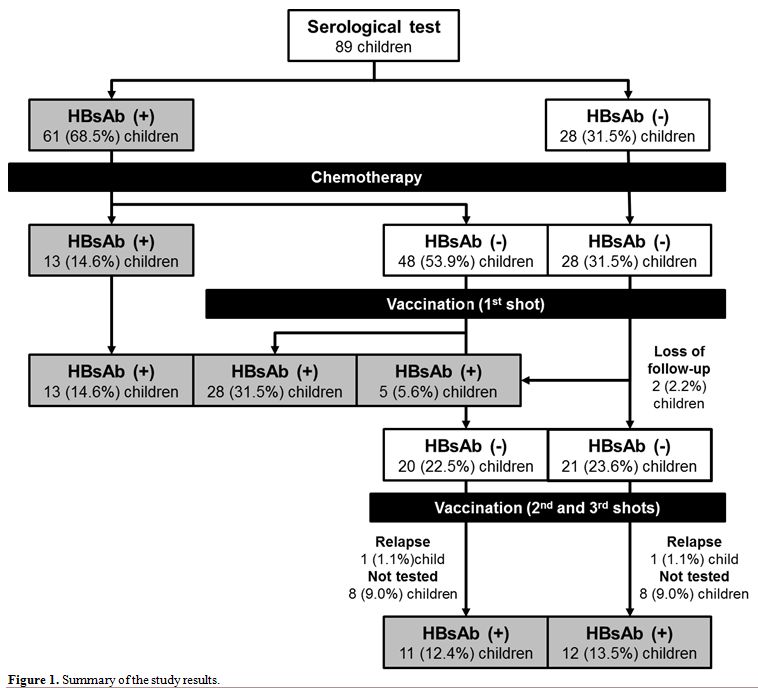

positive (Figure 1); their

median HBsAb titer was 67.15 IU/L (range, 11.02-1,000.00 IU/L). HBsAb

positivity at the time of leukemia diagnosis was not associated with

sex or type of underlying leukemia. However, significantly more

patients aged <7 years were HBsAb positive compared to those and ≥7

years old (86.4% vs 62.7%, p=0.038) at the time of diagnosis.

|

Figure 1. Summary of the study results. |

Comparison between HBsAb positive and negative patients after chemotherapy.

HBsAb testing was performed at a median of 3 months (range, 0-14

months) after completing chemotherapy. Two (2.2%) patients had received

1 g/kg of intravenous immunoglobulin 7 months before an HBsAb test.

Regarding the 61 patients who were HBsAb positive at the time of

leukemia diagnosis, 48 (78.7%) seroconverted to HBsAb negative after

chemotherapy (Figure 1). For

the remaining 13 (21.3%) patients who remained HBsAb positive after

chemotherapy, the median HBsAb titer of 40.91 IU/L (range, 11.48-256.70

IU/L) was significantly lower than the 169.20 IU/L (range, 16.30-1,000

IU/L) reported at the time of their leukemia diagnosis (p=0.003). This

median titer for these 13 patients at the time of leukemia diagnosis

was significantly higher than the HBsAb titer determined at the time of

leukemia diagnosis for the other 48 patients who seroconverted to

negative after chemotherapy; the median was 53.57 IU/L (range,

11.02-819.00 IU/L, p=0.021). Only 30.6% (11/36) and 32.0% (8/25) of

patients with an HBsAb titer of ≥50.00 IU/L and ≥100.00 IU/L before

chemotherapy, respectively, remained HBsAb positive after chemotherapy.

Compared to patients who were HBsAb negative after chemotherapy, more

HBsAb positive patients had AML as an underlying disease (p<0.001)

