Salam Alkindi1,2#, Nada AL-Umairi1, Sanjay Jaju2 and Anil Pathare1.

1 Department of Haematology, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman.

2 College of Medicine & Health Sciences, Muscat, Oman.

Correspondence to: Dr. Salam Alkindi, BA, MB, BCh, BAO, MSc, FRCP.

Professor in Haematology and Consultant Haematologist, Department of

Haematology, College of Medicine & Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos

University, P. O. Box 35, Muscat 123, Sultanate of Oman. Tel.:

+96824141182, Fax: +96824144887. E-mail:

sskindi@yahoo.com

Published: November 1, 2019

Received: July 29, 2019

Accepted: September 24, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11(1): e2019058 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2019.058

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

In Oman, the prevalence of hepatitis B (HBV) infection is 5.8%, with

2.8–7.1% HBV carriers. Hepatitis C (HCV) prevalence among Omanis is

0.41%. A total of 2917 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections

were notified among Omanis by 2017. This study was performed as there

was no data on the prevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV in sickle cell

disease (SCD) patients from Oman.

Study Design and Methods:

In this retrospective, cross-sectional study, medical records of all

SCD patients who attended our hospital between 2011 to 2017 were

retrieved from the hospital information system. Following approval by

the local medical research and ethics committee, data on HIV, HBV, and

HCV exposure were recorded to estimate the prevalence.

Results:

Among a total of 1000 SCD patients (491 males and 509 females),

twenty-three (2.3%) patients showed positive serology for hepatitis B

surface antigen (HbsAg), of whom sixteen (1.6%) were HBV DNA

positive. 126 (12.6%) had anti-HCV antibodies (anti-HCV), of whom

fifty-two (5.2%) were HCV RNA positive. None of the patients had

positive serology for HIV. A normal liver was observed on abdominal

ultrasound in 788 (78.8%) patients, whereas 208 (20.8%) had

hepatomegaly, and 4 (0.4%) had liver cirrhosis. Thirty-six (3.6%)

patients died, but in only two patients, the mortality was due to

cirrhosis of liver.

Conclusions:

This study provides the first comprehensive data on the prevalence of

HBV and HCV infections among Omani SCD patients exposed to blood

transfusions. Reassuringly, no case with HIV was observed.

|

Introduction

Sickle-cell

disease (SCD) is a monogenic disorder characterized by a mutation in

the beta-globin gene, where glutamic acid is replaced by valine,

resulting in the polymerization of Hb and formation of Hb S, with many

devastating clinical manifestations.[1-2] It is not

only affecting red cells but also evolving into multi-system

involvement. Although the mutation of the sickle gene originated in the

African continent, it is now a world-wide disorder.[2,3] SCD is highly prevalent in Oman, with the reported incidence of sickle trait close to 6% of the population.[4-6]

The

most common complications of SCD are recurrent vaso-occlusive crises,

predisposition to significant anemia, acute chest syndrome and

recurrent infections.[7,8] Blood transfusion therapy

is one of the established therapies commonly used in the management of

SCD-related complications, including stroke, ACS, priapism,

pregnancy-related complications, and symptomatic anemia.[9]

Unfortunately, such transfusions increase the risk of exposure to

bloodborne infections like hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus

(HCV) and immune deficiency virus (HIV).

Chronic viral hepatitis

is a major global public health problem because of its association with

increased morbidity and mortality related to chronic hepatitis,

cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.[10] In 2015,

WHO Global hepatitis report describes the global and regional estimates

of viral hepatitis with an estimated 257 million people living with

chronic HBV infection and 71 million people with chronic HCV infection.[11]

The report also addresses mortality due to these infections, with viral

hepatitis causing 1.34 million deaths in 2015, a number comparable to

deaths caused by tuberculosis, but higher than those caused by HIV.

