Yumeng Zhang1, Jinming Song2, David Rutenberg1 and Lubomir Sokol2.

1 University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33612

2 Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL 33612

Corresponding

author: Dr. Lubomir Sokol. Department of Malignant Hematology, Moffitt

Cancer Center, 12902 USF Magnolia Dr, Tampa FL 33612. E-mail:

Lubomir.Sokol@moffitt.org

Published: January 1, 2020

Received: August 14, 2019

Accepted: December 16, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020007 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.007

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

We

describe a case of impending acute liver failure in a patient with

Sézary syndrome (SS). The three-phase computed tomography (CT) of the

liver showed neither mass nor hepatomegaly. Liver biopsy confirmed

infiltration with malignant CD4+ clonal T-cells. Prompt administration

of combination chemotherapy, consisting of gemcitabine, dexamethasone,

and cisplatin (GDP), resulted in full recovery of liver function. To

the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of liver failure

from SS. Commercial next-generation sequencing panel identified 11

clinically relevant mutations. Interestingly, the identified ARID2

mutation, frequently observed in hepatocellular carcinoma, rarely

occurs in hematologic malignancies. Further studies are necessary to

elucidate the role of ARID2 mutations in the biological behavior of

Sezary cells, such as a propensity to infiltrate liver parenchyma.

|

Introduction

Cutaneous

T cell lymphoma (CTCL) is characterized by skin infiltration with

malignant monoclonal CD4+ T cells, or rarely CD8+ T cells. CTCL is rare

and mostly affects older patients with a median age of 60 years at

diagnosis. Early-stage mycosis fungoides (MF), manifesting with

patch/plague disease, has an indolent clinical course in contrast to

patients with skin tumors or leukemic disease. Sézary syndrome (SS) is

an aggressive leukemic form of CTCL. It presents with circulating

Sézary cells in peripheral blood, generalized erythroderma, and

frequently lymphadenopathy.[1]

Patients with

hematologic malignancies infrequently develop acute liver failure

(ALF). The main mechanisms for ALF include tumor infiltration,

drug-induced hepatotoxicity, and reactivation of viral hepatitis. ALF

has not been reported in SS. Here, we report a case of impending ALF

secondary to hepatic involvement of SS. The patient had full recovery

of the liver function after initiation of chemotherapy.

Case Presentation

A

70-year-old white man with MF on external beam radiation therapy

presented with uncontrolled pruritus, erythroderma, skin desquamation,

and rapidly enlarging lymphadenopathy of the neck, axilla, and groin

for three weeks. He also had fatigue and a 15 lb weight loss over one

month. Forty years ago, he was diagnosed with diffuse large B cell

lymphoma (DLBCL) of the right testis. The patient was successfully

treated with three cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin,

vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP), followed by methotrexate, radiation

therapy, and orchiectomy. He has not had recurrent disease since. Labs

on admission showed a white blood cell count of 20x103/µL (normal range [NR] 4.6-10.2x103/µL)

with 39% atypical lymphocytes. Liver function tests (LFT) showed an AST

of 159 IU/L (NR 10-50 IU/L), ALT of 263 IU/L (NR 0-41 IU/L), and

alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 326 IU/L (NR 40-130 IU/L). Total

bilirubin and INR were normal. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed

26234 Sézary cells/µL. Skin biopsy revealed a large cell transformation

of MF. Bone marrow biopsy showed mildly hypercellular marrow

infiltrated with a monoclonal CD4+ T cell population. Left axillary

lymph node biopsy showed an aberrant CD4+ T-cell population without

large-cell transformation. A high Ki-67 proliferation index (50%)

suggested an aggressive disease.

While being treated for his

symptoms, he developed worsening of transaminitis and anasarca on

hospital day (HD) 4. Despite stopping potentially hepatotoxic agents

including allopurinol and gabapentin, his LFTs rose exponentially. On

HD 6, his AST/ALT/ALP were 1570/1442/660 IU/L, respectively, total

bilirubin was 6.7 mg/dL, and INR was 1.3. Work-up included negative

infectious etiologies (hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C,

cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and

herpes simplex virus); negative hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

markers; negative antinuclear antibody and anti-mitochondria antibody.