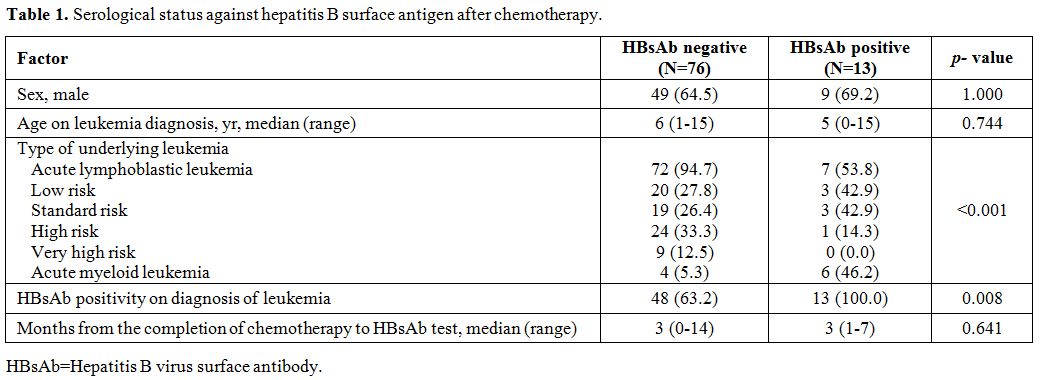

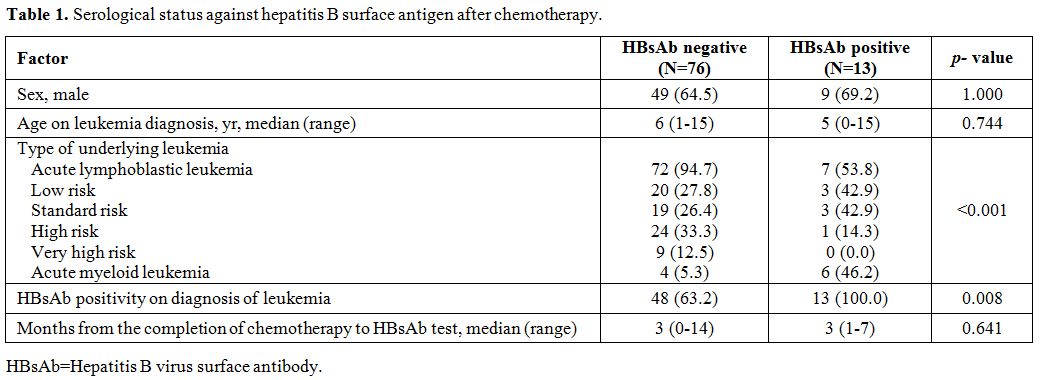

and were HBsAb positive at the time of leukemia diagnosis (p=0.008, Table 1).

The risk group of ALL was not significantly associated with HBsAb

positivity after chemotherapy. Younger age significantly correlated

with HBsAb positivity at the time of diagnosis, but this correlation

was not observed following chemotherapy. White blood cell, neutrophil

and lymphocyte counts determined on the day of HBsAb testing were not

significantly different between the two patient groups (data not shown).

|

Table 1. Serological status against hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy. |

Anamnestic response to the additional HBV vaccination after chemotherapy.