However, the number of deaths due to viral hepatitis is steadily

increasing over time, while mortality due to tuberculosis and HIV is

declining.[12]

SCD patients are at high risk

for transfusion-associated infections such as HBV, HCV, and HIV. The

prevalence of these infections in SCD has been studied worldwide. In

Mexico, the prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV in multi-transfused patients

was 7%, 13.7%, and 1.7%, respectively.[13] In Turkey

between 1996 to 2005, HBsAg positivity was found to be 0.79% whereas,

anti-HCV antibody positivity was 4.51%, but no HIV infections were

observed among multi-transfused patients.[14] In

comparison, Oman is a country with an intermediate prevalence of HBV

carriers (2.8–7.1%), reported by a retrospective study conducted in

2010, with a prevalence rate of 5.8% for HBV infection.[15] Further, among the entire resident population in Oman, anti-HCV antibody positivity was reported to be 0.41%.[16]

The WHO classifies Oman as having a low HIV prevalence, with total of

2917 HIV/AIDS infections among Omanis that were notified until end of

2017 with 1606 patients still being alive.[17]

Thus,

despite the high prevalence of SCD in Oman, there is no data on the

prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV in these patients. We, therefore,

conducted this retrospective study using electronic medical records to

estimate the prevalence of these infections and study its impact on

morbidity and mortality.

Material and Methods

This

is a retrospective cross-sectional study performed in patients with

SCD, admitted to our hospital between 2011 to 2017, and data is

obtained from the electronic patients' records (EPR). Among a total of

1012 EPR records that were retrieved, twelve patients were excluded

from the final analysis as their data was incomplete.

The

details obtained from the EPR records included: age, diagnosis,

frequency of blood transfusion, laboratory markers for hepatitis B

including surface antibody (anti-HBs), hepatitis B surface antigen

(HbsAg), anti-hepatitis B IgM (anti-HBc IgM), hepatitis B core total

antibodies (total anti-HBc), hepatitis B polymerase chain reaction (HBV

DNA), hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e-antibody (anti-HBe),

anti-hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), hepatitis C polymerase chain

reaction (HCV RNA), hepatitis C genotype (HCV Genotype), HIV.

Radiological data included abdominal liver ultrasound study results to

assess for hepatomegaly and cirrhosis of the liver. The frequency of

blood transfusions was categorized into four groups; never (no blood

transfusion), occasional (less than two times per year), intermittent

(3-6 times per year), and regular (monthly). Information was also

collected on the current status of patients to obtain mortality data.

All

blood samples were tested for HIV (anti-HIV 1/2), HBV HBsAg (if HBsAg

was positive, full markers were performed including HBeAg, and

anti-HBe, and total core IgM) and HCV. In case of HCV (anti-HCV)

serological markers were screened by Architect HCV Ag Test (Architect

HCV Ag Test, Abbot, Germany), and if positive were confirmed by second

confirmatory method, the electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on Cobas

e 411 immunoassay analyzer. Samples that were initially reactive by

ELISA were retested in duplicate, and results were interpreted

according to manufacturers’ instructions.

HCV antigen was tested

by third-generation assays (RIBA HCV 3, Chiron and HCV Blot, Genelab

Diagnostics, Singapore). Sera, reactive in ELISA, were tested by RIBA

according to manufacturers’ recommendations. In these assays specimens

were considered positive if they demonstrated reactivity to two or more

antigen bands at an intensity higher than or equal to the weak positive

control.

HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) was tested on samples using

the RT-PCR kit COBAS® AMPLICOR HCV Test, Version 2.0 (Roche Molecular

Systems Inc., Pleasanton, California, USA). Since 2009, HCV RNA

was tested using quantitative COBAS® TaqMan® analyzers (Roche Molecular

Systems Inc.) with a linear quantification range between <15 and 100

× 106 IU/mL and a lower limit of detection of 12.6 IU/mL.

HBV

infection was ascertained by assaying for HBeAg and HBsAg using

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Axsym, Abbott Laboratories). The

assay cut-off for HBeAg was ≥1 unit/ml and the assay cut-off for HBsAg

was ≥0.17–0.6 ng/ml; however, the assay cut-off varied according to the

lot number of the kit. HBV DNA level was assessed using plasma with the

platform of Roche COBAS® TaqMan® HBV Test, V1.0, with a linear

quantification range between <20 and 170 × 106 IU/mL.