Anti-smooth muscle antibody was mildly elevated (38 units, normal range

0-19 units), which was more consistent with liver injury than

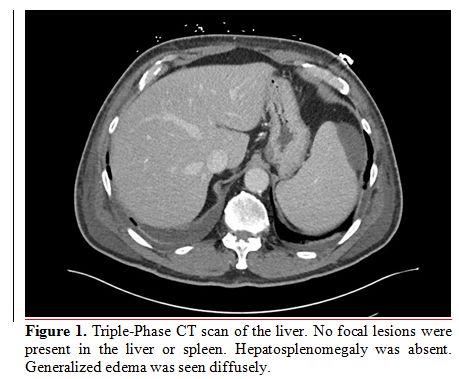

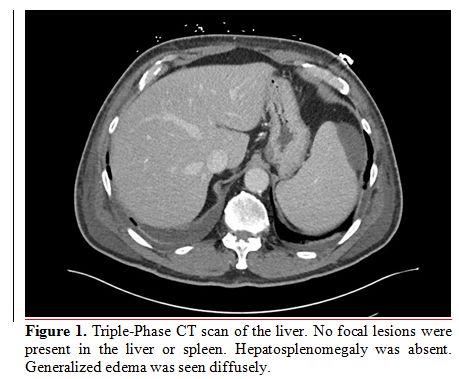

autoimmune hepatitis. Abdominal Doppler ultrasound and triple-phase CT

scan of the liver were negative for liver pathology or hepatomegaly (Figure 1).