All 76 patients who were HBsAb negative after chemotherapy received one

dose of HBV vaccine at a median of 7 months (range, 3-18 months) after

completing chemotherapy; of these, 74 were subjected to an antibody

test at least 4 weeks after vaccination. Of these 74 patients, 33

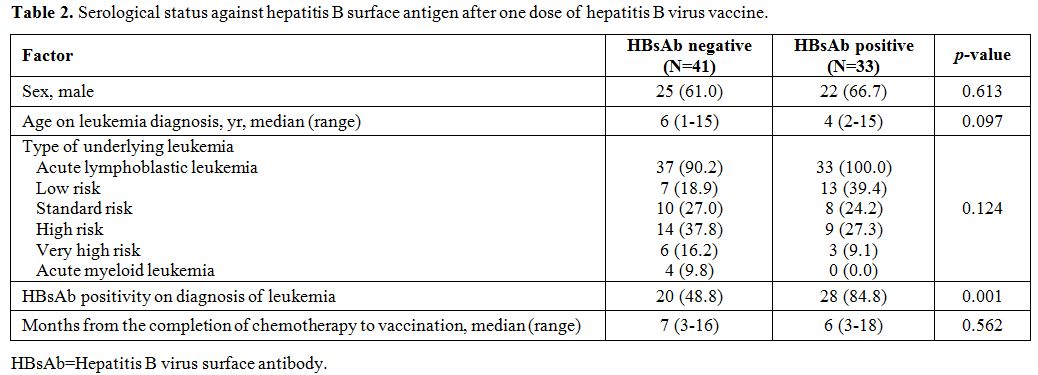

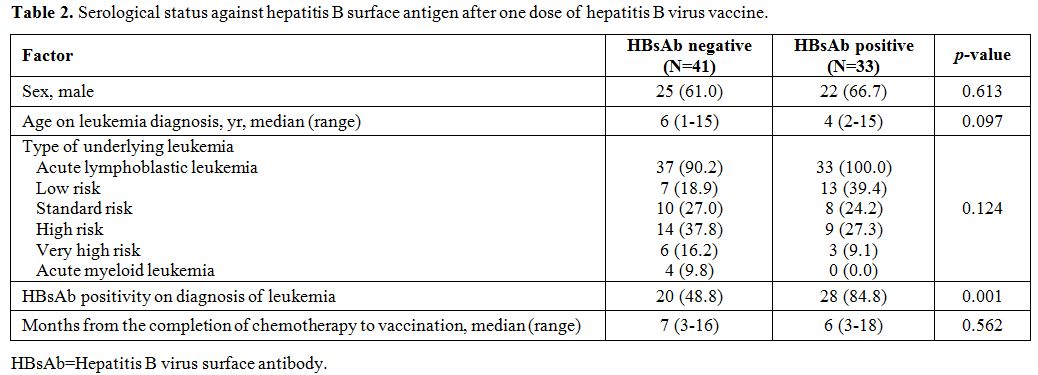

(44.6%) seroconverted to HBsAb positive (Figure 1, Table 2),

with a median titer of 45.72 IU/L (range, 10.27-1,000 IU/L). In

comparison to the 41 patients who remained HBsAb negative after

vaccination, the 33 seropositive patients were significantly more

likely to be HBsAb positive (p=0.001, Table 2)

and to have a higher HBsAb titer (median 8.22 IU/L vs 54.05 IU/L,

p<0.001) at the time of leukemia diagnosis. White blood cell,

neutrophil and lymphocyte counts determined on the day of first HBsAb

test after chemotherapy were not significantly associated with

anamnestic response to HBV vaccination after chemotherapy (data not

shown). Of the 41 HBsAb negative patients, after one dose of HBV

vaccination, 40 (excluding one patient with ALL relapse) received a

second HBV vaccination, and 36 received a third vaccination (excluding

one patient with ALL relapse after the second vaccination, one patient

who was lost to follow-up after the second vaccination, and two who

dropped out for unknown reasons). Regarding the 36 patients who

received the third vaccination, 23 who had an antibody test performed

after vaccination seroconverted to HBsAb positive, with a median HBsAb

titer of 1,000 IU/L (range, 40.69-1,000 IU/L).

|

Table 2. Serological status against hepatitis B surface antigen after one dose of hepatitis B virus vaccine. |

Discussion

This

study investigated HBV immunity before and after chemotherapy for acute

leukemia and immune response to re-vaccination after chemotherapy. We

found that 68.5% of children and adolescents who were diagnosed with

acute leukemia were HBsAb positive at leukemia diagnosis. Of these

HBsAb positive patients, 78.7% seroconverted to HBsAb negative after

chemotherapy. As a result, 85.4% of all patients were HBsAb negative

after chemotherapy. Of these patients, 44.6% seroconverted to HBsAb

positive after a single HBV vaccination. Hence, 51.7% of all patients

were HBsAb positive after one dose (Figure 1). All patients, who were subjected to testing after a third dose, exhibited seroconversion to an HBsAb positive status.

Although

the HBV vaccination history could not be determined for all patients in

the present study, 80.9% of the enrolled patients have received their

three doses of vaccination during infancy; a rate that was determined

based on their vaccination records. Furthermore, since mandatory HBV

vaccination (thrice at birth and then at 1 and 6 months after birth)