HIV

(anti-HIV 1/2) was ascertained by an immunometric bridging technique

using the VITROS ECi/ECiQ Immunodiagnostic System. Any positive

serology would be confirmed by Western-Blot assay or HIV DNA PCR assay

using the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HIV-1 v2.0, with a linear

quantification range between <20 and 10 × 106 IU/mL.

Statistical Analysis.

The statistical package for social science (IBM SPSS, USA ver.23) was

used to analyze the collected data. Normally distributed data were

characterized as mean with standard deviation, whereas data for

continuous variable and percentage and frequency for categorical

variables. The prevalence was reported as counts and percentages as

appropriate.

Results

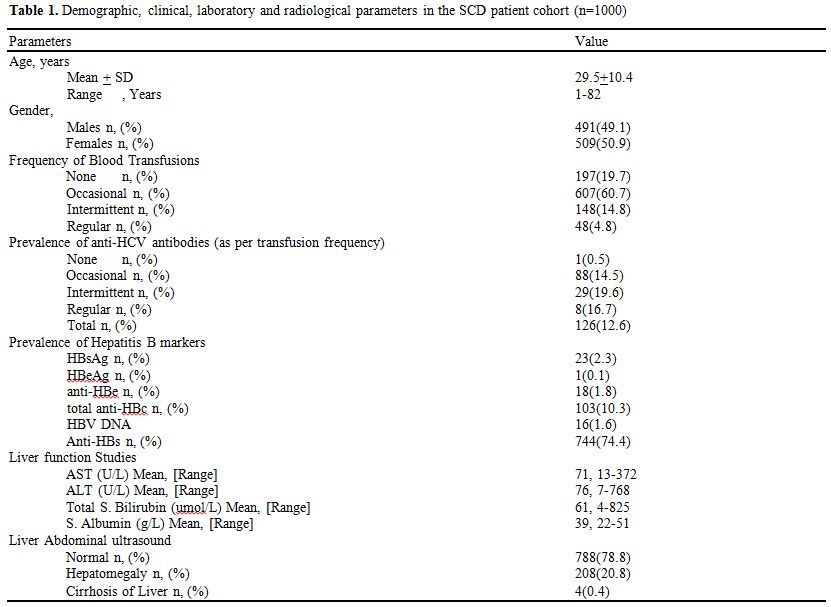

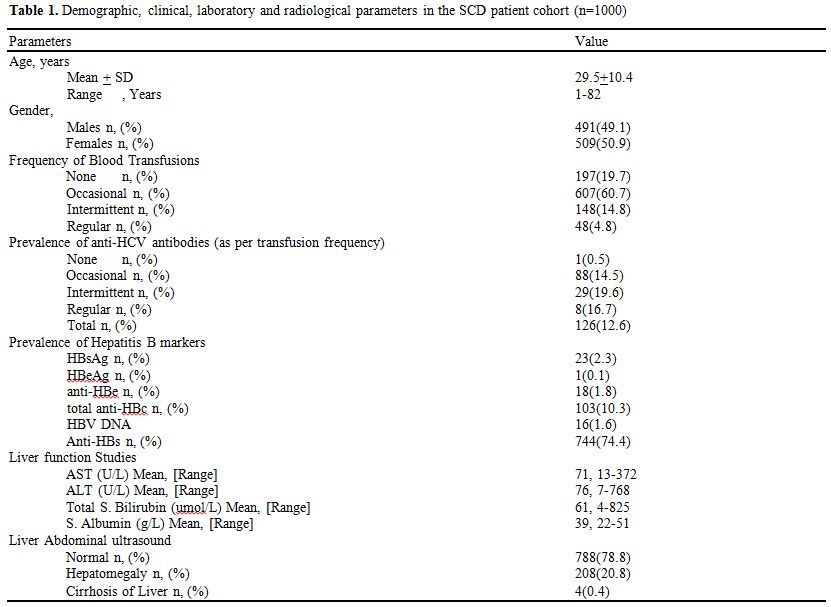

Table 1 shows

the data from 1000 SCD patients (491 males and 509 females) with a mean

age of 29.48 ± 10.40 years (range 1-82). 197 (19.7%) never received

blood transfusions, whereas, 607 (60.7%) had occasional transfusions,

148 (14.8%) had intermittent transfusions and 48 (4.8%) were receiving

regular transfusion.