|

Figure

1. Triple-Phase CT scan of the liver. No focal lesions were present in

the liver or spleen. Hepatosplenomegaly was absent. Generalized edema

was seen diffusely. |

A

trial of steroids was initiated. However, the AST/ALT continued to

increase rapidly to the 2000s IU/ml by HD 7. His jaundice and mental

status worsened. Despite the absence of liver abnormalities on imaging

studies, ALF secondary to hepatic involvement of SS was suspected. He

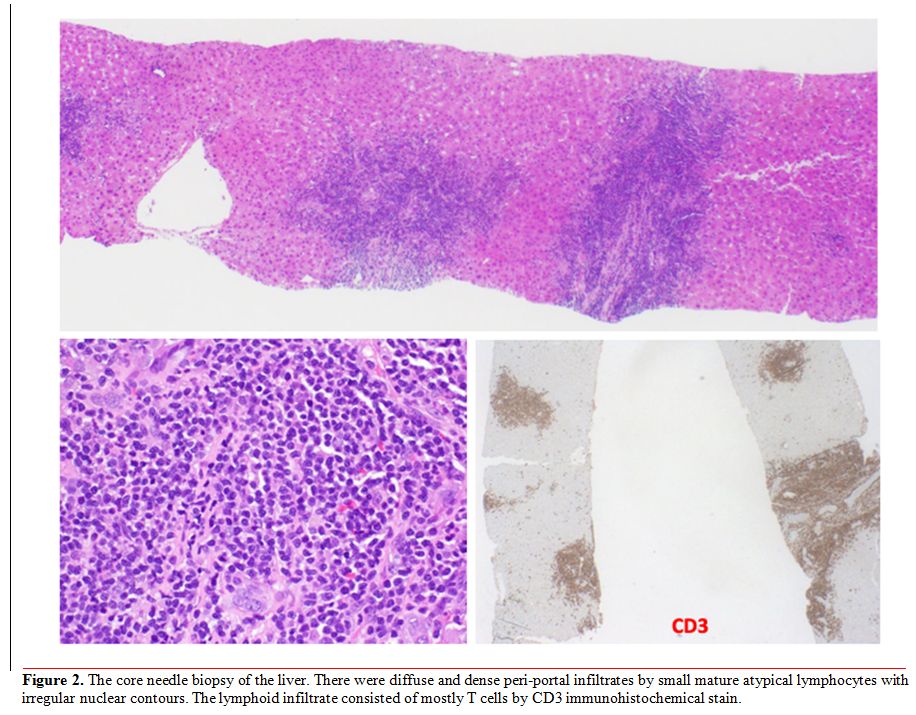

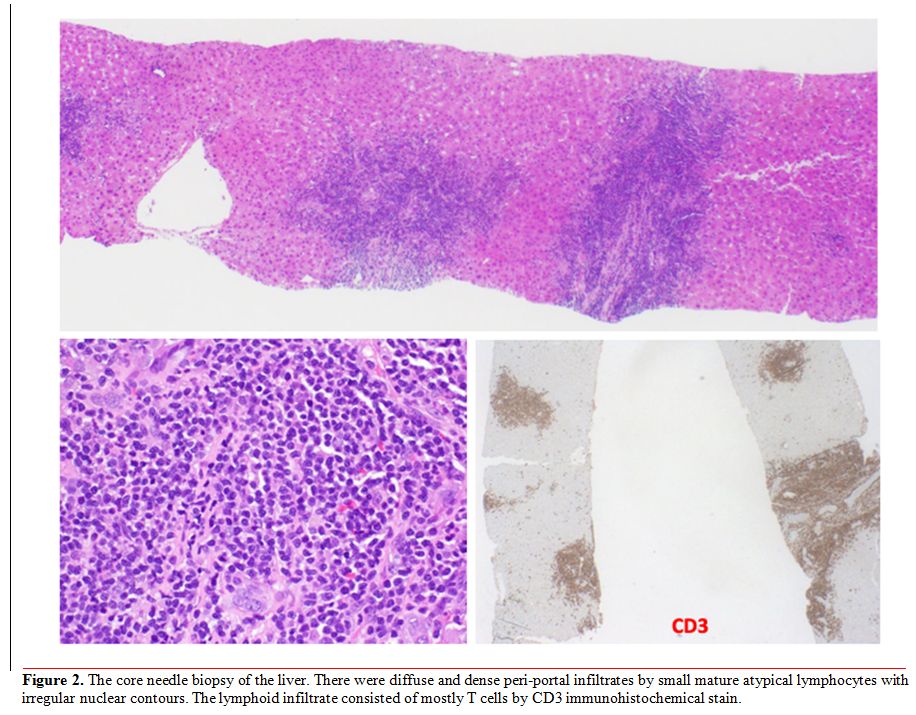

was referred for diagnostic core needle liver biopsy. The final

pathology report of the liver biopsy confirmed malignant hepatic

infiltration with Sézary cells. Cytomorphology showed dense portal

infiltrate by mostly small mature atypical lymphocytes without large

cell transformation; immunohistochemical staining revealed CD4+ T cells

with loss of CD7 (Figure 2);

flow cytometry and T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies of the

tissue confirmed monoclonal T cell population. Next-Generation

Sequencing (NGS) of peripheral blood (Foundation One Inc. Cambridge,

MA) showed a high mutation burden (25 mutations/Mb) and identified 31

genetic alternations. Seven clinically relevant mutations included

CCND3 P203L, STAT3 D661Y, ARID2 G70Fs*20, ASXL1 T822fs*11, CBL C3965,

CD58 Q32*, CDKN2a splice site 151-1G>A, CIITA Q909*, EP300 Q641*,

MAPK1 E322K, and TNFAIP3 loss.

|

Figure 2. The core needle

biopsy of the liver. There were diffuse and dense peri-portal

infiltrates by small mature atypical lymphocytes with irregular nuclear

contours. The lymphoid infiltrate consisted of mostly T cells by CD3

immunohistochemical stain. |

He

was treated with a chemotherapy regimen consisting of gemcitabine,

dexamethasone, and cisplatin (GDP). The patient’s LFTs and mental

status started to improve on the second day of GDP.

His LFTs

normalized and erythroderma resolved during the 1-month follow-up. He

completed two additional cycles of GDP, followed by maintenance

gemcitabine. Restaging PET/CT showed complete remission. Unfortunately,

he passed away six months later due to myocardial infarction.

Discussion

SS

comprises approximately 5% of all CTCL cases. SS carries a poor

prognosis with a median overall survival rate of 2-3 years. SS can

involve the bone marrow, liver, lung, and gastrointestinal tract in

advanced stages.[2] Large cell transformation in

patients with MF/SS is associated with more aggressive clinical

behavior. Huberman et al. reported visceral involvement in 70-90% CTCL

patients at the time of death.[3] In a small cohort,

16% of patients with CTCL had biopsy documented hepatic infiltrates.