was incorporated into the National Immunization Program of Korea in

1995 with a maintenance of an HBV vaccination rate >93% after the

2000s,[9] almost all study subjects should have acquired HBsAb from HBV

vaccination during infancy. Although the majority (95%) of healthy

infants were HBsAb positive after three doses of primary HBV

vaccination,[2] antibody titer and seroprevalence decreased over time,

resulting in a 50-60% HBsAb positivity rate among children aged 6-8

years.[10-12] The HBsAb positive rate of the children enrolled in the

present study (with a median age of 6 years) was similar to that of

healthy children at 68.5%. HBsAb seroprevalence in healthy Korean

children has been found to decrease by 17.0% from the age of six to

eight,[10] whereas, the rate of seroconversion to HBsAb negative status

of the patients enrolled in the present study was 78.7% during

approximately 3 years of chemotherapy. This seroconversion rate was

higher than the previously reported rates of 27.4-53.8% in pediatric

patients receiving chemotherapy for hematological

malignancies.[7,13,14] We speculate that the seroconversion rate could

have been affected by differences in either intensity of chemotherapy

among patients, antibody test methods, or the sensitivity and

specificity of the ELISA kit used. Overall HBsAb positive rate after

chemotherapy for hematological malignancy including acute leukemia

ranges from 14.0-80.6% in studies, including this one.[4-7,13-16]

However, all studies, except the one that showed the 80.6% positive

rate, were below a 50% positive rate. Therefore, there is a need for

universal HBV vaccination policy for patients with acute leukemia after

chemotherapy rather than vaccination based on HBsAb test results,

reconfirming the recent ECIL7 guideline for vaccination in patients

with hematological malignancies.[8] HBsAb positivity in patients with

acute leukemia after chemotherapy exhibited no significant correlation

with age, sex, underlying leukemia, or the intensity of

chemotherapy.[5-7,14,16] In the present study, patients who were HBsAb

positive after chemotherapy had a significantly higher HBsAb positive

rate and a significantly higher HBsAb titer before chemotherapy

compared to those who were HBsAb negative after chemotherapy. Although

a similar result was reported in another study,[14] the other study

reported no significant correlation in HBsAb positivity before and

after chemotherapy.[16] In healthy children, those with a higher HBsAb

titer after their primary HBV vaccination during infancy exhibited a

higher anamnestic response rate to re-vaccination after several

years.[17-19] As such a higher HBsAb titer before chemotherapy may be

considered to be a contributing factor to HBsAb positivity after

chemotherapy. However, with low rates of patients with either HBsAb ≥10

IU/L (21.5%) or ≥100 IU/L (33.3%) before chemotherapy remaining HBsAb

positive after chemotherapy, the prediction of HBsAb positivity after

chemotherapy based on HBsAb positivity before chemotherapy would have

limited usefulness in real-world clinical settings.

In the present

study, about half of the patients had an anamnestic response after

their initial HBV vaccination after chemotherapy. This implied that the

remaining 48.3% of patients were HBsAb negative despite a single HBV

vaccination after chemotherapy. In previous studies, higher percentages

(63.2-95.7%) of patients who were HBsAb negative after chemotherapy

were found with an anamnestic response after HBV vaccination.[5,7,15]

Almost all (92.9-100%) healthy adolescents who receive their three

doses of primary HBV vaccine during infancy have an anamnestic response

to HBV re-vaccination, even after 10-20 years.[20-22] However, as low

as 47.9% of healthy adolescents show an anamnestic response to

re-vaccination after 15 years of HBV vaccination in infancy.[23] Such

low anamnestic responses occurred when all three doses of the primary

vaccination were administered within 6 months of birth, or when a

low-dose vaccine (2.5 or 5.0 μg of HBsAg) was used.12 In Korea, a 10 μg

HBsAg vaccine has been used for infants; however, the vaccination is

performed thrice within their first 6 months of age. It is, in fact,

impossible to alter the national primary vaccination schedule for

patients with acute leukemia only; thus, it is necessary to identify

adjustable factors after chemotherapy that can improve HBV vaccine

immunogenicity. Accordingly, it makes sense to consider the appropriate

time interval between completion of chemotherapy and HBV vaccination.

Although restoration of B-cells can be achieved 3-6 months following

completion of chemotherapy, it may take several years for the

restoration of memory B-cell counts.[24] In the present study, HBsAb

testing and HBV vaccination were performed at medians of 3 and 7 months

after completion of chemotherapy, respectively. Considering that

previous studies described a >90% HBsAb seroconversion rate with HBV

vaccination at least 15 months after chemotherapy,[5,7] an improved

anamnestic response through delayed vaccination after the full

restoration of memory cells should be possible. Therefore, vaccination

may need to be postponed in countries with a low prevalence of HBV

infection until there is a full restoration of lymphocytes in number

and functionality, and one dose of vaccine rather than three doses may

be adequate after chemotherapy with this strategy. Follow-up studies

are needed to determine the appropriate time of immunity restoration

after chemotherapy, in order to allow for the acquisition of full

vaccine immunity without morbidity from VPDs. In addition, the

immunogenicity of HBV vaccines after chemotherapy may be enhanced by

the use of new adjuvant vaccines, vaccines containing new antigens, or

vaccines with increasing dose of antigens.[25]