|

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters in the SCD patient cohort (n=1000) |

In

this study cohort, twenty-three (2.3%) were positive by serology for

HBsAg, with sixteen (1.6%) being HBV DNA positive as well. Total

anti-HBc, anti-HBe, and HBeAg were positive in 10.3%,1.8%, and 0.1%,

respectively. 74.4% of these SCD patients showed anti-HBs positivity,

indicating adequate immunity against hepatitis B. 126 (12.6%) had

serologically positive anti-HCV antibodies (anti-HCV), with fifty-two

(5.2%) showing HCV RNA positivity. The prevalence of anti-HCV in SCD

patients with regular, intermittent, occasional and those with no

transfusion was 16.7%,19.6%,14.5% and 0.5% respectively. A total of

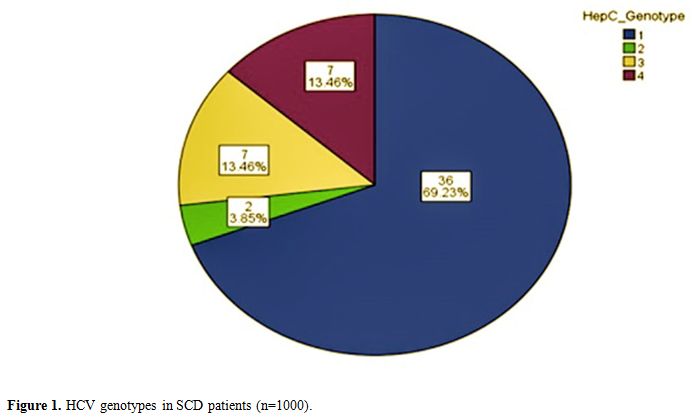

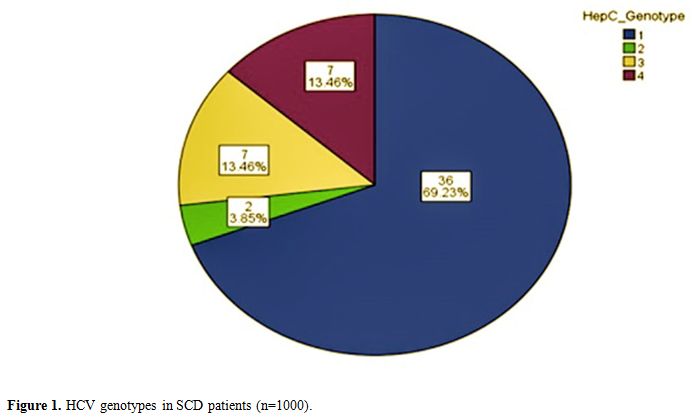

thirty-six patients 63.23%) had genotype 1; two patients (3.86%) had

genotype 2, seven patients (13.46) each had genotype 3, and 4 (Figure 1). Furthermore, none of the SCD patients in this cohort had positive serology for HIV.

|

Figure

1. HCV genotypes in SCD patients (n=1000). |

Abdominal

liver ultrasound showed a normal liver in 78.8% (788) patients, whereas

20.8% (208) had hepatomegaly and only four patients had liver cirrhosis

(0.4%). A total of thirty-six patients (3.6%) in this study cohort had

died; however, in only two patients, death was due to cirrhosis of

liver.

. Discussion

The

survival rate of SCD patients has recently increased with improved

patient care, including blood transfusions, vaccinations and use of

antibiotics. However, repeated blood transfusions are still necessary

for many patients with SCD. Thus, multiply transfused patients with SCD

are at an increased risk of transfusion-associated infections such as

HBV, HCV, and HIV.

The screening for HBsAg became available in the late 1960s and had been implemented widely since 1970s.[18]

Despite regular HBV screening and national neonatal vaccination

programs since early nineties, HBV infection is still present. In Oman,

the prevalence of HBV infection was 5.8% in healthy adult population.[15] In another study, Al Awaidy, S. et al.[19]

reported that the prevalence of HBV among pregnant Omani women in 2006

was found to be 7.1%, with 0.5% being HBeAg positive. However, there is

no data related to HBV in SCD population from Oman.