Clinical factors that are associated with hepatic infiltrate include

peripheral blood involvement, leukocytosis, and generalized

erythroderma. Interestingly, none of the patients had abnormal LFTs.[3]

ALF is a very poor prognostic sign with a mortality rate of 83% and a

mean survival rate of 10.7 days from the time of diagnosis in other

non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Remission from chemotherapy only occurs in

less than 15% of cases.[4] In the case of acute liver

failure in a Japanese patient with MF, the patient passed away within

eight weeks of visceral involvement.[5]

To the

best of our knowledge, the present case is the first report of liver

injury from malignant hepatic infiltration of SS. This case showed that

the prompt administration of chemotherapy could result in the complete

recovery of liver function and prevent progression into ALF. The

diagnostic dilemma included the lack of abnormalities in multiple

imaging modalities and concerns for recurrent disease of the previously

treated DLBCL. Homogeneous infiltration of malignant cells in the liver

occasionally makes it difficult to detect with imaging studies and can

result in a delay in diagnosis. High clinical suspicion should trigger

liver biopsy and molecular studies.

A high mutation burden in

NGS may potentially explain the aggressiveness of the disease. Among

the identified mutations, TNFAIP3 mutations have been reported in CTCL

previously.[6] CCND3, STAT3, ASXL1, CBL, CDKN2A,

EP300, and MAPK1 have been reported in adult T cell lymphoma/leukemia

and other types of mature T cell lymphomas (COSMIC 2017).

ARID2

mutation has rarely been reported in hematologic malignancy

(prevalence: 0.5%), but frequently described in hepatocellular

carcinoma (prevalence: 5-20%).[5,7] ARID2 encodes a subunit of the SWI/SNF-B (PBAF) chromatin remodeling complex, which assists in mediating gene expression[8] and double-strand DNA gene repair.[9]

ARID2 functions as a tumor suppressor gene and is associated with

loss-of-function mutations in most cases. In the absence of ARID2,

cells are sensitized to DNA damage secondary to ultraviolet light and

other carcinogens. In the present case, ARID2 mutation was a frameshift

mutation of G70fs*20 in the splice site, likely resulting in loss of

function. The ARID2 mutation possibly predisposes Sezary cells to

acquire more mutations and aggressive features. Further studies are

necessary to elucidate the role of ARID2 mutations in the biological

behavior of Sezary cells, such as a propensity to infiltrate liver

parenchyma.

References

- Wilcox, R.A., Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017

update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol,

2017. 92(10): p. 1085-1102. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24876 PMid:28872191

- Scarisbrick,

J.J., et al., Prognostic factors, prognostic indices and staging in

mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: where are we now? Br J Dermatol,

2014. 170(6): p. 1226-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12909 PMid:24641480

- Huberman,

M.S., et al., Hepatic involvement in the cutaneous T-cell lymphomas:

results of percutaneous biopsy and peritoneoscopy. Cancer, 1980. 45(7):

p. 1683-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19800401)45:7<1683::AID-CNCR2820450727>3.0.CO;2-C

- Lettieri,

C.J. and B.W. Berg, Clinical features of non-Hodgkins lymphoma

presenting with acute liver failure: a report of five cases and review

of published experience. Am J Gastroenterol, 2003. 98(7): p. 1641-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07536.x PMid:12873593

- Shibata,

S., et al., Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides with severe hepatic

failure due to hepatic involvement. Acta Derm Venereol, 2009. 89(4): p.

423-4. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-0665 PMid:19688164

- Braun,

F.C., et al., Tumor suppressor TNFAIP3 (A20) is frequently deleted in

Sezary syndrome. Leukemia, 2011. 25(9): p. 1494-501. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.101 PMid:21625233

- Zhao, H., et al., ARID2: a new tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget, 2011. 2(11): p. 886-91. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.355 PMid:22095441 PMCid:PMC3259997

- Lemon,

B., et al., Selectivity of chromatin-remodelling cofactors for

ligand-activated transcription. Nature, 2001. 414(6866): p. 924-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/414924a PMid:11780067

- Kakarougkas,

A., et al., Requirement for PBAF in transcriptional repression and

repair at DNA breaks in actively transcribed regions of chromatin. Mol

Cell, 2014. 55(5): p. 723-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.028 PMid:25066234 PMCid:PMC4157577

[TOP]