The present study

has some limitations. Since there was no screening for antibodies

against the HBV core antigen, it was not possible to establish which

patients were previously HBV-infected. Patient history of HBV

vaccination before chemotherapy was also not determined for all of the

enrolled patients. However, with the recent high HBV vaccination rate

during infancy and decreasing HBV infection prevalence in Korea, most

patients should receive HBV vaccination before chemotherapy; thus, only

few children should be HBV-infected. The present study also excluded

patients not screened for HBV serology at the time of diagnosis, or who

had RIA test instead of ELISA. Therefore, unified test items, times,

and methods are necessary from the time of diagnosis with acute

leukemia for future studies to establish an accurate vaccination

schedule after chemotherapy.

Conclusions

The

present study was unable to identify the significant factors of HBsAb

positivity after chemotherapy and seroconversion by HBV vaccination

after chemotherapy. However, it is useful to know that all patients

should receive HBV vaccination after chemotherapy for acute leukemia in

regions where almost all children have acquired HBV immunity from

vaccination during infancy, and there is a low prevalence of HBV

infection, in accordance with the recent ECIL7 guideline. In addition,

there should be on-going studies on the appropriate vaccination time

after chemotherapy and improving the immunogenicity of vaccines in

immunocompromised patients.

References

- Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1541-1552. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1400972 PMid:26465987

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper - July 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92:369-392.

- Rubin

LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, Bousvaros A,

Dhanireddy S, Sung L, Keyserling H, Kang I; Infectious Diseases Society

of America. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of

the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e44-100. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit684 PMid:24311479

- Fioredda

F, Plebani A, Hanau G, Haupt R, Giacchino M, Barisone E, Balbo L,

Castagnola E. Re-immunisation schedule in leukaemic children after

intensive chemotherapy: a possible strategy. Eur J Haematol.

2005;74:20-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00340.x PMid:15613102

- Fayea

NY, Kandil SM, Boujettif K, Fouda AE. Assessment of hepatitis B virus

antibody titers in childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Pediatr.

2017;176:1269-1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2970-4 PMid:28730317

- Viana

SS, Araujo GS, Faro GB, da Cruz-Silva LL, Araujo-Melo CA, Cipolotti R.

Antibody responses to Hepatitis B and measles-mumps-rubella vaccines in

children who received chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2012;34:275-279. https://doi.org/10.5581/1516-8484.20120071 PMid:23049440 PMCid:PMC3460395

- Zignol

M, Peracchi M, Tridello G, Pillon M, Fregonese F, D'Elia R, Zanesco L,

Cesaro S. Assessment of humoral immunity to poliomyelitis, tetanus,

hepatitis B, measles, rubella, and mumps in children after

chemotherapy. Cancer. 2004;101:635-641. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20384 PMid:15274078

- Mikulska

M, Cesaro S, de Lavallade H, Di Blasi R, Einarsdottir S, Gallo G,

Rieger C, Engelhard D, Lehrnbecher T, Ljungman P, Cordonnier C;

European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia group. Vaccination of

patients with haematological malignancies who did not have

transplantations: guidelines from the 2017 European Conference on

Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e188-199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30601-7

- Choung

JM, Kim JC, Eun SH, Hwang PH, Nyhambat B, Kilgore P, Kim JS. Study on

vaccination state in children : Jeonbuk province, 2000. Korean J

Pediatr. 2002;45:1234-1240.