In our

study, we found that the prevalence of HBV infection among SCD was 2.3%

with 16 (1.6%) HBV DNA positive, and 0.1% HBeAg positive.

Significantly, the prevalence is considerably lower than the earlier

studies in the general Omani population[15,19].

A possible explanation for this lower prevalence is the higher

prevalence of anti-Hbs (74.4%) in our SCD patient cohort. This high

prevalence of anti-HBs positivity reflects the success of prophylactic

hepatitis B vaccinations that are judiciously pursued by our

physicians, as well as the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination in

this relatively young patient population. The isolated total anti-HBc

pattern (anti-HBs negative/anti-HBc positive) found in 8.7% in our

study may reflect previous hepatitis B exposure and ability of human

body to eliminate the virus in some cases after infection.

Although

the burden of chronic HBV viral infection was low (1.6%) in this study,

it reflects the potential for chronic liver disease and hepatocellular

carcinoma. Treatment of chronic HBV infection can control viral

replication in most patients and reduces the risks for progression and

may even reverse liver fibrosis. Nevertheless, in this study cohort,

liver cirrhosis was only documented in 0.4% of patients with 0.2%

deaths related to liver disease.

There has been a significant drop

in transfusion-associated viral hepatitis since the implementation of

testing for HCV in the early 1990s.[20] In 1993, Al Dhahry, S.H et al[21]

reported the prevalence of antibodies to HCV among Omani patients with

renal disease. They observed anti-HCV antibodies in 26.5% patients

undergoing hemodialysis, 13.4% kidney transplant patients and 1%

non-dialyzed non-transplanted patients with various renal diseases.[21] In another study, Al Dhahry, S.H et al.[22]

reported the prevalence of HCV among Omani blood donors between 1991 to

2001 using a third-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

and recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA) to confirm positive ELISA

tests.[22] Out of 30,012 samples from blood donors

that were screened for anti-HCV, 272 (0.91%) were positive. However,

among those, almost half (127) were confirmed positive by RIBA.[22] Al-Naamani, K et al,[23]

in a retrospective study of 200 thalassemic patients from Oman,

reported that the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in thalassemia

patients was 41%.[23] However, no previous data related to HCV in SCD population in Oman is available.

The

prevalence of anti-HCV positivity (12.6%) in this study was higher than

that observed in SCD patients from the United States (5.4%),[24] France (7.5%),[25] but lower than that reported from Egyptian SCD children (23%).[26]

Further, there is a 12-fold increase in the prevalence of HCV in SCD

patients in this study, as compared to that reported earlier by Al

Dahry et al.[22] from Oman, which was essentially a

population-based study. HCV is a major problem in SCD patients,

and this might be because we still do not have a specific HCV vaccine

as opposed to Hepatitis B vaccine. SCD patients are at great risk since

they are often multi-transfused, especially in those patients with a

severe disease background. The frequency of transfusion was identified

as a major risk factor for HCV infection, according to study conducted

in 1995 in Bahrain[27] and another in Siria reporting a cohort of frequently transfused hemoglobinopathy patients.[28]

However, although the risk of infection increased with increasing

frequency of transfusions, the prevalence of HCV in the current study

is much lower than reported in thalassemic patients from Oman (41%).[23]

Though there are several factors responsible for this high prevalence,

frequency of transfusions is indeed the most significant factor for the

high HCV prevalence in the thalassemia population from Oman.[23]

Further, although we did not study any close family contacts, lack of

transmission of HCV in very close family contacts of patients

undergoing multi-transfusions for thalassemia has been reported,

emphasizing that the nature of HCV transmission is predominantly by the

parenteral route.[29]