- Kim

YJ, Li P, Hong JM, Ryu KH, Nam E, Chang MS. A Single Center Analysis of

the Positivity of Hepatitis B Antibody after Neonatal Vaccination

Program in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:810-816. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.810 PMid:28378555 PMCid:PMC5383614

- Qawasmi

M, Samuh M, Glebe D, Gerlich WH, Azzeh M. Age-dependent decrease of

anti-HBs titers and effect of booster doses using 2 different vaccines

in Palestinian children vaccinated in early childhood. Hum Vaccin

Immunother. 2015;11:1717-1724. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1041687 PMid:25996579 PMCid:PMC4514285

- Schonberger

K, Riedel C, Ruckinger S, Mansmann U, Jilg W, Kries RV. Determinants of

long-term protection after hepatitis B vaccination in infancy: a

meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:307-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31827bd1b0 PMid:23249904

- Alavi

S, Rashidi A, Arzanian MT, Shamsian B, Nourbakhsh K. Humoral immunity

against hepatitis B, tetanus, and diphtheria following chemotherapy for

hematologic malignancies: a report and review of literature. Pediatr

Hematol Oncol. 2010;27:188-194. https://doi.org/10.3109/08880011003602141 PMid:20367262

- Keskin

Yildirim Z, Buyukavci M. Assessment of humoral immunity to hepatitis B,

measles, rubella, and mumps in children after chemotherapy. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol. 2018;40:e99-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000001072 PMid:29309372

- Baytan

B, Gunes AM, Gunay U. Efficacy of primary hepatitis B immunization in

children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian Pediatr.

2008;45:265-270.

- Karaman

S, Vural S, Yildirmak Y, Urganci N, Usta M. Assessment of hepatitis B

immunization status after antineoplastic therapy in children with

cancer. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:573-576. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.87091 PMid:22048500 PMCid:PMC3221126

- Chaves

SS, Fischer G, Groeger J, Patel PR, Thompson ND, Teshale EH, Stevenson

K, Yano VM, Armstrong GL, Samandari T, Kamili S, Drobeniuc J, Hu DJ.

Persistence of long-term immunity to hepatitis B among adolescents

immunized at birth. Vaccine. 2012;30:1644-1649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.106 PMid:22245310

- Wu

JS, Hwang LY, Goodman KJ, Beasley RP. Hepatitis B vaccination in

high-risk infants: 10-year follow-up. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1319-1325.

https://doi.org/10.1086/314768 PMid:10228050

- Dentinger

CM, McMahon BJ, Butler JC, Dunaway CE, Zanis CL, Bulkow LR, Bruden DL,

Nainan OV, Khristova ML, Hennessy TW, Parkinson AJ. Persistence of

antibody to hepatitis B and protection from disease among Alaska

natives immunized at birth. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:786-792. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000176617.63457.9f PMid:16148845

- Bagheri-Jamebozorgi

M, Keshavarz J, Nemati M, Mohammadi-Hossainabad S, Rezayati MT,

Nejad-Ghaderi M, Jamalizadeh A, Shokri F, Jafarzadeh A. The persistence

of anti-HBs antibody and anamnestic response 20 years after primary

vaccination with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine at infancy. Hum Vaccin

Immunother. 2014;10:3731-3736. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.34393 PMid:25483689 PMCid:PMC4514033

- Van

Der Meeren O, Behre U, Crasta P. Immunity to hepatitis B persists in

adolescents 15-16 years of age vaccinated in infancy with three doses

of hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine. 2016;34:2745-2749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.013 PMid:27095043

- Zanetti

AR, Mariano A, Romano L, D'Amelio R, Chironna M, Coppola RC, Cuccia M,

Mangione R, Marrone F, Negrone FS, Parlato A, Zamparo E, Zotti C,

Stroffolini T, Mele A; Study Group. Long-term immunogenicity of

hepatitis B vaccination and policy for booster: an Italian multicentre

study. Lancet. 2005;366:1379-1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67568-X

- Bialek

SR, Bower WA, Novak R, Helgenberger L, Auerbach SB, Williams IT, Bell

BP. Persistence of protection against hepatitis B virus infection among

adolescents vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning

at birth: a 15-year follow-up study. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

2008;27:881-885. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31817702ba PMid:18756185

- van

Tilburg CM, van Gent R, Bierings MB, Otto SA, Sanders EA, Nibbelke EE,

Gaiser JF, Janssens-Korpela PL, Wolfs TF, Bloem AC, Borghans JA,

Tesselaar K. Immune reconstitution in children following chemotherapy

for haematological malignancies: a long-term follow-up. Br J Haematol.

2011;152:201-210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08478.x PMid:21114483

- Saco

TV, Strauss AT, Ledford DK. Hepatitis B vaccine nonresponders: Possible

mechanisms and solutions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:320-327.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.017 PMid:29567355