Further, the current study

found active HCV infection, confirmed by positive HCV RNA using RT-PCR,

in 5.2% of the anti-HCV positive patients. This datum reflects a

significant burden for chronic liver disease as these patients are at

risk of developing liver cirrhosis and progressing to end-stage liver

disease and liver cancer.[30] In 2016 the World

Health Organization (WHO) released their first global health sector

strategy with an ambitious plan to reduce the incidence of global

chronic hepatitis infections from the current 6–10 million cases of

chronic infection to 0.9 million cases worldwide, and to reduce the

annual deaths from chronic hepatitis from 1.4 million to less than 0.5

million by 2030.[31] It is now feasible to aim for

these objectives as the treatment for HCV has improved dramatically

with the addition of direct-acting antivirals, which are easy to take,

being an oral regimen that is highly effective, has minimal side

effects, and achieves cure rates of over 90%.[32,33]

This

study showed that HCV-genotype 1 was the most common genotype seen

(69.2%), which is similar to the most common HCV genotype reported in

thalassemic patients from Oman.[23] Although, the

genotype is not related to the mode of virus transmitted or with

histologic findings at presentation, patients with HCV genotype 1 tend

to develop more severe liver disease with lower rates of response to

interferon-based therapy than did patients with other HCV genotypes.[34]

HIV continues to be a major global public health issue. In 2016, an estimated 36.7 million people were living with HIV.[35] Some studies reported a low prevalence of HIV among SCD patients, with the prevalence in USA being 0.87%.[24]

In the current study, we did not identify any case with seropositivity

for HIV in this cohort, and no other cases have been identified with

SCD and HIV in our institution. Exposure to blood and blood products is

also common to two other diseases, i.e., hemophilia and thalassemia.

However, comparatively speaking, in our observation, although we had

seen respectively 3 and 4 HIV patients before 1990, currently,

among our 112 hemophilia and 200 thalassemia patients,[23]

we do not have any patient with positive serology for HIV-1 & 2.

The reason for the lower risk of HIV comorbidity with SCD is unclear.

Although the general population prevalence of HIV in Oman is low,[17]

SCD may have a unique effect in altering the risk of HIV infection or

progression, raising the possibility of SCD protective effect against

HIV infection.[36] Investigation of how the hemolytic

and immunological changes of SCD influence HIV might lead to a new

therapeutic or preventive approaches.[37]

Liver

involvement in patients with SCD includes a wide range of alterations,

from mild liver function test abnormalities to cirrhosis and acute

liver failure. Liver cirrhosis is a major public health problem and a

significant source of morbidity and mortality that is preventable and

underestimated. In HBV infection, it is estimated that 10% to 33% of

those who develop persistent infection end up with chronic hepatitis of

which 20% to 50% may develop liver cirrhosis,[38]

Studies in patients who had acquired hepatitis C by blood transfusion

for 15–25 years, revealed that 20% to 30% developed cirrhosis.[39]

In our current study we found that the proportion of liver cirrhosis

among HCV, HBV infected SCD patients was significantly low (0.4%), and

only two patients (0.2%) died due to liver cirrhosis.

SCD and homozygous β-thalassemia are common hemoglobinopathies in Oman,[5]

with financial consequences for national healthcare services. It is

thus prudent to follow the recommendations for blood banks and

transfusion services in Oman. The transfusions of such patients take

place in many hospitals throughout the country. Indications for blood

transfusions require local recommendations and guidelines to ensure

standardized levels of care.[40] Furthermore, not all

patients with positive results received blood transfusions. This

apparent discrepancy is mainly due to the fact that these patients also

receive blood transfusions at other health care facilities in the

Sultanate.

Conclusions

The

study documents the prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV infections among

SCD patients from Oman for the first time. Compared to the not affected

Omani population, the prevalence of HBV was significantly low

(anti-HBs), but that of HCV infection was significantly high

(anti-HCV). Persistence of viral infections was found to be 5.2% and

1.6% based on HCV PCR and HBV DNA respectively, indicating an ongoing

risk for chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and liver cancer.

Importantly, no case with HIV was observed. Although the overall

mortality was 3.6%, liver cirrhosis was seen in only 0.2% of cases.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the hospital administration for the use of hospital material in this study.

References

- Rees, D.C., Williams, T.N. & Gladwin, M.T., Sickle-cell disease. The Lancet, 2010 376(9757), pp.2018–2031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X.

- Bunn HF. Pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1997 Sep 11;337(11):762-9 http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199709113371107

- Steinberg MH. Genetic etiologies for phenotypic diversity in sickle cell anemia. Scientific World Journal. 2009; 9:46-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2009.10

- Al-Riyami,

A.A. Suleiman AJ, Afifi M, Al-Lamki ZM, Daar S., A community-based

study of common hereditary blood disorders in Oman. East Mediterr

Health J. 2001;7:1004-11. PMID: 15332742

- Al-Riyami,

A. & Ebrahim, G.J., Genetic Blood Disorders Survey in the Sultanate

of Oman. J Trop Pediatr. 2003 ;49 Suppl 1:i1-20. PMID: 12934793

- Alkindi

S, Al Zadjali S, Al Madhani A, et al Forecasting Hemoglobinopathy

Burden Through Neonatal Screening in Omani Neonates, Hemoglobin. 2010;

34, 135-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/03630261003677213

- Shilpa

Jain, Nitya Bakshi, Lakshmanan Krishnamurti, Acute Chest Syndrome in

Children with Sickle Cell Disease Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol.

2017; 30: 191–201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ped.2017.0814

- Vichinsky

EP, Neumayr LD, Earles AN, et al. Causes and outcomes of the acute

chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. National Acute Chest Syndrome

Study Group. N Eng. J Med ,2000; 342: 1855-1865. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200006223422502

- Josephson

CD, Su LL, Hillyer KL, Hillyer CD. Transfusion in the patient with

sickle cell disease: a critical review of the literature and

transfusion guidelines. Transfus Med Rev. 2007 Apr;21(2):118-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.11.003

- Lavanchy D. Chronic viral hepatitis as a public health issue in the world. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:991-1008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2008.11.002

- Margaret

E. Hellard, Roger Chou, and Philippa Easterbrook. WHO guidelines on

testing for hepatitis B and C – meeting targets for testing. BMC Infect

Dis. 2017; 17(Suppl 1): 703. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2765-2

- Poonam

Khetrapal Singh. Towards ending viral hepatitis as a public health

threat: translating new momentum into concrete results in South-East

Asia, Gut Pathog. 2018; 10: 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13099-018-0237-x

- Calderon,

G.M. González-Velázquez F, González-Bonilla CR, et al. Prevalence and

risk factors of hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, and human

immunodeficiency virus in multiply transfused recipients in Mexico.

Transfusion. 2009;49:2200-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02248.x

- Ocak,

S. Kaya H, Cetin M, Gali E, Ozturk M. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and

Hepatitis C in Patients with Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Anemia in a

Long-term Follow-up, Arch Med Res. 2006 ;37:895-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.04.007

- Al

Baqlani, S.A. Sy BT, Ratsch BA, et al. Molecular Epidemiology and

Genotyping of Hepatitis B Virus of HBsAg-Positive Patients in Oman,

PLoS One. 2014;9: e97759. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097759

- Mohamoud,

Y.A., Riome, S. & Abu-raddad, L.J., Epidemiology of hepatitis C

virus in the Arabian Gulf countries: Systematic review and

meta-analysis of prevalence. Int J Infect Dis. 2016; 46:116-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.012

- Ali

Elgalib, Samir Shah, Zeyana Al-Habsi, et al, HIV viral suppression in

Oman: Encouraging progress toward achieving the United Nations ‘third

90’, Int. J. Inf. Dis. 2018:71,94–99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.04.795

- Tawk,

H.M. Vickery K, Bisset L, Lo SK, Cossart YE; Infection in Endoscopy

Study Group. The significance of transfusion in the past as a risk for

current hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection: a study in endoscopy

patients. Transfusion. 2005 ;45:807-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04317.x

- Al

Awaidy, S. Abu-Elyazeed R, Al Hosani H, et al. Sero-epidemiology of

hepatitis B infection in pregnant women in Oman, Qatar and the United

Arab Emirates. J Infect. 2006 ;52:202-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04317.x

- Donahue,

J.G. Muñoz A, Ness PM, et al. The declining risk of post-transfusion

hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992 ;327:369-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199208063270601

- Al-Dhahry

SH, Aghanashinikar PN, al-Hasani MK, Buhl MR, Daar AS. Prevalence of

Antibodies to Hepatitis C Virus among Omani Patients with Renal

Disease., Infection. 1993 ;21:164-7. PMID: 7690010

- Al

Dhahry, S.H., Nograles JC, Rajapakse SM, Al Toqi FS, Kaminski GZ.

Laboratory diagnosis of viral hepatitis C: The Sultan Qaboos University

Hospital experience. J Sci Res Med Sci. 2003 ;5:15-20. PMID: 24019730

PMCID: PMC3174725

- Al-Naamani,

K. Al-Zakwani I, Al-Sinani S, Wasim F, Daar S. Prevalence of Hepatitis

C among Multi-transfused Thalassaemic Patients in Oman: Single centre

experience., Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015 ;15:e46-51. PMID: 25685385

PMCID: PMC4318606

- Master,

S. Patan S, Cingam S & Mansour RP. Prevalence of Chronic Hepatitis

B, Hepatitis C and HIV in Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease.

Blood, 2016,128 (22), p.4863 (ASH abstracts)

- Arlet

JB, Comarmond C, Habibi A, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of

Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adult Sickle Cell Disease Patients

Living in France, J Infect Dis Epidemiol 2016, 2:020. (Open Access)

- Mousa,

S.M. El-Ghamrawy MK, Gouda H, Khorshied M, El-Salam Ahmed DA, Shiba H.

Prevalence of Hepatitis C among Egyptian Children with Sickle Cell

Disease and the Role of IL28b Gene Polymorphisms in Spontaneous Viral

Clearance. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016 ;8:e2016007. http://dx.doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2016.007

- al-Mahroos,

F.T. & Ebrahim, A., Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and

human immune deficiency virus markers among patients with hereditary

haemolytic anaemias. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995;15:121-8. PMID: 7677412

- Yazaji,

W., Habbal, W., & Monem, F. (2016). Seropositivity of hepatitis b

and c among syrian multitransfused patients with hemoglobinopathy.

Mediterr J Hematol and Infect Dis, 8, e2016046. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2016.046

- Rosenthal

E, Hazani A, Segal D, Koren A, Kamal S, Rimon N, Atias D, Ben-Porath E.

Lack of transmission of hepatitis C virus in very close family contacts

of patients undergoing multitransfusions for thalassemia. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999 Jul;29(1):101-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005176-199907000-00025

- Alter

HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus

infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis.

2000;20:17–35. PMID: 10895429

- Organization WH. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021. http://www.who.int/health-accounts/platform_approach/en/. 2016.

- Ara

AK, Paul JP. New Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapies for Treatment of

Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y).

2015;11:458–66. PMID: 27118941 PMCID: PMC4843024

- Schietroma

I, Scheri GC, Pinacchio C, Statzu M, Petruzziello A, Vullo V. Hepatitis

C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and

Impact of Direct-Acting Antivirals. Open Virol J. 2018; 12:16–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874357901812010016

- Zein,

N.N. Rakela J, Krawitt EL, Reddy KR, Tominaga T, Persing DH. Hepatitis

C virus genotypes in the United States: epidemiology, pathogenicity,

and response to interferon therapy. Collaborative Study Group. Ann

Intern Med. 1996 ;125:634-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00002

- UNAIDS. Global AIDS update, 2016. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf

- Obaro S. Does sickle cell disease protect against HIV/AIDS? Sex Transm Infect. 2012 Nov;88:533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2012-050613

- Nouraie,

M., Nekhai, S. & Gordeuk, V.R., Sickle cell disease is associated

with decreased HIV but higher HBV and HCV comorbidities in U.S.

hospital discharge records: a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Infect.

2012 ;88:528-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2011-050459

- Claus

Niederau, Chronic hepatitis B in 2014: Great therapeutic progress,

large diagnostic deficit, World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 7; 20:

11595–11617. http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11595.

- Alberti, A., Chemello, L. & Benvegnu, L., Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:17-24. PMID: 10622555

- Arwa

Z. Al-Riyami and Shahina Daar, Transfusion in Haemoglobinopathies,

Review and recommendations for local blood banks and transfusion

services in Oman, Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018 Feb; 18(1): e3–e12. http://dx.doi.org/10.18295/squmj.2018.18.01.002